Abstract

CONTEXT:

Loss of cervical lordosis is associated with decreased vertebral artery hemodynamics.

AIM:

The aim of this study is to evaluate cerebral blood flow changes on brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) in patients with loss of cervical lordosis before and following correction of cervical lordosis.

SETTINGS AND DESIGN:

This study is a retrospective consecutive case series of patients in a private practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Cervical lordosis of seven patients (five females and two males, 28–58 years) was measured on lateral cervical radiographs ranging from −13.1° to 19.0° (ideal is −42.0°). Brain MRAs were analyzed for pixel intensities representing blood flow. Pixel intensity of the cerebral vasculature was quantified, and percentage change was determined.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED:

A Student's t-test established significance of the percentage change in cerebral blood flow between pre- and postcervical lordosis adjustment images. Regression analysis was performed. An a priori analysis determined correlation between cervical lordosis and change in MRA pixel intensity. The statistician was blinded to the cervical lordosis.

RESULTS:

Pixel intensity increased 23.0%–225.9%, and a Student's t-test determined that the increase was significant (P < 0.001). Regression analysis of the change in pixel intensity versus the cervical lordosis showed that as the deviation from a normal cervical lordosis increases, percentage change in pixel intensity on MRA decreases.

CONCLUSION:

These results indicate that correction of cervical lordosis may be associated with an immediate increase in cerebral blood flow. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and understand clinical implications.

Keywords: Brain magnetic resonance angiogram, cerebral artery, cerebral blood flow, Cervical Denneroll™, cervical lordosis

Introduction

Loss of lordosis of the cervical spine is associated with decreased vertebral artery hemodynamics.[1] “Vertebral arteries proceed superiorly, in the transverse foramen of each cervical vertebra and merge to form the single midline basilar artery”[1] which continues to the circle of Willis and cerebral arteries. Based on this close anatomical relationship between the cervical spine, the vertebral arteries, and cerebral vasculature, we hypothesized that improvement in cervical hypolordosis increases collateral cerebral artery hemodynamics and circulation. This retrospective consecutive case series evaluates brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) in patients with cervical hypolordosis before and following correction of cervical lordosis.

Materials and Methods

All procedures performed in this case series involving the seven human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the case series. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article. The participants were patients in a private chiropractic practice, clinically evaluated by a doctor of chiropractic with 18 years of experience, and provided informed consent for publication of the results of this case.

The seven patients were made up of five females and two males with an age range of 28–58 years and a mean age of 42 years. Cervical lordosis was measured on neutral lateral cervical radiographs using PostureRay®X-ray analysis electronic medical record (EMR) software (PostureCo, Inc., Trinity, FL, USA) according to the Harrison posterior tangent method.[2] The posterior tangent method has established high intraclass and interclass reliabilities with a “smaller standard error of measurement than the four-line Cobb methods.”[3] Cervical lordosis is defined as the angle between the lines tangent to the posterior aspect of C2 and C7 vertebral bodies.[2] Inclusion criteria were cervical lordosis <−25° as this is one standard deviation below the mean value reported by Harrison et al.[4,5] Research has shown that the range of normal cervical lordosis, measured at the posterior of C2 and C7 vertebrae, is from − 16.5° to −66.0°, with a mean of −34°[6] and an ideal normal of −42°.[7] The negative sign indicates the normal direction of curvature for cervical lordosis. A positive angle indicates a cervical kyphosis or reversal of cervical curve. In this study, precervical lordosis adjustment measurements ranged from 19.0 to − 20.4° with a mean of −1.8° [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Postcervical lordosis adjustment measurements ranged from −22.1° to −44.7° with a mean of −37.3° [Table 1 and Figure 2]. Exclusion criteria were presence of hypoplastic vertebral artery, unresolved head trauma, psychiatric disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety), age younger than 18 or older than 60 years, cervical spondylosis, cervical rib, block vertebra, cardiovascular disorders (i.e., valvular heart disease), acute or chronic infections, rheumatic diseases, or any other systemic disorders.[1]

Table 1.

