Abstract

Besides cardiomyocytes (CM), the heart contains numerous interstitial cell types which play key roles in heart repair, regeneration and disease, including fibroblast, vascular and immune cells. However, a comprehensive understanding of this interactive cell community is lacking. We performed single-cell RNA-sequencing of the total non-CM fraction and enriched (Pdgfra-GFP+) fibroblast lineage cells from murine hearts at days 3 and 7 post-sham or myocardial infarction (MI) surgery. Clustering of >30,000 single cells identified >30 populations representing nine cell lineages, including a previously undescribed fibroblast lineage trajectory present in both sham and MI hearts leading to a uniquely activated cell state defined in part by a strong anti-WNT transcriptome signature. We also uncovered novel myofibroblast subtypes expressing either pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic signatures. Our data highlight non-linear dynamics in myeloid and fibroblast lineages after cardiac injury, and provide an entry point for deeper analysis of cardiac homeostasis, inflammation, fibrosis, repair and regeneration.

Research organism: Mouse

eLife digest

In our bodies, heart attacks lead to cell death and inflammation. This is then followed by a healing phase where the organ repairs itself. There are many types of heart cells, from muscle and pacemaker cells that help to create the beating motion, to so-called fibroblasts that act as a supporting network. Yet, it is still unclear how individual cells participate in the heart's response to injury.

All cells possess the same genetic information, but they turn on or off different genes depending on the specific tasks that they need to perform. Spotting which genes are activated in individual cells can therefore provide clues about their exact roles in the body. Until recently, technological limitations meant that this information was difficult to access, because it was only possible to capture the global response of a group of cells in a sample.

A new method called single-cell RNA sequencing is now allowing researchers to study the activities of many genes in thousands of individual cells at the same time. Here, Farbehi, Patrick et al. performed single-cell RNA sequencing on over 30,000 individual cells from healthy and injured mouse hearts. Computational approaches were then used to cluster cells into groups according to the activities of their genes.

The experiments identified over 30 distinct sub-types of cell, including several that were previously unknown. For example, a group of fibroblasts that express a gene called Wif1 was discovered. Previous genetic studies have shown that Wif1 is essential for the heart's response to injury. Further experiments by Farbehi, Patrick et al. indicated that this new sub-type of cells may control the timing of the different aspects of heart repair after damage.

Tens of millions of people around the world suffer from heart attacks and other heart diseases. Knowing how different types of heart cells participate in repair mechanisms may help to find new targets for drugs and other treatments.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease including myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western and developing worlds. After acute MI, millions of cardiomyocytes (CM) are lost by necrosis and apoptosis, and an initially adaptive collagen-rich scar is laid down to preserve chamber geometry and prevent rupture. The mammalian heart is regarded as being poorly regenerative as the long-term sequelae in virtually all etiologies of heart disease involve increased wall stiffness, reduced heart function and progression to heart failure. However, some inbred strains of mice show surprising cardiac reparative abilities (Patterson et al., 2017), and CM renewal and heart regeneration can be stimulated experimentally (D'Uva et al., 2015; Mohamed et al., 2018; Srivastava and DeWitt, 2016; Wang et al., 2018), garnering optimism that heart regeneration can be achieved in humans.

Cardiac chamber walls are composed of a complex, interdependent community of interstitial cells, including vascular, fibroblast, immune and neuronal cells, although how they interact in cardiac homeostasis, injury and repair, is relatively unexplored. In regenerative systems, connective tissues play key roles in defining positional information, and organizing tissue architecture and niche environments (Nacu et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2013; Greicius et al., 2018). Cardiac fibroblasts represent ~10% of all cardiac cells (Pinto et al., 2016) and are distributed throughout the cardiac interstitial, perivascular and sub-epicardial spaces, where they are proposed to have sentinel, paracrine, mechanical, extracellular matrix (ECM) and electrical functions (Shinde and Frangogiannis, 2014; Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017). After injury, inflammation is principally executed by poly-functional monocytes (Mo) and macrophages (MΦ), and is necessary to protect against pathogens and autoimmunity, and to coordinate healing. Fibroblasts also participate in inflammation and phagocytosis and are the principal drivers of fibrotic repair (Shinde and Frangogiannis, 2014; Gourdie et al., 2016). In heart repair, timely resolution of inflammation is necessary for limiting fibrosis and enabling tissue replacement, while uncontrolled inflammation leads to increased fibrosis and chamber wall stiffening, poor electro-mechanical coupling, continued loss of CMs and worsening outcomes (Mescher, 2017; Lai et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2018).

The general principles of inflammation and fibrosis have been mapped in different organs, and the implementation of specific lineage-tracing tools has provided significant new insights into cardiac leukocyte and fibroblast origins and fate (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017; Williams et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2018; Ivey et al., 2018; Kanisicak et al., 2016; Moore-Morris et al., 2014; Ensan et al., 2016; Heidt et al., 2014; Molawi et al., 2014; Epelman et al., 2014; Plein et al., 2018). However, controversies persist around nomenclature, defining markers, origins, heterogeneity and plasticity (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017; Epelman et al., 2015; Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018). Even the question of whether the transitions from quiescent to activated fibroblast, then to myofibroblast, should be seen as differentiation in the classical sense, degrees of a scalable and reversible continuum governed by the injury environment, or a branched dynamic network, is unresolved (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017; Ivey and Tallquist, 2016; Travers et al., 2016).

One approach to a deeper understanding of cardiac population biology is through single-cell genomics, including single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Single-cell methods have the power to overcome the limitations of bulk cell analyses, where insights into complex cell system dynamics are lost (Tanay and Regev, 2017). The rich data generated by single-cell methods allow new computational frameworks for inferring cell dynamics and causality, unencumbered by strict a priori notions of cell identity, hierarchy, trajectory and markers.

