Abstract

Background & Aims:

Porphyrias result from anomalies of heme biosynthetic enzymes and can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer. In mice, these diseases can be modeled by administration of a diet containing 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-d ihydrocollidine (DDC), which causes accumulation of porphyrin intermediates, resulting in hepatobiliary injury. Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been shown to be a modulatable target in models of biliary injury; thus, we investigated its role in DDC-driven injury.

Methods:

β-Catenin (Ctnnb1) knockout (KO) mice, Wnt co-receptor KO mice, and littermate controls were fed a DDC diet for 2 weeks. β-Catenin was exogenously inhibited in hepatocytes by administering β-catenin dicer-substrate RNA (DsiRNA), conjugated to a lipid nanoparticle, to mice after DDC diet and then weekly for 4 weeks. In all experiments, serum and livers were collected; livers were analyzed by histology, western blotting, and real-time PCR. Porphyrin was measured by fluorescence, quantification of polarized light images, and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Results:

DDC-fed mice lacking β-catenin or Wnt signaling haddecreased liver injury compared to controls. Exogenous mice that underwent β-catenin suppression by DsiRNA during DDC feeding also showed less injury compared to control mice receiving lipid nanoparticles. Control livers contained extensive porphyrin deposits which were largely absent in mice lacking β-catenin signaling. Notably, we identified a network of key heme biosynthesis enzymes that are suppressed in the absence of β-catenin, preventing accumulation of toxic protoporphyrins. Additionally, mice lacking β-catenin exhibited fewer protein aggregates, improved proteasomal activity, and reduced induction of autophagy, all contributing to protection from injury.

Conclusions:

β-Catenin inhibition, through its pleiotropic effects on metabolism, cell stress, and autophagy, represents a novel therapeutic approach for patients with porphyria.

Keywords: Heme biosynthesis; Porphyrin; Ductular proliferation; Biliary fibrosis; 3,5-Diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) diet

Graphical Abstract

Lay summary:

Porphyrias are disorders resulting from abnormalities in the steps that lead to heme production, which cause build-up of toxic by-products called porphyrins. Liver is commonly either a source or a target of excess porphyrins, and complications can range from minor abnormalities to liver failure. In this report, we inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling in an experimental model of porphyria, which resulted in decreased liver injury. Targeting β-catenin affected multiple components of the heme biosynthesis pathway, thus preventing build-up of porphyrin intermediates. Our study suggests that drugs inhibiting β-catenin activity could reduce the amount of porphyrin accumulation and help alleviate symptoms in patients with porphyria.

Introduction

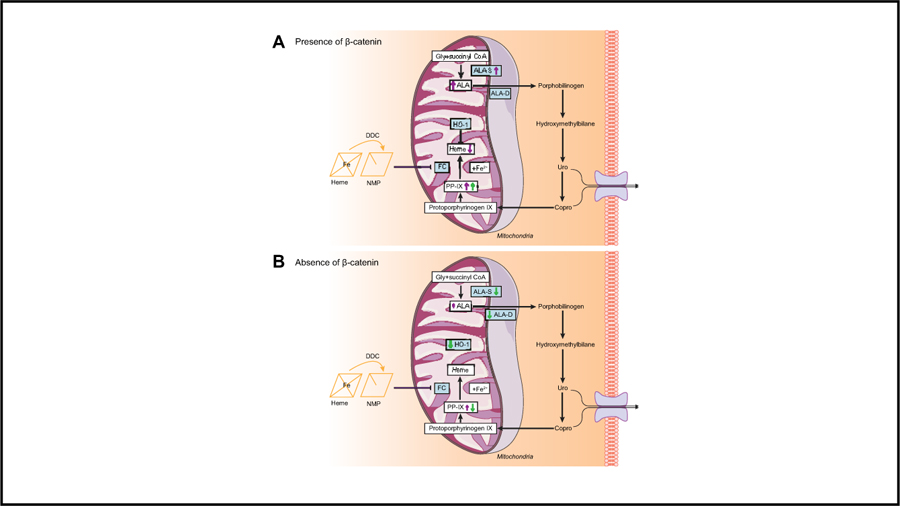

Porphyrins are precursors of heme, an essential co-factor for hemoproteins like cytochrome-P450, hemoglobin, and peroxidases. Heme biosynthesis starts in mitochondria, where ALA-synthase (ALA-S) catalyzes the combination of glycine and succinyl Co-A to form d-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). ALA leaves the mitochondria, and is sequentially converted in the cytosol to porphobilinogen, hydroxymethylbilane, uroporphyrin and then to coproporphyin, which re-enters mitochondria. In the penultimate step, protoporphyrin-IX (PP-IX) is generated, which is metallated by ferrochelatase (FC) to form the iron containing heme.1,2

3,5-Diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) has been widely used to induce hepatic porphyria and Mallory-Denk bodies in mice.3,4 DDC perturbs porphyrin metabolism at multiple steps. DDC N-methylates heme residues of some hepatic cytochrome-P450 enzymes, which subsequently demetallates and releases the tetrapyrrole moiety in the form of N-methyl protoporphyrin-IX (NMP).5 NMP is a potent inhibitor of FC and blocks conversion of PP-IX to heme.3,6 Thus, hepatic NMP accumulation causes build-up of tetrapyrrole precursors, including PP-IX. Additionally, ALA-S is under negative feedback regulation of heme.5 Inhibition of FC by NMP, and the subsequent heme-deficient state, de-represses ALA-S expres sion,7 which in turn generates more ALA that feeds forward into the heme biosynthetic pathway. DDC also induces formation of Mallory-Denk bodies (MDB), which are hepatocellular inclusions found in diseases like alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and metabolic liver diseases.8,9 Aggregates of keratin proteins K8 and K18 constitute a major component of MDB as they are early sensors of porphyrin-mediated liver injury.10 Protein aggregation hinders clearance, causing proteasomal inhibition and induction of autophagy.11,12 Because of crystallized porphyrin biliary plugs, DDC also results in ductular reaction, pericholangitis and periductal fibrosis, similar to that seen in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.13

Previously, we have shown that mice lacking β-catenin in hepatocytes and cholangiocytes (albumin-cre β-catenin knockout or KO1) had fewer A6-positive atypical ductular cells in response to DDC,14 which was not due to decreased levels of total liver bile acids.15 In the current study, we demonstrate that mice lacking Wnt/β-catenin signaling or following pharmacologic β-catenin inhibition, exhibited less hepatic injury after DDC. This was due to a novel role of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in regulating heme biosynthesis, which resulted in less porphyrin accumulation and in turn, less protein aggregates and hepatic injury.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (protocol numbers 14,013,027 and 14084364). Mice with β-catenin loxp+/+ or LRP5/6 loxp+/+ were backcrossed to Alβ-Cre+/− (all in C57BL6 background) to generate β-catenin KO (KO1) or LRP5/6 double KO (KO2) in hepatocytes and cholangiocytes as previously described.16,17 Littermates with floxed alleles but without Cre were used as respective wild-type controls (WT1, WT2). Mice at 2 months of age (approximately 25 g) were fed a diet incorporating DDC in standard chow at a concentration of 0.1% (Bioserve, Frenchtown, NJ) for 14 days and sacrificed.14 Blood was collected and serum sent to University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Clinical Chemistry lab for biochemical analysis. Liver sections were fixed in 10% formalin and processed for paraffin embedding; the remaining liver was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C.