Cervical lordosis and cerebral blood flow quantifications of participants for pre- and postcervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram

| Participants | Normal ARA C2-C7 (°) | Precervical ARA C2-C7 adjustment (°) | Deviation from ideal ARA C2-C7 (°) | Postcervical ARA C2-C7 adjustment (°) | Difference between from pre to post-ARA C2-C7 (°) | Preadjustment MRA area over threshold (in2) | Postadjustment MRA area over threshold (in2) | Preadjustment MRA total pixel intensity | Postadjustment MRA total pixel intensity | Percentage change in total pixel intensity (%) | Preadjustment MRA threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −42.0 | 19.0 | 61 | −34.7 | 53.7 | 0.444 | 0.525 | 453,094 | 557,461 | 23.0 | 76 |

| 2 | −42.0 | 6.7 | 48.7 | −42.2 | 48.9 | 0.257 | 0.311 | 190,537 | 240,016 | 26.0 | 60 |

| 3 | −42.0 | 3.7 | 45.7 | −39.8 | 43.5 | 0.104 | 0.273 | 84,668 | 249,567 | 194.8 | 70 |

| 4 | −42.0 | 3.0 | 45 | −44.4 | 47.4 | 0.304 | 0.427 | 300,480 | 444,834 | 48.0 | 79 |

| 5 | −42.0 | −11.8 | 30.2 | −22.1 | 10.3 | 0.190 | 0.256 | 170,810 | 256,071 | 49.9 | 70 |

| 6 | −42.0 | −13.1 | 28.9 | −44.7 | 31.6 | 0.333 | 0.655 | 386,883 | 841,061 | 117.4 | 90 |

| 7 | −42.0 | −20.4 | 21.6 | −33.1 | 13.1 | 0.235 | 0.607 | 176,260 | 574,491 | 225.9 | 65 |

| Mean | −42.0 | −1.8 | 40.2 | −37.3 | 35.5 | 1.721 | 2.815 | 251,819 | 451,929 | 97.9 | 73 |

ARA C2-C7: Absolute rotational angle or cervical lordosis from C2 to C7 vertebrae, MRA: Magnetic resonance angiogram

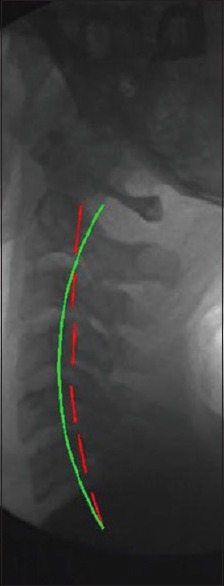

Figure 1.

Precervical lordosis adjustment radiograph. Lateral cervical images were analyzed using PostureRay® EMR software. Preradiographs show patients without the Cervical Denneroll™ Spinal Orthotic. Each image was analyzed for cervical lordosis measurements using the Harrison posterior tangent method. Red indicates the posterior aspect of the cervical vertebrae from C2 to C7. Green indicates ideal cervical lordosis from C2 to C7

Figure 2.

Postcervical lordosis adjustment radiograph. Lateral cervical images were analyzed using PostureRay® EMR software. Postradiographs show the patients with the Cervical Denneroll™ Spinal Orthotic applied as a fulcrum to the cervical spine yielding an increase in cervical lordosis. Each image was analyzed for cervical lordosis measurements using the Harrison posterior tangent method. Red indicates the posterior aspect of the cervical vertebrae from C2 to C7. Green indicates ideal cervical lordosis from C2 to C7

Brain MRA was obtained before and following cervical lordosis adjustment which was made using the Cervical Denneroll™ Spinal Orthotic (Denneroll Pty Ltd, New South Wales, Australia). As such, the findings from the MRAs before the cervical spine adjustment were served as control data compared to the findings of the MRAs following cervical lordosis adjustment. The MRAs were performed at a private medical imaging facility by a radiologic technologist certified by the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists with 8 years of experience. The Cervical Denneroll™ was used to correct loss of cervical lordosis via Mirror Image® cervical extension.[8] Precervical lordosis adjustment MRA was performed with the patient lying flat, supine, and with their arms at their sides. The timing of the intervention was controlled. The Cervical DennerollTM was applied to all patients immediately following the preadjustment MRA. The Cervical Denneroll™ was placed posterior to the middle-to-lower cervical spine providing a fulcrum and creating the desired cervical spine extension, and a postcervical lordosis adjustment MRA was performed with the patient lying flat, supine, and with their arms at their sides.