Here, we present the first comprehensive analysis of cellular lineage heterogeneity, dynamics and intercellular communication among immune and stromal (non-CM) cells in healthy and injured adult mouse hearts using scRNA-seq. Clustering analysis of >30,000 cells identified over 30 cell populations across the total non-CM fraction and enriched (Pdgfra-GFP+) fibroblast lineage cells. These populations comprised most of the known cell types and their dynamics after injury, as well as novel cell types and their intermediates. We describe a novel population of activated fibroblasts present in both sham and injured hearts expressing a strong anti-Wingless-related integration site (WNT) transcriptome signature, a putative pre-proliferative state, and three novel myofibroblast subtypes expressing pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic (including anti-WNT) signatures. We were also able to distinguish the major tissue-resident and infiltrating Mo/MΦ, and numerous minor populations. Overall, our data reveal dynamic, multi-dimensional lineage trajectories in the injured heart. This deep resource will provide novel insights into the inflammatory and fibrotic cascades in the injured mouse heart that may suggest novel molecular or cellular targets for enhancing heart repair and regeneration in man.

Results

Single-cell RNA-seq of total cardiac interstitial cell population

We performed single-cell expression profiling on the total cardiac interstitial cell population (TIP) using the 10x Genomics Chromium platform, from hearts of 8 weeks old male PdgfraGFP/+ mice at days 3 and 7 post-sham or MI surgery. To enrich for cells relevant to cardiac ischemic injury and repair, we isolated TIP cells from dissected ventricles and interventricular septum, excluding cells of the atria, annulus fibrosus and atrioventricular valves (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A).

Transcriptional profiles of 13,331 cells were captured after quality control filtering (sham: 5,723; MI-day 3: 3,875; MI-day 7: 3,733). To identify cells with distinct lineage identities and transcriptional states, we performed unbiased clustering on an aggregate of cells using the Seurat R package (Butler et al., 2018), with cell populations visualized in t-SNE dimensionality reduction plots (Materials and methods). For initial analyses, populations expressing markers of multiple lineages (hybrids) were removed; however, select examples are discussed in more detail below.

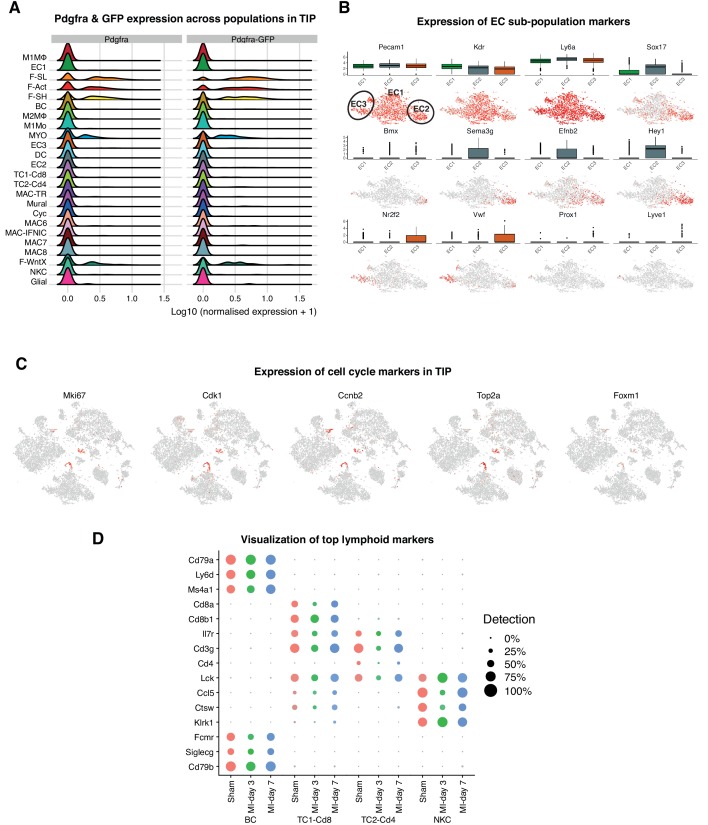

TIP cells were represented by a total of 24 populations and nine distinct cell lineages (Figure 1A–D; Figure 1—figure supplement 1B–F). Major cell types comprised fibroblasts/myofibroblasts (Col1a1+Pdgfra+GFP+), endothelial cells (ECs; Kdr+Pecam1+), mural cells (Cspg4+Pdgfrb+), Mo and MΦ (Cd68+Itgam+), dendritic-like (DC) cells (Cd209a+Itgam+), glial cells (Plp1+Kcna1+), B-cells (Cd79a+Ms4a1+), T-cells (Cd3e+Cd3d+Lef1+) and natural killer cells (NKCs; Klrk1+Ccl5+) (Figure 1A–E; Figure 1—figure supplement 1D; Supplementary file 1). New lineage markers were identified; for example, Vtn, encoding Vitronectin, was specifically expressed in mural cells, whereas Kcna1, encoding the potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 1, was highly specific to glial cells (Figure 1D and Figure 1—figure supplement 1D).

Figure 1. TIP scRNA-seq.

(A) t-SNE plots showing detected lineages and sub-populations in TIP across conditions. (B) t-SNE plot of aggregate TIP cells with identified sub-populations. (C) Dendrogram of sub-populations according to average RNA expression. (D) Expression of select marker genes across TIP cells as visualized on t-SNE plots. (E) Cell population percentages across conditions determined to be significantly modulated according to Differential Proporation Analysis (DPA) (p<0.01).

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Experimental procedures, population proportions and gene expression characterstics of sub-populations within TIP scRNA-seq.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Gene expression data for TIP sub-populations.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Differential proportion analysis (DPA) procedure and evaluation.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Clustering of TIP scRNA-seq prior to removal of minor hybrid populations.

Figure 1—figure supplement 5. A typical workflow of sequential gating strategy for doublet exclusion is shown.

Figure 1—figure supplement 6. FACS data supporting F-EC population.

Figure 1—figure supplement 7. FACS data supporting the M2 MΦ -EC population.

Figure 1—figure supplement 8. Atrial Fibrilation (AF) associated genes in TIP.

Within the fibroblast lineage, we identified several sub-populations, each marked by expression of Pdgfra, Pdgfra-GFP, Col1a1 and other canonical fiboblast markers (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017; Ivey and Tallquist, 2016) (Figure 1A–D; Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). We describe these in more detail after enrichment below.

