Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE) is a devastating adverse outcome of pregnancy. Characterized by maternal hypertension, PE, when left untreated, can result in death of both mother and baby. The cause of PE remains unknown, and there is no way to predict which women will develop PE during pregnancy. The only known treatment is delivery of both the fetus and placenta; therefore, an abnormal placenta is thought to play a causal role. Women with obesity before pregnancy have an increased chance of developing PE. Increased adiposity results in a heightened state of systemic inflammation that can influence placental development. Adipose tissue is a rich source of proinflammatory cytokines and complement proteins, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of PE by promoting the expression of antiangiogenic factors in the mother. Because an aggravated inflammatory response, angiogenic imbalance, and abnormal placentation are observed in PE, we hypothesize that maternal obesity and complement proteins derived from adipose tissue play an important role in the development of PE.

Keywords: complement, immune, obesity, preeclampsia, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) is a devastating disorder of pregnancy and leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, affecting 2–8% of pregnancies worldwide (15). It is characterized by late gestational hypertension (systolic ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic ≥ 90 mmHg) combined with another sign/symptom such as proteinuria, renal insufficiency, or thrombocytopenia, among others (20). PE predisposes women to cardiovascular complications and exerts direct consequences on the offspring, including intrauterine growth restriction and cardiometabolic disease later in life (20). The etiology of PE remains unknown. However, because the only known cure is delivery of both the fetus and placenta, it is widely accepted that abnormal placentation plays a causal role in PE. A number of preexisting maternal conditions are risk factors for PE, including obesity. This review highlights one proposed mechanism whereby adipose tissue, rich in inflammatory mediators and complement proteins, contributes to altered placental angiogenesis and development in PE.

PREGNANCY, PREECLAMPSIA, AND ANGIOGENESIS

Normal placental development is essential for pregnancy success. First, embryo implantation is followed by trophoblast cell proliferation and differentiation before invasion and remodeling of maternal spiral arteries (27). To support the developing placenta, the fetoplacental unit then produces angiogenic factors including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) (19). Once the placenta is functional, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), an antiangiogenic factor and a VEGF antagonist, is produced to modulate VEGF activity (13, 21). A delicate balance of pro- and antiangiogenic factors is necessary in a healthy pregnancy. Furthermore, tight regulation of the maternal immune system, including complement system activation at the maternal-fetal interface, is needed to establish and maintain pregnancy (3). Inadequate trophoblast remodeling of spiral arteries, a key feature of PE, is believed to result from perturbations in the maternal immune response and placental angiogenesis (16). The exact mechanisms causing impaired placentation in PE have yet to be elucidated, but several risk factors such as chronic hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, and obesity have been described (1).

OBESITY AND PREECLAMPSIA

Increasing body mass index (BMI) is positively associated with an increased risk of PE (2, 35). Women with a prepregnancy BMI of 35 kg/m2 or above have a 30% increased risk of developing PE (38). This relationship is confirmed by evidence illustrating that bariatric surgery done to decrease obesity can reduce the incidence of PE (8). The association between obesity and PE is concerning considering that obesity is rapidly rising among women throughout much of the world, especially in North America and Europe (37). Obesity is characterized by expansion of adipose tissue (fat) in the body. Furthermore, maternal obesity along with circulating factors, such as nonesterified fatty acids, may contribute to excess lipid accumulation in the placenta (14, 36). This can interfere with placental development, including trophoblast invasion and angiogenesis as well as nutrient transport between mother and fetus, resulting in increased oxidative stress and inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface (36). These placental injuries often characterize PE pregnancies. The localization of many proinflammatory factors, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6, to adipose tissue led to the understanding that obesity presents a state of low-grade systemic inflammation (7). The connection between maternal obesity and PE is hypothesized to involve immune cells within the mother’s adipose tissue and in the placenta contributing to impaired placentation (11).

