Abstract

Medicinal plant products have been used in health care since time immemorial. During the past three decades, the use of herbal supplements has been on the rise in the USA. A number of these products have been shown to possess the potential to interfere with blood clotting. This paper is a review of blood-thinning herbal supplements commonly used in the USA, accompanied by discussion of the dental implications of their use along with suggestions for prediction and prevention of the risk of bleeding. Twenty herbal supplements belonging to four pharmacological groups are identified and reviewed. While the majority (45%) of the supplements reviewed possesses antiplatelet properties, the remaining are dispersed among anticoagulant (15%), a combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant (15%), and other diverse groups (25%). The literature reveals that most of the available information on blood-thinning herbs is based on in vitro experiments, animal studies, and individual clinical case reports. Some herbal effects are also speculated based on theoretical grounds. These observations, together with the deficiency of the law regulating herbal supplements, indicate limitations of the literature and the regulatory mechanisms related to these products, further implying the need for additional research and improved regulation. While emphasizing the dental implications of the findings reported in the literature, suggestions were made for prediction and prevention of the risk of bleeding caused by herbal medications, based on the concepts of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine.

Keywords: Predictive preventive personalized medicine, Vascular injury, Risk factors, Bleeding, Blood-thinning, Coagulation pathways, Herbal supplements, Aloe, Ginger, Ginkgo, Garlic, Green tea, Grapefruit, Ginseng, Oregano, Dentistry, Obesity, Inflammation, Diabetes, Cancer, Infections, Individualized patient profile

Introduction

Herbal medications come from various types of plant sources that are used for prevention and/or treatment of diseases and other medical conditions. Records show that natural plant products have been employed throughout human history for therapeutic purposes, in most cases as a major form of therapy for millions of people worldwide. In many parts of the world, medicinal plant substances are recognized as herbal supplements and/or traditional medicines. However, products made from plant derivatives as purified chemical ingredients and subjected to scrutiny by official regulatory mechanisms are not considered as either herbal supplements or traditional medicines [1].

It is documented that more than 30% of the FDA-approved drugs currently in use were derived from plant sources and some of the commonly used drugs include aspirin, atropine, pilocarpine, morphine, lidocaine, quinidine, capsaicin, paclitaxel, reserpine, tubocurarine, and vincristine [1]. Besides being the origin of useful drug compounds, many other plant-based medicinal products are also known to be widely used, without official recognition or the need for prescriptions. Some of these natural products are supported scientifically for therapeutic usefulness, with the potential to be developed as drugs. Examples of such products include plant-based functional foods with anticancer properties [2], crude plant ingredients with the potential to prevent cardiovascular diseases [3], herbal preparations demonstrating effectiveness against neurological disorders [4], and plants and mushrooms having antiobesogenic and antidiabetic activities [5]. Despite these beneficial aspects, however, medicinal plant recipes are also associated with a number of adverse effects which can be of intrinsic or extrinsic origin [1].

The main objective of this review paper is to identify and review the commonly used herbal supplements in the USA that have the potential to interfere with blood clotting under dental settings. The dental implications of the use of these natural products are discussed along with recommendations for predictive and preventive measures to avoid/minimize the risk of bleeding. These herbal supplements were selected based on recent market-survey data and published information on utilization of supplements by US consumers [6–10].

Herbal supplements in the USA are manufactured products made from different parts of plants that are claimed to have medicinal properties [1, 9, 11]. These products are highly concentrated and have greater biological effects relative to respective raw material sources. Herbal supplements in the USA are a component of what are collectively known as dietary supplements within the realm of complementary and alternative medicine [1, 9, 11]. As such, the products are intended to be taken orally and can be obtained by consumers without prescriptions. As defined by the US Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), herbal supplements are not classified as drugs, nor are they intended for use as food. Therefore, these products are used without being regulated with the same scrutiny as conventional drugs, although they may be subjected to certain limited regulatory measures. Herbal supplements are thus marketed in USA largely with no proven assurance for safety and efficacy, the burden of proof for safety lying on the regulatory authority [1, 9, 11].

A number of recent surveys have shown that the use of herbal supplements in the USA has markedly increased in the past three decades, despite the noted regulatory limitations. For instance, national telephone surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics revealed that 2.2% adult Americans in the general population used these products in 1990 [12], while 18.8% used in 2002 [13]. Furthermore, a 2015 publication based on a nationwide survey reported that approximately 35% adult Americans use herbal supplements mostly on regular basis [14]. Depending upon specific circumstances, even greater utilization of these products has been observed among the elderly and medically compromised individuals [15–18]. Consistent with these reports, sales of herbal supplements in the US rose to $7.5 billion in 2016, with the market growing at about 8% per year [10].

In view of the growing use of herbs in the USA, it is likely that health care practitioners, including dentists, would see an increasing number of patients who take these products. It has been documented that as many as 70% of patients who take herbal supplements are unaware of their potential adverse effects and do not inform their health care providers about the use of these products [19]. Although the supplements are used with expectation of health benefits, with no proven effectiveness and safety, it has become increasingly clear that at least a portion the products cause adverse effects that may outweigh the benefits [1, 20]. As with most conventional drugs, the adverse effects of herbs may not only be limited to minor and predictable problems, but may also include effects that are more serious, uncommon, and unpredictable. These effects have been shown to be related partly to the way the products are manufactured and regulated, and to the lack of sufficient awareness on the part of many patients and even health care givers about the health issues associated with the products [1, 9, 20].

Information for the present review was collected from peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and other relevant resources. Besides using hard copy materials as sources of information, PubMed/Medline and Google searches were extensively made to access computer-generated information using the following specific search terms: herbal supplements, herbal medicines, herb–drug interactions, antiplatelet herbs, anticoagulant herbs, fibrinolytic herbs, oral health, dental effects, bleeding, blood clotting, adverse effects of herbs, toxicity of herbs, and herbal interaction with conventional drugs.

Basic mechanisms of blood clotting relevant to herbal supplement use

Under normal physiological conditions, moderate levels of small blood vessel injuries and bleeding, accompanied by reparative responses, occur routinely [21]. However, in certain severe situations, abnormalities in hemostasis can occur, resulting in excessive bleeding (hemorrhage) or blood clot (thrombus formation). The basic mechanisms of blood clot formation following injury/bleeding, and the attendant repair processes are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2 [21, 22].

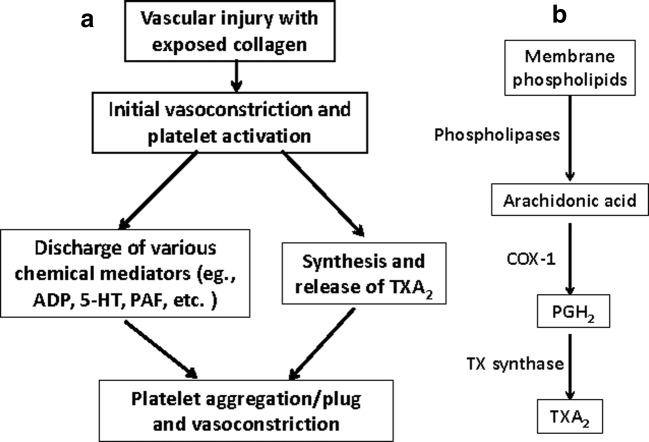

Fig. 1.

