Summary

Minority individuals in the United States (US) have an increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA) compared to their white/Caucasian counterparts. In general, adherence to positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy is poor and some studies suggest that PAP use among minority individuals is inferior to that of whites. However, there has not been a review of the evidence that addresses racial-ethnic disparities for PAP adherence in the treatment of OSA, and no review has systematically examined the contributing factors to poor adherence among minority individuals compared to whites.

We searched the literature for studies published between January 1990 to July 2016 that included objective PAP use comparisons between adult US minority individuals and whites. Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria. All studies compared the PAP adherence of blacks to whites. Seven studies compared the PAP adherence of additional minority groups to that of whites.

Sixteen of the 22 studies (73%) showed worse PAP adherence in blacks compared to whites. Four studies found equivalent PAP use in US Hispanics compared to whites. Little is known about the PAP adherence of other US minority groups. We present a framework and research agenda for understanding PAP use barriers among US minority individuals.

Keywords: race, ethnicity, obstructive sleep apnea, positive airway pressure, adherence, compliance, treatment, health disparities

Introduction

Positive airway pressure (PAP), the first-line therapy for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), consists of a small motorized unit, which delivers pressurized air through a hose to a mask interface, stabilizing the upper airway during sleep [1]. PAP eliminates or minimizes snoring, obstructive respiratory events, hypoxemia, autonomic arousals, and sleep fragmentation associated with OSA [1]. The benefits of PAP are dose-dependent with greater improvements derived from consistent nightly use [2, 3]. With sufficient use, PAP therapy improves daytime sleepiness and health-related quality of life and mitigates cognitive deficits, depressive symptoms, and risk for future cardiovascular events in individuals with OSA [2, 4–6]. However, using this therapy regularly can be challenging [3, 7]. Although PAP therapy is highly efficacious, the effectiveness of PAP is limited by inconsistent use [7, 8].

Regular PAP use is a complex health behavior known to be associated with individual-, disease, and treatment-level factors within biomedical, social and psychological domains [8]. Despite growing evidence that sleep beliefs and practices vary by cultural context [9], race-ethnicity has received relatively little attention in the PAP adherence literature. Furthermore, recent systematic reviews have identified increased risk for OSA among race-ethnic minorities compared to individuals of Caucasian/European descent (referred to as whites for the remainder of this manuscript) [10, 11]. The etiologies for increased risk for OSA among minority individuals are multiple and complex, but include genetic factors, craniofacial anatomical variations, increased prevalence of obesity and detrimental health behaviors (e.g. increased consumption of alcohol, lower physical activity), and the repercussions of residing in socioeconomically-deprived environments (e.g. greater pollutant exposure, less walkable neighborhoods)[11–14]. To our knowledge, the studies of Budhiraja et al and Joo and Hendegen were the first published studies to report significant differences in PAP adherence between blacks and whites [15, 16]. Although others studies have found similar results, to date, the etiology of PAP use among blacks compared to whites is not well-understood [9, 17]. Additionally, there is little data on the PAP adherence patterns of other US minority groups compared to whites [18]. By 2040, the US Census estimates that the aggregate percentage of Hispanics (26.7%), blacks (13.0%), Asians (7.1%), American Indians/Alaskans (1.2%), Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders (0.3%) and multi-racial individuals (3.2%) will nearly equal that of non-Hispanic whites (50.8%) [19]. Thus, there is a great need for a comprehensive description and understanding of the unique and shared barriers minority individuals may face for using PAP consistently and experiencing maximum benefits [9].

The purpose of this review is in line with the recommendations of a 2011 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop, “Reducing Health Disparities: The Role of Sleep Deficiency and Disorders.” This meeting highlighted the need for further research to better understand sleep disorders and their treatment across race-ethnic groups. A recent review focused on OSA and PAP treatment adherence in indigenous populations in high income countries but only included two studies addressing PAP use, both conducted in New Zealand; our review focuses on PAP adherence of race-ethnic minorities in the US [10]. Thus, the focus of this scoping review is two-fold: 1) to synthesize what is known about adherence to PAP therapy of US racial-ethnic minority individuals compared with whites and 2) to highlight gaps in the literature that frame a research agenda for PAP adherence in US minorities [20].

Methods

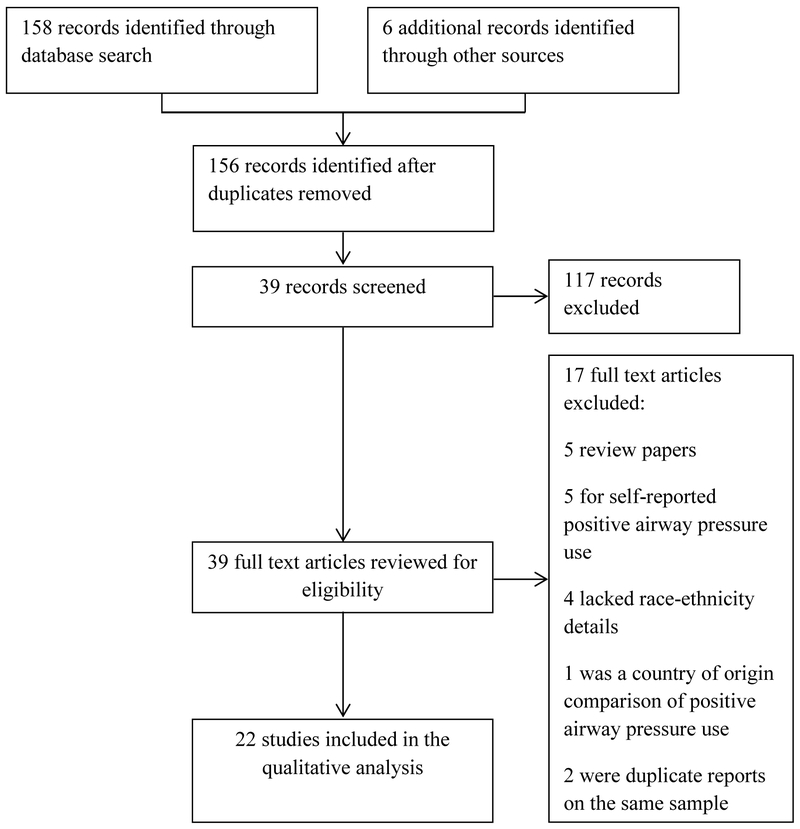

In consultation with a medical librarian, a comprehensive and systematic search was performed. We followed PRISMA guidelines to conduct this review [21]. The search was conducted in PubMed (Medline), Embase, and Web of Science Plus. OAISter, OpenGrey, and the New York Academy of Medicine databases were searched for the grey literature. The search strategy was constructed using the MeSH database and other appropriate thesauri to develop a thorough search strategy of key words and subject headings (see Supplement). Key search terms included “sleep apnea” or “sleep disordered breathing” and “positive airway pressure” and “race” or “ethnicity,” and “adherence” or “compliance”. Since the early 1990s, PAP devices have had the capability to record objective, nightly PAP usage [22]. Thus, the search date spanned January 1990 to July 2016. A total of 158 articles were initially retrieved (Figure 1). For the sake of completeness, the lead author (DMW) searched the major sleep journals including SLEEP, the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, Sleep Medicine, Behavioral Sleep Medicine, CHEST, and Sleep and Breathing. This resulted in one additional article. We also conducted ancestry search of all retrieved articles’ references lists which resulted in an additional five articles for initial review.

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow diagram

Articles that met criteria for the review included those that were: 1) primary studies; 2) published in peer review journals; 3) written in English; 4) included only adults; 5) included objective PAP adherence data; and 6) included a US minority group to white comparison. Abstracts were included if they were published within the past five years. If an article did not provide sufficient data with regard to race/ethnicity, DMW contacted the author via email. If no response was received, the article was excluded.

Two authors (DMW and NJW) independently reviewed the titles followed by the abstract of each article. Those articles that met the inclusion criteria (n=39) were fully, independently reviewed for additional information by the authors (DMW and NJW). With full review, 17 additional studies were excluded. Article tracking software (COVIDENCE) was used to manage the retrieved literature. The final evidence set for analysis was independently evaluated by two authors (DMW and AMS) for level and quality of evidence using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Research Evidence Appraisal tool [23]; discrepancies were discussed and mutually-agreed final ratings were established.

