FOLFIRI‐Ram has emerged as a reasonable second‐line option for patients with advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. This article examines the safety and efficacy of second‐line FOLFIRI‐ram across a clinically‐annotated and molecularly characterized U.S. cohort.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, GEJ adenocarcinoma, Ramucirumab, FOLFIRI, Second line

Abstract

Background.

The randomized phase III RAINBOW trial established paclitaxel (pac) plus ramucirumab (ram) as a global standard for second‐line (2L) therapy in advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, together gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA). Patients (pts) receiving first‐line (1L) FOLFOX often develop neuropathy that renders continued neurotoxic agents in the 2L setting unappealing and other regimens more desirable. As such, FOLFIRI‐ram has become an option for patients with 2L GEA. FOLFIRI‐ramucirumab (ram) has demonstrated safety and activity in 2L colorectal cancer, but efficacy/safety data in GEA are lacking.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods.

Patients with GEA treated with 2L FOLFIRI‐ram between August 2014 and April 2018 were identified. Clinicopathologic data including oxaliplatin neurotoxicity rates/grades (G), 2L treatment response, progression‐free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), safety, and molecular features were abstracted from three U.S. academic institutions. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis was used to generate PFS/OS; the likelihood ratio test was used to determine statistical significance.

Results.

We identified 29 pts who received 2L FOLFIRI‐ram. All pts received 1L platinum + fluoropyrimidine, and 23 of 29 (79%) had post‐1L neuropathy; 12 (41%) had G1, and 11 (38%) had G2. Patients were evenly split between esophagus/gastroesophageal junction (12; 41%) and gastric cancer (17; 59%). Among evaluable pts (26/29), the overall response rate was 23% (all partial response) with a disease control rate of 79%. Median PFS was 6.0 months and median OS was 13.4 months among all evaluable pts. Six‐ and 12‐month OS were 90% (n = 18/20) and 41% (n = 7/17). There were no new safety signals.

Conclusion.

We provide the first data suggesting FOLFIRI‐ram is a safe, non‐neurotoxic regimen comparing favorably with the combination of pac + ram used in the seminal RAINBOW trial.

Implications for Practice.

Results of this study provide initial support for the safety and efficacy of second‐line (2L) FOLFIRI‐ramucirumab (ram) after progression on first‐line platinum/fluoropyrimidine in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA). The overall response, progression‐free survival, overall survival, and toxicity profile compare favorably with paclitaxel (pac) + ram and highlight the importance of the ongoing phase II RAMIRIS trial examining FOLFIRI‐ram versus pac + ram in 2L GEA (NCT03081143). FOLFIRI‐ram may warrant consideration for inclusion as an alternate regimen in consensus guidelines for GEA.

摘要

背景。随机 III 期 RAINBOW 试验制定了紫杉醇 (pac) 和雷莫芦单抗 (ram) 作为晚期胃部和胃食管结合部腺癌,统称为胃食管腺癌 (GEA),二线 (2L) 治疗的全球标准。接受一线 (1L) FOLFOX 治疗的患者 (pt) 通常会出现神经病变,这使得在 2L 环境中持续使用神经毒剂不具吸引力,而其他疗法则更为可取。因此,FOLFIRI‐雷莫芦单抗 (ram) 成为 2L GEA 患者的一种选择。FOLFIRI‐ ram已在 2L 结直肠癌治疗中显示出安全性和活性,但是,在 GEA 治疗中尚缺乏有效性/安全性数据。

受试者、材料和方法。我们找出在 2014 年 8 月至 2018 年 4 月期间接受 2L FOLFIRI‐ram 治疗的 GEA 患者。从三个美国学术机构中提取包括奥沙利铂神经毒性率/等级 (G)、2L 治疗反应、无进展生存期 (PFS)、总生存期 (OS)、安全性以及分子特性在内的临床病理数据。Kaplan‐Meier 生存分析用于生成 PFS/OS;似然比检验用于确定统计显著性。

结果。我们找到 29 名接受 2L FOLFIRI‐ram 治疗的患者。所有患者均接受 1L 铂类 + 氟尿嘧啶类治疗,29 名患者中的 23 名患者 (79%) 出现 1L 后神经病变;12 名患者 (41%) 为 G1,11 名患者 (38%) 为 G2。患者均匀地分布于食道/胃食管结合部癌症(12 名患者;41%)和胃癌(17 名患者;59%)之间。在可评价的患者(29 名患者中的 26 名患者)中,总缓解率为 23%(全部为部分缓解),疾病控制率为 79%。在所有可评价的患者中,中位 PFS 为 6.0 个月,中位 OS 为 13.4 个月。6 个月 OS 和 12 个月 OS 分别占 90% (n = 18/20) 和 41% (n = 7/17)。没有新的安全信号。

结论。我们提供了首个数据表明 FOLFIRI‐ram 是一种不会毒害神经的安全疗法,可以与创新性 RAINBOW 试验中使用的 pac + ram 联合治疗相媲美。

实践意义:本研究结果对胃食管腺癌 (GEA) 患者在一线铂类/氟尿嘧啶类治疗出现进展后的二线 (2L) FOLFIRI‐雷莫芦单抗(ram) 治疗提供初步支持。总体反应、无进展生存期、总生存期以及毒性特征可以与紫杉醇 (pac) + ram 相媲美,并强调了旨在于 2L GEA (NCT03081143) 中检验 FOLFIRI‐ram 对比 pac + ram 的正在进行的 II 期 RAMIRIS 试验的重要性。可能值得考虑的是,将 FOLFIRI‐ram 作为一种替代疗法列入 GEA 的共识指南。

