Key Points

Question

Does high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation prolong progression-free survival when added to standard chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer?

Findings

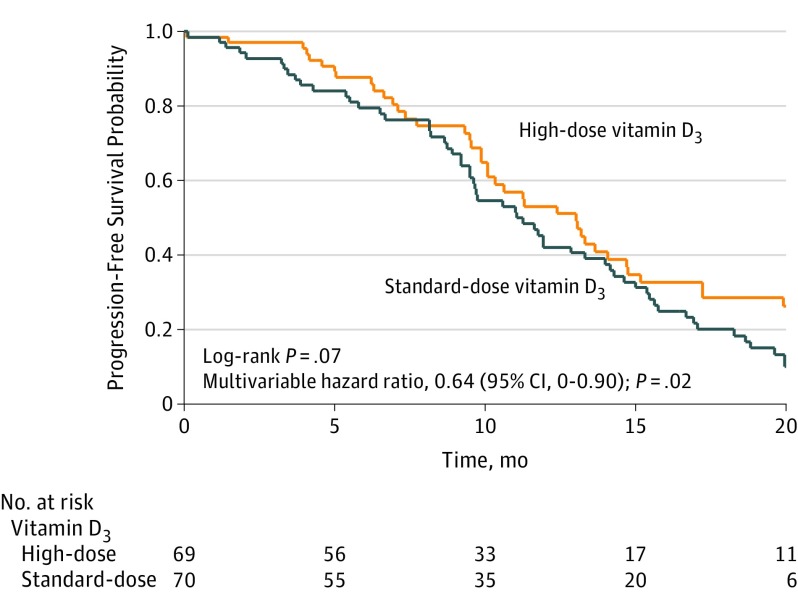

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial that included 139 patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer, treatment with chemotherapy plus high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation vs chemotherapy plus standard-dose vitamin D3 resulted in a median progression-free survival of 13 months vs 11 months, respectively, that was not statistically significant, but a multivariable hazard ratio of 0.64 for progression-free survival or death that was statistically significant.

Meaning

These findings regarding a potential role for high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer warrant further evaluation in a larger multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Abstract

Importance

In observational studies, higher plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels have been associated with improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC).

Objective

To determine if high-dose vitamin D3 added to standard chemotherapy improves outcomes in patients with metastatic CRC.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Double-blind phase 2 randomized clinical trial of 139 patients with advanced or metastatic CRC conducted at 11 US academic and community cancer centers from March 2012 through November 2016 (database lock: September 2018).

Interventions

mFOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab chemotherapy every 2 weeks and either high-dose vitamin D3 (n = 69) or standard-dose vitamin D3 (n = 70) daily until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS) assessed by the log-rank test and a supportive Cox proportional hazards model. Testing was 1-sided. Secondary end points included tumor objective response rate (ORR), overall survival (OS), and change in plasma 25(OH)D level.

Results

Among 139 patients (mean age, 56 years; 60 [43%] women) who completed or discontinued chemotherapy and vitamin D3 (median follow-up, 22.9 months), the median PFS for high-dose vitamin D3 was 13.0 months (95% CI, 10.1 to 14.7; 49 PFS events) vs 11.0 months (95% CI, 9.5 to 14.0; 62 PFS events) for standard-dose vitamin D3 (log-rank P = .07); multivariable hazard ratio for PFS or death was 0.64 (1-sided 95% CI, 0 to 0.90; P = .02). There were no significant differences between high-dose and standard-dose vitamin D3 for tumor ORR (58% vs 63%, respectively; difference, −5% [95% CI, −20% to 100%], P = .27) or OS (median, 24.3 months vs 24.3 months; log-rank P = .43). The median 25(OH)D level at baseline for high-dose vitamin D3 was 16.1 ng/mL vs 18.7 ng/mL for standard-dose vitamin D3 (difference, −2.6 ng/mL [95% CI, −6.6 to 1.4], P = .30); at first restaging, 32.0 ng/mL vs 18.7 ng/mL (difference, 12.8 ng/mL [95% CI, 9.0 to 16.6], P < .001); at second restaging, 35.2 ng/mL vs 18.5 ng/mL (difference, 16.7 ng/mL [95% CI, 10.9 to 22.5], P < .001); and at treatment discontinuation, 34.8 ng/mL vs 18.7 ng/mL (difference, 16.2 ng/mL [95% CI, 9.9 to 22.4], P < .001). The most common grade 3 and higher adverse events for chemotherapy plus high-dose vs standard-dose vitamin D3 were neutropenia (n = 24 [35%] vs n = 21 [31%], respectively) and hypertension (n = 9 [13%] vs n = 11 [16%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with metastatic CRC, addition of high-dose vitamin D3, vs standard-dose vitamin D3, to standard chemotherapy resulted in a difference in median PFS that was not statistically significant, but with a significantly improved supportive hazard ratio. These findings warrant further evaluation in a larger multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01516216

This phase 2 randomized clinical trial compares the effects of high-dose vs standard-dose vitamin D3 added to standard chemotherapy on progression-free survival among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Introduction

Experimental evidence indicates that vitamin D has antineoplastic activity. Binding of vitamin D to its target, the vitamin D receptor, leads to transcriptional activation and repression of target genes and results in induction of differentiation and apoptosis,1 inhibition of cancer stem cells,2 and decreased proliferation,3 angiogenesis,4 and metastatic potential.5 Several prospective observational studies have shown that higher levels of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D, the best indicator of vitamin D status, were associated with decreased risk of colorectal cancer6 and improved survival among patients with colorectal cancer.7,8,9

