The recent growth in public health undergraduate degree programs has been remarkable, with the number of degree conferrals increasing from 750 in 1992 to 6500 in 2012 and 13 000 in 2016.1 This growth is in part a reflection of the attention to undergraduate public health education by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) in its Framing the Futures Initaitive2 and the inclusion of “stand-alone” undergraduate degree programs in accreditation standards of the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH).3 These undergraduate degree programs span a wide variety of institutional settings, from those with both accredited undergraduate and graduate degree programs (e.g., Johns Hopkins University) to those with only an undergraduate program (e.g., Clemson University). Discussions on the purpose and focus of undergraduate degree programs range from “the educated citizen and public health model”4 to a more intentional workforce preparation focus.5

The degree to which such growth has affected the public health workforce has not been previously documented to our knowledge. What we do know is that only a small portion of the public health workforce (14%) has had any formal education in public health.6 This prompted our exploration of public health undergraduate degrees among employees who responded to the 2014 and 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS), as described in the analytic essay by Sellers et al. (p. 674) in this issue of AJPH. The essay focuses on five major themes: workforce diversity, the aging workforce, workers’ salaries and recruiting new staff, the growth of undergraduate public health education, and workers’ awareness and perceptions of national trends in the field.

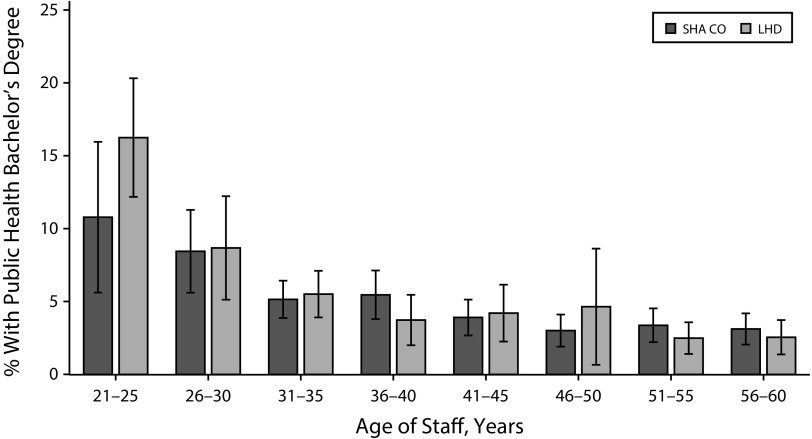

We provide further perspectives on one of the five themes—the growth of undergraduate public health education—and its impact on the public health workforce. Overall, in 2014, 505 of 22 288 (2.3%) state and local health department employees had an undergraduate public health degree. In 2017, that increased to 1851 of 43 701 (4.2%). Those with versus those without an undergraduate public health degree tended to be younger (as shown in Figure 1 and Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) and were more likely to have had a previous job in public health, be a contract or intern employee, be employed in public health sciences (e.g., epidemiologist, environmentalist, or sanitarian), have a higher salary, and have a further higher public health degree. What can we glean from these findings to better understand and prepare for how the growth of undergraduate public health academic programs might shape the public health workforce of the future? We render our opinions on this question, which we raise for purposes of further debate and discussion across public health academia and practice.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of State Health Agency Central Office (SHA CO) Staff and Local Health Department (LHD) Staff With a Public Health Bachelor’s Degree, by Age and Setting: Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey, United States, 2017

CONSEQUENCES

We surmise that there are several potential consequences of the growth in undergraduate public health degree programs, with a mixture of what we deem to be positive and negative. These perspectives arise from our collective experiences in both academia and public health practice.

The Upside

The growth in undergraduate education expands the potential for having more public health employees with at least some level of formal training in public health compared with earlier years when formal training was limited to those with an MPH, DrPH, or PhD. This is already shown by the increase in the percentage of health department employees with an undergraduate public health degree identified in the two PH WINS—from 2.3% in 2014 to 4.2% in 2017.