Introduction

Gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA) accounts for over 1.1 million annual cancer‐related deaths, representing nearly 14% of global cancer deaths [1]. Despite improved molecular characterization, the prevailing international standard for advanced GEA remains doublet therapy with platinum‐based and fluoropyrimidine (5FU)‐based combination regimens [2], [3]. The addition of trastuzumab to first‐line (1L) platinum/5FU in HER2‐positive patients improves survival in this molecularly selected subset [4]. Among U.S. patients there is significant 1L regimen heterogeneity, with FOLFOX being the most common platinum/5FU combination. Following 1L therapy, U.S. claims analyses suggest only 42%–54% of patients with GEA receive second‐line (2L) therapy [5], [6]. The phase III RAINBOW trial established the combination of paclitaxel (pac) and the anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2 antibody ramucirumab (ram) as a global 2L standard after platinum/5FU failure [7]. However, the rates of neurotoxicity with 1L FOLFOX in GEA range from 30%–70%, making 2L taxane‐containing therapy less appealing to a significant portion of patients with GEA [8], [9]. Moreover, the use of prior taxane regimens in the 1L setting, or rapid recurrence after perioperative FLOT therapy, makes determining an optimal “2L” taxane‐free regimen of critical importance [10], [11], [12], [13]. Irinotecan as either monotherapy or in combination with 5FU (FOLFIRI) has established activity in GEA as both a 1L and 2L option [14], [15]. A small (n = 6) Japanese phase Ib trial of irinotecan plus ramucirumab (no 5FU) in more heavily pretreated gastric cancer demonstrated safety and a response rate of 17% (1/6) [16]. Additional support for the safety and efficacy of FOLFIRI in combination with ramucirumab (FOLFIRI‐ram) was established in a phase III trial in 2L advanced colorectal cancer after progression on FOLFOX with bevacizumab [17].

Despite the lack of data, FOLFIRI‐ram has emerged as a reasonable 2L option for a significant portion of patients with advanced disease across U.S. institutions. We therefore sought to examine the safety and efficacy of 2L FOLFIRI‐ram across a clinically annotated and molecularly characterized U.S. cohort with GEA.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Patients with advanced GEA who were treated with 2L FOLFIRI‐ram were retrospectively identified from three tertiary U.S. medical centers. All patients fulfilled prespecified inclusion criteria, including histologically confirmed advanced GEA, 1L platinum + 5FU‐based chemotherapy, receipt of at least two cycles of FOLFIRI‐ram, and available clinicopathologic details. All patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and retrospective review was approved by the respective local institutional review board. Clinicopathologic details were abstracted, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 was used to grade adverse events, and RECIST v1.1 per investigator assessment was utilized for response assessment. HER2 testing was performed locally at diagnosis per American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)/College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines. Where possible, programmed death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) status was determined using the Food and Drug Administration‐approved pharmDx (Agilent; Santa Clara, CA) immunohistochemical (IHC) assay (PD‐L1 IHC 22C3) combined positive score as previously described [18]. Comprehensive genomic profiling was performed using hybrid‐capture‐based genomic profiling as previously described (FoundationOne; Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA) [19].

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initiation of 2L therapy to death. Progression‐free survival (PFS) was calculated from both the start of 1L therapy to disease progression and the start of 2L FOLFIRI‐ram to progression or death. Times to event (PFS/OS) were estimated using the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared using log‐rank and Cox proportional hazards, with the likelihood ratio used to determine statistical significance. For genomic analyses, PFS and OS Cox univariate and multivariate regression models were developed to analyze the role of individual alterations and predetermined pathway activation on outcomes. All inferential analyses utilized two‐sided methods (α = 0.05), and statistical significance was determined when p value was <.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.2.

