Abstract

Introduction:

The aim of this systematic review is to compare chemotherapeutic agents commonly used in treating recurrent urinary infection in nonpregnant women by their efficacy, tolerability, adverse effects, and cost employing network meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods:

We used three online databases, i.e., PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane Central Registry of Clinical Trials. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the use of prophylactic chemotherapeutic agents used in treating nonpregnant women with recurrent urinary tract infections (RUTIs) published between 2002 and 2016 were selected. Only published papers in English were assessed for study quality, and meta-analyses were performed using fixed-effects model with NetMetaXL.

Results:

Six RCTs fulfilled the criteria. When all three variables, i.e., efficacy, adverse effects and cost were considered, nitrofurantoin 50 mg once daily for 6 months appears to rank high for prophylaxis against RUTI. When efficacy was the only factor, fosfomycin had the highest superiority compared to D-mannose, nitrofurantoin, estriol, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and cranberry juice, respectively. However, fosfomycin was also ranked highest by adverse events. When cost alone is considered, nitrofurantoin appeared the most cost-effective agent while placed third for efficacy alone.

Conclusion:

Selecting appropriate chemotherapeutic agents for RUTI will need to factor in effectiveness, adverse effects, and cost. While it is difficult to select an ideal drug, evaluation using network analysis may guide choice of medication for best practice.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) refers to infection involving urethra, bladder, ureters, and kidneys. Lower UTI includes infection of the urethra and bladder and may be asymptomatic but is often a common complaint, especially in older women. When symptomatic, it presents with increased frequency of micturition with or without dysuria and with or without suprapubic discomfort. However, infection of the upper urinary tract is more severe resulting in pyelonephritis with high morbidity.[1] Recurrent UTI (RUTI) is said to be present when more than one infection occurs in 6 months or more than two infections in 1 year. RUTI is more common in women. The prevalence of RUTI varies from 40% - 50% among women. Women would experience at least one episode of UTI in their lifetime, 25% among those would suffer RUTI within 6 months and about 40% within a year.[2] Conventional teaching identifies risk factors for RUTI as being related to previous history of RUTI, frequency of sexual intercourse, new sexual partner, anomalies of the urinary tract, menopause, and exposure to oral contraceptive pills. Estrogen deficiency seen in postmenopausal women affects not only the genital tract but also the urethra and bladder mucosa contributing to RUTI. Other factors implicated are obesity and previous history of hysterectomy.[3,4,5]

Although robust evidence is lacking, clinical guidelines for the management of RUTI recommend hydration as a useful measure. Consumption of up to 1.6 L/day has been advised with additional measures such as voiding as soon as urge is experienced and postcoital voiding. Numerous additional measures have been in vogue without strong clinical evidence ranging from short- and long-term low-dose antimicrobials, cranberry juice, and estrogen therapy for menopausal women with atrophic vaginitis. Use of spermicides or diaphragm as contraception has been implicated for UTI and RUTI.[6,7]

Prolonged low-dose chemotherapeutic agents have been traditionally used as prophylaxis in reducing RUTI.[8,9] These regimes include once-daily treatment using nitrofurantoin monohydrate (50–100 mg), ciprofloxacin (125 mg), trimethoprim (TMP) (100 mg), or TMP–sulfamethoxazole (SMX) (40 mg TMP/200 mg SMX), respectively, for 6 months. Conventionally, efficacy of prophylactic effect is re-evaluated after 6–12 months based on recurrence of symptoms and demonstration of uropathogens on urine examination.[9,10,11] Nonpharmacological agents have been in practice; currently, cranberry tablets or juice and D-mannose are in vogue. Although more robust studies are required, Fu et al.'s updated meta-analysis appear to support the use of cranberry tablets.[12] Unfortunately, research in comparing chemotherapeutic agents commonly used in treating RUIT lacks homogeneity or sturdy techniques of research methodology. Network meta-analysis is an extension of standard pairwise meta-analysis. The advantage of the latter is that by including multiple pairwise comparisons across a range of interventions, effectiveness of multiple treatment alternatives can be compared. Traditional reports compare new drugs with placebo or standard care, but not against each other. Network analysis hopefully will help bridge this gap as it permits pitching the efficacy of one drug against each other directly or indirectly (head-to-head comparison) and also against placebo as a novel means of evaluating superiority of chemotherapeutic agents used in treating RUTI.[13]

We performed a systematic review to look at the efficacy, tolerability, and adverse effects of commonly used chemotherapeutic agents in RUTI.[14] The objective is to compare selected commonly used chemotherapeutic agents so as to determine their superiority and to rank them according to selected variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

A literature search was done using three online databases, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane Central Registry of Clinical Trials. The MeSH terms used were “recurrent urinary tract infection,” “non-pregnant woman,” “postmenopausal,” “antimicrobial,” and “randomized controlled trials.” Only studies published between 2002 and 2016 were retrieved. Three researchers performed an independent literature search on each database. The abstracts of the relevant articles were extracted and scrutinized to see if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria before retrieving the full articles for our study. The “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols 2009 (PRISMA 2009)” was followed. Consensus for inclusion for study, data extraction, and data entry was reached in consultation with the lead author.

