Abstract

Progressive superior shift of the mitral valve (MV) during systole is associated with abnormal papillary muscle (PM) superior shift in late systolic MV prolapse (MVP). The causal relation of these superior shifts remains unclarified. We hypothesized that the MV superior shift is related to augmented MV superiorly pushing force by systolic left ventricular pressure due to MV annular dilatation, which can be corrected by surgical MV plasty, leading to postoperative disappearance of these superior shifts. In 35 controls, 28 patients with holosystolic MVP, and 28 patients with late systolic MVP, the MV coaptation depth from the MV annulus was measured at early and late systole by two-dimensional echocardiography. The PM tip superior shift was monitored by echocardiographic speckle tracking. MV superiorly pushing force was obtained as MV annular area × (systolic blood pressure − 10). Measurements were repeated after MV plasty in 14 patients with late systolic MVP. Compared with controls and patients with holosystolic MVP, MV and PM superior shifts and MV superiorly pushing force were greater in patients with late systolic MVP [1.3 (0.5) vs. 0.9 (0.6) vs. 3.9 (1.0) mm/m2, 1.3 (0.5) vs. 1.2 (1.0) vs. 3.3 (1.3) mm/m2, and 487 (90) vs. 606 (167) vs. 742 (177) mmHg·cm2·m−2, respectively, means (SD), P < 0.001]. MV superior shift was correlated with PM superior shift (P < 0.001), which was further related to augmented MV superiorly pushing force (P < 0.001). MV and PM superior shift disappeared after surgical MV plasty for late systolic MVP. These data suggest that MV annulus dilatation augmenting MV superiorly pushing force may promote secondary superior shift of the MV (equal to late systolic MVP) that causes subvalvular PM traction in patients with late systolic MVP.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Late systolic mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is associated with mitral valve (MV) and papillary muscle (PM) abnormal superior shifts during systole, but the causal relation remains unclarified. MV and PM superior shifts were correlated with augmented MV superiorly pushing force by annular dilatation and disappeared after surgical MV plasty with annulus size and MV superiorly pushing force reduction. This suggests that MV annulus dilatation may promote secondary superior shifts of the MV (late systolic MVP) that cause subvalvular PM traction.

Keywords: echocardiography, mitral valve, mitral valve prolapse

INTRODUCTION

The distance from the base of papillary muscles (PMs) to the mitral valve (MV) annulus as well as the distance from the base to the tip of PMs physiologically shorten in systole. Consequently, the distance between the PM tip and MV annulus (PM tip depth) is kept relatively constant throughout systole in normal individuals (Fig. 1, top) (17). These subvalvular geometric stabilities in normal individuals contribute to the approximately constant MV coaptation depth from the MV annulus throughout systole. Late systolic MV prolapse (MVP) is defined as a progressive superior shift of MV coaptation toward the left atrium (LA) during systole, causing midsystolic click and late systolic murmur, ventricular extrasystoles, T wave inversion, sudden death, heart failure, and other conditions (2, 11, 12, 32). Redundant chordae and/or inadequate PM contraction are considered causes of late systolic MVP (2). Angiographic studies have demonstrated a hyperdynamic inward “buckling” of the posterior left ventricular (LV) wall in patients with severe MVP and have related this buckling to traction of LV wall segments by superiorly drawn PMs (12). Sanfilippo et al. (28) used two-dimensional echocardiography and demonstrated an abnormal systolic superior shift of PM tips toward the LA in patients with classic MVP (Fig. 1, bottom). Therefore, an abnormal superior shift of MV coaptation in patients with late systolic MVP is associated with an abnormal superior shift of the subvalvular PM tip. However, questions remain regarding the mechanism or causal relation between these two superior shifts. Does the primary superior shift of PMs cause the secondary superior shift of MV coaptation or vice versa? Confirming this causal relation may lead to further insights into the fundamental mechanism of late systolic MVP. An additional remaining question is the dynamics of whole PMs, including PM base shift and PM contraction.

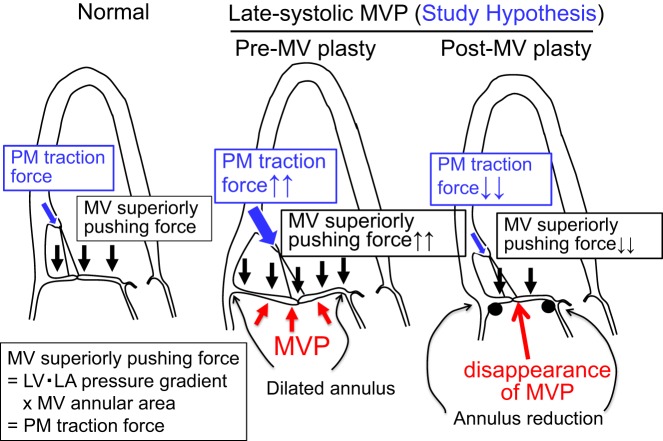

Fig. 1.

Subvalvular left ventricular (LV) base and papillary muscle (PM) dynamics in normal subjects (top) and patients with late systolic mitral valve prolapse (MVP, bottom). Top: from early to late systole, the mitral valve (MV) annulus-to-PM base distance (distance 1) shortens to distance 1′. The PM base-to-tip distance (distance 2) shortens to distance 2′. Consequently, the PM tip depth from the MV annulus (distance 3) remains approximately constant (distance 3 = distance 3′). These dynamics allow approximately constant MV coaptation depth throughout systole in normal subjects. Bottom: in contrast, PM tip depth (distance 3) significantly shortens in patients with late systolic MVP (distance 3 > distance 3′), accompanying a progressive superior shift of MV during systole (equal to late systolic MVP as indicated by red arrows). Details and causal relation of these subvalvular abnormalities have yet to be clarified.

Systolic LV pressure superiorly pushes the MV leaflet toward the LA (Fig. 2, left). This MV superiorly pushing force can be obtained as (LV systolic pressure − LA pressure) × MV annular area and expresses the PM traction force (1). Late systolic MVP is associated with prominent MV annular dilatation (3, 5, 16), which is expected to augment the MV superiorly pushing force. Regarding the causal relation between superior shifts of MV coaptation and PMs, one possibility is that augmented MV leaflet pushing force with annular dilatation may shift MV coaptation and leaflets superiorly, which may cause further traction and shift PMs superiorly (Fig. 2, middle). Therefore, we hypothesized that a superior shift of MV coaptation in patients with late systolic MVP is associated with a superior shift of the PM tip and augmented MV superiorly pushing force with annular dilatation. These associations will not indicate causal relations, which require further observations of the changes in these superior shifts with changes in the augmented MV superiorly pushing force, as changes in the MV superiorly pushing force will not influence the “primary” superior shift of PMs. Such opportunities are present after surgical MV plasty with annulus size reduction, which leads to a considerable reduction in the MV superiorly pushing force. We further hypothesized that superior shifts of MV coaptation as well as those of PMs in patients with late systolic MVP will be attenuated or will disappear after surgical MV plasty with annulus size reduction (Fig. 2, right), suggesting that the superior shift of MV coaptation causes that of subvalvular PMs. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the relation between the systolic superior shift of MV coaptation, augmented MV leaflet superiorly pushing force, and superior shift of the PM tip in preoperative and postoperative patients with late systolic MVP. An additional purpose was to evaluate the dynamics of PM base shift and PM contraction. Quantitative two-dimensional echocardiography with speckle-tracking analysis was used for the analysis (24). This investigation is important because it may clarify the causal relation between the superior shift of the MV and that of PMs in late systolic MVP. This investigation may further clarify the role of MV annular dilatation in the mechanism of late systolic MVP and influences of MV annular size reduction on MV leaflet and subvalvular PM abnormalities. The results of this study may help decision making regarding the MV surgical strategy.

