This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial determines the association of thrombectomy among patients by age, symptom severity, time to randomization, arterial occlusive lesion location, and imaging modality.

Key Points

Question

Is the benefit of endovascular stroke therapy in the extended (6 to 16 hours) time window universal or limited to subgroups?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial, endovascular therapy resulted in in better functional outcome among a broad patient population. Treatment effect was not significantly modified by age (range, 23-90 years), symptom severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale range, 6-38), time to randomization (range, 6-16 hours), arterial occlusive lesion location (internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery), or imaging modality (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging).

Meaning

Endovascular therapy should not be withheld because of old age, mild symptoms, or late presentation in patients with large-vessel strokes and salvageable tissue on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Abstract

Importance

The DEFUSE 3 randomized clinical trial previously demonstrated benefit of endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke in the 6- to 16-hour time window. For treatment recommendations, it is important to know if the treatment benefit was universal.

Objective

To determine the outcomes among patients who may have a reduced effect of thrombectomy, including those who are older, have milder symptoms, or present late.

Design, Setting, and Participants

DEFUSE 3 was a randomized, open-label, blinded end point trial conducted from May 2016 to May 2017. This multicenter study included 38 sites in the United States. Of 296 patients who were enrolled in DEFUSE 3, 182 patients met all inclusion criteria and were randomized and included in the intention-to-treat analysis, which was conducted in August 2017. These patients had acute ischemic strokes due to an occlusion of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery and evidence of salvageable tissue on perfusion computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The study was stopped early for efficacy.

Interventions

Endovascular thrombectomy plus medical management vs medical management alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Functional outcome at day 90, assessed on the modified Rankin Scale. Multivariate ordinal logistic regression was used to calculate the adjusted proportional association between endovascular treatment and clinical outcome (shift in the distribution of modified Rankin Scale scores expressed as a common odds ratio) among patients of different ages, baseline stroke severities, onset-to-treatment times, locations of the arterial occlusion, and imaging modalities used to document the presence of salvageable tissue (computed tomography vs magnetic resonance imaging).

Results

This study included 182 patients (median [interquartile range] age, 70 [59-80] years; median [interquartile range] National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, 16 [11-21], and 92 women [51%]). In the overall cohort, independent predictors of better functional outcome were younger age, lower baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, and lower serum glucose level. The common odds ratio for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy, adjusted for these variables, was 3.1 (95% CI, 1.8-5.4). There was no significant interaction between this treatment effect and age (P = .93), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (P = .87), time to randomization (P = .56), imaging modality (P = .49), or location of the arterial occlusion (P = .54).

Conclusions and Relevance

Endovascular thrombectomy, initiated up to 16 hours after last known well time in patients with salvageable tissue on perfusion imaging, benefits patients with a broad range of clinical features. Owing to the small sample size of this study, a pooled analysis of late time window endovascular stroke trials is needed to confirm these results.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02586415

Introduction

Multiple randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that endovascular thrombectomy is effective for the treatment of ischemic stroke if treatment is initiated within 6 hours of symptom onset. Recently, 2 randomized clinical trials, DAWN1 (DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo) and DEFUSE 32 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke), demonstrated that the time window for thrombectomy can be substantially extended in patients selected on the basis of advanced neuroimaging techniques. The trials led to a revision of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Guidelines for stroke therapy: thrombectomy up to 16 hours after onset received a level 1A recommendation and thrombectomy in the 16- to 24-hour time window received a level 2B recommendation.3

In DEFUSE 3,2 patients who were likely to have salvageable ischemic brain tissue identified on perfusion imaging were randomized to receive endovascular therapy vs standard medical therapy 6 hours to 16 hours after they were last known to have been well. Compared with the medical therapy group, patients in the endovascular therapy group had a favorable shift in the distribution of functional outcomes at 90 days (P < .001), a higher percentage of functional independence (44.6% vs 16.7%, P < .001), and a lower 90-day mortality rate (14% vs 26%, P = .05). The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was similar between the 2 groups (7% and 4%, respectively, P = .75).2