Therapeutic intervention with β-catenin DsiRNA LNP

Two-month old male CD-1 mice were administered 3 mg/kg control or β-catenin DsiRNA formulated into a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) from Dicerna Pharmaceuticals (Watertown, MA) intravenously once weekly beginning 3 days after starting DDC diet until the time of sacrifice (day 31 after starting DDC). Male mice were used for all studies due to the sexually dimorphic effects of DDC metabolism.9 All mice were maintained in ventilated cages under 12 h light/dark cycles with access to enrichment, water and standard chow diet ad libitum.

For further details regarding the materials used, please refer to the CTAT table and supplementary information.

Results

Loss of hepatocyte Wnt/β-catenin signaling results in reduced injury after 14 days of DDC

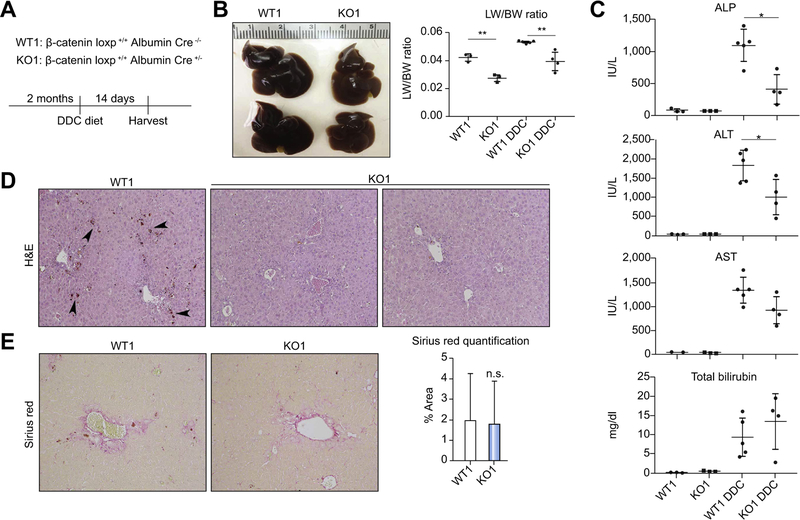

KO1, WT1, KO2 and WT2 mice were fed DDC diet for 14 days and assessed for injury (Fig. 1A, Fig. S3A). Gross examination reveals enlarged and dark brown WT livers, which is characteristic of DDC, while KO1 and KO2 livers are smaller and lighter in color (Fig. 1B, Fig. S3B). KO1 and KO2 mice also show decreased liver weight/body weight ratio (LW/BW). Notably, biliary injury is significantly decreased in KO1 and KO2; additionally, hepatic injury is decreased in KO1 compared to WT (Fig. 1C, Fig. S3C).

Fig. 1. KO1 have less injury than WT1 after DDC.

(A) Treatment regimen for WT1 and KO1 on DDC. (B) Gross liver specimens show that WT1 livers become enlarged and dark brown, while KO1 livers are smaller and lighter-colored (right panel). LW/BW ratios are lower in KO1 compared to WT1 after DDC (left panel); **p <0.01 vs. treatment-matched controls (t test). (C) Both biliary and hepatic injury are decreased in KO1 after DDC; *p <0.05 vs. WT1+DDC (t test). (D) H&E shows less porphyrin in KO1 compared to WT1 after DDC (100x). (E) Sirius red staining shows equivalent fibrosis in KO1 after DDC compared to WT1 (100x). ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; KO1, β-catenin knockout mice; LW/BW, liver weight/body weight; WT1, wild-type floxed control mice.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for glutamine synthetase (GS), a β-catenin transcriptional target, confirms absent hepatocyte β-catenin activation in both KO1 and KO2 despite continued presence of β-catenin protein in KO2, indicating deficient Wnt signaling (Fig. S1). Histology reveals KO1 and KO2 livers to have a noticeable decrease in dark brown pigmentation indicative of porphyrin accumulation compared to WT counterparts (Fig. 1D, Fig. S3D). However, fibrosis, as assessed by Sirius red, was equivalent in KO and WT for both genotypes (Fig. 1E, Fig. S3E).

We found fewer cyclin D1 positive cells in KO1 and KO2 livers by IHC, likely because of absent β-catenin signaling, which was also confirmed by western blot (Fig. S1, Fig. S2A, Fig. S4A). Ki67 IHC also showed less hepatocyte proliferation in KO1 after DDC, while cholangiocyte proliferation was unaffected despite β-catenin loss (Fig. S2A). Interestingly, Ki67-positive hepatocytes were still present in KO2 after DDC, indicating hepatocyte proliferation is independent of Wnt activation in this model (Fig. S4). IHC for EpCAM and Sox9 showed equivalent ductular response in KO and WT in both genotypes (Fig. S2B, Fig. S4B). Additionally, the ratio of phosphorylated, inactive Yap to total Yap was insignificantly decreased in KO1 and KO2 after DDC (Fig. S1B, Fig. S1D).

CD45-positive inflammatory cells were equivalent in KO1 and KO2 when compared to WT (Fig. S2C, Fig. S4C); however, there appeared to be differences in inflammatory cell subpopulations (fewer CD68+ cells in KO1, fewer F4/80+ cells in KO2), as well as fewer elastase-positive neutrophils infiltrating the periportal parenchyma. This may indicate a cell autonomous role of β-catenin in modulating the immune response after DDC.