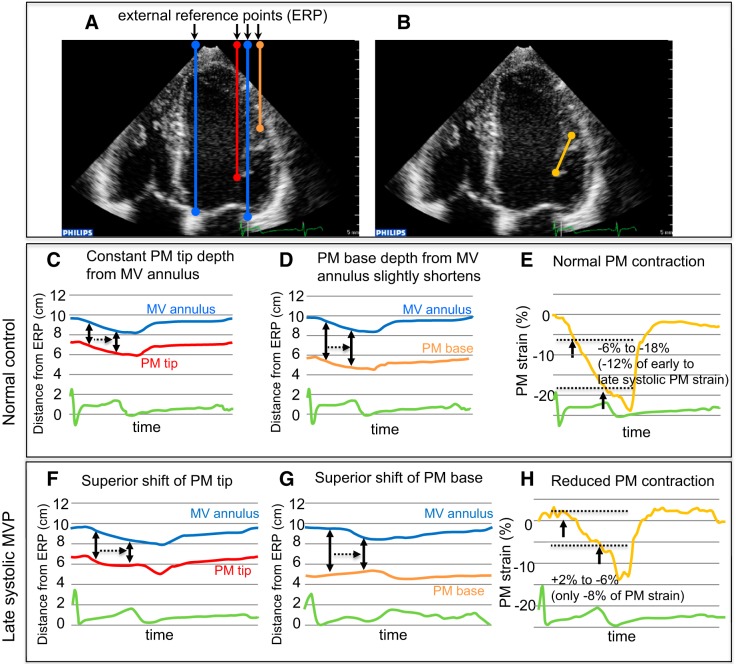

Fig. 2.

Potential mechanism of late systolic mitral valve prolapse (MVP) with augmented mitral valve (MV) superiorly pushing force and MV annulus dilatation. Left ventricular (LV)-to-left atrial (LA) systolic pressure gradient physiologically pushes MV leaflets superiorly (panel at left). This force can be calculated as LV-to-LA pressure gradient × MV annular area and expresses the papillary muscle (PM) traction force. In patients with late systolic MVP (panel in middle), the MV superiorly pushing force as well as PM traction force can be augmented with marked annular dilatation, which may potentially lead to abnormal superior shifts of MV leaflets that cause PM traction. After surgical MV plasty with annulus size reduction (panel at right), the MV superiorly pushing force as well as PM traction force can be considerably reduced, which may attenuate or eliminate the preoperatively observed abnormal superior shifts of both MV leaflets and PMs.

METHODS

Study participants.

Thirty-six consecutive patients with holosystolic MVP and 33 patients with late systolic MVP who underwent echocardiographic examination were prospectively enrolled in this study. Definitions of holosystolic and late systolic MVP will be described later. Forty age-matched controls consisted of normal volunteers and those who had undergone echocardiographic examination for clinical reasons but were finally judged to have no significant cardiac disease. Among these enrolled subjects, five controls, eight patients with holosystolic MVP, and five patients with late systolic MVP were excluded because of inadequate images for speckle-tracking analysis. The remaining 35 controls, 28 patients with holosystolic MVP, and 28 patients with late systolic MVP were included as study participants.

Regarding the surgery for holosystolic MVP, annuloplasty was performed in all 18 patients. A full semirigid ring was implanted in 15 patients, and a full flexible ring was implanted in 3 patients. Ring size ranged from 26 to 34 mm [30 (2) mm, mean (SD)]. Chordal reconstruction was performed on the medial side in five patients and on the lateral side in two patients. Posterior and anterior leaflet resection was performed in 11 and 1 patients, respectively. Regarding the surgery for late systolic MVP, annuloplasty was performed in all 14 patients. A full and partial ring was implanted in 10 and 4 patients, respectively. Semirigid and flexible ring was implanted in 2 and 12 patients, respectively. Ring size ranged from 27 to 36 mm [33 (3) mm]. Chordal reconstruction was performed on the medial side in five patients, on the lateral side in three patients, and on both sides in five patients. Posterior leaflet resection was performed in nine patients, but anterior leaflet resection was not performed.

Echocardiography was repeated 5–45 days [16 (13) days] and 3–11 days [7 (3) days] after surgical MV plasty in 18 patients with holosystolic MVP and 14 patients with late systolic MVP, respectively. To evaluate effects of surgery in the chronic phase, echocardiography was performed both early after [24 (20) days after] and late after [355 (31) days after] surgery in six patients with holosystolic MVP. Similarly, echocardiography was performed both early after [6 (1) days after] and late after [253 (90) days after] surgery in five patients with late systolic MVP.

This is an observational study without randomization or interventions. Echocardiography was performed with clinical indications, and no procedures were performed for purposes of research. The institutional review board approved this study (no. H30-020), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

General echocardiographic measurements.

Commercially available echocardiographic scanners were used (Philips iE33, Philips, Andover, MA). All scanners were managed according to previously published guidelines (7). In apical four- and two-chamber views, LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), LV end-systolic volume (LVESV), and LA end-systolic volume were measured by biplane Simpson’s method (33). MV annular area in midsystole was measured by the annular dimension in apical four- and two-chamber views with an elliptical assumption (22, 25). MV annular area × (systolic blood pressure − 10) was defined as the MV superiorly pushing force, assuming that LA pressure is 10 mmHg (1). This force is also referred to as the PM traction force by MV leaflets. Mitral regurgitation (MR) vena contracta width (narrowest jet width by color Doppler echocardiography) was measured in the parasternal or apical view with the best MR jet visualization (13). MR volume was calculated as the difference between the LV ejection volume (LVEDV − LVESV) and aortic stroke volume as determined by pulsed Doppler (35). Effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) was also obtained using the combination of the proximal isovelocity surface area method and continuous wave Doppler MR velocity profile. Forearm blood pressure was measured during the echocardiographic examination using a standard cuff technique.

Measurement of systolic superior shift of MV coaptation toward the LA.