As these findings are translated into clinical practice, a fundamental question is whether the benefits of thrombectomy apply to diverse patient subgroups, including very elderly persons, patients with mild symptoms, and patients who present toward the end of the 16-hour time window. Furthermore, there is uncertainty regarding whether magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) perfusion is the optimal imaging modality for evaluation of late-window patients and whether both patients with middle cerebral artery (MCA) and internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion have similar treatment benefits. The goal of this study is to examine if the benefit of thrombectomy is uniform among diverse patient subgroups.

Methods

The DEFUSE 3 study was a prospective open-label randomized clinical trial of endovascular therapy plus medical management vs medical management alone for patients presenting in the 6- to 16-hour time window with imaging evidence on CT or MRI of a large vessel occlusion and salvageable tissue. The study was approved by the StrokeNet Central institutional review board at the University of Cincinnati. All patients or their proxy signed informed consent. Details of the study protocol have been published previously4 and are available in Supplement 1.

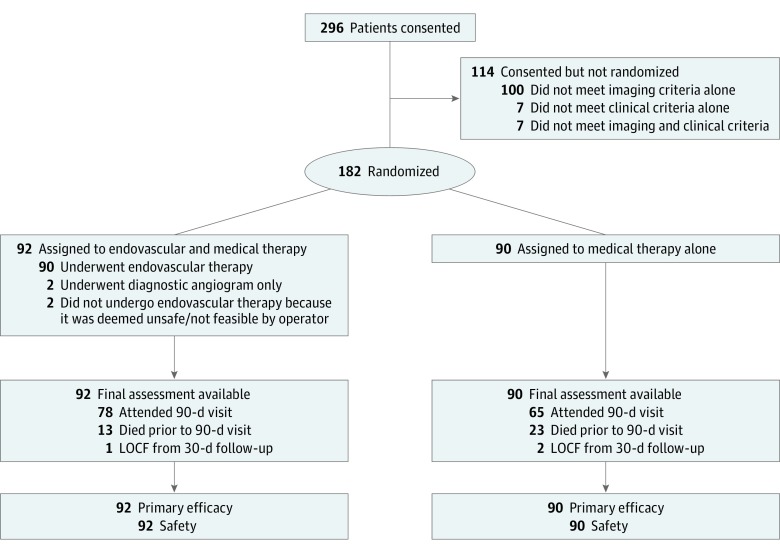

Here we report the results of prespecified analyses that assess the association of endovascular therapy in subgroups based on site of arterial occlusive lesion (ICA vs MCA) and imaging modality used for patient selection (MRI vs CT). We also report post hoc analyses investigating the association of endovascular therapy as a function of onset-to-randomization time, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and age. All patients who were randomized in the DEFUSE 3 study were included in the analyses (N = 182), except for the analysis regarding onset-to-randomization time, which was limited to patients for whom the exact time of symptom onset was known (n = 66) (Figure 1). Location of the arterial occlusive lesion (ICA vs MCA) was determined by the DEFUSE 3 radiology core laboratory, based on a review of the baseline CT or MRI angiogram. The imaging modality (CT or MRI) used to qualify a patient for the DEFUSE 3 study was defined as the imaging modality that demonstrated presence of a substantial volume of salvageable tissue (an ischemic core less than 70 mL, a relative volume of potentially reversible ischemia of 80% or more, and an absolute volume of potentially reversible ischemia of 15 mL or more).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

LOCF indicates last observation carried forward.

The primary outcome for the analyses was 90-day functional outcome assessed on the ordinal modified Rankin Scale (mRS). The secondary outcome was the percentage of patients who were functionally independent, defined as an mRS score of 2 or less at day 90. For 3 patients who were lost to follow-up at day 90, the mRS score at day 30 was used as their primary outcome under the last observation carried forward principle.