The circle of Willis and cerebral artery values were measured on brain MRA. Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined by the same area within each patient, and measurements taken therein were normalized internally. The ROI was the same per patient to measure pixel intensity pre- and postcervical lordosis adjustments. These measurements were then normalized internally, and the fold increase in blood flow to the area was reported. To compare images for each patient pre- and postcervical lordosis adjustments, pixel thresholds were determined for the image set and the pixel intensity above the threshold was measured. This method ensured that the background for the image set was constant. The fold change in pixel intensity was determined for each image set based on the two images. Each set was normalized internally so that only the fold change from the initial measurement would be compared to the initial measurement. Images were analyzed using FIJI/ImageJ.[9] Each image set was converted to an 8-bit TIF format, and appropriate pixel thresholds were set for each image pair using the threshold tool [Figures 3–6]. Pixel intensity of the cerebral vasculature was quantified by first selecting the ROI using the oval tool and quantifying the pixel intensity above the threshold using the analysis tool [Figures 4 and 6]. Pixel intensity is a gray scale depending on the degree of white or black in each pixel. Images were converted to an 8-bit format which has a gray scale from 0 (black) to 255 (white). The threshold for the images was set so that the brighter pixels, indicating blood flow, were compared. The program measured every pixel above the threshold (0–255) to give the total intensity based on the gray scale. The evaluation parameters included initial pixel intensity (Ii), final pixel intensity (If), and percentage change in pixel intensity (%ΔI). For each image set, the percentage change in pixel intensity was determined before and after cervical adjustment. %ΔI is the ratio of the difference between the Ifand the Iidivided by the Iiand multiplied by 100: %ΔI = (If– Ii)/Ii× 100 and provides information about cerebral blood flow (CBF). Pixel intensity analyses were done by the same PhD researcher who was blinded to the status of cervical lordosis and has 7 years of experience with the FIJI/ImageJ.

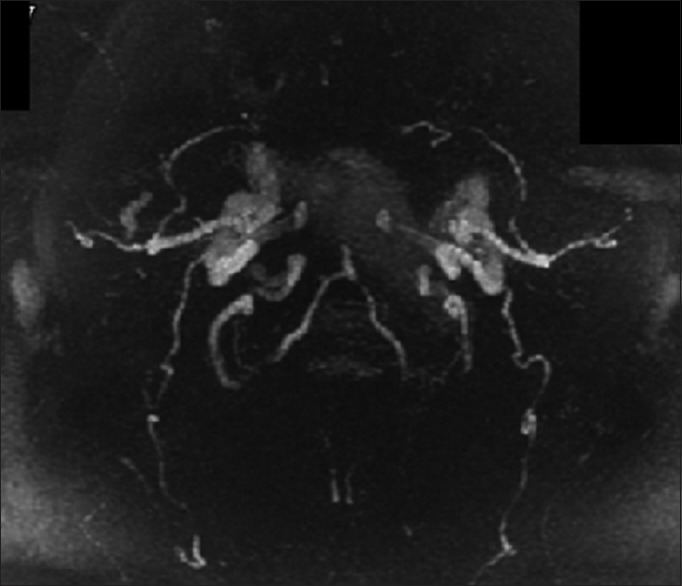

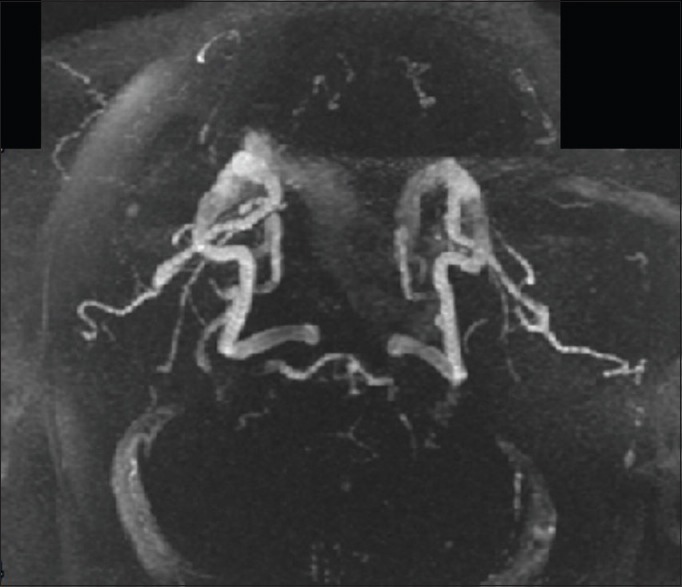

Figure 3.

Precervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram. Brain magnetic resonance angiogram images were analyzed using FIJI/ImageJ. Each image set was converted to an 8-bit TIF format and appropriate pixel thresholds were set for each image pair using the threshold tool. White indicates blood in cerebral vasculature

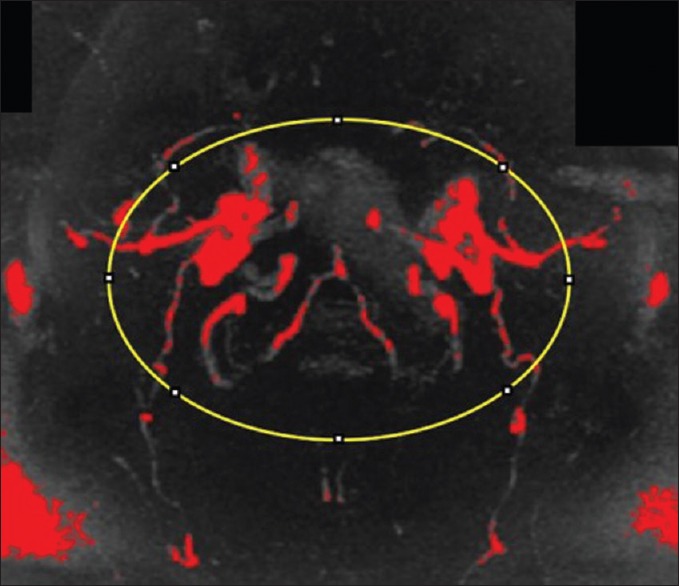

Figure 6.

Postcervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram pixel intensity analysis using FIJI/ImageJ. Pixel intensity of the cerebral vasculature was quantified by selecting the region of interest and quantifying pixel intensity. The threshold for the images was set so that the pixels indicating blood flow were compared. The increased quantity of red in the postcervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram indicates increased blood volume after correction of cervical lordosis. Red indicates pixels above threshold quantifying blood in cerebral vasculature. Yellow indicates the region of interest selected using the oval tool

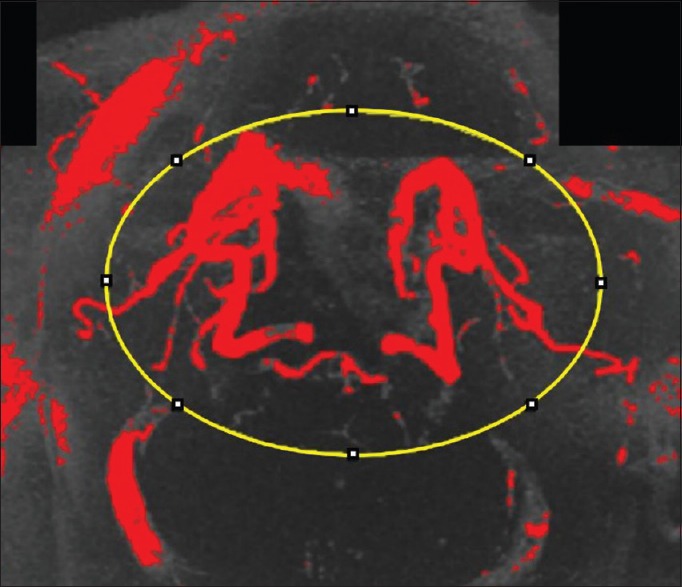

Figure 4.

Precervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram pixel intensity analysis using FIJI/ImageJ. Pixel intensity of the cerebral vasculature was quantified by selecting the region of interest and quantifying pixel intensity. The threshold for the images was set so that the pixels indicating blood flow were compared. The quantity of red in the precervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram serves as a baseline for this patient. Red indicates pixels above threshold quantifying blood in cerebral vasculature. Yellow indicates the region of interest selected using the oval tool

Figure 5.

Postcervical lordosis adjustment magnetic resonance angiogram. Brain magnetic resonance angiogram images were analyzed using FIJI/ImageJ. Each image set was converted to an 8-bit TIF format, and appropriate pixel thresholds were set for each image pair using the threshold tool. White indicates blood in cerebral vasculature

A Student's t-test was used to establish the significance of the percentage change in pixel intensity between the pre- and postadjustment image sets using the Data Analysis Plugin in Microsoft Excel. A regression analysis of the change in pixel intensity versus the cervical lordosis was performed. An a priori analysis was performed using G*Power 3 software to calculate the required sample size to produce a significant correlation between measured cervical lordosis and change in MRA pixel intensity. The statistician was blinded to the status of cervical lordosis.