Results

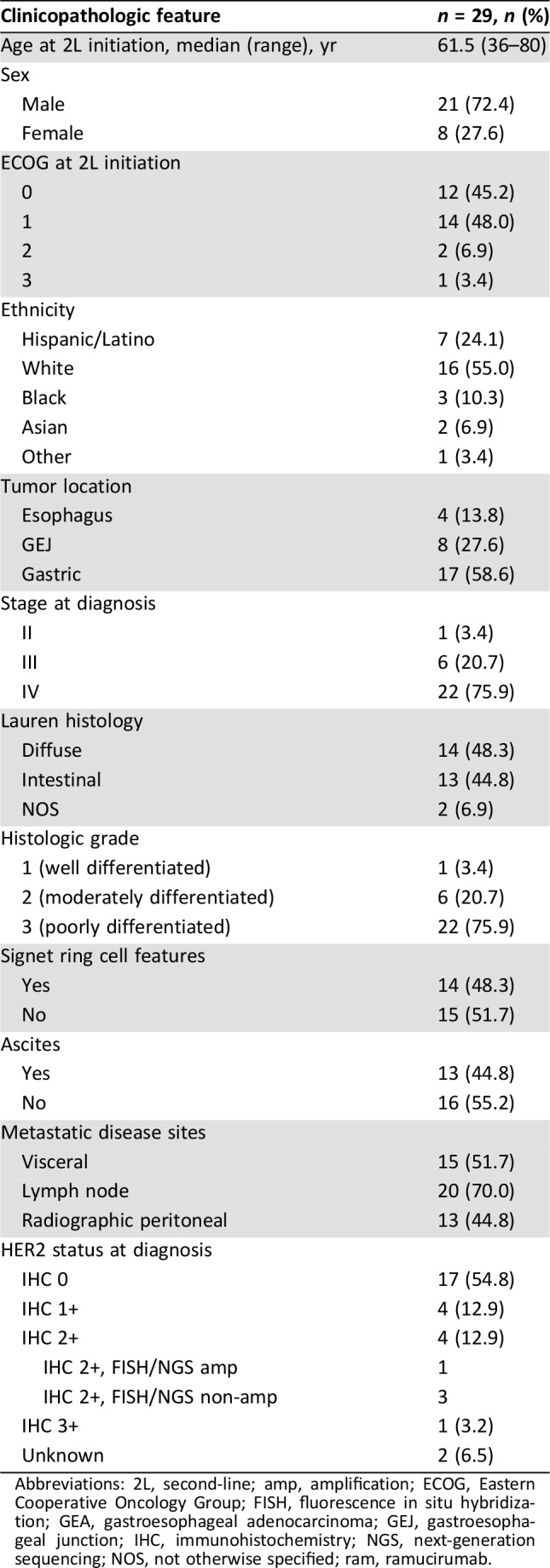

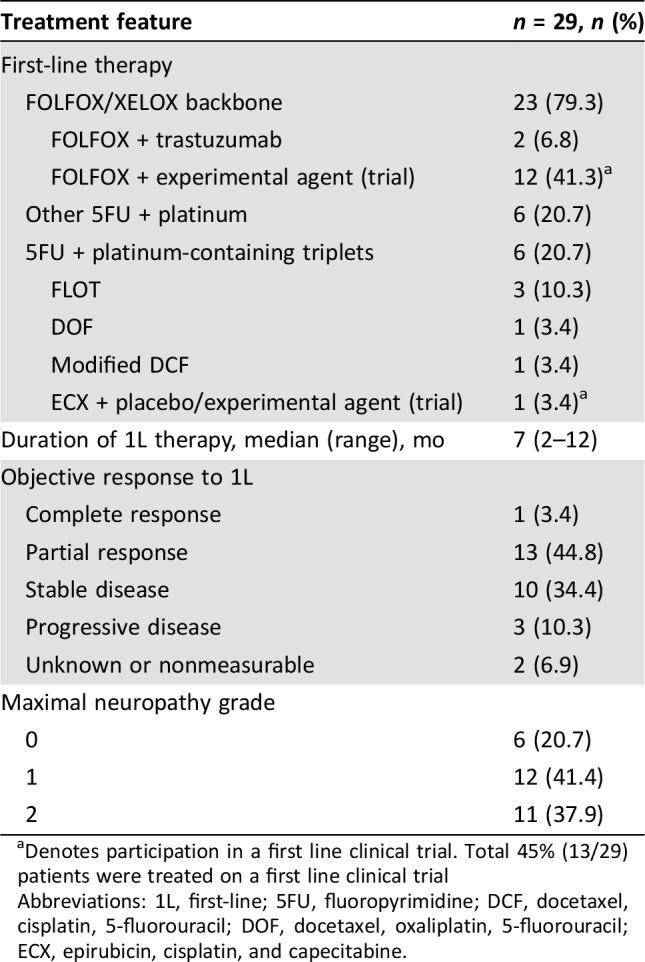

A total of 29 patients met the prespecified inclusion criteria and received 2L FOLFIRI‐ram between August 2014 and April 2018, and 26 of 29 patients were evaluable for PFS and OS analyses. Baseline demographic and pathologic features are shown in Table 1. The majority (75%) presented with stage IV disease, and poor prognostic features, including peritoneal disease (45%), ascites (45%), and signet ring cell features (45%), were common. Forty‐five percent of patients participated in first‐line clinical trials, and all patients received first‐line platinum plus 5‐fluorouracil (5FU)‐containing regimens, with the majority (79%) receiving FOLFOX/XELOX (Table 2). The overall response rate to 1L therapy was 48% with a median 1L therapy duration of 7 months, consistent with phase II–III platinum/5FU containing 1L trials (Table 2) [8], [9], [20], [21]. Post‐1L neuropathy was seen in 79% of patients, and nearly 40% had grade 2 neuropathy.

Table 1. Clinicopathologic features in a cohort of GEA patients treated with second‐line FOLFIRI‐ram.

Abbreviations: 2L, second‐line; amp, amplification; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GEA, gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NGS, next‐generation sequencing; NOS, not otherwise specified; ram, ramucirumab.

Table 2. First‐line treatment outcomes in a cohort of GEA patients treated with second‐line FOLFIRI + ram.

Denotes participation in a first line clinical trial. Total 45% (13/29) patients were treated on a first line clinical trial

Abbreviations: 1L, first‐line; 5FU, fluoropyrimidine; DCF, docetaxel, cisplatin, 5‐fluorouracil; DOF, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, 5‐fluorouracil; ECX, epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine.