Study selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were women aged more than 18 years of age, including postmenopausal women who had attained menopause for more than a year and women with RUTI for more than 2 years with no other lower urinary tract symptoms. Exclusion criteria were women younger than 18 years of age, pregnant state, having UTI for the first time, those with indwelling urinary catheter, associated pelvic organ prolapse, neurological factors affecting the lower urinary tract, or any other secondary symptoms. Only RCTs were included.

Data extraction

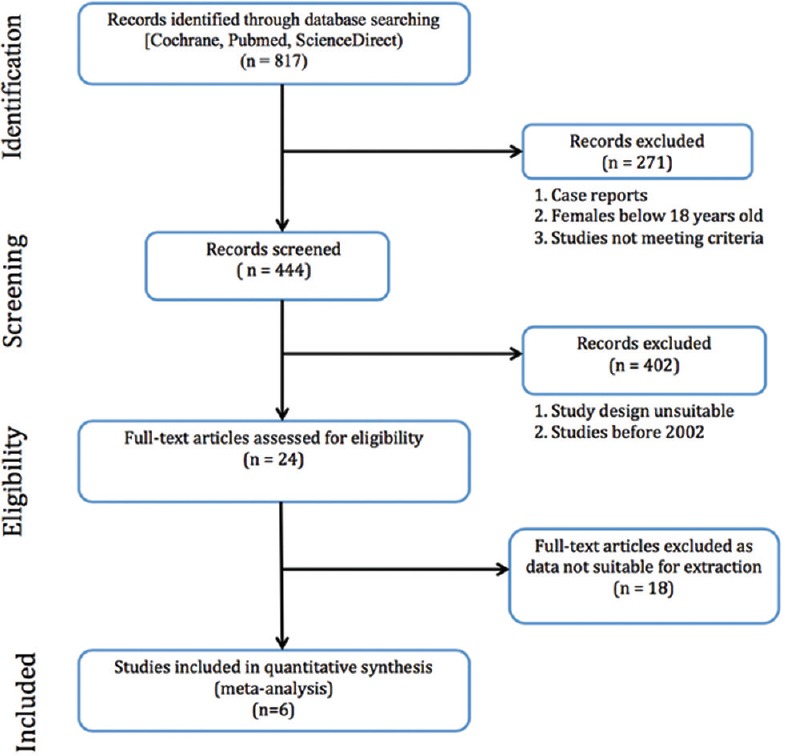

Suitable RCTs with data published on clinical outcomes of RUTI in women were extracted. Studies were selected in accordance with the PRISMA 2009 criteria [Figure 1]. Network meta-analysis for efficacy and tolerability were then performed using NetMetaXL. We used a Microsoft Excel-based tool called NetMetaXL, a freely accessible tool where we could enter data easily, set model assumptions, and run the network meta-analysis, with the automated results displayed in excel spreadsheet.

Figure 1.

Study design-preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses for protocols 2009 flow chart

Out of 817 papers that were found on cited databases on initial keyword insertion, 24 articles were selected after reading the abstract of the studies. Eighteen papers were rejected as they were published before 2002, did not fit our inclusion and exclusion criteria, or data published in these papers were not suitable for our method of analysis. After further scrutiny, six papers were finally selected, and results were then entered into the software [Tables 1 and 2]. Each of the original articles was studied independently by each of the three authors and details were entered into a table of variables. After this initial step, all three met to look for concordance. When there was the lack of agreement, the lead author was consulted for decision for inclusion.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the review

| Year of study | Type of study | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Sample size | Method | Strength | Limitation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kranjcec, et al.[21] | 2013 | Randomized controlled trial | Age over 18 years, positive history of recurrent cystitis | Pregnant, breastfeeding, trying to conceive, past symptoms of upper UTI and symptoms of SIRS, history of urinary tract anomalies, interstitial cystitis or diabetes, taking hormone therapy, contraception had previously received antibiotic prophylaxis | n=308; 103 in D-mannose group; 103 in nitrofurantoin group; 102 in placebo group | D-mannose group received 2 g of D-mannose powder diluted in 200 ml of water once daily in the evening for 6 months; nitrofurantoin group received 50 mg of nitrofurantoin once daily in the evening for 6 months; placebo group did not receive anything for 6 months | Analysis for projected UTI recurrence rate of 30% in no prophylaxis group was done | It was not blinded and the total number of recurrences per patient could not be calculated since we did not re-enter the patients into the study after the antibiotic treatment of recurrent infection |

