Abstract

The Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project (Jamkhed CRHP) was established in central India in 1970. The Jamkhed CRHP approach, developed by Rajanikant and Mabelle Arole, was instrumental in influencing the concepts and principles embedded in the 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata.

The Jamkhed CRHP pioneered provision of services close to people’s homes, use of health teams (including community workers), community engagement, integration of services, and promotion of equity, all key elements of the declaration. The extraordinary contributions that the Jamkhed CRHP has made as it approaches its 50th anniversary need to be recognized as the world celebrates the 40th anniversary of the International Conference on Primary Health Care and the writing of the declaration.

We describe the early influence of the Jamkhed CRHP on the declaration as well as the work at Jamkhed, its notable influence in improving the health of the people it has served and continues to serve, the remarkable contributions it has made to training people from around India and the world, and its remarkable influences on programs and policies in India and beyond.

In the early 1970s, leaders of the World Health Organization (WHO) identified a group of projects and programs as implementing a new approach to provision of health care services that was relevant to the realities of developing countries. These projects and programs provided inspiration for the global primary health care movement that began with the first International Conference on Primary Health Care at Alma-Ata (now referred to as Almaty), Kazakhstan, in 1978 and its Declaration of Alma-Ata.1 In 1975 WHO published Health by the People,2 containing 10 case studies illustrating these new approaches. Perhaps foremost among these programs—at least in terms of its influence on the ideas and concepts embedded in the Alma-Ata Declaration itself—was the Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project3 (Jamkhed CRHP), established in rural central India in the state of Maharashtra by Rajanikant and Mabelle Arole almost a half century ago (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Mabelle and Rajanikant Arole: 1994

Source. Arole and Arole (back cover).5 Printed with permission.

The Aroles were actively engaged with the Christian Medical Commission of the World Council of Churches, which in the late 1960s had begun to critically examine the relevance of Christian medical mission programs. Up to that point, Christian medical missions had focused on curative hospital care with little attention to prevention and extension of primary health care to the village level. The work of this commission caught the attention of Kenneth Newell, who at that time was the director of WHO’s Division of Strengthening Health Services, and other leaders at WHO including Halfdan Mahler, who became director general in 1973. A history4 of the committee’s influence on the development of WHO’s primary health care approach highlights the particular importance of the Jamkhed CRHP. We have personal knowledge of the history and contributions of the Jamkhed CRHP through our visits to Jamkhed since the 1970s, through our friendships with the Aroles, and through the training offered to the project’s students.

As part of the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Declaration of Alma-Ata, we highlight some of the Jamkhed CRHP’s remarkable pioneering contributions to the principles and practice of primary health care and to the movement locally, regionally, nationally, and globally.

A HALF CENTURY OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

In 1970, the Aroles gained the confidence and trust of the local people in a poor, arid agricultural region of India called Jamkhed, initially by providing them with medical care, listening to their needs and aspirations, responding to them as they were able, and thereby building true partnerships. Recognizing that poor health was related to lack of clean water, discrimination against lower castes, ignorance of principles of hygiene and nutrition, and marginal farming conditions, the Aroles embarked on a comprehensive economic and social approach to improving health. They taught illiterate women (who were mostly widows or outcastes) to provide health education, improve child feeding practices, and provide simple curative care. They placed hand pumps in low-caste areas, guided farmers to impound runoff rainwater, offered adult literacy classes, taught hygiene and nutrition, and led the village people in many other activities.

The work spread gradually to 30 villages and, by 1985, to 250 villages with a population of more than 250 000 people. This expansion took place with minimal additional staff and budgets, largely carried out by villagers and community health workers (CHWs) who were eager to share what they had learned and experienced. The mobile team from the Jamkhed CRHP facilitated this expansion, which became a people’s movement for health.

In 1990 the Jamkhed-area villagers, on their own initiative, bought bus tickets and traveled to Bhandardara, 250 kilometers away, to teach and support volunteer community workers in their efforts to make space for a new dam; these community workers were recruited from a group of 60 000 tribal people who had been displaced from their native forest heritage. In another area, Latur, four hours from Jamkhed, an earthquake killed 30 000 people in 1993. The CHWs and villagers of Jamkhed and Bhandardara rushed there to offer their assistance, and then, at the request of the people of Latur, the CHWs helped develop a program similar to Jamkhed’s. These activities eventually reached a population of more than 500 000 people.