A prospective analysis of 1043 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were enrolled in a large phase 3 clinical trial sponsored by the National Cancer Institute of first-line chemotherapy plus biological agents (Cancer and Leukemia Group B/Southwestern Oncology Group [CALGB/SWOG] 80405 study) found a high rate of vitamin D deficiency (plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D level <20 ng/mL) with a median 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 17.2 ng/mL.10 Patients with higher levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D prior to chemotherapy had significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival. The median overall survival was 32.6 months (95% CI, 27.7-36.9 months) for those with the highest 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels compared with 24.5 months (95% CI, 21.7-28.6 months) for those with the lowest levels (log-rank P = .01).10

However, observational studies are not able to discern whether higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels play a causal role in improving survival, are simply a surrogate of better health, or a reflection of more favorable disease. Consequently, a double-blind, multicenter, phase 2 randomized clinical trial called SUNSHINE was conducted to test whether vitamin D3 supplementation to raise plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels can improve outcomes in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer.

Methods

Trial Design and Patient Eligibility

This study was a double-blind, multicenter, phase 2 randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of high-dose vitamin D3 compared with standard-dose vitamin D3 when given in combination with standard chemotherapy (the study protocol appears in Supplement 1). The phase 2 design was chosen to demonstrate proof of concept and feasibility of vitamin D supplementation to raise plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institution. An independent data and safety monitoring board provided oversight of the trial. All patients provided written informed consent.

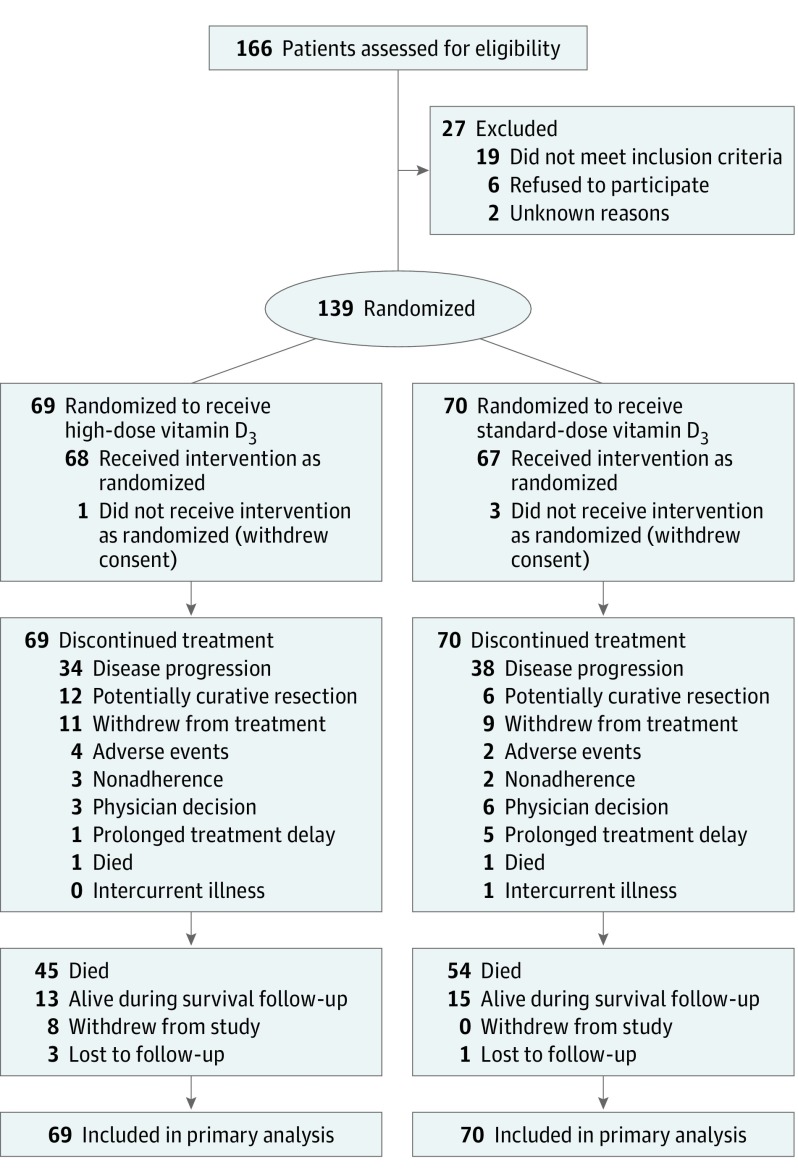

Patients were enrolled at 11 academic and community cancer centers across the United States. Patients were eligible if they had pathologically confirmed, unresectable locally advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum with measurable disease per version 1.1 of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines. Patients were excluded if they received prior treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. However, patients were eligible if they received prior neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation as long as the last dose of treatment was more than 12 months prior to cancer recurrence. Eligible patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, normal baseline organ function, and no evidence of hypercalcemia or conditions predisposing to hypercalcemia (ie, hyperparathyroidism). Patients were excluded if they were taking 2000 IU/d or greater of vitamin D3, had symptomatic genitourinary stones within the past year, or were taking thiazide diuretics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow of Patients Through the Phase 2 Randomized Trial of High-Dose vs Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation.