Sequences leading to (a) formation of platelet plug and vasoconstriction, and (b) synthesis of TXA2 (TXA2, thromboxane A2; COX-1, cyclooxygenase-1; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; TX, thromboxane; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; PAF, platelet activating factor; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine)

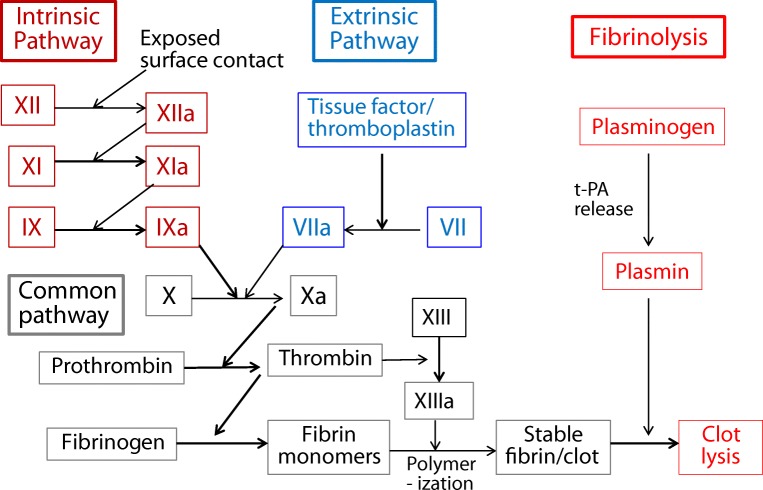

Fig. 2.

Blood clotting (coagulation) cascade and clot resolution (fibrinolysis) (t-PA, tissue plasminogen activator)

Vascular injury and bleeding initiate a series of reactions that stop bleeding and maintain a normal balance within the system. These reactions include vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, blood coagulation (clot formation), and clot resolution [21, 22]. Although the initial vasoconstriction that follows blood vessel injury contributes to a reduction of bleeding, the cessation of bleeding ultimately depends on the formation of platelet plug and blood coagulation. The creation of platelet plug involves initial adhesion and activation of platelets at the site of injury, followed by further activation and aggregation of platelet by released chemical mediators, such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP), platelet activating factor (PAF), serotonin, and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (Fig. 1a) [21–23]. The platelet plug thus formed serves as a temporary/primary hemostatic plug [21–23]. As shown in Fig. 1b, TXA2 is formed from membrane phospholipids via arachidonic acid pathways involving various enzymes including cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) [21–23]. This component of the initial hemostatic process is a major target for the actions of many blood-thinning substances, including herbal supplements.

The process of blood coagulation (clotting) begins with two different and independent pathways, intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, which converge to the same point (a common pathway) after some steps (Fig. 2) [22]. This process takes place at the site of vascular injury with the involvement of intravascular (within blood) and extravascular (from tissue) elements, platelets, and active proteases (active factors). After convergence, both pathways end up with the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin. Thrombin, as an active protease, converts fibrinogen to fibrins, which polymerize to insoluble strands of meshwork. In combination with blood cells, the fibrin meshwork finally forms a more stable clot (thrombus) [21, 22], which provides secondary hemostasis.

Coagulation is regulated by different mechanisms to maintain homeostasis. While the process of fibrinolysis removes excessive clots, other regulatory mechanisms prevent coagulation in uninjured blood vessels, by producing prostacyclin (PGI2), nitric oxide (NO), thrombomodulin, protein C, tissue factor, antithrombin III, and heparin, among others [21, 22]. Vitamin K, on the other hand, counteracts the tendency for bleeding. Overall, coagulation, anticoagulation, and fibrinolysis together provide the means to maintain a delicate balance in the blood, and the regulation of this complex process indicates multiple potential molecular targets of interference [21–23].

Many herbal products are reported to possess antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant properties, having the potential to impair hemostasis and cause/promote bleeding. Other herbals are also known to affect hemostasis by other mechanisms. The intensity of the effects of the different herbal medicines on hemostasis may vary depending on a number of factors, including the type and dose of the herbs used, the susceptibility of the patient, the severity of blood vessel damage, and the presence of interacting substances. The following is a discussion of the commonly used herbal supplements in USA, with potential consequences on blood clotting.

Common herbal supplements with the potential to interfere with blood clotting

Herbs with antiplatelet properties

Review of the literature indicates that the majority of herbal supplements that potentially interfere with blood clotting produce their effects through inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation [6, 20, 23–25]. It has been reported that these antiplatelet effects are mediated by mechanisms involving inhibition of formation, release, and/or actions of platelet-activating/aggregating endogenous mediators by constituent compounds present in the different herbal products reviewed, as depicted in Fig. 1. The commonly used herbal supplements in the USA with reported antiplatelet properties are discussed below.

Aloe

Aloe (Aloe vera) has been widely used as a medicinal plant for centuries. It is well known for its use in the treatment constipation and related gastrointestinal disorders [26, 27]. Other, but less common, uses of the herb include treatment of obesity, inflammation, diabetes, cancer, and infections [20]. Various constituents of the herb are believed to be responsible for its claimed therapeutic benefits. Of greater relevance among the different identified compounds are found anthraquinone glycosides, aloinosides, chrysophanic acid, and salicylates [26–29]. As an herbal supplement, aloe is available in the forms of soft gels and capsules. Besides its effects related to the above conditions, the supplement has also been reported to possess antiplatelet activity, which is linked to at least its salicylate components [26, 27]. Consistent with this, in one case scenario, a woman on aloe supplement was diagnosed suffering from excessive bleeding after oral surgery [30]. In this scenario, aloe was also found to interact with the general anesthetic, sevoflurane, and cause abnormal bleeding during surgery [30]. Based on these preliminary findings, it was recommended that aloe supplement should be avoided from being used at least for 2 weeks before surgery [6, 20, 24]. Another cause for concern is its potential to increase bleeding if antiplatelet analgesic drugs, such as aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are used simultaneously; these drugs are commonly used in dental practice.

Cranberry

Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) is claimed to be used for prevention and treatment of urinary tract infection, anorexia, diabetes, stomach ailments, and blood disorders, among several other effects [26, 27]. Cranberry supplements are available as concentrated liquid extracts, tablets, and capsules. The herb is a rich source of certain types of phytochemicals, including flavonoids, glycosides, anthocyanins, and triterpenoids [26, 27]. It has also been reported to contain salicylic acid, which has resemblance to aspirin. There are also indications that some of the major medicinal properties of cranberry come from its anthocyanin component. With regard to effects on blood clotting, it is expected that salicylic acid has the potential to cause inhibition of platelet aggregation [8, 26]. There are case reports of interactions between the herb and warfarin, demonstrating increased international normalized ratio (INR) and bleeding when both are used concomitantly [8, 20]. Although cranberry has not been verified to directly affect platelet aggregation or interact with antiplatelet drugs, the possibility cannot be ruled out under certain favorable circumstances. It is, therefore, advisable to be cautious when the herb is used together with antiplatelet drugs, such as aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly in excessive doses.

