State and local health departments continue to report extensive workforce shortages, even though the number of schools and programs of public health has increased and produced 69% more graduates in 2011 compared with 2001.1 Theoretically, these newly trained public health graduates would fill vacancies and shortages; however, data indicate that the vast majority do not take jobs in governmental public health.1 Leaders in public health agencies perceive that salaries are a barrier to recruiting new employees and indicate that salary gaps contribute to workforce shortages for epidemiologists, laboratory scientists, nurses, and environmental health workers.2 However, are low salaries really the barrier for public health hiring?

SALARY AND SATISFACTION

On the one hand, some data indicate that salary might not be the issue. The 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS) provided employees’ perceptions about salaries in governmental public health agencies, and the picture did not appear as grim as had been speculated.3 Other studies have reported that salary was not a strong predictor of intention to leave a governmental public health agency and was less influential than job satisfaction in terms of voluntary departures.4

Overall, public health employees are collectively more satisfied with their salaries than are other US workers (50% among state and local governmental public health employees compared with national reports of 45%).5,6 The Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests that salaries in governmental public health occupations are more competitive than in the private sector and other industries nationally (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). For example, the median yearly public health salary ranges between $45 000 and $55 000, whereas the median salary for all fields and sectors is $37 690 nationally. Furthermore, data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/oes) and other federal government organizations also indicate that public health occupations historically viewed as sensitive to salary competition are equivalent to those in the public and private sectors when aggregated nationally (Figure A).

On the other hand, some salary-related differences do exist. As shown by Sellers et al. (p. 674) in this issue of AJPH, state health agency employees earn higher salaries than do those in local public health, but big city health department employees have salaries similar to their counterparts in state health agencies. Although the higher cost of living in large cities and increased market competition for public health employees might account for higher salaries in big city health departments,3 PH WINS data indicate that employees with a master’s degree earn more at the state level (median = $55 000–$65 000/year) than at a local health department not in a big city (median = $45 000-$55 000/year) (Figure A). Salary differences observed among men and women doing the same job are less prominent in public health than national averages, with women earning $0.90 to $0.95 on the dollar compared with men in the former and $0.78 on the dollar in the latter.3

INTRASTATE SALARY VARIATION MATTERS

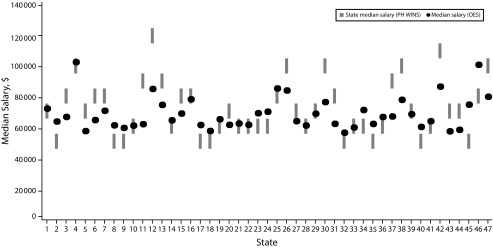

Although salaries look similar when aggregated nationally, review of state-by-state data shows variabilities that might account for the disconnect between the national findings and views from public health leaders. For example, Figure 1 shows interstate and intrastate variability in salaries reported for nurses across all sectors, compared with nurses employed at state health agencies who participated in PH WINS. A similar chart showing salary variability for epidemiologists is presented in Figure B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Numerous states have a $15 000 or greater salary gap between state health agency employees and that state’s average for that occupation across all sectors. In essence, nationally aggregated salary data may cover up some of the salary gaps that public health leaders report as challenging for recruitment and retention.

FIGURE 1—

State Variation in Median Salary for Registered Nurses, Compared With State Health Agency Central Office, 2017

Note. OES = occupational employment statistics; PH WINS = 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. The x-axis represents states and corresponding SHA that participated in PH WINS. All states participated except Colorado, New Jersey, and Oregon. States rearranged and numbered 1–47 to protect confidentiality of SHAs.

Source. PH WINS 20173 for state health agency central office median salary range. Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://www.bls.gov/oes) for state median salary, all sectors; includes all governmental employees in the noted occupation.

Data suggest that salary gaps between local, state, and private-sector employees are a particular challenge for certain occupations, and we anticipate that certain public health positions related to informatics, data analytics, nursing, and epidemiology will continue to encounter substantial competition from the private sector. But what can a public health agency reasonably be expected to do to address within-state salary discrepancies during times of significant austerity and impending retirements?