This review is registered at PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). The 22 included studies were grouped based on the race-ethnic comparison, and then by studies that reported adjusted and unadjusted results. Twenty-two studies compared PAP use between blacks and whites. Seven studies included additional comparisons: Hispanic to white (n=4), Asian/Pacific Islander to white (n=3), American Indian/Alaskan to white (n=1), and “other” race-ethnicity to white (n=4).

Results

Description of all studies comparing PAP use in minority groups to whites

The characteristics of the studies comparing PAP use in blacks to whites (n=22) are presented in Tables 1 and 2; the studies comparing PAP adherence of additional minority groups to whites (n=7; not mutually exclusive) are presented in Table 3. For the entire set of evidence (n=22), seven were cohort studies and 15 studies were retrospective cohort studies. All, but two, studies were conducted in single-site outpatient, sleep centers [24, 25]. The Home-PAP cohort study included seven sleep center sites in five US cities while the Sawyer et al cohort study recruited participants in two sleep centers [24, 25]. All studies had a non-experimental level of evidence and 45% (n=10) were of low quality. The majority of studies included predominantly male, PAP-naïve individuals with moderate-severe OSA. The study sample sizes ranged from 30–2,172 individuals with 50% of studies (n=11) consisting of sample sizes of less than 100 individuals. The number and frequency of minority groups varied across included studies but all studies (n=22) included PAP adherence comparisons between blacks (sample composition, 883%) and whites. Additionally, four of the 22 studies included PAP adherence comparisons between Hispanics (sample composition, 9–25%) and whites [16, 18, 24, 25] and three studies compared PAP use in Asians/Pacific Islanders (1–7%) to whites [16, 25, 26]. One study reported PAP use comparisons in individuals of American Indian/Alaskan descent to whites [25]. Four studies reported PAP adherence of an aggregated “other” race-ethnicity category relative to whites [24, 26–28]. In six studies [29–34], the racial reference group was non-black (aggregated groups consisting of whites, white individuals of Hispanic ethnicity, and other racial-ethnic categories).

Table 1:

US studies examining unadjusted PAP adherence of blacks to whites/non-blacks

| Study (Level & Quality rating) | Design/setting | Sample with PAP data | Minority/reference group (%) | Outcome interval | Adherence outcome(s) | Analysis methods | Results blacks vs whites/non-blacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budhiraja et al 2007 [15] (III B) |

Retrospective cohort; single sleep center, Detroit, MI | N=100, 65% men; PAP-naive | black (39%) white (57%) | Initial 30 days | Mean daily use | Student t test | 4.4 ± 1.2 hrs vs 5.5 ± 2.2 hrs, p<0.01 |

| Somiah et al 2012 [26] (III B) | Cohort; single sleep center, New York, NY. | N=93, 66% men; PAP-naive | black (27%) white (40%) | Initial two weeks | < 2hrs/daily vs 2–4 hrs/daily

vs > 4 hrs/daily |

Chi-square test | No difference |

| Burke et al 2014 [28] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; Telemedicine-based sleep clinic; Charlotte, NC | N=30, 57% men; PAP-naïve; 1 Bilevel PAP | black (83%) white (13%) | Not reported | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Fisher’s exact test | No difference |

| Sawyer et al 2014 [25] (III C) | Cohort; two sleep centers; Hershey, PA and Wilmington, DE | N=79, 54% men; PAP-naive | black (8%) white (85%) | Initial 30 days | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Fisher’s exact test | No difference |

| Altememi et al 2015 [36] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center; Baltimore, MD | N=30, 57% men; PAP-naive |

black (53%) white (47%) | Initial 6–8 weeks | ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days | Chi square test | 19% vs 79% adherent, p<0.01 |

| DelRosso et al 2015 [37] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center, Shreveport, LA | N=30, 33% men; PAP-naive | black (60%) white (37%) | Initial months 1,3,6, and 9 | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Chi square test |

1 month: 28% vs 62% adherent, p=0.02 3, 6, & 9 months: No difference |

| Dudley et al 2015 [38] (III C) | Cohort; single sleep center, Boston, MA | N=33, 36% men; existing users | black (58%) white (42%) | 30 days prior to visit | ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days | Chi square test | 26% vs 64% adherent, p<0.01 |

| Colvin et al 2016 [35] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center, St Louis, MO | N=53, 76% men; PAP-naïve; 19% APAP; CMV drivers | black (77%) white (23%) | Initial week, and months 1, 3, 6, and 12 | ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days | Logistic regression | No difference |

| Sharma et al 2016 [39] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center; Philadelphia, PA | N=80, 56% men; Bilevel PAP and ASV; Inpatients with CHF | black (45%) white (55%) | Initial 3,6, and 12 months | ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days | Chi square test |

3 months: 32% vs 68% adherent, p=0.01 6 & 12 months: No difference |

Study level of evidence: I, experimental; II, quasi-experimental; III, non-experimental. Study quality rating: A, high; B, good; C, low. Minority and reference group % do not add to 100% for studies involving > 2 race-ethnic groups. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; APAP, autoadjusting positive airway pressure; ASV, adapto-servo ventilation; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; CMV, commercial motor vehicle; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PAP, positive airway pressure

Table 2:

US studies examining adjusted PAP adherence of blacks to whites/non-blacks

| Study (Level & Quality rating) | Design/setting | Sample with PAP data | Minority/reference group (%) | Outcome interval | Adherence outcome(s) | Analysis methods | Covariates | Results blacks vs whites/non-blacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joo & Herdegen 2007 [16] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center; Chicago, IL |

N=323, 49% men; PAP-naive | black (75%) white (6%) | Initial 30 days | < 4 hrs daily | Multivariable logistic regression | sex, BMI | blacks OR 5.5 (95%CI: 1.5–20.1), non-adherent |

| Platt et al 2009 [27] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep center; Philadelphia, PA | N=266, 94% men; PAP-naïve; APAPs | black (50%) white (42%) | Daily over the initial week | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Multivariable logistic regression | Age, marital status, employment, comorbidities, neighborhood SES index | blacks OR 1.2 (95%CI: 0.8–1.8), adherent |

| Means et al 2010 [41] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep center; Durham, NC | N=499, 95% men; PAP-naive | black (41%) white (59%) | Initial months 1 and 3 | a) Mean daily use; b) % days used |

ANCOVA with post-hoc | Age, BMI, respiratory disturbance index |

1 month: a) 3.9 ±2.0 hrs vs 5.0 ±2.1 hrs, p<0.001; b) 62% vs 73%, p<0.001 3 months: a) 3.9 ± 1.9 hrs vs 4.9 ±2.1 hrs, p<0.001 b) 54% vs 68%, p<0.001; |

| Sawyer et al 2011 [34] (III C) | Cohort; single VA sleep center; Philadelphia, PA | N=66, 97% men; PAP-naive | black (45%) white (52%) | Initial week and 1 month | Mean daily use | Stepwise linear regression | Post-education self-efficacy, 1 week self-efficacy | 1.5 hours less use, p=0.02 |

| Moran et al 2011 [40] (III C) | Cohort; single sleep center; Greenville, NC | N=63, 49% men; PAP-naïve; 15%Bilevel PAP 10% APAP | black (35%) white (65%) | First adherence download (range 30–171 days) | ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days | Multivariable logistic regression | Personality traits, motivation style, coping strategies | No difference |

| Billings et al 2011 [24] (III B) | Cohort; 7 sleep centers in 5 US cities (Chicago, Madison, Minneapolis, Seattle, Cleveland) | N=145, 65% men; PAP-naïve; APAPs | black (22%) white (62%) | Initial months l and 3 | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | AHI quartiles, Zip code SES, Study arm (home vs in-lab study) |

