Abstract

Public health workforce development efforts during the past 50 years have evolved from a focus on enumerating workers to comprehensive strategies that address workforce size and composition, training, recruitment and retention, effectiveness, and expected competencies in public health practice.

We provide new perspectives on the public health workforce, using data from the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey, the largest nationally representative survey of the governmental public health workforce in the United States.

Five major thematic areas are explored: workforce diversity in a changing demographic environment; challenges of an aging workforce, including impending retirements and the need for succession planning; workers’ salaries and challenges of recruiting new staff; the growth of undergraduate public health education and what this means for the future public health workforce; and workers’ awareness and perceptions of national trends in the field. We discussed implications for policy and practice.

Public health workforce development during the past 50 years has evolved from a focus on enumerating workers to comprehensive strategies that address workforce size and composition, training, recruitment and retention, effectiveness, and expected competencies in public health practice. The increasing prioritization of workforce development is warranted, as it is an important means through which the public health system can improve the public’s health.1 Nearly 20 years ago, the federally supported Task Force for Public Health Workforce Development recommended that the field adopt 6 core strategies for strengthening the workforce: monitoring and projecting workforce supply, identifying competencies on which to base curricula, designing integrated learning systems, promoting public health practice competencies, conducting evaluations of and research on workforce development efforts, and ensuring support for lifelong learning.2 The framework supporting these strategies has shifted over the years as public health paradigms move from being process oriented, with a service delivery focus, to being outcome oriented, with an emphasis on using evidence-based interventions to improve population health.3,4

Workforce development has been guided by more recent efforts (e.g., the Chief Health Strategist and Health in All Policies work) that elevate a systems perspective and identify mechanisms by which governmental public health leaders can eliminate health inequities.5 In addition, numerous task forces, committees, and consortia have convened to outline new workforce development initiatives for public health. There is widespread agreement, for example, that governmental public health workers must be proficient in cultural competency and understand how to address social determinants of health as a means for reducing health disparities and meeting the needs of underserved populations.1 Further, strategic skill needs have been defined for workers,6 health departments have identified workforce development barriers and gaps,7 and workforce data collection has become more standardized through the development of the public health workforce taxonomy8 as well as the data harmonization efforts of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) and the National Association of County and City Health Officials.9

We provide new perspectives on the public health workforce using data from the second Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS), fielded in 2017. We identify 5 major thematic areas that merit further consideration. Three of these themes pertain to the current state of the workforce—workforce diversity in a changing demographic environment; challenges of an aging workforce, including impending retirements and the need for succession planning; and workers’ salaries and challenges of recruiting new staff—and 2 relate to the future workforce—the growth of undergraduate public health education and workers’ awareness and perceptions of emerging concepts in the field of public health.

Understanding workforce size and composition is crucial for effective planning. Public health workforce enumerations have been used for this purpose; such studies have been published periodically since 1926 with varying scope and depth.10 The Health Resources and Services Administration published the largest systematic enumeration of the governmental and nongovernmental public health workforce in 2000.11 A follow-up study in 2014 focused on enumerating the governmental public health workforce as the core of the public health system.12 Subsequently, PH WINS became the most comprehensive effort to collect information on worker characteristics.13,14 Collectively, studies over the past 10 years have summarized workforce changes resulting from recession-related budget cuts,15 identified education and training deficiencies,13 and projected workforce turnover.16 Findings that estimate shortages of US public health workers align with global projections.17

The inherent challenges of developing a public health workforce to meet population health needs are often complex and nuanced. Current workforce settings range from 1-person local health departments serving fewer than 1000 people to large metropolitan health departments with thousands of employees and budgets in excess of $1 billion and to state health agencies that may be a part of larger, umbrella agencies that include Medicaid, health care licensure, and environmental regulation and protection.9,18 Moreover, the workforce and the demands on it are not static, and agency leaders are continuously challenged by forces of change that must be anticipated, including the Affordable Care Act, demographic transitions, and the tidal wave of social media.19 As demands and population needs change, so do the requisite training and competencies of the workforce. An empowered, satisfied, diverse, competitively compensated, well-trained workforce is arguably the key element that can enable agencies to drive improvements in health outcomes.