The Jamkhed CRHP was one of the first programs to demonstrate the effectiveness of illiterate female CHWs. In 1970, when the Jamkhed CRHP began, levels of ill health and poverty in the area were among the worst in the world. The infant mortality rate was 176 per 1000 live births, 40% of children younger than five years were malnourished, and coverage rates for family planning, prenatal care, and birth attendance by a trained provider were all less than 1%.5 It was not uncommon for women to be treated as property without personal rights. One third of the population was migrating to sugar cane plantations to work in temporary jobs because no food or work was available in Jamkhed. The area was experiencing a severe drought, and the population faced near-starvation conditions.

Within five years, the infant mortality rate fell to 52 per 1000 live births, antenatal care coverage increased to 80%, 74% of deliveries were conducted by trained personnel in hygienic conditions, the percentage of children who were fully immunized increased from 1% to 81%, and leprosy prevalence dropped by half. After 20 years, in 1990, the infant mortality rate was 26 per 1000 live births, 60% of eligible couples were using family planning, fewer than 5% of children were malnourished, and the prevalence of tuberculosis had fallen by two thirds. Neonatal tetanus disappeared as a result of maternal immunizations and sterile umbilical cord care.5 The hospital was initially full of children with dehydration from diarrhea, pneumonia, and severe malnutrition. Today, the hospital inpatient census is much lower, and most patients are adults.

Currently, 100% of pregnant women receive antenatal care and have safe deliveries, and fewer than 1% of children are malnourished. According to statistics still maintained and scrutinized by communities in the area, the infant mortality rate is now 15 deaths per 1000 live births, and the maternal mortality ratio is less than 100 per 100 000 live births.6 These levels represent about half the mortality of similar populations in rural Maharashtra.7

An independent external evaluation published in 2010 showed that, during the period from 1992 until 2007, mortality in the 1- to 59-month age group was 30% less in the Jamkhed service area than in a surrounding set of comparison villages.8 The results would have been much more striking had the evaluation been conducted earlier, during the rapid decline in infant mortality in the 1970s. A recent comprehensive review of the effectiveness of community-based primary health care identified only four programs worldwide with strong evidence of mortality impact among children younger than 5 years after a period of at least 10 years.9 One of these programs was the Jamkhed CRHP.

Since 1970, almost 10 000 tuberculosis patients in Jamkhed have been identified and successfully treated, as have more than 5000 patients with leprosy. Part of the treatment involved integrating these patients back into the life of their communities. A comparative study showed a much lower level of social stigma associated with leprosy in Jamkhed CRHP villages than in villages in other areas.10 With common maternal, child, and infectious health problems under control, other health and development problems are now being addressed by the communities, including noncommunicable diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, mental illness), adolescent health, and health problems among the elderly.

Three tiers of work have evolved at the Jamkhed CRHP. At the community level (the first tier), 200 CHWs in 150 Jamkhed-area villages (approximately one CHW per 1000 population) provide education, health care (both preventive and curative), and leadership to community groups. Farmers’ clubs and women’s groups are organized around their own interests, and they assist CHWs in village work. As communities learn and gain confidence in their abilities, they do more in identifying health problems, analyzing causes, setting priorities, and developing local solutions with local resources.

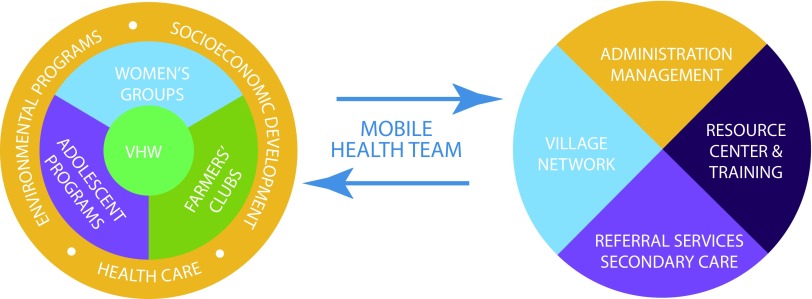

In second-tier work, a mobile team composed of a nurse, a paramedic, and a social worker visits each village periodically to provide support and assistance. The mobile team sees patients referred by the CHWs, acutely ill patients, those recently discharged from the hospital, and pregnant and newly delivered women. The team also visits people with chronic conditions and talks with village leaders about current issues. In addition, they support the CHWs with new information and facilitate problem solving, both at the time of their community visit and when the CHWs travel to Jamkhed for in-service training. The third tier consists of hospital and outpatient clinic services available in Jamkhed, where there are also central offices, a hostel for trainees, and classrooms. Figure 2 provides an overview of the community programs and their links to the services available in Jamkhed.

