Abstract

Importance

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by hair loss that can impose a substantial psychological burden on patients, including major depressive disorder (MDD), yet many patients report mental health symptoms prior to the onset of AA. As such, there may be an association between MDD and AA that acts in both directions.

Objective

To assess the bidirectional association between MDD and AA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based retrospective cohort study included patients 10 to 90 years of age registered with The Health Improvement Network in general practices in the United Kingdom between January 1, 1986, and May 16, 2012. Statistical analysis was conducted from August 17, 2017, to April 23, 2018. To assess the risk of AA, the following 2 cohorts were defined: patients with an incident diagnosis of MDD (exposure) and a reference general population cohort. To assess the risk of MDD, the following 2 cohorts were defined: patients with an incident diagnosis of AA (exposure) and a reference general population cohort. Person-time was partitioned into unexposed and exposed time in the exposure cohorts.

Main Outcomes and Measures

In the analysis of the risk of AA, development of incident AA during follow-up was considered the main outcome measure. In the analysis of the risk of MDD, development of incident MDD during follow-up was considered the primary outcome measure.

Results

In the analysis of the risk of AA, 405 339 patients who developed MDD (263 916 women and 141 423 men; median age, 36.7 years [interquartile range, 26.6-50.5 years]) and 5 738 596 patients who did not develop MDD (2 912 201 women and 2 826 395 men; median age, 35.8 years [interquartile range, 25.3-52.6 years]) were followed up for 26 years. After adjustment for covariates, MDD was found to increase the risk of subsequently developing AA by 90% (hazard ratio, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.67-2.15; P < .001). Antidepressants demonstrated a protective effect on the risk of AA (hazard ratio, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.53-0.62; P < .001). In the analysis of the risk of MDD, 6861 patients who developed AA (3846 women and 3015 men; median age, 31.5 years [interquartile range, 18.2 years]) and 6 137 342 patients who did not develop AA (3 172 371 women and 2 964 971 men; median age, 35.9 years [interquartile range, 27.0 years]) were followed up for 26 years. After adjustment for covariates, AA was found to increase the risk of subsequently developing MDD by 34% (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.23-1.46; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

These temporal analyses suggest that, while patients with AA are at risk for subsequently developing MDD, having MDD also appears to be a significant risk factor for development of AA, with antidepressant use confounding this risk.

This cohort study of over 6 million patients uses data from The Health Improvement Network in the United Kingdom to assess the bidirectional association between major depressive disorder and alopecia areata.

Key Points

Question

Is there a bidirectional association between major depressive disorder and alopecia areata?

Findings

This cohort study of over 6 million patients found that patients with major depressive disorder were at a 90% increased risk of developing alopecia areata and that antidepressants have a protective effect on this risk. Patients with alopecia areata had a 34% increased risk of developing major depressive disorder.

Meaning

Alopecia areata can affect mental health, and in turn mental illness can affect the development of alopecia areata; this bidirectional association suggests common underlying inflammatory and genetic susceptibilities between the brain and skin that require further study.

Introduction

It is well established that hair loss due to alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune skin disease,1 affects patients psychologically in a negative way, increasing the risk of developing major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, patients often suggest the opposite scenario in which perhaps their AA developed because they were depressed. Animal models support this theory, showing that stress, a well-documented inciting factor for MDD,3,4 can lead to immune dysregulation and conceivably provide a platform for autoimmune diseases such as AA to develop.5 However, to our knowledge, very few human-based studies on these associations have been performed.

Alopecia areata and MDD may share similar HLA associations.6,7 Furthermore, MDD may have associations with systemic immune function, most notably by altering serum levels of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor.8 If MDD shares similar serum inflammatory patterns and HLA associations with established autoimmune diseases such as AA, there is biological plausibility that MDD may increase the risk of developing AA. Given the challenges in studying such a topic experimentally, health records represent an important tool that can be used to establish clinical temporality between MDD and AA. Thus, we conducted 2 population-based cohort studies to elucidate the bidirectional association between MDD and AA.

Methods

Full methods are available in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. This study was prepared according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.9 Ethics approval was obtained from IMS Health (United Kingdom) and the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary. Patient consent was waived for this study as all data were deidentified.

