Abstract

Structural proteins like collagen and elastin are major constituents of the extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM degradation and remodeling in diseases significantly impact the microorganization of these structural proteins. Therefore, tracking the changes of collagen and elastin fiber morphological features within ECM impacted by disease progression could provide valuable insight into pathological processes such as tissue fibrosis and atherosclerosis. Benefiting from its intrinsic high-resolution imaging power and superior biochemical specificity, nonlinear optical microscopy (NLOM) is capable of providing information critical to the understanding of ECM remodeling. In this study, alterations of structural fibrillar proteins such as collagen and elastin in arteries excised from atherosclerotic rabbits were assessed by the combination of NLOM images and textural analysis methods such as fractal dimension (FD) and directional analysis (DA). FD and DA were tested for their performance in tracking the changes of extracellular elastin and fibrillar collagen remodeling resulting from atherosclerosis progression/aging. Although other methods of image analysis to study the organization of elastin and collagen structures have been reported, the simplified calculations of FD and DA presented in this work prove that they are viable strategies for extracting and analyzing fiber-related morphology from disease-impacted tissues. Furthermore, this study also demonstrates the potential utility of FD and DA in studying ECM remodeling caused by other pathological processes such as respiratory diseases, several skin conditions, or even cancer.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Textural analyses such as fractal dimension (FD) and directional analysis (DA) are straightforward and computationally viable strategies to extract fiber-related morphological data from optical images. Therefore, objective, quantitative, and automated characterization of protein fiber morphology in extracellular matrix can be realized by using these methods in combination with digital imaging techniques such as nonlinear optical microscopy (NLOM), a highly effective visualization tool for fibrillar collagen and elastic network. Combining FD and DA with NLOM is an innovative approach to track alterations of structural fibrillar proteins. The results illustrated in this study not only prove the effectiveness of FD and DA methods in extracellular protein characterization but also demonstrate their potential value in clinical and basic biomedical research where protein microstructure characterization is critical.

Keywords: collagen, directionality, elastic fiber, fractal dimension, second-harmonic generation, two-photon excited fluorescence

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 15 years, nonlinear optical microscopy (NLOM) has emerged as a powerful research tool in biology (26, 43, 49). Based on the physics of nonlinear light-matter interactions, and using these interactions as contrast mechanisms for cellular and tissue imaging investigations, NLOM has acquired the reputation of an excellent optical tool for answering multiple biological questions (7, 30, 49). The general consensus is that the nonlinear optical techniques provide additional biochemical information compared with, for example, visible light microscopy (32).

Among many possible applications of NLOM in biomedicine, several groups have been focusing on the application of NLOM to better understanding of cardiovascular diseases (9, 14, 15, 18, 47, 50). Lilledahl et al. (20, 21) studied collagen fiber accumulation in the fibrous cap of atherosclerotic plaque through two-photon emission fluorescence (TPEF) and second-harmonic generation (SHG) images. Megens et al. (25) applied TPEF microscopy to image arteries labeled with specific fluorescent markers for collagen, inflammatory cells, cell nuclei, and lipids to gain insight into the distribution of collagen and its association with inflammatory cells during plaque formation. Doras et al. (6) performed nonlinear optical image reconstructions, as well as polarization state analysis inside an artery wall affected by atherosclerosis, to investigate the changes in collagen structure. These studies, combined with the work carried out by groups aiming to model and understand the role of different structures within the arterial wall (2, 24, 37), have been key to providing novel insights regarding the vasculature remodeling and its role in arterial homeostasis, including adaptations to altered hemodynamics, injury, and disease.

Collagen and elastin organization plays a crucial role in extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, and alterations of the underlying mechanical principles of the healthy arterial wall (for example, changes in wall ECM constituents) are believed to have implications for arterial disease and degeneration (29). Through improved imaging of ECM proteins, at a higher resolution and superior biochemical specificity than obtained by histological stains, NLOM can provide information useful in the understanding of remodeling associated with disease and aging. Such information can also be incorporated into structurally based constitutive models in future diagnostic interventions (31). To this end, NLOM is used to track alterations of structural fibrillar proteins, illustrated in this work by what is occurring in the arterial wall caused by aging and/or atherosclerotic progression.

Although other methods of image analysis to study the organization of elastin and collagen structures have been reported (4, 48), the simplified calculations of fractal dimension (FD) and directional analysis (DA) are considered a more accessible and computationally viable strategy to extract fiber-related morphological information from optical images. The methods presented in this work are evaluated on the basis of their performance in differentiating between various groups of TPEF and SHG images that show distinctly different elastin and collagen structural features reflecting hallmarks of ECM alterations in the blood vessel wall of atherosclerotic animals. These methods were also tested for their performance in tracking the changes of extracellular elastin and fibrillar collagen remodeling along atherosclerosis progression and aging. Ultimately, we aim to present a strategy easily accessible for evaluation of the progression of atherosclerosis and age-related changes in the arterial wall, based on in vitro experiments. These methods could eventually be incorporated into image classification strategies that can be valuable in other biomedical applications where characterization of structural proteins in ECM is critical.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Arterial tissue preparation.