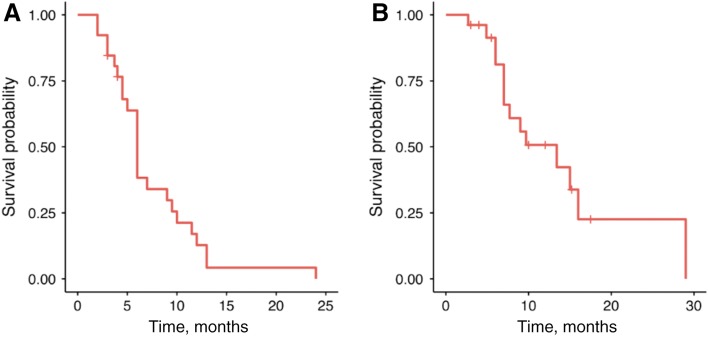

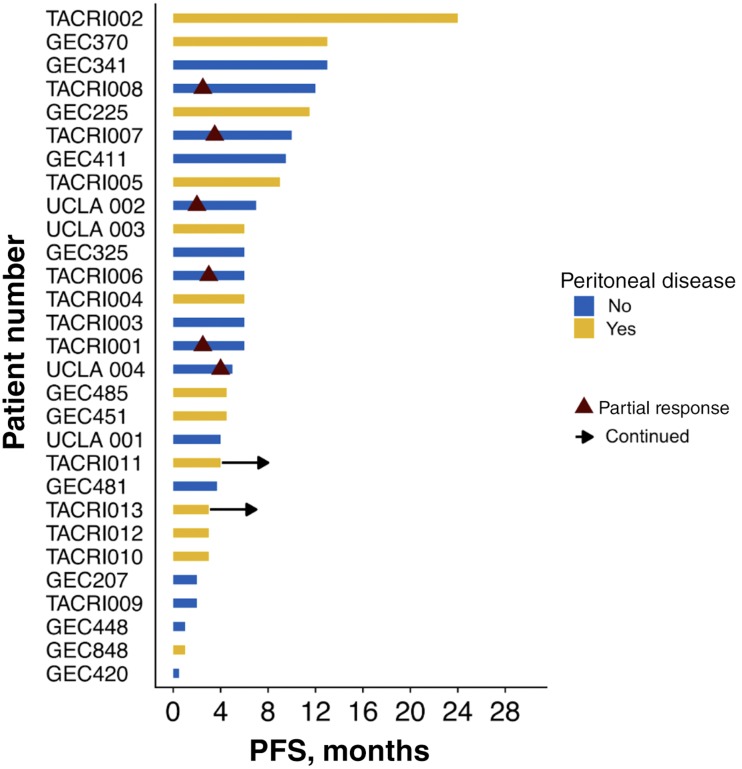

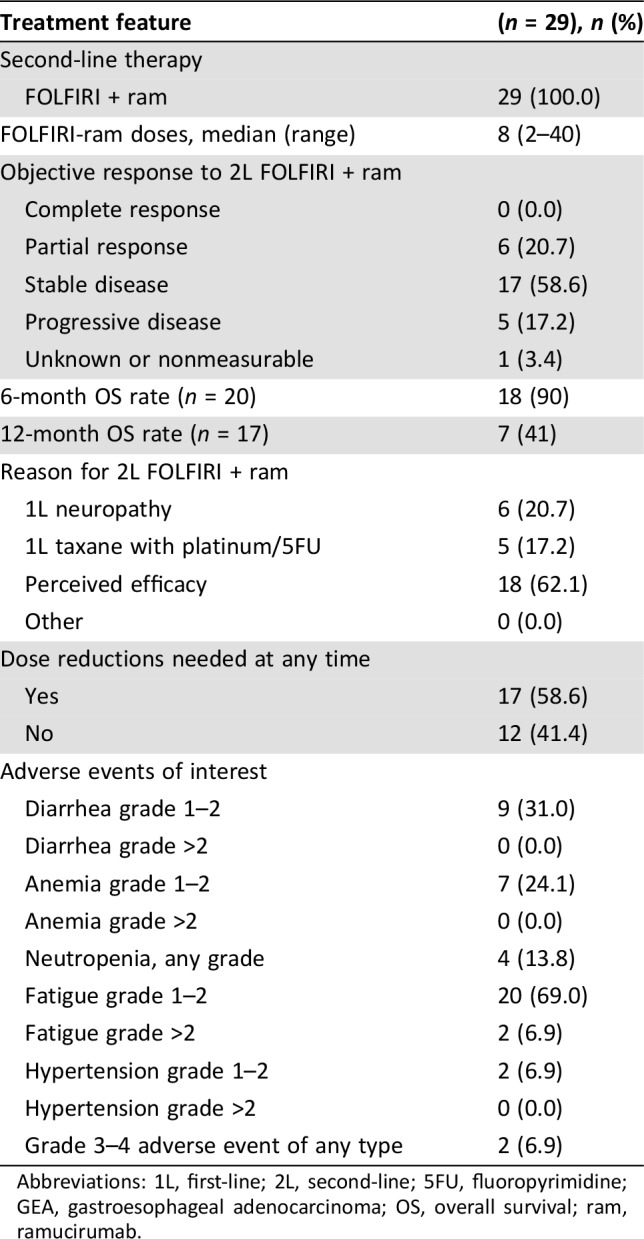

The most common reason for selecting second‐line FOLFIRI‐ram was perceived efficacy (62%), followed by persistent post‐1L neuropathy (21%) and receipt of 1L taxane (17%; Table 3). Amongst the 26 evaluable patients, median PFS and OS for 2L FOLFIRI‐ram were 6 and 13.4 months, respectively (Fig. 1). Progression‐free survival ranged from 2 to 24 months, and 2 patients remained on therapy at the time of censoring (June 1, 2018). The RECIST v1.1 disease control rate was 79% (23/26), and objective response rate in evaluable patients was 23% (6/26), consisting entirely of partial responses. Of note, all six patients with objective responses lacked peritoneal disease, and four of six had proximal disease (Fig. 2). Six‐ and 12‐month OS were 90% (n = 18/20) and 41% (n = 7/17), respectively. Toxicities were largely grade 1–2, with only 6.9% developing grade 3–4 adverse events (all grade 3 fatigue). Fatigue (75.6%), diarrhea (31%), anemia (24.1%), and neutropenia (13.8%) were the most common adverse events, and there were no toxic deaths (Table 3). Adverse events potentially associated with the VEGF pathway were uncommon, with 6.9% (2/29) of patients developing grade 1–2 hypertension and no bleeding events. Rates of proteinuria were not well captured in this retrospective cohort; however, there were no reported cases of nephrotic syndrome.

