Abstract

The (pro)renin receptor (PRR) is a new component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and regulates renin activity. The objective of the present study was to test potential roles of the renal PRR and intrarenal RAAS in the physiological status of late pregnancy. Late pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were studied 19–21 days after sperm was observed in vaginal smears. Experiments were performed using age-matched virgin rats and late pregnant rats treated with the specific PRR inhibitor PRO20 (700 μg·kg−1·day−1 sc for 14 days, 3 times/day for every 8 h) or vehicle. The indices of RAAS, including PRR, renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone levels, were examined by immunoblotting, qRT-PCR, or ELISA. Further analyses of renal epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) expression, sodium-water retention, and plasma volume were performed. We first present evidence for the activation of intrarenal RAAS in late pregnant rats, including increases in urinary renin activity, active and total renin content, and prorenin content, angiotensin II and aldosterone excretion, in parallel with increased renal PRR expression and urinary soluble PRR excretion. Functional evidence demonstrated that PRR antagonism with PRO20 effectively suppressed the indices of intrarenal RAAS in late pregnant rats. In addition, our results revealed that renal α-ENaC expression, sodium-water retention, and plasma volume were elevated during late pregnancy, which were all attenuated by PRO20. In summary, the present study examined the renal mechanism of sodium-water retention and plasma volume expansion in late pregnant rats and identified a novel role of PRR in regulation of intrarenal RAAS and α-ENaC and thus sodium and fluid retention associated with pregnancy.

Keywords: ENaC, plasma volume expansion, pregnancy, (pro)renin receptor, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is accompanied by marked changes in cardiovascular function, renal function, and fluid homeostasis. These adaptations permit an increase in blood volume that will supply the growing uterus and fetus without the development of maternal hypertension (32). Normal pregnancy is a state marked by avid sodium retention and plasma volume expansion. The sodium retention that occurs over the course of pregnancy mediates the increase in plasma volume that is needed for the developing uterus and fetus (32, 33). The gestational plasma volume expansion is a critical part of maternal remodeling, which accommodates the developing fetus during pregnancy. The fetus has a high metabolic rate and grows rapidly, requiring a high rate of delivery of substrates, including glucose, amino acids, electrolytes, and oxygen. Thus a high rate of placental blood flow is important for maintenance of substrate supply and fetal fluid balance (9).

Adequate levels of sodium are required to maintain the extracellular volume in pregnancy, which includes an expanded circulating blood volume and the demands of the conceptus for salt and water (19). The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) is a heteromultimeric channel made up of α-, β-, and γ-subunits, with the α-subunit being rate limiting for channel formation (12, 20). Increased renal α-ENaC protein contributes to the renal sodium retention and plasma volume expansion, which are required for a normal pregnancy (32, 33).

In 2002, Nguyen et al. (23) cloned a novel receptor for prorenin and renin, termed it the (pro)renin receptor (PRR), and assigned a renin-regulatory function to this receptor. Full-length PRR (fPRR) as a 39-kDa single transmembrane protein is cleaved by furin or site-1 protease to generate a 28-kDa N-terminal region, soluble PRR (sPRR), and a C-terminal transmembrane form (M8.9 complexed with V-ATPase) (7, 22). Both fPRR and sPRR are able to bind to renin and the inactive prorenin, thus enhancing the catalytic activity of renin, promoting the nonproteolytic activation of prorenin, and increasing the catalytic efficiency of local angiotensin II formation (24). PRO20 is a newly developed 21-amino acid PRR decoy peptide that interrupts the binding of renin/prorenin to PRR with high potency and specificity (16). Emerging evidence supports an important role of renal PRR in regulation of intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and renal function, particularly ENaC-dependent Na+ reabsorption and aquaporin-2 (AQP2)-dependent water transport in the collecting duct (CD) (18, 31, 35). Therefore, the overall goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that renal PRR was activated in the physiological status of late pregnant rats, resulting in the activation of intrarenal RAAS and upregulation of renal α-ENaC, thereby inducing sodium-water retention and plasma volume expansion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratories (Beijing, China). Pregnant rats were studied 19–21 days after sperm was observed in vaginal smears. Experiments were performed using age-matched virgin controls (CTR), normal late pregnant rats (Pregnancy), and normal late pregnant rats in combination with PRO20 treatment (700 μg·kg−1·day−1 sc for 14 days, 3 times/day for every 8 h; Pregnancy+PRO20). Rats were housed in metabolic cages in a temperature-controlled and humidity-controlled room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle for 24-h urine collection and to measure body weight (BW) and 24-h food and water intake. At the end of the experiment, rats were euthanized, and blood and kidneys were harvested. Urine and plasma electrolytes were determined with an automatic analyzer (9180 Electrolyte analyzer, Roche, Berlin, Germany). Rats were allowed free access to standard chow (NaCl: 0.5%) and water. The animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China).

Renin activity assay.