All animal experiments conformed to the guidelines set out by the Canadian Council on Animal Care regarding the care and use of experimental animals and were reviewed and approved by the local Animal Care Committee of the National Research Council of Canada. The animal model used in this study was the myocardial infarction-prone Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbit. This rabbit model spontaneously develops atherosclerotic plaques because of a hereditary defect in LDL processing (13, 39). In total, 21 rabbits were used in this study, including 6 rabbits aged 0–4 mo, 6 rabbits aged 6–12 mo, 5 rabbits aged 14–16 mo, and 4 rabbits aged 18–27 mo. The animals were euthanized by intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (120 mg/kg). Heparin (1,000 U/kg) was also included in the injection to prevent blood clotting. EMLA cream was applied to the injection site 10–15 min before injections. Eight regions of interest (ROIs) per animal were identified along the aorta. At each ROI, an image mosaic consisting of four SHG/TPEF images (2 × 2 format) measuring 500 μm × 500 μm per image was generated to cover an area of ~1 mm × 1 mm. One hundred fifteen image mosaics (panels) were used in the analysis, and they are divided as follows: 38 from group A (young, 0–4 mo old), 36 from group B (middle-aged I, 6–12 mo old), 23 from group C (middle-aged II, 14–16 mo old), and 18 from group D (old, 18–27 mo old). The excised aorta was dissected from the ascending aorta to the external iliac artery and then rinsed in heparinized saline. The exterior aorta was subdivided into 60- to 80-mm sections that were cut open longitudinally, exposing the luminal surface. The samples were placed in petri dishes with the luminal surface facing up on a moist surface, and hydration was maintained throughout the measurements by periodic application of PBS. Each excised aorta segment was surgically removed, with anatomical “landmarks” kept consistent for all animals. For the segment named “aorta arch,” the whole arch was included; the “thoracic artery” segment included the straight segment following the arch, ending before the main pulmonary arteries; the “abdominal artery” consisted of primarily the segment below the pulmonary arteries down past the kidney arteries’ bilateral bifurcation; finally, the “external iliac aorta” was once again a straight segment, being the last portion of the aorta to be analyzed. Each segment had two specific points predefined as ROIs to be imaged, to account for the intrinsic biological variability. ROIs were identified before TPEF/SHG image measurements. More procedural details including the microscope setup can be found in previous work (15).

TPEF and SHG microscopic imaging.

An in-house, custom-built multiphoton microscope was used for tissue imaging and was described previously (15, 27). A Ti:sapphire oscillator (Tsunami, Spectra-Physics) with a center wavelength at 800 nm and a pulse width of 100 fs was used as the laser source for generating TPEF and SHG signals. The laser pulses were first passed through a Faraday isolator (Newport) and precompressed with a pair of chirped mirrors (LAYERTEC) to compensate for the positive pulse chirping introduced by the microscope optics. After passing through the various lenses and polarizing optics, the pulses were sent into the microscope assembly, where a non-descanned modular-type photomultiplier tube detector (Hamamatsu) was used for signal detection in either the epidirection or the forward direction. The laser pulses were focused onto a sample through a ×20, 0.75 NA infinity-corrected air objective lens (Olympus). Typically, 25 mW of laser power (measured after the ×20 air objective lens) was used for imaging. ScanImage software (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) was used for laser scanning control and image acquisition. During image acquisition all arterial tissue samples were placed on the stage in such a way that their orientation remained the same according to the blood flow direction (from left to right). The depth-related analysis was performed by moving the translational stage up vertically to image the tunica intima and then into the tunica media layers. The first set of images were acquired from just beneath the luminal surface, within ~5 μm, followed by imaging at depths of ~18 μm, ~25 μm (midpoint of tunica intima), ~30 μm, and ~45 μm, in order to cover the entire tunica intima layer and slightly past the internal elastic lamina (IEL). These five depths are referred as d1–d5 in Fig. 1.

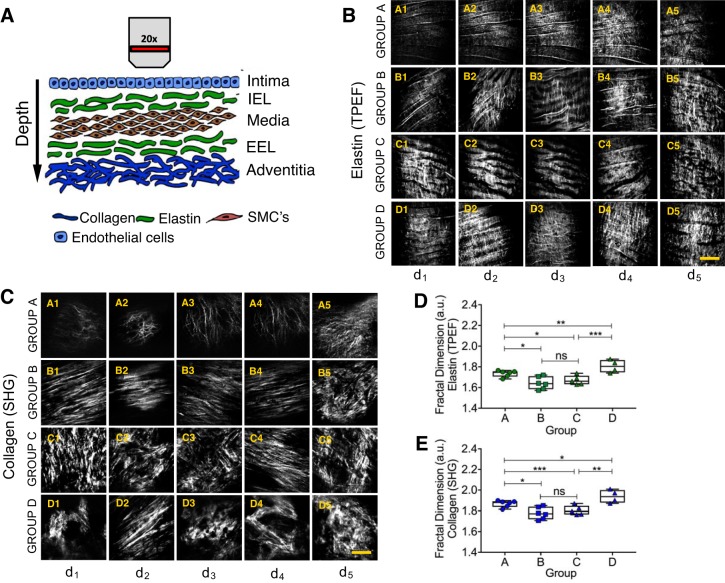

Fig. 1.

A: schematic illustration of nonlinear optical microscopy (NLOM) image acquisition. The images were acquired at certain depths (5 μm, 18 μm, 24 μm, 30 μm, and >40 μm), aiming to document the whole extent of the tunica intima. EEL, external elastic lamina; IEL, internal elastic lamina; SMCs, smooth muscle cells. B and C: examples of 2-photon emission fluorescence (TPEF; B) and second-harmonic generation (SHG; C) images acquired from the regions along the aorta of myocardial infarction-prone Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Images were classified into groups A–D, according to the rabbits’ age: group A: 0–4 mo old; group B: 6–12 mo old; group C: 14–16 mo old; group D: 18–27 mo old. Each group of images has its own characteristic morphological features such as shape, density, and organization. Images show the IEL. Scale bars, 50 μm. D and E: fractal dimension values [arbitrary units (a.u.)] for TPEF (D) and SHG (E) images acquired in regions along the aorta. The orientation of the vessels during image acquisition was kept constant, according to the blood flow direction (from left to right). Total number of images used: 460 for TPEF and 460 for SHG; 115 panels from 20 individual rabbits were considered, and images were taken from 8 different locations per rabbit. Each point shown represents data from 1 individual rabbit. Depth (d)1: ~5 μm; d2: ~18 μm; d3: ~24 μm; d4: ~30 μm; d5: >40 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. ns, Not significant. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data was applied.