Data Source

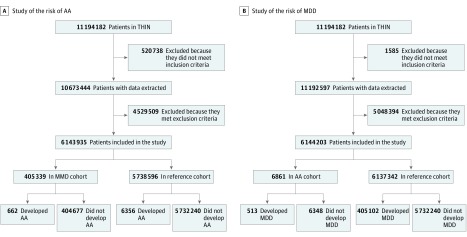

The Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic medical records database was used; THIN contains general practice medical records from approximately 12 million individuals in the United Kingdom with up to 26 years of follow-up (between January 1, 1986, and May 16, 2012). All individuals 10 to 90 years of age were identified in THIN (Figure).

Figure. Study Flow Diagrams.

A, Flow diagram of individuals for the study of the risk of alopecia areata (AA). B, Flow diagram of individuals for the study of the risk of major depressive disorder (MDD). THIN indicates The Health Improvement Network.

Study Population, Exposure, and Outcomes

Risk of AA

Patients with an incident code for MDD (exposure) were assigned to the MDD cohort at the time of their incident code, while all other patients (as well as pre-MDD person-time) were considered in the reference cohort. Patients were followed up until development of AA (outcome) or censoring.

Risk of MDD

Patients with an incident code for AA (exposure) were considered in the AA cohort, while all other patients were considered in the reference cohort. Patients were followed up until development of MDD (outcome) or censoring.

Covariates

For risk of AA, age, sex, alcohol use, smoking, socioeconomic status (determined by use of the Townsend Deprivation Index), medical comorbidities (determined by use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index), and antidepressants were considered as covariates. For risk of MDD, age, sex, medical comorbidities (determined by use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index), and local corticosteroid therapy were considered as covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from August 17, 2017, to April 23, 2018. For both studies, a comparison of covariates at baseline was performed. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and assess effect modification and confounding in each study, as described elsewhere10 and in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. A model adjusting for all covariates and an unadjusted model were constructed for each study. Incidence rates (IRs) of AA among individuals using antidepressants in each cohort were compared. Details on the sensitivity analyses that were conducted can be found in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata MP, version 13.1 (Stata Corp). All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Risk of AA

Compared with the individuals in the reference cohort (n = 5 738 596), the individuals in the MDD cohort (n = 405 339) were older, were more likely to be female (263 916 [65.1%] vs 2 912 201 [50.7%]; P < .001), were more likely to be current smokers (105 543 [26.0] vs 1 141 350 [19.9]; P < .001), were more likely to be nonusers of alcohol (242 528 [59.8%] vs 3 188 567 [55.6%]; P < .001), were more likely to have a lower socioeconomic status (62 765 [15.5%] vs 760 359 [13.2%]; P < .001), were more likely to have at least 1 medical comorbidity (89 830 [22.2%] vs 1 111 882 [19.4%]; P < .001), and were more likely to use antidepressants (357 844 [88.3%] vs 1 064 658 [18.6%]; P < .001) (Table 1). Overall, 662 individuals in the MDD cohort (0.2%) developed AA (IR, 25.6 per 100 000 person-years) compared with 6356 individuals in the reference cohort (0.1%; IR, 13.1 per 100 000 person-years). Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models showed that MDD increased the risk of developing AA by 76% (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.62-1.91; P < .001). After adjustment for all covariates, MDD was found to increase the risk of AA by 90% (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.67-2.15; P < .001) (Table 2). Antidepressants were identified as having a protective effect on AA (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.53-0.62; P < .001) (Table 2), which was demonstrated by the lower IRs among antidepressant users in both cohorts (eTable in the Supplement). Because more patients in the MDD cohort than in the general population cohort used antidepressants (Table 1), the confounding nature of this association led to an increase in the HR with adjustment of greater than 10% (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.23-1.55). There was no evidence of effect modification by any of the covariates or of any violation of the proportional hazards assumption. Sensitivity analyses that included adjustment for body mass index and for exclusion of telogen effluvium found similar results (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Patients With Alopecia Areata, and the General Population.