Feverfew

In addition to its overall popularity in the USA, feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) ranked among the top 15 herbal supplements out of 21 used by adult dental patients we studied previously [7]. It has been mainly used for treating migraine headaches, arthritis, gastrointestinal disorders, allergies, and fever [26, 27]. Feverfew supplement is available as tables, capsules, and liquid extracts/tinctures. The sesquiterpene lactone, parthenolide, has been reported to be responsible for most of the effect of the herb [20, 26, 27]. This compound blocks the synthesis and/or release of various chemical mediators, such as prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, histamine, and serotonin, in platelets and some other cells. The mechanism for these effects of the herb involves inhibition of phospholipase A2 and arachidonic acid metabolism [20, 26, 27]. Consequently, feverfew has been shown to produce marked inhibition of platelet aggregation in vitro [20, 26, 27]. However, there appears to be no evidence for the effect of the herb on hemostasis or its interaction with blood-thinning drugs, such as NSAIDs. Nonetheless, considering the reported antiplatelet activity of feverfew, caution should be used in patients who use the herb excessively or with medications that inhibit platelet aggregation.

Garlic

Garlic (Allium sativum) has been reported to be one of the top selling herbs in the USA. In our previous survey, it was among the top ten herbal supplements used by adult dental patients [27]. Its popularly as a dietary supplement is based on the belief that it provides several cardiovascular benefits to regular users, which include lowering of elevated blood pressure, prevention of age-related cardiovascular disorders, and reduction of serum lipids and body weight control, among others [26, 27, 31]. Garlic supplements are marketed as tablets and capsules filled with garlic oil. Garlic preparations manufactured under different conditions may contain different bioactive compounds, which include alliin/allicin (and its degradation products), ajoens, and several other sulfur-containing essential oils. Most ingredients of garlic, particularly alliin, have been demonstrated to inhibit the production and/or release of chemical mediators, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF), adenosine, ADP, and thromboxanes [20, 24]. Some of the compounds also act as antioxidants and cause reduction of mobilization of intracellular calcium [32]. The mechanisms for the above effects have been suggested to include inhibition/blockade of COX and fibrinogen receptors on platelet membranes by some garlic compounds. Overall, these effects are implicated to be associated with inhibition of platelet aggregation and enhancement of bleeding by different garlic preparations. In support of this contention, there are various reports based on human as well as animal studies. For instance, in one such study a reduction of platelet aggregation by garlic oil supplement was shown in healthy human adults [33]. In another study involving an elderly man, the development of a spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma and postoperative bleeding were observed after ingestion of a large dose of garlic product [34]. In a male patient who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate, hemorrhage was detected for a period of 4 h after surgery due to the use of garlic tablets [35]. The findings of two other studies have also implicated that garlic augments the antiplatelet and anticoagulant activities of aspirin/NSAIDs and other blood-thinning medications, particularly warfarin in association with increased risk of bleeding [20, 26, 27]. From the above, it is prudent that patients and practitioners should be well aware of the concerns raised in relation to the use of garlic supplements.

Ginger

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) is widely used for its medicinal properties to alleviate/prevent nausea, vomiting, anorexia, cardiovascular conditions, bronchitis, arthritis, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and more [20, 26, 27, 36]. As a supplement, ginger is available in the forms of liquid extracts/oil, tablets, capsules and tea bags. The volatile oil of ginger is composed of zingiberene, bisabolene, shogaol, and gingerols [20, 24, 26, 27], which all have been reported to inhibit platelet aggregation through inhibition of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis [37]. Consistent with this, it was shown in one study that a relatively high dose of ginger inhibited platelet aggregation in patients with coronary artery disease [38]. However, no studies have so far demonstrated a significant effect of ginger’s constituents on blood clotting in humans with any blood-thinning medications of direct dental relevance. Based on one case report, nonetheless, ginger has been shown to increase bleeding in patients on warfarin [8]. These observations suggest the need for further research on this subject area. As the severity of adverse effects of herbal supplements as well as drugs may depend upon various factors, such as the doses and type of drugs used and susceptibility of the user, caution should, however, be exercised when using any substances suspected of such effects, including ginger preparations.

Ginkgo

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) is one of the most popular herbal supplements in the USA. We also found in our previous study that it was one of the top ten herbal products used by a sector of US dental patients [7]. Ginkgo leaf extracts as liquids are commonly used supplements for treating various conditions associated with cerebral and peripheral circulatory disorders and ischemia, such as dementia, impotency, tinnitus, vertigo, and intermittent claudication. Other formulations include capsules and tables. Supplements of ginkgo contain a number of bioactive compounds and these include the flavone glycosides, kaempferol and quercetin, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes (ginkgolides A, B, C, and M) [32, 39–41]. Of the different constituents, ginkgolides, particularly ginkgolide B, have also been shown to inhibit the aggregation of platelets in vitro by inhibiting PAF formation and binding to its receptors on platelet membranes. Corroborating with this, one study found significant inhibition of platelet aggregation in human volunteers after using ginkgolides [32, 41, 42]. In another study, enhanced bleeding has been reported in patients treated with either ginkgo alone or in combination with NSAIDs, the latter causing greater enhancement. Similarly, a case report described spontaneous bleeding in the eyes of an adult male who was given aspirin while taking ginkgo extracts [43]. Briefly, these observations suggest that ginkgo has the potential to cause or promote bleeding and the concurrent administration of aspirin or other NSAIDs may present an additional risk. Appropriate precautionary measures are in order to avoid or minimized such adverse effects in patients on ginkgo, especially if intraoperative or postoperative bleeding is a concern or other platelet inhibitors are sought to be used [6, 20, 24].

Meadowsweet

Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) is frequently used for conditions like cough, muscle aches, headaches, fever, cold, rheumatism, gout, kidney disease, digestive disorder, menstrual cramps, and cardiac problem [20, 26, 27]. It is available as liquid preparation and capsule. It contains different compounds, but salicylate and phenolic glycosides are major contributors to its medicinal properties [25, 26, 44]. Due to the presence of salicylates, the use of meadowsweet is associated with antiplatelet effects. However, there are no reports of interactions between meadowsweet and NSAIDs or any other blood thinners, and concerns regarding the simultaneous use of NSAIDs and this herbal supplement remain theoretical. Although no health problems are reported in conjunction with the use of meadowsweet at recommended doses, it is advisable to be suspicious of possible adverse effects that might occur in case of unusual circumstances.

Turmeric

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is claimed to be used for various medical reasons including treatment of indigestion, loss of appetite, inflammation, pain, arthritis, skin infections, and various forms of cancer [22, 23, 45]. Turmeric products available as herbal supplements are in the forms of capsules, tablets, and liquid extracts prepared from the roots of the herb. Turmeric contains the volatile oils zingiberene and turmerone, and curcumin. The volatile oils have antispasmodic and antibacterial actions, while curcumin produces anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet effects [20, 24, 26]. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that the antiplatelet effect of curcumin/turmeric is due to inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism and TXA2 synthesis [20, 26, 27, 46]. However, there are no reports regarding the effect of the compound on blood clotting/bleeding. Similarly, there are neither experimental nor clinical data indicating interactions between turmeric and antiplatelet drugs, such as aspirin and other NSAIDs. The risk for abnormal bleeding cannot, however, be ruled out with the use of turmeric, especially in the presence of blood-thinning drugs under certain circumstances, such as increased susceptibility of consumers and the use of large doses. Assuming these possibilities, caution needs to be applied when curcumin or turmeric is used either alone or in combination with antiplatelet medications.