There were three major sub-populations of ECs (EC1, EC2, EC3), comprising vascular and lymphatic lineages (Pecam1+Kdr+Ly6a+) (Figure 1D; Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). The majority EC1 population expressed Ly6a (encoding SCA1) as well as the vascular transcription factor (TF) Sox17, and likely represents microvascular ECs. EC2 expressed canonical arterial endothelial markers such as Bmx, Sema3g and Efnb2, as well as TF genes Sox17 and Hey1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B), the latter acting downstream of NOTCH which is required for arterial EC fate. EC3 almost uniquely expressed venous EC marker Nr2f2 (encoding COUPTFII) and Von Willebrand factor (Vwf), and a minority (~3%) expressed Prox1 and Lyve1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B), consistent with a lymphatic identity. A small number of ECs were cycling (Cyc; Figure 1A–C; Figure 1—figure supplement 2C). Our EC data are broadly consistent with recently published single-cell data (Zhao et al., 2018).

Among lymphocytes, a single B-cell population (BC) expressed Cd79a, Ms4a1 and Ly6d (Figure 1D; Figure 1—figure supplement 2D). T-cell sub-populations TC1-Cd8 (Cd8a+) and TC2-Cd4 (Cd4+Lef1+) likely represent cytotoxic and helper T-cells, respectively. NKCs exclusively expressed Klrk1 and upregulated Lck, Ccl5 and Ctsw (Figure 1—figure supplement 2D).

Differential proportion analysis for detecting cell population dynamics

We observed major injury-induced cellular responses and flux after MI, including expansion of Mo/MΦ populations at MI-day 3, as well as myofibroblasts and an additional MΦ population at MI-day 7 (Figure 1A; Figure 1—figure supplement 1B,C). To analyze whether changes in the proportion of populations were greater than expected by chance, we developed a novel permutation-based statistical test (differential proportion analysis; DPA) that considered sources of variation which could arise from experimental procedures (such as differing cell numbers and cell-type capture bias) or in silico analysis (cluster assignment accuracy) (Materials and methods; Figure 1—figure supplement 3A–H). DPA identified 12 populations showing significant (p<0.01) flux between conditions (Figure 1E; Supplementary file 2); for example, the fibroblast sub-populations F-SL and F-SH (see below) decreased sharply in proportion at MI-day 3, while M1 and M2 MΦ populations expanded at days 3 and 7 after MI, respectively.

Monocyte/macrophage cell identity and dynamics

Cardiac tissue-resident MΦ originate from CX3CR1+ progenitors in the yolk sac and Mo from fetal liver and post-natal bone marrow (Ensan et al., 2016), and have roles in immunity, coronary artery and pacemaker development, and heart regeneration (Lavine et al., 2014; Hulsmans et al., 2017). Resident MΦ are long lived and self-renewing (Epelman et al., 2014; Bajpai et al., 2018), although some are supplanted by blood-derived Mo with age or injury (Heidt et al., 2014; Molawi et al., 2014; Dick et al., 2019). MI triggers a biphasic cascade of inflammation and remodeling, with the acute phase involving early influx of neutrophils and CCR2+LY6C2high pro-inflammatory M1 Mo/MΦ, which phagocytose debris and secrete pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα to amplify the inflammatory response (Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018). The repair phase begins around MI-day 3 when non-classical LY6C2-F4/80high M2 MΦ accumulate and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as Il-10 and TGF-β, and stimulate angiogenesis (Epelman et al., 2015; Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018).

In sham hearts, we identified cardiac tissue-resident MΦ with the signature Cx3cr1highAdgre1(F4/80)highH2-Aa(MHC-II)+Itgam(CD11b)lowLy6c2lowCcr2- (MAC-TR; Figure 1A,B; Figure 2A–D) (Ensan et al., 2016; Epelman et al., 2014; Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018; Lavine et al., 2014; Lavine et al., 2018). Recent work using flow cytometry and scRNA-seq has delineated several subsets of cardiac tissue-resident MΦ, including a pro-regenerative population with the signature TIMD4+LYVE1+MHC-IIlowCCR2-, that self-renew and are not replaced by blood monocytes even after injury (Dick et al., 2019). We could discern this same population at the scRNA-seq level as a subset within MAC-TR, which persisted after injury (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A; Figure 2B). The additional major subset of CCR2- tissue-resident MΦ (Dick et al., 2019) could also be recognised at the scRNA-seq level as the Timd4-Lyve1-H2-Aa(MHC-II)highCcr2- subset of MAC-TR – this population has been shown to have a low monocyte dependence during homeostasis but is almost fully replaced by monocytes after MI (Dick et al., 2019).

Figure 2. Cardiac Mo/MΦ populations.

(A) t-SNE plot showing extracted Mo/MΦ populations. (B) Expression of select immune cell markers as visualized in box-plots and t-SNE plots. Arrows indicate Ccr2low sub-population of M2MΦ. (C) Dot-plot of top upregulated genes for each Mo/MΦ population where color indicates experimental conditions. (D) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between Mo/MΦ populations with representative significant GO Biological Process terms.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Mo and MΦ marker genes and Diffusion Map analysis.

Among other minor resident Mo/MΦ populations detected, the most abundant (pale green cells in Figure 1A,B) clustered with the M2 MΦ present at MI-day 7. In fact, all minor Mo/MΦ populations in sham hearts aligned with adult monocyte-derived Mo/MΦ populations which influx after MI (Figure 1A,B), consistent with recent findings (Dick et al., 2019). A prominent B-cell, and minor DC, T- and NK cell populations were also present in sham hearts. These populations may represent a mixture of resident cells and those involved in homeostatic immunosurveillance (Lavine et al., 2018), although we cannot exclude a response to sham operation.

At MI-day 3, a major influx population was identified as classical blood-derived M1 Mo, based on the signature Adgre1(F4/80)+Itgam(CD11b)+Fcgr1(CD64)+Ly6c2highCcr2highH2-Aa(MHC-II)low (M1Mo; Figure 2A–C) (Epelman et al., 2015; Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018). Differentially expressed genes showed Gene Ontology (GO) term over-representation for cell migration, inflammation and T cell activation (Figure 2D). In FACS, Mo are distinguished from MΦ by having lower size and granularity, and lower levels of MΦ markers including Adgre(F4/80), Itgam(CD11b) and H2-Aa(MHC-II) (Bajpai et al., 2018; Hilgendorf et al., 2014). M1Mo identified at MI-day 3 were also low or negative for other MΦ markers Siglec1, Mrc1, Maf, Trem2 and Mertk, the latter involved in phagocytosis (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A) (Bajpai et al., 2018), and C1 complement genes C1qa, b and c (Figure 2C), which are involved (in addition to complement fixation) in recruitment of new inflammatory cells and protection against autoimmunity (Emmens et al., 2017; Thielens et al., 2017).