| Characteristic | Individuals, No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder Cohort (n = 405 339) | Reference Cohort (n = 5 738 596) | |

| Median follow-up time (IQR), y | 5.1 (2.1-9.6) | 6.2 (2.9-12.3) |

| Median age (IQR), y | 36.7 (26.6-50.5) | 35.8 (25.3-52.6) |

| Female sex | 263 916 (65.1) | 2 912 201 (50.7) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 105 543 (26.0) | 1 141 350 (19.9) |

| Ex-smoker | 32 579 (8.0) | 528 880 (9.2) |

| Never | 188 638 (46.5) | 2 882 473 (50.2) |

| Missing | 78 579 (19.4) | 1 185 893 (20.7) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Users | 162 811 (40.2) | 2 550 029 (44.4) |

| Missing | 155 431 (38.3) | 2 210 716 (38.5) |

| Socioeconomic statusb | ||

| 1 | 83 672 (20.6) | 1 242 332 (21.6) |

| 2 | 76 763 (18.9) | 1 103 464 (19.2) |

| 3 | 79 998 (19.7) | 1 109 993 (19.3) |

| 4 | 80 525 (19.9) | 1 051 767 (18.3) |

| 5 | 62 765 (15.5) | 760 359 (13.2) |

| Missing | 21 616 (5.3) | 470 681 (8.2) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexc | ||

| 0 | 315 509 (77.8) | 4 626 714 (80.6) |

| 1 | 65 440 (16.1) | 713 939 (12.4) |

| 2 | 12 020 (3.0) | 158 934 (2.8) |

| 3 | 4304 (1.1) | 60 694 (1.1) |

| ≥4 | 8066 (2.0) | 178 315 (3.1) |

| Antidepressant use | 357 844 (88.3) | 1 064 658 (18.6) |

| Alopecia Areata Cohort (n = 6861) | Reference Cohort (n = 6 137 342) | |

| Median follow-up time (IQR), y | 4.4 (1.9-8.4) | 6.2 (2.9-11.9) |

| Median age (IQR), y | 31.5 (23.4-41.6) | 35.9 (25.5-52.5) |

| Female sex | 3846 (56.1) | 3 172 371 (51.7) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Indexb | ||

| 0 | 5648 (82.3) | 4 936 766 (80.4) |

| 1 | 974 (14.2) | 778 433 (12.7) |

| 2 | 109 (1.6) | 170 868 (2.8) |

| 3 | 29 (0.4) | 64 980 (1.1) |

| ≥4 | 101 (1.5) | 186 295 (3.0) |

| Use of intralesional or potent topical corticosteroids | 912 (13.3) | 280 485 (4.6) |

P < .001 for all comparisons.

Higher number indicates more severe socioeconomic deprivation using the Townsend Deprivation Index.

Higher number indicates more severe or greater number of medical comorbidities.

Table 2. Models for the Risk of Alopecia Areata Associated With Major Depressive Disorder.

| Model | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | ||

| Major depressive disorder | 1.76 (1.62-1.91) | <.001 |

| Multivariable adjusted modela | ||

| Major depressive disorder | 1.90 (1.67-2.15) | <.001 |

| Age | 0.43 (0.40-0.46) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 0.81 (0.75-0.86) | <.001 |

| Socioeconomic statusb | ||

| 2 | 0.99 (0.90-1.10) | .87 |

| 3 | 1.15 (1.04-1.27) | .01 |

| 4 | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | <.001 |

| 5 | 1.43 (1.29-1.59) | <.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.16 (1.07-1.26) | <.001 |

| Alcohol use | 0.93 (0.87-1.00) | .06 |

| Smoking | ||

| Current | 1.43 (1.33-1.54) | <.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.13 (1.01-1.27) | .03 |

| Antidepressant use | 0.57 (0.53-0.62) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Observations with missing data were omitted from the models.

Higher number indicates more severe socioeconomic deprivation using the Townsend Deprivation Index.

Risk of MDD

Compared with the individuals in the reference cohort (n = 6 137 342), the individuals in the AA cohort (n = 6861) were younger (median age, 31.5 vs 35.9 years; P < .001), were more likely to be female (3846 [56.1%] vs 3 172 371 [51.7%]; P < .001), were less likely to have a medical comorbidity (1213 [17.7%] vs 1 200 576 [19.6%]; P < .001), and were more likely to have received local corticosteroid therapy (912 [13.3%] vs 280 485 [4.6%]; P < .001) (Table 1). Overall, 513 individuals in the AA cohort (7.5%) developed MDD (IR, 1298 per 100 000 person-years) compared with 405 102 individuals in the reference cohort (6.6%; IR, 835 per 100 000 person-years). Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models showed that AA increased the risk of developing MDD (HR, 1.49; 95% CI 1.37-1.62; P < .001), which was slightly attenuated after adjusting for covariates (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.23-1.46; P < .001) (Table 3). There was no evidence of effect modification by age or sex, confounding by any covariate, or violation of the proportional hazards assumption.