1 month: blacks 92 mins less use, p<0.01; 3 months: blacks 68 mins less use, p=0.06 |

| Pamidi et al 2012 [29] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center; Chicago, IL | N=403, 47% men; PAP-naive | black (54%) non-black (46%) | Initial 30 days | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | Age, sex, BMI, education, AHI, sleepiness, depression, Medicaid status, sleep doctor referral | 56 mins less use, p<0.01 |

| Ye et al 2012 [33] (III C) | Cohort; single sleep center; Philadelphia, PA | N=91, 54% men; PAP-naive | black (57%) white (42%) | Initial week | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | Download residual AHI, intimacy difficulties | 96 mins less use, p<0.05 |

| Guralnick et al 2012 [30] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; single perioperative clinic; Chicago, IL | N=104, 62% men; PAP-naïve; 100% APAP | black (57%) non-black (43%) | Initial 30 days | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | sex, education, OSA severity, sleepiness, depression | 68 mins less use, p=0.02 |

| Balanchandran et al 2013[31] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center, Chicago, IL | N=403, 47% men; PAP-naive | black (54%) non-black (46%) | Initial 30 days | Mean daily use | Stepwise linear regression | Non-sleep specialist ordering PSG and CPAP perception | 46 mins less use, p<0.01 |

| Wallace et al 2013 [18] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep center; Miami, FL | N=248, 94% men; PAP-naïve and existing users | black (38%) white (37%) | Initial distribution until study clinic visit: mean 1.4 ± 1.3 yrs | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | Age, BMI, education, treatment duration, insomnia, self-efficacy | blacks 61 mins lower use, p<0.01 |

| Wallace et al 2015 [32] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; Single VA sleep center; Miami, FL | N=315 91% men; PAP-naïve; APAPs and Bilevel PAPs | black (43%) white (57%) | Initial 12 weeks; weekly averages |

Mean daily use; Daily use as % of total sleep time | Longitudinal multi-level modeling | Age, BMI, AHI, comorbidities, PAP pressure, sleepiness |

1 week: No difference (mean use; use as % TST) 12 weeks: No difference in rate of change (use as % TST) |

| Schwartz et al 2016 [42] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep center

Tampa, FL |

N=2172, 96% men; PAP-naïve and existing users; 10% Bilevel PAPs | black (11%) white (89%) | Initial 2 weeks and 6 months | a) ≥ 4 hrs daily; b) ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days |

Multivariate log-linear risk models | Age, sex, marital status, BMI, comorbidities, OSA severity, oxygen nadir, sleepiness, household income |

2 weeks: a) RR 0.63, b) RR 0.58, p<0.001; 6 months: a) RR 0.56, b) RR 0.56, p<0.001 |

Study level of evidence: I, experimental; II, quasi-experimental; III, non-experimental. Study quality rating: A, high; B, good; C, low. Minority and reference group % do not add to 100% for studies involving > 2 race-ethnic groups. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; APAP, autoadjusting positive airway pressure; BMI, body mass index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PAP, positive airway pressure; PSG, polysomnography; RR, risk ratio; TST, total sleep time; VA, Veterans Administration.

Table 3:

US studies comparing PAP adherence of other minority groups to whites

| Study (Level & Quality rating) | Design/setting | Sample with PAP data; treatment | Minority/reference group (%) | Outcome interval | Adherence outcome(s) | Analysis methods | Covariates | Results minority group vs whites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joo & Herdegen 2007 [16] (III B) | Retrospective cohort; single sleep center; Chicago, IL | N=323, 49% men; PAP-naive | Hispanic (15%) Asian/Pacific islander: (2%) white (6%) | Initial 30 days | < 4 hrs daily | Multivariable logistic regression | sex, BMI | No difference |

| Platt et al 2009 [27] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep center; Philadelphia, PA | N=266, 94% men; PAP-naïve; APAPs | other (9%) white (42%) | Daily over the initial week | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Multivariable logistic regression | Age, marital status, employment, comorbidities, neighborhood SES index | other OR 1.1 (95% CI:0.6–2.1), adherent |

| Billings et al 2011 [24] (III B) | Cohort; 7 sleep centers (Chicago, Madison, Minneapolis, Seattle, Cleveland) | N=145, 65% men; PAP-naïve; APAPs | Hispanic (9%) other (6%) white (62%) | Initial months 1 and 3 | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | AHI quartiles, Zip code SES, Study arm (home vs in-lab study) |

1

month: Hispanics 4 mins less use, p=0.92 3 months: Hispanics 27 mins more use, p=0.36 |

| Somiah et al 2012 [26] (III B) | Cohort; single sleep center, New York, NY. | N=93, 66%, men; PAP-naive | Asian (7%) other (17%) NR (9%) white (40%) | Initial two weeks | < 2hrs/daily vs 2–4 hrs/daily vs > 4 hrs/daily | Chi-square test | None | No difference |

| Wallace et al 2013 [18] (III A) | Retrospective cohort; single VA sleep

center; Miami, FL |

N=248, 94% men; PAP-naïve and existing users | Hispanic (25%) white (37%) | Initial distribution until study clinic visit: mean 1.4 ± 1.3 yrs | Mean daily use | Multivariable linear regression | Age, BMI, education, treatment duration, insomnia, self-efficacy | Hispanics 8 mins lower use, p=0.75 |

| Burke et al 2014 [28] (III C) | Retrospective cohort; Telemedicine-based sleep clinic; Charlotte, NC | N=30, 57% men; PAP-naïve; 1 Bilevel PAP | other (3%) white (13%) | Not reported | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Fisher’s exact test | None | No difference |

| Sawyer et al 2014 [25] (III C) | Cohort; two sleep centers; Hershey, PA and Wilmington, DE | N=79, 54% men; PAP-naive | Hispanic (9%) Asian (1%) Pacific islander (3%) American Indian/Alaskan native (4%) white (76%) | Initial 30 days | ≥ 4 hrs daily | Fisher’s exact test | None | No difference |

Study level of evidence: I, experimental; II, quasi-experimental; III, non-experimental. Study quality rating: A, high; B, good; C, low. Minority and reference group % do not add to 100% as black group not included. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; APAP, auto-adjusting positive airway pressure; BMI, body mass index; NR, not reported; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PAP, positive airway pressure; SES, socioeconomic status; VA, Veterans Administration.

Most studies (73%) examined individuals treated with fixed continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy while others also included individuals treated with auto-adjusting positive airway pressure (APAP; n=6), bilevel PAP (n=5), or adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) devices (n=1). There was large variation in the duration of therapy ranging from seven days to a mean of 18 months. PAP use outcome operational definitions varied across studies, with some studies using a continuous outcomes (i.e. mean use for defined outcome interval) while others used categorical definitions of adherence (e.g. ≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days).

Black race and PAP adherence: Unadjusted analyses

Nine studies reported unadjusted black-white PAP adherence comparisons with four studies identifying no significant racial differences in PAP use (Table 1). In a cohort study investigating whether PAP titration sleep architecture predicted future PAP use [26], Somiah et al did not find black-white differences in the frequency of adherence during the first two weeks of treatment (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 32% [black] vs 38% [white], p=0.64 [calculated outside of article]). In a telemedicine-based clinic sample providing sleep services to uninsured or low-income individuals [28], Burke et al also did not find any significant racial differences in the frequency of PAP adherence (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 52% [black] vs 25% [white]; p=0.60). However, only 30 subjects had complete objective PAP adherence data available for analysis [28]. In another cohort study focusing on the relationship between pretreatment sleep schedule regularity and PAP adherence [25], Sawyer et al did not identify significant black-white differences in frequency of one month treatment adherence (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 83% [black] vs 60% [white]; p=0.40). Similarly, Colvin et al did not identify significant race-ethnic PAP use differences in a study of individuals referred to a sleep center for commercial motor vehicle driver evaluations [35], though this sample may not be reflective of general clinical sleep center populations. In this study, blacks had non-significant (p = 0.11) higher frequency of adequate PAP adherence (≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days) than whites at one week (72% vs 28%), 1 month (74% vs 27%), 3 months (70% vs 30%), and 12 months (76% vs 24%).

The remaining five unadjusted comparison studies found that blacks had significantly lower PAP use compared to whites at 30 days to three months. Budhiraja et al showed that, on average, blacks used PAP one hour less than whites (4.4 ± 1.2 hrs vs 5.5 ± 2.2 hrs, p<0.01) after one month of treatment [15]. Altememi et al (n=30) found that blacks were less adherent to PAP than whites (≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days; 19% vs 79%, respectively, p<0.01) after returning to a sleep clinic at 6–8 weeks of treatment [36]. In another small study which provided PAP at no cost to uninsured individuals (n=30), Del Rosso et al showed that blacks had lower frequency of PAP adherence than whites (≥ 4 hrs daily; 28% vs 62%, respectively, p=0.02) after one month of therapy [37]. Although this study followed subjects (n=11) for nine months, attrition limited PAP use comparisons by race beyond the one month study interval. In a study of experienced users returning to a sleep clinic, Dudley et al showed that blacks had lower PAP adherence than whites (≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days; 26% vs 64%, respectively, p<0.01) in the 30 days preceding the clinic visit [38]. Finally, in a sample of hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure exacerbation treated with bilevel PAP or ASV treatment [39], blacks had lower frequency of regular PAP use than whites (≥ 4 hrs daily on ≥ 70% days; 32% vs 68%, respectively, p=0.01) after three months of therapy.