CONDUCTING THE SURVEY

The de Beaumont Foundation and ASTHO created PH WINS in response to a broad need expressed by leaders in the field to advance workforce development.13,20 The survey is the field’s first large-scale effort to create a nationally representative sample of governmental public health staff at the state and local levels; it is designed around 4 primary domains: training needs, workplace environment, emerging concepts in public health, and demographics. The instrument incorporated a number of previously used items, including the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Technical Assistance and Service Improvement Initiative: Project Officer Survey; the 2009 Epidemiology Capacity Assessment; the Public Health Foundation Worker Survey; and the CDC and University of Michigan Public Health Workforce Taxonomy.8,21–24 The exact items and descriptions are available elsewhere, and the instrument is provided in the appendix (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).25

PH WINS was fielded in 2014 and 2017; we highlight the implications of the 2017 survey for public health practice. PH WINS 2017 had 2 nationally representative frames: 1 for state health agency (SHA) central offices and 1 for local health departments (LHDs), including large LHDs that were members of the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC). The SHA central office frame was constructed by gathering staff lists directly from SHAs (47 of 50 participated). Agencies participated as a census, with all SHA staff receiving an invitation to participate.25 Overall, approximately 48 000 SHA central office staff were invited to participate in the study, and 17 136 permanently employed SHA central office staff responded. The response rate was 35% for the SHA central office frame after accounting for incorrect e-mail addresses, bounce backs, and those who had left their position. Because several SHAs also had local employees, these were parsed out of the SHA central office frame and assigned to the local frame. A defining feature of the SHA central office frame was that all potential respondents were directly invited by ASTHO to participate; this was done in part to manage workflow and reminders and in part to foster trust that all responses would be confidential (and individual records would never be shared with agencies).

The LHD frame was nationally representative of local public health workers at agencies serving 25 000 people or more and with 25 or more staff members. It is not representative of smaller LHDs. Agencies were contributed with certainty from states with nondecentralized governance (including 1 BCHC LHD), and 25 additional BCHC LHDs were contributed with certainty directly. Staff participated from 71 LHDs that had been selected on a stratified probability basis.25 The response rate was 59% for the local frame. For both frames, we used balanced repeated replication weights to adjust variance estimators for complex design and nonresponse.

A strong response rate across several demographic groups has allowed detailed, granular analyses regarding the current and future state of the workforce. Key findings from PH WINS, as well as their practical implications, are our focus in this essay and in accompanying editorials in this issue of AJPH.26–28

THE CURRENT STATE OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Researchers have used PH WINS to examine multiple aspects of the governmental public health workforce.13 Yet, the value of PH WINS lies well beyond research, as there is much more that can and should be said about the practice-based implications of the data. In this essay and accompanying editorials, we provide insight into the utility of PH WINS for practice-based work, using PH WINS data and comparing findings with complementary data sources, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Our discussion focuses on 3 sets of findings about the current state of the public health workforce—diversity, anticipated retirements, and impact of salary on recruitment and retention—and 2 sets of findings about anticipated future developments—educational attainment and the rise of undergraduate public health programs and awareness of emerging concepts in the governmental public health workforce.

Diversity

Diversity is a key indicator in workforce development.1 More diverse and representative workforces are better able to serve diverse populations, because of cultural, environmental, and other considerations.29 Yet most employees at federal, state, and local health departments are non-Hispanic White.30 One exception is that most employees at BCHC health departments are people of color.31 The underrepresentation of people of color is even more substantial at supervisory and managerial levels. Nationally, PH WINS data show that about 30% of non-Hispanic White employees serve in supervisory, managerial, and executive positions, whereas 24% of employees of color do (P ≤ .001). Among SHA central office employees of color, 51% work in clerical or administrative positions; however, at the LHDs of BCHC, just 42% do (P ≤ .001). With respect to educational attainment, 16% of White staff and 21% of staff of color had no college degree (P ≤ .001), 69% of White staff had a bachelor’s versus 64% for staff of color (P = .003), 28% of each had a master’s (P = .73), and 5% of each had a doctorate (P = .25).32 Educational attainment varied by setting, with SHA central office staff and the LHDs of BCHC staff having comparable attainment, which was higher than that of staff from other LHDs.