Table 3. Models for the Risk of Major Depressive Disorder Associated With Alopecia Areata.

| Model | HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Unadjusted model | |

| Alopecia areata | 1.49 (1.37-1.62) |

| Multivariable adjusted modelb | |

| Alopecia areata | 1.34 (1.23-1.46) |

| Age | 0.75 (0.74-0.75) |

| Male sex | 0.53 (0.53-0.53) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.28 (1.27-1.29) |

| Intralesional or potent topical corticosteroids | 1.33 (1.31-1.34) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

P < .001 for all.

Observations with missing data were omitted from the models.

Discussion

Autoimmune disease is proposed to increase the risk of MDD,2 and our results support the association between AA and MDD. This finding highlights the need for clinicians to recognize signs of MDD and initiate early management of patients with AA. Our reciprocal analysis confirmed a bidirectional association in which MDD imposed a 90% increased risk for the later development of AA.

In the diathesis stress model of MDD,11 diatheses are defined as inherent vulnerabilities to mental disorders, which may include biological (eg, genetics), physiological (eg, inflammation), or cognitive factors. Applied stressors interact with diatheses, leading some individuals to develop a mental disorder, such as MDD.3,4,12 Because MDD shares similar genetic and inflammatory signatures with autoimmune disease,6,7,8 it follows that individuals with a susceptibility to MDD may be prone to autoimmune diseases such as AA. Our data from this large population cohort with up to 26 years of follow-up supports this theory. Recently, MDD was shown to increase the risk of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis10; thus, our study adds further support to the concept of a connection between MDD and inflammation.

As additional evidence of a direct association between MDD and development of AA, antidepressants had a protective effect such that patients with MDD who were treated with antidepressants had a reduced risk of AA relative to patients with MDD who were not taking antidepressants. Thus, antidepressants appear to play some role in protecting against AA, especially among patients with MDD, although further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanism. Based on the strong, consistent temporal associations identified in this study and a potential underlying biological theory, a causal association between MDD and AA cannot be ruled out.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. It is possible that some cases of MDD or AA were misclassified in THIN; however, such misclassifications would be expected to occur nondifferentially, and therefore our estimates are likely conservative. Although other factors not considered in the present study may potentially confound the association identified, this possibility is less likely given the fairly robust results with a biopsychosocial framework for the pathogenesis of disease.

Conclusions

We identified a strong bidirectional association between MDD and AA by means of a large population-based cohort study with consideration of numerous covariates and longitudinal follow-up. Although further research is necessary to understand the molecular underpinnings of this association, a biological axis linking the brain and systemic inflammation, including the skin, seems possible.

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results

eTable. Incidence Rates for the Development Of Alopecia Areata Among Patients Prescribed an Antidepressant, Stratified by Cohort

References

- 1.Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1515-1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1103442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46-56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colodro-Conde L, Couvy-Duchesne B, Zhu G, et al. ; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . A direct test of the diathesis-stress model for depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(7):1590-1596. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, et al. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(7):717-728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):5995-5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118355109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petukhova L, Duvic M, Hordinsky M, et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature. 2010;466(7302):113-117. doi: 10.1038/nature09114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weitkamp LR, Stancer HC, Persad E, Flood C, Guttormsen S. Depressive disorders and HLA: a gene on chromosome 6 that can affect behavior. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(22):1301-1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198111263052201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):446-457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewinson RT, Vallerand IA, Lowerison MW, et al. Depression is associated with an increased risk of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(4):828-835. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patten SB. Major depression epidemiology from a diathesis-stress conceptualization. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misiak B, Stramecki F, Gawęda Ł, et al. Interactions between variation in candidate genes and environmental factors in the etiology of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(6):5075-5100. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0708-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results

eTable. Incidence Rates for the Development Of Alopecia Areata Among Patients Prescribed an Antidepressant, Stratified by Cohort