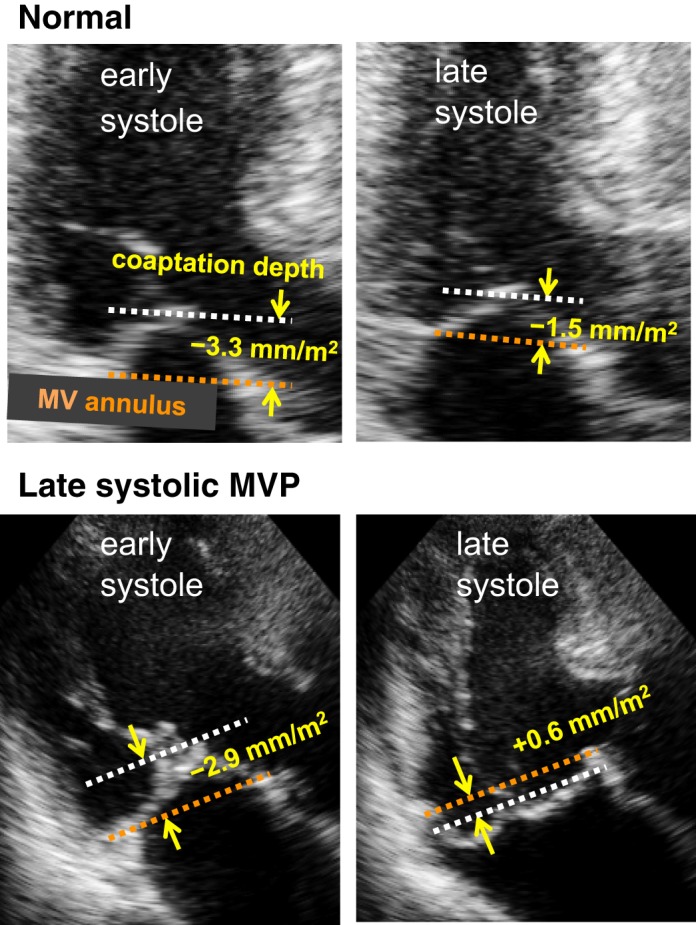

In apical views with the best visualization of the MV leaflet and its prolapse, MVP was defined as superior displacement during systole of the MV coaptation beyond the annular level (20). The distance from the MV annulus level to leaflet coaptation was measured and defined as “coaptation depth” (Fig. 3). This measurement was repeated in the early systolic (1/4 systole) frame with MV closure and the late systolic (3/4 systole) frame. Coaptation depth normalized by body surface area was only modestly increased [−3.4 (1.1) to −2.0 (1.3) mm/m2, P < 0.01] in normal participants (Table 1 and Fig. 3). An augmented shift of MV coaptation beyond the normal range (mean + 2 SDs = 2.3 mm/m2) was defined as late systolic MVP (Fig. 3, bottom). In the evaluation of postoperative change in MV leaflet superior shift, leaflet depth relative to MV annulus was measured at the middle point of the medial and lateral half of MV leaflet, respectively, in the apical two-chamber view. This allows evaluation of regional influence by chordal reconstruction on superior shifts of MV coaptation/leaflet on the side of chordal reconstruction as well as on the contralateral side.

Fig. 3.

Measurement of the systolic superior shift of mitral valve (MV) coaptation. Depths of MV coaptation in early and late systole were measured as its distance (yellow arrows) from the line connecting the MV annulus in apical echocardiographic views with the best visualization of the MV and/or mitral valve prolapse (MVP). Top: in this normal subject, MV coaptation depth slightly increases in systole (−3.3 to −1.5 mm/m2). Bottom: in contrast, MV coaptation depth considerably increases in this patient with late systolic MVP (−2.9 to +0.6 mm/m2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and basic echocardiographic measurements

| Control | Holosystolic MVP | Late Systolic MVP | P Value (ANOVA or χ2-Test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 35 | 28 | 28 | |

| Age, yr | 52 (19) | 58 (16) | 50 (16) | 0.22 |

| Sex (M/F), n | 21/14 | 20/8 | 17/11 | 0.24 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 65 (10) | 68 (13) | 61 (12) | 0.62 |

| Rhythm (sinus/AF), n | 35/0 | 27/1 | 28/0 | 0.38 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 124 (14) | 126 (16) | 122 (20) | 0.71 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 72 (10) | 75 (11) | 74 (15) | 0.63 |

| LVEDV, ml/m2 | 56 (10) | 74 (21)† | 82 (24)† | 0.01 |

| LVESV, ml/m2 | 20 (5) | 26 (9) | 31 (13)† | 0.02 |

| EF, % | 62 (5) | 65 (8) | 63 (7) | 0.08 |

| SV, ml/m2 | 35 (7) | 32 (5) | 34 (6) | 0.34 |

| LA volume, ml/m2 | 22 (8) | 64 (28)† | 56 (25)*† | <0.01 |

| MV annular area, cm2/m2 | 4.3 (0.7) | 5.3 (1.0)† | 6.7 (1.7)*† | <0.01 |

| VC width, mm/m2 | 0.4 (0.7) | 3.2 (1.1)† | 3.3 (1.0)† | <0.01 |

| EROA, cm2/m2 | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.26 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.17) | <0.01 |

| MR volume, ml/m2 | 2.4 (1.1) | 27 (17)† | 23 (14)† | <0.01 |

| MV superiorly pushing force, mmHg·cm2·m−2 | 487 (90) | 606 (167)† | 742 (177)*† | <0.01 |

| Systolic superior shift of MV coaptation toward the LA, mm/m2 | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 3.9 (1.0)*† | <0.01 |

| Systolic inferior shift of the MV annulus toward the apex, mm/m2 | 4.7 (0.9) | 5.2 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.3) | 0.08 |

Values are means (SD); n = no. of subjects. AF, atrial fibrillation; BP, blood pressure; EF, ejection fraction; EROA, effective regurgitant orifice area; F, female; LA, left atrium; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; M, male; MR, mitral regurgitation; MV, mitral valve; MVP, mitral valve prolapse; SV, stroke volume; VC, vena contracta.

P < 0.05 vs. holosystolic MVP;

P < 0.05 vs. control.

Dynamic evaluation of PM and MV annulus motion by speckle-tracking analysis.

In apical four- and two-chamber views with PM visualization, distances between 1) the PM tip and fixed external reference point (ERP) around the cardiac apex, 2) the PM base and ERP, 3) the MV annulus and ERP, and 4) the base and tip of the PM were dynamically monitored by two-dimensional echocardiographic speckle-tracking analysis using commercially available software (“free strain,” Philips; Fig. 4, A–E, and Supplemental Videos S1−S3; Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology Heart and Circulatory Physiology website). Measurements of medial and lateral PMs were averaged. Details are described in the figures.