| McMurdo, et al.[22] | 2008 | Randomized controlled trial | Community-dwelling women aged ≥45 years with at least two antibiotic-treated UTIs or episodes of cystitis in the previous 12 months | Previous urological surgery, stones or anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract, urinary catheter, diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised, pyelonephritis, severe renal blood dyscrasia, symptomatic UTI at baseline, resident in institutional care, on long-term antibiotic therapy, on warfarin therapy, regular cranberry consumers, childbearing potential | n=137; 69 in cranberry group; 68 in TMP-SMX group | Cranberry group received 200 capsules containing 500mg of cranberry extract for 6 months; TMP-SMX group received 200 capsules containing 100mg of trimethoprim for 6 months | The target of 120 participants for the trial was met, as well as the primary and secondary outcomes. Therefore, there is good internal validity | Did not have a placebo group |

| Beerepoot et al.[23] | 2011 | Randomized controlled trial, double-blind, double-dummy | Premenopausal women, 18 years of age or older, with a medical history of at least three symptomatic UTIs in the year preceding enrolment | Symptoms of a UTI, use of antibiotics or cranberry in the previous two weeks, relevant interactions with existing medication or contraindications for TMP-SMX or cranberries, pregnancy, breastfeeding and history of renal transplantation | n=221; 110 in TMP-SMX group; 111 in cranberry group | TMP-SMX group took one tablet with 480 mg TMP-SMX at night and one placebo capsule twice daily for 12 months; cranberry group took one capsule with 500 mg cranberry extract twice daily and one placebo tablet at night for 12 months | Relatively long intervention period of 12 months; inclusion of a washout period after the discontinuation of the study medication; thorough microbiologic testing and rigorous analyses were performed; effect of long-term (antibiotic) prophylaxis on the indigenous flora was assessed | Only premenopausal women were included in this study; target of 280 participants was not reached; high resistance rates at baseline and the relatively high background incidence of UTIs in the study population might have influenced the success rates; high withdrawal rates (≤58%); did not confirm that all women took the cranberry prophylaxis (antibacterial activity is present in the urine of TMP-SMX group) |

| Raz, et al.[24] | 2003 | Randomized trial, double-blind, double dummy | Postmenopausal women who had a history of recurrent UTI | History of any usage of HRT in the previous year, known malignancy patients, patients with vaginal bleeding, active or recent thromboembolic disease, usage of indwelling catheter, known urinary retention, long-term recipient of antibiotic treatment for the past 3 months | n=171; 86 in estriol group ; 85 in NM group | Estriol group received an estriol-containing vaginal pessary daily for 2 weeks and then once every two weeks for 9 months together with oral placebo capsules each night during the same period; NM group received a capsule of NM nightly for 9 months together with a placebo vaginal pessary daily for two weeks, followed by a placebo pessary every two weeks for the remainder of the 9-month period | Result showed that women who received NM had fewer episodes of bacteriuria as compared to those using estriol containing pessaries as compared to other papers | Do not understand estrogen’s ability to restore the population of lactobacilli and reduce pH |

| Barbosa-Cesnik, et al.[15] | 2011 | Prospective, randomized, Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Women 18-40 years of ages, had more than three urinary symptoms, would be in Ann Arbor for the next 6 months | Antibiotic treatment over the last 48 h, hospitalization, or catheterization within the previous two weeks, kidney stones, diabetes, pregnancy or cranberry allergy, and a negative urine culture result | n=319; 155 in cranberry group; 164 in placebo group | Cranberry juice group were given 8oz of 27% low-calorie cranberry juice cocktail twice per day for 6 months; placebo group were given eight oz of placebo juice twice per day for 6 months | This study is double-blinded and randomized; recurrence rate is lower than expected right before the study was done; study juice was delivered to participant’s home every one to two weeks starting on the day of enrollment to promote compliance | No validated test for a biological marker of cranberry juice consumption, and blinded assessments of potential tests did not distinguish between groups, compliance was assessed based on self-report; smaller sample study size than expected (expecting 200 in each group); low compliance rate (many patients dropped out during the study) |

| Ruxer et al.[25] | 2006 | Randomized controlled trial | Type 2 diabetic women presenting with dysuric symptoms, not taking any antibacterials within 1 month before inclusion, aged 50-70 years old, suffering from at least three recurrent episodes of urinary tract infection in the past year, diagnosed with significant bacteriuria and whose pathogen cultured from the urine was sensitive to both Nitrofurantoin and Fosfomycin | Serum creatinine above 1.5 mg/dl, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels of more than twice the upper limit of normal, bilirubin exceeding 1.3 mg/dl, sonographic changes in the hepatic and renal parenchyma and nephrolithiasis, women with a history of renal or hepatic disorders, late diabetic complications, hematopoietic system disorders, and alcoholism | n=50; 25 in fosfomycin group; 25 to nitrofurantoin group | Fosfomycin group received fosfomycin granules dissolved in a glass of boiled water and were given 2 h after dinner and voiding, every thirty days for 6 months; Nitrofurantoin group received nitrofurantoin capsules 100 mg every 12 h (at breakfast and dinner time) for the first seven days followed by 100 mg once daily at dinner time for 6 months | Study revealed only one case of adverse reactions associated with NF, namely vertigo; high treatment compliance, only three patients dropped out of study during the duration of six months | Small sample size (50 women) |

The heterogeneity of the studies is illustrated by differing sample size and different regimes used in the treatment of rURI. Compliance to therapy was only 45% in Beerepoot’s study. NM=Nitrofurantoin macrocrystal, UTI=Urinary tract infection, SIRS=Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, TMP-SMX=Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Table 2.