White willow

White willow (Salix species) is also known by several other names, such as black willow, European willow, salicin willow, or withy [26]. It has been claimed to be used for relieving inflammation, pain, rheumatism, fever, and flu. The supplement comes as capsules and liquid extracts. The active principles of white willow include salicylic acid, salicin, salicortin, and their derivatives, which are closely related to aspirin [20, 26, 27, 39, 40]. Therefore, it is not unexpected that the herb induces similar pharmacological effects as aspirin, including antiplatelet activity. However, there are no documented reports about white willow causing increased bleeding or interacting with NSAIDs or other blood-thinning drugs [20]. Nonetheless, due to its aspirin-like antiplatelet constituents, caution should be exercised when using this herbal supplement, particularly in combination with other antiplatelets, including NSAIDs, in order to avoid or minimize the risk of bleeding. On the other hand, results of one study have suggested that salicylate decreases serum levels of the analgesic drug naproxen, while increasing its clearance, but the effect of this interaction on hemostasis remains to be determined [47].

Herbs with anticoagulant properties

Herbal supplements reported to have anticoagulant activities have been shown to contain coumarins, together with other constituents. Coumarins exist as natural as well as synthetic compounds, and the widely used prescription anticoagulant, warfarin, is a synthetic derivative. These compounds are blockers of the action of vitamin K, and, as such, interfere with the synthesis of clotting factors and clot formation (Fig. 2). Below are described the commonly used herbal supplements with reported anticoagulant activities.

Chamomile

Chamomile (Matricaria recutita, Chamaemelum nobile) is commonly used for its claimed benefits as an antispasmodic and a sedative [20, 26, 27]. Being classified as a dietary supplement, it is marketed in the forms of capsules, fluid extracts, and tea bags. Chamomile consists of multiple compounds, including coumarins, heniarin, flavonoids, farnesol, nerolidol, germacranolide, and various glycosides [20, 26, 27]. Despite the presence of coumarins, the effect of chamomile per se on the coagulation process has not been investigated. However, an isolated case of enhanced bleeding in a patient taking warfarin with chamomile has not been reported [48]. Thus, the effect of the herb alone on hemostasis (acting as anticoagulant or antiplatelet) is not clear. However, until more definite information is available, it is advisable to be vigilant of its potential effect on blood clotting.

Fenugreek

Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) is often used for diabetes mellitus, gout, inflammation, gastrointestinal problems, and muscle pain [20, 26, 27]. As an herbal supplement, it is available in the forms of concentrated liquid extracts and capsules. Bioactive constituents of fenugreek seeds include various saponins, alkaloids, and coumarins [20, 26, 27], but there are no reports that indicate that fenugreek or its coumarin constituent has effects on blood clotting when used with or without other drugs. However, the possibility of enhanced bleeding cannot be ruled out, particularly under certain circumstances, such as use of high doses in susceptible users.

Red clover

Red clover (Trifolium pratense) is one of the top 15 herbal supplements we previously reported to be used by adult dental patients [7]. It has been widely claimed to alleviate the symptoms of menopause and to treat skin conditions and respiratory problems, among other conditions [26, 27]. As a dietary supplement, tablets, capsules, tea bags, and liquid extracts of the herb are available. Red clover contains several volatile oils (e.g., benzyl alcohol, methyl salicylate, and methyl anthranilate), isoflavonoids, cyanogenic glycosides, and coumarins [26, 27]. Because of the presence of coumarins, red clover has been hypothesized to increase the risk of bleeding and potentiate the effects of other blood-thinners. This possibility remains to be supported with experimental and/or clinical data. Despite this uncertainty, however, it is advisable to be watchful when using this herbal supplement for any reason.

Herbs with both antiplatelet and anticoagulant properties

Some herbal products have been reported to possess both antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects, with the possibility of causing increased bleeding by both mechanisms (Figs. 1 and 2). Below are popular herbal supplements used in the USA that are reported to act by such pharmacological mechanisms.

Dong quai

Dong quai (Angelica sinensis) is originally a Chinese traditional medicine promoted in the USA as a dietary supplement for treating mainly gynecological complaints and migraine headache. It is also claimed to produce mild sedative, analgesic, antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, and antiplatelet/anticoagulant effects [20, 26, 27, 49]. Dong quai supplement is available as tablets, teas, and alcohol extracts. Constituents of don quai include several coumarin derivatives, such as oxypeucedan, osthole, psoralen and bergapten, and ferulic acid [20, 26, 27, 49]. Due to the different coumarins it contains, dong quai, as an anticoagulant, was found to prolong prothrombin time and worsen bleeding [48]. In addition, the ferulic acid component has been shown to possess antiplatelet activities both in vivo and in vitro. The antiplatelet effect is related to inhibition of release of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and ADP from platelets by ferulic acid [49–52]. Because of its effects on blood clotting, dong quai has been implicated in enhancement bleeding with warfarin [53], although, as yet, there are no reports demonstrating its interaction with NSAIDs and other types of blood thinners. However, patients who take the herb, particularly in large doses and/or in combination with blood-thinning medications, are advised to be more cautious.

Evening primrose

Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) is a popular herb, the seeds of which are used to produce oil (26). It is among the top 15 herbal supplements we showed previously as being used by a segment of US adult dental patients [7]. The oil of evening primrose is used internally as a supplement for a number of medicinal purposes, including treating rheumatic arthritis, osteoporosis, multiple sclerosis, Sojourn’s syndrome, cancer, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular conditions, inflammation, mental disorders, chronic fatigue, respiratory diseases, gastrointestinal disorders, premenopausal syndrome, and endometriosis, among others [26]. The oil product contains different fatty acids, including the unsaturated omega-6 fatty acid, gamma (γ)-linolenic acid (GLA). Gamma-linolenic acid is converted to prostaglandin E1 in vivo, which contributes, at least in part, to the claimed effects of the oil. Besides the above and some related effects, evening primrose oil has also been reported to reduce thromboxane production, platelet aggregation, and increased bleeding time (or slow clotting time) in hyperlipidemic male patients [26]. In animal studies using rabbits, it was also found that the seed oil of the herb has both antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects [54]. These findings suggest that evening primrose oil can enhance the chance of bleeding during or after surgery, and when taken together with medications that also increase bleeding or slow clotting, and such medications include the antiplatelets aspirin, NSAIDs, and naproxen, and the anticoagulants heparin and warfarin. It is therefore recommended that evening primrose supplement should not be taken along with blood-thinning medications, and its use should be stopped for a sufficient period of time before surgery.

Ginseng

Besides being one of the commonly used herbs in the USA, we found out that ginseng supplement was also one of the top ten products used by adult dental patients [7]. There are at least three varieties of ginseng on US herbal supplement market: American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng), and Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus) [26, 27]. As a dietary supplement, ginseng is frequently used to boost the immune system, stamina, physical capacity, mental performance, particularly in the elderly and individuals recovering from illness, and treatment of certain forms of cancer [55, 56]. Ginseng root preparations are available as capsules, tablets, tea, liquid extract, and candy [26]. A group of compounds known as ginsenosides are believed to be the bioactive components of the herb [55].

In relation to blood clotting, in vitro studies have shown that at least some components of ginseng inhibit TXA2 formation and platelet aggregation [26, 27, 55]. In addition, several case studies have provided evidence of increased bleeding in association with the use of ginseng [57]. Accordingly, in a 72-year-old woman, ingestion of ginseng tables was found to be linked to increased vaginal bleeding [58], while uterine bleeding was observed in a woman of 44 years of age after application of ginseng cream to her face [59]. However, the effect of ginseng on blood coagulation per se and the anticoagulant action of warfarin are not consistent. Although there are no reports of interactions between ginseng and drugs with antiplatelet activities, given the reported antiplatelet and anticoagulant (although inconsistent) properties of ginseng, caution should be taken when the supplement is used with such types of medications.