COMPLEMENT ACTIVATION AND OBESITY IN PREECLAMPSIA

The complement system has been implicated as a link between excess adipose tissue and PE (4, 32). Complement components increase with obesity and are positively correlated with BMI as well as subcutaneous, visceral, and total fat area, while decreasing with weight loss (30). The complement system consists of over 50 well-regulated proteins generated primarily by the liver, but also by other organs and tissues. The complement system can therefore be activated systemically in circulation or locally within specific tissue environments, i.e., adipose tissue (4, 22, 32). Previously, complement activity was thought to primarily exist in extracellular compartments. Current research, however, indicates that the complement system is also active intracellularly. This novel intracellular complement system has been termed the “complosome” (12, 41). It is hypothesized that complement proteins are responsible for protecting the body from pathogens. More recently, it has been shown that complement proteins are involved in many diverse physiological processes such as clearance of apoptotic cells and cellular debris, and regulating humoral and innate immune responses (39). The complement cascade is activated through three primary pathways described as alternative, lectin, and classical pathways. Although each pathway contains distinct proteins that respond to different stimuli and activate the complement cascade, all pathways eventually converge at complement component 3 (C3). C3 produces effector molecules including the membrane attack complex and anaphylatoxins C3a and complement fragment 5 (C5)a. These fragments act via G protein-coupled receptors C3a receptor (C3aR) and C5a receptor (C5aR), respectively (39).

A tightly regulated immune system is essential to placentation because the embryo presents with both maternal (self) and paternal (nonself) antigens (29). The complement system is no exception to this tight regulation; it must be downregulated to allow adequate placentation, yet simultaneously activated to protect the mother and fetus from foreign pathogens (10). Serum concentrations of C3 have been shown to be upregulated in pregnancies affected by PE, while C4 is reduced (17). Furthermore, single nuclear polymorphisms in the C3 gene of women may be predictive for determining PE risk (23). The source of the complement dysregulation is under current investigation. Concentrations of complement components, specifically adipsin (Complement Factor D) in serum or urine detected early in pregnancy have been suggested to identify patients susceptible for developing PE (24, 25, 40). Adipsin is primarily produced by adipocytes (30). Women with increased serum concentrations of complement fragments Bb and C3a combined with obesity were most likely to develop PE compared with those with either only obesity or higher levels of circulating Bb and C3a, or neither (24, 25). This observation highlighted the potential interaction between adiposity and the complement system in the pathogenesis of PE with excess adipose tissue being a source of the increased complement proteins noted in pregnancies affected by PE. Interestingly, C3aR mRNA is highly expressed in adipose tissue of C57BL/6 mice, and this expression has been shown to significantly increase when mice are put on a high-fat diet (28). This illustrates a role for the complement system in adipose tissue signaling during diet induced obesity. Interestingly, Kestlerová et al. (17) reported 42% of the women with PE were obese with a BMI >30. While these findings provide strong evidence for obesity-mediated complement activation in PE, further studies are needed to elucidate the precise mechanism.

COMPLEMENT AND ANGIOGENESIS

Visceral white adipose tissue of the intra-abdominal depot (the central fat compartment) may contribute to fat accumulation at the placenta and could be the source of increased complement in PE pregnancies (5, 36). Complement dysregulation has been hypothesized to influence the development of PE via interactions with angiogenic factors localized at the maternal-fetal interface (11). An angiogenic imbalance both in the placenta and in maternal circulation is a hallmark of PE (6, 33). In healthy pregnancies, an increase in antiangiogenic factors is observed from ~33 wk onward (21). Whereas in PE, there is an increase in circulating sFlt-1 with a corresponding decrease in the proangiogenic factor PlGF beginning at 20 wk (21). sFlt-1 binds free VEGF and PlGF, rendering them inactive, thus producing an apparent systemic angiogenic imbalance in the PE mother early in pregnancy (21, 31). This phenomenon may be influenced by the complement system.