Image processing.

Image postprocessing was performed in Fiji software (36). Image background correction, intensity normalization, and calculation of various image texture parameters were carried out with MATLAB 7.5, according to the procedure outlined previously (28).

Fractal dimension.

Several approaches have been developed to estimate the FD of an image. Of the wide variety of methods, the box counting method is one of the most widely used (34), as it can be applied to patterns with or without self-similarity. The box counting method partitions the image space into square boxes of equal size. The box covers the image space of the function or pattern of interest, and the number of boxes that contain at least one pixel of the function is counted. The process is repeated with different box sizes. The FD is obtained from the slope of the best straight-line fitting to the graph plotting the log of the number of boxes counted (N) versus the log of the magnification index (1/r) for every stage of partitioning. For example, an image measuring M × M pixel in size is scaled down to s × s, where 1 < s < M/2 and s is an integer. Then, r = sM. Fractal dimension D is given by

| (1) |

The FracLac plug-in for Fiji was used to perform the box count for the fractal analysis. Before the FD of each image was extracted, the segmentation of fiberlike structures from TPEF and SHG images was performed with a Hessian-based tubeness filter (34). This filter determines how “tubelike” a pixel is by convolving the image with a spherical Gaussian kernel with standard deviation alpha, computing the Hessian matrix at each pixel, and computing a “tubeness” metric from the Hessian eigenvalues. The sensitivity of the tubeness filter to tubular structures of varying radii can be tuned by varying alpha. The definition of alpha value used in the fractal method was performed based on the definition proposed by Yen et al. (47a) and Sezgin and Sankur (37a). Several alpha values were tested based on a maximum correlation criterion, where the discrepancy between the thresholded and original images as well as the number of bits required to represent the thresholded image were defined. A cost function that takes both factors into account was defined as the “alpha number,” and we automatically optimized it with the aim of keeping a reasonable balance between the real structures shown in the images and what is being highlighted after applying the threshold. The choice of alpha is important and must be tailored accordingly to the application in question, and for this study alpha = 1.0 was the optimum value for analyzing elastic fibers in the arteries. ROIs were identified before TPEF imaging. More details about this Fiji plug-in can be found elsewhere (36).

Directional analysis.

Another aspect of fibers that can be evaluated is their orientation. Oriented linear patterns are common phenomena in nature and are an important class in image analysis. DA is used to analyze TPEF images with the aim of elucidating the preferred orientation of structures present in the input image. It computes a histogram indicating the number of structures oriented in a given direction. Images with completely isotropic content are expected to give a flat histogram, whereas images in which there is a preferred orientation are expected to give a histogram with a peak for that orientation. Angles are reported in their common mathematical sense: 0° indicates the east direction, which points in the direction of the blood flow, and direction moves counterclockwise with increasing angles. This analysis is based on Liu’s work (22), which served as a base for the development of the Directionality plug-in for Fiji. Liu introduced a new method for linear pattern extraction and DA based on Fourier spectrum analysis. For a square image, structures with a preferred orientation generate a periodic pattern at +90° orientation in the Fourier transform of the image compared with the direction of the objects in the input image. Then the image is chopped into square pieces, and their Fourier power spectra are computed. The latter are analyzed in polar coordinates, and the power is measured for each angle with the spatial filters proposed in Ref. 22.

Statistical analysis.

A Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used. FD and fiber DA were analyzed between groups by Mann-Whitney test. All statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism version 5.04 (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Fiber visualization using TPEF and SHG microscopy.

Images of the aorta were taken from the luminal surface to a depth of ~45 μm beneath the tissue surface, at different focal planes (5 μm, 18 μm, 24 μm, 30 μm, and >40 μm) as noted in Fig. 1. Examples of the elastin fibers of the aorta are presented (TPEF images) in Fig. 1B. The IEL is clearly visible, ranging from its most external surfaces, closer to the lumen, to its deepest portion, adjacent to the media layer. Examples of collagen fibers (SHG images) acquired at similar depths are shown in Fig. 1C. Images acquired from a newborn rabbit, such as those in images A1–A5 in Fig. 1, B and C, show very thin fiberlike yet disorganized structures. As the rabbits age, the elastic layer becomes better developed, as shown in images B1–B5 of Fig. 1, B and C, evidenced by a band-shaped IEL.

Some of the changes caused by atherosclerosis can be noticed by comparing images B1–B5 with images C1–C5 in Fig. 1, B and C. These changes were likely caused by reduced vessel compliance as a result of progressive and diffuse fibrosis of the vessel walls (23). In addition, denser accumulation of structures corresponding with a loss of fiber organization is observed in images D1–D5 in Fig. 1, B and C, which are taken from a 27-mo-old rabbit, near the end of its natural life.

Alterations in elastic and collagen fiber morphology.

FD analysis of TPEF and SHG images provides insights associated with changes within the structure of the arterial wall. The FD changes as the elastic fibers start to degrade and the collagen fibers start to accumulate because of aging and/or atherosclerosis progression. The values of FD for elastin and collagen structures are presented in Fig. 1, D and E, respectively. Group A, including images collected from young animals (0–4 mo old), is characterized by a higher FD than that observed for group B (6–12 mo old), which shows the lowest FD values of all groups.

Atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling analysis using FD.

We also evaluated the vascular remodeling as a response to atherosclerosis development. It is already known that certain locations along the aorta are more prone to plaque development than others (8, 16, 38, 40, 44). At these locations the rate and pattern of blood flow are altered, thus affecting local hemodynamics. As a result, changes in plaque development were observed (6). In Fig. 2A, different patterns of tunica intima and IEL emerge at different locations of the aorta, illustrating how the elastic layer is affected by changes in blood flow and how collagen deposition changes depending on the location.

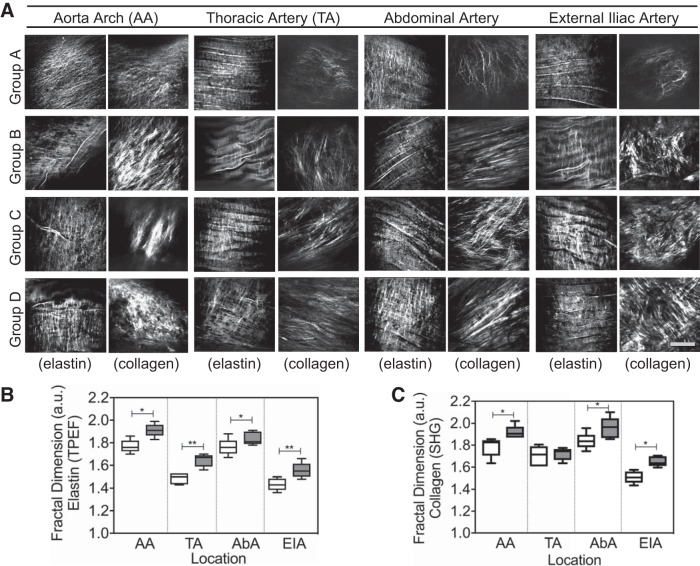

Fig. 2.

A: examples of 2-photon emission fluorescence (TPEF) and second-harmonic generation (SHG) images from different locations along the aorta. Images are labeled with the corresponding aorta segment, rabbit age group, and type of image (collagen, SHG or elastin, TPEF). Group A: 0–4 mo old; group B: 6–12 mo old; group C: 14–16 mo old; group D: 18–27 mo old. Images from different age groups show degradation of the vessel elastic layer and collagen deposition. The orientation of the vessels during image acquisition was kept constant by aligning it with the blood flow direction (from left to right). Scale bar, 50 μm. B and C: fractal dimension values [arbitrary units (a.u.)] obtained from TPEF (B) and SHG (C) images acquired from different locations along the aorta. White boxes represent the data for young rabbits (age <10 mo) in each aorta region. Gray bars represent the data for old rabbits (age >18 mo) in each aorta region. AA, aorta arch; AbA, abdominal artery; a.u., arbitrary unit; EIA, external iliac artery; TA, thoracic artery. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data was applied.

By applying FD analysis on TPEF and SHG images acquired at the center portion of the IEL, or ~25 ± 3 μm beneath the surface, it was possible to quantitatively track the IEL differences along the aorta. From Fig. 2, B and C, we can observe that FD values were the highest in the aortic arch (AA), followed by the abdominal artery region (AbA). These two regions have been demonstrated as the most critical locations for plaque development (8, 17, 38).

Finally, we tested whether FD analysis would be able to distinguish regions affected by atherosclerotic plaques from healthy segments on the same aorta from the same animal. Results showed significant increase of the FD scores for both elastin and collagen fiber organization in the plaque regions on the same aorta, as depicted in Fig. 3, A and B, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Comparison between control (healthy) regions and atherosclerotic plaques from the same animal. A and B: elastic (A) and collagen (B) fibers present higher fractal dimension values [arbitrary units (a.u.)] indicating fiber disruption. Group A: 0–4 mo old; group B: 6–12 mo old; group C: 14–16 mo old; group D: 18–27 mo old. C and D: different locations along the aorta also present distinct fractal dimensions for both elastin (C) and collagen (D) fibers. AA, aorta arch; AbA, abdominal artery; EIA, external iliac artery; SHG, second-harmonic generation; TA, thoracic artery; TPEF, 2-photon emission fluorescence. White boxes represent the data obtained from healthy portion of aorta in each specific location (control). Gray boxes represent the data obtained from atherosclerotic plaques located in each specific location. Circles represent means, and error bars denote SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data was applied.

Additionally, Fig. 3, C and D, show how the FD analysis tracks the morphological changes at different locations along the aorta, based on mean FD scores obtained from all animals in the study. Similar to our findings obtained from the age-correlated data, healthy segments of the artery consistently present statistically significant lower FD scores than regions affected by atherosclerotic plaque. Data show that the elastic fibers are more disrupted at the AA and AbA locations compared with thoracic artery (TA) and external iliac artery (EIA) locations. This observation matches well with the age-correlated data presented in Fig. 2. However, changes seen in collagen fibers’ FD scores did not present the same level of correlation regarding FD score changes when simply comparing plaque and control regions. Contrary to what the age-correlated data indicate in Fig. 2C, the collagen FD score at the EIA location was slightly higher than that for the AbA location.

Fiber directional analysis.

