Abstract

Lessons Learned.

Coadministration of S‐1 and paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer showed favorable efficacy.

Coadministration of S‐1 and paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced non‐small lung cancer showed tolerable toxicity.

Background.

Although monotherapy with cytotoxic agents including docetaxel or vinorelbine are recommended for elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the outcome is not satisfactory. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of S‐1 and paclitaxel (PTX) as a first‐line cotreatment in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

Methods.

Oral S‐1 was administered on days 1–14 every 3 weeks at 80, 100, and 120 mg per day for patients with body surface area < 1.25 m2, 1.25–1.5 m2, and > 1.5 m2, respectively. PTX was administered at 80 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8. The primary endpoint was response rate, and secondary endpoints were progression‐free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

Results.

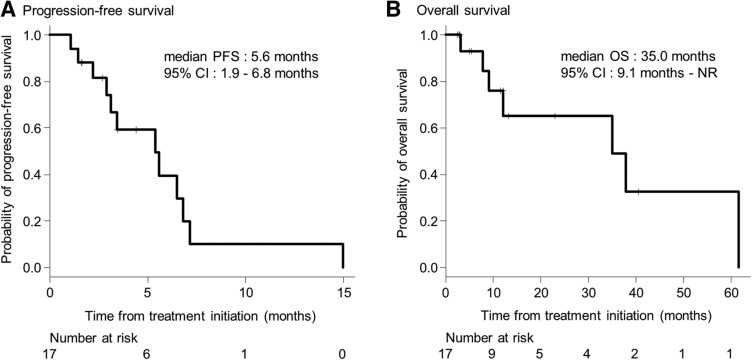

Seventeen patients were enrolled with response and disease control rates of 47.1% and 88.2%, respectively. Median PFS and OS were 5.6 and 35.0 months, respectively. Hematological grade 3 or 4 toxicities included leukopenia (55.8%), neutropenia (52.9%), febrile neutropenia (11.8%), and anemia (11.8%). Nonhematological grade 3 toxicities included stomatitis (23.5%), diarrhea (5.9%), and interstitial lung disease (5.9%), and grade 5 toxicities included interstitial lung disease (5.9%).

Conclusion.

This S‐1 and PTX cotherapy dose and schedule showed satisfactory efficacy with mild toxicities in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

Abstract

经验获取

• 在晚期非小细胞肺癌老年患者中同时使用 S‐1 和紫杉醇进行治疗显示出良好的疗效。

• 在晚期非小细胞肺癌老年患者中同时使用 S‐1 和紫杉醇进行治疗显示出可耐受的毒性。

摘要

背景。虽然晚期非小细胞肺癌 (NSCLC) 老年患者推荐采用含多西他赛或长春瑞滨的细胞毒制剂单药治疗,但是,预后并不令人满意。我们评估了将 S‐1 和紫杉醇(PTX)作为晚期 NSCLC 老年患者的一线联合治疗的有效性和安全性。

方法。在每 3 周的第 1–14 天,体表面积 < 1.25 m2、1.25–1.5 m2,以及 > 1.5 m2的患者分别按照每天 80 mg、100 mg 以及 120 mg 的剂量口服 S‐1。患者在第 1 天和第 8 天按照PTX 80 mg/m2 的剂量给药。主要终点为反应率,次要终点为无进展生存期 (PFS)、总生存期 (OS) 以及安全性。

结果。17 名入组患者的反应率和疾病控制率分别为 47.1% 和 88.2%。中位 PFS 和 OS 分别为 5.6 和 35.0 个月。3 或 4 级血液毒性包括白细胞减少症 (55.8%)、嗜中性粒细胞减少症 (52.9%)、发热性嗜中性粒细胞减少症 (11.8%) 以及贫血 (11.8%)。3 级非血液毒性包括口腔炎 (23.5%)、腹泻 (5.9%) 以及间质性肺病 (5.9%),5 级毒性包括间质性肺病 (5.9%)。