Herbs interfering with blood clotting by other mechanisms

From review of the literature, it was found that some other commonly used herbal supplements manifest blood-thinning activity by mechanisms which appear to be different from those described above for other herbal products. Presented below is review of these herbal supplements.

Flaxseed

Consistent with its widespread popularity, flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) is one of the top ten herbs used by adult dental patients that our group surveyed previously [7]. Used as a medicinal substance, flaxseed or its oil is usually taken as a laxative, and for the treatment of inflammation, cardiovascular disorders, metabolic syndrome, and cough/cold [26, 27]. Both the seeds and oil contain fatty acids, which are particularly rich in alpha (∝)-linolenic acid (ALA), an omega-3 fatty acid. The oil of flaxseed in capsules is more commonly used as a supplement. Based on theoretical grounds, ALA is believed to cause changes in the composition of platelet membrane, and this may be the reason for potentiation of the effects of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications by flaxseed or its oil [26]. However, this hypothesis awaits verification with experimental and/or clinical data. In the interim, caution needs to be exercised when using flaxseed oil supplement with these drugs.

Grapefruit

Grapefruit (Citrus paradisi) is a more recent addition to the list of herbs widely used in the USA as a dietary supplement [10]. It is claimed to be used more often for treating asthma, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, and infections of various types [27]. The supplement product is available as capsules and powder of concentrated extract. Grapefruit’s bioactive components include primarily furanocoumarins, which have been shown to inhibit CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 activities irreversibly [8]. As these enzymes are involved in the metabolism of warfarin, grapefruit products have been reported to interact with this anticoagulant drug at pharmacokinetic level. In one study, patients on warfarin for 3 days were observed to suffer from minor hematoma and increased INR after taking grapefruit supplement [8, 60] and this effect was subsequently shown experimentally to be linked to inhibition of the metabolism of warfarin by the supplement [8]. These findings provide evidence for health care providers and patients to be watchful of the potential harmful interactions between warfarin and grapefruit. The effect of grapefruit on other blood-thinning compounds (e.g., NSAIDs) has not been reported, but, unless proven otherwise, the possibility of such interactions with these drugs cannot be ruled out.

Green tea

Green tea (Camellia sinensis) is one of the most commonly consumed herbs in the USA [10]. As shown by our previous survey, it is also the most popular herbal supplement used by US adult dental patients [7]. As a dietary supplement, green tea is supplied as capsules, tablets, tea bags, and liquid extracts [26]. The herb is widely claimed to be used for improving mental efficiency and treating health conditions, such as depression, headache, inflammatory disorders, hyperlipidemia, obesity, some kinds of cancer, cardiovascular disorders, oral conditions, bone loss, and flu/cold, among several others [26, 27, 61, 62]. Caffeine and various types of polyphenols are considered to be the major bioactive substances contributing to the claimed beneficial effects of green tea. While caffeine works mainly as a stimulant, the polyphenols seem to be responsible for many of the other effects reported.

In relation to blood clotting, green tea has been reported to contain some vitamin K as well as antiplatelet polyphenols [7, 8, 26]. Due to the presence of vitamin K, it is implicated in counteracting the effects anticoagulant drugs, such as warfarin, under certain conditions. Supporting this assertion, in a 44-year-old man on warfarin, a relatively high dose of green tea was found to reduce the INR from 3.79 to 1.37 [63]. The antiplatelet polyphenols in green tea, particularly catechin, have been reported to reduce or stop blood clot formation as a result of inhibition of arachidonic acid formation and thus TXA2 generation in platelets [26, 27]. Although further work is needed to establish this finding, in the interim, it is advisable to be vigilant when patients on green tea supplement receive treatment with blood-thinning drugs (e.g., nonopioid analgesics) and/or undergo invasive procedures.

Oregano

Oregano (Origanum vulgare) is another recent addition to the list of herbs recognized as herbal supplements in the USA [10]. This supplement is widely claimed to be used for multiple illnesses like respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders, infections (microbial and parasitic), allergy, various types of cancer, and arthritis [26, 27]. In addition, more recently, oregano was reported to produce antihyperlipidemic and antidiabetic effects in animal experiments, and a distinct tumor-suppressive action in experimental models of breast cancer, with promising therapeutic potential [64]. As an herbal supplement, oregano is formulated as capsules and liquid preparation (oregano oil). Certain compounds identified in oregano have been proposed to be responsible for alleviating at least for some of the conditions described. These compounds include flavonoids (primarily naringin), and the essential oils, monoterpenoids, and monoterpenes (primarily carvacrol and thymol) [26].

From limited observations, oregano has been suggested have the potential to induce bleeding and exacerbate disorders of bleeding [65]. Accordingly, at high doses, it is expected to cause greater bleeding episodes, especially in individuals with bleeding disorders and in surgery involving significant vascular damages [65]. However, the mechanism for this effect of the herb has not been identified. In addition, no information is available on interactions between oregano and drugs interfering with blood clotting. Despite limited information, oregano users are generally advised to be cautious when taking blood-thinning medications and to stop taking the herb before surgery [65].

Saw palmetto

Aside from its overall popularity, saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) is among the top ten herbal supplements used by adult dental patients we reported previously [7]. It is used predominantly for treating benign prostate hyperplasia [26, 27]. It is available as an herbal supplement in the forms of capsules and oral liquid preparations. Saw palmetto contains a number of bioactive constituents, including steroids, flavonoids, and various fatty acids, and some of these compounds have been reported to inhibit COX and arachidonic acid metabolic products [26, 27]. However, the herb has not been observed to inhibit platelet aggregation in adult volunteers after 2 weeks of treatment. On the other hand, concomitant use of warfarin resulted in increased risk of bleeding, based on observation of a case involving a 53-year old-man who underwent surgical procedures to remove brain tumor after taking saw palmetto [66]. In the absence of coumarin compounds in saw palmetto and lack of demonstrable antiplatelet activity, the mechanism for the increased anticoagulant effect of warfarin by saw palmetto remains obscure. Despite this shortcoming, however, caution is advised if this herbal supplement is taken during surgical procedures and/or with blood-thinning medications, including NSAIDs.

The effects of the herbal supplements described above under different categories are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of reported effects of herbal supplements on blood clotting and their potential interactions with medications having blood-thinning properties relevant to dentistry [3, 16, 20–23, 27–31, 33–38, 41–45, 47, 49–53, 55]

| Herbal supplements | Effects on blood clotting and potential mechanisms | Potential interactions with anti- platelet/blood-thinning medications |

|---|---|---|

| Antiplatelets | ||

| Aloe | Certain chemical constituents, including salicylate, cause inhibition of platelet aggregation, and increased bleeding during/after surgery. | Enhanced bleeding with the general anesthetic, sevoflurane, during surgery; no report of interactions with antiplatelet and other blood-thinning medications. |

| Cranberry | Constituents include salicylic acid with potential antiplatelet activity, but this activity has not been verified, and there are no reports of the effect on hemostats. | Increased bleeding with warfarin, but no reports of interactions with medications having antiplatelet properties. |

| Feverfew | Certain components, especially parthenolide, inhibit platelet aggregation by inhibiting phospholipase A2 and arachidonic acid metabolism, but no reports of effects on blood clotting/bleeding. | No evidence of interactions with blood-thinning medications, including those with antiplatelet properties. |