We first constructed proportional odds models to identify independent predictors of outcome. Functional outcome at day 90 was the dependent variable in each model. Independent variables tested in univariable analyses included those that have previously been shown to affect outcome (treatment assignment, time to randomization, age, NIHSS score, sex, glucose, systolic blood pressure, lesion volume). Variables significant at α < .10 in univariate analyses were entered into a multivariable model and were retained in the multivariable model if they were significant at α < .05. This served as our base model for subsequent analyses of treatment effect modification. To determine how the treatment effect changes with age, NIHSS score, time, arterial occlusive lesion, and imaging modality, we created 5 separate models; these were created by adding the variable of interest and its interaction term with treatment as independent variables to the base model. Treatment effects were expressed as adjusted common odds ratios (ORs) for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy. When the test for proportionality of the ORs was rejected, we used logistic regression models with functional independence (mRS 0-2) as the dependent variable instead of ordinal logistic regression and expressed results as adjusted ORs for functional independence with endovascular therapy. All tests were 2 sided, and analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

DEFUSE 3 randomized 182 patients, 92 of whom were assigned to endovascular therapy. All 182 patients were included in the analyses for this study. Univariable and multivariable predictors of functional outcome on the full range of mRS scores are presented in the Table. Significant covariates of better functional outcome in multivariable analysis were younger age, lower baseline NIHSS score, and lower serum glucose level. All analyses reported below were adjusted for these covariates.

Table. Predictors of 90-d Functional Outcome.

| Variable | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Treatment | 2.77 (1.63-4.70) | <.001 | 3.12 (1.81-5.38) | <.001 |

| Age, y | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | <.001 | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | <.001 |

| NIHSS score | 0.86 (0.82-0.90) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.84-0.92) | <.001 |

| Glucose, per 10 mg/dL | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | .04 | 0.94 (0.90-0.99) | .02 |

| Onset-to-randomization time | 0.94 (0.85-1.05) | .26 | NA | NA |

| Core volume, per 10 mL | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) | .17 | NA | NA |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.59 (0.95-2.66) | .08 | NA | NA |

| SBP, per 10 mm Hg | 1.02 (0.90-1.15) | .76 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OR, odds ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