In addition to characterizing demographic differences, PH WINS presents significant implications for practice, as it captures differences in perceptions (Table 1). The perception that supervisors and team leaders work well with employees of different backgrounds was several points higher among non-Hispanic White employees than with employees of color, except in BCHC health departments. More non-Hispanic White employees than employees of color indicated that their supervisor supports their need to balance work and family. Job satisfaction followed a similar pattern, although White employees were slightly more satisfied with their job at all levels (not statistically significant). Although not controlled for management level or job series, in general, White employees were far more satisfied with their pay than were employees of color (ranging between 6 and 7 percentage points higher across all 3 settings).

TABLE 1—

Staff Perceptions Captured in PH WINS 2017 by Agency Type and Respondent Race/Ethnicity: United States

| SHA Central Office |

BCHC LHD |

Other LHD |

||||

| Perception | White, % | Of Color, % | White, % | Of Color, % | White, % | Of Color, % |

| Communication between senior leadership and employees is good in my organization | 45 | 49*** | 44 | 50*** | 51 | 52 |

| Creativity and innovation are rewarded | 44 | 42 | 48 | 44* | 47 | 42 |

| Employees have sufficient training to fully use technology needed for their work | 51 | 54*** | 53 | 56 | 58 | 64 |

| Employees learn from one another as they do their work | 84 | 80** | 85 | 81** | 85 | 81*** |

| I am determined to give my best effort at work every day | 93 | 94 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 95 |

| I am satisfied that I have the opportunities to apply my talents and expertise | 68 | 66*** | 70 | 69 | 75 | 72 |

| I feel completely involved in my work | 80 | 81 | 83 | 83 | 86 | 86 |

| I have had opportunities to learn and grow in my position over the past year | 72 | 67*** | 74 | 68** | 75 | 67*** |

| I know how my work relates to the agency’s goals and priorities | 86 | 89*** | 89 | 90 | 90 | 91 |

| I recommend my organization as a good place to work | 68 | 66* | 73 | 72 | 72 | 72 |

| My supervisor and I have a good working relationship | 84 | 81*** | 84 | 81* | 84 | 79*** |

| My supervisor provides me with opportunities to demonstrate my leadership skills | 69 | 66** | 69 | 68* | 71 | 66* |

| My supervisor treats me with respect | 85 | 83*** | 86 | 82*** | 85 | 85 |

| My training needs are assessed | 52 | 53 | 52 | 56 | 62 | 61 |

| Supervisors in my work unit support employee development | 74 | 69** | 75 | 70*** | 75 | 68*** |

| Supervisors work well with employees of different backgrounds | 74 | 68*** | 76 | 70* | 76 | 68* |

| The work I do is important | 93 | 94* | 94 | 95 | 96 | 95* |

| I am satisfied with my job security | 75 | 73 | 78 | 74 | 74 | 66 |

| I am satisfied with my job | 80 | 79 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 83 |

| I am satisfied with my organization | 69 | 69 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 73 |

| I am satisfied with my pay | 51 | 45*** | 64 | 58 | 50 | 43** |

Note. BCHC = Big Cities Health Coalition; LHD = local health departments; PH WINS = Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey; SHA = state health agency. Margin of error varies between ±1% and ±3%.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

These differences in perceptions indicate areas for improvement in creating inclusive workplaces in public health departments. If public health leaders want the workforce to reflect the population it serves, ensuring that public health departments provide environments that are welcoming and satisfying for workers of all backgrounds is necessary.