结论。本次 S‐1 和 PTX 协同治疗的剂量和时间表在晚期 NSCLC 老年患者中显示出令人满意的疗效以及轻微毒性。

Discussion

Coadministration of S‐1 and PTX is expected to be especially effective in patients with NSCLC with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, and four such patients included in this study showed prolonged survival in a subgroup analysis with a median OS of 49.8 months. In a pooled analysis of elderly patients with EGFR mutations, the median OS was 30.8 months [1]. Thus, the OS in our study was much longer than that reported previously, although our findings were obtained in a small sample in a subgroup analysis. Previous studies reported an inverse relationship between thymidylate synthase expression and fluorouracil (5‐FU) sensitivity in colorectal and gastric cancers [2], and the thymidylate synthase expression in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations has been reported to be significantly lower than that in wild‐type cases [3]. Moreover, thymidine phosphorylase converts 5‐FU to its more active form, fluorodeoxyuridylate, and a correlation between the expression of thymidine phosphorylase and efficacy of 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy has been observed [4]. Because PTX upregulated the expression of thymidine phosphorylase mRNA in human gastric cancer xenografts [5], we hypothesized that the combination of S‐1 with PTX would provide good anticancer effects.

In conclusion, cotherapy with S‐1 and PTX for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC showed favorable efficacy and tolerable toxicity. The results of this study met the criteria for the primary endpoint, suggesting that this regimen could be a treatment option for those patients. However, further studies are needed to compare this regimen with conventional therapy for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

Trial Information

- Disease

Lung cancer – NSCLC

- Stage of Disease/Treatment

Metastatic/advanced

- Prior Therapy

None

- Type of Study – 1

Phase II

- Type of Study – 2

Single arm

- Primary Endpoint

Overall response rate

- Secondary Endpoint

Progression‐free survival

- Secondary Endpoint

Overall survival

- Secondary Endpoint

Safety

- Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design

- The sample size was calculated at an α error of 0.05 and β error of 0.2. The expected response rate and threshold response rate are determined to be 35% and 10%, respectively. The estimated minimum sample size was 16, and considering the potential patient dropout, we planned to enroll 18 patients.

- Investigator's Analysis

Active and should be pursued further

Drug Information

- Drug 1

- Generic/Working Name

S‐1

- Company Name

Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

- Dose

40, 50, and 60 milligrams (mg) per squared meter (m2)

- Route

Oral (p.o.)

- Schedule of Administration

S‐1 was administered twice daily from day 1 to day 14. The dose of S‐1 was calculated according to the patient's body surface area as follows: 40, 50, and 60 mg/m2 S‐1 for body surface areas of <1.25, 1.25–1.50, and ≥ 1.50 m2, respectively.

- Drug 2

- Generic/Working Name

Paclitaxel

- Company Name

Bristol‐Myers Squibb

- Dose

PTX was fixed as 80 mg/m2

- Route

IV

- Schedule of Administration

PTX was fixed as 80 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8

Patient Characteristics

- Number of Patients, Male

13

- Number of Patients, Female

4

- Stage

IIIB or IV

- Age

Median (range): 79 (range, 72–84) years

- Number of Prior Systemic Therapies

Median (range): not collected

- Performance Status: ECOG

-

0 — 9

1 — 8

2 — 0

3 — 0

Unknown —

- Cancer Types or Histologic Subtypes

Adenocarcinoma, 8; squamous cell carcinoma, 5; non‐small cell lung carcinoma, 4.