Studies reviewed by endpoint and adverse events

| Endpoint | Mean duration of follow-up | Efficacy comparison | Safety data (adverse effect) | Treatment compliance | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kranjcec, et al.[21,22] | The number of patients in each group without recurrent UTI after 6 months | 6 months | 85.4% in D-mannose powder group; 79.6% in nitrofurantoin group; 39.2% in placebo group; P=0.001 | There is eight patient in D-mannose group (7.8%) versus 29 patients in nitrofurantoin group (27.2%) | 100% compliance rate for all groups | D-mannose powder shown effective in preventing UTI during 6-month prophylaxisThe recurrence rate did not differ between the patient taking standard prophylaxis and those who took D-mannose powder |

| McMurdo, et al.[22] | Symptomatic UTI treated by the GP | 6 months | 64% in cranberry group; 79% in TMP-SMX group; P=0.084 | Six patients in cranberry group (9%)Eleven patients in the trimethoprim group (16%) | 91% from the cranberry group; 84% from the trimethoprim group | Trimethoprim had a very limited advantage over cranberry extract in the prevention of recurrent UTIs in older women and had more adverse effects |

| Beerepoot et al.[23] | The mean number of symptomatic UTIs over 12 months | 12 months | 29% in TMP-SMX group; 21.8% in cranberry group | Five patients in TMP-SMX group (4.5%)Six patients in cranberry group (5.4%) | 45.5% for TMP-SMX group; 45.2% for cranberry group | In premenopausal women with rUTIs, TMP-SMX, 480 mg once daily, is more effective than cranberry capsules, 500 mg twice daily, for the prevention of rUTIs |

| Raz, et al.[24] | Absence of symptomatic/asymptomatic episodes of bacteriuria | 9 months | 32.6% in estriol group; 48.2% in NM group; P=0.01 | 10.5% in estriol group (nine patients) and 16.5% in NM group (fourteen patients) | 93.0% for estriol group; 87.0% for NM group | Use of the estriol-containing vaginal pessary studied here failed to prevent new episodes of bacteriuria in elderly women with recurrent UTI as effectively as did NM therapy |

| Barbosa-Cesnik, et al.[15] | Recurrence of UTI after starting of study/6 months after | 6 months | 19.3% for cranberry group; 14.6% placebo; P=0.21 | Not statedGastrointestinal symptoms were reported twice as frequently for those receiving placebo than cranberry, with the differences statistically significant in months three and five | 75.6% for cranberry group; 76.6% in placebo group | Those drinking 8oz of 27% cranberry juice twice daily did not experience a decrease in the 6-month incidence of a second UTI, compared with those drinking a placebo |

| Ruxer et al.[25] | Complete resolution of dysuric symptoms and eradication of the uropathogen in the follow-up urine bacteriology | 6 months | 96% in fosfomycin group; 92% in nitrofurantoin group | No clinically relevant adverse reactions or significant laboratory abnormalities reported in fosfomycin groupOne reported after 6-month follow-up with vertigo, most likely related to study drug | 96% in fosfomycin group; 88% in NF group | Nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin are effective chemotherapeutic agents both in the treatment and prevention of recurrent UTIs in type 2 diabetic women. Long-term use of fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin is associated with a low risk of adverse drug reactions |

UTIs=Urinary tract infections, NM=Nitrofurantoin macrocrystal, TMP-SMX=Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, rUTIs=Recurrent urinary tract infections, GP=General practitoner, NF=Nitrofurantoin

RESULTS

Six studies between 2002 and 2016 fulfilled the criteria and reviewed. The mean age for RUTI in this review was 57.7 years (data from the study by Barosa-Cesnik et al.[15] who included 18–40 years' age group and had excluded perimenopausal women).

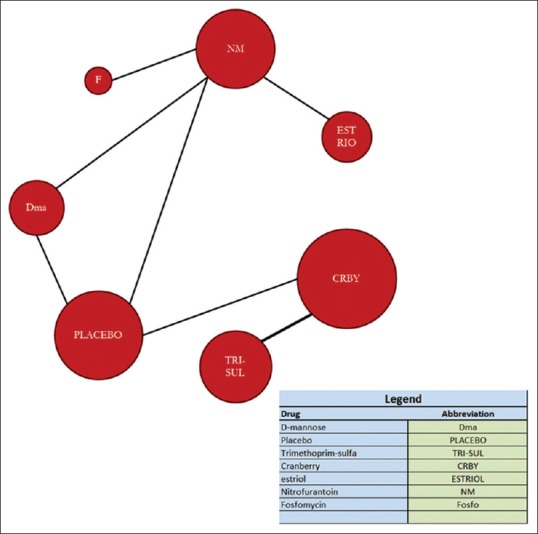

The six RCTs included in this analysis have been summarized and tabulated in Tables 1 and 2. Based on the papers we had obtained, nitrofurantoin plays a more major role as being one of the best drugs used for RUTI, as compared with placebo and other drugs. Figure 2 shows the figurative size of samples used as a head to head comparison with the placebo in all papers. The nodes and edges (connections) show both direct and indirect comparisons. Size of bubble and thickness of the connections indicate size and strength of head-to-head comparisons. These have implications in interpretations of the results and impact on variables of agents studied for the treatment of RUTI.