Retirement and Succession Planning

One of the most salient findings of PH WINS has been that a high percentage of staff plan to retire or are considering leaving their organization for other reasons.14,30,33 PH WINS 2017 found that approximately 22% of staff were planning to retire by 2023 and 24% were considering leaving their organization for reasons other than retirement in the coming year.13 Although it appears that high proportions of staff have delayed retirement, and not all who said they were considering leaving did so,16 the workforce is still ripe for significant change. The proportion of staff considering leaving in 2017 was 41% higher than in 2014. This has especially serious consequences in terms of the loss of institutional knowledge and experienced leadership when considering employees in management and executive positions.

Recent research has shown that political appointees, especially chief executives and state health officials, have a relatively short tenure, an average of only 3 years.32 Senior deputies and other managers and leaders who are key to the transfer of institutional knowledge and smooth transitions between changes in leadership at the highest level are some of the most at risk to retire in relatively large numbers. Across agencies, managers and executives account for 11% of staff but 16% of all years of experience in the agency. About 30% of managers and executives say they plan to retire within 5 years, accounting for 42% of all managerial or executive years of experience. Using national weights, we estimate that if all 37 000 staff from SHAs and LHDs serving 25 000 or more people with 25 or more staff retire as planned by 2023, agencies will lose 742 000 years of experience in public health practice collectively. As Beitsch et al. argue in their editorial, looming retirements mean that succession planning, which is still somewhat uncommon among public health agencies, must become a priority.27

IMPLICATIONS FOR RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

Salary affects recruitment and retention, not just in public health but across all fields.34 A wealth of research shows that dissatisfaction with pay is a driver of turnover—in some fields a major or even primary driver.34

Although salary is important in public health, other factors appear to be more substantial in public health workers’ decision-making processes.33,35 In general, across the governmental public health workforce, 48% of SHA workers, 60% of BCHC LHD workers, and 47% of other LHD workers report being satisfied or very satisfied with their pay (not controlled by job series or management level). Among workers considering leaving, 30% were somewhat or very satisfied with their pay, compared with 56% of those who were not considering leaving (P ≤ .001). Comparatively, 58% of those considering leaving indicate they are somewhat or very satisfied with their job (as opposed to their pay), versus 90% of those not considering leaving (P ≤ .001). An interesting question emerges from these observations. If salary is a significant motivator—but not the only motivator and perhaps not the primary motivator for those who are considering leaving their job36—why is salary frequently brought up by managers as the most significant barrier to recruitment and retention?

As shown in the Yeager et al. editorial in this issue,26 we might consider comparing public health salary to national estimates. Overall, staff at SHAs and the LHDs of BCHC make $55 001 to $65 000 on median, and staff at other LHDs earn $45 001 to $55 000.26 Nationally, even from positions that have been identified as susceptible to competition from the private sector, we observe equivalence between public health staff earnings and all other sectors. However, analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicate state-based effects, as the gap between earning potential in government versus the private sector is substantial in certain states. For example, nurses in state and local public health agencies earn up to $15 000 less than their private sector counterparts.37 This salary gap undoubtedly is a significant challenge to recruitment and retention into governmental public health.

THE FUTURE STATE OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Substantial potential for retirements is the culmination of a decade of warnings with an impending “silver tsunami” of retirements caused by baby boomers aging out of the workforce. When that happens, who will take their place? In addition, what kind of awareness do retiring and younger staff have of emerging concepts shaping the public health field?

Undergraduate Training

Although public health has long treated the MPH as the de facto entry degree into the field,1 a substantial upswing in undergraduates with public health bachelor’s degrees is underway. Undergraduate public health degrees have grown from 750 conferred nationally in 1992 to 13 000 in 2016.38 Considering that just 14% of the workforce has a public health degree at any level, and that new hires are more likely to have public health training, undergraduate public health degrees could be an important input into the workforce in the future.