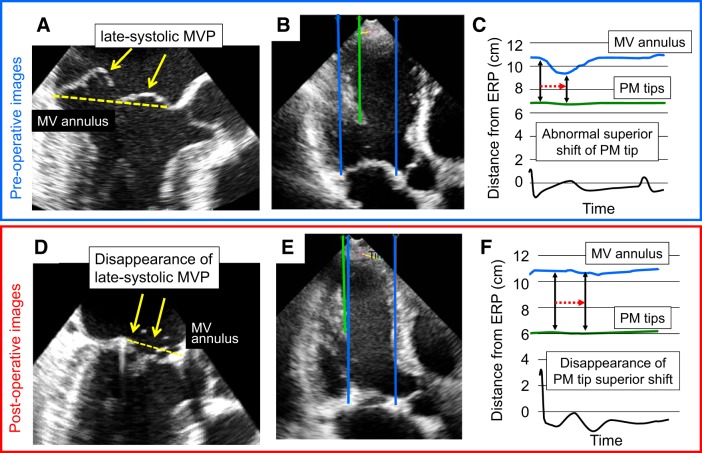

Fig. 4.

Dynamic evaluation of papillary muscles (PMs) and mitral valve (MV) annulus motion by any-two-point speckle-tracking analysis (“free strain”; Philips) in normal subjects and patients with late systolic mitral valve prolapse (MVP). A and B: in apical four- and two-chamber views with PM visualization, distances between 1) the PM tip and a fixed external reference point (ERP) around the apex (red), 2) the PM base and the ERP (orange), 3) the MV annulus and the ERP (blue), and 4) the PM base and tip (yellow) were dynamically tracked and monitored (Supplemental Videos S1–S3). These analyses allow monitoring of the PM tip depth from the MV annulus and other subvalvular dynamics. C: the upper blue and lower red lines indicate the distances from the ERP to the MV annulus or PM tip, respectively. The distance between the blue and red lines indicates the PM tip depth from the MV annulus. This PM tip depth is approximately constant during the whole systole in this normal subject. D: the upper blue and lower orange lines indicate distances from the ERP to the MV annulus or PM base, respectively. The distance between the blue and orange lines indicates the PM base depth from the MV annulus. This PM base depth slightly shortens during systole in this normal subject. E: the yellow line indicates the rate of temporal change in the distance (strain) between the PM base and tip (PM length) from the onset of systole. The PM length shortens during systole in this normal subject, and the PM strain changes from −6% in early systole to −18% in late systole (early to late systolic PM strain = −12%). F: compared with that in C of a normal subject, the PM tip depth from the MV annulus is considerably reduced in systole, demonstrating an abnormal systolic superior shift of the PM tip in this patient with late systolic MVP. G: compared with that in D, the distance between the ERP and PM base paradoxically lengthens, and the PM base depth is clearly reduced in systole, indicating an abnormal systolic superior shift of the PM base in this patient with late systolic MVP. H: compared with that in E, systolic PM strain is +2% in early systole and −6% in late systole (early to late systolic PM strain = −8%), demonstrating reduced PM contraction in this patient with late systolic MVP.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed according to a standard guideline (21). Distances, such as coaptation depth, or volumes, such as LV volume, were normalized by body surface area for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were compared among the three groups using ANOVA. When statistical significance was detected by ANOVA, the Wilcoxon test was used to test the difference in continuous variables between two groups. Incidence rates were compared among two or three groups using the χ2-test. Univariate Spearman correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between the systolic superior shift of MV coaptation and other echocardiographic measurements, including superior shifts of the PM base and tip toward the LA, PM shortening and strain, LVEDV, and LVESV. The systolic shift of the base or tip of the PM, PM shortening, and PM strain were also correlated with the MV annular area or MV superiorly pushing force. Multivariate analysis was further performed for variables with significant correlations as determined by univariate analysis.

Intraobserver variability for speckle-tracking measurements was performed by the analysis of measurements in 10 randomly selected patients by the same observer at two different time points. Interobserver variability was performed by the analysis of measurements in the other 10 patients by 2 independent blinded observers. The results were analyzed by both least-squares fit linear regression analysis and the Bland-Altman method.

RESULTS

Profile of the patients.

The profiles of patients are shown in Table 1. By definition, early to late systolic superior shift of MV coaptation toward the LA was significantly more pronounced in patients with late systolic MVP than in controls and patients with holosystolic MVP (P < 0.01). Systolic inferior shifts of the MV annulus toward the apex were not significantly different among the three groups. These results indicate that the augmented systolic superior shift of MV coaptation relative to the MV annulus in patients with late systolic MVP reflects an abnormal superior shift of MV coaptation rather than an increased inferior shift of the MV annulus. LVEDV, LVESV, ejection fraction, MR volume, and vena contracta width were not significantly different between patients with holosystolic MVP and those with late systolic MVP. LA volume was smaller in patients with late systolic MVP. In addition, the MV annular area was significantly larger in patients with late systolic MVP than in those with holosystolic MVP, as previously reported (32), resulting in significantly greater MV superiorly pushing force in patients with late systolic MVP than in those with holosystolic MVP. These measures were not significantly different between patients with relatively lower heart rate and those with higher heart rate both in holosystolic MVP as well as in late systolic MVP (Supplemental Table S1).

Impaired stability in subvalvular geometry in late systolic MVP.

The systolic superior shift of the PM tip toward the LA was significantly greater in patients with late systolic MVP than in patients with holosystolic MVP and controls (P < 0.01; Table 2 and Fig. 4F as well as Supplemental Video S4). The systolic superior shift of the PM base was also significantly greater in patients with late systolic MVP than in the other two groups (P < 0.01; Fig. 4G as well as Supplemental Video S5). PM shortening and its ratio (strain) were significantly reduced in patients with late systolic MVP compared with patients with holosystolic MVP and controls (P < 0.01; Fig. 4H as well as Supplemental Video S6). Notably, PM shortening or strain in this study was measured by comparison of late systolic versus early systolic values, as opposed to comparison of end-systolic versus end-diastolic values. Therefore, lower PM shortening or strain values were obtained in this study than in previous reports (4, 34). These measures were also not significantly different between patients with relatively lower heart rate and those with higher heart rate both in holosystolic MVP as well as in late systolic MVP (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 2.

Early to late systolic dynamics of subvalvular PMs

| Control | Holosystolic MVP | Late Systolic MVP | P Value (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 35 | 28 | 28 | |

| Systolic superior shift of the PM tip toward the LA, mm/m2 | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.2 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.3)*† | <0.01 |

| Systolic superior shift of the PM base toward the LA, mm/m2 | 2.5 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.9)† | 3.6 (1.4)*† | <0.01 |

| PM shortening, mm/m2 | −1.5 (0.5) | −1.7 (0.6) | −0.9 (0.6)*† | <0.01 |

| PM strain, % | −11 (3) | −13 (4) | −8 (3)*† | <0.01 |

Values are means (SD); n = no. of subjects. LA, left atrium; MVP, mitral valve prolapse; PM, papillary muscle.

P < 0.05 vs. holosystolic MVP;

P < 0.05 vs. control.

Systolic shift of MV coaptation and impaired stability in subvalvular geometry.