Figure 2.

Network analysis of drugs used treatment by sample size

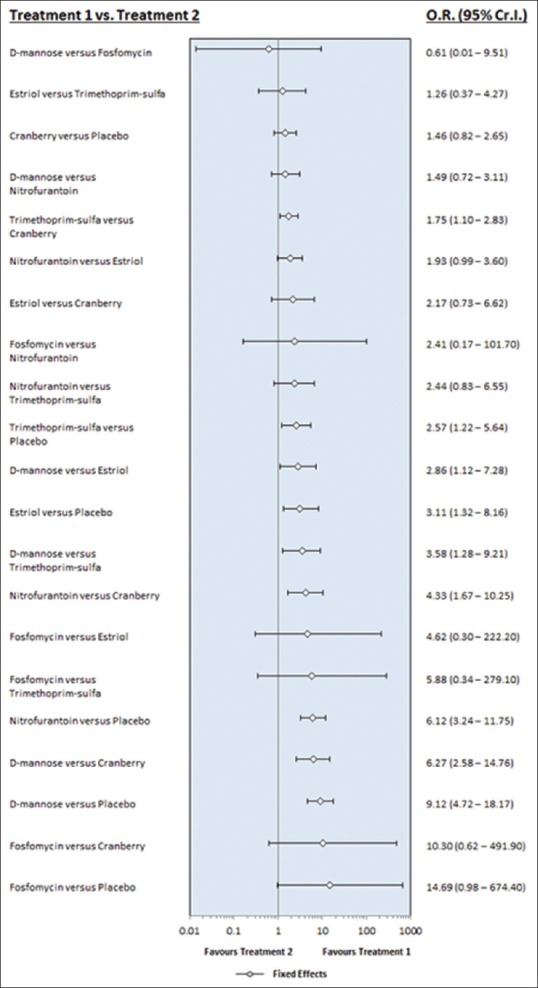

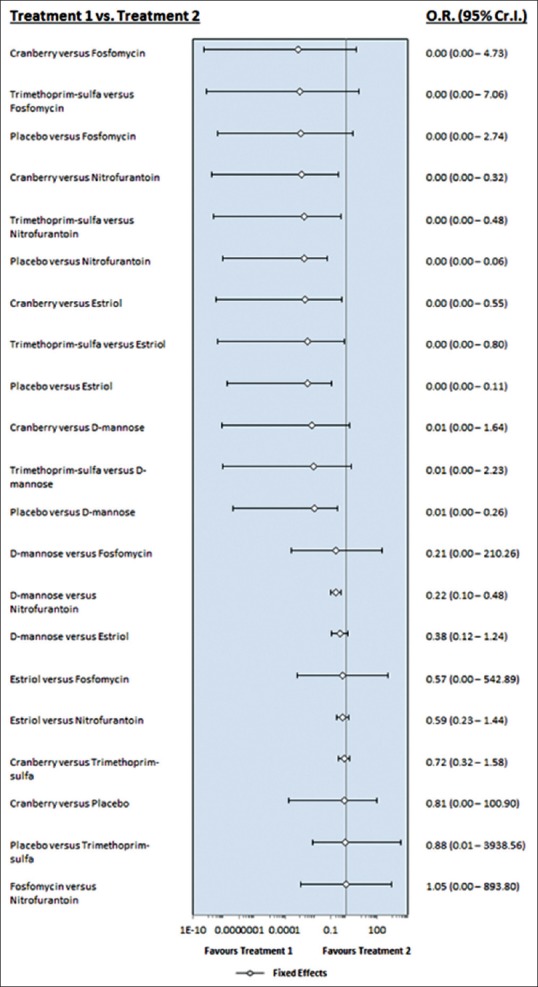

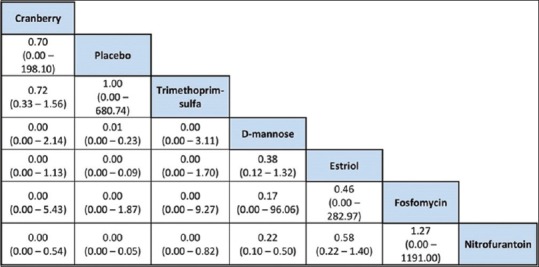

D-mannose shows the highest efficacy with fosfomycin second and nitrofurantoin third [Figures 3 and 4]. The limiting factor in its selection would perhaps be the cost. Apart from D-mannose, fosfomycin 3 g once monthly was effective prophylaxis for RUTI. However, the result might be confounded by heterogenecity as only one RCT used fosfomycin; this is limited by the sample size. Despite its efficacy, fosfomycin appears to rank highest for adverse effects compared to the other agents. These included diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, skin rash, heartburn, vaginitis, headache, chills, and asthenia. However, these were tolerable as no participants dropped out from the trial, and the compliance rate was 100%.