Overall, 1851 of 43 701 (4%) PH WINS respondents reporting their educational attainment had an undergraduate public health degree, comprising 4.3% of SHA employees, 5.5% of BCHC LHD employees, and 4.0% of other LHD employees. Staff whose highest educational attainment was a bachelor’s degree tended to be younger: 38% of public health undergraduate degree holders were aged 35 years or younger, compared with 20% of bachelor’s degree holders with nonpublic health majors (P ≤ .001). Public health bachelor’s degree holders were more frequently employed in public health sciences (e.g., epidemiologist, environmentalist, health educator, or sanitarian) than in administrative or clinical positions. Additionally, 63% of employees whose highest degree was in undergraduate public health were in public health sciences, compared with 24% of others with a bachelor’s as the highest-level degree. Erwin et al. discuss the implications, both positive and potentially negative, of increasing undergraduate public health degree conferrals for the future of public health.28

Perceptions of Emerging Concepts

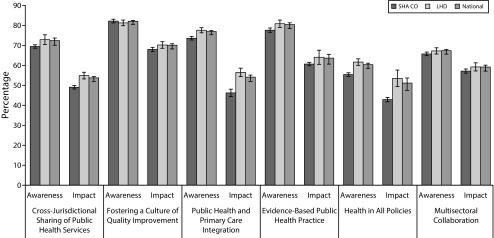

A final future-facing domain captured in PH WINS 2017 relates to emerging concepts in public health (Figure 1). Respondents who had heard of these concepts were asked to rate the impact on their own work.25 Of the concepts examined, the awareness level was lowest for “health in all policies” (60%), compared with 67% for “multisectoral collaboration,” 72% for “cross-jurisdictional sharing,” 76% for “public health and primary care integration,” 80% for “evidence-based public health,” and 81% for “fostering a culture of quality improvement.” Among those who had heard of these concepts, a modest proportion felt the concepts affected their day-to-day work—50% for health in all policies, 53% for cross-jurisdictional sharing, 53% for public health primary care integration, 58% for multisectoral collaboration, 63% for evidence-based public health, and 69% for fostering a culture of quality improvement.

FIGURE 1—

Public Health Workforce Awareness and Perceived Impact of Emerging Concepts in Public Health: PH WINS, United States, 2017

Note. LHD = local health departments; PH WINS = Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey; SHA CO = state health agency central offices. Awareness includes those who said they had heard of the trend “not much,” “a little,” or “a lot.” Impact includes those who had heard of the concept and indicated that it would affect their day “fair amount” or a “great deal.”

Awareness of these emerging concepts is important because their adoption by public health agencies could have a highly positive impact on public health practice and population health outcomes in communities served by these agencies. The awareness levels of these concepts may be more meaningful when viewed in the context of the employees’ perceptions of the impact of each concept on their day-to-day work. Although the pattern was not entirely consistent, the concepts with low awareness were the ones for which perceived impact on the day-to-day work was also low.

BUILDING THE PUBLIC HEALTH WORKFORCE WE NEED

PH WINS provides actionable information for workforce development, yielding practical recommendations for researchers, public health practitioners (especially leaders), and other decision-makers.

Researchers should continue supporting state and local health departments’ needs for evidence-based information to mine PH WINS data for actionable insights and combine them with other data sources to put them in context and increase their potential. They should also use the data to evaluate the effectiveness of workforce development interventions.

Public health agency leaders have a role in facilitating the creation of comprehensive workforce development plans aligned with staff training needs. These plans should emphasize a culture and policies to improve diversity and inclusion. Employees at all levels should be engaged in developing the plan, with leaders serving as champions. Decision-makers at all levels of government can work to optimize the transfer of institutional knowledge and expertise as more experienced staff leave the workforce. As PH WINS salary data highlight, decision-makers can also focus their attention on specific highly competitive positions, including nurses, epidemiologists, informaticians, and laboratorians. In the clinical field, clinicians have shifted to performing at “the top of their license” to focus their attention where it is most needed.7 Public health agencies can follow a similar model with their more competitive positions, concentrating resources on a smaller number of high-skilled positions. Ensuring that all workers perform to the top of their abilities, giving them “stretch” assignments, and pushing more routine tasks to workers with less expertise and experience are necessary.

