Abstract

Objectives. To describe policies related to parental leave, breastfeeding, and childcare for faculty and staff at top schools of public health in the United States.

Methods. We identified the top 25 schools of public health from the US News and World Report rankings. We reviewed each institutional Web site to identify publicly available policies as of July 2018.

Results. For birth mothers, 80% (20/25) of the schools provided paid childbearing leave to faculty (mean = 8.2 weeks), and 48% (12/25) provided paid childbearing leave for staff (mean = 5.0 weeks). For nonbirth parents, 68% (17/25) provided paid parental leave for faculty and 52% (13/25) for staff (range = 1–15 weeks). We found that 64% (16/25) of the schools had publicly available lactation policies, and 72% (18/25) of the schools had at least 1 university-run on-campus childcare center.

Conclusions. The majority of top US schools of public health provide paid leave to faculty birth mothers. However, most schools fall short of the 14 weeks recommended by the American Public Health Association.

The public health community has long recognized that dedicated time for parents to be with their child in the earliest months of life offers significant benefits for both infant and maternal health.1 Reflecting this commitment, the American Public Health Association (APHA) recommends at least 14 weeks of paid maternity leave.2 Workplace policies in the United States, however, are often poorly aligned with the needs of infants and their families. For example, in a worldwide survey of 185 countries, the United States is 1 of only 2 countries that does not guarantee paid maternity leave.3 Globally, among the other countries, the average duration of paid maternity leave is between 14 and 17 weeks, as compared with less than 4 weeks for US women.4 The United States’ lack of paid maternity leave has been linked to a range of health consequences for infants and new mothers, including lower rates of breastfeeding and childhood immunizations, along with higher rates of child mortality and maternal depression.5,6

Historically, employment leave for new parents, when available, has typically focused on birth mothers. Yet an accumulating body of evidence suggests that leave for nonbirth parents also has substantial public health impacts. For example, paternity leave is associated with increased rates of breastfeeding, as well as various emotional, psychological, behavioral, and cognitive benefits for children.1 Paternity leave may also have a positive effect on the return of mothers to the workplace and potentially mitigate workplace discrimination against women.1 Therefore, parental leave, understood as some form of legal or institutional guarantee that a new parent can take time off to be with their child, is supported by several justifications.

Other workplace policies related to childbirth and childcare also have additional public health implications. For example, the public health community has a longstanding commitment to breastfeeding, given its association with a wide-ranging list of benefits for both infants and breastfeeding mothers. For infants, breastfeeding is associated with reduced risk of acute otitis media, gastrointestinal infections, respiratory infections, sudden infant death syndrome, and, for preterm infants, necrotizing enterocolitis.7 For mothers, lactation has been associated with reduced risks of some types of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer,8–10 and may also play a critical role in women’s recovery from pregnancy and their long-term metabolic health.11,12 However, numerous studies suggest that workplace policies, including insufficient accommodations for and support of nursing mothers, may undermine women’s ability to successfully combine breastfeeding and full-time employment.13

Health professions have an influential role in modeling policies that support the needs of infants and their families. Yet previous studies have documented gaps between the expressed policy statements of health societies and the actual policies operating within individual health institutions. For example, The APHA, along with numerous clinical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommends that infants be exclusively fed breast milk for the first 6 months of life and that breastfeeding continue to at least 1 year of age.2,14–16 Policies within medical schools17 and among both obstetrics and gynecology residency training programs and academic surgeons, however, often fail to align with these expressed ideals.18,19

For example, a lack of paid maternity leave may undermine the likelihood that women meet recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding and, as the APHA itself has argued, may perpetuate inequities among lower-income women, who cannot afford to take unpaid time off.20 A recent study of family and childbearing leave policies at top US medical schools found the mean length of full salary support during childbearing leave was 8.6 weeks—well short of either the 12 weeks endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics or the 14 weeks recommended by the APHA to support breastfeeding and the overall health of new mothers and their infants.2,21 As anecdotal reports from observations of our own colleagues that suggest similar policy shortcomings exist in schools of public health, we examined policies related to family leave, breastfeeding (including workplace accommodations for lactating mothers), and childcare resources for both faculty and staff at top schools of public health.