FIGURE 2—

Diagram of the Key Components of the Comprehensive Primary Health Care Program in Jamkhed, India

Note. VHW = village health workers, a term used interchangeably with community health workers.

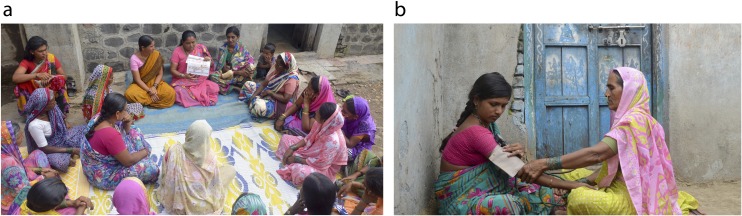

The key change agent is the CHW, selected by the community (Figures 3 and 4). She receives training in health, community development, communication, and personal development. At the outset, many of these CHWs were illiterate, drawn from the “untouchable” (dalit) castes. The primary responsibilities of the CHWs are to share their knowledge with everyone in the community, provide basic health care, organize groups, and offer special support to the poorest and marginalized members. Although the CHWs are volunteers, they are taught skills that help them earn their own living through microenterprise.

FIGURE 3—

The Community Health Workers of the Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project: Jamkhed, India

Source. Photo courtesy of Alexis Barab. Printed with permission.

FIGURE 4—

Community Health Workers (a) Leading a Women’s Group Meeting and (b) Monitoring the Blood Pressure During a Home Visit

Source. Photos courtesy of Alexis Barab. Printed with permission.

Once each week, the CHWs visit the central training facility in Jamkhed, where they stay overnight, learn from one another and from the mobile health team, enjoy group activities, and provide each other with social support. Most of these women have been CHWs for several decades now, and dropouts have been exceptionally rare.

The CHWs maintain a simple health information system in each village. They record births and deaths, family planning usage, and child immunizations, along with other basic information (including information from other sectors such as agriculture and the environment), often using indicators chosen by the villagers themselves. They place a summary of these statistics on a blackboard in the center of each village where everyone can readily review the situation, discuss the problems identified, and assess the progress being made.

Rather than creating duplicate services and programs, the Jamkhed CRHP links villages and their needs with available resources in governmental and nongovernmental programs. Government programs provide immunizations and family planning services. Lawyers volunteer their time to talk with village women to orient them about their legal rights, and government officials talk with villagers about how to apply for government loans and participate in other government support programs, especially in improved agriculture and small business.

The Jamkhed CRHP has a demonstration and training farm where it promotes new crops appropriate to local conditions, new farming techniques (including organic methods), animal husbandry, and new income-generating activities. More than 4200 people (mostly women) have improved their incomes as a result of this training and have enhanced the nutrition of their families and communities. The farm also provides a livelihood as well as a home for destitute women with chronic illnesses such as HIV/AIDS and for women who are victims of domestic violence, giving them dignity and hope.

The Jamkhed CRHP has, from the beginning, addressed broad community concerns and the needs of the whole person rather than simply providing narrowly focused curative and preventive health services. It has addressed the social determinants of health, such as the low status of women, the caste system, and poverty. Farmers’ clubs have planted millions of trees, improved the land for agricultural production and watershed development, and learned to use appropriate technology such as bio-gas and vermiculture. CHWs have learned about herbal medicines and home remedies, including homemade oral rehydration therapy and steam inhalation. A small team of local villagers received training in fitting artificial limbs (e.g., the “Jaipur foot”) and has helped more than 25 000 amputees throughout the state of Maharashtra. This team has trained other groups to produce and fit the “Jaipur foot” for landmine victims in Angola, Liberia, and Mozambique.