A renin activity assay was performed as previously described (36). Briefly, renin activity in urine was determined by the delta value of angiotensin I generation using an ELISA kit from the sample incubating at 4°C and 37°C for 1 h, respectively. Total renin content was measured with excessive angiotensinogen plus trypsinization, and active renin content with excessive angiotensinogen. Urine samples were spiked with 1 μM synthetic renin substrate tetradecapeptide (RST, R8129; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After incubation at 37°C for 18 h, angiotensin I generation was assayed by using an angiotensin I ELISA kit (S-1188; Peninsula Laboratories International, San Carlos, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The values were expressed as nanograms per milliliter per hour of generated angiotensin I. For measurement of total renin content, trypsinization was performed to activate prorenin to renin (30, 35). The samples were incubated with trypsin derived from bovine pancreas (100 g/l, T1426; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 18 h. The reaction was then terminated with soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 g/l, T6522; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 1 h.

qRT-PCR.

Snap-frozen renal samples were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (cat. no. 15596018; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA isolation and RT were performed as previously described (36). Total RNA concentrations were determined using a NANODROP 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We used 1 μg of total RNA as a template for RT by using a Transcriptor first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (cat. no. 04379012001; Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using the ABI Prism StepOnePlus System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) and a SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Tli RNaseH Plus; cat. no. DRR420A; Takara, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequences of oligonucleotides primers (5′→3′) are shown as follows: renin: (F) GATCACCATGAAGGGGGTCTCTGT and (R) GTTCCTGAAGGGATTCTTTTGCAC; and GAPDH: (F) GTCTTCACTACCATGGAGAAGG and (R) TCATGGATGACCTTGGCCAG (35). All reactions were run in duplicate. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated from threshold cycle numbers (CT), i.e., 2−ΔΔCT, according to the manufacturer’s suggestion. The data were shown as a relative value normalized by GAPDH.

Immunoblot analysis.

Tissue samples from the renal cortex and inner medulla were lysed and subsequently sonicated in RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) with protease inhibitor cocktail (REF 04693116001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentrations were determined with the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo, Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As previously described (36), to verify linearity of the detection system, one-half of the protein amount was loaded to verify doubling of signal intensity; to verify uniform loading, loading gels were run, and random bands were quantified. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (PRR, 1:1,000 dilution, HPA003156, Sigma-Aldrich; α-ENaC: 1:1,000 dilution, SPC-403D, StressMarq; β-ENaC: 1:1,000 dilution, SPC-404D, StressMarq; γ-ENaC: 1:1,000 dilution, SPC-405D, StressMarq; β-actin: 1:10,000 dilution, A-2066, Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in antibody dilution buffer (1.5 g BSA, 0.1 g NaN3, 50 ml TBST) overnight at 4°C. After being washed with TBST, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies goat anti-rabbit/mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific). Signals on immunoblots were detected using a Tanon 5200 Luminescent Imaging Workstation (Tanon, Shanghai, China) and quantitated using Image-Pro Plus version 6.0 software. The expression of protein was calculated in relation to β-actin.

Immunofluorescence.

The tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization, thin sections (4 μm) were processed for labeling with immunofluorescence. The slides were blocked in 1% BSA for 1 h and were then incubated with primary antibody (PRR, 1:200 dilution, ab40790, Abcam) at 4°C overnight. After washing off of the primary antibody, sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with donkey anti-rabbit IgG-TRITC (1:100, Life Technologies). After washing off of the secondary antibody, images were captured using a Leica DMI4000B fluorescence microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) (35). The relative fluorescence intensity of all immunofluorescence images were evaluated by semiquantitative statistical analysis as previously described (11, 13, 37). In brief, we analyzed the fluorescence intensity of each image by using ImageJ software (Image Processing and Analysis in Java, National Institutes of Health). To assess the relative changes in fluorescence intensity, the fluorescence intensity of each image was normalized with the average fluorescence intensity of the CTR group.

ELISA assays for total renin/prorenin, sPRR, angiotensin II, and aldosterone.

Total renin/prorenin, sPRR, angiotensin II, and aldosterone levels, released into the plasma and urine, were measured by using a total rat renin/prorenin ELISA kit (RPRENKT-TOT, Molecular Innovations, Novi); sPRR assay kit (cat. no. 27782; Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan); angiotensin II ELISA kit (ADI-900–204; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) and aldosterone ELISA kit (cat. no. 10004377; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hematocrit measurement.

Hematocrit (Hct) was measured at the end of the experiment. Hct measurement was performed as previously described (38). The saphenous vein was punctured using a 23-gauge needle, and one drop of blood (5–10 μl) was collected by using a 10-μl capillary glass. One side of the tube was sealed with Hemato-Seal and then centrifuged for 2 min in a Thermo IEC (Boston, MA) microcentrifuge machine.

Plasma volume determination.

Plasma volume determination was performed as previously described (2). Under general anesthesia with isoflurane (2 ml/min), 0.2 ml of 2 mg/ml FITC-Dextran 500000-Conjugate (FITC-d; 46947–100MG-F, Sigma) was injected into the jugular vein. Seven minutes later, blood was withdrawn from the vena cava. Plasma was separated by centrifugation of the blood at 4,000 rpm for 10 min in the dark. Fluorescence levels were measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm (FLUOstar Omega Microplate Reader-BMG LABTECH), and FITC-d concentration/ml of plasma was calculated based on a standard curve generated by a serial dilution of the 2 mg/ml FITC-d solution. The standard curve was linear and highly reproducible. The plasma volume data were shown as a relative value normalized by BW.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Significance was accepted when P < 0.05. A test to determine normality of distribution for each data set was performed by GraphPad Prism software. For comparison among three or more mean values, if the data were distributed normally, a one-way ANOVA was performed to determine whether significant differences existed among groups. If significance was obtained, a Tukey’s post hoc test was used to identify the location of the differences. If the data were not distributed normally, a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was performed. If significance was obtained, a Dunn’s post hoc test was used to identify the location of the differences. For comparison among two mean values, a paired or unpaired t-test was performed as appropriate (4).