METHODS

We identified the top ranked schools of public health by using the 2015 US News and World Report. One of 2 authors (L. S. and M. M.) reviewed each institutional Web site to identify the most current publicly available policy regarding parental leave and breastfeeding as of July 2018 for both faculty and staff. To confirm consistency in coding, we double-coded 36% of faculty policies. We resolved any discrepancies through discussion. We defined “paid childbearing leave” as protected leave with at least some salary for birth mothers, without the mandated use of sick, vacation, or other accrued personal time (see the box on this page). We defined “paid parental leave” as protected leave with at least some salary for nonbirth parents, including fathers, same-sex couples, and adoptive parents. We defined “paid medical leave” as leave funded through extended sick or disability leave (not accrued sick leave). We defined “unpaid” leave, whether for childbearing or nonbirth parents, as protected leave intended for care of a new child without dedicated salary coverage, including use of accrued sick or vacation time. Schools that indicated that faculty or staff could “request” leave, but stated that the decision to grant leave would be up to the individual supervisor or other official, were categorized as having no protected leave.

Leave Types for Birth Mothers and Nonbirth Parents.

| Paid childbearing leave |

| • At least some salary provided |

| • Protected; not at discretion of a supervisor or chair |

| • Length of leave set by university |

| • Does not require use of accrued sick days, vacation, etc. |

| Paid medical leave |

| • At least some salary |

| • Protected; not at discretion of a supervisor or chair |

| • Length of leave at the discretion of birth mother’s physician, with a maximum length set by the university |

| • Leave may be taken out of accrued disability leave, depending on the university’s policy |

| Unpaid leave |

| • Protected; not at discretion of a supervisor or chair |

| • Unpaid, unless various accrued time is used |

| • Length of leave is generally a maximum set by the university or the birth mother’s physician, depending on the university’s policy |

To confirm accurate interpretation of each school’s policy, we contacted faculty affairs and human resources departments at each school by phone or e-mail.

RESULTS

All 25 schools provided publicly available data on their institutional parental leave policies for both faculty and staff; 16 provided publicly available lactation policies (including workplace accommodations and resources for lactating mothers), and 24 provided information related to childcare resources. We successfully contacted 20 schools via telephone or e-mail to confirm their policies for staff, and 18 to confirm those for faculty. However, at several schools (approximately 10), we encountered challenges in identifying the appropriate institutional contact. For example, one institution’s human resources department informed us that the relevant policies were under the jurisdiction of the provost’s office, only to have the provost’s office state that they were the responsibility of the human resources department. Furthermore, policies for faculty and for staff were often under the direction of different administrative departments within the university.