By univariate analysis, the systolic superior shift of MV coaptation toward the LA was significantly correlated with the systolic shift of the PM tip toward the LA (r = 0.684, P < 0.01), reduced PM strain (r = 0.630, P < 0.01), and the MV superiorly pushing force (r = 0.542, P < 0.01). By multivariate analysis, the systolic superior shift of MV coaptation was primarily correlated with the systolic superior shift of PM tips (Fig. 5A) along with reduced PM strain and augmented MV superiorly pushing force (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

A: significant relationship between the systolic superior shift of the papillary muscle (PM) tip and superior shift of mitral valve (MV) coaptation. An augmented superior shift of MV coaptation was associated with an increased superior shift of the PM tip. B: significant relation between the MV superiorly pushing force and the superior shift of the PM tip. The augmented superior shift of the PM tip was associated with an increased MV superiorly pushing force due to MV annular dilatation.

Table 3.

Factors associated with superior shifts of MV coaptation and the PM tip

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P Value | Standardized β | P Value | |

| Superior shift of MV coaptation | ||||

| LVEDV | 0.123 | 0.37 | ||

| LVESV | 0.100 | 0.46 | ||

| LA volume | −0.041 | 0.82 | ||

| VC width | 0.093 | 0.50 | ||

| MV superiorly pushing force | 0.542 | <0.01 | 0.238 | <0.01 |

| Inferior shift of the MV annulus | 0.125 | 0.36 | ||

| Superior shift of the PM tip | 0.684 | <0.01 | 0.475 | <0.01 |

| PM strain | 0.630 | <0.01 | 0.400 | <0.01 |

| Superior shift of the PM tip | ||||

| LVEDV | 0.111 | 0.42 | ||

| LVESV | −0.019 | 0.89 | ||

| LA volume | −0.165 | 0.37 | ||

| VC width | −0.010 | 0.94 | ||

| MV superiorly pushing force | 0.460 | <0.01 | 0.387 | <0.01 |

| PM strain | 0.376 | 0.01 | 0.272 | 0.03 |

LA, left atrium; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MV, mitral valve; PM, papillary muscle; VC, vena contracta.

By univariate analysis, the systolic superior shift of the PM tip was significantly correlated with the MV superiorly pushing force (r = 0.460, P < 0.01) and PM strain (r = 0. 376, P = 0.01). By multivariate analysis, the systolic superior shift of the PM tip was primarily correlated with augmented MV superiorly pushing force (Fig. 5B).

Changes in echocardiographic parameters after surgical MV plasty.

In 18 patients with holosystolic MVP, LVEDV was significantly reduced, whereas LVESV tended to be reduced, after surgical MV plasty, resulting in a reduced ejection fraction. The LA volume was reduced, and the MV annular area was reduced, resulting in reduced MV superiorly pushing force after surgery. Neither systolic superior shifts of MV coaptation or PM tip nor PM strain were different compared with controls in the preoperative stage, nor did they change after the surgery (Table 4). In seven patients with a single chordal reconstruction at either medial or lateral PM, postoperative changes in neither systolic superior shift of MV leaflet, systolic superior shift of PM tip, nor PM strain were significantly different between the chordal reconstruction side and contralateral side.

Table 4.

Changes in echocardiographic parameters following surgical MV plasty in patients with holosystolic and late systolic MVP

| Holosystolic MVP |

Late Systolic MVP |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | Postop | P Value | Preop | Postop | P Value | |

| LVEDV, ml/m2 | 87 (12) | 67 (11) | <0.01 | 95 (37) | 67 (24) | 0.01 |

| LVESV, ml/m2 | 32 (9) | 30 (8) | 0.58 | 37 (16) | 30 (19) | 0.42 |

| EF, % | 62 (10) | 55 (7) | 0.02 | 62 (8) | 50 (11) | 0.05 |

| LA volume, ml/m2 | 67 (28) | 43 (11) | <0.01 | 69 (28) | 36 (13) | <0.01 |

| MV annular area, cm2/m2 | 5.5 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.7) | <0.01 | 7.7 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| VC width, mm/m2 | 4.1 (1.0) | 0.7 (0.4) | <0.01 | 3.7 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| MV superiorly pushing force, mmHg·cm2·m−2 | 655 (143) | 425 (109) | <0.01 | 922 (198) | 407 (96) | <0.01 |

| Systolic superior shift of MV coaptation, mm/m2 | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.39 | 4.2 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Chordal reconstruction side | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.87 | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Contralateral side | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.69 | 3.1 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Systolic superior shift of the PM tip, mm/m2 | 1.5 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.9) | 0.31 | 3.8 (1.5) | 0.7 (0.9) | <0.01 |

| Chordal reconstruction side | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.22 | 4.0 (2.3) | 0.7 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| Contralateral side | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.80 | 3.6 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| PM strain | −13 (4) | −13 (7) | 0.93 | −8 (3) | −13 (4) | 0.01 |

| Chordal reconstruction side | −13 (6) | −14 (5) | 0.89 | −8 (4) | −13 (2) | 0.01 |

| Contralateral side | −13 (5) | −12 (7) | 0.96 | −9 (4) | −13 (4) | <0.01 |

Values are means (SD); n = 18 patients with holosystolic mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and 14 patients with late systolic MVP. EF, ejection fraction; LA, left atrium; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MV, mitral valve; PM, papillary muscle; Postop, postoperative; Preop, preoperative; VC, vena contracta.

In 14 patients with late systolic MVP, LVEDV was significantly reduced, whereas LVESV tended to be reduced, after surgical MV plasty, resulting in a reduced ejection fraction. LA volume was reduced, and these changes were similar to those of patients with holosystolic MVP. In contrast, the MV annular area was highly reduced, which led to dramatically reduced MV superiorly pushing force after the surgery. Notably, the abnormal superior shifts of both MV coaptation and PM tip in the preoperative stage disappeared or were reduced to a normal range after surgery (Fig. 6 as well as Supplemental Videos S7 and S8). In addition, PM strain, which was low preoperatively, was significantly increased after surgical MV plasty (Table 4). These postoperative changes in impaired stability of MV and PMs were not different between patients with larger (>30 mm) and smaller (≤30 mm) ring implantations [change in superior shift of MV coaptation/leaflet: −3.1 (1.4) vs. −2.4 (1.1) mm/m2; change in superior shift of PM tip: −3.4 (1.5) vs. −2.7 (0.7) mm/m2; change in PM strain: −4.5 (6.7) vs. −3.6 (0.7)%, respectively, all not significant]. In eight patients with a single chordal reconstruction at either medial or lateral PM, systolic superior shift of MV leaflet on the chordal reconstruction side and that on the contralateral side showed similar postoperative reduction or disappearance (not significant; Table 4). In addition, postoperative reduction in superior shift of PM tip as well as improvement in PM strain were also similar between the chordal reconstruction side and contralateral side (not significant).