Direct supervisors can also emphasize the importance of the most important emerging concepts, such as multisector partnerships, cross-jurisdictional sharing, and health in all policies approaches to prepare workers for the future that seems most likely. Supervisors play a role in ensuring that workers are getting the training needed to develop strategic skills, including understanding and influencing policy, systems thinking, and communicating persuasively. Leaders should facilitate employees having the space to practice new skills as they are learned to increase the chances that the benefits of the training accrue to the employee and the health department. Participating agencies have used their agency-specific results to guide their workforce development initiatives, including targeted trainings, setting baselines for employee engagement initiatives, and developing workforce development plans required for accreditation through the Public Health Accreditation Board. Other agencies have focused on specific measures from PH WINS to address key issues affecting their workforce and agencies, including improving organizational communication and employee retention.

The public health workforce needs coordinated leadership by a task force including representatives of federal, state, local, and interested nonprofit entities. This workforce task force should develop an aligned vision for the public health workforce of the future and either invest in or advocate investments in efforts to make that vision a reality. The task force should ensure that key frameworks such as the Foundational Public Health Services acknowledge the importance of a robust and effective workforce. If national public health leaders rely on frameworks that do not emphasize the importance of the workforce, critical investment in developing a capable workforce will never materialize.

Continued surveillance and analysis of training needs, understanding of key concepts, and other workforce changes will be essential for ensuring that the governmental public health system has the capabilities needed to protect and improve the nation’s health. Future iterations of PH WINS and other data sources will help elucidate trends and needs, but investment in making the identified changes is critical. A third wave of PH WINS will take place in 2020, which will provide additional insight into demographic trends, a culture of diversity and inclusion, retirement, recruitment and retention, educational attainment, and the workforce’s awareness and adoption of emerging concepts in public health. Collaborative and aligned leadership, increased investment in workforce development, and continued monitoring and evaluation of efforts will be required to build the governmental public health workforce we need.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey was funded by the de Beaumont Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was determined to be exempt by NORC at the University of Chicago institutional review board.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Gebbie KM, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thacker SB. Guide for applied public health workforce research: an evidence-based approach to workforce development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15(6 suppl):S109–S112. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181b1eb85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeSalvo KB, Wang YC, Harris A, Auerbach J, Koo D, O’Carroll P. Public Health 3.0: a call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E78. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.170017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Ahmed S, Franco Z et al. Towards a unified taxonomy of health indicators: academic health centers and communities working together to improve population health. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):564–572. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RESOLVE. The high achieving governmental health department in 2020 as the community chief health strategist. 2014. Available at: http://www.resolv.org/site-healthleadershipforum/files/2014/05/The-High-Achieving-Governmental-Health-Department-as-the-Chief-Health-Strategist-by-2020-Final1.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 6.National Consortium for Public Health Workforce Development. Building skills for a more strategic public health workforce: a call to action. 2017. Available at: https://www.debeaumont.org/wp-content/uploads/Building-Skills-for-a-More-Strategic-Public-Health-Workforce.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 7.Beck AJ, Leider JP, Coronado F, Harper E. State health agency and local health department workforce: identifying top development needs. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1418–1424. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck AJ, Coronado F, Boulton ML, Merrill JA Public Health Enumeration Working Group. The public health workforce taxonomy: revisions and recommendations for implementation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(5):E1–E11. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. ASTHO profile of health, volume 4. 2017. Available at: http://www.astho.org/Profile/Volume-Four/2016-ASTHO-Profile-of-State-and-Territorial-Public-Health. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 10.Merrill J, Btoush R, Gupta M, Gebbie K. A history of public health workforce enumeration. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9(6):459–470. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebbie KM. Columbia University School of Nursing; Center for Health Policy; National Center for Health Workforce Information and Analysis. The public health work force: enumeration 2000. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; 2000.