Results

Still MRA images were analyzed using FIJI/ImageJ and their pixel intensities representing the fold change in measured blood flow were quantified [Table 1].[9] Pixel intensities for each image following the cervical adjustment were normalized to the image taken before the adjustment to calculate the percentage or fold change in pixel intensity. In each case, an increase in pixel intensity was observed ranging from 23.0% to 225.9%, and a Student's t-test showed that the observed increase was statistically significant within the population tested (P = 0.001) [Table 2]. These data indicate that correction of cervical lordosis may result in an immediate increase in the amount of CBF of the brain.

Table 2.

Student’s t-test of two sample means assuming unequal variances

| Parameter | Variable 1 | Variable 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1 | 1.9771 |

| Variance | 0 | 0.6919 |

| Observations | 7 | 7 |

| Parameter | Value | |

| Hypothesized MD | 0 | |

| df | 6 | |

| t statistic | −3.108 | |

| P (T < ) one-tail | 0.00104 | |

| t critical one-tail | 1.9432 | |

| P (T<t) two-tail | 0.02090 | |

| t critical two-tail | 2.4469 | |

MD: Mean difference

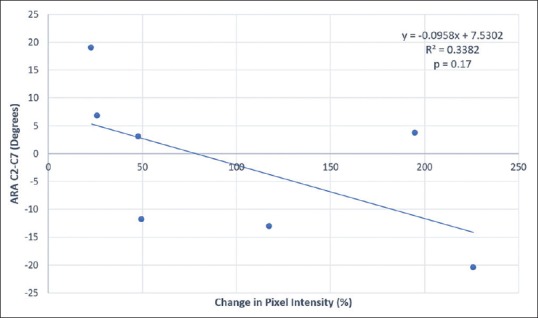

A regression analysis of the change in pixel intensity versus the cervical lordosis (absolute rotational angle [ARA] C2–C7) was performed [Table 3].[10] This analysis showed that as the deviation from a normal ARA increases, the percentage change in pixel intensity observed by MRA decreases [Table 3 and Figure 7]. The R-squared value for this interaction is 0.3382, indicating that 33.8% of the possible changes in observed pixel intensity can be attributed to the initial measured cervical lordosis [Table 3]. When there is a statistically significant correlation, a less than perfect linear regression is still notable.[11] A larger sample size may allow for increased statistical significance.

Table 3.

Regression analysis

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Multiple R | 0.581585445 |

| R2 | 0.33824163 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.205889956 |

| SE | 12.23919497 |

| Observations | 7 |

SE: Standard error

Figure 7.

Change in pixel intensity versus absolute rotational angle (cervical lordosis) from C2 to C7 vertebrae. This linear regression analysis shows that as a deviation from a normal ARA increases, the percentage change in pixel intensity observed by magnetic resonance angiogram decreases. The R-squared value for this interaction is 0.3382, indicating that 33.8% of the possible change in observed pixel intensity can be attributed to the initial measured cervical lordosis. ARA C2–C7 is the absolute rotational angle measurement of cervical lordosis from C2 to C7 vertebrae (normal is 34° and ideal is 42°)

An a priori analysis was performed using G*Power 3 software to calculate the required sample size to produce a significant correlation between measured ARA C2–C7 and change in MRA pixel intensity.[12] If the effect size and variance remain the same, a sample size of n = 16 would give an 80% chance of achieving P < 0.05 (r = 0.8 and P < 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

A priori analysis

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Input | |

| Tail (s) | 1 |

| Effect size r | 0.5813777 |

| α error probability | 0.05 |

| Power | 0.8 |

| Output | |

| Sample size | 16 |

| Actual power | 0.802301 |

Discussion

This retrospective consecutive case series was performed to test the hypothesis that loss of cervical lordosis may be associated with the circle of Willis and cerebral artery hemodynamics. The results of this case series revealed that the circle of Willis and cerebral artery parameters were significantly different between pre- and postcervical adjustments with preadjustment values showing lower values in comparison to postadjustment values. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published data investigating the effect of loss of cervical lordosis on cerebral artery parameters. Our findings demonstrate preliminary evidence that loss of cervical lordosis may play a role in the development of changes related to the circle of Willis and cerebral artery hemodynamics and decreased blood flow in the brain.