Figure 3.

Comparison of all drug intervention in terms of efficacy. Heterogenecity = 0.5125 95%CI (0.00122–1.876)

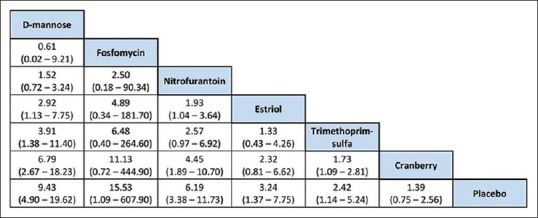

Figure 4.

League table of drugs used in the recurrent urinary tract infection. D-mannose ranks highest with fosfomycin second and nitrofurantoin third

Nitrofurantoin ranked third in efficacy when prescribed at 50 mg once daily. Common side effects included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and skin allergies. Some rare side effects such as anaphylactic reactions in the elderly, asthma-like bronchial hyperreactivity, pulmonary edema, drug-induced fever, headache, vertigo, depression, increased activity of serum aminotransferases, hematologic abnormalities, and symptoms of peripheral polyneuropathy have been reported. However, there were no dropouts during the trial, and the participants were able to complete the course of nitrofurantoin as the adverse effects were tolerable. Cranberry is low down in the league table. As expected, the need for therapy with some form of chemotherapeutic agent is indicated by the lowest rank for placebo. Clinical factors such as age, lifestyle, and pattern of disease and acceptability will need to be factored in.

In terms of adverse effects of each intervention for RUTI, D-mannose was ranked the highest, with cranberry and estriol in the lower rankings as seen in Figure 5, where we had a forest plot comparing all interventions in terms of their adverse events. Cranberry is ranked the highest in the league table in Figure 6 for least adverse event, apart from the placebo itself. Figures 5 and 6 show adverse effects of all chemotherapeutic agents in the review. Apart from placebo, cranberry is ranked highest in the league table [Figure 6] with nitrofurantoin lowest. As stated above, there were no dropouts when nitrofurantoin was prescribed.

Figure 5.

Comparison of all intervention in terms of adverse effects. By way of adverse effects, D-mannose ranks highest with estriol and cranberry lower. Better than estriol

Figure 6.

League table of drugs in terms of adverse effects. Apart from placebo, cranberry is ranked highest in the league table [] with nitrofurantoin lowest indicating the latter is associated with more adverse effects than others though dropout rate was not an issue

The cost of each treatment for a duration of 6 months is based on the National British Formulary and is at best, an estimate amount [Table 3]. Nitrofurantoin tablet of 50 mg is the cheapest drug in the review. D-Mannose and TMP-SMX are ranked the most expensive total cost; the total expenditure for a course over 6 months was 85.05 USD and 112.55 USD, respectively. Other treatment options such as estriol pessary, cranberry juice, and fosfomycin tablets ranged between 11.04 USD and 39.24 USD.

Table 3.

Cost of the prophylaxis of chemotherapeutic agents for 6 months duration

| Type of prophylaxis agent | Recommended dosage for 6 months | Cost per pack | Total cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrofurantoin tablet 50mg | Once daily for 6 months | £1.84/pack (28 tablets) | £5.52 |

| Estriol pessary 500 mg | Once daily for 2 weeks, then once a fortnight subsequently (25 pessaries) | £4.92/pack (15 pessaries) | £8.20 |

| Cranberry extract capsule 500 mg | Once daily for 6 months | £11.96/pack (100 capsules) | £21.53 |

| Fosfomycin sachet 3mg | Once monthly for 6 months | £4.86/sachet | £29.16 |

| D-mannose powder 2gm | Once daily for 6 months | £34.99/pack (200gm) | £63.00 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole tablet 480 mg | Once daily for 6 months | £13.83/pack (28 tablets) | £82.98 |

Proportionately D-mannose and Trimethoprin-sulfmethaxazole rank high (63.00 vs, 83.00). Nitrofurantoin is relatively a cheap drug and based on tolerability and efficacy. Prices are based on British Formulary (2015) and are at best an estimate

DISCUSSION

Based on the results as shown, nitrofurantoin 50 mg once daily for 6 months appears to rank highest based on efficacy, cost, and adverse effects for chemotherapeutic prophylaxis for RUTI among nonpregnant women. In terms of efficacy comparison among all interventions, fosfomycin and D-mannose appeared to be more superior when compared to other treatment modalities. “Fosfomycin however does show way more adverse events as compared to the other treatment modalities.” After considering cost of the agents, nitrofurantoin appears most cost-effective agent, though placed third for efficacy.