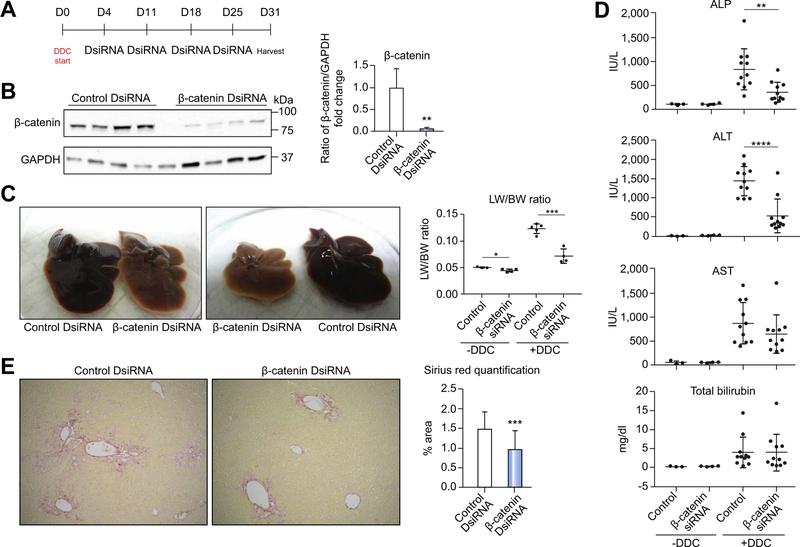

Exogenous inhibition of β-catenin using DsiRNA formulated in an LNP recapitulates the protective phenotype seen in β-catenin and LRP5/6 KO on DDC

We next suppressed β-catenin exogenously in DDC-induced injury by administering 3 mg/kg control or β-catenin DsiRNA formulated into an LNP to mice once weekly beginning 3 days after starting DDC. The CD-1 strain was used in these studies to assure rigor and reproducibility (Fig. 2A). Western blot shows successful knockdown of β-catenin protein (Fig. 2B), and that LNP preferentially targets the DsiRNA to hepatocytes (Fig. S5A). We also confirmed that DDC itself has no effect on β-catenin activation in control mice (Fig. S6). As in KO1 and KO2, livers of β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC mice were notably smaller and lighter in color, with significantly lower LW/BW ratio (Fig. 2C). Both alkaline phosphatase and alanine aminotransferase were also significantly decreased after β-catenin DsiRNA (Fig. 2D), although overall injury was reduced compared to WT1 and comparable to WT2, likely due to strain-specific differences. Fibrosis was significantly decreased, (Fig. 2E), although a-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts were evident in both control and β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers (Fig. S5B). β-Catenin DsiRNA-treated livers also showed fewer proliferating hepatocytes (Fig. S5C). CD45-positive cells were equivalent in both groups, although there appeared to be fewer F4/80-positive cells after β-catenin DsiRNA (Fig. S5D), indicating that as in KO1 and KO2, exogenous β-catenin suppression alters inflammation after DDC.

Fig. 2. Exogenous inhibition of β-catenin using DsiRNA results in decreased injury after DDC.

(A) Treatment regimen for administration of DsiRNAs after DDC. (B) Western blot confirms decreased β-catenin protein after DsiRNA treatment; **p <0.01 vs. control+DDC (t test). (C) Gross liver specimens demonstrate that control livers become enlarged and dark red, while β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers are smaller and lighter colored. LW/BW ratios are lower in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC mice; *p <0.05 and **p <0.01 vs. treatment-matched controls (t test). (D) Both biliary and hepatic injury are decreased after β-catenin DsiRNA +DDC; **p <0.01 and ****p <0.0001 vs. control+DDC (t test). (E) Sirius red staining shows a reduction in fibrosis after β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC compared to control +DDC (50x). Quantification of representative Sirius red images demonstrates significantly less fibrosis in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC; ***p <0.001 vs. control+DDC (t test). ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA; LW/BW, liver weight/body weight.

Interestingly, ductular response in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers extended from the periportal region into the parenchyma, as shown by Sox9 IHC (Fig. S5E). Despite expansion of these atypical ductules, we did not detect an increase in Notch or Yap signaling in the absence of β-catenin (Fig. S7A,7B).

Protection from injury is independent of NF-κB activation or bile acid accumulation

We previously reported β-catenin KO mice are protected from TNF-a-induced apoptosis and bile acid-induced injury through activation of NF-κB and farnesoid X receptor (FXR), respectively.15,18 We found a mild increase in NF-κB DNA binding activity after DDC, which was not further increased with β-catenin DsiRNA (Fig. S8A). Additionally, total bile acids in the liver were not significantly different between control and β-catenin DsiRNA groups after DDC (Fig. S8B). Therefore, neither increased cytoprotection nor decreased bile acid-induced injury explains the protection in the β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC group.

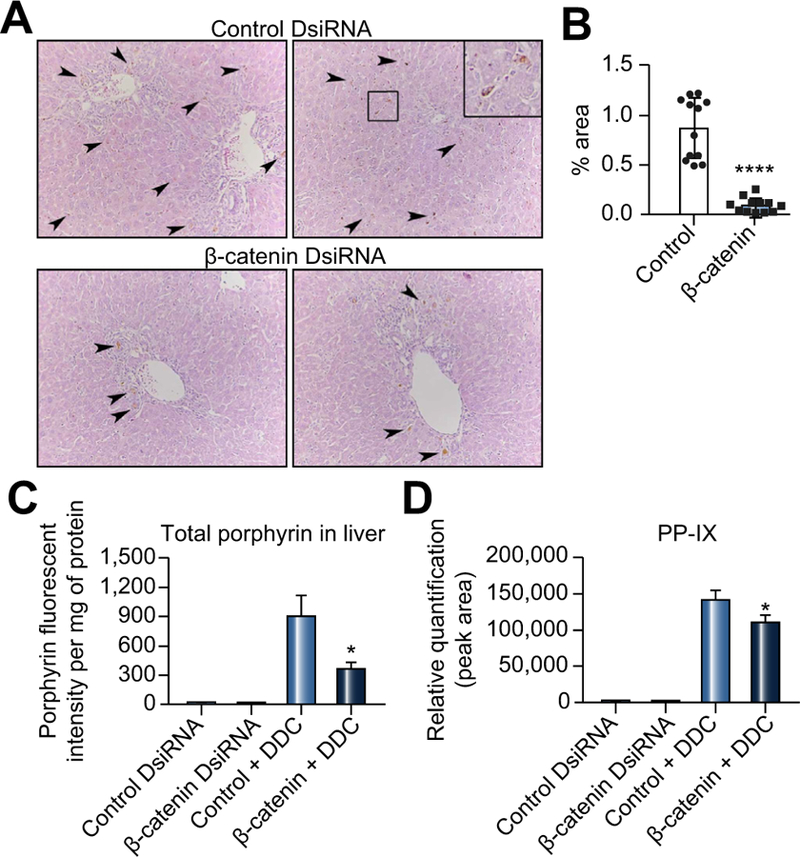

β-Catenin DsiRNA treatment reduces the amount of protoporphyrin in livers after DDC compared to control

A remarkable feature of β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers was a decrease in porphyrin accumulation, which normally gives the livers their characteristic dark brown color. Similar findings were also noted in KO1 and KO2 after DDC (Fig. 1E; Fig. S3E). Whereas in control+DDC livers porphyrin deposits were evident throughout the parenchyma and within bile ductules, in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers, only a few porphyrin plugs were evident, exclusively locating within bile ductules (Fig. 3A). Quantification of porphyrin accumulation by channel splitting of brightfield images confirms this decrease (Fig. 3B). Further-more, when total liver homogenates were assayed for porphyrin fluorescence, a 3-fold reduction in total porphyrin was evident in mice β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC compared to control+DDC (Fig. 3C). Using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) as an additional modality of measuring porphyrin content, we observed significantly reduced PP-IX levels in livers of β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC mice (Fig. 3D). Thus, inhibiting β-catenin provides protection from DDC-induced injury by decreasing porphyrin accumulation in the liver.