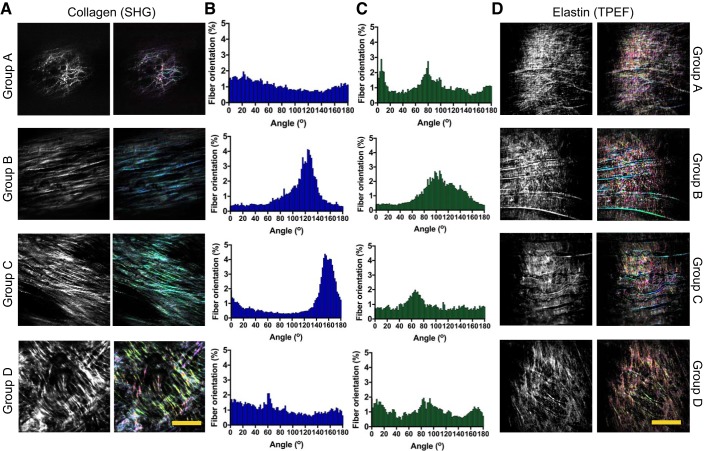

The directionality of elastin and collagen fibers in TPEF and SHG images of rabbit aortas of different ages was also assessed. TPEF and SHG images from the thoracic region (TA) were used in this analysis, as it was shown to be the most anatomically stable region among all animals regarding the degree of atherosclerosis progression in this study. Representative images are presented in Fig. 4, A and D. As the rabbit ages, significant changes in the fiber orientation were detected as shown in the directionality histograms in Fig. 4, B and C. The orientations of fibers located in the IEL of both young and old rabbit groups (Fig. 4, B and C, respectively) have been found to be similar and are close to Gaussian distributions. The distribution presented in the images of young animals, however, is broader than that found for TPEF and SHG images of old animals.

Fig. 4.

A: examples of second-harmonic generation (SHG) images showing the collagen deposition on the arterial wall of rabbits with different age groups: group A (newborn rabbit), group B (6 mo old); group C (16 mo old), and group D (27 mo old). As the fibers are remodeled, the orientation changes. B and C: directionality map for SHG images (B) and for 2-photon emission fluorescence (TPEF) images (C). D: examples of TPEF images showing elastic fiber changes on the arterial wall of rabbits with different ages. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Distinguishing atherosclerotic lesions.

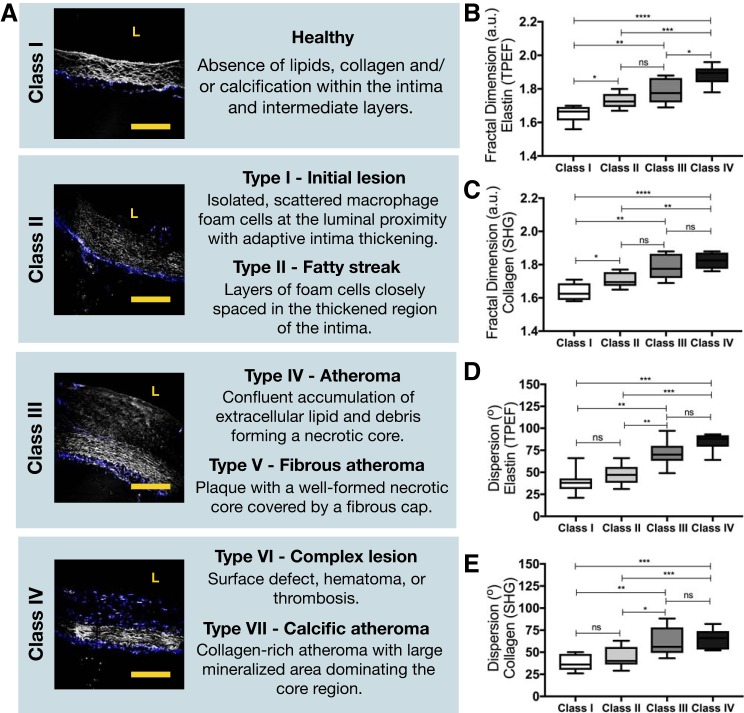

It was demonstrated that our approach of combining FD and DA has a strong potential to distinguish the severity of atherosclerotic plaque. The American College of Cardiology-American Heart Association definition for atherosclerotic lesions is the most widely used classification system, defining lesion categories on the basis of their histological features. This definition can be visually illustrated with images obtained from this study and is summarized in Fig. 5A. Despite the age of the rabbits and the location of the lesions along the aorta, FD of collagen and elastic fibers is capable of distinguishing class I (healthy) from all other six plaque types (initial lesions, fatty streak, atheroma, fibrous atheroma, complex lesions, and calcific atheroma), as shown in Fig. 5, B and C. However, it does not distinguish between initial lesions (class II) and more advanced types such as atheroma and fibrous atheroma (class III). FD scores are significantly distinct when assessing classes II and IV for both collagen and elastin, and only features from elastin are different when comparing the most severe plaque types (classes III and IV).

Fig. 5.

A: American College of Cardiology-American Heart Association definition for atherosclerotic lesions, defining lesion categories based on their histological features. White, 2-photon emission fluorescence (TPEF; elastin); blue, second-harmonic generation (SHG; collagen). L, lumen. Scale bars, 25 μm. B and C: fractal dimension [arbitrary units (a.u.)] of TPEF (elastin) images (B) and (SHG; collagen) images (C). D and E: angular dispersion of elastic (D) and collagen (E) fibers, based on the directional analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. ns, Not significant. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test for nonparametric data was applied.

DA does not present significant fiber orientation differences between class I and class II as well as between classes III and IV, as shown in Fig. 5, D and E. However, all other classes can be successfully distinguished on the basis of the dispersion of the orientation of collagen and elastic fibers.

DISCUSSION

Physiologically, aging causes significant changes to the elastic properties of blood vessels (primarily arteries). The compliance of the aorta first rises during the growth and development phase to early adulthood and then falls in later life. After early adulthood, unfavorable changes occur. For example, atherosclerotic changes reduce vessel compliance because of progressive, diffuse fibrosis of the vessel walls due to increase in collagen remodeling (4, 19, 42). These changes were tracked by assessing the FD and direction of the elastic and collagen fibers.