| Garlic | Certain constituents inhibit platelet aggregation and induce bleeding under different conditions by inhibiting production/release of various mediators including TXA2, ADP, PAF, and adenosine. | Augments antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects of aspirin/NSAIDs and warfarin, respectively, with increased risk of bleeding. |

| Ginger | Certain constituents reduce platelet aggregation by inhibiting synthesis of TXA2, with the potential to increase bleeding. | Increased bleeding with warfarin, but no evidence of interactions with medications with antiplatelet properties. |

| Ginkgo | Certain components, particularly ginkgolides, inhibit platelet aggregation and cause bleeding by inhibiting PAF formation and binding to its receptors on platelet membranes. | Results in increased risk of bleeding with aspirin-like analgesics with antiplatelet effects |

| Meadowsweet | Constituents such as salicylate reported to produce antiplatelet activity by inhibiting effects of PAF, but no reports of alteration in blood clotting or hemostasis. | No reports of interactions with antiplatelet or other blood-thinning medications. |

| Turmeric | Certain components, especially curcumin, inhibit platelet aggregation by inhibiting arachidonic acid metabolism and TXA2 synthesis, but no evidence of causing bleeding. | No reports of interactions with antiplatelet or blood-thinning medications. |

| White willow | Certain salicylate-like components, reported to inhibit platelet aggregation, but no report of effects on blood clotting. | No reports of interactions with antiplatelet or blood-thinning medications. |

| Anticoagulants | ||

| Chamomile | Among multiple constituents, it contains coumarins, but has not been shown to affect blood clotting when used alone. | Causes increased bleeding in the presence of warfarin, but interactions with other blood thinners is unknown. |

| Fenugreek | Among multiple constituents, it contains coumarins, but has not been shown to affect blood clotting. | No reports of interactions with blood-thinning medications. |

| Red clover | Among multiple constituents, it contains coumarins, but has not been shown to affect blood clotting. | No reports of interactions with blood-thinning medications. |

| Antiplatelets and anticoagulants | ||

| Dong quai | Certain components, particularly coumarins and ferulic acid cause anticoagulant and antiplatelet effects, respectively; ferulic acid causes increased bleeding by inhibiting release of serotonin (5-HT) and ADP. | Increased risk of bleeding with warfarin, and potentially with other blood thinners, including aspirin and NSAIDs. |

| Evening primrose | Constituents contain fatty acids, including gamma (γ)-linolenic acid, believed to be associated with reduction of TXA2 and platelet aggregation, and increased bleeding time (slowing clotting). | Increased risk of bleeding or slowing clotting with blood-thinning medications, including aspirin, NSAIDs, and warfarin. |

| Ginseng | At least some constituents have antiplatelet effects with the risk of causing increased bleeding via inhibition of TXA2; reported to cause inconsistent anticoagulant effect. | No reports of interactions with antiplatelet medications, but inconsistent effects on anticoagulant action of warfarin, |

| Other herbal products | ||

| Flaxseed | Alpha (∝)-linolenic acid component hypothesized to alter platelet membrane composition with potential effect on hemostasis. | Potentiation of effects of medications with antiplatelet and anticoagulant properties. |

| Grapefruit | Furanocoumarin component reported to inhibit certain cytochrome P450 (CYP), but no reports of effect on blood clotting. | No reports of evidence of interactions with antiplatelet medications, but increases the anticoagulant effect of warfarin by inhibiting its metabolism. |

| Green tea | Certain components, particularly vitamin K and catechin, reported to have procoagulant and antiplatelet properties, respectively; antiplatelet effect reported to reduce/stop blood clots by inhibiting arachidonic acid metabolism and TXA2 formation. | No reports of evidence of direct interactions with antiplatelet medications, but counteracts blood-thinning effect of warfarin. |

| Oregano | Limited observations suggest certain constituents have the potential to induce bleeding and exacerbate bleeding disorders. | No reports of evidence of interactions with antiplatelet or blood-thinning medications. |

| Saw palmetto | Certain unidentified component(s) inhibits COX and arachidonic acid metabolism, but no impairment of platelet aggregation or alteration of hemostasis reported. | Increased risk of bleeding with warfarin, but no report of interactions with other blood-thinners. |

TXA2 thromboxane A2, ADP adenosine diphosphate, PAF platelet-activating factor, 5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine, CYP cytochrome, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, COX cyclooxygenase

Dental implications of the risk of bleeding caused by herbal medications, and predictive and preventive measures

The growing trend of herbal supplement use in the USA and the potential adverse effects associated with this make it increasingly relevant for health care providers, including dentists, and consumers as well to become more aware of the effects these products [1, 7]. Of the variable adverse effects caused by herbal supplements is found the risk of enhanced bleeding, which has considerable significance to the oral cavity and the practice of dentistry in a number of aspects.

The risk of bleeding caused by blood-thinning herbal supplements can be increased in dental patients under two major conditions: by invensive dental procedures and concomitant administration of blood-thinning drugs [7, 9, 24, 25].

Although the nature and magnitude of adverse effects of herbal supplements may vary depending upon intrinsic and extrinsic factors, supplements interfering with blood clotting have the potential to pose significant bleeding after major oral and maxillofacial surgery [2, 7, 9]. Bleeding caused by these products can also be a nuisance during minor surgical procedures. In consideration of the probability of the occurrence of similar problems under different surgical scenarios, most hospitals in the USA are increasingly requiring surgical patients to quit taking specific herbal products for up to 2 weeks prior to surgery, in compliance with the recommendations of the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons [1, 24, 25].

As discussed earlier with individual herbs, it is also highly probable that the risk of postoperative bleeding will be increased if analgesic drugs with antiplatelet properties, such as aspirin and certain NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen), are prescribed for pain relief to patients on blood-thinning herbal products.

Potential bleeding problem related to herbal use by dental patients can be addressed, at least in part, by implementing the principles of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine (PPPM) initiated by the European Association for PPPM in 2009 [67]. As described by the Association’s position paper, the main objective of developing this concept was to promote a paradigm change from delayed reactive medical services to evidence-based PPPM as an integrated science and health care practice.

For rationale prediction and/or prevention of the risk of herb-induced bleeding in dental settings, it is vital that adequate understanding of the pharmacology and toxicities of these natural substances by clinicians is needed. The acquisition of such knowledge is not only relevant to make informed decision for treatment, but it would also enable practitioners to better educate and instruct their patients about the potential benefits and harmful effects of herbal medications [1, 7, 9, 20]. By educating/instructing patients appropriately, potential adverse consequences of herbs can be prevented or minimized. It should also be noted that because most patients seen by health care providers are reluctant to reveal their use of herbs, efforts should be made by care givers to inquire about the use of these substances to get the necessary information for predictive and/or preventive measures [1, 7, 19, 67]. As emphasized in our previous publications [7], maintaining a record of the use of herbal products as part of a comprehensive medication history should also be recognized as important for the delivery of improved health care to patients who use these products. Another aspect of consideration is that, as expected professionally, newly encountered or suspected herbal adverse effects should also be reported to the FDA through its MedWatch Program or by any other available means for further action [1, 20, 25].