Intervention

All patients received chemotherapy with a continuous infusion of 2400 mg/m2 of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) over 46 to 48 hours, a bolus of 400 mg/m2 of 5-FU, 400 mg/m2 of leucovorin, and 85 mg/m2 of oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) plus 5 mg/kg of bevacizumab administered intravenously every 14 days per institutional standard of care (1 cycle = 14 days). Bevacizumab was allowed to be omitted during the first cycle and started with cycle 2 at the investigator’s discretion. Patients were randomized by a statistician (H.Z.) using computerized block randomization with a block size of 2 in a 1:1 ratio to concurrent high-dose vs standard-dose oral vitamin D3. The high-dose group received a loading dose of 8000 IU/d of vitamin D3 (two 4000 IU capsules) for cycle 1 followed by 4000 IU/d for subsequent cycles. The standard-dose group received 400 IU/d of vitamin D3 during all cycles (one 400 IU capsule plus 1 placebo capsule during cycle 1 to maintain blinding).

The vitamin D3 capsules (4000 IU and 400 IU) and placebos appeared identical and were made by Pharmavite LLC. Only the statistician and the research pharmacist were unblinded to treatment assignment. Patients were asked to stop all vitamin D– and calcium-containing supplements outside the study intervention. Adherence to vitamin D3 was monitored using drug diaries and pill counts. Participants continued to receive treatment until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or decision to discontinue treatment.

Outcome Measures

The primary end point was progression-free survival, which was defined as the time from the start of chemotherapy and vitamin D3 to first occurrence of documented disease progression or death. Progression-free survival was chosen as the primary end point because the primary objective of the trial was to evaluate the difference between high-dose and standard-dose vitamin D3 when given with chemotherapy as part of first-line therapy, and because progression-free survival has been shown to be a surrogate for overall survival.11

Secondary end points included tumor objective response rate (defined as the proportion of patients with complete or partial tumor response) and overall survival (defined as the time from the start of treatment to any cause of death). According to the protocol, all participants whose disease has progressed were to be followed up by clinic visit or telephone call every 3 months to assess survival until 36 months from the date that the last participant was randomized or death, whichever occurred earlier. Because the last patient was randomized in November 2016, the follow-up period to assess survival is expected to be completed in November 2019. Another secondary end point was change in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels measured at baseline, at the time of first restaging (after cycle 4 at approximately 8 weeks), at the time of second restaging (after cycle 8 at approximately 16 weeks), and at the time of treatment discontinuation.

Patients who discontinued treatment to pursue potentially curative resection were censored for progression-free survival at the time of surgery. Patients who had not experienced cancer progression or died were censored at their last known follow-up date. Efficacy end points were based on blinded independent radiological review of restaging scans, which were obtained after every 4 cycles of treatment and interpreted using the RECIST guidelines.

The incidence of adverse events also was determined as a secondary end point. Adverse events were assessed using version 4.0 of the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria. Serum calcium and other standard laboratory measures were monitored at every treatment cycle. A post hoc outcome was the disease control rate, which was defined as the proportion of patients with a complete tumor response, a partial response, or stable disease.

Measurement of Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level

Mandatory plasma samples were collected serially from all participants at 4 time points during the trial: at baseline, at the time of first restaging, at the time of the second restaging, and at the time of treatment discontinuation. To maintain the double-blind design of the trial, plasma samples were not assayed in real time, but rather banked and frozen at −80 °C.

After completion of the study, samples were sent to Heartland Assays and all of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were measured in 1 batch using a radioimmunoassay (DiaSorin Inc) as previously described.12 For quality-control purposes, there were blinded duplicates embedded with the laboratory samples that totaled 10% of the total number of samples. All laboratory personnel were blinded to treatment assignment and patient outcome. The assay was calibrated to the National Institute of Standards and Technology reference ranges. The mean coefficient of variation was 5.8%.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size calculations resulted in an initial accrual goal of 120 patients that was subsequently increased to 140 patients in January 2016 at the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring board to ensure a sufficient number of events. With 130 evaluable patients after accounting for dropout (65 patients per treatment group), a 1-sided log-rank test achieves 80% power at a 20% significance level to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.73 for cancer progression or death when comparing high-dose with standard-dose vitamin D3. One-sided testing was used because the study hypothesis was that high-dose vitamin D3 would either improve progression-free survival or not significantly change progression-free survival compared with standard-dose vitamin D3. This target HR was based on the analysis of 1043 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer enrolled in the CALGB/SWOG 80405 study that showed an adjusted HR of 0.79 for progression-free survival for those in the highest quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D level compared with those in the lowest quintile.10

Adherence to vitamin D3 was calculated as the percentage of expected capsules taken among the population of patients who received at least 1 dose of chemotherapy and vitamin D3. The primary statistical analysis was a 1-sided log-rank test comparing the progression-free survival for all patients who were randomized to high-dose vitamin D3 vs standard-dose vitamin D3 (intention-to-treat population). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate progression-free survival and overall survival times. Participants who withdrew from the study or were lost to follow-up were censored at their last known follow-up date.

Supportive analysis using Cox proportional hazards modeling was performed to determine HRs and 1-sided 95% CIs after adjustment a priori for the following prognostic covariates: age (continuous), sex (male vs female), race/ethnicity (white vs all others), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; <25 vs 25 to <30 vs ≥30), ECOG performance status (0 vs 1), and number of metastatic sites (continuous). Race/ethnicity was self-reported based on open-ended questioning and included as a covariate a priori due to known racial disparities in vitamin D status13 and colorectal cancer–related mortality.14 Patients with unknown race or ethnicity were grouped into the category of all others in the multivariable model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residuals method and no violation was detected.