RESULTS

Renal PRR is increased during normal late pregnancy.

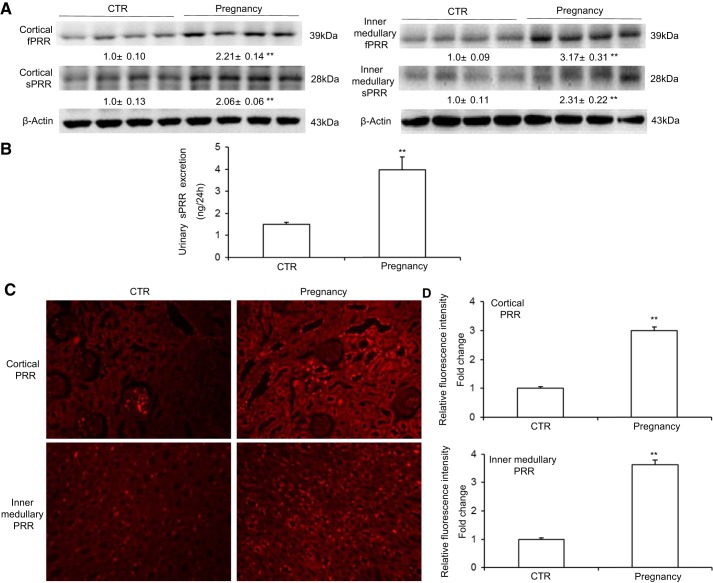

In our study, immunoblotting analysis demonstrated that protein abundances of fPRR and sPRR in the renal cortex and inner medulla (Fig. 1A) were all elevated in the late pregnant rats (Pregnancy) group compared with the age-matched virgin controls (CTR). In contrast, the expression of neither fPRR nor sPRR in the renal outer medulla was altered in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR. ELISA detected a similar increase in urinary sPRR excretion in the pregnant rats (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence staining supported these data; i.e., the expressions of PRR in the renal cortex and inner medulla were both increased in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR (Fig. 1, C and D). These results represent evidence of activation of renal PRR during normal late pregnancy.

Fig. 1.

Renal (pro)renin receptor (PRR) expression is increased during normal late pregnancy. A: representative immunoblotting and densitometric analysis of full-length (fPRR) and soluble (sPRR) PRR protein in the renal cortex and renal inner medulla. The densitometry values are shown underneath the corresponding blots. Expression was normalized by β-actin; n = 8–12/group. B: ELISA measurement of urinary sPRR excretion; n = 8–12/group. C: representative immunofluorescence images of cortical and inner medullary PRR in control (CTR) and Pregnancy group rats. D: statistical results of semiquantitative analysis for the relative fluorescence intensity of all immunofluorescence images; n = 6/group. Values are means ± SE. **P < 0.01 vs. CTR.

Renal PRR regulates intrarenal RAAS in late pregnancy.

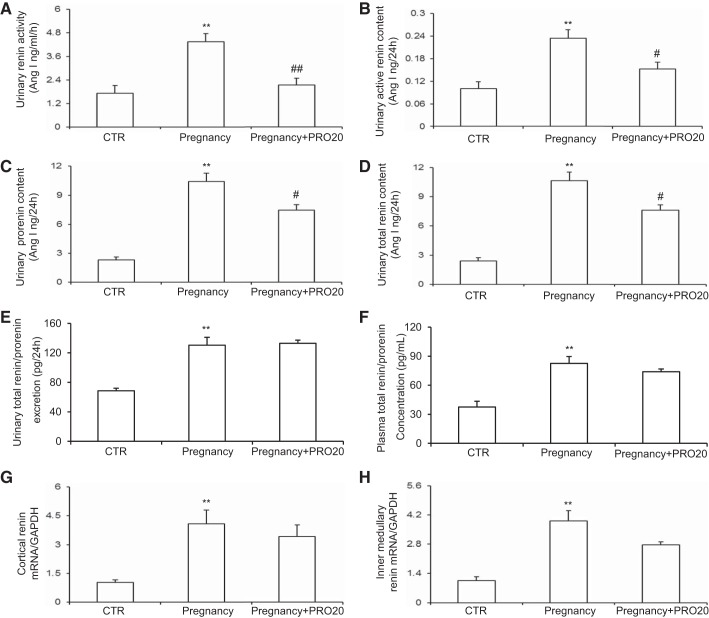

The urinary renin activity (Fig. 2A), active renin content (Fig. 2B), prorenin content (Fig. 2C), and total renin content (Fig. 2D) were all elevated during normal late pregnancy, which were all attenuated by PRO20 treatment. ELISA showed that urinary total renin/prorenin excretion (Fig. 2E) and plasma total renin/prorenin concentration (Fig. 2F) were elevated but were unaffected by PRO20, and the same result was obtained by qRT-PCR of renin mRNA (Fig. 2, G and H). Of note, the ELISA kit was unable to differentiate between prorenin and renin.

Fig. 2.