FINDING SOLUTIONS

In places where salary gaps are a factor, public health officials can assess the feasibility of certain salary-centered approaches. One option is to consider salary bands in states with flexibility to increase salaries. An agency can target specific key occupations and implement widened salary bands to be more competitive with the private sector. A second option is to identify nonmonetary mechanisms to incentivize recruitment and retention for those positions, including improving the marketing of the position specifically and of public health careers more generally, increasing support for professional development, and establishing clear paths for career advancement within the agency.1

Another option is to use task shifting to make the finite amount of funding that agencies have for salaries go farther. During the past decades, the private sector has pushed all types of clinicians to work at the apex of their clinical abilities and delegate nonclinical tasks to staff without the same level of skill or technical training. Given the shift away from direct services in public health, especially at the state level, public health agencies can review duties to determine what work could be shifted to less skilled positions, and the saved funding could be used to sufficiently fund positions requiring higher skills and salaries. Although it would be a substantial undertaking, states might consider reexamining public health statutes that require certain types of nonclinical activities to be provided by nurses and other clinical providers. For instance, PH WINS data show that approximately 40% of the employees with a nursing degree at the state health agency level work outside clinical settings, and at the local level, 21% of nurses hold roles that are nonclinical. Defining these roles appropriately is critical, especially for public health nursing, as Bekemeier et al.7(p50) note, “the inefficient or improper deployment of the limited public health nursing workforce can adversely undermine the health of whole populations.”

Consideration of the different levels of analytic and training requirements is necessary to fill different kinds of roles and programs. Although many consider a master of public health (MPH) degree a standard for entry into the field, some lower-level positions could be staffed by trained public health workers with bachelor’s degrees. Doing so would allow public health agencies to concentrate scarce salary dollars into a smaller number of MPH-required positions and have those positions conduct the more sophisticated tasks that truly require the higher level of formal training that comes with a master’s degree. This could be a financially viable alternative for cash-strapped agencies to attract qualified MPH graduates into governmental public health by raising job requirements and salary levels for these roles.

Although salaries are not the only barrier to public health hiring, state and local health departments should engage in discussions regarding how the public health workforce perceive salary and benefits.7 Even though benefits packages in public sector jobs have been considerably weakened in recent years, they are still viewed as a competitive advantage compared with benefits in private sector jobs.3 In addition, exploring strategies to implement in states where the funding and authority exist to maneuver salary bands should be considered. As the field of governmental public health remains poised for generational change, state and local governmental public health can and should do more to recruit and retain the best and the brightest. Salary discussions are only one important part of these efforts, but the likelihood exists that only better financial compensation and incentives will help recruitment and retention, especially for key public health occupations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Fátima Coronado, MD, MPH, for her contributions to and support of this work.

The 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey was conducted as a collaboration between the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the de Beaumont Foundation. Jonathon P. Leider was a consultant to the project.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Sellers et al., p. 674.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leider JP, Harper E, Bharthapudi K, Castrucci BC. Educational attainment of the public health workforce and its implications for workforce development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S56–S68. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck AJ, Leider JP, Coronado F, Harper E. State health agency and local health department workforce: identifying top development needs. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1418–1424. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sellers K, Leider JP, Bogaert K, Allen JD, Castrucci BC. Making a living in governmental public health: variation in earnings by employee characteristics and work setting. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2) doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000935. Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey 2017):S87–S95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liss-Levinson R, Bharthapudi K, Leider JP, Sellers K. Loving and leaving public health: predictors of intentions to quit among state health agency workers. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S91–S101. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monster Worldwide Despite being unhappy with their pay, nearly 8 in 10 find great satisfaction with the people they work with, according to Monster’s Global Wage Index ReportDecember 112014Available at: https://www.monster.com/about/a/workers-unhappy-with-pay-happy-with-coworkers-survey-says-1211. Accessed September 24, 2017

- 6.Sellers K, Leider JP, Harper E et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey: the first national survey of state agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S13–S27. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekemeier B, Walker Linderman T, Kneipp S, Zahner SJ. Updating the definition and role of public health nursing to advance and guide the specialty. Public Health Nurs. 2015;32(1):50–57. doi: 10.1111/phn.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]