One strength of this case series is that the patients are consecutive which eliminates selection bias. One limitation of our study is that the sample size is small in total as well as within narrowed age ranges and sexes. Another limitation is that our results cannot be generalized to pediatric or geriatric populations as the participants' ages ranged from 28 to 58 years. Another limitation is that the cervical spinal orthotic changes the angle of the head and affects the angulation of the brain vasculature on the MRA.

A normal sagittal cervical spine has a lordotic curve.[6] Loss of lordosis or cervical kyphosis is associated with increased spinal cord and nerve root tension, pain, disability, and poor health and quality of life.[13,14] The poor health outcomes and disease processes related to loss of cervical curve originate from prolonged biomechanical stresses and strains in the neural elements.[6] Loss of cervical lordosis leads to very large altered stresses to the vertebrae providing the basis for vertebral compression, osteoarthritis, and osteophyte formation consistent with Wolff's law.[15] In addition to these skeletal changes in the cervical spine, the muscles and soft tissue that support the neck work harder to compensate for biomechanical instability creating soft-tissue weakness and damage.[16,17] As such, since the basilar artery is formed by the anterior spinal artery which courses through the spinal cord and the vertebral arteries which course cephalad through the transverse foramina of the first six vertebrae, prolonged aberrant stresses and strains applied to the spine will be applied to the vasculature within the spine.[18,19,20]

Clinical trials have shown that correction of cervical lordosis improves neuromusculoskeletal conditions such as cervical spondylotic radiculopathy, neck pain, segmental motion, lumbosacral radiculopathy, discogenic cervical radiculopathy, cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility, and central conduction time and neuroplasticity[8,21,22,23,24] and visceral conditions such as dizziness and cervicogenic headaches.[8] The spinal correction technique applied throughout these clinical trials employs imaging before care to determine the physiological effects of the technique protocol to ensure effective spinal care. Considering the research showing decreased cervical hemodynamics with loss of cervical lordosis and well-established spinal correction technique, MRA imaging was performed before and following cervical spine adjustments.

In this case series, data indicate that correction of cervical lordosis results in an immediate increase in the amount of CBF of the brain [Table 1] consistent with the notion that biomechanics influence physiology. Furthermore, the analysis shows that as the deviation from a normal cervical lordosis increases, the percentage change in pixel intensity observed by MRA decreases [Table 3 and Figure 7]. This may be due to the viscoelastic response of the vertebral arteries under prolonged stresses and strains due to a straightening or reversal of curve in the cervical spine. Arteries under prolonged stresses and strains become stiffer and less elastic.[25,26] As such, restoration of normal cervical lordosis may result in a slower response from arteries that were stressed and strained the most and a faster response from arteries that were stressed and strained the least.

Loss of cervical lordosis has been associated with decreased vertebral artery hemodynamics.[1] A relationship between loss of cervical lordosis and the vasculature that follows the vertebral arteries is an expected and logical finding. However, the possible effects of loss of cervical lordosis on cerebral hemodynamics and their clinical implications are completely unknown. Because the cerebral arteries are a major source of blood supply to the brain,[27] the possible factors affecting these vasculatures justify investigation.

The circle of Willis and cerebral artery hemodynamics have not been studied in patients with loss of cervical lordosis. However, patients with instability of the cervical spine of >3 mm of vertebral dislocation caused cerebral circulation dysfunction in 80% of cases,[28] showing an association of biomechanical stress and strain in the cervical spine with cerebral circulation. We restricted our sample to individuals aged 18–60 years of age, and we included the participants without instability of the cervical spine of >3 mm of vertebral dislocation to eliminate the effects on cerebral vasculature.