Price et al., in their review of 2016, included ten studies, which outnumbered ours.[13] However, they included older RCTs (1977–2007), whereas we confined our review to 2002–2016. Changing prescription trends will impact on reviews if we compare old and newer studies. Further, treatment practice will also affect uropathogen proliferation trends and antimicrobial drug resistance. Unlike our review, Price et al. included men in the analysis and women with underlying type two diabetes mellitus. These differences prevented us from comparing with their study.

In another meta-analysis published in 2009, Matthew et al. included five studies that used the same antimicrobials as in our review, with the same dosage schedule, adding more strength to their paper due to the good homogeneity and also more direct comparisons between each drug regimen. However, in their study, only five RCTs were used, and there were limited number of patients. Their studies extended for a longer period from 1970 to 2010, again including older studies.

Three main risk factors for RUTI in women of all ages are an increased frequency of sexual intercourse, the use of a spermicide and diaphragm as contraception, and estrogen deficiency with consequent effect on both the vagina and periurethral structures.[15] Traditional advice for sexually active women is to void immediately after intercourse to lessen the risk of coitus-related introduction of bacteria into the bladder, although this is not supported by robust evidence.[16] Women in the postmenopausal age (mean in this review is 57.7 years) RUTI is probably explained by the importance of estrogen deficiency playing a vital role in maintaining the integrity of mucosa of urethral, bladder, and vaginal epithelia and vaginal flora. Estrogen deficiency is associated with increased vaginal pH, decreased endogenous vaginal microflora, and increased incidence of pelvic organ prolapse due to endopelvic fascia and pelvic floor muscle weakness.[3]“Postmenopausal women who applied topical low dose vaginal estrogen cream for two weeks duration has shown to have lower risk of rUTI as well.”[15,17]

Continuous administration of low-dose chemotherapeutic agents as prophylaxis for RUTI has been reviewed and has benefits as shown in this network analysis. If left untreated, women are at a risk for RUTI and upper UTI. “The common regimes prescribed varies, namely TMP-SMX 40/200mg once or three times weekly, nitrofurantoin 50-100mg once or three times weekly and Fosfomycin 3g every 10 days for 6 months duration.” In women where UTI is associated with sexual intercourse, postcoital prophylaxis has been recommended. A single-dose nitrofurantoin 50 mg or TMP-SMX 40/200 mg after sexual intercourse has been reported.[15]

In this review, D-mannose and fosfomycin ranked high for efficacy although adverse effects were tolerably higher in the latter. Nitrofurantoin is an old but useful drug because of its cost. When used in doses of 50 mg daily, it was the third most effective prophylaxis. However, it also ranked second among agents with most adverse effects.

Nonpharmacological agents such as cranberry juice and D-mannose have shown success in treating RUTI and may be useful alternatives. One study reported lower rates of UTI recurrence in women who drank 50 mL of cranberry-lingonberry concentrate daily for 6 months although the mechanism of action of cranberry juice is conjectural.[12,18] Cranberry contains hippuric acid and is known to be bacteriostatic. Another mechanism suggested is its ability to suppress Escherichia coli fimbriae by proanthocyanidins (tannins). The latter detach anchoring uropathogen from bladder wall mucosa.[16]

A recent Cochrane review found no substantial reduction of risk with cranberry administration but after removal of an outlier demonstrated relative risk 0.58 (confidence interval 0.39–0.86) with optimal doses.[15] Probiotics as effective prophylactic measures have not been established.[19]

D-mannose powder 2 mg once daily, a nonpharmacological simple sugar agent, appears to show reasonable efficacy as prophylaxis for RUTI, limited by its cost compared to nitrofurantoin. D-mannose is found in several fruits and is also produced in our body. It is produced by oxidation of mannitol. The chemical structure of D-mannose causes it to adhere to E. coli bacteria causing dislodgement of E. coli from the mucosa.[20]

The software used for this study is NetMetaXL, which offers a wide set of methods to interpret and visualize various interventions for the same disease that are studied separately under different RCTs with the same outcome comparatively. The processes used in this software allow us to infer the difference in strength and weaknesses between various interventions that may or may not have been studied when direct comparison of treatment schedules is done. This particular method offers advantages over regular pairwise meta-analysis as it borrows the strengths from indirect evidence to ascertain all treatment comparisons and pit different interventions against each other as in a head-to-head RCT. Using league tables to demonstrate ranking by tolerability and efficacy appears to be useful to clinicians in selection of chemotherapeutic agents so as to align to the needs of the patient in need of prophylaxis for RUTI.

Limitations

The main limitation in this review was different endpoints in all the studies we included in the analysis. Lack of sufficient data to fulfill the criteria we set especially from the Year 2002 onwards affected sample size and number of RCTs conducted, especially for the fosfomycin and estriol vaginal pessary group. Thus, the result generated may not represent the true effect on population affected by RUTI. Of the six studies that are used in our analysis, only two studies compared the same prophylactic regimens [Tables 2 and 3]. This affects reliability of our analysis results as the data used are heterogeneous.