Fig. 3. There is decreased porphyrin accumulation in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated mice after DDC compared to DDC alone.

(A) H&E shows fewer porphyrin inclusions (arrows) in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers compared to control+DDC (200x; inset 400x). (B) There is a quantifiable decrease in porphyrin after β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC; *p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). (C) Determination of total liver porphyrins by fluorescence assay confirms less porphyrin accumulation in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers; ****p <0.0001 vs. control+DDC (t test). (D) Measurement of porphyrin intermediates by LC-MS shows decreased PP-IX in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers compared to control +DDC; *p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). n = 3 control DsiRNA, n = 3 β-catenin DsiRNA, n = 4 Control DsiRNA+DDC, n = 4 β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC. DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA; LC-MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Alterations in expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes and CAR in the absence of β-catenin do not contribute significantly to protection from DDC

Previous studies have shown an inhibitory effect of cytochrome P450 Cyp3a on DDC-induced porphyria because it oxidizes DDC to a less-toxic metabolite, thus serving as a DDC scavenger.9 Cyp3a isoforms Cyp3a1 and Cyp3a11 were significantly increased in KO1 compared to WT1 at baseline (Fig. S9A). However, expression was unchanged in mice treated with β-catenin DsiRNA at baseline before DDC (Fig. S9B); therefore, the upregulation seen in KO1 may be a compensatory response. Although β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers showed a modest but insignificant increase in Cyp3a protein expression compared to control+DDC (Fig. S9C), it is unclear if this is indicative of increased enzymatic activity or rather due to lack of Cyp degradation.5

DDC also activates the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR [encoded by Nr1i3]), which contributes to hepatic injury.19 β-catenin regulates CAR expression, and deletion of β-catenin in KO1 mice results in decreased CAR expression.20 Indeed, DsiRNA-mediated knockdown of β-catenin significantly decreases CAR expression at baseline (Fig. S9D). Interestingly, CAR expression is suppressed in control+DDC, while DDC further decreases CAR after β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC.

As increased Cyp3a and decreased CAR expression after DDC may interfere with DDC metabolism, we performed an activity assay on ferrochelatase (FC) isolated from DDC-fed mice after DsiRNA treatment. There was no measurable activity of FC in either group after DDC treatment compared to positive controls (not shown). Thus, despite alterations in pathways that regulate DDC metabolism, these are not the primary mechanisms by which β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC mice evade profound hepatic injury.

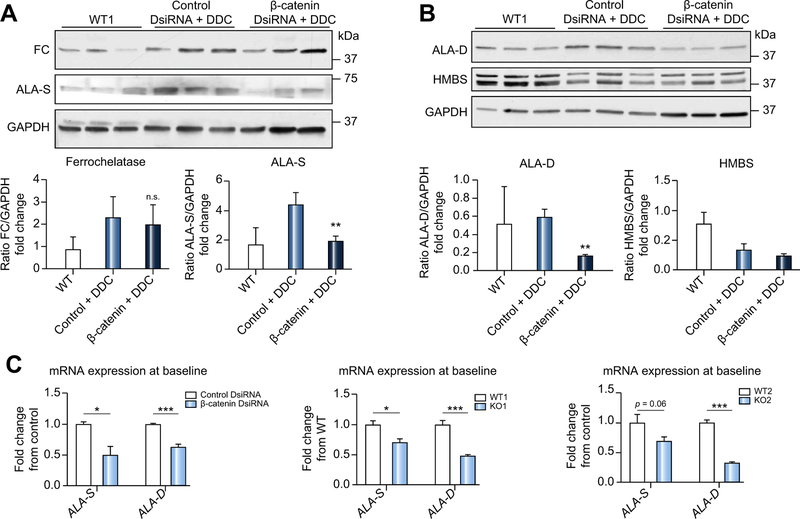

Decreased porphyrin accumulation after β-catenin DsiRNA treatment is a result of decreased expression of heme biosynthesis enzymes

Hepatic porphyrin accumulation after DDC is a result of incomplete heme biosynthesis resulting in build-up of porphyrin intermediates. We next examined the status of this pathway in β-catenin-inhibited animals. There was a marked decrease in ALA-S protein, the rate limiting enzyme in heme biosynthesis21 in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC, in contrast to control+DDC, which showed greater ALA-S than WT baseline samples (Fig. 4A). Protein levels of FC were unchanged after either DDC or administration of either DsiRNA (Fig. 4A). Additionally, levels of hydroxymethylbilane synthase, which catalyzes the synthesis of hydroxymethylbilane22 were unchanged, while d-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALA-D), which synthesizes porphobilinogen, was decreased in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Decreased porphyrin accumulation in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers is due to alterations in heme biosynthesis pathway enzymes.

(A) Western blotting shows equivalent FC protein expression in control and β-catenin DsiRNA livers after DDC, but decreased ALA-S after β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC; **p <0.01 vs. control+DDC (t test). (B) ALA-D is decreased in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers; **p <0.01 vs. control+DDC (t test). (C) Expression of ALA-S and ALA-D is significantly decreased after β-catenin DsiRNA at baseline, as well as in KO1 at baseline. ALA-D is suppressed in KO2 compared to controls at baseline, while ALA-S is insignificantly decreased. Left panel: *p <0.05 and ***p <0.001 vs. control+DDC; middle panel: *p <0.05 and ***p <0.001 vs. WT1; right panel: ***p <0.001 vs. WT2 (t test). n ≥ 3 mice per group. DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA; KO1, β-catenin knockout mice; KO2, LRP5/6 double knockout mice; WT1, wild-type floxed control mice; WT2, wild-type floxed control mice.

Furthermore, in non-DDC-fed livers, β-catenin DsiRNA significantly suppressed both ALA-S and ALA-D expression (Fig. 4C). Similar decreases were also noted in both KO1 and KO2 at base-line (Fig. 4C). A strong TCF4 binding site was identified in the intron region of the Alad gene by ChIP-seq (Fig. S10), which also corresponds to the binding sites for several nuclear receptors like FXR and HNF4. These data indicate ALA-D to be a direct Wnt/β-catenin target, and that suppression of this enzyme inhibits the early steps in the heme biosynthesis pathway, thus reducing protoporphyrin accumulation.