Renal PRR primarily increases intrarenal renin activity but not renin expression during normal late pregnancy. The urine samples were assayed for urinary renin activity (A), urinary active renin content (B), urinary prorenin content (C), and urinary total renin content (D). The urine samples (E) and plasma samples (F) were assayed for total renin/prorenin by ELISA. Of note, the ELISA kit was unable to differentiate between prorenin and renin. qRT-PCR was performed to analyze renin mRNA expression in the renal cortex (G) and renal inner medulla (H); n = 8–to 12/group. **P < 0.01 vs. CTR. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. Pregnancy.

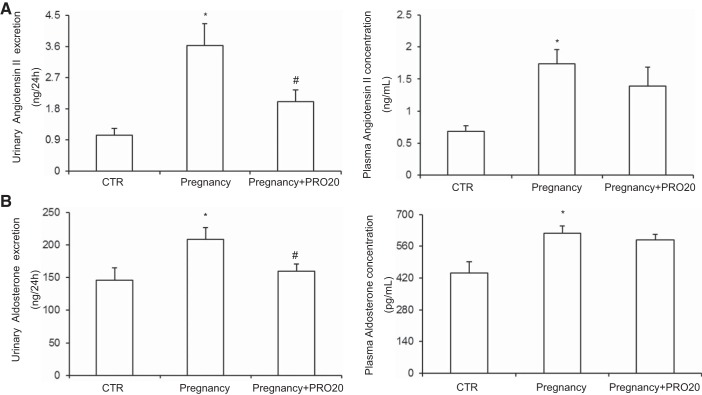

A large number of previous studies have shown that some components of RAAS are elevated in the plasma during pregnancy (15, 19, 29). We found that sPRR, angiotensin II, and aldosterone levels in plasma were increased during late pregnancy, which were consistent with the existing literature. Furthermore, our study first found that urinary sPRR, angiotensin II, and aldosterone excretion were augmented during late pregnancy, which illustrated that intrarenal RAAS was activated during late pregnancy. PRR has recently shown to be a key regulator of intrarenal RAAS (30, 35). We therefore examined the possibility that PRR may control the activity of intrarenal RAAS during late pregnancy. In support of this possibility, we found that PRR antagonism with PRO20 only reduced urinary angiotensin II and aldosterone excretion but not plasma angiotensin II and aldosterone levels (Fig. 3, A and B). These results show that the activation of intrarenal RAAS is dependent on renal PRR during late pregnancy, which is independent of circulating RAAS.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of other renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) components. A: ELISA measurement of urinary angiotensin II excretion and plasma angiotensin II concentration. B: ELISA measurement of urinary aldosterone excretion and plasma aldosterone concentration; n = 8– to 12/group. *P < 0.05 vs. CTR. #P < 0.05 vs. Pregnancy.

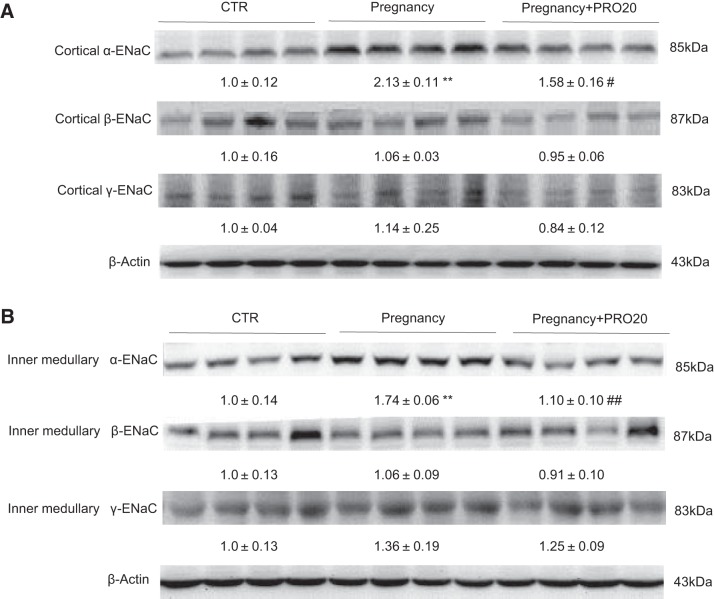

PRR mediates pregnancy-induced renal α-ENaC expression.

Adequate level of sodium is necessary for maintaining pregnancy-mediated plasma volume expansion. To explore the function of PRR in regulating sodium balance, we tested renal ENaC expression by immunoblotting. The result revealed that α-ENaC expressions in the renal cortex (Fig. 4A) and inner medulla (Fig. 4B) were both elevated in the Pregnancy group compared with CTR, which were attenuated by PRO20 treatment. In contrast, the β-ENaC and γ-ENaC protein abundances in the renal cortex (Fig. 4A) and inner medulla (Fig. 4B) were unchanged, consistent with the previous report (32). This result suggests a stimulatory effect of PRR on renal α-ENaC expression during normal late pregnancy.

Fig. 4.

Effect of PRO20 on renal epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) expression in normal late pregnant rats. Representative immunoblot and densitometric analysis of α-ENaC, β-ENaC, and γ-ENaC protein in the renal cortex (A) and renal inner medulla (B) are shown. The densitometry values are shown underneath the corresponding blots. Expression was normalized by β-actin; n = 8–12/group. Data are means ± SE. **P < 0.01 vs. CTR. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. Pregnancy.