Faculty Policies

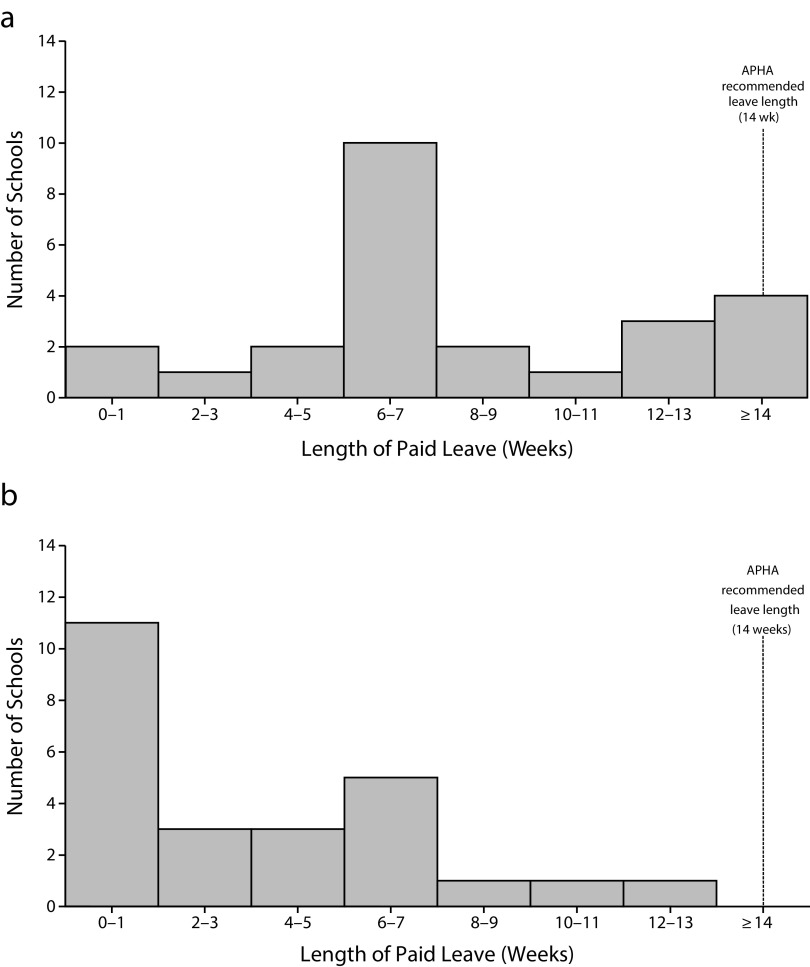

For 3 schools (Harvard, Columbia, and Yale), policies specific to the school of public health were more generous than university-wide policies; the remaining 22 schools of public health applied university-wide policies to family leave. For birth mothers, 22 schools (88%) provided some form of paid leave (Table 1). Twenty provided paid childbearing leave (80%), with a mean length of 8.2 weeks (Figure 1; range = 2–15 weeks). Of those 20, 3 provided at least 14 weeks of paid leave, consistent with APHA recommendations. Four provided paid medical leave that can be used for childbirth. Of those 4, 1 provided between 6 and 8 weeks, while 3 relied on direction from the individual faculty member’s clinician. Two schools offered both paid childbearing and paid medical leave. Ten institutions offered unpaid leave time, with a range of 6 weeks to 1 year. Nine schools offered both paid and unpaid protected leave for faculty birth mothers.

TABLE 1—

Faculty Leave Policies at Top Schools of Public Health in the United States: July 2018

| Birth Mother |

Nonbirth Parent |

||||

| University | Paid Childbearing | Paid Medical | Unpaid Maternitya (Beyond FMLAb) | Paid Parental | Unpaid Parentala (Beyond FMLAb) |

| Boston University | 6 wk | ||||

| Columbia Universityc | 13 wk | 13 wk | |||

| Drexel University | 6 wk4 | 6 wkd,e | |||

| Emory University | 1 semesterf | max 6 mog | 1 semesterf | ||

| George Washington University | 15 wk | 15 wk | |||

| Harvard Universityc | 13 wk | 13 wk | |||

| Johns Hopkins University | 10 wk | 4 wk | |||

| Ohio State University | 6 wk | 6 wk | 3 wk | ||

| St Louis University | 6 wk | ||||

| Tulane University | 6 wk | 1 semester | 6 wk | 1 semester | |

| University of Alabama - Birmingham | 4 wk | 4 wk | |||

| University of California - Berkeley | 6 wk | 1 y | 1 y | ||

| University of California - Los Angeles | 6 wk | 1 y | 1 y | ||

| University of Illinois - Chicago | 2 wk | 2 wk | |||

| University of Iowa | 6 wk | 1 wke | |||

| University of Maryland - College Park | 8 wk | 8 wk | |||

| University of Michigan - Ann Arbor | 6–8 wkg | 1 y | 1 y | ||

| University of Minnesota - Twin Cities | 6 wk | 6 wk | |||

| University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill | 15 wk | 15 wk | |||

| University of Pittsburgh | 4 wk | 6–8 wk, max 26g | 1 y | 4 wk | 1 y |

| University of South Carolina | 6 wke | ||||

| University of South Florida | 15 wk | 6 mo | 15 wk | 6 mo | |

| University of Texas Houston Health Sciences | |||||

| University of Washington | Max 90 dg | 6 mo | 6 mo | ||

| Yale Universityc | 8 wk | 4 mo | 8 wk | 4 mo | |

Note. FMLA = Family Medical Leave Act (Pub L No. 103-3 [1993]).

Accrued personal time can be used to receive pay.