Black race and PAP adherence: Adjusted analyses

Thirteen studies reported adjusted race-ethnic PAP adherence comparisons between blacks and whites/non-blacks; only two studies did not detect significant racial differences in PAP use (Table 2) [27, 40]. Commonly used covariates included demographic and psychosocial factors, health/comorbidities, and disease/treatment related factors such as apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and residual AHI. In a cohort study (n=63) adjusting for psychosocial factors including personality traits, coping, and motivation style [40], Moran et al found that black participants were 0.35 times as likely (p=0.17) to be adherent to PAP than white individuals. In a retrospective study of veterans treated at the Philadelphia VA [27], Platt et al (n=266) examined if neighborhood SES was associated with PAP use over the initial seven days of therapy. After adjustment for age, marital status, medical comorbidities, employment status, and neighborhood SES index, the odds of PAP adherence for black veterans was similar to that of white veterans (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.6–1.2). Living in a poorer neighborhood, but not race, was associated with lower PAP use over the first week of treatment. Moreover, the relationship between neighborhood SES index and PAP adherence did not vary by race.

The remaining 11 studies found significant black-white differences in PAP use. Joo and Hendersen (n=323) examined PAP non-adherence over the first month of treatment in a Chicago public hospital wherein 73% of the sample lacked insurance [16]. After controlling for gender and body mass index (BMI), blacks were 5.5 times more likely to be non-adherent to PAP therapy (< 4 hrs daily) compared to whites (OR 5.5; 95% CI: 1.5–20.1); However, this study included few whites (n=18), which contributes to the imprecise estimate (i.e., wide CI). After adjusting for residual apnea-hypopnea index and a single side effect (intimacy difficulties), Ye et al (n=91) found that blacks used PAP 96 mins less than whites (p<0.05) after one week of therapy [33]. In a cohort study adjusting for self-efficacy after the first week of treatment [34], Sawyer et al (n=66) found that blacks had 1.5 ± 0.6 hrs lower mean daily PAP use than whites at one month. Wallace et al (n=315) described PAP use trajectories over the first 12 weeks of treatment while adjusting for age, BMI, AHI, comorbidities, sleepiness, and treatment pressure [32]. Using raw daily PAP use averaged over the first 12 weeks, black race predicted less PAP use (61 mins) at week one compared to whites (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) and worse diminishing use at week one (−16 mins/wk vs −9 mins/wk, respectively, p=0.03). There were, however, no significant racial differences in the rate of change of PAP use over 12 weeks. With standardized PAP use (mean daily PAP as a % of baseline total sleep time [TST]), PAP use (%) in blacks did not differ significantly from whites during week one of treatment (whites 83% TST vs blacks 67% of TST; p=0.21), nor did the rate of change differ between races over the 12-week treatment period.

Controlling for age, BMI, and OSA severity, Means et al (n=499) showed that black veterans used PAP significantly less (one less day per week and one hour less per day) at one month and three months compared to white veterans [41]. In the Home-PAP study, a randomized, controlled study in five US cities comparing home-based diagnosis and PAP titration to in-lab care [24], Billings et al assessed PAP use after providing PAP therapy at no-cost to participants (n=145). After adjusting for OSA severity, study arm, and residential socioeconomic status (SES), blacks, on average, used PAP 92 minutes less daily than white participants after one month of therapy (p<0.01). However, after three months of treatment, this finding was attenuated (n=129; −68 mins, p=0.06), potentially from loss of power related to greater attrition of black subjects. Pamidi et al (n=403) examined the influence of a sleep specialist consultation prior to sleep testing on future PAP use [29]. Adjusting for several covariates including age, education, sex, BMI, AHI, sleepiness, Medicaid status, depressive symptoms, and sleep specialist consultation, black race was associated with approximately 56 mins lower mean daily PAP use relative to non-black race (p=0.002) during the initial month of therapy [29]. In another study examining a short questionnaire about PAP therapy perception completed after titration PSG [31], Balachandran et al (n=403) reported that more negative first impressions about PAP (p=0.005), black race (p=0.007), and having the PSG ordered by a non-sleep specialist (p<0.001) were associated with worse PAP use at one month. When adjusting for immediate impression about PAP therapy and sleep specialist status, black race was associated with an average 46 minutes less daily PAP usage than non-black race (p=0.007) after one month of therapy. Additional adjustments for habitual sleep duration, PSG type (full vs split night), and average leak did not change these relationships. In addition, the relationship between the PAP perception score and PAP adherence did not vary by race.

In a different clinical setting, a perioperative clinic, Guralnick et al performed split-night PSGs in patients at high-risk for OSA [30]. Patients with moderate to severe OSA were provided auto-adjusting PAP units prior to their elective surgery. Objective adherence was assessed (n=104) at an initial consultation with a sleep physician 6–8 weeks later. After adjusting for gender, educational attainment, OSA severity, subjective sleepiness, and depressive symptoms, black race was associated with 68 minutes less daily PAP adherence at one month compared to non-black participants (p=0.02). In a study of existing PAP users returning for clinical follow at the Miami VA sleep clinic [18], Wallace et al (n=248) examined the association of race-ethnicity with PAP use and investigated whether the relationship of previously described biomedical (age, PAP pressure, insomnia) and psychological (self-efficacy) variables associated with PAP adherence were moderated by race. After adjustment for several factors (age, BMI, comorbid insomnia, treatment duration, education, and self-efficacy), blacks used PAP one hour less than whites after a mean treatment duration of 1.4 ± 1.3 years. Although the influence of PAP pressure, insomnia, and self-efficacy were equivalent across racial groups, the relationship between age and daily PAP use varied by race. While older age was associated with greater mean daily PAP use among whites, younger age was associated with greater daily PAP use among blacks. In the largest retrospective study examining race-ethnicity and PAP adherence to date [42], Schwartz et al (n=2,172; 233 blacks) found that black veterans were about half as likely as white veterans to use PAP ≥ 4 hrs daily on 70% of day during the initial two weeks (RR 0.58 95% CI: 0.43–0.77) and after six months of therapy (RR 0.52 95% CI 0.36–0.74). These findings were independent of several covariates including age, gender, BMI, OSA severity, oxygen nadir, sleepiness, marital status, and median neighborhood income. In addition, the authors found that the relationship between OSA severity and PAP use was moderated by race. In contrast to white veterans who showed a weaker positive relationship between OSA severity and PAP use, black veterans with severe OSA were three times more likely to adhere to PAP than black veterans with mild-to-moderate OSA.

Other race-ethnic groups and PAP adherence: Unadjusted analyses

Three studies reported unadjusted PAP use comparisons of other racial-ethnic groups to whites (Table 3). In the cohort study of Somiah et al [26], no race-ethnic difference in the frequency of PAP adherence was observed between participants of “other” race-ethnicity and whites over the first two weeks (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 52% [“other” race-ethnicity] vs 38% [white]; p=0.28). The “other” race-ethnic category aggregated seven Asian, one American Indian, two biracial, and 19 Hispanic individuals (personal communication). Similarly, in the telemedicine-based study of Burke et al [28], there was no significant difference in the frequency of PAP adherence in one subject of “other” race-ethnicity relative to that of whites (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 0% [“other” race] vs 25% [white]; p=1.0). The cohort study of Sawyer et al also reported no significant race-ethnic differences in frequency of adherent status after one month of therapy (within-group % ≥ 4 hrs daily adherence, 29% [Hispanic] vs 63% [non-Hispanic white], p=0.11; 100% [Asian] vs 60% [white] p=1.0; 0% [Hawaiian/Pacific Islander] vs 60% [white], p=0.17; 67% [American Indian/Alaskan native] vs 60% [white], p=1.0) [25]. These three small studies, inclusive of unbalanced “other” race-ethnic sample categories, did not detect PAP adherence that differed from that of white participants.