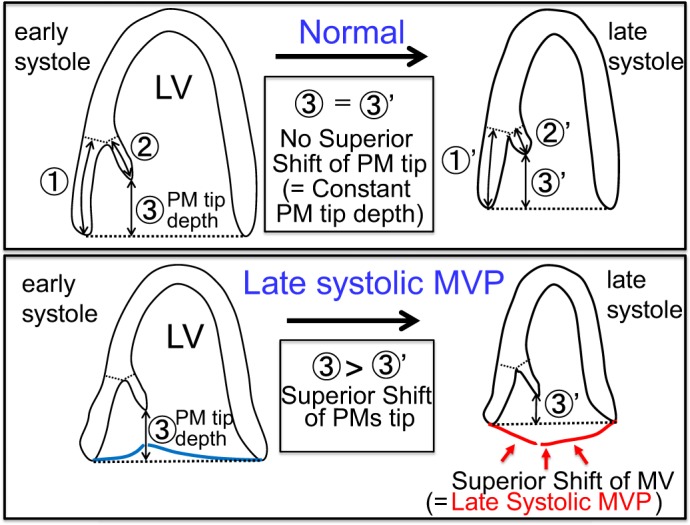

Fig. 6.

Disappearance of abnormal systolic superior shifts of both mitral valve (MV) coaptation and the papillary muscle (PM) tip in a patient with late systolic MV prolapse (MVP) following surgical MV plasty. A–C: before surgical MV plasty. D–F: after surgical MV plasty. The systolic superior shift of MV coaptation (MVP) was clearly observed before surgical MV plasty (A). However, this observation disappeared after the surgery (D). The systolic superior shift of the PM tip was also clearly observed before the surgery (C). However, this observation disappeared after the surgery (F). ERP, external reference point.

In six and five patients with holosystolic or late systolic MVP, postoperative echocardiography was repeated in both the acute and chronic phases after surgery. LV and LA volume tended to be reduced and LV ejection fraction tended to increase in the chronic phase but without statistical difference. Indexes of subvalvular geometry were also generally similar between these two phases (Supplemental Table S2).

Reproducibility of measurement of superior shift of PM tip and PM strain.

Good correlations were observed in intraobserver and interobserver variability of these echocardiographic measurements. Values were r = 0.95 and 0.92 for superior shift of PM tip and r = 0.96 and 0.93 for PM strain. From the Bland-Altman method, intraobserver and interobserver analysis indicated a mean difference of −0.22 mm/m2 (95% confidence interval: −1.28 to 0.84 mm/m2) and 0.12 mm/m2 (95% confidence interval: −1.23 to 1.47 mm/m2) for superior shift of the PM tip and −0.11% (95% confidence interval: −3.1 to 2.9%) and −0.27% (95% confidence interval: −4.0 to 3.4%) for PM strain.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that patients with late systolic MVP have impaired subvalvular geometric stability, including a systolic superior shift of PMs toward the LA and reduced PM shortening (contraction), compared with normal individuals and those with holosystolic MVP. The systolic superior shift of MV coaptation toward the LA, constituting the central pathophysiology of late systolic MVP, was significantly correlated with these subvalvular abnormalities. Although it is known that patients with holosystolic and late systolic MVP frequently exhibit subvalvular lesions, the results suggest that late systolic MVP is associated with the abovementioned specific subvalvular geometric instabilities. This association of the systolic superior shift of both MV coaptation/leaflets and subvalvular PMs can be interpreted as follows. Possibility 1 is that a superior shift of MV leaflet tract PMs results in a superior shift of PMs. Possibility 2 is that the primary superior shift of PMs leads to a resultant superior shift of MV coaptation/leaflets. The association of these superior shifts alone may not suggest a causal relation. Notably, the superior shift of MV coaptation as well as that of subvalvular PMs disappears after surgical MV plasty, including MV annulus size reduction with ring implantation, leaflet resection/suture, and prosthetic chordae implantation. These procedures may not influence the “primary superior shift of PMs” but do reduce superiorly pushing force on the MV. Therefore, the postoperative disappearance of systolic superior shifts of both MV coaptation/leaflets and PMs suggests the possibility that systolic superior shifts of MV leaflets cause subvalvular PM traction and induce its superior shift.

Patients with late systolic MVP in our study had a highly dilated MV annulus and increased MV superiorly pushing force. Prominent MV annular dilatation in late systolic MVP is consistently reported in other studies and suggests that the dilatation is primary in nature as opposed to secondary to MR (32). MV annular dilatation and MV superiorly pushing force were significantly correlated with subvalvular abnormalities, including superior shifts of the PM tip and base as well as reduced PM contraction. In addition, these subvalvular instabilities disappeared after MV plasty with reductions in MV annulus size and MV superiorly pushing force. These findings strongly suggest that MV annulus dilatation with augmented MV superiorly pushing force may lead to secondary superior shifts of MV leaflets that cause superior traction of PMs in patients with late systolic MVP.

PM contraction (strain) was significantly reduced in patients with late systolic MVP. This reduction improved after surgical MV plasty with annular size reduction, leading to reduced MV superiorly pushing force (equal to PM traction force). It may be possible that preoperative reduced PM contraction as well as abnormal superior shift of PMs in patients with late systolic MVP could be attributed to the reversible afterload mismatch of PMs, in a broad sense, due to an enlarged MV annulus. Patients with ischemic heart disease occasionally show MVP with PM dysfunction (4); however, in this case, PM dysfunction may not be reversible. The presence or absence of advanced MV annulus dilatation may suggest the reversibility of reduced PM contraction.

In 7 patients with holosystolic MVP and 12 patients with late systolic MVP, chordal reconstruction was performed. This may influence postoperative changes in superior displacement of MV leaflet and subvalvular PM dynamics. However, neither postoperative changes nor the lack of changes in these were different between the chordal reconstruction side and the contralateral side either in patients with holosystolic MVP or in those with late systolic MVP. These data suggest that postoperative improvement in superior shift of MV coaptation/leaflet as well as subvalvular instabilities in patients with late systolic MVP seems to be independent of regional chordal reconstruction.

LV ejection fraction was reduced after surgical MV plasty in both groups with holosystolic or late systolic MVP (P < 0.01). This finding is consistent with previous studies, including data from both early and late after surgery (26, 30). We do not consider that the postoperative reduction in LV ejection fraction expresses LV dysfunction caused by surgery. Preoperative ejection fraction can be overestimated because of the presence of MR, and this disappears after surgery. In fact, LV maximal elasticity increases but ejection fraction is reduced after MV surgery for MR (29). Therefore, the postoperative reduction in ejection fraction in this study does not necessarily mean postoperative LV dysfunction.

Relation to previous studies.