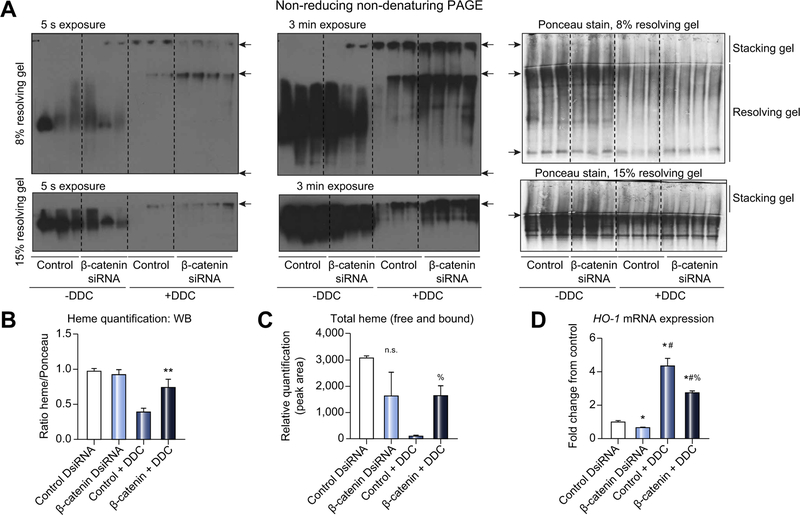

Loss of β-catenin blunts the ability of DDC to deplete hem

Inhibition of heme biosynthesis by DDC results in heme depletion, which in turn inhibits the function of hemoproteins such as Cyps.3,5 We assayed for hepatic heme-containing proteins and found DDC feeding caused massive depletion as expected (Fig. 5A, 5B). However, upon longer exposure, there is residual protein-bound heme apparent in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers compared to control+DDC (Fig. 5A, 5B), indicating reduced heme destruction. A similar trend was observed in denaturing PAGE (Fig. S11). We also measured liver heme levels by LC-MS and found preservation of total heme (free and protein-bound) in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers (Fig. 5C). The increased heme content relative to control+DDC mice could also be a function of decreased heme degradation, which is catalyzed by heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1 or HMOX1).23 Indeed, we found significant repression of HO-1 expression after β-catenin DsiRNA, both before and after DDC (Fig. 5D). Thus, heme depletion as a consequence of DDC is blunted in the absence of β-catenin through multiple mechanisms.

Fig. 5. Loss of β-catenin protects mice from DDC-mediated depletion of heme.

(A) In-gel heme staining shows decreased protein-bound heme in control +DDC but not in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC. Top panels: arrowheads represent bottom of well, stacking-resolving gel junction, and end of gel, respectively. Bottom panels: arrowheads represent stacking-resolving gel junction. (B) Quantification of in-gel heme staining demonstrates loss of heme-bound proteins in control +DDC diet compared to β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC and untreated controls; **p <0.01 vs. control DsiRNA (t test). (C) Measurement of total heme content shows persistence of heme in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC compared to control+DDC; %p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). (D) HO-1 mRNA expression is suppressed in the absence of β-catenin before and after DDC compared to controls; *p <0.05 vs. control DsiRNA, #p <0.05 vs. β-catenin DsiRNA, %p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). For (E) and (F), n = 3 mice per group. DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA.

Loss of β-catenin decreased protein aggregation after DDC

Given that recent studies have shown the unique role of porphyrins in causing protein aggregation,11,12,24 we next analyzed the extent of protein aggregation after DDC. SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining show changes in the protein banding pattern as a function of DDC (Fig. S12A). There is a loss of discrete banding patterns after porphyrin accumulation (iii, iv, v in DDC vs. normal diet fed mice). There is also an accumulation of high molecular weight (HMW) aggregates after DDC (i and ii; loss of band intensity at position iii). Relative to control+DDC, treatment with β-catenin DsiRNA lowered HMW aggregates and increased residual monomer at position iii, which mirrors the difference in porphyrin levels. However, induction of glutathione-S-transferase-mu-1 (GST mu), which is upregulated by oxidative stress, was unchanged between control and β-catenin DsiRNA after DDC, as assessed by Coomassie staining and also validated by immunoblotting (Fig. S12A,12B).9 Thus, while DDC induces protein aggregation, the absence of β-catenin significantly alters the aggregation pattern and reduces total protein aggregates.

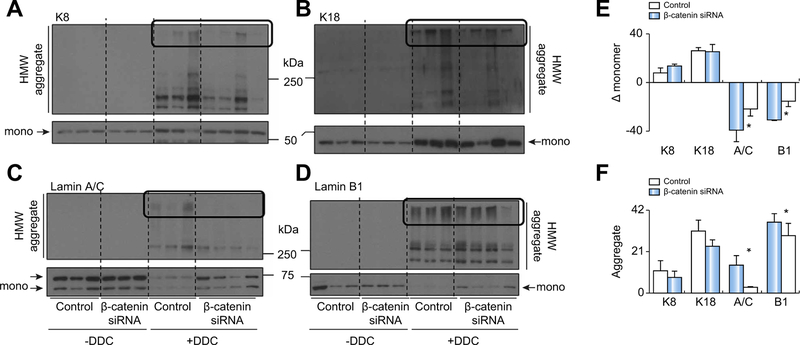

β-Catenin loss mitigates DDC-mediated nuclear intermediate filament (IF) protein damage

Cytosolic (K8/K18) and nuclear (Lamin A/C, Lamin B1) IF proteins have been reported to be highly susceptible to porphyrin-mediated aggregation.11,12,24,25 Indeed, DDC caused upregulation of both K8 and K18 in both control+DDC and β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers as previously described4 (Fig. 6A, 6B, upper panel, and Fig. 6F). DDC feeding also causes loss of nuclear IF proteins and a concomitant increase in HMW aggregates,11 which was reversed in β-catenin+DDC mice (Fig. 6C-F). Thus, loss of β-catenin does not affect cytosolic IF protein damage, but protects against nuclear IF protein damage.

Fig. 6. β-catenin inhibition prevents DDC-mediated nuclear intermediate filament protein damage.

(A) Cytosolic K8 protein expression (in both monomer and HMW aggregate form) is increased in both control and β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers after DDC. (B) Monomeric and aggregate forms of cytosolic K18 are also increased after DDC. (C) Loss in monomeric nuclear lamin A/C after DDC was prevented with β-catenin DsiRNA. (D) β-catenin DsiRNA treatment also preserves the momomeric form of nuclear lamin B1 after DDC. (E) Relative change (with respect to control and β-catenin DsiRNA at baseline) in monomer band intensity after DDC feeding. (F) Quantification of HMW aggregates after DDC feeding in control vs. β-catenin DsiRNA-treated mice. The area of the blot quantified is shown in box. *p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA; HMW, high molecular weight.