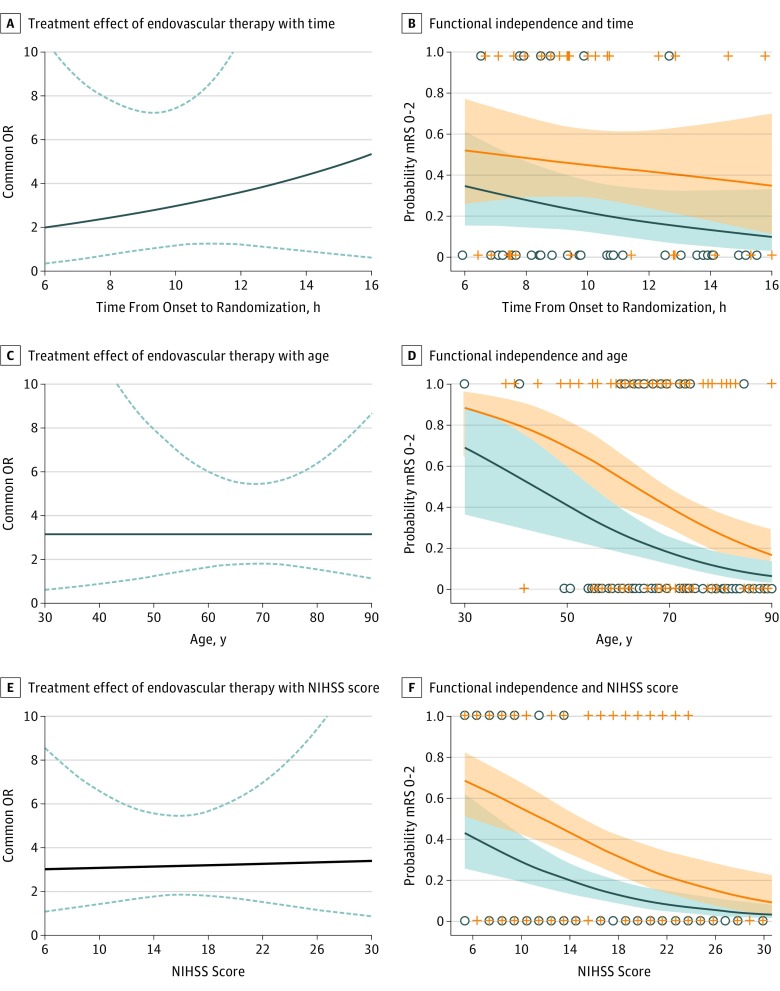

The common OR for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy, adjusted for age, NIHSS score, and serum glucose was 3.1 (95% CI, 1.8-5.4). There was no interaction between treatment and (A) time to randomization (common OR for improved functional outcome with each hour of longer time to randomization, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.67-1.06 in medical group vs 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73-1.17 in endovascular group; P for interaction = .56; range 6-16 hours), (B) age (common OR for improved functional outcome with each year of older age, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98 in medical group vs 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98 in endovascular group; P for interaction = .93; age range, 23-90 years), or (C) baseline stroke severity at time of randomization (common OR for improved functional outcome with each point of higher NIHSS score, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82-0.94 in medical group vs 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83-0.94 in endovascular group; P for interaction = .87; NIHSS score range 6-38) (Figure 2). The probability of being functionally independent (mRS 0-2) at day 90, the secondary study end point, declined with older age and higher NIHSS score in the endovascular and medical treatment arms. A similar pattern of declining probabilities in both treatment arms was observed for other dichotomous end points of the mRS (eFigures 1 to 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Endovascular Treatment Effect and Probability of Functional Independence.

The 3 graphs on the left show the treatment effect of endovascular therapy, expressed as the common odds ratio (OR) for improved functional outcome (solid blue line) and its 95% CI (dashed blue lines) expressed as a function of onset-to-randomization time (A), age (C), and baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score (E). The treatment effect did not change with any of these baseline variables. The 3 graphs on the right show the probability and 95% CI of functional independence at 90 days, separately for patients in the endovascular treatment arm (orange lines and shading) and the medical control arm (blue lines and shading). The probability of functional independence was not associated with onset-to-randomization time (B), but declined in both treatment arms with older age (D) and higher NIHSS score (F). Graphical results are for a hypothetical patient for whom covariates are fixed at the DEFUSE 3 population mean (age 69 years, NIHSS score of 16, and serum glucose of 140 mg/dL). The analysis for time from onset-to-randomization are based on the subset of patients who had a known time of stroke onset (n = 66). The other analyses are based on all patients randomized in the DEFUSE 3 trial (n = 182). mRS indicates modified Rankin Scale.