The risk of bleeding due to interactions between blood-thinning herbs and analgesic drugs (e.g., aspirin and NSAIDs) can be avoided if drugs from other pharmacological classes of analgesics, such as opioids or COX-2 selective agents (e.g., celecoxib), are prescribed [7, 24, 25]. An alternative approach can be modification of dental treatment by way of setting another date of appointment for surgery after patients have stopped taking risk-associated herb supplements for an appropriate period of time. In this regard, the recommendations of the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons noted above can serve as a guide for treating dental patients as well [1, 7, 24, 25].

The literature indicates that herbal supplement users generally reflect consistent patterns of demographic characteristics in most of the commonly utilized assessment metrics [7, 13, 14, 19]. This information can be used by clinicians to profile herbal users and predict the probability of use of herbs and thus design preemptive measures to prevent potential adverse effects, including increased bleeding tendency during treatment of patients. In connection to demography, we previously conducted a questionnaire-based survey to assess the use of herbal supplements by US adult dental patients [7]. We found that more than 60% of the supplements used by these dental patients were among the most common products used by the general US population [9, 14, 19]. By and large, similar patterns of demographic characteristics were also observed for the dental patients in our study as for the general population [7]. More specifically, we found that 48% and 31% of dental patients who used herbal supplements were in the age groups of 40–59 and 60–75 years, respectively. The rest (21%) were identified as younger users who were < 40 years of age. Women comprised 71% of herbal supplement consumers, and nearly 60% of these reported being Caucasian, followed by 32% African American. While 66% of the consumers had some college education, the majority of the rest (23%) had high school diplomas [7]. In brief, with some minor variations, these characteristics of herbal users are generally similar to those in the general population, suggesting the potential applicability of patient demographic profiles for prediction of herbal supplement use [67].

At this juncture, it also appears appropriate to reiterate that the present review is associated with certain limitations. Besides an overall scarcity of reliable information on herbal supplements, most of the biomedical data reported on these products is also based on in vitro experiments, animal studies, and individual clinical case reports. Some effects of herbal supplements are also suggested on the basis of theoretical grounds. Therefore, there may be certain flaws and inconsistencies in the reports documented in the literature on this subject area. It is generally believed that one of the major contributory factors for this problem is the 1994 US DSHEA [1, 9, 11, 14]. As an example, this Act does not apply good manufacturing practice standards to herbal supplements as required for conventional drugs [1, 14]. In short, the regulations that apply to certified health care providers and drug manufacturers that have the safety of consumers in mind do not apply to those involved in the manufacturing and provision of herbal products. Whatever the reasons may be, since herbal supplements are not properly regulated in the USA and since most of them are not well studied and standardized, there is a clear need for better regulation and further scientific investigations on these products. In addition to helping prevent/minimize potential adverse consequences, including overly bleeding in the oral cavity, the implementation of improved regulatory mechanisms and the acquisition of evidence-based information through research will allow the provision of better health care services to patients who use herbal supplements, including those that cause bleeding.

Concluding remarks

Plants have been the origin of many of the commonly used pharmaceutical drugs worldwide, and will continue to be so in the future too. In addition, these natural substances have been used as crude medicinal preparations in different cultures to provide needed health care service to millions of people globally. During the past several decades, plant products categorized as herbal supplements have been used increasingly by various segments of the US population, including dental patients. However, due to current regulation and associated factors, the safety of these products in the USA is not guaranteed. While some are used more than others, a certain portion of the commonly used herbal supplements have been reported to interfere with blood clotting. Under certain conditions, this effect of herbs can cause excessive bleeding in dental patients, such as bleeding after oral and maxillofacial surgery, and due to positive interactions with blood-thinning medications. The risks of increased bleeding under these conditions can be predicted as well as prevented with the application of the concepts of PPPM, and these measures include the acquisition of improved herbal knowledge by clinicians and patients, stopping the use of herbs prior to dental surgery, avoiding the use of blood-thinning medications with herbal products, implementation of patient demographic information for risk assessment and avoidance, and the maintenance of patients’ herbal use records, among other things. The present review also takes note of the deficiency of the US law regulating herbal supplements and the limitations of the herbal literature related to blood clotting, meanwhile emphasizing the need for improved regulation and further research on herbal products. The implementation of the measures outlined in the review may contribute to the provision of better health care services to patients who use herbal supplements with blood-thinning properties.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest in relation to the present work.

Informed consent

Patients have not been involved in relation to this work.

Human and animal rights

No experiments have been performed involving humans or animals in relation to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abebe W. An overview of herbal supplement utilization with particular emphasis on possible interactions with dental drugs and oral manifestations. J Dent Hyg. 2003;77:37–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapinova A, Stefanicka P, Kubatka P, Zubor P, Uramova S, Kello M, Mojzis J, Blahutova D, Qaradakhi T, Zulli A, Caprnda M, Danko J, Lasabova Z, Busselberg D, Kruzliak P. Are plant-based functional foods better choice against cancer than single phytochemicals? A critical review of current breast cancer research. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:1465–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hao P, Jiang F, Cheng J, Ma L, Zhang Y, Zhao Y. Traditional Chinese medicine for cardiovascular disease: evidence and potential mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2952–2966. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubey SK, Singhvi G, Krishna KV, Agnihotri T, Saha RN, Gupta G. Herbal medicines in neurodegenerative disorders: an evolutionary approach through novel drug delivery system. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2018;37:199–208. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2018027246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martel J, Ojcius DM, Chang CJ, Lin CS, Lu CC, Ko YF, Tseng SF, Lai HC, Young JD. Anti-obesogenic and antidiabetic effects of plants and mushrooms. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:149–160. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abebe W. Herbal supplements. Any relevancy to dental practice? N Y State Dent J. 2002;68:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abebe A, Herman W, Konzelman J. Herbal supplement use among adult dental patients in a USA dental school clinic: prevalence, patient demographics, and clinical implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge B, Zhang Z, Zuo Z. Updates on the clinical evidenced herb-warfarin interactions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:957362–957318. doi: 10.1155/2014/957362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marriotti AJ. Use of herbs and herbal dietary supplements in dentistry. In: Dowd FJ, Johnson BS, Marriotti AJ, editors. Pharmacology and therapeutics for dentistry. 7. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 642–647. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith T, Kawa K, Eckl V, Morton C, Stredney R. US sales of herbal supplements increase by 7.7% in 2016. Herbal Gram. 2017;115:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/. Accessed 29 Sept 2018.

- 12.Kennedy J, Wang CC, Wu CH. Patient disclosure about herb and supplement use among adults in the US. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5:451–456. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes PM, Griner EP, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States 2002. Adv Data Vital Health Stat. 34; 2004. pp. 1–20. [PubMed]

- 14.Rashrash M, Schommer JC, Brown LM. Prevalence and predictors of herbal medicine use among adults in the United States. J Patient Exp. 2017;4:108–113. doi: 10.1177/2374373517706612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dergal JM, Gold JL, Laxer DA, Lee MS, Binns MA, Lanctôt KL. Potential interactions between herbal medicines and conventional drug therapies used by older adults attending a memory clinic. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:879–886. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsen LC, Segal S, Pothied M, Bader AM. Alternative medicine use in presurgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:148–151. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparreboom A, Cox MC, Acharya MR. Herbal remedies in the United States: potential adverse interactions with anticancer agents. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2489–2503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers EA, Gough JE, Brewer KL. Are emergency department patients at risk for herb-drug interactions? Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:932–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-97: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abebe W. Herbal medication: potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:391–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall JE. Guyton & Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. Hemostasis and blood coagulation; pp. 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner GM, Stevens CW. Pharmacology. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010. pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spolarich AE, Andrews L. An examination of the bleeding complications associated with herbal supplements, antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abebe W. Herbal supplements having the potential to interfere with blood clotting. GDA Action. 2003;22:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abebe W. Herbal supplements may require modifications of dental treatments. Dent Today. 2009;28:136–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PDR . PDR for Herbal Medicines. 4. Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Review of Natural Products, 7th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health, St. Louis, Missouri; 2012.