Other race-ethnic groups and PAP adherence: Adjusted analyses

None of the four studies comparing the adjusted PAP use of additional race-ethnic groups to whites found significant differences (see Table 3 for specific covariates). With the caveat of having few participants of Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander origin, Joo and Hendersen did not find additional racial-ethnic disparities in PAP non-adherence after 30 days of therapy (nonadherence ORs for these groups not reported) [16]. Similarly, Platt et al reported that the odds of PAP adherence for individuals of “other” races was similar to that of white veterans over the initial 7 days of therapy (OR 1.0 95% CI 0.5–1.7) [27]. The “other” racial category included seven individuals of Pacific Islander, Asian, or American Indian background and 16 participants not reporting race. In the Home-PAP cohort study [24], there were no significant mean daily PAP use differences between Hispanic and white individuals at one and three months (one month:- 4 mins, p=0.92; three month: 27 mins, p=0.36). Among existing PAP users [18], Wallace et al reported that the estimated mean daily PAP use of Hispanic veterans (25% of sample) was similar to that of white veterans after a mean of 1.4 years since PAP initiation (−8 mins, p=0.75).

Discussion

Our review provides evidence that some, but not all, racial/ethnic individuals living in the US have lower adherence to PAP than white individuals, using objective measures of adherence. Most existing studies are of modest evidence level and quality with limitations including retrospective designs, sleep center settings, and unbalanced, convenience samples. The most comprehensive data exists for US blacks, wherein 16 of 22 studies showed significantly lower PAP use compared to whites. The majority of studies included relatively small sample sizes with the largest study including 233 blacks [42]. Despite adjusting for several covariates, an average of approximately one hour lower mean daily PAP usage persisted between blacks and whites in varied clinical and research settings [18, 24, 41]. In addition, blacks also attempted to use PAP on significantly fewer nights compared to whites [18, 24, 41]. Of the six studies that did not find that blacks used PAP less than whites, all but one had small sample sizes, providing less stable estimates.

All four studies that compared PAP adherence in US Hispanics to whites showed equivalent PAP adherence among experienced and PAP-naïve users [16, 18, 24, 25]. Furthermore, none of these studies reported the level of acculturation (extent of adoption of US cultural practices) of their Hispanic participants, which is salient as acculturation has been associated with deleterious health behaviors and worse sleep parameters [43]. The largest study including Hispanics consisted of veterans, a population which has few healthcare access barriers, and is known to be highly acculturated [18, 44]. Three studies did not find significant differences in the PAP use of Asian/Pacific Islanders and whites [16, 25, 26]. However, these studies had small sample sizes with a total of 15 Asian/Pacific Islanders. Similarly, one study provided an unadjusted comparison between American Indian/Alaskan individuals (n=3) and whites, finding no significant differences in PAP use [25].

There is a significant body of evidence that explores the deleterious effects of poor adherence to PAP [8], as well as a number of investigations exploring the underlying mechanisms of suboptimal adherence. Yet, there is a paucity of adherence data for racial-ethnic minority populations. This is striking given the higher prevalence of OSA and higher burden of OSA-related morbidity in these groups compared to whites [10–13]. In the Jackson Heart Study, 17% of black women and 4% of black men reported symptoms consistent with OSA [45]. Although the estimates for black men is equivalent to that reported for white men (4%), the estimates for black women (17%) far exceeds the estimates for white women (2%) [46]. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Chinese individuals were 1.6 times more likely to have severe OSA as white individuals [47]. Similarly, American Indians have been found to have a higher prevalence of mild OSA (AHI 5–14) (33% vs 29%) and moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI ≥ 15) (23% vs 17%) compared to whites [46]. Finally, in the Hispanic Community Health Study, the largest study of US Hispanics (n=14,440), the prevalence of mild OSA and moderate-to-severe OSA was 25.8% and 9.8%, respectively [12].

The etiology of PAP use disparities may be complex and multi-layered [8]. In Unequal Treatment, the Institute of Medicine’s report on racial and ethnic health disparities in healthcare, individual-level, provider-level, and healthcare system-level barriers were found to contribute to racial-ethnic disparities in medicine [48]. We utilize this framework to not only focus on black-white disparities in PAP adherence but also discuss shared barriers for other understudied minority groups.

Individual-level factors

Knowledge and attitudes about OSA could influence adherence among minority patients [34]. In focus groups performed in Brooklyn, blacks reported that OSA symptoms (i.e. apneas, daytime sleepiness) were a result of meal consumption or were confused with early insomnia (i.e. inability to fall asleep) [49]. It is unclear whether these misattributions of OSA symptoms vary by race-ethnicity as similar studies have not been conducted with white, black and other US minority individuals. Motivation to pursue and persevere with PAP treatment may partially hinge on recognition of poor quality sleep and OSA symptoms as a serious medical problem. In 2010, the Sleep in America Poll by the National Sleep Foundation showed that black and Hispanic respondents were less likely to recognize that poor or curtailed sleep was linked to health problems than white respondents [50]. This may partially explain the race by OSA severity interaction reported by Schwartz et al. In contrast to white individuals, black veterans with severe OSA were three times more likely to use PAP than veterans with mild-to-moderate disease [42]. Thus, blacks with milder degree of OSA may consider OSA of less importance or differentially perceive the benefits of PAP than white individuals [51]. Variable cultural sleep norms and practices (e.g. bed-sharing, pre-sleep activities) may also pose challenges for consistent PAP therapy among minority individuals [9]. As minority individuals may be unfamiliar with this treatment [12], PAP units may be confused with ventilators and perceived as therapy for serious illness. For example, in clinical research studies where care is provided at no cost to participants, acceptance of PAP therapy (i.e., acquiring the equipment with the intention of using it regardless of actual usage) was significantly lower in blacks compared to whites (83% vs 94%, p<0.001) [24]. Similarly, in a study from Los Angeles with low-income and uninsured individuals diagnosed with OSA, Hispanics were much less likely to accept PAP therapy PAP than whites (54% vs 83%, p<0.005) [52]. Finally, trust in medical providers and health literacy may be important for adherence to PAP [53]. Due to historical transgressions, blacks may be more suspicious of physician recommendations relative to whites and label an unfamiliar treatment as “experimental” [48, 54, 61]. Although one study in New Zealand did not find that health literacy predicted PAP use differences between Maori and individuals of European descent, very little work has been done in this area with US minority individuals [55]. One small US study (n=30) did not find significant differences in health literacy between black and white individuals treated with PAP [38]; however, more comprehensive assessments of these constructs need to be investigated with larger US minority groups.

Medical and sleep comorbidities may influence differential PAP use among minority individuals. For example, Means et al described that mental health symptoms impacted PAP use adversely among black but not white veterans [41]. Comorbid with depression or other mental health symptoms, the demands of regular PAP use may prove more overwhelming for minority individuals [30, 41]. Importantly, only two of the reviewed studies controlled for depressive symptoms in the PAP use comparisons. In addition, comorbid insomnia symptoms and shift work are more common among US minority than in white individuals [17, 18, 56]. For example, during initiation of PAP therapy or at follow up visits, blacks have reported more comorbid sleep onset insomnia symptoms compared to whites [17, 18]. Directly, these sleep comorbidities may make acclimatization to therapy more difficult (less regularity of sleep routines) and contribute to lower habitual sleep times (i.e. less opportunity in which to use PAP) [25]. Shorter sleep duration among blacks has been found to explain a small portion of the one hour mean daily difference in PAP use between blacks and whites. In a mediational analysis of the multi-city Home PAP study, Billings et al showed that reduced sleep duration in blacks mediated 11 mins of lower mean daily PAP adherence at three months [17]. More studies are needed to investigate whether sleep duration and other sleep routine factors may be obstacles for regular PAP adherence among other US minority groups.