The more abundant population at MI-day 3 was identified as classical Mo-derived M1 MΦ based on the signature Ccr2highAdgre1(F4/80)+Ly6c2+H2-Aa(MHC-II)+ (M1MΦ; Figure 1A,B; Figure 2A–D). This assignment was supported by expression of the additional MΦ markers cited above, including Mertk and C1q, and hierarchical clustering, which showed M1MΦ to be most closely related to M1Mo (Figure 1C), as for human cognates (Bajpai et al., 2018). Differentially expressed genes showed GO term over-representation for leukocyte migration and responses to interleukin-1 (Figure 2D).

The most prominent population at MI-day 7 was identified as non-classical M2 MΦ involved in inflammation resolution and repair, with the signature Ccr2highAdgre1(F4/80)+H2-Aa(MHC-II)highLy6c2- (M2MΦ; Figure 1A,B; Figure 2A–D) (Epelman et al., 2015; Swirski and Nahrendorf, 2018). Differentially expressed genes showed GO term over-representation for antigen presentation via MHC class II (Figure 2D). As expected, the non-classical M2 MΦ population increased late during injury repair from <2% of TIP in sham and MI-day 3 hearts, to 16% at MI-day 7. Interestingly, the population dendrogram showed that M2MΦ were most closely related to MAC-TR (Figure 1C), and similarities between resident and subsets of infiltrating Mo/MΦ have been discerned recently using single-cell methods (Dick et al., 2019). Both MAC-TR and M2MΦ expressed Cx3cr1, often used to define tissue-resident MΦ (Figure 2B), and both upregulated pro-regenerative genes Igf1 (Figure 2B) and Pdgfb/c (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). The majority of M2MΦ were Ccr2high (important for migration); however, a minor sub-populaion was Ccr2low (arrows, Figure 2B) and these expressed the highest levels of Igf1 and lower levels of MHC-II (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). In this sense they are similar to the CCR2-MHC-IIlow subset of tissue-resident MΦ which appear to be yolk sac-derived (Dick et al., 2019; Leid et al., 2016), and which play a role through expression of IGF1 and IGF2 in remodeling of the fetal coronary vascular plexus (Leid et al., 2016). However, whether in the adult post-MI heart they represent persisting resident cells or an infiltrating population that has matured into a MAC-TR-like MΦ state will require lineage mapping approaches.

Il10, associated with the anti-inflammatory functions of M2MΦ, was expressed in only few cells in our dataset and may be at the limit of detection (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). Expression of mouse genes encoding cognates of human CD14 and CD16/FCGR3, previously used to define classical, non-classical and intermediate Mo in human blood (Villani et al., 2017), did not help to discrimate the above Mo/MΦ populations, nor did new markers recently highlighted from CyTOF analysis (Williams et al., 2018). Moreover, the M2MΦ marker Arg1 (encoding Arginase 1) was more lowly expressed in M2MΦ described here than in M1MΦ, consistent with findings that ARG1 does not always mark M2 cells (Jablonski et al., 2015). Neither the M2 MΦ, nor any other myeloid population, expressed Col1a genes, likely precluding the presence of myeloid-derived fibroblasts (Duerrschmid et al., 2015).

Diffusion Map (Angerer et al., 2016) analysis applied to model possible temporal (pseudotime) changes in major Mo/MΦ populations (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C) revealed a continuum of states resolved into a trajectory from early infiltrating M1Mo (left) and inflammatory M1MΦ (centre), to the late peaking M2MΦ (right), similar to a recent scRNA-seq study (Dick et al., 2019) and consistent with the current model in which M1 Mo differentiate into M2 cells in situ (Lavine et al., 2018; Hilgendorf et al., 2014). The Diffusion Map also demonstrated the convergence of M2MΦ present at MI-day 7 with tissue-resident MΦ (MAC-TR) in sham hearts, a relationship reflected in the population dendrogram (Figure 1C; see Discussion).

The minor myeloid populations also showed different expression profiles and dynamics (Figure 1A–C,E; Figure 2A–D). For example, MAC6 showed upregulation of granulocyte markers including S100a9 and Csf3r (Supplementary file 3), with sub-populations expressing markers of neutrophils (Ly6g) and eosinophils (Siglecf) (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). MAC-IFNIC cells showed strong upregulation of interferon (IFN)-induced genes including Ifit3, Ifit1 and Cxcl10 (Figure 2C), consistent with GO term analysis implicating responses to IFN α, β, and γ (Figure 2D). These cells appear to arise from Ccr2+ MΦ as opposed to monocytes (Dick et al., 2019), and likely correspond to the recently described inflammatory MΦ subtype that has negative effects on heart repair after MI through promotion of inflammatory cell types, and cytokine and chemokine expression (King et al., 2017).

Cell-cell communication analysis in TIP

We constructed cell-cell communication networks with weighted edges reflecting expression fold-changes of ligands and receptors in source and target populations, respectively (Materials and methods). Ligand-receptor interactions were derived from a curated map of human ligand-receptor pairs (Ramilowski et al., 2015) with mouse-specific weights added after reference to the STRING database (Szklarczyk et al., 2017). Based on permutation testing of randomized network connections, 91 cell-cell relationships with weighted paths higher than expected by chance (Padj <0.01) were identified (Figure 3A–B). Myofibroblasts (MYO) and MΦ populations M1MΦ and MAC-8 exhibited the largest number of outbound connections, with MYO having the highest weight. ECs by far showed the largest number and weighting of significant inbound connections. Strikingly, fibroblast populations (F-SH, F-SL, F-Act and F-WntX) appeared to communicate exclusively with vascular (ECs and mural) and glial cells. In line with this result, immunofluorescence analysis of sham and MI-day 3 hearts showed that Pdgfra-GFP+ fibroblasts were observed in close spatial relationships or direct contact with CD31+ endothelial cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A–B).