Primary Assessment Method

- Title

Total patient population

- Number of Patients Enrolled

17

- Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity

17

- Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy

17

- Evaluation Method

RECIST 1.1

- Response Assessment – CR

n = 0 (0%)

- Response Assessment – PR

n = 8 (47.1%)

- Response Assessment – SD

n = 7 (41.2%)

- Response Assessment – PD

n = 2 (11.8%)

- (Median) Duration Assessments – PFS

5.6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–6.8

- (Median) Duration Assessments – OS

35.0 months; 95% CI, 9.1–NR

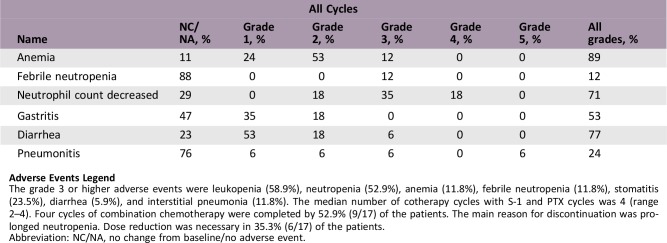

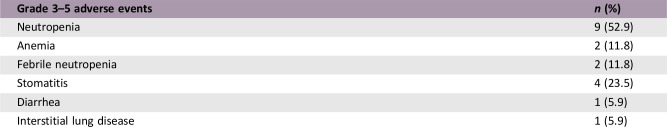

Adverse Events

Adverse Events Legend

The grade 3 or higher adverse events were leukopenia (58.9%), neutropenia (52.9%), anemia (11.8%), febrile neutropenia (11.8%), stomatitis (23.5%), diarrhea (5.9%), and interstitial pneumonia (11.8%). The median number of cotherapy cycles with S‐1 and PTX cycles was 4 (range 2–4). Four cycles of combination chemotherapy were completed by 52.9% (9/17) of the patients. The main reason for discontinuation was prolonged neutropenia. Dose reduction was necessary in 35.3% (6/17) of the patients.

Abbreviation: NC/NA, no change from baseline/no adverse event.

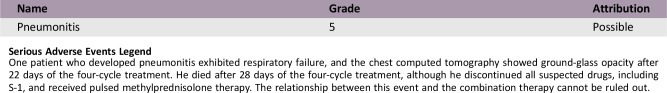

Serious Adverse Events

Serious Adverse Events Legend

One patient who developed pneumonitis exhibited respiratory failure, and the chest computed tomography showed ground‐glass opacity after 22 days of the four‐cycle treatment. He died after 28 days of the four‐cycle treatment, although he discontinued all suspected drugs, including S‐1, and received pulsed methylprednisolone therapy. The relationship between this event and the combination therapy cannot be ruled out.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

- Completion

Study completed

- Investigator's Assessment

Active and should be pursued further

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer‐related deaths worldwide, and the number of elderly patients with lung cancer is increasing [6]. Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of lung cancer cases, and nearly 50% of patients with NSCLC are aged ≥70 years [7]. Approximately 50% of patients with NSCLC show metastasis at diagnosis [8], and platinum doublet therapy is recommended for patients with advanced NSCLC with good performance status. However, although platinum doublet therapy is effective in some elderly patients, it may not show adequate efficacy in others because of an unfavorable side effect profile [9], [10].

For elderly patients with advanced NSCLC without driver oncogene mutation, monotherapy with cytotoxic agents such as docetaxel, vinorelbine, or gemcitabine (GEM) are recommended, but the efficacy of these regimens has not been satisfactory [11], [12], [13]. Therefore, these patients require a more effective and safe treatment approach. Although platinum‐based combination therapy has been shown to improve the overall response rate (ORR) and prolonged progression‐free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) more than monotherapy does, coadministration may be intolerable for elderly patients because of severe toxicities [9]. Therefore, for elderly patients, it is important to select drugs without platinum agents to obtain better effects with less toxicity.

S‐1 (Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) is an oral fluorinated pyrimidine formulation composed of tegafur, 5‐chloro‐2,4‐dihydroxy‐pyridine, a reversible inhibitor of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, and potassium oxonate. In a phase II study of elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, S‐1 monotherapy as a first‐line treatment was reported to be effective and well tolerated [14] with an ORR and median OS of 27.6% and 12.1 months and no grade 4 toxicity.