The least well-studied barriers contributing to differential PAP use among minority individuals are categorized in the social and psychological domains. In general, supportive relationships with bed-partners or peers have been linked to greater PAP adherence [57, 58]. In the Sleep in America poll, blacks (41%), Asians (37%), and Hispanics (31%) reported sleeping alone significantly more often than white individuals (21%) [50]. Thus, minority individuals may have less of an opportunity to rely on bed-partners to remind them to wear PAP or help with equipment issues (i.e. mask leaks, removing the mask during sleep). In addition, minority individuals have different social demands competing for their time, potentially reducing opportunities to sleep and thereby PAP use time. For example, US Hispanics, blacks, and Asians are more likely to care for family members, work more than one job, and work longer hours than their white counterparts [56, 59, 60]. Several psychological constructs recognized as key determinants of PAP adherence have not been well studied in US minorities. Self-efficacy, or an individual’s confidence to use PAP despite its challenges, was found to have equivalent relationships with PAP use (i.e. self-efficacy positively associated with daily PAP use) among experienced white, black, and Hispanic users [18]. However, self-efficacy has not been compared in PAP-naïve US minority individuals. Similarly, coping style, another important psychological construct linked to PAP use, has not been studied in US minority individuals [8]. This may be particularly salient as minority individuals (including recent immigrants) are subject to unique chronic stressors including perceived discrimination, racism, and acculturation to the US lifestyle, all of which have been associated with greater sleep complaints, worse sleep quality, and worse objective sleep continuity [43, 61, 62]. Compared to whites whose sleep duration improves with higher occupational attainment, US-born and immigrant black and Hispanic individuals have an increasing prevalence of short sleep duration associated with increasing professional/management positions [59, 63, 64]. Finally, living in stressful environments which are less conducive to restful sleep (i.e. neighborhoods with greater levels of noise, violence, and crowding) may contribute to the perception that PAP therapy is less effective among minority individuals [65, 66]. As symptomatic improvement is one of the strongest predictors of continued PAP use [3, 8], curtailed or persistent poor quality sleep despite PAP treatment may contribute to intermittent use or abandonment of therapy among minorities.

Socioeconomic barriers to PAP use may be more common among US minority individuals relative to whites. Lower SES individuals may experience difficulties with (1) transportation, (2) communicating with providers, (3) stable housing with electricity, and/or (4) prioritizing PAP use given competing financial demands [24, 27, 37]. Studies have tried to address whether race-ethnicity itself or its relationship with lower socioeconomic status is associated with differential PAP use. However, this has been complicated by the high correlation of race-ethnicity and SES and small sample sizes [24]. Platt et al failed to find that veteran race was associated to PAP over the first week of treatment after adjusting for residential SES index [27]. However, this study also adjusted for employment status, an individual-level SES factor, and may have had SES range restriction given Veteran Administration guidelines of serving veterans with constrained resources. The much larger study of Schwartz et al did disentangle the association between PAP use and median neighborhood SES finding that neighborhood-based income estimates had little influence of the relationship between race and PAP use [42]. Thus, neighborhood SES barriers alone do not fully explain black-white racial differences in PAP adherence. Future studies need to collect individual-level SES assessments to more fully address this question.

Provider-level factors

Little attention has been devoted to the role of the provider in the clinical encounter with minority individuals and PAP treatment adherence. In other chronic conditions, discordant patient-provider characteristics (i.e. language, gender, and race-ethnicity) have been associated with lower provider trust and poorer medication adherence [67]. Thus, weaker therapeutic alliances between minority patients and sleep providers may be one factor for lower adherence to PAP, particularly as sleep providers may recommend testing and/or treatment after only a single visit. Other factors which can undermine the patient-provider therapeutic relationship are the provider’s lack of knowledge about cultural health beliefs, communication style, and the misjudgment of the health literacy levels of minority individuals. The former may prevent minority patients from completing hospital-based sleep testing while the latter may result in misunderstanding the risks of OSA, the importance of PAP therapy, and treatment expectations. Finally, provider attitudes and beliefs may also pose barriers to PAP prescription and/or effective counseling on treatment adherence. For instance, aversive racism, negative stereotypes of blacks, may lead white providers to withhold prescribing PAP, to spend less time discussing the therapy, or to provide less follow up with black patients believing that they may be less likely to use it [9]. These provider biases may be implicit or unconscious but have been linked to poorer interpersonal interactions with minority individuals [68]. However, none of these potential provider-level barriers have been examined relative to PAP adherence.

Health care system-level factors

Health care system organization and delivery systems may be a bigger obstacle for minority than white individuals in achieving consistent PAP use. First, insurance coverage may dictate whether a sleep specialist or primary care physician orders a diagnostic sleep study. Minority individuals may have limited access to a sleep specialist evaluation preceding sleep testing, which has been shown to be associated with better PAP adherence [29, 31]. Second, the level of training individuals receive in operating and maintaining PAP may vary widely in the US, with some sleep centers providing extensive education while others rely on durable medical equipment companies that provide variable levels of instruction. Minority individuals may be prone to receive suboptimal training and/or may be more intimidated to ask questions if trained by a culturally-discordant provider. Third, after the initiation of PAP, minority individuals may have more difficulties navigating the health care system to re-engage with sleep providers to address any equipment-related issues/side effects during the critical early period of treatment. Evidence for the latter comes from retrospective studies showing that blacks 1) were less likely to return to clinics for follow up and data card downloads compared to whites and 2) owned PAP for shorter periods of time compared to whites returning to a PAP clinic [18, 42, 69]. Standardizing and streamlining OSA care may help eliminate some of the health care system barriers for minority individuals but to date, there is a near absence of studies that have examined system level barriers and PAP adherence in US minorities.