Figure 3. Cell-cell ligand-receptor network analysis.

(A) Hierarchical network diagram of significant cell-cell interaction pathways. Arrows and edge color indicates direction (ligand:receptor) and edge thickness indicates the sum of weighted paths between populations. (B) Comparison of total incoming path weights vs total outgoing path weights across populations. (C) Summed ligand weights across souce ligand and receptor target paths for top ligands in MYO. (D) Tree plot showing outgoing connections from the Glial cells. Top node refers to source population, second layer to ligands, third layer to receptors and leaf nodes represent target populations.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Pdgfra-GFP+ cells localization in healthy and diseased hearts.

Top-weighted interactions involving MYO were driven mostly by ECM-associated ligands including COL1a1, COL1a2, Fibronectin 1, Pleiotrophin, COL3a1, COL5a2, Biglycan, Metalloprotease inhibitor one and COL5a1, that can engage with receptors expressed in numerous populations (Figure 3C). The minority glial cell population expressed canonical neuronal glia markers, including Plp1, Prnp and Gfra3 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D), and likely support cardiac sympathetic nerves essential for cardiac regeneration in neonates (Mahmoud et al., 2015). Glial cells also appeared to communicate with the three EC populations and mural cells (Figure 3A), consistent with the phenomenon of neurovascular congruence in the cardiac sympathetic plexus (Stubbs et al., 2009). In support of this, we detected eight ligands highly specific to glial cells (expressed in <5% of other TIP cells) including Dhh (Desert Hedgehog) and Semaphorin genes Sema3b and Sema4f (Figure 3D), involved in both neural and angiogenic development (Gamboa et al., 2017). Thus, these maps suggest the extent, directionality and complexity of interactions between cardiac cell types in homeostasis and injury.

Hybrid populations in TIP

We detected five minor populations expressing markers of two lineages (Figure 1—figure supplement 4A–D). Such ‘hybrid’ cells may betray trans-differentiation events or doublets in proximity that are resistant to the conditions of dissociation. Microdroplet microfluidics platforms are also known to generate a significant number of doublets (Zheng et al., 2017a); thus, the provenance of hybrid cells requires independent validation.

ECs are highly plastic and endothelial-to-mesenchyme transition (EndMT) has been reported to generate fibroblasts after cardiac injury (Kovacic et al., 2019). Conversely, cardiac fibroblasts have been observed to transdifferentiate to ECs (Ubil et al., 2014), albeit that this has been disputed (He et al., 2017). The F-EC hybrid population co-expressed markers of fibroblasts and ECs, and segregated with other fibroblast populations (Figure 1—figure supplement 4A–C). To explore this population, we isolated interstitial cells from dissected ventricles of PdgfraGFP/+ mice after sham or MI surgery, and asked whether we could detect GFP+CD31+ cells using flow cytometry and a stringent gating strategy that excluded cell aggregates (Materials and methods; Figure 1—figure supplement 5A–D). We detected 2.4 ± 0.28% of GFP+CD31+ cells in sham hearts, 1.51 ± 0.26% in MI-day 7 hearts, and none in controls (Figure 1—figure supplement 6A–E) - thus, while double positive cells were found, they did not appear responsive to injury.

An ability of Mo/MΦ to transdifferentiate into endothelial-like cells in different settings has been documented in vitro and in vivo, and has therapeutic implications (Das et al., 2015), although a natural plasticity in Mo toward an endothelial cell fate in vivo does not have strong support (Basile and Yoder, 2014). The M2MΦ-EC hybrid population co-expressed markers of ECs (Kdr+Pecam1+Sox17+ Efnb+Mcam+) and M2MΦ (Ccr2highAdgre1[F4/80]+H2-Aa[MHC-II]highCx3cr1+Mrc1[CD206]+Ly6 c2-), and segregated with M2MΦ (Figure 1—figure supplement 4A,B). Flow revealed 0.56 ± 0.02% single live CD31+CD45+ cells in sham-day 7 hearts, increasing to 4.04 ± 1.03% in MI-day 7 hearts, demonstrating an increase in injury (Figure 1—figure supplement 7A–C). Among these, 35.67 ± 3.01% were F4/80+CD206+ (a signature of M1 and M2 MΦ) in sham hearts, increasing to 60.03 ± 4.60% in MI-day 7 hearts. It is well known that the expression of EC markers on the surface of bone-marrow-derived cells is insufficient to define them as ECs, although they can be angiogenesis promoting cells (Basile and Yoder, 2014). While these data do not exclude the possibility of doublet formation in our scRNA-seq experiments, they support the existence of distinct F-EC and M2MΦ-EC populations with hybrid qualities and different responses to injury. These warrant further investigation.

Single-cell RNA-seq of the Pdgfra-GFP+ cardiac fibroblast lineage

A major subset of fibroblasts in the uninjured adult murine heart express the cell surface stem/progenitor cell markers SCA1 and/or PDGFRα (Kanisicak et al., 2016; Asli et al., 2017; Chong et al., 2011; Noseda et al., 2015). However, when fibroblasts differentiate into MYO, they reduce these markers and express fibrogenic (e.g. Periostin; POSTN) and/or contractile (e.g. αSmooth Muscle Actin; αSMA) proteins (Fu et al., 2018). To circumvent the dominance of immune cells in TIP following MI, which dilute out other cell populations, and to focus on fibroblast sub-populations (Figure 1A), we performed single-cell expression profiling on PDGFRα+CD31- cardiac interstitial cells at days 3 and 7 post-sham or MI. GFP fluorescence from PdgfraGFP/+ mice was used as a surrogate lineage tracing tool and enabled us to capture both GFPhigh fibroblasts as well as their derivatives in MI mice, including MYO (Asli et al., 2017). We sorted for GFP+CD31- cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A), although did not use SCA1 as an index marker so as to capture the substantial Pdgfra-GFP+ fibroblast population that is negative or low for SCA1 expression (Figure 4—figure supplement 1B).