If we consider the public health system writ large—which includes all individuals, organizations, and agencies that contribute to the health of the public—then even if the graduate with a bachelor’s degree in public health does not work for a governmental health agency but rather some other entity within the larger public health system, we will have a more public health–informed workforce overall. In other words, if the graduate with a bachelor’s degree in public health goes to medical school or gets a job at the YMCA or with Susan G. Komen, she or he can apply knowledge of population health and community health programs (i.e., development, implementation, evaluation) to clinical practice or to those organizations’ initiatives. The limited data available on where students are going after graduation indicate that such penetration may already be taking place. From 2014 to 2015 data on 1300 graduates, ASPPH reported that more than 75% were employed and 12% were pursuing further education; of those employed, 34% worked at for-profit institutions, nearly 20% at health care organizations, and only 11% at governmental organizations.1,7

For the graduate with a bachelor’s degree in public health, creating a bachelor’s to MPH path that is a 3 + 2 or 4 + 1 degree pathway shortens the time and lessens the financial burden of graduate school. This may attract more students to public health academic programs overall and more advanced public health degree holders to the job market.

The Downside

The growth in undergraduate public health education may flood the job market and displace those with an MPH from entry-level positions in governmental public health agencies. With the ongoing challenges of providing competitive salaries in governmental health agencies compared with nonprofit organizations and the private sector, it may simply be easier to hire a person with a public health bachelor’s degree and “train them up” to an MPH-equivalent knowledge level through years of experience on the job.

Undergraduate public health students may overwhelm governmental public health practice, nonprofit agencies, and other community organizations with the experiential activities (e.g., unofficial internships or work experience) requirement of public health bachelor’s degrees. The 2016 revised CEPH accreditation standards require baccalaureate programs to provide students “opportunities to integrate, synthesize and apply knowledge through cumulative and experiential activities,” and “schools and programs [should] encourage exposure to local-level public health professionals and/or agencies that engage in public health practice.”3 The governmental public health agency may not have the capacity to attend to this student body and at the same time provide field placement sites (e.g., practicums, internships) for MPH, DrPH, and many other health professional students.

Academic programs will grow faster than CEPH has the capacity to accredit, threatening a reduction in quality to the lowest possible denominator, which may subsequently have negative repercussions for the workforce. Considering the expansion of accredited schools and programs, the growth of all academic degree programs—undergraduate, MPH, and doctoral—has been phenomenal over the past 20 years.

THE NEED FOR ADDITIONAL DATA POINTS

The Sellers et al. article describes major workforce themes identified with both the 2014 and 2017 PH WINS data; the two data points provide a starting place for identifying trends. But just as any good public health surveillance requires regular repetition, we will need regular, consistent fielding of surveys such as PH WINS to create a public health workforce surveillance system that informs both practice and academia. Such data will be critical to examining the potential upsides and downsides of expanding undergraduate public health degree programs. All of the speculations included in this editorial should be put to the test, but in the meantime we encourage debate and discussion about the changing academic landscape for public health and how that can best shape the future public health workforce.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the helpful reviews and comments provided by AJPH editor-in-chief Alfredo Morabia, MD, PhD, and associate editor Luisa N. Borrell, DDS, PhD.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

See also Sellers et al., p. 674.

REFERENCES

- 1.Resnick B, Leider JP, Riegelman R. The landscape of US undergraduate public health education. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(5):619–628. doi: 10.1177/0033354918784911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. Recommended critical component elements of an undergraduate major in public health. 2012. Available at: https://www.aspph.org/teach-research/models/undergraduate-baccalaureate-cce-report. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- 3.Council on Education for Public Health. 2016 revised criteria. 2016. Available at: https://media.ceph.org/wp_assets/2016.Criteria.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2016.

- 4.Riegelman RK, Albertine S. Undergraduate public health at 4-year institutions: it’s here to stay. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(2):226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wykoff R, Khoury A, Stoots JM, Pack R. Undergraduate training in public health should prepare graduates for the workforce. Front Public Health. 2015;2:285. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sellers K, Leider JP, Harper E et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey: the first national survey of state health agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S13–S27. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. ASPPH presents characterizing undergraduate public health education within the academic public health continuum. 2017. Available at: https://www.aspph.org/event/aspph-presents-characterizing-undergraduate-public-health-education-within-the-academic-public-health-continuum. Accessed January 7, 2019.