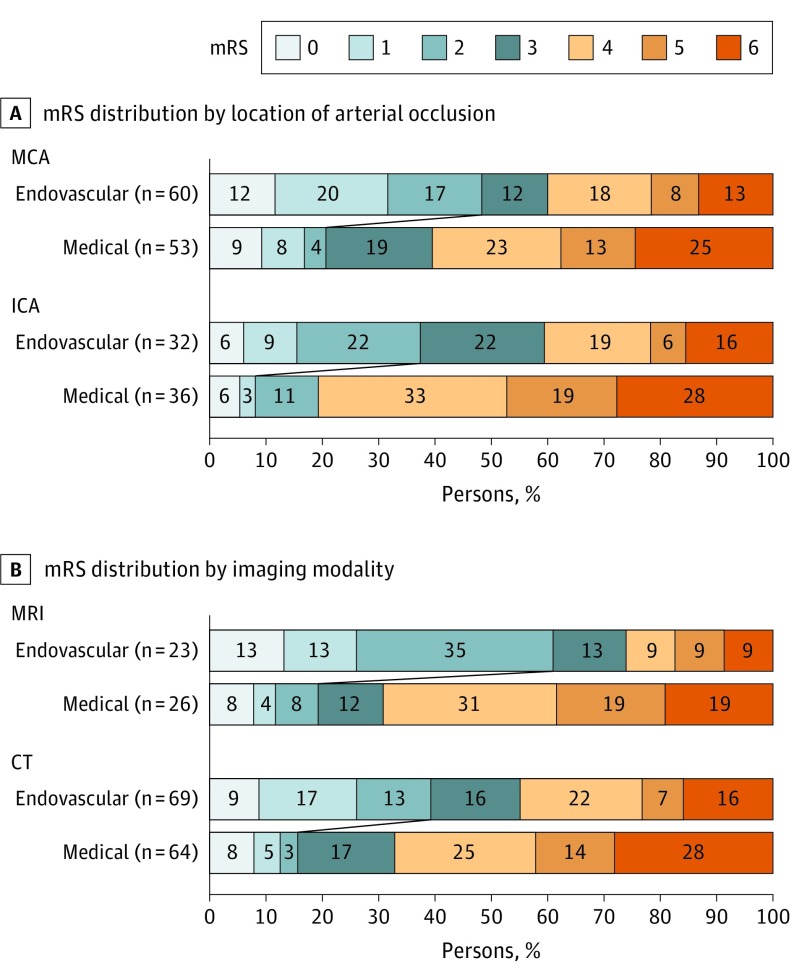

Logistic regression, with functional independence (mRS 0-2) as the dependent variable, yielded an adjusted OR for endovascular therapy of 10.6 (95% CI, 2.2-49.8) among patients with ICA occlusions and 6.0 (95% CI, 2.0-17.9) for patients with MCA occlusions (P for lesion location × treatment interaction = .54). Analysis stratified by imaging modality showed an adjusted OR of 11.9 (95% CI, 2.2-63.4) for patients selected with MRI and 6.1 (95% CI, 2.2-17.1) for patients selected with CT (P for imaging modality × treatment interaction = .49) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Distribution of Scores on the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at Day 90.

This figure shows the 90-day mRS distributions stratified by location of the arterial occlusion (A) and type of imaging modality used to select patients with salvageable tissue (B). A, Endovascular therapy was associated with improved outcomes in patients with middle cerebral artery (MCA) (odds ratio for functional independence 6.0; 95% CI, 2.0-17.9) and internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusions 10.6 (95% CI, 2.2-49.8; P for lesion location × treatment interaction = .54). B, Endovascular therapy was associated with improved outcomes in patients selected with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (odds ratio, 11.9; 95% CI, 2.2-63.4) and patients selected with computed tomography (CT) (odds ratio, 6.1; 95% CI, 2.2-17.1; P for imaging modality × treatment interaction = .49). Reported odds ratios are adjusted for age, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, and serum glucose level.

Time from onset to randomization was strongly correlated with time from onset to femoral puncture (R2 = 0.99; β = .98; P < .001) with femoral puncture occurring on average 31 minutes after randomization. (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Median (interquartile range [IQR]) times from hospital arrival to randomization were similar for CT (1:20 [0:51-2:07]) and MR (1:21 [0:50-1:49], P = .42), but the CT group had longer onset-to-randomization times (11:03 [9:16-12:53]) than MR (10:33 [8:08-11:28], P = .03) and longer hospital arrival-to-femoral puncture times (2:00 [1:21-2:48]) than MR (1:28 [1:14-2:06]; P = .02). Among patients with witnessed strokes, the CT group also had longer onset-to-randomization times (median [IQR], 10:06 [8:25-13:18]) than MR (median [IQR], 8:33 [7:30-10:46]; P = .01) The proportion of patients selected by MRI did not differ between patients who were transferred to the study site from an outside hospital (35 of 121 [29%]) and patients who were admitted directly to the study site (14 of 61 [23%], P = .48).