We performed unbiased clustering on an aggregate of the 16,787 cells (Materials and methods), identifying 11 sub-populations (Figure 4A–D; Figure 4—figure supplement 1C–F). The two sham conditions showed high concordance (Figure 4—figure supplement 1E,F) and are displayed merged (Figure 4A,B) unless indicated. All populations showed expression of canonical fibroblast markers Pdgfra, GFP, Ddr2 and Col1a1, albeit at varying proportions and levels (Figure 4E), and major changes in cell proportions were seen between conditions (Figure 4D). Here, we refer to ‘activated fibroblasts’ and myofibroblasts (MYO) as distinct cell entities, without prejudice about their stability, origin, fate or contractile nature.

Figure 4. Pdgfa-GFP+ scRNA-seq.

(A) t-SNE plot of GFP+ cells separated according to experimental condition (sham, MI-day 3, MI-day 7). (B) t-SNE plot showing aggregate of GFP+ cells across conditions. (C) Dendrogram of populations determined by average RNA expression in populations. (D) Percentages of cells in each population according to experimental condition. Stars indicate significant change across conditions according to DPA (p<0.01). (E) Expression of select genes in different populations as visualized in box and t-SNE plots. (F) Dot-plot of top five upregulated genes for each population where color indicates strength of expression and size of dot represents percentage of cells expressing the gene.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. FACS profiles and scRNA-seq analysis for GFP+/CD31- cells.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Comparison of GFP+ populations with FACS-sorted S+P+ cells.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Expression of selected marker genes across GFP+ populations visualized in box and t-SNE plots.

Figure 4—figure supplement 4. Population-specific expression of transcription factors marking fibroblast and myofibroblast sub-populations.

Figure 4—figure supplement 5. Comparisons with Skelly et al. (2018) and Gladka et al. (2018) scRNA-seq data-sets.

In sham conditions, two major fibroblast populations could be distinguished on the basis of scRNA-seq. We termed these Fibroblast-Sca1-high (F-SH) and Fibroblast-Sca1-low (F-SL), as the highest upregulated gene in F-SH was Ly6a(Sca1) (Figure 4E; Supplementary file 4). F-SH contained the highest frequency of Pdgfra and Ly6a(Sca1)-expressing cells and likely corresponds to the PDGFRα+SCA1+ (S+P+) population previously defined by FACS (Pinto et al., 2016; Chong et al., 2011) (see also Figure 4—figure supplement 1A) and enriched in cardiac colony-forming mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-like cells (cCFU-F), which show multi-lineage differentiation and self-renewal in vitro (Chong et al., 2011; Noseda et al., 2015). In order to confirm the relationship between F-SH and S+P+, we performed deeper scRNA-seq on 103 FACS-purified S+P+ cells from uninjured wild-type mice using the Fluidigm platform and predicted cell identity using an iterative Random Forest (iRF) classifier (Basu et al., 2018) trained on populations defined in our GFP+ experiments in sham conditions using the Chromium platform (Materials and methods; Figure 4—figure supplement 2A). Approximately 60% of single S+P+ cells analyzed by Fluidigm were predicted to correspond to the F-SH population (Figure 4—figure supplement 2B), compared to <30% among total sham GFP+ cells (Figure 4D), indicating that S+P+ cells are significantly over-represented in F-SH cells (Fisher’s exact test, p=8.13e-11). We previously showed that cCFU-F are enriched in the S+P+ population (Chong et al., 2011; Noseda et al., 2015). THY1/CD90 is a recognised MSC marker, and Thy1 was upregulated in F-SH with high significance (p=4.48e-176; Figure 4—figure supplement 2C). Furthermore, FACS-isolated S+Pdgfra-GFP+CD90.2high cells isolated from healthy hearts showed a ~ 6 fold enrichment in cCFU-F compared to S+Pdgfra-GFP+CD90.2low cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 2D,E). Together, these results show that the F-SH population contains a subset of cells expressing Pdgfra, Ly6a(Sca1) and Thy1(Cd90) that is enriched in cCFU-F, highlighting the distinct expression signatures and functional properties of F-SH and F-SL.

We calculated differentially expressed (DE) genes between F-SL and F-SH in sham conditions (Supplementary file 5). F-SH was characterized by over-representation of genes involved in the biological process (BP) cell adhesion, which included cell surface receptor genes Ackr3(Cxcr-7), Thy1(Cd90), Axl and Cd34. In contrast, F-SL was characterized by GO BP terms signaling and signal transduction (Supplementary file 6). Within the signal transduction category, protein localization prediction with LocTree3 (Goldberg et al., 2014) indicated an over-represented majority (19/28) of secreted proteins (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.03), with 10/19 identified as ligands, including APOE, BMP4 and ADM. Thus, F-SL, a major sub-division of fibroblasts, has a unique secretory phenotype distinct from that in F-SH, which is enriched in MSC-like colony forming cells.

Novel Pdgfra-GFP+ fibroblast populations

We identified two previously unstudied GFP+ fibroblast populations termed Fibroblast - Wnt expressing (F-WntX) and Fibroblast - transitory (F-Trans). These were present in both sham and MI hearts, although had diminished significantly by MI-day 7 (DPA; p<0.01; Figure 4D). In F-WntX, differential gene expression analysis showed that the top upregulated gene was Wif1, encoding a secreted canonical WNT pathway inhibitor essential for cardiac repair after MI (Meyer et al., 2017). WIF1 can also antagonize Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) signaling (Surmann-Schmitt et al., 2012), which plays a supportive role in cardiac fibrosis (Travers et al., 2016). Wif1 was almost uniquely expressed in F-WntX in all conditions (Figure 4E). A single cell in the Fluidigm data corresponded to the F-Wntx population (Figure 4—figure supplement 2B). Multiple other WNT pathway-related genes were upregulated in F-WntX encoding WNT ligands (WNT5a, WNT16), soluble WNT antagonists (DKK3, SFRP2), membrane-bound WNT receptor (FRZB) and AXIN2, a component of the β-catenin destruction complex (see schematic in Figure 5A; Figure 4—figure supplement 3). F-WntX also showed upregulated Fmod, which inhibits fibrillogenesis and sequesters pro-fibrotic factor TGF-β within ECM (Zheng et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2017b) (Supplementary file 4). Overall, this signature suggests an anti-WNT, anti-CTGF and anti-TGF-β extracellular and intracellular signaling milieu for F-WntX cells. F-WntX cells expressed Postn(Periostin), Acta2(αSMA), Tagln(Transgelin) and Scx(Scleraxis), in both sham and MI conditions (Figure 5B; Figure 5—figure supplement 1A), suggesting an activated state even in the absence of injury (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017). The adjacent cluster, F-Trans, did not express activation markers, nor the WNT signature identified in F-WntX, or other uniquely identifying markers; however, cell trajectory analysis, described below, allowed us to assign F-Trans as a transitionary population between F-WntX and F-SL fibroblasts.