Paclitaxel (PTX; Bristol‐Myers Squibb, NY) is a microtubule‐stabilizing taxane drug. It enhances tubulin polymerization and inhibits spindle fiber function, resulting in inhibition of mitosis and cell division. Several phase II studies on the efficacy and safety of PTX monotherapy for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC have been reported, with ORRs of 23%–41.2% and median OS values of 9.8–10.3 months [15], [16]. However, for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, the combination of carboplatin and PTX was not significantly superior to PTX monotherapy and also showed more toxicity than the monotherapy did [9].

The combination of S‐1 and PTX is expected to show a greater synergistic effect than that of either drug alone. Thymidine phosphorylase (TP) converts fluorouracil (5‐FU) to fluorodeoxyuridylate, the more active metabolite. The efficacy of 5‐FU‐based anticancer agents is correlated with the expression of TP mRNA [4]. The expression levels of TP mRNA were upregulated by PTX in human gastric cancer xenografts [17], and significant tumor reduction was observed with PTX in combination with S‐1 in a mouse model of human breast cancer [18]. Moreover, some clinical studies have already reported that the combination of S‐1 and PTX is effective and tolerable for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC [19] as well as advanced gastric cancer [20], [21], [22].

We previously reported the results of a phase I study of S‐1 and PTX coadministration for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC [23]. We determined that the recommended dose of S‐1 and PTX was 80 mg/m2 during days 1–14 and days 1 and 8, respectively. In this study, we conducted a phase II study of S‐1 and PTX cotherapy for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

The results of this phase II study revealed that it met the criteria for the primary endpoint. The S‐1 and PTX cotherapy was the treatment option for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

Combination chemotherapy regimens, both platinum‐ and non‐platinum‐based, improve patient prognoses significantly compared with monotherapy [9], [24]. However, compared with non‐platinum‐based chemotherapy, platinum‐based chemotherapy shows severe toxicities in elderly patients [25]. Therefore, non‐platinum‐based combination chemotherapies are promising for the treatment of elderly patients. In fact, non‐platinum‐based cotherapy such as S‐1 plus GEM has been reported to be effective and well tolerated [26], [27].

Furthermore, previous studies have reported ORR, median PFS, and median OS of 27.0%–40.0%, 4.2– 6.4 months, and 12.9–17.8 months, respectively, in elderly patients who received cotherapy with S‐1 and GEM [26], [27], and these results were not superior to those of our study (Fig. 1). Therefore, cotherapy with S‐1 and PTX seemed to be effective and well tolerated. The results of this study indicate that it met the criteria for the primary endpoint of ORR. In this study, the patients received a combination of S‐1 and PTX and developed several adverse events, with hematological toxicities such as neutropenia occurring frequently. However, the rates of adverse events were similar to those with docetaxel monotherapy [28], which has been recommended for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC. Moreover, the reported grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities in elderly patients who received a combination of S‐1 with GEM were leukopenia (27.0%–29.0%), neutropenia (24.0%–45.9%), and anemia (0%–13.5%) [26], [27]. These results were equivalent to the findings of our study, indicating mild toxicities with S‐1 and PTX cotherapy.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier plots. (A): Kaplan‐Meier estimation of progression‐free survival. (B): Kaplan‐Meier estimation of overall survival.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; PFS, progression‐free survival.

Coadministration of S‐1 and PTX is expected to be especially effective in patients with NSCLC with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, and four such patients included in this study showed prolonged survival in a subgroup analysis with a median OS of 49.8 months. In a pooled analysis of elderly patients with EGFR mutations, the median OS was 30.8 months [1]. Thus, the OS in our study was much longer than that reported previously, although our findings were obtained for a small sample in a subgroup analysis.