Multivariable models were performed within prespecified subgroups of patients (defined by the baseline characteristics in Table 1) and the baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D level. One-sided P values for interaction were calculated using the likelihood ratio test. The tumor objective response rate was assessed in the evaluable patient population (received ≥1 dose of chemotherapy and vitamin D3 and underwent ≥1 restaging scan) as the proportion of participants with complete or partial response per the RECIST guidelines. The corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared between the treatment groups using the 2-sided Mann-Whitney test. Patients with missing plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D values were excluded from these analyses.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Vitamin D3 Group.

| Characteristic | High-Dose Vitamin D3 (n = 69) |

Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 54 (47-65) | 56 (50-64) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 41 (59) | 38 (54) |

| Female | 28 (41) | 32 (46) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| White | 52 (75) | 55 (79) |

| Black | 4 (6) | 6 (9) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1) |

| >1 race | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Othera | 11 (16) | 7 (10) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)b | 28 (7) | 27 (6) |

| ECOG performance status, No. (%)c | ||

| 0 | 29 (42) | 40 (57) |

| 1 | 40 (58) | 30 (43) |

| Primary tumor location, No. (%) | ||

| Right colon (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure) | 16 (23) | 19 (27) |

| Transverse colon | 4 (6) | 8 (11) |

| Left colon (splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid, rectosigmoid, rectum) | 49 (71) | 43 (61) |

| Primary tumor resected, No. (%) | 26 (38) | 21 (30) |

| Received prior adjuvant therapy, No. (%) | 6 (9) | 5 (7) |

| No. of metastatic sites, mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.9) |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 48.0 (7.4-335.1)d | 91.9 (5.9-333.5) |

| Microsatellite instability status, No. (%)e | ||

| High | 1 (2) | 5 (7) |

| Stable | 56 (81) | 48 (69) |

| Unknown | 12 (17) | 17 (24) |

| KRAS mutation status, No. (%) | ||

| Wild type | 40 (58) | 35 (50) |

| Mutated | 26 (38) | 28 (40) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) | 7 (10) |

| NRAS mutation status, No. (%) | ||

| Wild type | 38 (55) | 41 (59) |

| Mutated | 1 (2) | 3 (4) |

| Unknown | 30 (43) | 26 (37) |

| BRAF V600E mutation status, No. (%) | ||

| Wild type | 38 (55) | 39 (56) |

| Mutated | 5 (7) | 9 (13) |

| Unknown | 26 (38) | 22 (31) |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IQR, interquartile range.

Includes 7 who self-reported Hispanic or Latino ethnicity and 11 who reported unknown race or ethnicity.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

A performance status of 0 indicates a patient who is fully active and able to continue all predisease performance tasks without restriction. A performance status of 1 indicates a patient who is restricted during physically strenuous activity, but is ambulatory and able to perform light housework or office work.

Missing data for 1 patient.

A subset of colorectal cancers are characterized by deficient or defective DNA mismatch repair, which results in replicative errors in and altered length of microsatellites (microsatellite instability). Microsatellites are short (1-6 base pairs) repetitive DNA sequences that are interspersed throughout the genome and susceptible to replication errors caused by slippage of DNA polymerases over tandem repeats.

Post Hoc Analyses

The log-rank test was stratified by ECOG performance status post hoc due to an imbalance in this variable between the treatment groups. This stratified test was considered to be a less biased assessment of the primary end point than the unstratified log-rank test. In addition, a mixed-effects model was performed for the post hoc sensitivity analysis to evaluate the effect of multiple enrolling sites. Additional post hoc adjustment for primary tumor location in the multivariable model also was conducted. The tumor objective response rate and disease control rate were assessed in the evaluable patient population (received ≥1 dose of chemotherapy and vitamin D3 and underwent ≥1 restaging scan) and compared between treatment groups using a 1-sided χ2 test.

The threshold for statistical significance was .05 for all analyses. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary end points and the post hoc analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

The initial results of this study15 were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in June 2017 using data that were locked on April 25, 2017, which was approved by the data and safety monitoring board. The final data lock occurred on September 1, 2018. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Between March 29, 2012, and November 9, 2016, 166 patients were screened for eligibility, 140 provided consent, and 139 were randomized (Figure 1); 1 patient was found to be ineligible and therefore not randomized. Among the 139 randomized patients, 69 were assigned to high-dose vitamin D3 and 70 were assigned to standard-dose vitamin D3. As of September 1, 2018, all patients had completed treatment with chemotherapy and vitamin D3. The median follow-up time was 22.9 months (IQR, 11.8-34.5 months).

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1), with slightly more patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group. The number of cycles of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab administered between the groups was similar (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Adherence to vitamin D3 was high, with a median of 98% of expected capsules taken by patients in both treatment groups.

Primary Outcome

A total of 111 progression-free survival events occurred (49 in the high-dose vitamin D3 group and 62 in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group). The median progression-free survival (the primary end point of the study) was 13.0 months (95% CI, 10.1-14.7 months) for patients in the high-dose vitamin D3 group compared with 11.0 months (95% CI, 9.5-14.0 months) in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group (unadjusted log-rank P = .07; Figure 2). In a supporting analysis, the multivariable HR for progression-free survival or death was 0.64 (95% CI, 0-0.90; P = .02).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Progression-Free Survival by Vitamin D3 Treatment Group (N = 139).