FMLA requires employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for qualified family and medical reasons to employees.

School of public health–specific policy.

Depends on time at the university.

Only for new adoptive parents.

Only a leave from teaching duties; still expected to continue departmental services and research.

Length is at the discretion of the mother’s physician.

FIGURE 1—

Distribution of Paid Leave Length at Top US Schools of Public Health for Birth Mothers Who Were (a) Faculty and (b) Staff: July 2018

For nonbirth parents, including adoptive and foster parents, 17 schools offered paid parental leave, and 9 offered unpaid parental leave. The mean length of paid parental leave was 8.1 weeks (range = 1 week to 1 semester). The length permitted for unpaid leave ranged from 6 weeks to 1 year.

All 25 schools provided a 1-year tenure clock extension for tenure-track faculty who had a new child, available to both birth mothers and nonbirth parents. The number of extensions permitted varied by school, ranging from as few as 1 to as many as 3.

Staff Policies

For staff, 12 schools (48%) provided birth mothers paid childbearing leave, 3 offered paid medical leave (12%), and 17 (68%) offered unpaid childbearing leave (Table 2). For schools offering paid childbearing leave, the mean length was 5.0 weeks. All schools offering paid medical leave for childbearing provided 6 to 8 weeks, although the policies noted that additional time may be provided if recommended by a physician. Time permitted for unpaid leave ranged from 6 weeks to 1 year. Six schools offered both paid and unpaid leave for staff birth mothers.

TABLE 2—

Staff Leave Policies at Top Schools of Public Health in the United States: July 2018

| Birth Mother |

Nonbirth Parent |

||||

| University | Paid Childbearing | Paid Medical | Unpaid Maternitya (Beyond FMLAb) | Paid Parental | Unpaid Parentala (Beyond FMLAb) |

| Boston University | 8 wk | ||||

| Columbia University—officers of administration | Max 6 moc | 6 mo | |||

| Columbia University—support staff | Accrue 1 d per monthc,d | 6 mo | 6 mo | ||

| Drexel University | |||||

| Emory University | 3 wk | 3 wk | |||

| George Washington University | 6 wk | 6 wk | |||

| Harvard University | 4 wk | 8 wk | 1 wk, then 1 y | 4 wk | 1 y |

| Johns Hopkins University | 10 wk | 4 wk | |||

| Ohio State University | 6 wk | 6 wk | 3 wk | ||

| St Louis University | 3 wke | 3 wke | |||

| Tulane University | 4 wk | 6–8 wkf | 4 wk | ||

| University of Alabama - Birmingham | 4 wk | 4 wk | |||

| University of California - Berkeley | Max 4 moc | ||||

| University of California - Los Angeles | Max 4 moc | ||||

| University of Illinois - Chicago | 2 wk | 2 wk | |||

| University of Iowa | 6 wk | 1 wkg | |||

| University of Maryland - College Park | 6 mo | 6 mo | |||

| University of Michigan - Ann Arbor | 6–8 wkc,h | 1 y | 1 y | ||

| University of Minnesota - Twin Cities | 6 wk | 6 wk | |||

| University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill | 12 wk | 12 wk | |||

| University of Pittsburgh | 4 wk | 1 y | 4 wk | 1 y | |

| University of South Carolina | 6 wkg | ||||

| University of South Florida | 6 mo | 6 mo | |||

| University of Texas Houston Health Sciences | |||||

| University of Washington | 22 wk | 4 mo | |||

| Yale University | 26 wk | 26 wk | |||

Note. FMLA = Family Medical Leave Act (Pub L No. 103-3 [1993]).

Accrued personal time can be used to receive pay.

FMLA requires employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for qualified family and medical reasons to employees.

Length is at the discretion of the mother’s physician.

Plus 12 days of medical leave after 1 year of employment. Max of 60 days of medical leave accrued per year.

Depends on time at the university; after 2 years, eligible for 6 weeks of paid leave.

This is a Louisiana law in place in case the employee is not eligible for FMLA.

Only for new adoptive parents.

Uses Extended Sick Time, which is only available after working at the University for 2 years. Otherwise, the leave is unpaid.