Figure 5. Features of the F-WntX population.

(A) Differentially expressed genes in F-WntX overlaid on Wnt pathway maps. Wnt node includes genes Wnt5a and Wnt16. (B) Detection rate, representing the percentage of cells expressing a gene, across all conditions for cells in F-WntX or all GFP+ cells combined. (C) Example GO BP terms over-represented (FDR < 0.05) in genes upregulated in F-WntX compared to F-SL/F-SH populations. (D) Tree plot showing ligand-receptor connections from F-WntX to EC sub-populations as calculated in TIP. Top node refers to source population, second layer to ligands, third layer to receptors and leaf nodes represent target populations. (E) Examples of F-WntX:EC ligand and corresponding receptor expression as visualised in box and t-SNE plots. For each ligand the corresponding receptor is immediately below.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Activation and paracrine signature of F-WntX cells.

We examined DE and GO BP terms in F-WntX compared with F-SL and F-SH combined. Notably, negative regulation of Wnt signaling pathway was over-represented in DE genes for F-WntX (Figure 5C), driven by WNT pathway antagonist genes Wif1, Dkk3, Frzb and Sfrp2, discussed above, as well as Apoe, Nkd1 and Wwtr1, also known to interact with the WNT pathway. BP terms related to negative regulation of development/differentiation, extracellular matrix (ECM) organization and signaling, were also significant. ECM organization terms were over-represented in the adjacent F-Trans (Supplementary file 6), involving genes also upregulated in F-WntX (e.g. Eln[Elastin], Vit[Vitrin] and Mfap4), and others upregulated in F-Trans but not F-WntX, including collagen genes (Col1a1, Col3a1 and Col14a1) and Fbln1(Fibrilin-1).

The top GO BP term in F-WntX was regulation of cell proliferation (Figure 5C); however, F-WntX did not express cell cycle markers under any condition. Analysis of Molecular Function (MF) terms revealed over-representation of signaling receptor binding and growth factor binding (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B), overlapping significantly with regulation of cell proliferation (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C,D; Fisher’s exact test, p<1e-03). In this latter term, there were several cytokine and chemokine genes, including Pdgfa, Tgfb3, Ptn, Ccl19 and Cxcl12, some of which bind receptors that were down-regulated in F-WntX, strongly suggesting paracrine functions related to their expression in F-WntX (Figure 5—figure supplement 1E). A paracrine function for F-WntX was supported by our ligand-receptor analysis, which indicated that F-WntX cells communicate most significantly with ECs (Figure 3A). Analysis of top upregulated ligands in F-WntX connecting to receptors in ECs (Figure 5D) identified several factors such as Ptn(pleiotrophin), Myoc(myocilin) and Timp3(TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 3). Here again, the corresponding receptor was expressed in ECs but downregulated in F-WntX (Figure 5E).

Localization and composition of WIF1+ cells

To explore the location of F-WntX cells and their behaviour after injury, we examined the expression of WIF1 protein in Pdgfra-GFP sham and MI hearts by immunofluorescence (IF), after first confirming that our chosen antibody detected known sites of Wif1 expression in E14.5 embryos (Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Interestingly, we detected WIF1 protein only in the infarct border zone at MI-day 3, but not in sham hearts or at MI-days 1 or 7 (Figure 6A–C, Figure 6—figure supplement 2). In cardiac cells (and some embryonic cells) WIF1 staining was perinuclear, and we demonstrated co-expression of WIF1 and the golgi marker GM130 (Figure 6D), consistent with WIF1 being a secreted protein. We found WIF1 in ~4% of total nuclei of the infarct border zone at MI-day 3, with a fraction of these (~5%) being GFP+ by IF, indicating a fibroblast identity (Figure 6C,I), and overall ~17% were positive for Ki67 (Figure 6E,I). WIF1+ cells were negative for CD31, and negative or very low for αSMA, with rare exceptions (Figure 6F,F’,H). However, WIF1 was also expressed in ~4% of total CD45+ cells in the infarct border zone (~15% of WIF1+ cells were CD45+) (Figure 6G,I). We observed frequent close proximity or contact between WIF1+ cells and CD31+ ECs in tissue sections (Figure 6H), in line with the predicted cell-cell ligand-receptor connection between F-WntX cells and ECs (Figure 3A). Such proximity was less obvious for α-SMA+ or CD45+ cells (Figure 6F,G). Overall, our data suggest that WIF1 expression is post-transcriptionally regulated and injury-dependent, appearing in the infarct border-zone at MI-day 3 in a subset of fibroblasts and immune cells. The temporal window of WIF1 expression overlaps with fibroblast activation and expansion, and the beginning of EC renewal and MYO differentiation.

Figure 6. WIF1 localization and co-expression in injured and uninjured hearts of Pdgfra-GFP+ mice.

(A) Representative image of WIF1 (red), GFP (green) and Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA, grey) co-immunostaining showing the border zone at MI-day 3. Arrowheads show WIF1+ cells. Scale bar - 50 μm. (B–C) Representative images of WIF1 (red) and GFP (green) co-immunostainings showing left ventricle (sham, (B) or infarcted border zone at MI-day 3 (C). Arrowheads show WIF1+ cells, Asterix shows WIF1+GFP+ cells. Scale bars - 20 μm. (D–G) Representative images of co-immunostainings for WIF1 (red), GFP (green) and markers (gray) for golgi (GM130, D, Arrowheads show WIF1+GM130+ cells), proliferation (Ki67, E, Arrowheads show WIF1+Ki67+ cells), smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts (α-SMA, F, (F’) showing an example of a WIF1+GFP+α-SMA+ cell from another section), and leukocytes (CD45, G, Arrowheads show WIF1+CD45+ cells, Asterix shows GFP+CD45+ cells). Scale bar - 20 μm. (H) Representative image of co-immunostaining for WIF1 (green), WGA (gray) and endothelial cell marker CD31 (green). Arrowheads show WIF1+ cells in close proximity/contact with CD31+ cells. Scale bar - 20 μm. (I) Quantification of marker-positive cells in the infarcted border zone of MI-day 3 hearts. n = 4.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. WIF1 expression pattern in E14.5 embryos.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. WIF1 protein expression after sham or MI.