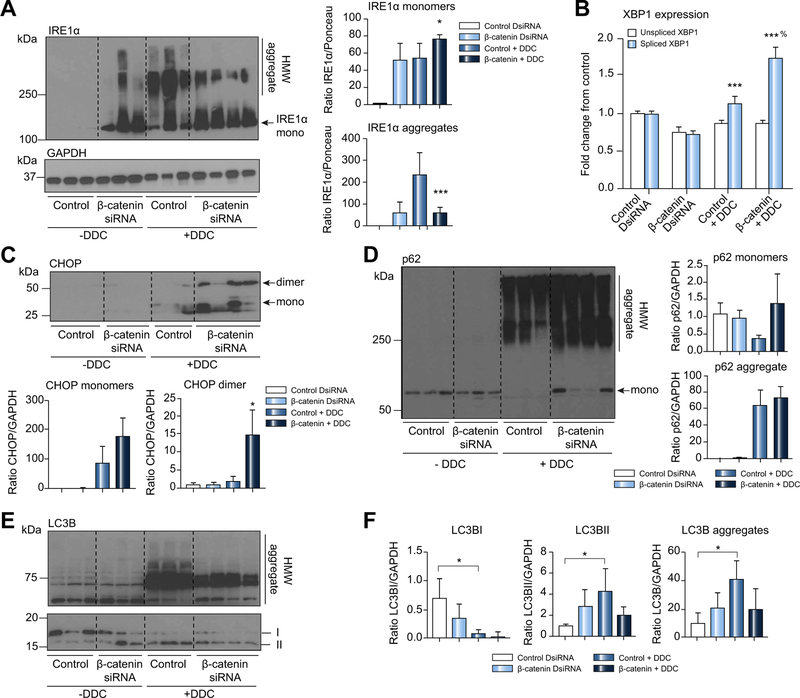

DDC-mediated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein damage and autophagy are attenuated by β-catenin DsiRNA

Previous studies showed that porphyrins cause ER stress through a non-canonical pathway involving ER protein aggregation.11,12 Since IRE1a is essential in activating the unfolded protein response during ER stress, we analyzed its expression before and after DDC. Under basal conditions, we saw increased IRE1a expression in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers (Fig. 7A), which may be due to regulation of antioxidant genes by β-catenin.26 DDC increased formation of HMW aggregates; however, IRE1a monomer was greater in livers of mice treated with β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC than control+DDC livers. IRE1a regulates X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) splicing into a transcriptionally active form that promotes ER-associated protein degradation.27 Spliced XBP1 expression was also increased in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC relative to control+DDC (Fig. 7B). β-Catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers also had higher levels of both the monomer and dimer forms of CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), another mediator of ER stress (Fig. 7C), after DDC diet. Thus, while DDC increases the aggregation of misfolded ER proteins such as IRE1a, this effect is decreased in the absence of β-catenin, leading to increased functionality of the ER stress response.

Fig. 7. β-catenin ameliorates DDC-associated perturbation of protein clearance and autophagy pathways.

(A) Western blotting for IRE1a shows decreased aggregates and increased monomers after β-catenin DsiRNA and DDC compared to controls; *p <0.05 vs. control+DDC; ***p <0.001 vs. control+DDC (t test). (B) Real-time PCR for spliced XBP1 expression shows significant upregulation in β-catenin+DDC-treated livers; ***p <0.001 vs. control; %p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). (C) CHOP is also increased in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers after DDC compared to DDC alone; *p <0.05 vs. control+DDC (t test). (D) Western blotting for p62 shows presence of the monomeric form in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers despite formation of HMW aggregates due to DDC. (E) Western blotting of LC3B proteins shows decrease in the amount of the LC3B I form after DDC, while HMW aggregates increase. (F) Quantification of band intensity from immunoblot shown in (E) demonstrates increased autophagy in controls after DDC but not in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers. LC3B aggregates are also decreased in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated livers; *p <0.05 vs. control DsiRNA (t test). Western blots were quantified using either GAPDH or Ponceau as loading controls. DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; DsiRNA, dicer-substrate RNA; HMW, high molecular weight.

Similarly, HMW aggregates of p62, a poly ubiquitin (Ub) binding protein that is upregulated after DDC,4,28 were also formed to similar extents in both control+DDC and β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC livers (Fig. 7D). This is likely due in part to direct interaction between porphyrin and p62, as a cell-free system utilizing lysed Huh-7 cells treated with PP-IX showed a dramatic loss of p62 monomer and a concomitant increase in HMW aggregate (Fig. S13). However, p62 monomers were also present in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC, with complete loss of monomer observed in control+DDC, suggesting preservation of protein functionality. Our earlier experiments with fluorescent proteasome activity assays had shown that DDC feeding25 and PP-IX treatment11 significantly inhibited proteasome activity, resulting in accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins. Interestingly, however, although both control and β-catenin DsiRNA-treated mice show increased poly-ubiquitinated proteins after DDC, this was slightly reduced by β-catenin inhibition (Fig. S14), suggesting increased functionality of the proteasomal machinery.

Protein aggregation as a function of porphyrin accumulation also induces an autophagic response in order to clear the misfolded proteins.11,12 The amount of LC3BII, which is a measure of autophagy activity in the cell,29 was increased under basal conditions in β-catenin DsiRNA+DDC compared with control +DDC, albeit insignificantly (Fig. 7E,7F). However, after DDC there was no further induction of autophagy over baseline in β-catenin DsiRNA-treated mice, whereas control mice showed a notable increase in LC3BII compared to baseline. In a similar trend, control mice showed higher levels of HMW LC3B aggregates than mice lacking β-catenin (Fig. 7E,7F). Thus, DDC-induced autophagy activation is blunted in the presence of β-catenin DsiRNA, likely because of the decrease in HMW protein aggregates compared to controls.

Discussion

DDC diet leads to accumulation of porphyrin plugs, intermittent bile duct blockage, cholangitis, and biliary fibrosis. Although we have previously shown β-catenin loss from liver results in fewer A6-positive cells and lower bile acid accumulation after DDC, we did not comprehensively characterize the basis of these observations. In this study, we found fewer porphyrin plugs after DDC diet in three models where Wnt/β-catenin signaling was impaired. This is due to suppression of ALA-S and ALA-D, the most proximal event in this process, which in turn decreases production of pathway intermediates such as PP-IX. Loss of these toxic porphyrins resulted in decreased protein aggregation, which reduces subsequent downstream events such as ER stress and autophagy. Thus, we have described a novel and unexpected benefit of inhibiting β-catenin to deactivate the heme biosynthesis pathway, which is often dysregulated in hepatic porphyria.