For nonbirth parents, including adoptive and foster parents, 13 schools offered paid leave (52%), and 13 offered unpaid leave (1 school offered both). Eleven schools (44%) explicitly excluded new foster parents from their parental leave policy for nonbirth parents (for both faculty and staff). The mean length of paid parental leave for nonbirth parents was 4 weeks.

Some schools imposed restrictions on eligibility based on minimum length of employment or percentage of full-time employment. Eleven (44%) schools required a minimum length of employment for school parental leave policy eligibility, with 7 requiring at least 1 year, 2 requiring 6 months, and 2 requiring 3 months. A 12th school based the permitted length of leave upon how long the staff member had been employed within the institution.

Five schools provided guidance regarding leave policies when both parents were employed by the same institution. Of these schools, 3 provided full leave to each parent, while 2 required the parents to split the leave.

Lactation Policies

Of the 16 (64%) schools with publicly available lactation policies, all were university-wide policies and not specific to the school of public health. Twelve (48%) included guidelines for lactation breaks, typically 20 to 40 minutes, 1 to 3 times a day. However, these policies often included various restrictions, such as explicitly stating that women should use their regular paid breaks for lactation (8 schools) and, if additional breaks are needed, they would be unpaid. Eight (32%) included statements that the university would support lactation for up to 1 year from a child’s birth, 4 allowed for longer than 1 year, and 4 did not specify the length.

In addition, all 25 schools provided information online regarding designated campus lactation spaces. Lactation rooms for all schools were described as consistent with federal requirements that the rooms be private, secure, and not a bathroom. Fourteen schools described features exceeding federal standards, including provision of chairs, tables, accessible electrical outlets, access to sinks, refrigerators for storage, and, more rarely, breast pumps, although the specific features varied across and even within schools.

Childcare Resources

We identified 3 types of childcare centers: on-campus university-run centers, affiliated centers on or near campus, and nonaffiliated centers on or near campus. Eighteen schools had at least 1 on-campus university-run childcare center, with 13 having 2 or more. While some schools with multiple centers described them as being distributed across campus, for others, they were located only on the main campus, which was not where the school of public health was located. Typically, university-run centers were reserved for children of faculty and staff or provided priority admission for university employees. Web sites typically stated that university-run childcare centers had a waiting list and that they would not be able to accommodate all children of faculty and staff.

Five schools had affiliated childcare centers on or near campus, ranging from 1 to 11 per institution. One institution provided no information regarding university-run or affiliated centers.

DISCUSSION

Despite widespread recognition of the public health importance of dedicated time for parents to care for their children in the earliest months of life,1 we found the top 25 schools of public health in the United States had variable policies to support parents following the birth or adoption of a child. Although a majority of schools offered some form of paid childbirth leave, it was not universal. Furthermore, the average length of paid leave for faculty birth mothers was 8 weeks—well short of the 14 weeks recommended by the APHA. As schools of public health have an important role in setting standards related to parental leave and related policies for infant and maternal health, this inconsistency deserves attention. When we considered policies for staff, the gap between recommendations and actual policies was even greater, with fewer than half (12/25) providing any form of paid leave for birth mothers, raising questions of equity.

Previous literature suggests that these gaps may undermine public health goals. For example, the lack of paid maternity leave may undermine the likelihood that women meet recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months.22 In the first month a mother returns to working outside the home, she has 2.18 times higher odds of breastfeeding cessation as those who are not working outside the home.23 Conversely, women who take longer leave are more likely to initiate breastfeeding and to breastfeed beyond 3 months.22,24 Furthermore, while staff were less likely than faculty to receive paid leave and, on average, to have shorter leave durations, they likely face greater barriers to continuing breastfeeding after returning to work. Previous literature indicates that professional women, such as academic faculty, are significantly more likely to breastfeed than women in other occupations.25,26 Several factors likely contribute to this difference, including greater autonomy, privacy, and freedom to accommodate breastfeeding, as well as greater access to employer-sponsored breastfeeding programs, even within the same company.27,28 That these differences likely also exist in the context of public health institutions is notable, given the longstanding commitments of public health to address health disparities related to income and socioeconomic status.29

Additional shortcomings exist related to the reliance of institutions on accrued vacation time or sick leave in lieu of providing dedicated parental leave. For example, birth mothers who require bed rest during pregnancy may exhaust their available paid leave before delivery, leaving them with little if any paid leave after giving birth. Reliance on accrued leave can also be challenging for those with uncomplicated pregnancies, leaving individuals without leave days for illness (personal or of their infant) following their return to work. Schools that are committed to enabling their faculty and staff to attain recommended standards for breastfeeding and other maternal–infant health goals should consider extending the paid leave available to birth mothers.