Previous studies reported an inverse relationship between thymidylate synthase expression and 5‐FU sensitivity in colorectal and gastric cancers [2]. Thymidylate synthase expression in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations has been reported to be significantly lower than that in wild‐type cases, suggesting that tumors in these patients may show greater sensitivity [3]. Moreover, thymidine phosphorylase converts 5‐FU to its more active form, fluorodeoxyuridylate, and a correlation between the expression of thymidine phosphorylase and efficacy of 5‐FU‐based chemotherapy has been observed [4]. In several phase II studies, the S‐1 plus paclitaxel combination was effective and tolerated by patients with advanced gastric cancer [20], [21], [22], and a retrospective study by Aono et al. showed that S‐1 and paclitaxel combination therapy is effective for pretreated advanced NSCLC, with a response rate of 32.6% and median PFS of 253 days [19]. Because PTX upregulated the expression of thymidine phosphorylase mRNA in human gastric cancer xenografts [5], the combination of S‐1 with PTX would provide good anticancer effects.

In conclusion, coadministration of S‐1 and PTX for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC showed favorable efficacy and tolerable toxicity. The results of this study met the criteria for the primary endpoint, suggesting that this regimen could be a treatment option for those patients. However, further studies are needed to compare this regimen with conventional therapy for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

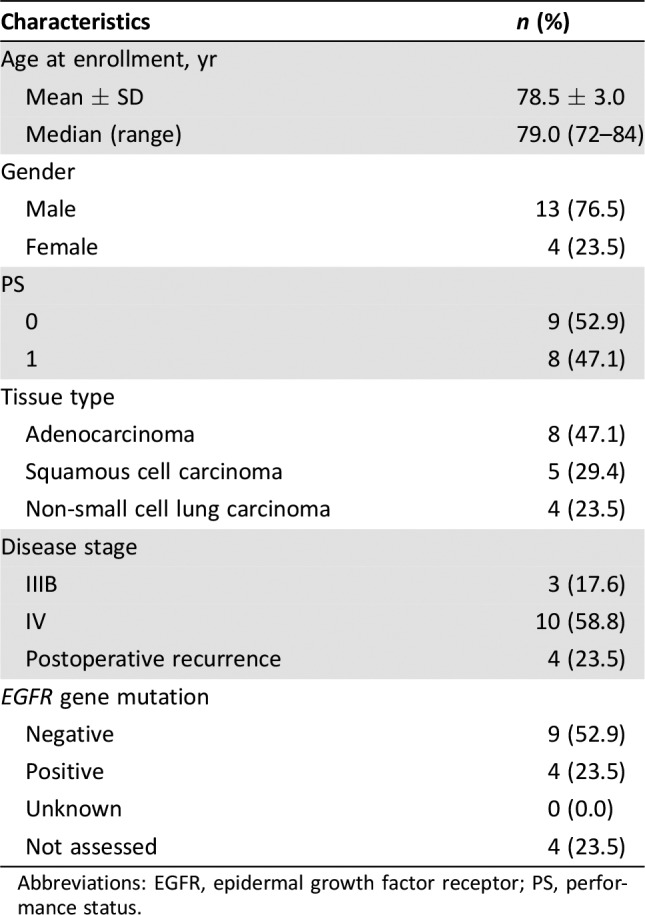

Table

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 17).

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; PS, performance status.