Table 3. Response characteristics and toxicity profile in a cohort of advanced GEA patients receiving second line FOLFIRI in combination with ramucirumab.

Abbreviations: 1L, first‐line; 2L, second‐line; 5FU, fluoropyrimidine; GEA, gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma; OS, overall survival; ram, ramucirumab.

Figure 1.

Median progression‐free survival was 6 months (A), and median overall survival was 13.4 months (B) across the 26 evaluable patients.

Figure 2.

Swimmer plot of progression free survival by patient demonstrating RECIST responses only occurring in patients without peritoneal involvement.Abbreviation: PFS, progression‐free survival.

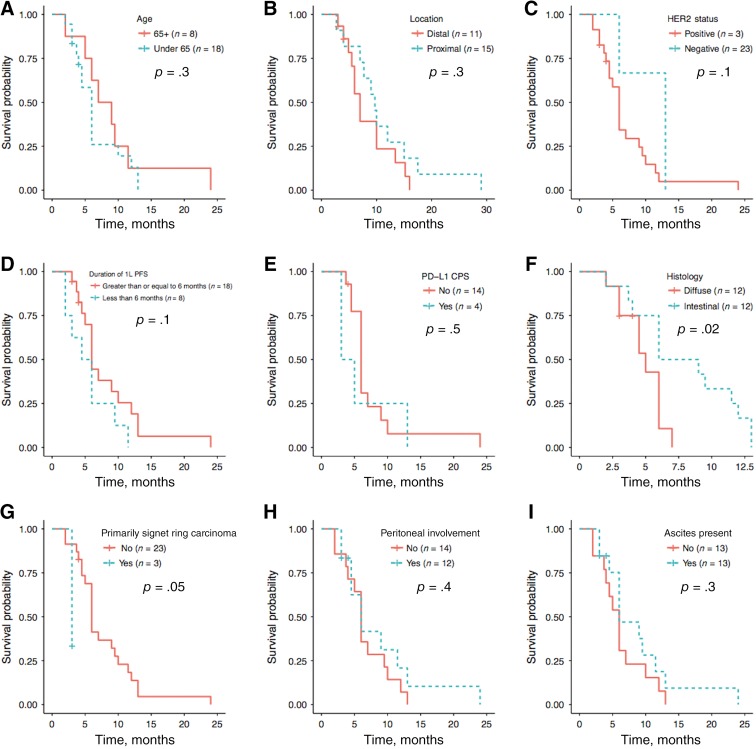

Univariate analysis identified a significantly better median PFS of 7.5 versus 5 months in intestinal versus diffuse type histology (n = 12/24; p = .02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1–0.9; Fig. 3F) and inferior median PFS in patients with predominantly signet cells (n = 3; p = .05; 95% CI, 1.1–57.3; Fig. 3G). No significant PFS differences were seen when stratified by age, location, HER2 status, PD‐L1 expression, or ascites or peritoneal disease. Patients with first‐line therapy responses of 6 or more months had a median OS of 15 versus 7 months compared to those with shorter first‐line responses (online supplemental Fig. 1D). There was no significant association of patient age, presence of signet cells, ascites, or peritoneal disease with median overall survival.

Figure 3.