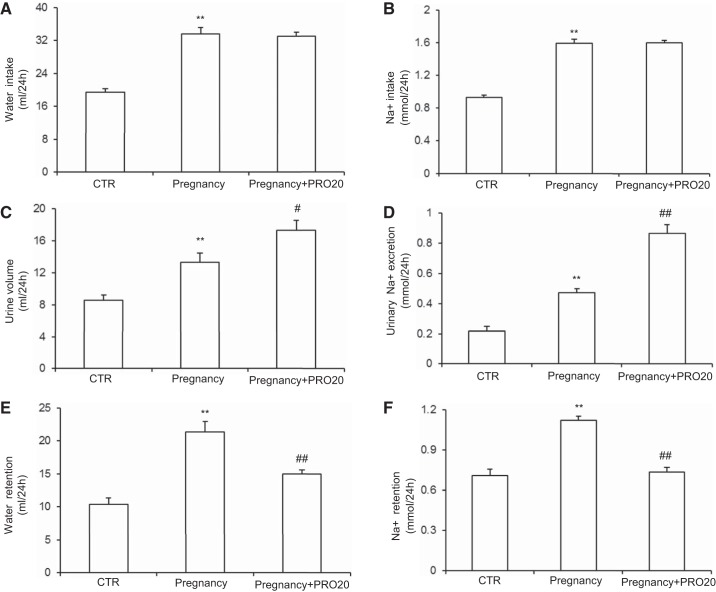

Renal PRR mediates pregnancy-induced sodium-water retention.

To explore the function of PRR in regulating water retention and sodium retention during pregnancy, we analyzed physiological data from the metabolic cage experiment. The Pregnancy and Pregnancy+PRO20 groups both exhibited significant increases in water intake (Fig. 5A) and Na+ intake (Fig. 5B) compared with CTR. There were no differences in water intake (Fig. 5A) and Na+ intake (Fig. 5B) between the Pregnancy and Pregnancy+PRO20 groups. Similarly, the urine volume (Fig. 5C) and urinary Na+ excretion (Fig. 5D) were increased in Pregnancy group rats compared with CTR. Compared with the Pregnancy group, urine volume (Fig. 5C) and urinary Na+ excretion (Fig. 5D) were further increased in the Pregnancy+PRO20 group. As a result, water retention (Fig. 5E) and Na+ retention (Fig. 5F) were both increased in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR, which were both attenuated by PRO20 treatment. These results support a partial but significant role of PRR in mediating pregnancy-induced sodium-water retention.

Fig. 5.

Summary of physiological data from metabolic cage experiment of CTR, Pregnancy group, and Pregnancy+PRO20 group. A: water intake. B: Na+ intake. C: urine volume. D: urinary Na+ excretion. E: water retention. F: Na+ retention; n = 8–12/group. **P < 0.01 vs. CTR. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 vs. Pregnancy.

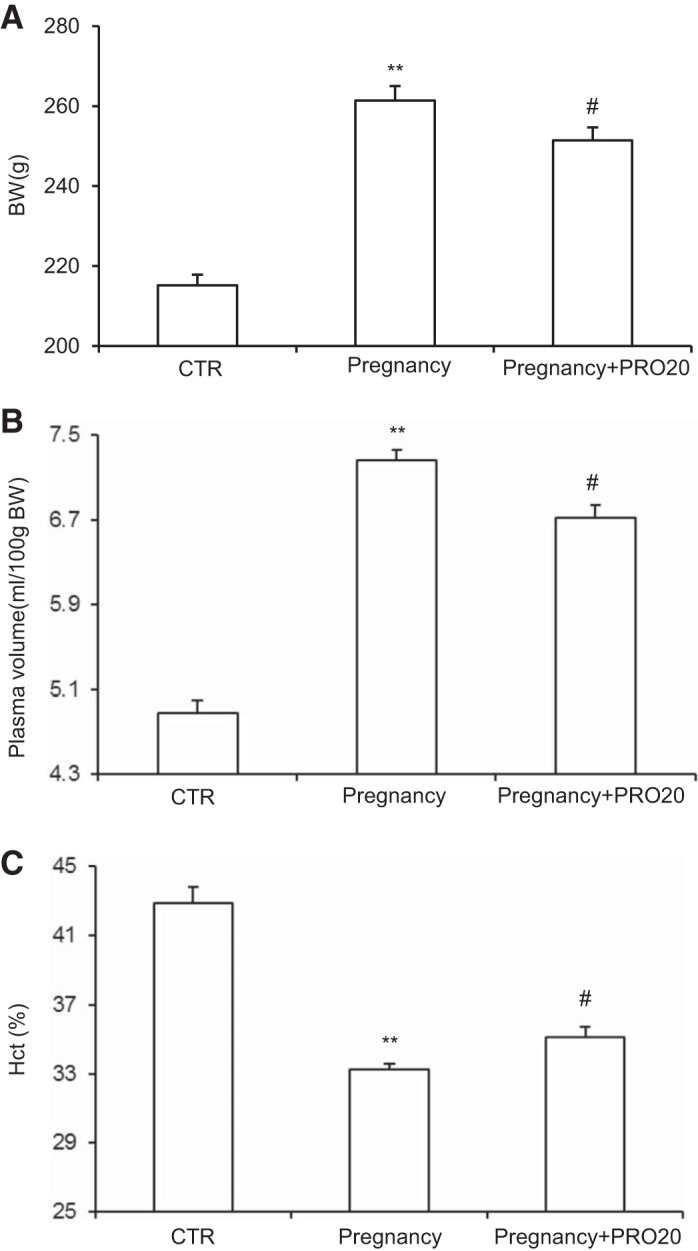

Renal PRR mediates pregnancy-induced plasma volume expansion.