The evaluation of arterial collagen and elastin changes by FD has been shown to be a successful strategy. Chow et al. (4) demonstrated that the fiber orientation distribution function from the fast Fourier transform analysis also shows remarkably different changes of the ECM structure in response to mechanical loading. In this study, we applied a similar approach based on FD analysis to obtain an objective measure of arterial ECM degradation and remodeling due to atherosclerosis progression and aging. Healthy and young animals present fibers that can be associated with fully developed and healthy IEL, which has not been affected significantly by atherosclerosis at the time of imaging. Middle-aged rabbits (animals aged 14–16 mo and 18–27 mo, respectively) show higher FD than what was observed in younger groups. This might be correlated with the progressing disruption of elastin protein structure as well as aggressive accumulation of collagen fibers, leading to diffuse thickening of intima.

One important observation is related to the images from newborn rabbits, as they present FDs almost as high as those obtained from imaging the oldest animals. Considering the significant age difference between these two groups of animals, such similarity could indicate the reversal of IEL structure back to pre-mature stages due to elastin structural breakdown, as previously modeled in other studies (8, 16, 17, 38).

TA and EIA have both shown lower FD. This observation can be explained by the fact that these regions experience less turbulent blood flow, even when plaque has started to develop (8, 38). As a result, these regions show fewer changes in the elastic layer and a lower amount of collagen deposition compared with the AA and AbA locations. From these results we can conclude that FD analysis can accurately track structural protein disruptions within the intima/IEL along the aorta.

FD analysis has been applied to estimate atherosclerotic plaque instability on ultrasound images, suggesting that FD could be useful as a single determinant for the discrimination of symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects (1). In this study, we explored the possibility of using FD to assess morphological ECM changes as a function of the aortic location, and therefore we were able to correlate these FD values with corresponding severity. During the course of atherosclerosis progression, certain locations along the aorta are more prone to plaque development than others (45). These locations include transition zones such as bends, arches, and bifurcations. At these locations the rate and pattern of blood flow are altered, thus affecting local hemodynamics (3, 46).

Attempts have been made to assess the role of hemodynamic factors in atherosclerosis by correlating the distribution of intimal lesions, usually in excised collapsed arteries, with presumed changes in blood flow conditions or with flow patterns visualized in idealized glass or plastic models. Elevations or variations in flow velocity and shear stress (3, 10), flow separation (35), and turbulence (5, 11, 41) have each been proposed as hemodynamic potentiating lesion formation. In this context, we have demonstrated that FD is a good indicator for assessing plaque burden in an eventual longitudinal study.

Comparing results in Fig. 3, C and D with location maps, it becomes clear that the locations with the highest FD values correspond to the AA and regions close to the two kidneys’ artery branches. These observations indeed support the assumptions of hemodynamic effects on atherosclerotic lesion formation as discussed above. In the AA, the pattern of blood flow is more complex than in the other regions along the descending abdominal aorta, with constant helical and extensive reversal flow resulting from the curvature of the arch and the strong pulsatility of flow (8, 16, 38). As a result, this turbulence of blood flow and change in arterial wall shear stress leads to elevated probability of plaque development within the vessel (8). Similarly, regions that are close to the kidneys’ artery branches also experience nonlaminar blood flow due to arterial bifurcation. This, too, significantly enhances the early development of atherosclerosis lesions (44).

Another interesting observation is that as the rabbit’s age increases, all four studied aorta regions (AA, TA, AbA, EIA) show increasing FD values, suggesting that the lesions are also advancing with age and are successfully tracked by FD.

In addition to the fractal analysis, the directionality of elastin and collagen fibers in TPEF and SHG images was also assessed. When more prominent horizontal structures appear in middle-aged rabbits, a delimiting of the fibers also begins to appear. Vertical small fibers can be found filling the spaces in between the horizontal main fibers. The distribution of these prominent fibers is detected and shown as one major peak in the corresponding histogram. One interesting observation is that older animals present segments with a flatter and more homogeneous directional distribution of both collagen and elastin compared with younger groups. This finding suggests that the process of fiber formation (young group) and fiber degradation (old group) presents some common characteristics, such as the lack of minor structures connecting the main fibers.

Finally, correlating the scores obtained by both FD and DA to distinguish between types of atherosclerotic lesions shows a promising value of using such analyses to classify lesions and/or disease severity. As the plaque burden becomes more complex, both scores can track the changes in most cases, despite the age of the animals and the location of such lesions. FD is more sensitive to changes disrupting the healthy arrangement of collagen and elastic fibers, whereas DA is successful in tracking the dispersion of fiber direction between lesion types. A combination of both methods could represent a potential classification tool when dealing with a large image data set of fiberlike structures.

Despite the promising potential to track fiber remodeling, one possible limitation of the FD method is that different textures may exhibit the same range of FD. This may be due to combined differences in coarseness and directionality, i.e., dominant orientation and degree of anisotropy. Although FD analysis did show favorable results for the specific case in this study, we advise that for image classification purposes a combination of methods (e.g., texture analysis, directionality, etc.) can be helpful to achieve better accuracy in evaluating fiber disruption imaged with TPEF and SHG. Also, although sectioned arterial tissue has been used in several studies aiming to track changes related to pathological and other conditions, one must be aware that sectioning might affect the IEL structure.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the feasibility of extracting quantitative features from TPEF and SHG images specifically tailored to track changes associated with elastin and collagen morphology. Although our study is only a proof of concept, we demonstrated a straightforward and computationally viable strategy to analyze fiber-related morphological information from optical images obtained from pathological tissue samples. Nonsubjective scores of TPEF and SHG images can have practical clinical significance in distinguishing pathologies involving fiberlike structures, but when applying these methods to in vitro studies researchers must be aware of potential limitations imposed by sample preparation such as sectioning, as it might affect the morphological structure of the tissue.