Patients 65 and older (n = 8/26) had an 8‐month median progression‐free survival (mPFS) versus 6 months in younger patients (p = .3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6–3.7) (A). Patients with proximal gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA; n = 11/26) trended towards mPFS of 9.7 versus 7 months (p = .3; 95% CI, 0.3–1.5) (B). HER2 positive patients (n = 3/26) had an mPFS of 13 versus 6 months, although this was not statistically significant (p = .1, 95% CI, 0.1–1.5) (C). Those with first‐line therapy mPFS <6 months (n = 8/26) had a second‐line mPFS of 5.3 months versus 6 months for those with a 6 month or greater first‐line PFS (p = .1, 95% CI, 0.8–4.9) (D). PD‐L1 negative patients (n = 14/18) tested by immunohistochemistry had a nonsignificant mPFS benefit of 6 versus 4 months (p = .5; 95% CI, 0.5–4.8) (E). Median progression‐free survival was 7.5 versus 5 months in patients with intestinal (n = 12/24) versus diffuse type histology (n = 12/24; p = .02; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9) (F). Similarly, 3 of 24 patients with known histology had predominantly signet cell carcinoma, and this portended a 3‐ versus 6‐month mPFS (p = .05, 95% CI, 1.1–57.3) (G). Median PFS was 6 months in patients with peritoneal involvement (n = 12/26; p = .4; 95% CI, 0.3–1.7) (H) and ascites (n = 13/26; p = .3, 95% CI, 0.3–1.5) (I).Abbreviations: 1L, first‐line; CPS, combined positive score; PD‐L1, programmed death ligand 1; PFS, progression‐free survival.

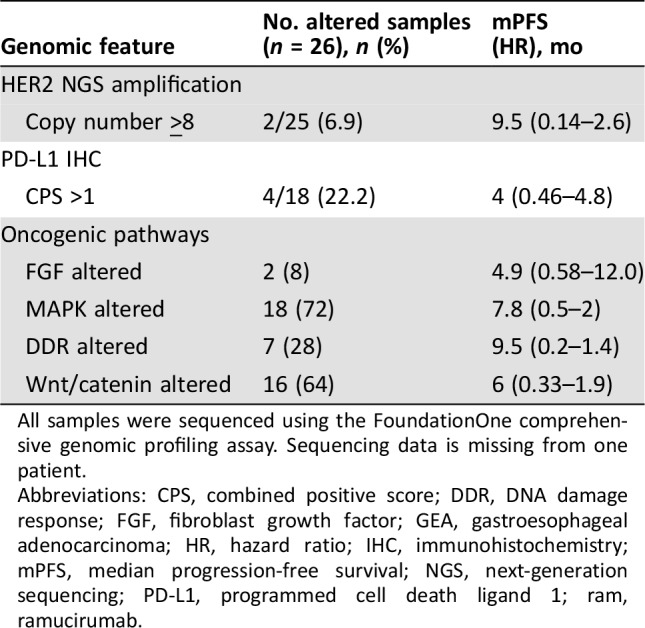

All patients had molecular characterization, with 28 of 29 (96.6%) patients undergoing genomic profiling. All patients with available results (next‐generation sequencing and/or IHC) were microsatellite stable, and 20% (4/20 tested) were PD‐L1 positive. Molecular testing results and impact on FOLFIRI‐ram PFS and OS are shown in Table 4. Among included genes, there were no statistically significant associations between individual gene alteration or pathway and clinical outcomes upon univariate analysis (data not shown). However, upon multivariate pathway analysis, including alterations in Wnt, FGF, DDR, or MAPK, the “wildtype Wnt” (i.e., no Wnt pathway genomic alterations) covariate suggested a median OS benefit (p = .01; data not shown).

Table 4. Genomic features among evaluable GEA patients who received 2L FOLFIRI‐ram.

All samples were sequenced using the FoundationOne comprehensive genomic profiling assay. Sequencing data is missing from one patient.

Abbreviations: CPS, combined positive score; DDR, DNA damage response; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GEA, gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry; mPFS, median progression‐free survival; NGS, next‐generation sequencing; PD‐L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; ram, ramucirumab.

Discussion

Here we provide the first report of 2L FOLFIRI‐ram in patients with advanced GEA treated with 1L platinum/5FU‐based chemotherapy. Although limited by its retrospective nature, our analyses suggest FOLFIRI‐ram is a safe and non‐neurotoxic 2L regimen with favorable activity.

Since the 2014 approval of paclitaxel with ram, there have been no significant advancements in the 2L treatment of GEA, including HER2‐directed therapies and immunotherapy [7], [22], [23]. Outside molecular subgroups such as microsatellite instability high, pac + ram remains the standard 2L therapy. Early support for 2L FOLFIRI was observed in the phase III epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine (ECX) versus FOLFIRI 1L trial, in which 48% of patients receiving first‐line ECX received 2L FOLFIRI. Among the 2L FOLFIRI patients, the overall response rate (ORR) was 13.7%, although second‐line PFS2 was not reported [14]. Pilot support for irinotecan with ramucirumab was also shown in a small phase Ib (n = 6) Japanese trial [16]. Phase III trials utilizing paclitaxel monotherapy control arms reliably demonstrate ORR of 13%–20%, with PFS ranging from 3–4 months [7], [22], [23]. Although we cannot directly compare our retrospective data to prospective clinical trial data, our ORR of 23% and median PFS of 6 months compare favorably with 2L GEA trials. Landmark survival analyses, specifically 6‐ and 12‐month OS rates, are meaningful endpoints, and the 6‐ and 12‐months OS rates of 90% and 41% observed in our cohort are well aligned with the RAINBOW results (72% and 40%, respectively) [7].

Treatment‐associated toxicities impact the quality of life among patients with GEA, and the balance of efficacy and tolerance is particularly important in later lines of therapy. The adverse‐event related treatment discontinuation rate was 12% for pac + ram with grade 3 events in 47% of patients [7]. We observed a favorable toxicity profile with FOLFIRI‐ram with grade 3 adverse events in 7%, although 58% of our patients required dose reduction during therapy. Admittedly, these comparisons should be considered exploratory, and the ongoing phase II RAMIRIS trial (NCT03081143) will provide key data.