Increasingly, the Jamkhed CRHP has placed an emphasis on women’s empowerment and elevation of self-esteem, especially among girls, and the program has established a cooperative bank for women. Currently, there are more than 200 women’s self-help groups with 3000 members in project villages. These groups have initiated savings and loan programs and activities directed at reducing domestic violence and alcoholism. Adolescent groups have been present now for 20 years in 30 villages. These groups promote health education, self-confidence, creative expression, and deferral of marriage and pregnancy to older ages. Girls finish formal schooling and even learn karate to improve their self-defense skills and enhance their self-esteem.

Through this comprehensive approach, the Jamkhed CRHP proudly proclaimed its achievement of all of the Millennium Development Goals far ahead of the 2015 target, not only goals related to health but also those involving eradication of extreme poverty and hunger, achievement of universal primary education, promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment, and assurance of environmental sustainability (including universal access to safe drinking water and sanitation).

The Jamkhed CRHP has now been operating for 49 years, a tribute to the long-term commitment and remarkable leadership of Rajanikant and Mabelle Arole and their two children Shobha and Ravi, who have led the organization since the death of their parents. Their outstanding leadership and the Jamkhed CRHP’s very low operational costs, most of which (aside from training costs) are generated locally, have ensured the program’s sustainability.

The Jamkhed CRHP works with communities to ensure that poor and marginalized people achieve an acceptable level of health; it does so using the principles of primary health care, as defined at Alma-Ata in 1978. The program has demonstrated long-term success in addressing all three pillars of the Declaration of Alma-Ata: equity, community participation, and intersectoral collaboration. In terms of equity, low-caste women, widows, and marginalized groups have received priority in programming. In terms of community participation, community engagement and community empowerment are at the heart of all activities. In terms of intersectoral collaboration, addressing the social determinants of health, such as poverty, gender disparity, and caste barriers, has been a constant priority. These achievements have been possible through empowerment of communities, building their capacity to solve their own problems and carry out work themselves.

THE JAMKHED INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE

The Jamkhed International Institute for Training and Research in Community Health and Population has provided training for 45 000 individuals, 42 000 from throughout India and 3000 from more than 100 other countries. They include grassroots workers, project managers, doctors, nurses, government workers, administrators, and medical and public health students. Field studies and publications cover a broad range of primary health care topics.8,11–17 The book written by the Aroles about their experience in establishing the Jamkhed CRHP5 has become a global health classic, and descriptions of the program and its renowned CHWs have been published as well.18–20 The Institute has had long-term relationships with numerous organizations such as the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Maastricht School of Medicine in the Netherlands, the Nossal Institute for Global Health at the University of Melbourne’s School of Population and Global Health, and the United Methodist Church.

MOVING FROM LOCAL SUCCESS TO GLOBAL INFLUENCE

The Jamkhed CRHP was influential in the lead up to the International Conference on Primary Health Care at Alma-Ata in 1978, having shown early on what is possible through adherence to the principles of community involvement in health and development. It has since become a premier example of the achievement of health for all through accessible and affordable primary health care in partnership with communities; through assignment of priority to mothers, children, and the poor; through women’s empowerment; and through intersectoral approaches that address the social determinants of health.

Furthermore, the renown of the Jamkhed CRHP and its CHWs led the government of India to create the world’s second large-scale CHW program in 1977 (China was the first to develop such a program). The government provided three months of training for 500 000 CHWs (called village health guides) in rural villages. Unfortunately, this program failed because of poor selection of CHWs (often chosen by headmen from relatives or friends) and a lack of supportive supervisory and logistical support, critical elements of the Jamkhed approach.21,22 Government planners attempted to copy only the training component and ignored the crucial aspects of community engagement and ongoing posttraining support.

This was a major setback for the community health movement in India and beyond. However, the more recent CHW national system in India, introduced in 2005, consists of almost 1 million accredited social health activists, all women. This program was also heavily influenced by the Jamkhed CRHP experience and is much better integrated into the national rural health system. In the 1990s, Mabelle Arole served as the Advisor, Health and Nutrition of the UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) Regional Office for South Asia, based in Kathmandu. From that platform, she was able to spread the Jamkhed model widely.