Angiographic studies have demonstrated an abnormal “buckling” motion of the LV posterior wall with a systolic superior shift of PMs toward the LA (12). This observation was confirmed by the present study as a significantly increased superior shift of the PM base toward the LA by speckle tracking. Sanfilippo et al. (28) demonstrated a critical role for the systolic superior shift of PM tips toward the LA in the genesis of classical MVP. This observation was also confirmed by the present study as a systolic superior shift of the PM tip and its close relation to the systolic superior shift of MV coaptation. This study, with speckle-tracking analysis and dynamic monitoring of PMs and MV annulus, further demonstrated impaired stability in whole subvalvular geometry, including abnormal PM tip and base superior shifts and reduced PM shortening (contraction). In addition, this study demonstrated the disappearance of abnormal systolic superior shifts of MV coaptation/leaflets and PMs after surgical MV plasty with annulus size reduction. This finding provides important insights into the causal relation between systolic superior shifts of MV coaptation/leaflets and those of PMs. Lawrie (18) reported the postoperative disappearance of systolic superior shifts of both MV coaptation/leaflets and PMs after simple ring annuloplasty in patients with bileaflet late systolic MVP. This important observation strongly demonstrated the need to quantitatively evaluate MV coaptation and subvalvular PM dynamics. Our study confirmed their important study findings, further quantitated dynamic abnormalities of the MV and PM and suggested that MV annular dilatation to augment the superiorly pushing force on MV leaflets may induce a superior shift of MV leaflets to cause PM traction, causing secondary late systolic MVP. Important MV annulus-LV interactions have been reported. MV annular dilation is known to cause regional LV base dilatation, leading to localized, reduced contraction of the LV base by increased wall tension with Laplace’s law (9). The present study demonstrated a novel MV annulus-LV interaction. MV annular dilatation plays a central role in causing subvalvular PM instabilities and secondary late systolic MVP.

Clinical implications.

Impaired stability in subvalvular geometry may require consideration at the time of surgical MV plasty. It is not clear whether subvalvular abnormalities can be reproduced by a water test during surgery. Reproduction of late systolic MVP by a water test may depend on the LV pressure achieved during the test. Consideration of both possibilities (a successful or not successful reproduction of subvalvular abnormalities during a water test) seems to be important. Subvalvular abnormalities in patients with late systolic MVP appear to be secondary to the superiorly directed force on the MV. These abnormalities can be attenuated or eliminated by surgical annular size reduction (18). The postoperative disappearance of superior shifts of both MV coaptation/leaflets and PMs can be considered in advance during preoperative planning of MV surgery (27). Even when MR is eliminated by surgical MV leaflet repair, ring implantation may help stabilize MV leaflet and PM dynamics (19).

Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in patients with MVP have been reported (2, 6). Mechanical traction of PMs caused ventricular premature contraction in an animal model (10). The present study suggested the presence of PM traction in patients with late systolic MVP. This study may promote further studies to investigate the relationships between subvalvular abnormalities and arrhythmia. Most importantly, MV repair with annuloplasty may influence ventricular arrhythmia. Several seminal studies have suggested the beneficial influence of MV repair on ventricular arrhythmia (34a), requiring large-scale and randomized trials. Improved outcomes of early surgery for MVP may be related to the potential effects of MV surgery on arrhythmia, especially in patients with late systolic MVP (23). This hypothesis requires further studies.

Echocardiographic speckle-tracking analysis has been widely applied in research as well as in clinical practice. Applications are mainly for myocardial mechanics such as myocardial contraction, relaxation, passive stretch, and others (8, 14). This study has demonstrated a novel application of the tracking technique to evaluate MV annulus and subvalvular PM tip and base dynamics. This application may allow further investigation to study MV and subvalvular PM interactions, such as the role of PM dysfunction in MV function and others (34).

Limitations.

The number of studied patients is small; therefore, the values of subvalvular abnormalities in this study may not represent those of general patients with MVP. Because of the very small number of patients with atrial fibrillation (n = 1 in holosystolic MVP), influences of atrial fibrillation on the impaired stability of the valve and subvalvular region were not evaluated. Correlations between ventricular arrhythmias and subvalvular abnormalities and the effects of MV surgery on ventricular arrhythmia are critically important. However, electrophysiological investigations were not performed. For geometric studies, three-dimensional analysis is ideal (17a) but was not performed. In the present study, the systolic superior shift of the PM base toward the LA was mildly but significantly attenuated in patients with holosystolic MVP compared with controls. We speculate that frequent chordal rupture in these patients may reduce the longitudinal contraction of the LV base between the PMs and MV annulus attachment. However, this hypothesis was not proven.

Conclusions.

Late systolic MVP with systolic superior shift of MV coaptation/leaflets was associated with impaired stability in subvalvular geometry, including an abnormal systolic superior shift of the PM base and tip and reduced PM shortening/contraction. These systolic superior shifts of MV coaptation/leaflets and PMs dynamics were correlated with an augmented MV superiorly pushing force by annular dilatation. In addition, these superior shifts and abnormal subvalvular PM dynamics disappeared following surgical MV plasty with annulus size reduction, suggesting that MV leaflet/annulus enlargement to augment the superiorly pushing force on the MV may promote the secondary superior shift of MV coaptation (late systolic MVP) to cause subvalvular PM traction.

GRANTS

Y. Otsuji was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 17K09538.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.A.L. and Y.O. conceived and designed research; S.H., M.I., J.-Y.J., H.K., K.M., Y.-J.K., T.O., S.N., N.W., Y. Nabeshima and Y. Nishimura performed patient recruitment and image acquisition; S.H., S.F., and Y. Nagata analyzed data; S.H., S.F., and Y. Nagata interpreted results of patient recruitment and image acquisition; S.H. prepared figures; S.H. drafted manuscript; M.T., J.-K.S., and Y.O. edited and revised manuscript; Y.O. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplemental Data