The clinicopathologic features among our patients are representative of U.S. patients with GEA. Consistent with prior reports, we observed lesser benefit among patients with diffuse type histology and signet ring cell features [7], [24]. The exact biologic rationale for this observation is unknown, and predictive and prognostic genomic biomarkers are essential to improving outcomes in GEA. Molecularly defined subsets including HER2 amplification, EGFR amplification, MET amplification, and microsatellite instable, PD‐L1 positive, and EBV‐positive tumors have met with variable success when matched to targeted and/or immune therapies [4], [9], [18], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. To date, there have been no biomarkers clearly associated with ram in GEA, although high VEGF‐D (>115pg/mL) may identify a group with improved outcomes in the RAISE trial [32]. In the present cohort, exploratory analyses failed to identify any genomic biomarkers differing significantly between responders and nonresponders (Table 1). Interestingly, 64% of evaluable patients harbored Wnt‐pathway gene alterations, and multivariate analysis suggests absence of Wnt alterations was associated with benefit, consistent with limited prior reports [28].

Notably, 45% of the patients here were enrolled in first‐line clinical trials, including 7 of 13 (54%) who received first‐line antiangiogenic therapy. In the exploratory analysis from the 1L phase III RAINFALL trial (cisplatin and 5‐fluorouraci + ramucirumab/placebo), there was a suggestion that more favorable OS was achieved in patients receiving 1L ram and subsequent ram‐containing therapy [33]. Within our limited dataset, there was no improved PFS or OS among patients receiving 1L therapy with antiangiogenic agents followed by FOLFIRI‐ram (data not shown). In fact, there was a trend toward inferior outcomes, although selection bias (more aggressive biology in 7/13 1L trial patients on antiangiogenic therapy) may confound this very small sample size.

There are several potential factors limiting the generalizability of our results, including the retrospective nature of our study. All patients received therapy at high‐volume GEA centers with multidisciplinary approaches, trial availability, and aggressive supportive care, which may contribute to improved outcomes [34]. Nearly all patients (89.6%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0–1 at the initiation of 2L FOLFIRI‐ram, and 45% were treated on a 1L clinical trial. However, poor prognostic features were well represented, with over 40% of patients with peritoneal disease, diffuse‐type disease, and/or ascites and 75.9% with poorly differentiated tumors. Indeed, in this cohort, diffuse‐type tumors had worse outcomes than nondiffuse type, confirming the negative prognostic connotation of diffuse‐type disease. The retrospective nature of our findings requires cautious interpretation, although the 1L features and outcomes are well aligned with prospective data, providing some validation for our findings.

Conclusion

We provide initial support for the safety and efficacy of 2L FOLFIRI‐ram after progression on 1L platinum/5FU in patients with GEA. To our knowledge, this represents the only existing data demonstrating favorable activity and safety in comparison with standard second‐line pac + ram. Our preliminary analysis highlights the importance of the ongoing phase II RAMIRIS trial examining FOLFIRI‐ram versus pac + ram in 2L GEA (NCT03081143). FOLFIRI‐ram may warrant consideration for inclusion as an alternate regimen in consensus guidelines for GEA.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

We recognize the important contributions from authors whose work could not be cited because of space constraints. This work was supported by the Howard H. Hall Fund for Esophageal Cancer Research (S.J.K.), ASCO Young Investigator Award, American Association for Cancer Research Gastric Cancer Fellowship, Paul Calabrese K12 (S.B.M.), NIH K23 award (CA178203‐01A1), University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center Award in Precision Oncology—Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA014599), Castle Foundation, Live Like Katie Foundation Award, Ullman Scholar Award, and the Sal Ferrara II Fund for PANGEA (D.V.T.C.).

Contributed equally

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Benjamin A. Weinberg, Joanne Xiu, Jimmy J. Hwang et al. Immuno‐Oncology Biomarkers for Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma: Why PD‐L1 Testing May Not Be Enough. The Oncologist 2018;23:1171–1177.

Implications for Practice: Pembrolizumab is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for patients with refractory gastric and gastroesophageal cancers if the tumor and adjacent tissue stain positively for the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) protein by companion diagnostic testing. Tumor mutational load, microsatellite instability (MSI), and alternative PD‐L1 testing thresholds may serve as predictive biomarkers for response to immune checkpoint inhibition, and standard PD‐L1 testing will not identify all patients who may benefit from this therapy.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Samuel J. Klempner, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Provision of study material or patients: Samuel J. Klempner, Steven B. Maron, Zev A. Wainberg, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Collection and/or assembly of data: Samuel J. Klempner, Steven B. Maron, Leah Chase, Samantha Lomnicki, Zev A. Wainberg, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Data analysis and interpretation: Samuel J. Klempner, Steven B. Maron, Leah Chase, Samantha Lomnicki, Zev A. Wainberg, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Manuscript writing: Samuel J. Klempner, Steven B. Maron, Leah Chase, Samantha Lomnicki, Zev A. Wainberg, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Final approval of manuscript: Samuel J. Klempner, Steven B. Maron, Leah Chase, Samantha Lomnicki, Zev A. Wainberg, Daniel V.T. Catenacci