Discussion

This study demonstrates worse functional outcomes in patients who are older, have more severe symptoms on presentation (higher NIHSS score), and have higher serum glucose, but does not show modification of the treatment effect according to these or other baseline variables. Specifically, the proportional benefit of endovascular thrombectomy is uniform across patients with a wide range in age, symptom severity, and time from stroke onset-to-randomization and also does not differ according to the location of the arterial occlusive lesion and the imaging modality used for patient selection. While the proportional benefit (OR for improved functional outcome) is uniform, differences do exist in the absolute treatment benefit (the increase in the probability of achieving a desired functional outcome) across patients.

Our results indicate that advanced age, up to 90 years, should not be considered a contraindication to thrombectomy, provided that the patient is fully independent prior to stroke onset. Although age did not modify the treatment effect, it was a strong independent predictor of 90-day disability, which is consistent with prior studies of both tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular therapy.5,6 In DEFUSE 3, only about 20% of very elderly persons achieved functional independence following thrombectomy; however, the rate in the medical control group was nearly 0. As patients older than 90 years were excluded from DEFUSE 3, our results may not apply to nonagenarians, and because DEFUSE 3 required patients to be nondisabled prior to stoke onset, our results may also not apply to elderly patients with preexisting disability.

Consistent with prior studies of thrombolytic and endovascular therapy, baseline stroke severity was a powerful independent predictor of clinical outcome1,6 but did not modify treatment effect as demonstrated by a uniform proportional benefit of endovascular therapy for patients with NIHSS scores ranging from 6 to 38. However, this uniform proportional benefit does not imply that there also is a uniform absolute benefit. For example, patients with low NIHSS scores experienced a substantial absolute benefit in their chance of achieving functional independence but had no reduction in mortality, whereas patients with high NIHSS scores experienced a very limited benefit in functional independence but did have a reduction in mortality and severe disability (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2) A similar pattern of differences in absolute benefits with endovascular treatment was seen for patients of different ages (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Although good outcome rates were overall higher in patients with MCA occlusions, both patients with occlusions of the proximal segment of the MCA and patients with ICA occlusions benefitted from late window thrombectomy and we did not demonstrate a difference in treatment effects between groups. Similarly, patients who were selected based on CT perfusion imaging and those selected based on MRI diffusion and perfusion imaging both benefitted from endovascular therapy. These results indicate that both CT and MRI perfusion can be used for patient selection and that patients with ICA and MCA occlusions are suitable candidates for late-window endovascular therapy. A limitation of this study is that the overall sample was relatively small and we therefore had limited power to demonstrate significant differences in treatment effects between these subgroups. We were also unable to address M2 MCA segment or basilar artery occlusions as these patients were excluded from DEFUSE 3.

Among patients with known time of stroke onset, there was no attenuation of the treatment effect with increasing time between stroke onset and randomization. The lack of an association between time and treatment effect is likely explained by the study’s imaging selection criteria. All patients in DEFUSE 3 were required to have a substantial volume of salvageable tissue (ie, a target mismatch on CT or MRI perfusion imaging). Given that DEFUSE 3 was a late window trial, this requirement limited the population to patients with favorable collaterals who have slow growth of their ischemic cores. This is illustrated by the fact that the majority of patients in DEFUSE 3 had core volumes of 10 mL or less even though the median time between symptom onset and brain imaging was longer than 10 hours. Assuming that core growth is linear, this translates into a mean early core growth rate of 1 mL per hour. At these low rates, treatment delays likely do not have a substantial impact on the treatment effect. However, these findings should not be used as a justification to treat late-presenting patients with less urgency than early-presenting patients. Since the ischemic core grows with time (albeit slowly in some instances) and the penumbra thus shrinks with time,7 a patient’s chance of having a substantial volume of salvageable tissue that fulfills criteria for late-window endovascular therapy decreases if imaging is delayed.