Pregnancy induces weight gain as a result of fluid retention and plasma volume expansion. BW was increased in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR, which was attenuated by PRO20 treatment (Fig. 6A). By using a FITC-dextran 500000-conjugate, we performed direct measurement of plasma volume. Expansion of plasma volume was observed in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR, which was attenuated by PRO20 treatment (Fig. 6B). Since pregnancy has no effect on erythropoiesis, the change in Hct has been used as a surrogate marker of pregnancy-induced plasma volume expansion. Consistent with the plasma volume data, Hct was decreased in the Pregnancy group compared with the CTR, which was attenuated by PRO20 (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that the activation of renal PRR contributes to pregnancy-induced plasma volume expansion in late pregnant rats.

Fig. 6.

A: effect of PRO20 on body weight (BW) in normal late pregnant rats. B: effect of PRO20 on plasma volume in normal late pregnant rats. C: effect of PRO20 on hematocrit (Hct) in normal late pregnant rats; n = 8–12/group. **P < 0.01 vs. CTR. #P < 0.05 vs. Pregnancy.

DISCUSSION

The levels of plasma RAAS components in normotensive pregnant women are increased except for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) (21). Angiotensinogen synthesis by the liver is increased by circulating estrogen produced by the growing placenta. This leads to increased plasma angiotensin II and aldosterone levels (5, 19). There are many studies indicating that circulating RAAS plays an important role in salt balance and the subsequent well-being of mother and fetus (15, 19, 27, 34). Meanwhile, the intrarenal RAAS has also been shown to contribute to the sodium retention and plasma volume expansion during pregnancy (26). However, whether intrarenal RAAS changes during normal late pregnancy, and how it contributes to the changes in renal function to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance, are unknown. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to test potential roles of renal PRR, a new regulator of the intrarenal RAAS, during normal late pregnancy.

In our study, immunoblot analysis and immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that renal PRR was elevated in late pregnant rats, and so was urinary sPRR, as detected by using ELISA. In vitro evidence originally demonstrated that PRR binding to prorenin or renin leads to enhanced angiotensin I generation, suggesting that PRR-dependent renin regulation may primarily occur at the activity level. In support of this notion, we have previously shown that PRR antagonism with PRO20 only reduces renin activity in the kidney and urine but not renin mRNA during angiotensin II-induced hypertension (30). In accordance with that, our study showed that PRO20 suppressed intrarenal renin at the levels of activity but not expression.

A series of our previous studies have shown that the renal PRR and intrarenal RAAS play an important role in pathogenesis of angiotensin II–induced hypertension, high fructose-induced salt sensitivity, and albumin overload-induced nephropathy (10, 30, 35). Consistent with this notion, we first present evidence for overactivation of the intrarenal RAAS in late pregnant rats, as evidenced by increases in urinary renin activity, active and total renin content, and prorenin content, angiotensin II and aldosterone excretion, in parallel with increased renal PRR expression and urinary sPRR excretion. Functional evidence demonstrated that PRR antagonism with PRO20 effectively suppressed the indices of intrarenal RAAS in late pregnant rats. These results support the association of renal PRR and intrarenal RAAS in the current experimental model. Moreover, PRO20 only decreased urinary angiotensin II and aldosterone excretion but not plasma angiotensin II and aldosterone concentration. These results show that the activation of intrarenal RAAS is dependent on renal PRR during late pregnancy, which is likely independent of circulating RAAS. Besides intrarenal RAAS, circulating RAAS is also activated during pregnancy, as evidenced by increased plasma prorenin, renin, angiotensinogen, and plasma renin activity in pregnant women. In particular, normal pregnancy in humans is associated with a fivefold increase in plasma inactive renin (prorenin), which is much greater than that in plasma active renin (8, 14). Moreover, the increased circulating prorenin during early pregnancy is derived from the ovary (8). The relative importance of circulating vs. intrarenal RAAS is unknown and warrants further investigation.

During late pregnancy, the renal sodium-water retention and plasma volume expansion are at the highest level (1). Maternal cardiovascular and renal function are profoundly altered by the presence of a conceptus (1). There is marked vasodilation and an increase in blood flow, particularly to the kidney, presumably in response to metabolic demand and to eliminate the waste products of metabolism, which leads to the rise in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (6). However, the rise in GFR would result in an increase in the amount of urine volume and urinary sodium excretion, unless there is a compensatory increase in RAAS-mediated sodium reabsorption (19). Thus the activated RAAS plays an extremely important role in renal sodium reabsorption, sodium-water retention, and plasma volume expansion during pregnancy (20, 28, 33).