Second, family leave policies can be extremely difficult to ascertain. While all schools in this study had publicly available policies, policies were often unclear, difficult to categorize, and potentially contingent upon obtaining proof of medical necessity. Furthermore, as we discovered in contacting institutional representatives to confirm the accuracy of our classifications, oversight of relevant policies was often siloed across multiple administrative departments, which can create challenges for individuals who wish to ascertain their institution’s leave policies. Such complexities are particularly concerning when viewed against the backdrop of longstanding patterns of pregnancy-based discrimination in employment in the United States, as women may be understandably reticent to inquire about maternity leave policies out of concern for undermining their prospects for hiring or advancement.30 Furthermore, in some settings, the duration of leave taken is viewed as a signal of a parent’s commitment to her career, which may encourage some women to dedicate less time to their infants than is recommended.16

Third, our results suggest that many individuals employed by schools of public health may lack reliable access to on-site childcare. On-site childcare offers several potential advantages for new parents, reducing commute times, enabling mothers to nurse during the work day, and offering all parents additional opportunities to bond with their children.31 It also serves an expressive function, signaling an institutional commitment to supporting parents in the workplace.

Fourth, deficiencies in policies related to parental leave, accommodations for nursing mothers, and childcare are associated with a persistent gender gap in academia. Women are substantially less likely to achieve tenure, to receive federal grant support, and to be senior authors of papers published in prestigious medical journals.32–35 It is estimated that women are only half as likely as men to attain senior leadership roles in academic medicine, after controlling for academic productivity.32 We identified several features that may similarly perpetuate this gap in schools of public health. For example, paid leave for nonbirth parents was less common, and for shorter duration, than was paid leave for birth mothers. While this may reflect a recognition of the real and important physical impact of pregnancy and childbirth, it may also reinforce gendered norms regarding caretaking responsibilities.

Crafting policies that both recognize and accommodate the physical impact of childbirth on women while facilitating shared responsibility for childcare between parents, regardless of gender, is no easy task. As noted previously, all schools in our sample provided tenure clock extensions to both birth mothers and nonbirth parents. Yet at least 1 study has found that gender-neutral tenure clock-stopping policies, while intended to “level the playing field,” may nevertheless disproportionately benefit men, exacerbating gender-based promotion disparities.36 Additional research is needed to guide the development of policies that both acknowledge where birth mothers are different and promote gender-neutral caregiving policies.37

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. We included policies for the top 25 schools of public health, but we recognize that these policies may not be generalizable to other institutions. Furthermore, although we contacted the schools we studied to confirm accurate interpretation of policies, our findings may deviate from the lived experiences of those within the institution. For example, previous research suggests that policies may vary at the department or other organizational group level. Such variation complicates the ability of potential parents to prospectively research relevant policies. In addition, our data do not capture the experience of students within schools of public health, who may face additional challenges related to their dual roles as both learners and caretakers. Finally, while our results suggest that policies within schools of public health may not support expressed goals related to parent–child health, future research is needed to examine the effects of longer duration, standardized leave policies on outcomes of interest, including infant feeding practices and on the academic gender gap.

Public Health Implications

We found that policies for faculty and staff at top schools of public health often fall short of public health policy statements related to the health of new mothers and their infants. Given the critical role of public health institutions in modeling policies to support infant and maternal health, schools should take steps to better enable their faculty and staff to dedicate time to be with their infants in the earliest months of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

We did not receive external funding for this project, nor do we have any conflicts to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This project did not involve research with human participants.