The lack of an association between time to treatment and treatment effect in DEFUSE 3 is consistent with our findings from the DEFUSE 28 and CRISP9 studies. These studies showed no attenuation of the association of endovascular reperfusion with longer onset-to-treatment times among patients with the target mismatch profile.10,11 However, our results are in contrast with the pooled analyses of prior endovascular and thrombolytic therapy trials, which have shown an attenuation of the treatment effect with longer onset-to-treatment times.12,13 This discrepancy could be explained by a much higher proportion of patients with rapidly expanding ischemic cores in prior trials, as these trials did not require evidence of a substantial volume of salvageable tissue for inclusion. Limited power to detect an association of time in the DEFUSE 3 cohort may also have been a factor.

Limitations

While we did not detect differences in treatment effects between patient subgroups, it is possible that small differences went undetected owing to the small sample size of this study. These results therefore warrant validation in other trials of late-window endovascular therapy.

Conclusions

Endovascular therapy in the 6- to 16-hour time window among patients with evidence of salvageable tissue on brain perfusion imaging is beneficial in a broad patient population, including patients who range in age from 23 to 90 years, who have mild or severe symptoms, who are treated between 6 and 16 hours after their last known well time, who are selected by CT or MRI, and who have strokes due to either ICA or MCA occlusions.

Trial Protocol.

eFigure 1. Probability of functional outcome as a function of onset to randomization time

eFigure 2. Probability of functional outcome as a function of age

eFigure 3. Probability of functional outcome as a function of baseline NIHSS

eFigure 4. Relationship between onset-to-randomization and onset-to-femoral puncture time

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. ; DAWN Trial Investigators . Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):11-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. ; DEFUSE 3 Investigators . Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708-718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albers GW, Lansberg MG, Kemp S, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of endovascular therapy following imaging evaluation for ischemic stroke (DEFUSE 3). Int J Stroke. 2017;12(8):896-905. doi: 10.1177/1747493017701147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra NK, Ahmed N, Andersen G, et al. ; VISTA collaborators; SITS collaborators . Thrombolysis in very elderly people: controlled comparison of sits international stroke thrombolysis registry and virtual international stroke trials archive. BMJ. 2010;341:c6046. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. ; HERMES collaborators . Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723-1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lansberg MG, O’Brien MW, Tong DC, Moseley ME, Albers GW. Evolution of cerebral infarct volume assessed by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(4):613-617. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.4.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lansberg MG, Straka M, Kemp S, et al. ; DEFUSE 2 study investigators . MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):860-867. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70203-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lansberg MG, Christensen S, Kemp S, et al. ; CT Perfusion to Predict Response to Recanalization in Ischemic Stroke Project (CRISP) Investigators . Computed tomographic perfusion to predict response to recanalization in ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(6):849-856. doi: 10.1002/ana.24953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lansberg MG, Cereda CW, Mlynash M, et al. ; Diffusion and Perfusion Imaging Evaluation for Understanding Stroke Evolution 2 (DEFUSE 2) Study Investigators . Response to endovascular reperfusion is not time-dependent in patients with salvageable tissue. Neurology. 2015;85(8):708-714. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai JP, Mlynash M, Christensen S, et al. ; CRISP Investigators . Time from imaging to endovascular reperfusion predicts outcome in acute stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(4):952-957. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saver JL, Goyal M, van der Lugt A, et al. ; HERMES Collaborators . Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1279-1288. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, et al. ; ATLANTIS Trials Investigators; ECASS Trials Investigators; NINDS rt-PA Study Group Investigators . Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):768-774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eFigure 1. Probability of functional outcome as a function of onset to randomization time

eFigure 2. Probability of functional outcome as a function of age

eFigure 3. Probability of functional outcome as a function of baseline NIHSS

eFigure 4. Relationship between onset-to-randomization and onset-to-femoral puncture time

Data Sharing Statement