We show that while ALA-D is likely a direct β-catenin target, ALA-S is not. The inhibition of FC and subsequent heme depletion caused by DDC induces upregulation of ALA-S. Therefore, ALA-S suppression in β-catenin-inhibited livers may be due to a relative increase in heme compared to controls, both at base-line and after DDC. Thus, loss of β-catenin regulates the production of heme enzymes both directly and indirectly. A previous study suggested that reciprocal regulation of Cyps and heme biosynthesis enzymes by β-catenin and Ha-Ras contributed to liver zonality;30 during porphyria, however, continuous activation of the β-catenin pathway may negatively contribute to disease severity through sustained expression of these genes.

Porphyrins are cytotoxic in nature. Recent studies have demonstrated porphyrins induce proteotoxic stress through organelle-specific protein aggregation.11,12,24 Thus, these protein aggregates are surrogates for ER stress and proteasomal inhibition, which contribute to liver injury. Mice treated with β-catenin DsiRNA had fewer protein aggregates, which resulted in maintenance of the monomer forms of proteins involved in ER stress and autophagy. This suggests that the absence of β-catenin preserves the activity of proteins involved in these responses, which in turn ameliorates ER stress and proteotoxicity caused by DDC. Interestingly, protein poly-ubiquitination was decreased after β-catenin inhibition despite comparable p62 aggregation. The presence of HMW p62 aggregates in the absence of β-catenin could be attributed to a direct interaction of porphyrins with p62 as well as inhibition of autophagy, which leads to an increase in both p62 aggregates and total p62 protein levels.31

Previously we described decreased ductular reaction in β-catenin KO mice after DDC. We used A6 as a marker of progenitors, which is also expressed in hematopoietic stem cells.32 Use of more specific cholangiocyte markers like Sox9 and EpCAM33 showed no decrease in ductular response in any β-catenin-deficient model, indicating that ductular reaction may be autonomous of porphyrin accumulation. Bile acids, which were equivalent in both groups, can stimulate cholangiocyte proliferation.34 Reduced bile flow reported in β-catenin KO may impede removal of porphyrin plugs from canaliculi after β-catenin inhibition,35 and be another mechanism of persistent ductular response. Finally, Wnt secretion from cholangiocytes also regulates ductular response after DDC.36 Thus, ductular reaction in DDC may be driven by factors independent of the extent of porphyrin accumulation.

Similarly, comparable fibrosis observed in WT1, KO1, WT2, and KO2 after 2 weeks of DDC could be attributed to similar ductular reaction, which has been shown to play a role in biliary fibrosis through activation of stellate cells and portal fibroβ-lasts.37 Intriguingly, mice treated with β-catenin DsiRNA did show a significant decrease in fibrosis after 4 weeks of DDC, similar to our previously reported findings in KO1.15 We believe that after initiation by reactive ductules, ongoing chronic injury perpetuates fibrosis. This leads to a divergent fibrotic response despite comparable ductular reaction, with controls showing an exacerbation of fibrosis while β-catenin loss prevents worsening of fibrosis due to decreased injury.

A previous study showed mice lacking β-catenin had increased liver injury after 21 days of DDC due to increased oxidative stress.38 The authors inducibly knocked down hepatocyte β-catenin which resulted in >50% decrease in β-catenin expression. The differences between the studies may be explained by the insufficient knockdown of β-catenin achieved in their model. Indeed, a subsequent publication by our lab has shown that a small subset of hepatocytes in baseline KO1 livers that escaped albumin-cre mediated β-catenin deletion had proliferative and survival advantages, repopulating KO1 livers after long-term DDC.39 This was accompanied by significantly increased fibrosis and cholestasis compared to WT1.39 We did not observe any β-catenin positive hepatocyte nodules in any of our mouse models after 1 month of DDC, a finding which was reproducible over several studies and models.14,15 Therefore, we believe we achieved effective penetrance of β-catenin inhibition, which alleviated DDC-induced porphyria in the short term.

Extrahepatic (erythropoietic) or hepatic porphyria in humans is a result of alterations in specific enzymes of the heme biosynthesis pathway. Although only 15% of heme is synthesized in the liver, it is commonly either a source or a target of excess porphyrins in several types of porphyria, including acute intermittent porphyria.40 Liver-related dysfunction can range from minor abnormalities to liver failure. In our mouse models, we demonstrated that inhibiting β-catenin protected livers from porphyria-induced injury. This effect was multifactorial, including suppression of ALA-D and HO-1, and negative feedback regulation of ALA-S (Fig. S15). We are aware of negative effects of long-term β-catenin suppression, which may disrupt redox homeostasis41,42 and hence caution against sustained β-catenin inhibition; however, treatment cycles with a β-catenin suppressor may be both safe and efficacious at ameliorating liver injury caused by porphyrin disorders.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.023.

Highlights.

Porphyrias are caused by defects in heme biosynthesis, which can lead to cholestasis, inflammation, and fibrosis.

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a role in pathological processes in the liver, including cholestasis and biliary injury.

Inhibiting β-catenin in a mouse model of porphyria resulted in decreased liver injury.

Several key heme biosynthesis enzymes were downregulated in livers lacking β-catenin signaling.

Mice lacking β-catenin had fewer protein aggregates, resulting in improved proteasomal activity and less autophagy.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This study was funded by NIH grants R01 DK62277 and R01 DK100287 and Endowed Chair for Experimental Pathology to SPSM; NIH grant R01 DK103775 to KNB; and NIH grant R01 DK116548 to MBO.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr. Monga is on the scientific advisory board for Abbvie Pharmaceuticals and has a corporate research agreement with Dicerna Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Abrams is employed by Dicerna Pharmaceuticals. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