- 12.Beck AJ, Boulton ML, Coronado F. Enumeration of the governmental public health workforce, 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5, suppl 3):S306–S313. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellers K, Leider JP, Harper E et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey: the first national survey of state health agency employees. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S13–S27. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogaert K, Castrucci B, Gould E et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS 2017): an expanded perspective on the state health agency workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S16–S25. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck AJ, Boulton ML. Trends and characteristics of the state and local public health workforce, 2010–2013. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 2):S303–S310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leider JP, Coronado F, Beck AJ, Harper E. Reconciling supply and demand for state and local public health staff in an era of retiring baby boomers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(3):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JX, Goryakin Y, Maeda A, Bruckner T, Scheffler R. Global health workforce labor market projections for 2030. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0187-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Association of County and City Health Officials. 2016 National profile of local health departments. 2017. Available at: http://nacchoprofilestudy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ProfileReport_Aug2017_final.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 19.Erwin PC, Brownson RC. Macro trends and the future of public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:393–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman NJ, Castrucci BC, Pearsol J et al. Thinking beyond the silos: emerging priorities in workforce development for state and local government public health agencies. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(6):557–565. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulton M, Hadler J, Beck AJ, Ferland L, Lichtveld M. Assessment of epidemiology capacity in state health departments, 2004–2009. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(1):84–93. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Office of Personnel Management. Federal employee viewpoint survey results. 2014. Available at: https://www.opm.gov/fevs/reports/data-reports. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 23.Public Health Foundation. Public Health Workforce Survey Instrument. 2010. Available at: http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Public_Health_Worker_Survey.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 24.Ironson GH, Smith PC, Brannick MT, Gibson W, Paul K. Construction of a job in general scale: a comparison of global, composite, and specific measures. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(2):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leider JP, Pineau V, Bogaert K, Ma Q. The methods of PH WINS 2017: approaches to refreshing nationally-representative state-level estimates and creating nationally-representative local-level estimates of public health workforce interests and needs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S49–S57. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeager VA, Leider JP. The role of salary in recruiting employees in state and local governmental public health: PH WINS 2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):683–685. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beitsch L, Yeager VA, Leider JP, Erwin PC. Mass exodus of state health department deputies and senior management threatens institutional stability. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):681–683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erwin PC, Beck A, Yeager VA, Leider JP. Public health undergraduates in the workforce: a trickle, soon a wave? Am J Public Health. 2019;109(5):685–687. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satcher D. The importance of diversity to public health. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(3):263. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leider JP, Harper E, Shon JW, Sellers K, Castrucci BC. Job satisfaction and expected turnover among federal, state, and local public health practitioners. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1782–1788. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juliano C, Castrucci BC, Leider JP, McGinty MD, Bogaert K. The governmental public health workforce in 26 cities: PH WINS results from Big Cities Health Coalition members. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S38–S48. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halverson PK, Lumpkin JR, Yeager VA, Castrucci BC, Moffatt S, Tilson H. Research full report: high turnover among state health officials/public health directors: implications for the public’s health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5):537–542. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pourshaban D, Basurto-Davila R, Shih M. Building and sustaining strong public health agencies: determinants of workforce turnover. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S80–S90. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffeth RW, Hom PW, Gaertner S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J Manage. 2000;26(3):463–488. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellers K, Leider JP, Bogaert K, Allen JD, Castrucci BC. Making a living in governmental public health: variation in earnings by employee characteristics and work setting. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S87–S89. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogaert K, Leider JP, Castrucci B, Sellers K, Whang C. Considering leaving, but deciding to stay: a longitudinal analysis of intent to leave in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S78–S86. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment, hours, and earnings from the Current Employment Statistics Survey (National). 2018. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/ces/highlights122018.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- 38.Leider JP, Castrucci BC, Plepys CM, Blakely C, Burke E, Sprague JB. Characterizing the growth of the undergraduate public health major: US, 1992–2012. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(1):104–113. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]