Contributed equally

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: UMIN000003782

Sponsor(s): Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine

Principal Investigator: Yoshinobu Iwasaki

IRB Approved: Yes

Disclosures

Junji Uchino: Eli Lilly Japan K.K. (RF); Koichi Takayama: Chugai‐Roche Co. and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. (RF), AstraZeneca, Chugai‐Roche Co., MSD‐Merck Co., Eli Lilly Co., Boehringer‐Ingelheim Co., Daiichi‐Sankyo Co. (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Morikawa N, Minegishi Y, Inoue A et al. First‐line gefitinib for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations. A combined analysis of North‐East Japan Study Group studies. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16:465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salonga D, Danenberg KD, Johnson M et al. Colorectal tumors responding to 5‐fluorouracil have low gene expression levels of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, thymidylate synthase, and thymidine phosphorylase. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren S, Chen X, Kuang P et al. Association of EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement with expression of DNA repair and synthesis genes in never‐smoker women with pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2012;118:5588–5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bruin M, van Capel T, Van der Born K et al. Role of platelet‐derived endothelial cell growth factor/thymidine phosphorylase in fluoropyrimidine sensitivity. Br J Cancer 2003;88:957–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai Y, Yoshida I, Kamoshida S et al. Changes of gene expression of thymidine phosphorylase, thymidylate synthase, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase after the administration of 5’‐deoxy‐5‐fluorouridine, paclitaxel and its combination in human gastric cancer xenografts. Anticancer Res 2008;28:1593–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provencio M, Camps C, Alberola V et al. Lung cancer and treatment in elderly patients: The Achilles Study. Lung Cancer 2009;66:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocher F, Hilbe W, Seeber A et al. Longitudinal analysis of 2293 NSCLC patients: A comprehensive study from the TYROL registry. Lung Cancer 2015;87:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP et al. Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: IFCT‐0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;378:1079–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe T, Takeda K, Ohe Y et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing weekly docetaxel plus cisplatin versus docetaxel monotherapy every 3 weeks in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: The intergroup trial JCOG0803/WJOG4307L. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudoh S, Takeda K, Nakagawa K et al. Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Trial (WJTOG 9904). J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3657–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Effects of vinorelbine on quality of life and survival of elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group . J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C et al. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: The Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y et al. Phase II study of S‐1 monotherapy as a first‐line treatment for elderly patients with advanced nonsmall‐cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2011;22:811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fidias P, Supko JG, Martins R et al. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2001;7:3942–3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura Y, Sekine I, Furuse K et al. Retrospective comparison of toxicity and efficacy in phase II trials of 3‐h infusions of paclitaxel for patients 70 years of age or older and patients under 70 years of age. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000;46:114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakurai Y, Yoshida I, Kamoshida S et al. Changes of gene expression of thymidine phosphorylase, thymidylate synthase, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase after the administration of 5’‐deoxy‐5‐fluorouridine, paclitaxel and its combination in human gastric cancer xenografts. Anticancer Res 2008;28:1593–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nukatsuka M, Fujioka A, Nakagawa F et al. Antimetastatic and anticancer activity of S‐1, a new oral dihydropyrimidine‐dehydrogenase‐inhibiting fluoropyrimidine, alone and in combination with paclitaxel in an orthotopically implanted human breast cancer model. Int J Oncol 2004;25:1531–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aono N, Ito Y, Nishino K et al. A retrospective study of the novel combination of paclitaxel and S1 for Pretreated advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Chemotherapy 2012;58:454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajo A, Hokita S, Ishigami S et al. A multicenter phase II study of biweekly paclitaxel and S‐1 combination chemotherapy for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2008;62:1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mochiki E, Ohno T, Kamiyama Y et al. Phase I/II study of S‐1 combined with paclitaxel in patients with unresectable and/or recurrent advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95:1642–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugimoto N, Narahara H, Sakai D et al. The effectiveness of S‐1 based sequential chemotherapy as second‐line treatment for advanced/recurrent gastric cancer [in Japanese]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2009;36:417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chihara Y, Date K, Takemura Y et al. Phase I study of S‐1 plus paclitaxel combination therapy as a first‐line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frasci G, Lorusso V, Panza N et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine alone in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2529–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos FN, de Castria TB, Cruz MR et al. Chemotherapy for advanced non‐small cell lung cancer in the elderly population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(10):CD010463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seto T, Yamanaka T, Wasada I et al. Phase I/II trial of gemcitabine plus oral TS‐1 in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: Thoracic Oncology Research Group study 0502. Lung Cancer 2010;69:213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaira K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N et al. Prospective exploratory study of gemcitabine and S‐1 against elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2017;14:1123–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudoh S, Takeda K, Nakagawa K et al. Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Trial (WJTOG 9904). J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3657–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]