Disclosures

Samuel J. Klempner: Foundation Medicine, Inc. (H); Astellas Pharma, Lilly Oncology (C/A); Merck, Leap Therapeutics, Incyte (institutional RF); Zev A. Wainberg: Genentech/Roche, Amgen, Eli Lilly & Co., Five Prime, EMD Serono, Bayer (RF); Daniel V.T. Catenacci: Lilly Oncology, Amgen, Taiho, Five Prime, Merck, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Astellas, Roche/Genentech, Foundation One, Guardant Health (C/A, SAB, H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lordick F, Lorenzen S, Yamada Y et al. Optimal chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: Is there a global consensus? Gastric Cancer 2014;17:213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Ann Oncol 2016;27(suppl 5):v38–v49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2‐positive advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess LM, Michael D, Mytelka DS et al. Chemotherapy treatment patterns, costs, and outcomes of patients with gastric cancer in the United States: A retrospective analysis of electronic medical record (EMR) and administrative claims data. Gastric Cancer 2016;19:607–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams T, Hess LM, Zhu YE et al. Predictors of heterogeneity in the first‐line treatment of patients with advanced/metastatic gastric cancer in the U.S. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): A double‐blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1224–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon HH, Bendell JC, Braiteh FS et al. Ramucirumab combined with FOLFOX as front‐line therapy for advanced esophageal, gastroesophageal junction, or gastric adenocarcinoma: A randomized, double‐blind, multicenter Phase II trial. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2196–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah MA, Bang YJ, Lordick F et al. Effect of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with or without onartuzumab in HER2‐negative, MET‐positive gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: The METGastric randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:620–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah MA, Janjigian YY, Stoller R et al. Randomized multicenter phase II study of modified docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (DCF) versus DCF plus growth factor support in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma: A study of the US Gastric Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3874–3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al‐Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection on survival in patients with limited metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: The AIO‐FLOT3 Trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1237–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al‐Batran SE, Hartmann JT, Hofheinz R et al. Biweekly fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) for patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction: A phase II trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1882–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang J, Gong J, Klempner SJ et al. Refining the management of resectable esophagogastric cancer: FLOT4, CRITICS, OE05, MAGIC‐B and the promise of molecular classification. J Gastrointest Oncol 2018;9:560–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: A French intergroup (Federation Francophone de Cancerologie Digestive, Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer, and Groupe Cooperateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie) study. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3520–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thuss‐Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second‐line chemotherapy in gastric cancer‐‐a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2306–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sagawa T, Satake H, Fujikawa K et al. Phase Ib study of ramucirumab and irinotecan for metastatic gastric cancer previously treated with fluoropyrimidine with/without platina and taxane. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 4):155a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second‐line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first‐line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): A randomised, double‐blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: Phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE‐059 trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e180013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waddell T, Chau I, Cunningham D et al. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for patients with previously untreated advanced oesophagogastric cancer (REAL3): A randomised, open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lordick F, Kang YK, Chung HC et al. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): A randomised, open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thuss‐Patience PC, Shah MA, Ohtsu A et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus taxane use for previously treated HER2‐positive locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GATSBY): An international randomised, open‐label, adaptive, phase 2/3 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:640–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shitara K, Özgüroğlu M, Bang YJ et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE‐061): A randomised, open‐label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;392:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shu Y, Zhang W, Hou Q et al. Prognostic significance of frequent CLDN18‐ARHGAP26/6 fusion in gastric signet‐ring cell cancer. Nat Commun 2018;9:2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maron SB, Alpert L, Kwak HA et al. Targeted therapies for targeted populations: Anti‐EGFR treatment for EGFR‐amplified gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2018;8:696–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pectasides E, Stachler MD, Derks S et al. Genomic heterogeneity as a barrier to precision medicine in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2018;8:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. PD‐1 Blockade in tumors with mismatch‐repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janjigian YY, Sanchez‐Vega F, Jonsson P et al. Genetic predictors of response to systemic therapy in esophagogastric cancer. Cancer Discov 2018;8:49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catenacci DVT, Tebbutt NC, Davidenko I et al. Rilotumumab plus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine as first‐line therapy in advanced MET‐positive gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction cancer (RILOMET‐1): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1467–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwak EL, Ahronian LG, Siravegna G et al. Molecular heterogeneity and receptor coamplification drive resistance to targeted therapy in MET‐amplified esophagogastric cancer. Cancer Discov 2015;5:1271–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali SM, Sanford EM, Klempner SJ et al. Prospective comprehensive genomic profiling of advanced gastric carcinoma cases reveals frequent clinically relevant genomic alterations and new routes for targeted therapies. The Oncologist 2015;20:499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabernero J, Hozak RR, Yoshino T et al. Analysis of angiogenesis biomarkers for ramucirumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer from RAISE, a global, randomized, double‐blind, phase III study. Ann Oncol 2018;29:602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shitara K, Shah MA, Di Bartolomeo M et al. Effect of post‐discontinuation therapy (PDT) on survival in metastatic gastric‐gastroesophageal junction (G‐GEJ) adenocarcinoma patients from the RAINFALL trial: An exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):4044a. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haj Mohammad N, Bernards N, van Putten M et al. Volume‐outcome relation in palliative systemic treatment of metastatic oesophagogastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2017;78:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]