The enhanced ENaC-mediated sodium reabsorption in the maintenance of plasma volume expansion during late pregnancy is very significant. According to existing literature reports, the only increased renal sodium channel protein during late pregnancy was the α-ENaC (32, 33), which were consistent with our research results. The renal α-ENaC is necessary for maintaining pregnancy-mediated sodium-water retention and plasma volume expansion (33). Our result revealed that renal α-ENaC protein was elevated during late pregnancy, which was attenuated by PRO20. This result suggests that PRR mediates pregnancy-induced renal α-ENaC upregulation. The mechanism for the activation of α-ENaC by PRR during late pregnancy remains elusive. We speculate that PRR-dependent activation of intrarenal RAAS may mediate the upregulation of the α-ENaC. In support of this possibility, both prorenin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone can activate α-ENaC (3, 17, 20, 25). Overall, renal PRR may mediate pregnancy-induced renal α-ENaC upregulation via activation of intrarenal RAAS. As a result of all of this, PRO20 could decrease sodium reabsorption to promote urinary sodium excretion and increase urine volume. Therefore, the sodium-water retention during late pregnancy could be relieved by PRO20. Owing to sodium-water retention, the Hct was decreased and the BW and plasma volume were increased in late pregnant rats. Consistent with these results, the changes in Hct, BW, and plasma volume during late pregnancy were all attenuated by PRO20. Therefore, PRO20 can inhibit α-ENaC to decrease sodium reabsorption and promote sodium-water excretion by blocking the activation of renal PRR and intrarenal RAAS.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that renal PRR plays an important role in the physiological status of late pregnancy. We present strong evidence for the activation of renal PRR and intrarenal RAAS during late pregnancy. Meanwhile, administration of PRR decoy inhibitor PRO20 attenuates pregnancy-induced α-ENaC upregulation, sodium-water retention, and plasma volume expansion associated with suppressed intrarenal RAAS. Taken together, our data examined the renal mechanism of pregnancy-induced sodium-water retention and plasma volume expansion in rats. The mechanism involved PRR-dependent activation of intrarenal RAAS and stimulation of α-ENaC.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 91439205, 31330037, and 81630013; National Institutes of Health Grants DK104072, DK094956, and HL135851; and Merit Review 5I01BX002817 from the Department of Veterans Affairs. T. Yang is a Research Career Scientist in the Department of Veterans Affairs.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.F. and T.Y. conceived and designed research; Z.F., J.H., L.Z., Y.C., M.D., X.L., J.S., and A.L. performed experiments; Z.F., J.H., L.Z., Y.C., M.D., X.L., J.S., and A.L. analyzed data; Z.F., J.H., L.Z., X.F. and T.Y. interpreted results of experiments; Z.F. prepared figures; Z.F. drafted manuscript; Z.F., X.F. and T.Y. edited and revised manuscript; Z.F. and T.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander EA, Churchill S, Bengele HH. Renal hemodynamics and volume homeostasis during pregnancy in the rat. Kidney Int 18: 173–178, 1980. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron WM, Stamoutsos BA, Lindheimer MD. Role of volume in the regulation of vasopressin secretion during pregnancy in the rat. J Clin Invest 73: 923–932, 1984. doi: 10.1172/JCI111316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beutler KT, Masilamani S, Turban S, Nielsen J, Brooks HL, Ageloff S, Fenton RA, Packer RK, Knepper MA. Long-term regulation of ENaC expression in kidney by angiotensin II. Hypertension 41: 1143–1150, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000066129.12106.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharath LP, Cho JM, Park SK, Ruan T, Li Y, Mueller R, Bean T, Reese V, Richardson RS, Cai J, Sargsyan A, Pires K, Anandh Babu PV, Boudina S, Graham TE, Symons JD. Endothelial cell autophagy maintains shear stress-induced nitric oxide generation via glycolysis-dependent purinergic signaling to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 37: 1646–1656, 2017. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MA, Gallery ED, Ross MR, Esber RP. Sodium excretion in normal and hypertensive pregnancy: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 159: 297–307, 1988. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(88)80071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung KL, Lafayette RA. Renal physiology of pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 20: 209–214, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousin C, Bracquart D, Contrepas A, Corvol P, Muller L, Nguyen G. Soluble form of the (pro)renin receptor generated by intracellular cleavage by furin is secreted in plasma. Hypertension 53: 1077–1082, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derkx FH, Alberda AT, de Jong FH, Zeilmaker FH, Makovitz JW, Schalekamp MA. Source of plasma prorenin in early and late pregnancy: observations in a patient with primary ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 65: 349–354, 1987. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-2-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimasuay KG, Boeuf P, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental responses to changes in the maternal environment determine fetal growth. Front Physiol 7: 12, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang H, Deng M, Zhang L, Lu A, Su J, Xu C, Zhou L, Wang L, Ou JS, Wang W, Yang T. Role of (pro)renin receptor in albumin overload-induced nephropathy in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 315: 1759-1768, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00071.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontenete S, Carvalho D, Lourenço A, Guimarães N, Madureira P, Figueiredo C, Azevedo NF. FISHji: new ImageJ macros for the quantification of fluorescence in epifluorescence images. Biochem Eng J 112: 61–69, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure, and regulation. Physiol Rev 77: 359–396, 1997. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartig SM. Basic image analysis and manipulation in ImageJ. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 102: 14.15.1–14.15.12, 2013. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1415s102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsueh WA, Luetscher JA, Carlson EJ, Grislis G, Fraze E, McHargue A. Changes in active and inactive renin throughout pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 54: 1010–1016, 1982. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-5-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irani RA, Xia Y. The functional role of the renin-angiotensin system in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Placenta 29: 763–771, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li W, Sullivan MN, Zhang S, Worker CJ, Xiong Z, Speth RC, Feng Y. Intracerebroventricular infusion of the (Pro)renin receptor antagonist PRO20 attenuates deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt-induced hypertension. Hypertension 65: 352–361, 2015. [Erratum in Hypertension 70: e33, 2017]. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X, Wang F, Liu M, Yang KT, Nau A, Kohan DE, Reese V, Richardson RS, Yang T. Activation of ENaC in collecting duct cells by prorenin and its receptor PRR: involvement of Nox4-derived hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F1243–F1250, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00492.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X, Wang F, Xu C, Soodvilai S, Peng K, Su J, Zhao L, Yang KT, Feng Y, Zhou S-F, Gustafsson J-Å, Yang T. Soluble (pro)renin receptor via β-catenin enhances urine concentration capability as a target of liver X receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E1898–E1906, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602397113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumbers ER, Pringle KG. Roles of the circulating renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in human pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R91–R101, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00034.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May A, Puoti A, Gaeggeler HP, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Early effect of aldosterone on the rate of synthesis of the epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit in A6 renal cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1813–1822, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrill DC, Karoly M, Chen K, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Angiotensin-(1-7) in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Endocrine 18: 239–245, 2002. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:18:3:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa T, Suzuki-Nakagawa C, Watanabe A, Asami E, Matsumoto M, Nakano M, Ebihara A, Uddin MN, Suzuki F. Site-1 protease is required for the generation of soluble (pro)renin receptor. J Biochem 161: 369–379, 2017. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen G. Renin, (pro)renin and receptor: an update. Clin Sci (Lond) 120: 169–178, 2011. doi: 10.1042/CS20100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen G, Delarue F, Burcklé C, Bouzhir L, Giller T, Sraer JD. Pivotal role of the renin/prorenin receptor in angiotensin II production and cellular responses to renin. J Clin Invest 109: 1417–1427, 2002. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng K, Lu X, Wang F, Nau A, Chen R, Zhou SF, Yang T. Collecting duct (pro)renin receptor targets ENaC to mediate angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F245–F253, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00178.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pringle KG, de Meaultsart CC, Sykes SD, Weatherall LJ, Keogh L, Clausen DC, Dekker GA, Smith R, Roberts CT, Rae KM, Lumbers ER. Urinary angiotensinogen excretion in Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnant women. Pregnancy Hypertens 12: 110–117, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah DM. The role of RAS in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep 8: 144–152, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todkar A, Di Chiara M, Loffing-Cueni D, Bettoni C, Mohaupt M, Loffing J, Wagner CA. Aldosterone deficiency adversely affects pregnancy outcome in mice. Pflügers Arch 464: 331–343, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verdonk K, Visser W, Van Den Meiracker AH, Danser AH. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in pre-eclampsia: the delicate balance between good and bad. Clin Sci (Lond) 126: 537–544, 2014. doi: 10.1042/CS20130455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang F, Lu X, Liu M, Feng Y, Zhou S-F, Yang T. Renal medullary (pro)renin receptor contributes to angiotensin II-induced hypertension in rats via activation of the local renin-angiotensin system. BMC Med 13: 278, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0514-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang F, Lu X, Peng K, Fang H, Zhou L, Su J, Nau A, Yang KT, Ichihara A, Lu A, Zhou SF, Yang T. Antidiuretic action of collecting duct (pro)renin receptor downstream of vasopressin and PGE2 receptor EP4. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3022–3034, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West C, Zhang Z, Ecker G, Masilamani SM. Increased renal alpha-epithelial sodium channel (ENAC) protein and increased ENAC activity in normal pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R1326–R1332, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00082.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West CA, Han W, Li N, Masilamani SM. Renal epithelial sodium channel is critical for blood pressure maintenance and sodium balance in the normal late pregnant rat. Exp Physiol 99: 816–823, 2014. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.076273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West CA, Sasser JM, Baylis C. The enigma of continual plasma volume expansion in pregnancy: critical role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311: F1125–F1134, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00129.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu C, Lu A, Lu X, Zhang L, Fang H, Zhou L, Yang T. Activation of renal (pro)renin receptor contributes to high fructose-induced salt sensitivity. Hypertension 69: 339–348, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu C, Lu A, Wang H, Fang H, Zhou L, Sun P, Yang T. (Pro)Renin receptor regulates potassium homeostasis through a local mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F641–F656, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00043.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Z, Xu L, Li W, Jin X, Song X, Chen X, Zhu J, Zhou S, Li Y, Zhang W, Dong X, Yang X, Liu F, Bai H, Chen Q, Su C. Innate scavenger receptor-A regulates adaptive T helper cell responses to pathogen infection. Nat Commun 8: 16035, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou L, Liu G, Jia Z, Yang KT, Sun Y, Kakizoe Y, Liu M, Zhou S, Chen R, Yang B, Yang T. Increased susceptibility of db/db mice to rosiglitazone-induced plasma volume expansion: role of dysregulation of renal water transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1491–F1497, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00004.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]