While the clinical impact of loss of cervical lordosis on various health measures is well-documented,[6,13,29] there are not many studies measuring the clinical impact of cervical lordosis on cerebral vasculature and addressing pathophysiologic mechanisms. Our results may be helpful in addressing pathophysiological mechanisms to help create a better understanding of potential clinical implications. “Substantial evidence suggests that the neurodegenerative process (for dementia and Alzheimer's disease [AD]) is initiated by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion.”[30]“Cervicogenic headache is a relatively common and still controversial form of headache arising from the structures in the neck.”[31]“A control group did not show any changes in CBF between two time points, but concussed athletes demonstrated a significant decrease in CBF at 8 days relative to within 24 h.”[32] In addition, CBF has been linked to sports-related concussion outcomes and recovery. As CBF increased in athletes following sports-related concussion, the magnitude of initial psychiatric symptoms decreased, “suggesting a potential prognostic indication for CBF as a biomarker.”[33]

The methods or results of this cases series are not being compared to studies cited in this paper. The studies cited show potential clinical significance and relevance in healthcare providing that future studies determine that correction of cervical lordosis is associated with increase in cerebral blood flow. Studying and identifying the relationship between vascular and extraspinal changes and cervical alignment may be important for considerations for spinal care. Further studies are needed to determine clinical implications of this, including rates and predisposition to transient ischemic attack or strokes. A study on how correction of cervical lordosis affects cerebral perfusion using perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging or a computed tomography perfusion scan would be warranted for dementia, AD, cervicogenic headaches, and traumatic brain injury.