- [1].Schultz IJ, Chen C, Paw BH, Hamza I. Iron and porphyrin trafficking in heme biogenesis. J Biol Chem 2010;285:26753–26759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ajioka RS, Phillips JD, Kushner JP. Biosynthesis of heme in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1763:723–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tephly TR, Gibbs AH, Ingall G, De Matteis F. Studies on the mechanism of experimental porphyria and ferrochelatase inhibition produced by 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine. Int J Biochem 1980;12:993–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zatloukal K, French SW, Stumptner C, Strnad P, Harada M, Toivola DM, et al. From Mallory to Mallory-Denk bodies: what, how and why? Exp Cell Res 2007;313:2033–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Correia MA, Sinclair PR, De Matteis F. Cytochrome P450 regulation: the interplay between its heme and apoprotein moieties in synthesis, assembly, repair, and disposal. Drug Metab Rev 2011;43:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brady AM, Lock EA. Inhibition of ferrochelatase and accumulation of porphyrins in mouse hepatocyte cultures exposed to porphyrinogenic chemicals. Arch Toxicol 1992;66:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yasuda M, Gan L, Chen B, Kadirvel S, Yu C, Phillips JD, et al. RNAi-mediated silencing of hepatic Alas1 effectively prevents and treats the induced acute attacks in acute intermittent porphyria mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:7777–7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fickert P, Trauner M, Fuchsbichler A, Stumptner C, Zatloukal K, Denk H. Bile acid-induced Mallory body formation in drug-primed mouse liver. Am J Pathol 2002;161:2019–2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hanada S, Snider NT, Brunt EM, Hollenberg PF, Omary MB. Gender dimorphic formation of mouse Mallory-Denk bodies and the role of xenobiotic metabolism and oxidative stress. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1607–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ku NO, Strnad P, Zhong BH, Tao GZ, Omary MB. Keratins let liver live: Mutations predispose to liver disease and crosslinking generates Mallory-Denk bodies. Hepatology 2007;46:1639–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maitra D, Elenbaas JS, Whitesall SE, Basrur V, D’Alecy LG, Omary MB. Ambient light promotes selective subcellular proteotoxicity after endogenous and exogenous porphyrinogenic stress. J Biol Chem 2015;290:23711–23724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Elenbaas JS, Maitra D, Liu Y, Lentz SI, Nelson B, Hoenerhoff MJ, et al. A precursor-inducible zebrafish model of acute protoporphyria with hepatic protein aggregation and multiorganelle stress. FASEB J 2016;30:1798–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fickert P, Stoger U, Fuchsbichler A, Moustafa T, Marschall HU, Weiglein AH, et al. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2007;171:525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Apte U, Thompson MD, Cui S, Liu B, Cieply B, Monga SP. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates oval cell response in rodents. Hepatology 2008;47:288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thompson MD, Moghe A, Cornuet P, Marino R, Tian J, Wang P, et al. beta-catenin regulation of farnesoid X receptor signaling and bile acid metabolism during murine cholestasis. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [16].Tan X, Behari J, Cieply B, Michalopoulos GK, Monga SP. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin reveals its role in liver growth and regeneration. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1561–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang J, Mowry LE, Nejak-Bowen KN, Okabe H, Diegel CR, Lang RA, et al. Beta-catenin signaling in murine liver zonation and regeneration: A Wnt-Wnt situation! Hepatology 2014;60:964–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nejak-Bowen K, Kikuchi A, Monga SP. Beta-catenin-NF-kappaB interactions in murine hepatocytes: a complex to die for. Hepatology 2013;57:763–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yamazaki Y, Moore R, Negishi M. Nuclear receptor CAR (NR1I3) is essential for DDC-induced liver injury and oval cell proliferation in mouse liver. Lab Invest 2011;91:1624–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Braeuning A, Heubach Y, Knorpp T, Kowalik MA, Templin M, Columbano A, et al. Gender-specific interplay of signaling through beta-catenin and CAR in the regulation of xenobiotic-induced hepatocyte proliferation. Toxicol Sci 2011;123:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hunter GA, Ferreira GC. Molecular enzymology of 5-aminolevulinate synthase, the gatekeeper of heme biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1814:1467–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dailey HA, Meissner PN. Erythroid heme biosynthesis and its disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2013;3 a011676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kikuchi G, Yoshida T, Noguchi M. Heme oxygenase and heme degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;338:558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Singla A, Griggs NW, Kwan R, Snider NT, Maitra D, Ernst SA, et al. Lamin aggregation is an early sensor of porphyria-induced liver injury. J Cell Sci 2013;126:3105–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Singla A, Moons DS, Snider NT, Wagenmaker ER, Jayasundera VB, Omary MB. Oxidative stress, Nrf2 and keratin up-regulation associate with Mallory-Denk body formation in mouse erythropoietic protoporphyria. Hepatology 2012;56:322–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Essers MA, de Vries-Smits LM, Barker N, Polderman PE, Burgering BM, Korswagen HC. Functional interaction between beta-catenin and FOXO in oxidative stress signaling. Science 2005;308:1181–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu X, Henkel AS, LeCuyer BE, Schipma MJ, Anderson KA, Green RM. Hepatocyte X-box binding protein 1 deficiency increases liver injury in mice fed a high-fat/sugar diet. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;309:G965–G974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Harada M, Hanada S, Toivola DM, Ghori N, Omary MB. Autophagy activation by rapamycin eliminates mouse Mallory-Denk bodies and blocks their proteasome inhibitor-mediated formation. Hepatology 2008;47:2026–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol 2008;445:77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Braeuning A, Schwarz M. Zonation of heme synthesis enzymes in mouse liver and their regulation by beta-catenin and Ha-ras. Biol Chem 2010;391:1305–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol 2005;171:603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Petersen BE, Grossbard B, Hatch H, Pi L, Deng J, Scott EW. Mouse A6-positive hepatic oval cells also express several hematopoietic stem cell markers. Hepatology 2003;37:632–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Li B, Dorrell C, Canaday PS, Pelz C, Haft A, Finegold M, et al. Adult mouse liver contains two distinct populations of cholangiocytes. Stem Cell Rep 2017;9:478–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Alpini G, Glaser SS, Ueno Y, Rodgers R, Phinizy JL, Francis H, et al. Bile acid feeding induces cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion: evidence for bile acid-regulated ductal secretion. Gastroenterology 1999;116:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yeh TH, Krauland L, Singh V, Zou B, Devaraj P, Stolz DB, et al. Liver-specific beta-catenin knockout mice have bile canalicular abnormalities, bile secretory defect, and intrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology 2010;52:1410–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Okabe H, Yang J, Sylakowski K, Yovchev M, Miyagawa Y, Nagarajan S, et al. Wnt signaling regulates hepatobiliary repair following cholestatic liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2016;64:1652–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Miller T, Alvaro D, Alpini G. Cholangiocyte proliferation and liver fibrosis. Expert Rev Mol Med 2009;11 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tao GZ, Lehwald N, Jang KY, Baek J, Xu B, Omary MB, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling protects mouse liver against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis through the inhibition of forkhead transcription factor FoxO3. J Biol Chem 2013;288:17214–17224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Thompson MD, Wickline ED, Bowen WB, Lu A, Singh S, Misse A, et al. Spontaneous repopulation of beta-catenin null livers with beta-catenin-positive hepatocytes after chronic murine liver injury. Hepatology 2011;54:1333–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet 2010;375:924–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nejak-Bowen KN, Zeng G, Tan X, Cieply B, Monga SP. Beta-catenin regulates vitamin C biosynthesis and cell survival in murine liver. J Biol Chem 2009;284:28115–28127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang XF, Tan X, Zeng G, Misse A, Singh S, Kim Y, et al. Conditional beta-catenin loss in mice promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis: role of oxidative stress and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha/phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Hepatology 2010;52:954–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.023.