Patients in the high-dose vitamin D3 group had a median follow-up of 21.0 months (interquartile range, 11.2-34.4 months) compared with 24.3 months (interquartile range, 14.5-34.5 months) for patients in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group. The hazard ratio was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and number of metastatic sites.

Secondary Outcomes

Among 128 evaluable patients, the secondary end point of tumor objective response rate was 58% (95% CI, 45%-70%) among patients receiving high-dose vitamin D3 vs 63% (95% CI, 50%-75%) among those receiving standard-dose vitamin D3. The secondary end point of overall survival was not yet mature at the time of analysis with only 99 deaths (45 in the high-dose vitamin D3 group and 54 in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group). However, median overall survival was not significantly different between the groups (24.3 months [95% CI, 19.0-33.2 months] for patients receiving high-dose vitamin D3 vs 24.3 months [95% CI, 20.3-32.4 months] for those receiving standard-dose vitamin D3; log-rank P = .43).

The change in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during treatment with chemotherapy and vitamin D3 was evaluated as a prespecified secondary end point. At baseline, median plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were deficient in both the high-dose vitamin D3 group (16.1 ng/mL [IQR, 10.1 to 23.0 ng/mL]) and in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group (18.7 ng/mL [IQR, 13.5 to 22.7 ng/mL]) (difference, −2.6 ng/mL [95% CI, −6.6 to 1.4 ng/mL], P = .30; Table 2). Only 9% of the total study population had sufficient levels (≥30 ng/mL) of 25-hydroxyvitamin D at baseline.

Table 2. Secondary End Point of Change in Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level Measured at 4 Time Points.

| High-Dose Vitamin D3 | Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 | Median Difference in 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level (95% CI), ng/mLa |

P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | ||||

| No. of patients | 63 | 61 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 16.1 (10.1 to 23.0) | 18.7 (13.5 to 22.7) | −2.6 (−6.6 to 1.4) | .30 |

| At first restaging (after 4 cycles) | ||||

| No. of patients | 54 | 50 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 32.0 (25.7 to 39.5) | 18.7 (16.1 to 22.5) | 12.8 (9.0 to 16.6) | <.001 |

| At second restaging (after 8 cycles) | ||||

| No. of patients | 47 | 37 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 35.2 (25.0 to 45.4) | 18.5 (16.0 to 22.6) | 16.7 (10.9 to 22.5) | <.001 |

| At treatment discontinuation | ||||

| No. of patients | 43 | 47 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 34.9 (24.9 to 44.7) | 18.7 (13.9 to 23.0) | 16.2 (9.9 to 22.4) | <.001 |

| Change from baseline to first restaging | ||||

| No. of patients | 50 | 47 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 17.6 (9.9 to 25.0) | −0.5 (−2.1 to 3.5) | 17.8 (13.3 to 22.2) | <.001 |

| Change from baseline to second restaging | ||||

| No. of patients | 46 | 34 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 17.3 (7.6 to 27.8) | −0.4 (−2.3 to 4.0) | 17.2 (11.0 to 23.3) | <.001 |

| Change from baseline to treatment discontinuation | ||||

| No. of patients | 38 | 43 | ||

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 21.2 (6.6 to 32.6) | 0.8 (−3.2 to 2.3) | 20.2 (11.4 to 29.0) | <.001 |

| Level of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, No./Total (%) | ||||

| ≥20 ng/mL | ||||

| At baseline | 15/63 (24) | 22/61 (36) | .68 | |

| At first restaging | 50/54 (93) | 20/50 (40) | <.001 | |

| At second restaging | 44/47 (94) | 15/37 (41) | <.001 | |

| At treatment discontinuation | 38/43 (88) | 22/47 (47) | <.001 | |

| ≥30 ng/mL | ||||

| At baseline | 7/63 (11) | 4/61 (7) | .53 | |

| At first restaging | 34/54 (63) | 0 | <.001 | |

| At second restaging | 31/47 (66) | 1/37 (3) | <.001 | |

| At treatment discontinuation | 24/43 (56) | 2/47 (4) | <.001 | |

| ≥40 ng/mL | ||||

| At baseline | 0 | 1/61 (2) | .49 | |

| At first restaging | 13/54 (24) | 0 | <.001 | |

| At second restaging | 15/47 (32) | 0 | <.001 | |

| At treatment discontinuation | 17/43 (40) | 0 | <.001 | |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

SI conversion factor: To convert 25-hydroxyvitamin D to nmol/L, multiply by 2.496.

The median difference in 25-hydroxyvitamin D level was estimated using PROC QUANTREG in SAS. PROC QUANTREG uses the default (simplex) algorithm to estimate the median difference and a combination of the resampling and rank methods to estimate the 95% CIs.

Two-sided and calculated using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables.

Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels increased into the sufficient range at the time of the first restaging among patients in the high-dose vitamin D3 group (median level, 32.0 ng/mL [IQR, 25.7-39.5 ng/mL]), whereas patients in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group had no substantial change in their 25-hydroxyvitamin D level (median level, 18.7 ng/mL [IQR, 16.1-22.5 ng/mL]) (difference, 12.8 ng/mL [95% CI, 9.0-16.6 ng/mL]; P < .001).