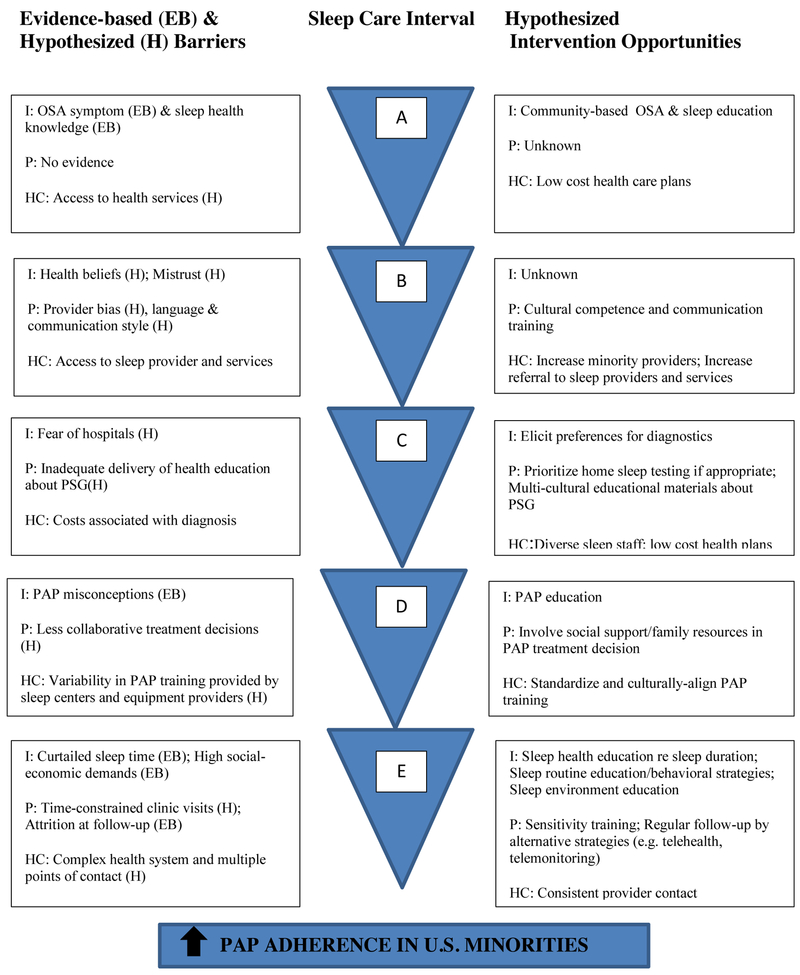

Mechanisms for reducing disparities in PAP use

Other than sleep duration among blacks, other mechanisms which may mediate lower PAP use in US race-ethnic groups are not well understood. However, improvements in PAP adherence among US minorities necessitates not only eliminating the barriers listed above but also testing and potentially tailoring approaches that have been successful in the general OSA populations for US minorities. Strategies shown to increase PAP use among majority OSA samples have implemented one or more of the following: increased education, increased support, behavioral interventions (e.g. motivational enhancement), and use of advanced communication technologies [70]. To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined if these interventions impact PAP adherence differentially by race-ethnicity. Approaches to encourage PAP use in minority individuals includes increasing awareness of the health repercussions of sleep and OSA symptoms and making the sleep study experience less cumbersome and threatening. For example, home sleep studies have been shown to be preferred over in-lab PSGs in an underserved US urban sample [71]. In addition, normalizing PAP treatment by public education in minority communities would also help dispel treatment misconceptions. Improving the living/sleeping environments of minority individuals is a complex issue which would necessitate not only individual level assessments/recommendations but also public housing policy changes. For sleep providers, training in cultural sensitivity and competence (i.e. providing linguistic-, cultural-, and health-literacy appropriate messages about OSA and PAP treatment) and patient-centered communication may achieve several positive effects: 1) promote minority individuals to participate in shared OSA treatment decisions and 2) build trust and strengthen patient-provider relationships [72]. Increasing the diversity of sleep staff and providers to be more representative of community minority individuals may also promote PAP adherence. Finally, providing early and simplified PAP follow up process (e.g. use of wireless modems, telehealth) with immediate feedback to users may be important to empower minority patients to adhere to PAP [73]. These potential interventions implemented across the continuum of sleep care for US minorities are hypothesized opportunities to reduce disparate PAP adherence (Figure 2). Though few trials have addressed such opportunities, a recently completed randomized, controlled trial to address low OSA screening and poor PAP adherence in US blacks by Jean-Louis et al showed that patients randomized to receive culturally and linguistically tailored patient education delivered by a health educator is effective in promoting sleep consultations [74]. Patients randomized to the intervention were three times more likely to undergo an initial sleep consultation compared to those in the attention control group. However, based on subjective reports, there were no differences between the two groups in adherence to PAP. The results suggest that addressing the primary barrier of being screened for OSA could be lessened through culturally and linguistically tailored techniques, but individual, provider and systematic barriers to treatment adherence persist.

Figure 2.

Barriers and testable strategies to improve PAP adherence among US minorities

A=Preceding presentation to health care system; B=OSA assessment by primary care provider or sleep provider; C=Diagnostic testing for OSA; D=Positive airway pressure treatment recommendation and initiation; E=Follow-up care for OSA and positive airway pressure treatment.

Abbreviations- I, individual-level; P, provider-level; HC, health care system-level; EB, evidence-based; H, hypothesized; PAP, positive airway pressure; PSG, polysomnogram.

Limitations

Although our search strategy was extensive, we may have failed to capture all studies which included minority individuals with objective PAP adherence. Studies were only considered if race-ethnicity was a focus of the study and/or the objective PAP adherence of minority individuals was reported and compared to that of whites. Thus, there may be more existing PAP data for US minorities which have not been reported individually.

Conclusion

We provide a comprehensive review of current studies focusing on objective PAP adherence among US minority individuals. We believe this topic will be of increasing importance in coming years given the burgeoning growth of minorities in the US and the greater health care access provided by the Affordable Care Act. Although some data exists for US blacks and Hispanics, there is little to no reported data on PAP use in other US minority groups. We hope that this review stimulates researchers to explore these issues further and determine if or why US minority individuals face challenges with PAP.

Supplementary Material

Research Agenda.

Given the current state of the science revealed in the scoping review of PAP adherence in US minority individuals, the following research recommendations are set forth to address the gaps in the literature:

Increased proportions of minority individuals in larger studies are needed to more precisely estimate differences in adherence to PAP; sampling frames outside of sleep centers are likely to provide estimates consistent with incidence of PAP non-adherence in general minority populations.

Examining barriers to PAP treatment in non-clinical populations with community-based participatory research methods will likely support discovery of unique and important contextual factors relative to OSA and PAP treatment use.

As US race-ethnic groups are heterogenous in terms of their culture, attitudes, beliefs, as well as sleep environments, habits and practices, it is important to examine within- and between-group differences.

Immigrant acculturation to the US lifestyle has been associated with deleterious health behaviors but has not been well studied in PAP use (44).

It is unknown whether cross-cultural training for sleep providers would improve PAP adherence among minority individuals. Addressing such issues could help target interventions involving providers as well as shape future sleep training policies.

Future studies are warranted to understand PAP use differences in US minority sub-groups that are likely at heightened risk for untoward health outcomes associated with OSA; these include minority women, adults with limited healthcare access, and adults with low health literacy.

Practice Points.

US minority individuals may be at higher risk for lower PAP adherence compared to whites.

- During the OSA assessment, providers should consider tailoring treatment recommendations based on minority patients’:

- Health beliefs and attitudes about OSA and PAP

- Health literacy levels

- Social support networks

- Intervention strategies to improve PAP adherence among minority individual may include:

- Community-based educational programs about OSA and PAP

- Provider training about cultural competence and collaborative communication

- Increasing minority representation among sleep providers

- Language- and health-literacy tailored behavioral interventions to PAP

- Use of advanced technologies that are accessible and acceptable to US minorities to monitor and receive feedback on PAP use

Acknowledgments:

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests regarding the project described herein. Dr. Williams was supported by K23HL125939 from NHLBI. Dr. Aloia is a paid employee and stock holder of Philips-Respironics, Inc.

Abbreviations

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- APAP

auto-adjusting positive airway pressure

- ASV

adaptive servo-ventilation

- BMI

body mass index

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PAP

positive airway pressure

- PSG

polysomnography

- SES

socioeconomic status

- TST

total sleep time

- US

United States

- VA

Veterans Administration

Glossary of terms

- Acculturation

multidimensional process of cultural change where a minority group (i.e. immigrants) retains aspects of its culture of origin while adopting practices of a new majority cultural group (i.e. US customs, language, diet)

- Health literacy

the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions

- Self-efficacy

an individual’s confidence in accomplishing a specific task or goal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weiss P, Kryger M. Positive airway pressure therapy for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;16:1331–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antic NA, Catcheside P, Buchan C, Hensley M, Naughton MT, Rowland S, et al. The effect of cpap in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe osa. Sleep. 2011;34:111–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver TE, Sawyer AM. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea: Implications for future interventions. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:245–258 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olaithe M, Bucks RS. Executive dysfunction in osa before and after treatment: A metaanalysis. Sleep. 2013;36:1297–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards C, Mukherjee S, Simpson L, Palmer LJ, Almeida OP, Hillman DR. Depressive symptoms before and after treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in men and women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1029–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Garcia MA, Campos-Rodriguez F, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Catalan-Serra P, Roman-Sanchez P, Montserrat JM. Increased incidence of nonfatal cardiovascular events in stroke patients with sleep apnoea: Effect of cpap treatment. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:906–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawyer AM, Gooneratne NS, Marcus CL, Ofer D, Richards KC, Weaver TE. A systematic review of cpap adherence across age groups: Clinical and empiric insights for developing cpap adherence interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:343–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford MR, Espie CA, Bartlett DJ, Grunstein RR. Integrating psychology and medicine in cpap adherence--new concepts? Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:123–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams NJ, Grandne MA, Snipes A, Rogers A, Williams O, Airhihenbuwa C, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in sleep health and health care: Importance of the sociocultural context. Sleep health. 2015;1:28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods CE, Usher K, Maguire GP. Obstructive sleep apnoea in adult indigenous populations in high-income countries: An integrative review. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiter ME, DeCoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Sleep disorders in african americans and caucasian americans: A meta-analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8:246–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, Loredo J, Hall M, Patel SR, Ramos A, et al. Sleep- disordered breathing in hispanic/latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley KA, Patel SR. Disparities and genetic risk factors in obstructive sleep apnea.Sleep Med. 2016;18:96–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billings ME, Johnson D, Simonelli G, Moore K, Patel SR, Diez Roux AV, et al. Neighborhood walking environment and activity level are associated with obstructive sleep apnea: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Chest. 2016;150:1042–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.*.Budhiraja R, Parthasarathy S, Drake CL, Roth T, Sharief I, Budhiraja P, et al. Early cpap use identifies subsequent adherence to cpap therapy. Sleep. 2007;30:320–324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.*.Joo MJ, Herdegen JJ. Sleep apnea in an urban public hospital: Assessment of severity and treatment adherence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:285–288 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billings ME, Rosen CL, Wang R, Auckley D, Benca R, Foldvary-Schaefer N, et al. Is the relationship between race and continuous positive airway pressure adherence mediated by sleep duration? Sleep. 2013;36:221–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.*.Wallace DM, Shafazand S, Aloia MS, Wohlgemuth WK. The association of age, insomnia, and self-efficacy with continuous positive airway pressure adherence in black, white, and hispanic u.S. Veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:885–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortman JM, Guarneri CE. United states population projections: 2000 to 2050. https://www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf

- 20.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal cpap use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dearholt SL, Dang D. Johns hopkins nursing evidence-based practice model and guidelines (2nd ed). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.*.Billings ME, Auckley D, Benca R, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Iber C, Redline S, et al. Race and residential socioeconomics as predictors of cpap adherence. Sleep. 2011;34:1653–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawyer AM, King TS, Sawyer DA, Rizzo A. Is inconsistent pre-treatment bedtime related to cpap non-adherence? Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:504–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somiah M, Taxin Z, Keating J, Mooney AM, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, et al. Sleep quality, short-term and long-term cpap adherence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:489–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.*.Platt AB, Field SH, Asch DA, Chen Z, Patel NP, Gupta R, et al. Neighborhood of residence is associated with daily adherence to cpap therapy. Sleep. 2009;32:799–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burke TS, Wells ME, Singh J. Domiciliary continuous positive airway pressure therapy in an underserved population: Compliance and influential factors. Pulmonol Respir Res. 2014;2:1 10.7243/2053-6739-7242-7241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*.Pamidi S, Knutson KL, Ghods F, Mokhlesi B. The impact of sleep consultation prior to a diagnostic polysomnogram on continuous positive airway pressure adherence. Chest. 2012;141:51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.*.Guralnick AS, Pant M, Minhaj M, Sweitzer BJ, Mokhlesi B. Cpap adherence in patients with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea prior to elective surgery. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:501–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.*.Balachandran JS, Yu X, Wroblewski K, Mokhlesi B. A brief survey of patients’ first impression after cpap titration predicts future cpap adherence: A pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace DM, Lopez A, Alert M, McNutt M, Chirinos D, Wohlgemuth WK. The influence of race on the trajectory of cpap use during the first 12 weeks of treatment: Standardizing by sleep duration. Sleep. 2015; 38:A180 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye L, Pack AI, Maislin G, Dinges D, Hurley S, McCloskey S, et al. Predictors of continuous positive airway pressure use during the first week of treatment. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:419–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawyer AM, Canamucio A, Moriarty H, Weaver TE, Richards KC, Kuna ST. Do cognitive perceptions influence cpap use? Patient Educ Couns. 2011; 85:85–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colvin LJ, Dace GA, Colvin RM, Ojile J, Collop N. Commercial motor vehicle driver positive airway pressure therapy adherence in a sleep center. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:477–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altememi NA, Assefa S, Riar R, Diaz-Abad M, Scharf SM. Prediction of early cpap compliance. Sleep. 2015;2015:A199–A200 [Google Scholar]

- 37.DelRosso LM, Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr. Continuous positive airway pressure device time to procurement in a disadvantaged population. Sleep disorders. 2015;2015:747906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dudley KA, Fonseca-Lopes S, Seiger AN, Bakker JP, Patel SR. Heterogeneity in predictors of cpap adherence by race. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine: American Thoracic Society International Conference, ATS 2015;191:A2391 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma S, Chakraborty A, Chowdhury A, Mukhtar U, Willes L, Quan SF. Adherence to positive airway pressure therapy in hospitalized patients with decompensated heart failure and sleep-disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:1615–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moran AM, Everhart DE, Davis CE, Wuensch KL, Lee DO, Demaree HA. Personality correlates of adherence with continuous positive airway pressure (cpap). Sleep Breath. 2011;15:687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.*.Means MK, Ulmer CS, Edinger JD. Ethnic differences in continuous positive airway pressure (cpap) adherence in veterans with and without psychiatric disorders. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8:260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.*.Schwartz SW, Sebastiao Y, Rosas J, Iannacone MR, Foulis PR, Anderson WM. Racial disparity in adherence to positive airway pressure among us veterans. Sleep Breath. 2016;20:947–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hale L, Troxel WM, Kravitz HM, Hall MH, Matthews KA. Acculturation and sleep among a multiethnic sample of women: The study of women’s health across the nation (swan). Sleep. 2014;37:309–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace DM, Vargas SS, Schwartz SJ, Aloia MS, Shafazand S. Determinants of continuous positive airway pressure adherence in a sleep clinic cohort of south florida hispanic veterans. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:351–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fulop T, Hickson DA, Wyatt SB, Bhagat R, Rack M, Gowdy O Jr., et al. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms among african-americans in the jackson heart study.Sleep Med. 2012;13:1039–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: A population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, Lutsey PL, Javaheri S, Alcantara C, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa). Sleep. 2015;38:877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AT, US Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw R, McKenzie S, Taylor T, Olafiranye O, Boutin-Foster C, Ogedegbe G, et al. Beliefs and attitudes toward obstructive sleep apnea evaluation and treatment among blacks. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104:510–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Sleep Foundation. 2010 Sleep in America Poll: Summary of findings. 2010

- 51.Wallace DM, Wohlgemuth WK. Does race-ethnicity moderate the relationship between cpap adherence and functional outcomes of sleep in US veterans with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome? J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:1083–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran D, Wallace J. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a publicly funded healthcare system. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:370–374 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawyer AM, King TS, Hanlon A, Richards KC, Sweer L, Rizzo A, et al. Risk assessment for cpap nonadherence in adults with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea: Preliminary testing of the index for nonadherence to pap (i-nap). Sleep Breath. 2014;18:875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez V, Andrade AD, Garcia-Retamero R, Anam R, Rodriguez R, Lisigurski M, et al. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J Health Commun.2013;18 Suppl 1:273–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bakker JP, O’Keefe KM, Neill A, Campbell A Ethnic disparities in cpap compliance in new zealand: Effects of socioeconomic deprivation, health literacy and self-efficacy. Sleep. 2011;34:A0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMenamin TM. A time to work: Recent trends in shift work and flexible schedules. Monthly Labor Review. 2007;3:3–15 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parthasarathy S, Wendel C, Haynes PL, Atwood C, Kuna S. A pilot study of cpap adherence promotion by peer buddies with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:543–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baron KG, Smith TW, Berg CA, Czajkowski LA, Gunn H, Jones CR. Spousal involvement in cpap adherence among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2011;15:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jackson CL, Redline S, Kawachi I, Williams MA, Hu FB. Racial disparities in short sleep duration by occupation and industry. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1442–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams NJ, Grandner MA, Wallace DM, Cuffee Y, Airhihenbuwa C, Okuyemi K, et al. Social and behavioral predictors of insufficient sleep among african americans and caucasians. Sleep Med. 2016;18:103–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slopen N, Lewis TT, Williams DR. Discrimination and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Med. 2016;18:88–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis TT, Troxel WM, Kravitz HM, Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Hall MH. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and sleep in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women. Health Psychol. 2013;32:810–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson CL, Hu FB, Redline S, Williams DR, Mattei J, Kawachi I. Racial/ethnic disparities in short sleep duration by occupation: The contribution of immigrant status. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:71–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: Poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hale L, Do DP. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30:1096–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiter ME, Decoster J, Jacobs L, Lichstein KL. Normal sleep in african-americans and caucasian-americans: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2011;12:209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: Does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1172–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dasgupta N, Desteno D, Williams LA, Hunsinger M. Fanning the flames of prejudice: The influence of specific incidental emotions on implicit prejudice. Emotion. 2009;9:585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Greenberg H, Fleischman J, Gouda HE, De La Cruz AE, Lopez R, Mrejen K, et al. Disparities in obstructive sleep apnea and its management between a minority-serving institution and a voluntary hospital. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wozniak DR, Lasserson TJ, Smith I. Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:1:CD007736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garg N, Rolle AJ, Lee TA, Prasad B. Home-based diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in an urban population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:879–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: Key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuna ST, Shuttleworth D, Chi L, Schutte-Rodin S, Friedman E, Guo H, et al. Web-based access to positive airway pressure usage with or without an initial financial incentive improves treatment use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015;38:1229–1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jean-Louis G, Newsome V, Williams NJ, Zizi F, Ravenell J, Ogedegbe G. Tailored behavioral intervention among blacks with metabolic syndrome and sleep apnea: Results of the metso trial. Sleep. 2016; pii: sp-00150–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.