- 28.Leung AY, Foster S. Encyclopedia of common natural ingredients used in food, drugs and cosmetics. New York, NY: J Willey and Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry R. An update of review of aleo vera. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1979;94:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, Chui PT, Aun CS, Gin T, Leau A. Possible interactions between sevolflurane and aloe vera. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1651–1654. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C, Li L, Yang L, Lǚ H, Wang S, Sun G. Anti-obesity and hypolipidemic effects of garlic oil and onion oil in rats fed a high-fat diet. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2018;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12986-018-0275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaes LPJ, Chyka RA. Interactions of warfarin with garlic, ginger, ginkgo or ginseng: nature of the evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:478–482. doi: 10.1345/aph.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bordia A. Effect of garlic on human platelet aggregation in vitro. Atherosclerosis. 1978;30:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(78)90129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rose KD, Croissant PD, Parliament CF, Levin MP. Spontaneous spinal epidural hemaroma with associated platelet dysfunction from excessive garlic ingestion: a case report. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:880–882. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199005000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burnham BE. Garlic as a possible risk for postoperative bleeding. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:213–219. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199501000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heras N, Muñoz MV, Fernández BM, Ballesteros S, Farré AL, Roso BR, Lahera V. Molecular factors involved in the hypolipidemic- and insulin-sensitizing effects of a ginger (Zingiber officinaleRoscoe) extract in rats fed a high-fat diet. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42(2):209–215. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava KC. Aqueous extract of onion, garlic and ginger inhibit platelet aggregation and alter arachidonic acid metabolism. Biomedical Biochimcal Acta. 1984;43:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bordia A, Verma SK, Srivastavs CK. Effect of ginger and fenugreek on blood lipids, blood sugar and platelet aggregation in patients with coronary heart disease. Prostaglandin, Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1977;56:379–384. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(97)90587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heck AM, DeWitt BA, Lukes AL. Potential interactions between alternative therapies and warfarin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:221–227. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.13.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lininger SW, Gaby AR, Batz F, Yarnell E, Brown DJ, Constantine G. A-Z guide to drug-herb–vitamin interactions. Rockline, CA: Prima Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller LG. Herbal medicinals: selected clinical considerations focusing on potential herb–drug interactions. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2200–2211. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung KF, Dent G, McCuster M, Guinot P, Page CP, Barnes PJ. Effect of a ginkgolide mixture (BN 52063) in antagonizing skin and platelet responses to platelet activating factor in man. Lancet. 1987;1:248–251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenblatt M, Mindel J. Spontaneous hyperema associated with ingestion of Ginkgo biloba extract. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1108–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liapina LA. A comparative study of the action of the hemostatic system of extracts from the flowers and seeds of the meadowaweet (Filipendula ulmaria L maxim) Izv Akad Nauk Series Biol. 1998;4:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajani RS, Singh P, Singh LV. Apoptotic and immunosuppressive effects of turmeric paste on 7, 12 di methyl benz (a) anthracene induced skin tumor model of wistar rat. Nutr Cancer. 2017;69:1245–1255. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1367933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srivastavs CK, Bordia A, Verma SK. Cucumin, a major component of food spice, turmeric, inhibits aggregation of and alters ecosanoid metabolism in human blood platelets. Prostaglandin Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;52:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furst DE, Sarkissian E, Blocka K. Serum concentration of salicylate and naproxen during concurrent therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;30:1157–1161. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal R, Pilote L. Research warfarin interaction with Matricaria chamomilla. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174:1281–1282. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Page RL, Lawrence JD. Potentiation of warfarin by dong quai. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:870–876. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.10.870.31558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qi-bing M, Jing-Yi T, Bo C. Advances in the pharmacological studies of Radix Angelica sincensis (OLIV) Diels (Chinese danggui) Chin Med J. 1991;104:776–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin ZZ. The effect of dong quai (Angelica sinsis) and its ingredient ferulic acid on rat platelet aggregation and release of 5-HT. Acta Pharm Sin. 1980;15:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko FN, Wu TS, Liou MJ, Huang TF, Teng CM. Inhibition of platelet thromboxane formation and phosphoinositides breakdown by osthole from Angelica pubescens. Thromb Haemost. 1989;62:996–999. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1651041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Junlie T, Huaijiun H. Effect of radix angelicae sinensis on hemorreology in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Tradit Chin Med. 1984;4:225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De La Guz JP, Martin-Ramero M, Carmona A. Effect of evening primrose oil on platelet aggregation in rabbits fed on atherogenic diet. Thromb Res. 1997;87:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(97)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuo SC, Teng CM, Lee JG, Ko FN, Chen SC, Wu TS. Anti-platelet components in planax ginseng. Planta Med. 1990;56:164–167. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim H, Lee HJ, Kim DJ, Kim TM, Moon HS, Choi H. Panax ginseng exerts antiproliferative effects on rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Nutr Res. 2013;33:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park HJ, Lee JH, Song YB, Park KH. Effects of dietary supplementation of lipophilic fraction from Panax giseng on cGMP and cAMP in rat platelets and on blood coagulation. Biol Pharm Bull. 1996;19:1434–1439. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenspan EM. Ginseng and vaginal bleeding. JAMA. 1993;249:2018–2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03330390026012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hopkins MP, Androff L, Benninghoff AS. Ginseng face cream and unexplained vaginal bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo LQ, Yamazoe Y. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 by furanocoumarins in grapefruit juice and herbal medicines. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hao X, Xiao H, Ju J, Lee MJ, Lambert JD, Yang CS. Green tea polyphenols inhibit colorectal tumorigenesis in azoxymethane-treated f344 rats. Nutr Cancer. 2017;69:623–631. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1295088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura M, Miura S, Takagaki A, Nanjo F. Hypolipidemic effects of crude green tea polysaccharide on rats, and structural features of tea polysaccharides isolated from the crude polysaccharide. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68:321–330. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2016.1232376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor JR, Wilt VM. Probable antagonism of warfarin by green tea. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:426–428. doi: 10.1345/aph.18238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubatka P, Kello M, Kajo K, Kruzliak P, Výbohová D, Mojžiš J, Adamkov M, Fialová S, Veizerová L, Zulli A, Péč M, Statelová D, Grančai D, Büsselberg D. Oregano demonstrates distinct tumor-suppressive effects in the breast carcinoma model. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:1303–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Waldron E. Natural supplements, herbs, vitamins, and food: do some prevent blood clots? Clot connect. www.clotconnect.org. Accessed 19 Sept 2018.

- 66.Cheema P, El-Mefty O, Jazieh AR. Intraoperative hemorrhage associated with the use of extract of saw palmetto herb: a case report and review of literature. J Intern Med. 2001;250:167–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Golubnitschaja O, Baban B, Boniolo G, Wang W, Bubnov R, Kapalla M, Krapfenbauer K, Mozaffari MS, Costigliola V. Medicine in the early twenty-first century: paradigm and anticipation - EPMA position paper 2016. EPMA J. 2016;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s13167-016-0072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]