Similarly, at the time of the second restaging, patients taking high-dose vitamin D3 had a median 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 35.2 ng/mL (IQR, 25.0-45.4 ng/mL), whereas those taking standard-dose vitamin D3 had a median 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 18.5 ng/mL (IQR, 16.0-22.6 ng/mL) (difference, 16.7 ng/mL [95% CI, 10.9-22.5 ng/mL]; P < .001).

At treatment discontinuation, patients in the high-dose vitamin D3 group maintained vitamin D sufficiency and had a median 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 34.8 ng/mL (IQR, 24.9-44.7 ng/mL), whereas those in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group were still deficient in vitamin D and had a median 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 18.7 ng/mL (IQR, 13.9-23.0 ng/mL) (difference, 16.2 ng/mL [95% CI, 9.9-22.4 ng/mL]; P < .001).

The change in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels from baseline to either the time of first or second restaging appears in eFigure in Supplement 2 (with the most recent value available plotted) along with cancer status at the time of follow-up among patients who had both a baseline and at least 1 follow-up 25-hydroxyvitamin D value (n = 109).

Subgroup Analyses

The effects of high-dose vitamin D3 in prespecified, clinically relevant subgroups of patients appears in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. There were no statistically significant differences in the effects of high-dose vitamin D3 between patients with baseline plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL or less vs levels greater than 20 ng/mL (P = .40 for interaction). The effect of high-dose vitamin D3 on progression-free survival appeared to be greater among patients with a lower body mass index (P = .04 for interaction), more metastatic sites (P = .02 for interaction), and KRAS wild-type tumors (P = .04 for interaction). There was insufficient power to test for effect modification by microsatellite instability or NRAS mutation status.

Post Hoc Analyses

Comparison of progression-free survival between the high-dose and standard-dose vitamin D3 groups using a log-rank test stratified by ECOG performance status was statistically significant (P = .03). A sensitivity analysis using a mixed-effects model to evaluate the effect of multiple participating enrollment sites on the relationship between vitamin D3 supplementation and progression-free survival did not change the primary results (adjusted HR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0-0.90]; P = .02). Further adjustment for primary tumor location also did not change the effect of high-dose vitamin D3 on progression-free survival (HR, 0.66 [95% CI, 0-0.94]; P = .02).

Among 128 evaluable patients, the secondary end point of tumor objective response rate was compared between the high-dose and standard-dose vitamin D3 groups and was found to be similar (difference, −5% [95% CI, −20% to 100%]; P = .27). The end point of disease control rate was 100% for the high-dose vitamin D3 group vs 95% for the standard-dose vitamin D3 group (difference, 4.8% [95% CI, 0% to 100%]; P = .06).

Adverse Events

Adverse events considered grade 3 and higher that were reported by at least 5% of the evaluable patients appear in Table 3. The most common adverse events were neutropenia (24 patients [35%] in the high-dose vitamin D3 group vs 21 patients [31%] in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group) and hypertension (9 patients [13%] vs 11 patients [16%], respectively). There were fewer episodes of diarrhea reported in the high-dose vitamin D3 group (1 patient [1%]) than in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group (8 events [12%]).

Table 3. Grade 3 and Higher Adverse Events.

| Adverse Eventa | Reported by ≥5% of Evaluable Patients, No. (%)b |

|

|---|---|---|

| High-Dose Vitamin D3 (n = 68) |

Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 (n = 67) |

|

| Neutropenia | 24 (35) | 21 (31) |

| Hypertension | 9 (13) | 11 (16) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 6 (9) | 5 (7) |

| Fatigue | 3 (4) | 6 (9) |

| Thromboembolic event | 5 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1) | 8 (12) |

| Vomiting | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Anemia | 3 (4) | 5 (7) |

| Hyperglycemia | 5 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Hypokalemia | 5 (7) | 2 (3) |

| Leukopenia | 4 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (6) | 3 (4) |

The maximum grade per patient per event was used. The adverse events are listed in order of most frequent to least frequent in the overall study population.

There were 135 patients who took at least 1 dose of vitamin D3 or chemotherapy and were evaluable for adverse event assessment.

The only adverse events that were reported as possibly related to vitamin D3 were hyperphosphatemia (1 patient in high-dose vitamin D3 group) and kidney stones (1 patient in the standard-dose vitamin D3 group). Hypercalcemia was not observed in any of the patients enrolled in the study.

Two patients died while receiving chemotherapy and vitamin D3 but neither death was related to vitamin D3. Specifically, 1 of the patients who was assigned to standard-dose vitamin D3 was hospitalized on day 1 during cycle 1 after receiving mFOLFOX chemotherapy (no bevacizumab or vitamin D3 had been administered) and subsequently died due to gastrointestinal bleeding related to underlying cancer. The second patient was hospitalized for sepsis after receiving 3 cycles of mFOLFOX, bevacizumab, and high-dose vitamin D3 that was thought to be related to chemotherapy treatment.

Discussion

In this phase 2 clinical trial involving 139 patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer, assignment to high-dose vitamin D3 plus chemotherapy compared with patients assigned to standard-dose vitamin D3 plus chemotherapy resulted in a difference in median progression-free survival that was not statistically significant. However, the supportive Cox proportional hazards analysis resulted in a significantly improved HR.

The tumor objective response rate and overall survival rate were not statistically different between the groups. Median plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels increased into the sufficient range with high-dose vitamin D3, but remained unchanged with standard-dose vitamin D3. To our knowledge, this study is the first completed randomized clinical trial of vitamin D3 supplementation for the treatment of advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer, and the findings warrant further evaluation in a phase 3 randomized trial.