Compared with healthy pregnant women, increased localization of the complement component C5a was evident at the maternal-fetal interface in women with PE (26). Moreover, C5a increased the expression of antiangiogenic factors including TNF-α and sFlt-1 and, in tandem, decreased expression of proangiogenic PlGF and anti-inflammatory IL-10 in trophoblast cells, all of which have been implicated as key players in PE. In this study, C5a was predominantly localized in macrophages, while the C5aR was found on trophoblasts (26). These data suggest that macrophage infiltration promotes complement factor C5a binding to its receptor on trophoblast cells, thus restricting adequate trophoblast invasion and angiogenesis, thereby contributing to the etiology of PE. In support of this mechanism, in a murine model of hypoxia-induced retinal vascularization, it was shown that C5a will polarize macrophages to produce the antiangiogenic factors sFlt-1 and TNF-α (18). The relationship between C5a and angiogenic dysregulation was further confirmed by Girardi and colleagues (11), who demonstrated that C5a could induce monocytes to produce increased sFlt-1, thus decreasing the VEGF required for placental angiogenesis. Furthermore, inhibition of C3 activation early in pregnancy improved outcomes in a mouse model of spontaneous PE, including fetal loss and growth restriction, as well as increasing placental weight and restoration of spiral artery remodeling (9). The maternal hypertensive phenotype was not assessed with complement inhibition in this study; however, this outcome is important in understanding the relationship between complement inhibition and PE. The therapeutic potential of complement inhibition is being investigated in a number of animal models of adverse pregnancy outcomes and holds promise for treating women with PE (34).

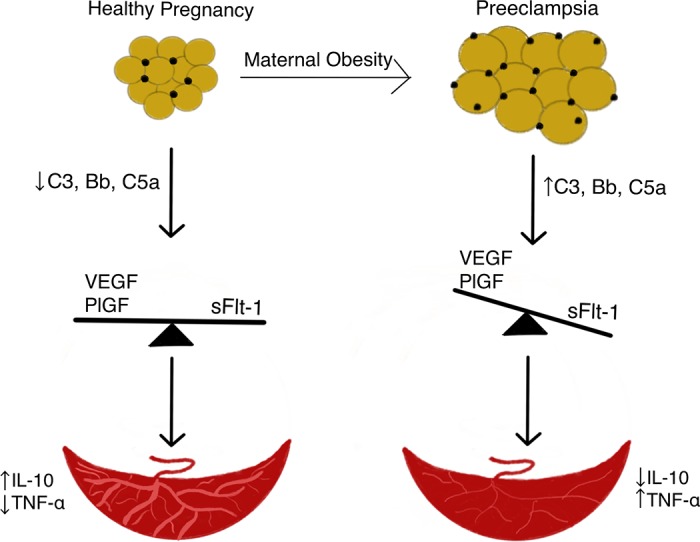

Maternal obesity in pregnancy is characterized by increased complement activation, which is hypothesized to mediate an angiogenic imbalance at the maternal-fetal interface, accompanying an increased development of PE (Fig. 1). It is critical to understand the source of complement dysregulation as well as the mechanism by which increased complement fragments and components contribute to the placental injury characteristic of PE pregnancies. Future studies should investigate whether visceral adipose tissue proximal to the female reproductive tract could be a source of complement components infiltrating into the maternal-fetal interface, and whether decreasing the maternal adipose tissue before or during pregnancy could prevent PE in women with obesity.

Fig. 1.