Sample size and heterogeneity of the studies were other limiting factors. The cost of the chemotherapeutic agents may differ from country to country; this has to be borne in mind in accepting the comments made in relation to costing.

CONCLUSION

Considering the limitations of this review, nitrofurantoin 50 mg once daily for 6 months appears to rank highest based on efficacy, cost, and adverse effects for chemotherapeutic prophylaxis for RUTI among nonpregnant women. Fosfomycin and D-mannose appear superior in efficacy compared to nitrofurantoin, estriol, TMP-SMX, and cranberry juice. “When comparing Fosfomycin and D-mannose, Fosfomycin showed better tolerability between these two, with Nitrofurantoin still being one with the least adverse effect reported.” After considering the cost of the agents, Nitrofurantoin appears to be most cost-effective agent, though placed third for efficacy.

Acknowledgments

International Medical University (IMU), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.[25]

REFERENCES

- 1.Glass R, Curtis M, Overholt S, Hopkins M. Glass’ Office Gynecology. Vol. 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. Urogynecology and pelvic floor dysfunction; pp. 435–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxman B, Barlow R, D'Arcy H, Gillespie B, Sobel JD. Urinary tract infection: Self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:509–15. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooton TM. Pathogenesis of urinary tract infections: An update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46(Suppl 1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooton TM. Recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthew Glover P. Recurrent urinary tract infections in healthy and non pregnant women. Urol Sci. 2014;25:1. doi: 10.1016/j.urols.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dason S, Dason JT, Kapoor A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infection in women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:316–22. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidance on Management on Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection in Non-Pregnant Women. [cited 2017 July 5]. Available from: https://www.sapg.scot/media/4057/management-of-recurrent-urinary-tract-infectionuti-in-non-pregnant-women.pdf .

- 8.Geerlings SE, Beerepoot MA, Prins JM. Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: Antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial strategies. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenberger P, Hooton TM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(Suppl):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raz R, Gennesin Y, Wasser J, Stoler Z, Rosenfeld S, Rottensterich E, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:152–6. doi: 10.1086/313596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 91: Treatment of urinary tract infections in nonpregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:785–94. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318169f6ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Z, Liska D, Talan D, Chung M. An updated meta-analysis of cranberry and recurrent urinary tract infections in women. FASEB J. 2017;31:1. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.254961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price JR, Guran LA, Gregory WT, McDonagh MS. Nitrofurantoin vs. other prophylactic agents in reducing recurrent urinary tract infections in adult women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:548–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rané A, Dasgupta R. Urinary Tract Infection: Clinical Perspectives on Urinary Tract Infection. London: Springer; 2013. pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbosa-Cesnik C, Brown MB, Buxton M, Zhang L, DeBusscher J, Foxman B, et al. Cranberry juice fails to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection: Results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:23–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jepson R, Craig J, Williams G. Cranberry products and prevention of urinary tract infections. JAMA. 2013;310:1395–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raz R, Colodner R, Rohana Y, Battino S, Rottensterich E, Wasser I, et al. Effectiveness of estriol-containing vaginal pessaries and nitrofurantoin macrocrystal therapy in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1362–8. doi: 10.1086/374341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kontiokari T, Sundqvist K, Nuutinen M, Pokka T, Koskela M, Uhari M, et al. Randomised trial of cranberry-lingonberry juice and Lactobacillus GG drink for the prevention of urinary tract infections in women. BMJ. 2001;322:1571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwenger EM, Tejani AM, Loewen PS. Probiotics for preventing urinary tract infections in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD008772. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008772.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porru D, Parmigiani A, Barletta D, Choussos D. Recurrent urinary infections in adult women: A pilot study with oral D-mannose. Eur Urol Suppl. 2013;12:e894. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kranjčec B, Papeš D, Altarac S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: A randomized clinical trial. World J Urol. 2014;32:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMurdo ME, Argo I, Phillips G, Daly F, Davey P. Cranberry or trimethoprim for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections? A randomized controlled trial in older women. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:389–95. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beerepoot MA, ter Riet G, Nys S, van der Wal WM, de Borgie CA, de Reijke TM, et al. Cranberries vs. antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: A randomized double-blind noninferiority trial in premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1270–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raz R, Colodner R, Rohana S, Rottensterich E, Wasser I, Stamm W. Effectiveness of estriol-containing vaginal pessaries and nitrofurantoin macrocrystal therapy in the prevention of recurrent urinary Tract infection in postmenopausal women. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2003;36:1362–8. doi: 10.1086/374341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruxer J, Mozdzan M, Siejka A, Loba J, Markuszewski L. Fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin in the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections in type 2 diabetic women: A preliminary report. Diabetologia Doswiadczalna I kliniczna. 2006;6(5):277–82. [Google Scholar]