This trial builds on previous prospective observational studies that linked higher vitamin D status to improved survival among patients with all stages of colorectal cancer.7,8,9 In an analysis of 304 patients with colorectal cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, subgroup analyses suggested that the benefit of a higher plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D level on overall survival may be greater among patients with stage III or IV disease vs stage I or II.7

A subsequent follow-up study among 515 patients with stage IV colorectal cancer enrolled in the phase 3 North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) 9741 trial found a significant relationship between higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and improved survival among patients receiving FOLFOX.16 Because the sample size in NCCTG 9741 was relatively small, a larger analysis of 1043 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer nested within CALGB/SWOG 80405 was conducted that confirmed an association between higher plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and improved progression-free survival and overall survival.10

More recently, the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL) further corroborated the protective effect of vitamin D on cancer mortality, reporting lower rates of death caused by cancer among participants randomized to vitamin D3 vs placebo (HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.52-1.00]).17

Although the most well-studied function of vitamin D is control of calcium and phosphate metabolism for skeletal health, research has shown that 1α-hydroxylase (which converts 25-hydroxyvitamin D into active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) and the vitamin D receptor are present in most cells of the body,18,19 including colorectal cancer cells.20,21 The presence of these factors in colorectal cancer cells suggests that 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 can be synthesized locally within the tumor and microenvironment to yield high concentrations for autocrine and paracrine effects. Vitamin D was shown to induce differentiation and inhibit growth in colorectal cancer cell lines and xenograft models,22,23 reduce the size of intestinal adenomas in ApcMin mice,24 and promote sensitivity to 5-FU.25

Several potential mechanisms of action may explain the activity of vitamin D in colorectal cancer. Vitamin D induces apoptosis,1 counteracts aberrant WNT-β catenin signaling (a critical pathway in the etiology of colorectal cancer),26 and has broad anti-inflammatory effects via downregulation of nuclear factor-κB and inhibition of cyclooxygenase expression.27 Moreover, because the vitamin D receptor and the CYP27B1 gene were expressed in all immune cells, the availability of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the microenvironment for local conversion into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 may also potentially influence the balance between regulatory and inflammatory T-cell responses.

In the current study, the hypothesis-generating finding that high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation was associated with fewer grade 3 and higher diarrhea events is consistent with preclinical evidence of vitamin D’s role in maintenance of gut mucosal barrier integrity. In vitro experiments showed that vitamin D protected against the disruption of intercellular tight junctions induced by dextran sodium sulfate that can lead to increased permeability and susceptibility to colonic injury.28 Vitamin D receptor knockout mice also developed chronic low-grade intestinal inflammation and had more severe colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate.29,30 The potential benefit of high-dose vitamin D3 on chemotherapy-induced toxicity warrants further study.

In the exploratory subgroup analyses, high-dose vitamin D3 appeared to be less effective among obese patients, possibly reflecting the sequestration of vitamin D in fat, leading to decreased bioavailability.31 This is similar to the findings from VITAL that showed a decreased incidence of cancer with vitamin D compared with placebo in participants with a lower vs a higher body mass index (P = .002 for interaction).17 Patients with KRAS-mutated tumors in the current study also seemed to derive less benefit from high-dose vitamin D3. This finding is consistent with laboratory evidence of vitamin D receptor downregulation in cell lines harboring KRAS mutations,32 and demonstration of resistance to growth inhibition by 1,25-dihyroxycholecalciferol (the active metabolite of vitamin D) in a RAS-transformed cell line of human keratinocytes.33,34 These interactions suggest that certain subsets of patients may need even higher doses of vitamin D3 for antitumor activity.

The strengths of this study include the randomized, double-blind design of the trial, recruitment of patients from both academic and community-based sites, and the high adherence to vitamin D3 among the participants. Although vitamin D3 is easily accessible over the counter, there was no evidence of contamination of the control group as evidenced by the lack of change in 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels among patients receiving standard-dose vitamin D3 throughout the course of the trial.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and there was a lack of diversity in race and geographical residence among the participants in the study, limiting the ability to evaluate the effect of high-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in specific subpopulations.

Second, this trial was not powered or designed to detect an overall survival benefit, which would require a much larger sample size and study duration.

Third, because vitamin D3 supplementation was stopped at the time of first cancer progression with no further monitoring of supplement use or plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and because data on subsequent therapies was not routinely collected, it is not known how the treatment decisions made after patients exited the study affected overall survival outcomes.

Conclusions

Among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, addition of high-dose vitamin D3, vs standard-dose vitamin D3, to standard chemotherapy resulted in a difference in median progression-free survival that was not statistically significant, but with a significantly improved supportive hazard ratio. These findings warrant further evaluation in a larger multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Summary of chemotherapy and vitamin D3 treatment administration for patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer who were enrolled on a randomized phase 2 trial of high-dose vs. standard-dose vitamin D3 and who received at least one dose of chemotherapy or vitamin D3

eTable 2. Multivariable hazard ratios (HR) of progression or death comparing high-dose to standard-dose vitamin D3 in subgroups of patients defined by prespecified clinical and pathologic characteristics

eFigure. Hybrid parallel line plot of change in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels (ng/mL) from baseline to either first or second restaging among patients randomized to high dose (H, orange) vs. standard-dose (S, blue) vitamin D3 who have both a baseline and at least one on-treatment plasma 25(OH)D assessment (n=109)