GRANTS

This work is partially supported by National Research Council Canada Genomics and Health initiative, and a Natural Science and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant in the form of student financial support.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.H., M.G.S., A.M., and A.C.-T.K. conceived and designed research; L.B.M.-G., M.S.D.S., B.S., and A.C.-T.K. performed experiments; L.B.M.-G. analyzed data; L.B.M.-G., M.G.S., and A.C.-T.K. interpreted results of experiments; L.B.M.-G. prepared figures; L.B.M.-G. drafted manuscript; L.B.M.-G., M.S.D.S., M.H., B.S., M.G.S., and A.C.-T.K. edited and revised manuscript; L.B.M.-G., M.S.D.S., M.H., B.S., M.G.S., A.M., and A.C.-T.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of M. G. Sowa: Kent Imaging, 804B 16 Avenue SW, Calgary, AB, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asvestas P, Golemati S, Matsopoulos GK, Nikita KS, Nicolaides AN. Fractal dimension estimation of carotid atherosclerotic plaques from B-mode ultrasound: a pilot study. Ultrasound Med Biol 28: 1129–1136, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(02)00550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellini C, Ferruzzi J, Roccabianca S, Di Martino ES, Humphrey JD. A microstructurally motivated model of arterial wall mechanics with mechanobiological implications. Ann Biomed Eng 42: 488–502, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caro CG. Discovery of the role of wall shear in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 158–161, 2009. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow MJ, Turcotte R, Lin CP, Zhang Y. Arterial extracellular matrix: a mechanobiological study of the contributions and interactions of elastin and collagen. Biophys J 106: 2684–2692, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowe WJ Jr, Krovetz LJ. Studies of arterial branching in models using flow birefringence. Med Biol Eng 10: 415–426, 1972. doi: 10.1007/BF02474222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doras C, Taupier G, Barsella A, Mager L, Boeglin A, Bulou H, Bousquet P, Dorkenoo KD. Polarization state studies in second harmonic generation signals to trace atherosclerosis lesions. Opt Express 19: 15062–15068, 2011. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.015062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans CL, Xie XS. Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy: chemical imaging for biology and medicine. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto, Calif) 1: 883–909, 2008. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frangos SG, Gahtan V, Sumpio B. Localization of atherosclerosis: role of hemodynamics. Arch Surg 134: 1142–1149, 1999. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frauenfelder T, Boutsianis E, Schertler T, Husmann L, Leschka S, Poulikakos D, Marincek B, Alkadhi H. In-vivo flow simulation in coronary arteries based on computed tomography datasets: feasibility and initial results. Eur Radiol 17: 1291–1300, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gimbrone MA Jr, Topper JN, Nagel T, Anderson KR, Garcia-Cardeña G. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 902: 230–240, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutstein WH, Schneck DJ, Marks JO. In vitro studies of local blood flow disturbance in a region of separation. J Atheroscler Res 8: 381–388, 1968. doi: 10.1016/S0368-1319(68)80095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kita T, Brown MS, Watanabe Y, Goldstein JL. Deficiency of low density lipoprotein receptors in liver and adrenal gland of the WHHL rabbit, an animal model of familial hypercholesterolemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78: 2268–2272, 1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko AC, Ridsdale A, Mostaço-Guidolin LB, Major A, Stolow A, Sowa MG. Nonlinear optical microscopy in decoding arterial diseases. Biophys Rev 4: 323–334, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s12551-012-0077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko AC, Ridsdale A, Smith MS, Mostaço-Guidolin LB, Hewko MD, Pegoraro AF, Kohlenberg EK, Schattka B, Shiomi M, Stolow A, Sowa MG. Multimodal nonlinear optical imaging of atherosclerotic plaque development in myocardial infarction-prone rabbits. J Biomed Opt 15: 020501, 2010. doi: 10.1117/1.3353960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ku DN. Blood flow in arteries. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 29: 399–434, 1997. doi: 10.1146/annurev.fluid.29.1.399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ku DN, Giddens DP, Zarins CK, Glagov S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low oscillating shear stress. Arteriosclerosis 5: 293–302, 1985. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.5.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le TT, Langohr IM, Locker MJ, Sturek M, Cheng JX. Label-free molecular imaging of atherosclerotic lesions using multimodal nonlinear optical microscopy. J Biomed Opt 12: 054007, 2007. doi: 10.1117/1.2795437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li ZY, Howarth SP, Tang T, Gillard JH. How critical is fibrous cap thickness to carotid plaque stability? A flow-plaque interaction model. Stroke 37: 1195–1199, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217331.61083.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lilledahl MB, Haugen OA, de Lange Davies C, Svaasand LO. Characterization of vulnerable plaques by multiphoton microscopy. J Biomed Opt 12: 044005, 2007. doi: 10.1117/1.2772652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lilledahl MB, Pierce DM, Ricken T, Holzapfel GA, Davies CD. Structural analysis of articular cartilage using multiphoton microscopy: input for biomechanical modeling. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 30: 1635–1648, 2011. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2139222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu ZQ. Scale space approach to directional analysis of images. Appl Opt 30: 1369–1373, 1991. doi: 10.1364/AO.30.001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig M, von Petzinger-Kruthoff A, von Buquoy M, Stumpe KO. [Intima media thickness of the carotid arteries: early pointer to arteriosclerosis and therapeutic endpoint]. Ultraschall Med 24: 162–174, 2003. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Lemus LA, Hill MA, Meininger GA. The plastic nature of the vascular wall: a continuum of remodeling events contributing to control of arteriolar diameter and structure. Physiology (Bethesda) 24: 45–57, 2009. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Megens RT, Reitsma S, Schiffers PH, Hilgers RH, De Mey JG, Slaaf DW, oude Egbrink MG, van Zandvoort MA. Two-photon microscopy of vital murine elastic and muscular arteries. Combined structural and functional imaging with subcellular resolution. J Vasc Res 44: 87–98, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000098259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertz J. Nonlinear microscopy: new techniques and applications. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 610–616, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mostaço-Guidolin LB, Sowa MG, Ridsdale A, Pegoraro AF, Smith MS, Hewko MD, Kohlenberg EK, Schattka B, Shiomi M, Stolow A, Ko AC. Differentiating atherosclerotic plaque burden in arterial tissues using femtosecond CARS-based multimodal nonlinear optical imaging. Biomed Opt Express 1: 59–73, 2010. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napolitano A, Ungania S, Cannat V. Fractal dimension estimation methods for biomedical images. In: MATLAB—A Fundamental Tool for Scientific Computing and Engineering Applications, edited by Katsikis V. London: InTech, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Rourke M. Arterial stiffness, systolic blood pressure, and logical treatment of arterial hypertension. Hypertension 15: 339–347, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.15.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfeffer CP, Olsen BR, Ganikhanov F, Légaré F. Multimodal nonlinear optical imaging of collagen arrays. J Struct Biol 164: 140–145, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sacks MS. Incorporation of experimentally-derived fiber orientation into a structural constitutive model for planar collagenous tissues. J Biomech Eng 125: 280–287, 2003. doi: 10.1115/1.1544508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sako Y, Sekihata A, Yanagisawa Y, Yamamoto M, Shimada Y, Ozaki K, Kusumi A. Comparison of two-photon excitation laser scanning microscopy with UV-confocal laser scanning microscopy in three-dimensional calcium imaging using the fluorescence indicator Indo-1. J Microsc 185: 9–20, 1997. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1997.1480707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Nakajima S, Shiraga N, Atsumi H, Yoshida S, Koller T, Gerig G, Kikinis R. Three-dimensional multi-scale line filter for segmentation and visualization of curvilinear structures in medical images. Med Image Anal 2: 143–168, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S1361-8415(98)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scharfstein H, Gutstein WH, Lewis L. Changes of boundary layer flow in model systems: implications for initiation of endothelial injury. Circ Res 13: 580–584, 1963. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.13.6.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schriefl AJ, Zeindlinger G, Pierce DM, Regitnig P, Holzapfel GA. Determination of the layer-specific distributed collagen fibre orientations in human thoracic and abdominal aortas and common iliac arteries. J R Soc Interface 9: 1275–1286, 2012. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Sezgin M, Sankur B. Survey over image thresholding techniques and quantitative performance evaluation. J Electron Imaging 13: 146, 2004. doi: 10.1117/1.1631315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahcheraghi N, Dwyer HA, Cheer AY, Barakat AI, Rutaganira T. Unsteady and three-dimensional simulation of blood flow in the human aortic arch. J Biomech Eng 124: 378–387, 2002. doi: 10.1115/1.1487357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiomi M, Ito T, Yamada S, Kawashima S, Fan J. Development of an animal model for spontaneous myocardial infarction (WHHLMI rabbit). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1239–1244, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000075947.28567.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starukhin P, Ulyanov S, Galanzha E, Tuchin V. Blood-flow measurements with a small number of scattering events. Appl Opt 39: 2823–2830, 2000. doi: 10.1364/AO.39.002823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stehbens WE. Turbulence of blood flow. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 44: 110–117, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strupler M, Hernest M, Fligny C, Martin JL, Tharaux PL, Schanne-Klein MC. Second harmonic microscopy to quantify renal interstitial fibrosis and arterial remodeling. J Biomed Opt 13: 054041, 2008. doi: 10.1117/1.2981830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun W, Chang S, Tai DC, Tan N, Xiao G, Tang H, Yu H. Nonlinear optical microscopy: use of second harmonic generation and two-photon microscopy for automated quantitative liver fibrosis studies. J Biomed Opt 13: 064010, 2008. doi: 10.1117/1.3041159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarbell JM. Mass transport in arteries and the localization of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 5: 79–118, 2003. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.040202.121529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Tullio MR, Russo C, Jin Z, Sacco RL, Mohr JP, Homma S; Patent Foramen Ovale in Cryptogenic Stroke Study Investigators . Aortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and death. Circulation 119: 2376–2382, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.811935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent PE, Plata AM, Hunt AA, Weinberg PD, Sherwin SJ. Blood flow in the rabbit aortic arch and descending thoracic aorta. J R Soc Interface 8: 1708–1719, 2011. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang HW, Le TT, Cheng JX. Label-free imaging of arterial cells and extracellular matrix using a multimodal CARS microscope. Opt Commun 281: 1813–1822, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.optcom.2007.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47a.Yen JC, Chang FJ, Chang S. A new criterion for automatic multilevel thresholding. IEEE Trans Image Process 4: 370–378, 1995. doi: 10.1109/83.366472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamir M. Fractal dimensions and multifractility in vascular branching. J Theor Biol 212: 183–190, 2001. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Webb WW. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat Biotechnol 21: 1369–1377, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nbt899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zoumi A, Lu X, Kassab GS, Tromberg BJ. Imaging coronary artery microstructure using second-harmonic and two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J 87: 2778–2786, 2004. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]