The results of this case series show that correction of loss of cervical lordosis was associated with increased cerebral artery parameters indicating an immediate increase in blood flow in the brain. Evidence hierarchies reflect the relative value of different types of research, providing levels of evidence. There is neither study nor level of evidence which provides unequivocal statements. Studies are always confined to their inclusion criteria as well as time, location, environment, etc., Case studies and case series help to document remarkable or noteworthy findings and explain their relevance. This case series shows a significant increase in the cerebral vascular area indicating an increase in blood flow through the brain with improvement in cervical spinal curvature. This study follows another study which shows that decreased hemodynamics in the cervical region is associated with loss of cervical curvature. Various studies show how AD, dementia, headaches, and postconcussion and postmild traumatic brain injury symptoms are affected by CBF. This manuscript reports on remarkable and noteworthy findings that provide evidence supporting the need for further investigation. This study opens the door for future studies and clinical trials to confirm or deny these findings helping us to understand better human physiology and health which is of the utmost value. Further studies and clinical trials must include more participants and need to be done to confirm these findings and to understand their possible clinical implications. It would help to show MRA data of the patients before loss of cervical lordosis to compare with data following loss of cervical lordosis and correction thereof. However, loss of cervical lordosis can occur slowly, over years or decades due to poor posture and ergonomics, or more quickly with a trauma such as whiplash. One limitation with measuring CBF before loss of cervical lordosis and following loss of cervical lordosis due to poor posture and ergonomics over years or decades is that the data would compare a person to their much younger selves. There would be many variables to consider in comparing MRA data that were years apart such as vascular elasticity. A difficulty with measuring CBF before loss of cervical lordosis and following loss of cervical lordosis due to trauma such as whiplash is that we do not know when a whiplash-inducing trauma event may occur and the Institutional Review Board approval for inducing cervical trauma via whiplash is not feasible. Furthermore, it is unrealistic that patients who suffer from whiplash trauma would have MRA data just before the trauma. Further, the trauma has the potential to damage internal structures which add another variable. It would be valuable to compare a matched control group with a healthy cervical lordosis to one with loss in cervical lordosis (with long-term follow-up analyses), and this will be considered for future studies. In addition, to exclude the effect of the correction procedure itself, future studies need to include long-term follow-up analyses to determine whether improvement of CBF is conserved.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bulut MD, Alpayci M, Şenköy E, Bora A, Yazmalar L, Yavuz A, et al. Decreased vertebral artery hemodynamics in patients with loss of cervical lordosis. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:495–500. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson BL, Harrison DD, Robertson GA, Barker WF. Chiropractic biophysics lateral cervical film analysis reliability. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16:384–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Troyanovich SJ, Janik TJ, Holland B, et al. Cobb method or Harrison posterior tangent method: Which to choose for lateral cervical radiographic analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2072–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Holland B. Comparisons of lordotic cervical spine curvatures to a theoretical ideal model of the static sagittal cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:667–75. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Ferrantelli JR, Haas JW, et al. Modeling of the sagittal cervical spine as a method to discriminate hypolordosis: Results of elliptical and circular modeling in 72 asymptomatic subjects, 52 acute neck pain subjects, and 70 chronic neck pain subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:2485–92. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144449.90741.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison DD, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Murphy DJ. A normal sagittal spinal configuration: A desirable clinical outcome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:398–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Harrison DE, Colloca CJ. Evaluation of the assumptions used to derive an ideal normal cervical spine model. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:246–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moustafa IM, Diab AA, Harrison DE. The effect of normalizing the sagittal cervical configuration on dizziness, neck pain, and cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility: A 1-year randomized controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53:57–71. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KJ, Wiest MM, Carlin JB. Statistics for clinicians: An introduction to linear regression. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:940–3. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalmer BJ. Understanding Statistics. New York: M. Dekker; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, Harrison DE, Holland B. Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugar O. Adverse mechanical tension in the central nervous system: An analysis of cause and effect; relief by functional neurosurgery. JAMA. 1978;240:2776. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, William Jones E, Cailliet R, Normand M, et al. Comparison of axial and flexural stresses in lordosis and three buckled configurations of the cervical spine. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16:276–84. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpayci M, Şenköy E, Delen V, Şah V, Yazmalar L, Erden M, et al. Decreased neck muscle strength in patients with the loss of cervical Lordosis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2016;33:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon SY, Moon HI, Lee SC, Eun NL, Kim YW. Association between cervical lordotic curvature and cervical muscle cross-sectional area in patients with loss of cervical lordosis. Clin Anat. 2018;31:710–5. doi: 10.1002/ca.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchanan CC, McLaughlin N, Lu DC, Martin NA. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion secondary to adjacent-level degeneration following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:714–21. doi: 10.3171/2014.3.SPINE13452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming JB, Vora TK, Harrigan MR. Rare case of bilateral vertebral artery stenosis caused by C4-5 spondylotic changes manifesting with bilateral bow Hunter's syndrome. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:799.E1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaoka Y, Ichikawa Y, Morita A. Evaluation of rotational vertebral artery occlusion using ultrasound facilitates the detection of arterial dissection in the atlas loop. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:647–51. doi: 10.1111/jon.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moustafa IM, Diab AM, Ahmed A, Harrison DE. The efficacy of cervical lordosis rehabilitation for nerve root function, pain, and segmental motion in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy. Physiotherapy. 2011;97(Suppl 1):846–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moustafa IM, Diab AA, Harrison DE. The Efficacy of Cervical Lordosis Rehabilitation for Nerve Root Function, Pain, and Segmental Motion in Cervical Spondylotic Radiculopathy: A Randomized Control Trial. Proceedings of the 13th World Federation of Chiropractic Biennial Congress/ECU Convention; Athens, Greece: Mediterranean Region Award Winning Paper; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moustafa IM, Diab AA, Taha S, Harrison DE. Addition of a sagittal cervical posture corrective orthotic device to a multimodal rehabilitation program improves short- and long-term outcomes in patients with discogenic cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:2034–44. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moustafa IM, Diab AA, Hegazy FA, Harrison DE. Does rehabilitation of cervical lordosis influence sagittal cervical spine flexion extension kinematics in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy subjects? J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30:937–41. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergel DH. The static elastic properties of the arterial wall. J Physiol. 1961;156:445–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charalambous HP, Roussis PC, Giannakopoulos AE. The effect of strain hardening on the dynamic response of human artery segments. Open Biomed Eng J. 2017;11:85–110. doi: 10.2174/1874120701711010085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Katz LC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. The Blood Supply of the Brain and Spinal Cord. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grinenko EA, Kul'chikov AE, Musin RS, Morozov SG. The effect of the instability of cervical spine on the hemodynamics in the vertebrobasilar system. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2014;114:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheer JK, Tang JA, Smith JS, Acosta FL, Jr, Protopsaltis TS, Blondel B, et al. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: A review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:141–59. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Marco LY, Venneri A, Farkas E, Evans PC, Marzo A, Frangi AF, et al. Vascular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease – A review of endothelium-mediated mechanisms and ensuing vicious circles. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;82:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inan N, Ateş Y. Cervicogenic headache: Pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria and treatment. Agri. 2005;17:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Nelson LD, LaRoche AA, Pfaller AY, Nencka AS, Koch KM, et al. Cerebral blood flow alterations in acute sport-related concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1227–36. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meier TB, Bellgowan PS, Singh R, Kuplicki R, Polanski DW, Mayer AR, et al. Recovery of cerebral blood flow following sports-related concussion. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:530–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]