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Díaz GD, Paraskeva C, Thomas MG, Binderup L, Hague A. Apoptosis is induced by the active metabolite of vitamin D3 and its analogue EB1089 in colorectal adenoma and carcinoma cells: possible implications for prevention and therapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60(8):2304-2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeong Y, Swami S, Krishnan AV, et al. Inhibition of mouse breast tumor-initiating cells by calcitriol and dietary vitamin D. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(8):1951-1961. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scaglione-Sewell BA, Bissonnette M, Skarosi S, Abraham C, Brasitus TA. A vitamin D3 analog induces a G1-phase arrest in CaCo-2 cells by inhibiting cdk2 and cdk6: roles of cyclin E, p21Waf1, and p27Kip1. Endocrinology. 2000;141(11):3931-3939. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iseki K, Tatsuta M, Uehara H, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis as a mechanism for inhibition by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of colon carcinogenesis induced by azoxymethane in Wistar rats. Int J Cancer. 1999;81(5):730-733. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans SR, Shchepotin EI, Young H, Rochon J, Uskokovic M, Shchepotin IB. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthetic analogs inhibit spontaneous metastases in a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon carcinogenesis model. Int J Oncol. 2000;16(6):1249-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, Yang J, Liu Z, Qin H. Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(28):3775-3782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):2984-2991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mezawa H, Sugiura T, Watanabe M, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and survival of patients with colorectal cancer: post-hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:347. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zgaga L, Theodoratou E, Farrington SM, et al. Plasma vitamin D concentration influences survival outcome after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(23):2430-2439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng K, Venook AP, Sato K, et al. Vitamin D status and survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results from CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; May 30, 2015; Chicago, IL. Abstract 3503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicero G, De Luca R, Dieli F. Progression-free survival as a surrogate endpoint of overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3059-3063. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S151276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollis BW. Quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by radioimmunoassay using radioiodinated tracers. Methods Enzymol. 1997;282:174-186. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)82106-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, et al. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):187-192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiscella K, Winters P, Tancredi D, Hendren S, Franks P. Racial disparity in death from colorectal cancer: does vitamin D deficiency contribute? Cancer. 2011;117(5):1061-1069. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng K, Nimeiri HS, McCleary NJ, et al. SUNSHINE: Randomized double-blind phase II trial of vitamin D supplementation in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15S):3506A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng K, Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: findings from Intergroup trial N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1599-1606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. ; VITAL Research Group . Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):33-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Zhu J, DeLuca HF. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523(1):123-133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, et al. Extrarenal expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3)-1 alpha-hydroxylase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):888-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meggouh F, Lointier P, Saez S. Sex steroid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in human colorectal adenocarcinoma and normal mucosa. Cancer Res. 1991;51(4):1227-1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bises G, Kállay E, Weiland T, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase expression in normal and malignant human colon. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(7):985-989. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4B6271.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisman JA, Barkla DH, Tutton PJ. Suppression of in vivo growth of human cancer solid tumor xenografts by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 1987;47(1):21-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shabahang M, Buras RR, Davoodi F, et al. Growth inhibition of HT-29 human colon cancer cells by analogues of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 1994;54(15):4057-4064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huerta S, Irwin RW, Heber D, et al. 1alpha,25-(OH)(2)-D(3) and its synthetic analogue decrease tumor load in the Apc(min) Mouse. Cancer Res. 2002;62(3):741-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Hu X, Chakrabarty S. Vitamin D mediates its action in human colon carcinoma cells in a calcium-sensing receptor-dependent manner: downregulates malignant cell behavior and the expression of thymidylate synthase and survivin and promotes cellular sensitivity to 5-FU. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(3):631-639. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman D, Krishnan AV, Swami S, Giovannucci E, Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(5):342-357. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathieu C, Adorini L. The coming of age of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) analogs as immunomodulatory agents. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(4):174-179. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02294-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao H, Zhang H, Wu H, et al. Protective role of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 in the mucosal injury and epithelial barrier disruption in DSS-induced acute colitis in mice. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor are critical for control of the innate immune response to colonic injury. BMC Immunol. 2007;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(1):G208-G216. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(3):690-693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi X, Tang J, Pramanik R, et al. p38 MAPK activation selectively induces cell death in K-ras-mutated human colon cancer cells through regulation of vitamin D receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(21):22138-22144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313964200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon C, Sebag M, White JH, Rhim J, Kremer R. Disruption of vitamin D receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimer formation following ras transformation of human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(28):17573-17578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon C, Kremer R, White JH, Rhim JS. Vitamin D resistance in RAS-transformed keratinocytes: mechanism and reversal strategies. Radiat Res. 2001;155(1 pt 2):156-162. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0156:VDRIRT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Summary of chemotherapy and vitamin D3 treatment administration for patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer who were enrolled on a randomized phase 2 trial of high-dose vs. standard-dose vitamin D3 and who received at least one dose of chemotherapy or vitamin D3

eTable 2. Multivariable hazard ratios (HR) of progression or death comparing high-dose to standard-dose vitamin D3 in subgroups of patients defined by prespecified clinical and pathologic characteristics

eFigure. Hybrid parallel line plot of change in plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels (ng/mL) from baseline to either first or second restaging among patients randomized to high dose (H, orange) vs. standard-dose (S, blue) vitamin D3 who have both a baseline and at least one on-treatment plasma 25(OH)D assessment (n=109)

Data sharing statement