At the Global Health Council’s annual meeting in 1988 in Washington, DC, Muktabai Pol, a CHW from Jamkhed, shared her experiences in providing primary health care in a remote village. She concluded her speech by lighting a small wick lamp and saying “I am like this lamp, lighting the lamp of better health. Workers like me can light another and another and thus encircle the whole earth. This is ‘health for all.’ ”5(p1) The Jamkhed CRHP, its leaders, CHWs, and villagers have lit a lamp that is still burning and provides a vision of how health for all can be achieved through primary health care.

CONCLUSION

As the world celebrates the 40th anniversary of the International Conference on Primary Health Care and the Declaration of Alma-Ata, it is also an opportune moment to recognize and celebrate the Jamkhed CRHP’s seminal influence over the past half century on the emergence of CHWs and comprehensive community-based primary health care, women’s empowerment, intersectoral collaboration, and community engagement as vital forces in achieving universal health coverage, ending preventable child and maternal deaths, and, eventually, achieving health for all through primary health care as envisioned at Alma-Ata in 1978.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Shobha Arole and Ravi Arole, directors of the Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project, and Connie Gates, director of Jamkhed International/North America, provided valuable comments on earlier versions of this commentary.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Neither author reports any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Available at: http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 2.Newell KW. Health by the People. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project. Jamkhed CRHP home page. Available at: http://jamkhed.org. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 4.Litsios S. The Christian Medical Commission and the development of the World Health Organization’s primary health care approach. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1884–1893. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arole M, Arole R. Jamkhed—A Comprehensive Rural Health Project. London, England: Macmillan; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamkhed Comprehensive Rural Health Project. Comprehensive Rural Health Project impact. Available at: http://jamkhed.org/jamkhed-impact. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 7.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Maharashtra: National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005–06. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann V, Eble A, Frost C, Premkumar R, Boone P. Retrospective comparative evaluation of the lasting impact of a community-based primary health care programme on under-5 mortality in villages around Jamkhed, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(10):727–736. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry HB, Rassekh BM, Gupta S, Freeman PA. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 7. Shared characteristics of projects with evidence of long-term mortality impact. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):010907. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arole S, Premkumar R, Arole R, Maury M, Saunderson P. Social stigma: a comparative qualitative study of integrated and vertical care approaches to leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73(2):186–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arole S, Premkumar R, Arole R, Mehendale S, Risbud A, Paranjape R. Prevalence of HIV infection in pregnant women in remote rural areas of Maharastra State, India. Trop Doct. 2005;35(2):111–112. doi: 10.1258/0049475054037110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Premkumar R, Pothen J, Rima J, Arole S. Prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension in a community-based primary health care program villages at central India. Indian Heart J. 2016;68(3):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCord C, Premkumar R, Arole S, Arole R. Efficient and effective emergency obstetric care in a rural Indian community where most deliveries are at home. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75(3):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Joag K, Jorm AF. Community beliefs about causes and risks for mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(6):606–622. doi: 10.1177/0020764009345058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Joag K, Jorm AF. Community beliefs about treatments and outcomes of mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Public Health. 2009;123(7):476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Pathare S, Jorm AF. Attitudes to people with mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(12):1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kermode M, Herrman H, Arole R, White J, Premkumar R, Patel V. Empowerment of women and mental health promotion: a qualitative study in rural Maharashtra, India. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arole M. The Comprehensive Rural Health Project in Jamkhed, India. In: Rohde JE, Wyon J, editors. Community-Based Health Care: Lessons from Bangladesh to Boston. Boston, MA: Management Sciences for Health; 2002. pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arole M, Arole R. Jamkhed, India: the evolution of a world training center. In: Taylor-Ide D, Taylor C, editors. Just and Lasting Change: When Communities Own Their Futures. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. pp. 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg T. Necessary angels. Natl Geogr Mag. December 2008:70–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry H, Scott K, Javadi D Case studies of large-scale community health worker programs: examples from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, Niger, Pakistan, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Available at: https://www.mcsprogram.org/resource/case-studies-large-scale-community-health-worker-programs-2/?_sfm_resource_topic=community-health. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 22.Banerji D. Politics of rural health in India. Int J Health Serv. 2005;35(4):783–796. doi: 10.2190/1G7Y-KVE3-B6YV-ANE9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]