REFERENCES

- 1.Askov JB, Honge JL, Jensen MO, Nygaard H, Hasenkam JM, Nielsen SL. Significance of force transfer in mitral valve-left ventricular interaction: in vivo assessment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 145: 1635–1641, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow JB, Bosman CK, Pocock WA, Marchand P. Late systolic murmurs and non-ejection (“mid-late”) systolic clicks. An analysis of 90 patients. Br Heart J 30: 203–218, 1968. doi: 10.1136/hrt.30.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulkley BH, Roberts WC. Dilatation of the mitral anulus. A rare cause of mitral regurgitation. Am J Med 59: 457–463, 1975. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burch GE, De Pasquale NP, Phillips JH. Clinical manifestations of papillary muscle dysfunction. Arch Intern Med 112: 112–117, 1963. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1963.03860010138015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra S, Salgo IS, Sugeng L, Weinert L, Tsang W, Takeuchi M, Spencer KT, O’Connor A, Cardinale M, Settlemier S, Mor-Avi V, Lang RM. Characterization of degenerative mitral valve disease using morphologic analysis of real-time three-dimensional echocardiographic images: objective insight into complexity and planning of mitral valve repair. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 4: 24–32, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.924332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesler E, King RA, Edwards JE. The myxomatous mitral valve and sudden death. Circulation 67: 632–639, 1983. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.67.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daimon M, Akaishi M, Asanuma T, Hashimoto S, Izumi C, Iwanaga S, Kawai H, Toide H, Hayashida A, Yamada H, Murata M, Hirano Y, Suzuki K, Nakatani S; Committee for Guideline Writing, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography . Guideline from Japanese Society of Echocardiography: 2018 focused update incorporated into guidance for the management and maintenance of echocardiography equipment. J Echocardiogr 16: 1–5, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12574-018-0370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Sherbeny WS, Sabry NM, Sharbay RM. Prediction of trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. J Echocardiogr, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12574-018-0394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda S, Song JK, Mahara K, Kuwaki H, Jang JY, Takeuchi M, Sun BJ, Kim YJ, Miyamoto T, Oginosawa Y, Sonoda S, Eto M, Nishimura Y, Takanashi S, Levine RA, Otsuji Y. Basal left ventricular dilatation and reduced contraction in patients with mitral valve prolapse can be secondary to annular dilatation: preoperative and postoperative speckle-tracking echocardiographic study on left ventricle and mitral valve annulus interaction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 9: e005113, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.005113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gornick CC, Tobler HG, Pritzker MC, Tuna IC, Almquist A, Benditt DG. Electrophysiologic effects of papillary muscle traction in the intact heart. Circulation 73: 1013–1021, 1986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.73.5.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigioni F, Enriquez-Sarano M, Ling LH, Bailey KR, Seward JB, Tajik AJ, Frye RL. Sudden death in mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet. J Am Coll Cardiol 34: 2078–2085, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00474-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman H, Fleming RJ, Engle MA, Levin AH, Ehlers KH. Angiocardiography in the apical systolic click syndrome. Left ventricular abnormality, mitral insufficiency, late systolic murmur, and inversion of T waves. Radiology 91: 898–904, 1968. doi: 10.1148/91.5.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall SA, Brickner ME, Willett DL, Irani WN, Afridi I, Grayburn PA. Assessment of mitral regurgitation severity by Doppler color flow mapping of the vena contracta. Circulation 95: 636–642, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.95.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatazawa K, Tanaka H, Nonaka A, Takada H, Soga F, Hatani Y, Matsuzoe H, Shimoura H, Ooka J, Sano H, Mochizuki Y, Matsumoto K, Hirata KI. Baseline global longitudinal strain as a predictor of left ventricular dysfunction and hospitalization for heart failure of patients with malignant lymphoma after anthracycline therapy. Circ J 82: 2566–2574, 2018. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-18-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagiyama N, Toki M, Hayashida A, Ohara M, Hirohata A, Yamamoto K, Totsugawa T, Sakaguchi T, Yoshida K, Isobe M. Prolapse volume to prolapse height ratio for differentiating Barlow’s disease from fibroelastic deficiency. Circ J 81: 1730–1735, 2017. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komeda M, Glasson JR, Bolger AF, Daughters GT II, Niczyporuk MA, Ingels NB Jr, Miller DC. Three-dimensional dynamic geometry of the normal canine mitral annulus and papillary muscles. Circulation 94, Suppl: II159–II163, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Kovalova S, Necas J, Mikula O. Discrimination between fibroelastic deficiency and Barlow disease using parameters of mitral annulus derived from real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. J Echocardiogr 11: 83–88, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s12574-013-0165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrie GM. Barlow disease: simple and complex. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 150: 1078–1081, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrie GM, Earle EA, Earle NR. Nonresectional repair of the Barlow mitral valve: importance of dynamic annular evaluation. Ann Thorac Surg 88: 1191–1196, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AP, Hsiung MC, Salgo IS, Fang F, Xie JM, Zhang YC, Lin QS, Looi JL, Wan S, Wong RH, Underwood MJ, Sun JP, Yin WH, Wei J, Tsai SK, Yu CM. Quantitative analysis of mitral valve morphology in mitral valve prolapse with real-time 3-dimensional echocardiography: importance of annular saddle shape in the pathogenesis of mitral regurgitation. Circulation 127: 832–841, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.118083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsey ML, Gray GA, Wood SK, Curran-Everett D. Statistical considerations in reporting cardiovascular research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H303–H313, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00309.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsey ML, Kassiri Z, Virag JAI, de Castro Brás LE, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Guidelines for measuring cardiac physiology in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314: H733–H752, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00339.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling LH, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, Orszulak TA, Schaff HV, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ, Frye RL. Early surgery in patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets: a long-term outcome study. Circulation 96: 1819–1825, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.6.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negishi T, Negishi K. Echocardiographic evaluation of cardiac function after cancer chemotherapy. J Echocardiogr 16: 20–27, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12574-017-0344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ormiston JA, Shah PM, Tei C, Wong M. Size and motion of the mitral valve annulus in man. I. A two-dimensional echocardiographic method and findings in normal subjects. Circulation 64: 113–120, 1981. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.64.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qulntana E, Suri RM, Thalji NM, Daly RC, Dearani JA, Burkhart HM, Li Z. Enriquez-Sarano M, Schaff HV. Left ventricular dysfunction after mitral valve repair–the fallacy of “normal” preoperative myocardial function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 148: 2752–2760, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaguchi T, Totsugawa T, Kuinose M, Tamura K, Hiraoka A, Chikazawa G, Yoshitaka H. Minimally invasive mitral valve repair through right minithoracotomy: 11-year single institute experience. Circ J 82: 1705–1711, 2018. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanfilippo AJ, Harrigan P, Popovic AD, Weyman AE, Levine RA. Papillary muscle traction in mitral valve prolapse: quantitation by two-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 19: 564–571, 1992. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(10)80274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Starling MR. Effects of valve surgery on left ventricular contractile function in patients with long-term mitral regurgitation. Circulation 92: 811–818, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suri RM, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Sundt TM, Daly RC, Mullany CJ, Enriquez-Sarano M, Orszulak TA. Recovery of left ventricular function after surgical correction of mitral regurgitation caused by leaflet prolapse. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 137: 1071–1076, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topilsky Y, Michelena H, Bichara V, Maalouf J, Mahoney DW, Enriquez-Sarano M. Mitral valve prolapse with mid-late systolic mitral regurgitation: pitfalls of evaluation and clinical outcome compared with holosystolic regurgitation. Circulation 125: 1643–1651, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres WM, Jacobs J, Doviak H, Barlow SC, Zile MR, Shazly T, Spinale FG. Regional and temporal changes in left ventricular strain and stiffness in a porcine model of myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H958–H967, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00279.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uemura T, Otsuji Y, Nakashiki K, Yoshifuku S, Maki Y, Yu B, Mizukami N, Kuwahara E, Hamasaki S, Biro S, Kisanuki A, Minagoe S, Levine RA, Tei C. Papillary muscle dysfunction attenuates ischemic mitral regurgitation in patients with localized basal inferior left ventricular remodeling: insights from tissue Doppler strain imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 113–119, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Yuan HT, Yang M, Zhong L, Lee YH, Vaidya VR, Asirvatham SJ, Ackerman MJ, Pislaru SV, Suri RM, Slusser JP, Hodge DO, Wang YT, Cha YM. Ventricular premature contraction associated with mitral valve prolapse. Int J Cardiol 221: 1144–1149, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ; American Society of Echocardiography . Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 16: 777–802, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.