Working hypothesis linking maternal obesity and preeclampsia. We hypothesize that excess maternal adipose tissue proximal to the reproductive tract is the source of increased complement components and fragments (C3, Bb, C5a) observed in preeclamptic pregnancies. These complement proteins, found in maternal circulation and placenta, may promote increased production of antiangiogenic factors including soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1), which in turn, decreases proangiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF), creating an angiogenic imbalance. This imbalance results in placental injury, leading to decreased blood flow to the placenta concomitant with alterations in placental cytokines, interleukin (IL)-10 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, before the presentation of preeclampsia. Yellow circles represent adipocytes. Black circles represent adipose tissue immune cells.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.N.O. and J.L.S. performed experiments; K.N.O. and J.L.S. analyzed data; K.N.O., L.M.R., and J.L.S. interpreted results of experiments; K.N.O. prepared figures; K.N.O. drafted manuscript; K.N.O., L.M.R., and J.L.S. edited and revised manuscript; K.N.O., L.M.R., and J.L.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, Ray JG; High Risk of Pre-eclampsia Identification Group . Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ 353: i1753, 2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N, Roberts JM. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Ann Epidemiol 15: 475–482, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulla R, Agostinis C, Bossi F, Rizzi L, Debeus A, Tripodo C, Radillo O, De Seta F, Ghebrehiwet B, Tedesco F. Decidual endothelial cells express surface-bound C1q as a molecular bridge between endovascular trophoblast and decidual endothelium. Mol Immunol 45: 2629–2640, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choy LN, Rosen BS, Spiegelman BM. Adipsin and an endogenous pathway of complement from adipose cells. J Biol Chem 267: 12736–12741, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chusyd DE, Wang D, Huffman DM, Nagy TR. Relationships between Rodent White Adipose Fat Pads and Human White Adipose Fat Depots. Front Nutr 3: 10, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2016.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper JC, Sharkey AM, Charnock-Jones DS, Palmer CR, Smith SK. VEGF mRNA levels in placentae from pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 103: 1191–1196, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115: 911–919, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galazis N, Docheva N, Simillis C, Nicolaides KH. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in women undergoing bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 181: 45–53, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelber SE, Brent E, Redecha P, Perino G, Tomlinson S, Davisson RL, Salmon JE. Prevention of Defective Placentation and Pregnancy Loss by Blocking Innate Immune Pathways in a Syngeneic Model of Placental Insufficiency. J Immunol 195: 1129–1138, 2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girardi G, Prohászka Z, Bulla R, Tedesco F, Scherjon S. Complement activation in animal and human pregnancies as a model for immunological recognition. Mol Immunol 48: 1621–1630, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girardi G, Yarilin D, Thurman JM, Holers VM, Salmon JE. Complement activation induces dysregulation of angiogenic factors and causes fetal rejection and growth restriction. J Exp Med 203: 2165–2175, 2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajishengallis G, Reis ES, Mastellos DC, Ricklin D, Lambris JD. Novel mechanisms and functions of complement. Nat Immunol 18: 1288–1298, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ni.3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Y, Smith SK, Day KA, Clark DE, Licence DR, Charnock-Jones DS. Alternative splicing of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-R1 (FLT-1) pre-mRNA is important for the regulation of VEGF activity. Mol Endocrinol 13: 537–545, 1999. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.4.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvie E, Hauguel-de-Mouzon S, Nelson SM, Sattar N, Catalano PM, Freeman DJ. Lipotoxicity in obese pregnancy and its potential role in adverse pregnancy outcome and obesity in the offspring. Clin Sci (Lond) 119: 123–129, 2010. doi: 10.1042/CS20090640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeyabalan A. Epidemiology of preeclampsia: impact of obesity. Nutr Rev 71, Suppl 1: S18–S25, 2013. doi: 10.1111/nure.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji L, Brkić J, Liu M, Fu G, Peng C, Wang YL. Placental trophoblast cell differentiation: physiological regulation and pathological relevance to preeclampsia. Mol Aspects Med 34: 981–1023, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kestlerová A, Feyereisl J, Frisová V, Měchurová A, Šůla K, Zima T, Běláček J, Madar J. Immunological and biochemical markers in preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 96: 90–94, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer HF, Chung KJ, Orlova VV, Choi EY, Kaul S, Kruhlak MJ, Alatsatianos M, DeAngelis RA, Roche PA, Magotti P, Li X, Economopoulou M, Rafail S, Lambris JD, Chavakis T. Complement-mediated inhibition of neovascularization reveals a point of convergence between innate immunity and angiogenesis. Blood 116: 4395–4403, 2010. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lash GE, Naruse K, Innes BA, Robson SC, Searle RF, Bulmer JN. Secretion of angiogenic growth factors by villous cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast in early human pregnancy. Placenta 31: 545–548, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leeman L, Dresang LT, Fontaine P. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 93: 121–127, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 350: 672–683, 2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li K, Sacks SH, Zhou W. The relative importance of local and systemic complement production in ischaemia, transplantation and other pathologies. Mol Immunol 44: 3866–3874, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lokki AI, Kaartokallio T, Holmberg V, Onkamo P, Koskinen LLE, Saavalainen P, Heinonen S, Kajantie E, Kere J, Kivinen K, Pouta A, Villa PM, Hiltunen L, Laivuori H, Meri S. Analysis of Complement C3 Gene Reveals Susceptibility to Severe Preeclampsia. Front Immunol 8: 589, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch AM, Eckel RH, Murphy JR, Gibbs RS, West NA, Giclas PC, Salmon JE, Holers VM. Prepregnancy obesity and complement system activation in early pregnancy and the subsequent development of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 206: 428.e1–428.e8, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynch AM, Murphy JR, Byers T, Gibbs RS, Neville MC, Giclas PC, Salmon JE, Holers VM. Alternative complement pathway activation fragment Bb in early pregnancy as a predictor of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198: 385.e1–385.e9, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Kong LR, Ge Q, Lu YY, Hong MN, Zhang Y, Ruan CC, Gao PJ. Complement 5a-mediated trophoblasts dysfunction is involved in the development of pre-eclampsia. J Cell Mol Med 22: 1034–1046, 2018. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malassiné A, Frendo JL, Evain-Brion D. A comparison of placental development and endocrine functions between the human and mouse model. Hum Reprod Update 9: 531–539, 2003. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mamane Y, Chung Chan C, Lavallee G, Morin N, Xu LJ, Huang J, Gordon R, Thomas W, Lamb J, Schadt EE, Kennedy BP, Mancini JA. The C3a anaphylatoxin receptor is a key mediator of insulin resistance and functions by modulating adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and activation. Diabetes 58: 2006–2017, 2009. doi: 10.2337/db09-0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moffett A, Colucci F. Uterine NK cells: active regulators at the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest 124: 1872–1879, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI68107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreno-Navarrete JM, Fernández-Real JM. The complement system is dysfunctional in metabolic disease: Evidences in plasma and adipose tissue from obese and insulin resistant subjects. Semin Cell Dev Biol 85: 164–172, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikuei P, Malekzadeh K, Rajaei M, Nejatizadeh A, Ghasemi N. The imbalance in expression of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors as candidate predictive biomarker in preeclampsia. Iran J Reprod Med 13: 251–262, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson B, Hamad OA, Ahlström H, Kullberg J, Johansson L, Lindhagen L, Haenni A, Ekdahl KN, Lind L. C3 and C4 are strongly related to adipose tissue variables and cardiovascular risk factors. Eur J Clin Invest 44: 587–596, 2014. doi: 10.1111/eci.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polliotti BM, Fry AG, Saller DN, Mooney RA, Cox C, Miller RK. Second-trimester maternal serum placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor for predicting severe, early-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 101: 1266–1274, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regal JF, Burwick RM, Fleming SD. The Complement System and Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep 19: 87, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0784-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts JM, Bodnar LM, Patrick TE, Powers RW. The Role of Obesity in Preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 1: 6–16, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saben J, Lindsey F, Zhong Y, Thakali K, Badger TM, Andres A, Gomez-Acevedo H, Shankar K. Maternal obesity is associated with a lipotoxic placental environment. Placenta 35: 171–177, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann Nutr Metab 66, Suppl 2: 7–12, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000375143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spradley FT, Palei AC, Granger JP. Immune Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Preeclampsia. Biomolecules 5: 3142–3176, 2015. doi: 10.3390/biom5043142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varela JC, Tomlinson S. Complement: an overview for the clinician. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 29: 409–427, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang T, Zhou R, Gao L, Wang Y, Song C, Gong Y, Jia J, Xiong W, Dai L, Zhang L, Hu H. Elevation of urinary adipsin in preeclampsia: correlation with urine protein concentration and the potential use for a rapid diagnostic test. Hypertension 64: 846–851, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West EE, Kolev M, Kemper C. Complement and the Regulation of T Cell Responses. Annu Rev Immunol 36: 309–338, 2018. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]