Footnotes

See also Kozhimannil, p. 651.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burtle A, Bezruchka S. Population health and paid parental leave: what the United States can learn from two decades of research. Healthcare (Basel) 2016;4(2):E30. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4020030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Public Health Association. A call to action on breastfeeding: a fundamental public health issue. Policy No. 200714. 2007. Available at https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/29/13/23/a-call-to-action-on-breastfeeding-a-fundamental-public-health-issue. Accessed July 6, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Addati L, Cassirer N, Gilchrist K. Maternity and Paternity at Work: Law and Practice Across the World. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin R. Despite potential health benefits of maternity leave, US lags behind other industrialized countries. JAMA. 2016;315(7):643–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajizadeh M, Heymann J, Strumpf E et al. Paid maternity leave and childhood vaccination update: longitudinal evidence from 20 low-and-middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heymann J, Raub A, Earle A. Creating and using new data sources to analyze the relationship between social policy and global health: the case of maternity leave. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3 suppl):127–134. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD003517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islami F, Liu Y, Jemal A et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2398–2407. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li DP, Du C, Zhang ZM et al. Breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(12):4829–4837. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.12.4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma X, Zhao LG, Sun JW et al. Association between breastfeeding and risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018;27(2):144–151. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarz EB, Nothnagle M. The maternal health benefits of breastfeeding. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):603–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartick MC, Schwarz EB, Breen BD et al. Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(1):e12366. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdulwadud OA, Snow ME. Interventions in the workplace to support breastfeeding for women in employment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006177. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006177.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Family Physicians. Breastfeeding, Family Physicians Supporting (position paper). 2014. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-support.html. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- 15.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Optimizing support for breastfeeding as part of obstetric practice. Committee Opinion 658. 2016. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Optimizing-Support-for-Breastfeeding-as-Part-of-Obstetric-Practice. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- 16.Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riano NS, Linos E, Accurso EC et al. Paid family and childbearing leave policies at top US medical schools. JAMA. 2018;319(6):611–614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariton E, Matthews B, Burns A et al. Pregnancy and parental leave among obstetricians and gynecology residents: results of a nationwide survey of program directors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):199.e1–199.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itum DS, Oltmann SC, Choti MA, Piper HG. Access to paid parental leave for academic surgeons. J Surg Res. 2019;233:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Public Health Association. Support for paid sick leave and family leave policies. Policy No. 20136. 2013. Available at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/16/11/05/support-for-paid-sick-leave-and-family-leave-policies. Accessed February 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics. Leading pediatric associations call for congressional action on paid family leave. February 7, 2017. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAPPPCFamilyLeaveAct.aspx. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- 22.Baker M, Milligan K. Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: evidence from maternity leave mandates. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):871–887. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimbro RT. On-the-job moms: work and breastfeeding initiation and duration for a sample of low-income women. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(1):19–26. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogbuanu C, Glover S, Probst J, Liu J, Hussey J. The effect of maternity leave length and time of return to work on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1414–e1427. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visness CM, Kennedy KI. Maternal employment and breastfeeding: findings from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):945–950. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurinij N, Shiono PH, Ezrine SF et al. Does maternal employment affect breast-feeding? Am J Public Health. 1989;79(9):1247–1250. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murtagh L, Moulton AD. Working mothers, breastfeeding, and the law. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):217–223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen L. A comprehensive framework for accommodating nursing mothers in the workplace. Rutgers Law Rev. 2007;59(4):885–916. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Lochner K, Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(9):1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morain SR, Fowler LR, Roberts JL. What to expect [when your employer suspects] you’re expecting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1597–1598. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold K. On-site childcare is a win for everyone. Just ask Patagonia. Outside Online. March 1, 2017. Available at: https://www.outsideonline.com/2159706/why-site-childcare-essential. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 32.Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE et al. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the national faculty survey. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1694–1699. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature—a 35 year perspective. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):281–287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA et al. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O et al. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149–1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antecol H, Bedard K, Stearns J. Equal but inequitable: who benefits from gender-neutral tenure clock stopping policies? Am Econ Rev. 2018;108(9):2420–2441. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams JC, Lee J. Is it time to stop stopping the clock? The Chronicle of Higher Education. August 9, 2016. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/Is-It-Time-to-Stop-Stopping/237391. Accessed November 1, 2018.