Flux of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts after MI

MI is associated with appearance of activated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. MI-day 7 was characterized by the appearance of a large population of myofibroblasts (MYO), representing 52% of GFP+ cells at MI-day 7 in our data (Figure 4A–D). MYO showed strong upregulation of numerous collagen genes (e.g. Col1a1, Col3a1, Col5a2), as well as Postn (99.5%) and Acta2 (61%) at high levels, indicative of an activated state and suggestive of a contractile phenotype for a subset of cells (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017; Travers et al., 2016) (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 3). Upregulated genes involved in wound healing and cell migration included Fn(Fibronectin) and Cthrc1(Collagen Triple Helix Repeat Containing I), the latter representing a highly specific marker for MYO (Figure 4F). MYO showed decreased expression of Pdgfra, Pdgfra-GFP, Ly6a(Sca1), Thy1(Cd90) and Cd34 (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 2C; Supplementary file 4), indicating loss of stem/progenitor cell markers.

Earlier in the injury process, there was a distinct increase in a population with a signature consistent with activated fibroblasts (Fibroblast: activated; F-Act). These represented 48% of GFP+ cells at MI-day 3, before diminishing to 12% at MI-day 7 (Figure 4A–D). F-Act expressed Postn at high levels in ~80% of cells (Figure 4E) consistent with an activated state (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017). They expressed Acta2 in 28% and 35% of cells at MI-day 3 and MI-day 7, respectively, although at much lower levels compared to MYO, suggesting an emerging contractile phenotype in some cells. On the population dendrogram, F-Act was most closely related to fibroblast populations (F-SH, F-SL, F-Trans) and was more distant from MYO (Figure 4C). Whereas F-Act expressed few genes that could be considered highly specific, the top upregulated gene was Cilp (Figure 4F), encoding a matricellular protein and inhibitor of TGF-β1 signaling, consistent with F-Act being a pre-MYO population in which fibrosis is constrained. The expansion of F-Act at MI-day 3 correlated with a decrease in the proportion of F-SH and F-SL, whereas the diminishment of the F-Act population at MI-day 7 coincided with the appearance of MYO and an apparent partial restoration of F-SH and F-SL cells (Figure 1A,E; Figure 4A,D; see Discussion).

A distinct GFP+ population contained fibroblasts undergoing proliferation (Fibroblast - cycling; F-Cyc), comprising 15% of GFP+ cells at MI-day 3 and 3% at MI-day 7 (Figure 4D), consistent with studies showing peak fibroblast proliferation at MI-days 2–4 (Fu et al., 2018; Ivey et al., 2018). F-Cyc uniquely expressed a strong cell cycle gene signature, including Ccnb2(CyclinB), Cdk1(Cyclin dependent kinase 1) and Mki67(Ki67) (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 3), and expressed both Postn (88%) and Acta2 (76%) at high levels (Figure 4E; see below).

Cell trajectory analysis of Pdgfra-GFP+ cells

To look at potential relationships between the major GFP+ populations, we analyzed cell trajectories using Diffusion Maps (Materials and methods). MYO, F-WntX and F-Cyc were represented as three different trajectories along diffusion components 1, 2 and 3, respectively (Figure 7A), with the root containing the two large unactivated fibroblast populations F-SH and F-SL, which were most prominent in sham hearts. F-Trans was an intermediary population along the trajectory to F-WntX, and F-Act was an intermediary population for both F-Cyc and MYO branches. F-Cyc, characterized by expression of a strong cell cycle gene signature, was represented most strongly at MI-day 3, whereas MYO was exclusively associated with MI-day 7 (Figure 7B,C). These data suggest that F-Act expands by proliferation up to MI-day 3 (F-Cyc trajectory) and differentiates to MYO during the transition from MI-day 3 to MI-day 7. The presence of some F-Cyc-like cells between the F-Cyc and MYO trajectories at MI-day 7 raises the possibility that a small fraction of F-Act cells differentiate rapidly into MYO after or during division (see below).

Figure 7. Diffusion Map analysis of GFP+ cells.

(A) 3D Diffusion Map of main fibroblast/myofibroblast populations with cells colored according to population. (B) 2D Diffusion Map facetted according to experimental condition. (C) Expression of marker genes on main trajectories of diffusion components across conditions. (D) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes with representative GO Biological Process terms.

We examined DE and GO BP terms in F-Act, F-Cyc and MYO compared with F-SL and F-SH combined, across all conditions (Figure 7D; Supplementary file 5; Supplementary file 6). DE genes for F-Act were over-represented in terms for collagen fibril organization (including several collagen genes) and regulation of wound healing. Many of these genes were also expressed in F-Cyc and MYO; however, there was an additional large gene signature strongly upregulated in MYO compared to F-Act (Figure 7D). DE genes for MYO demonstrated GO BP terms for collagen fibril organization and cell adhesion, containing collagen genes Col3a1, Col5a1, Col11a1 and Col14a1, and others involved in cell:cell and cell:matrix adhesion including Thbs1 (encoding Thrombospondin 1) and Fbn1. Other terms included angiogenesis and heart development as well as negative regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway, containing many genes previously identified in F-WntX.

Minor Pdgfra-GFP+ populations

Minor GFP+ populations included epicardial cells (EPI), observed only at MI-day 7. These expressed Wt1 (Figure 4—figure supplement 3) and overall were related transcriptionally to dissected adult mouse epicardium (Bochmann et al., 2010) (Spearman’s correlation test, p=0.014, r = 0.26). These are likely to be epicardial-derived fibroblasts that arise after MI as the epicardium reactivates its developmental program (including Pdgfra expression) (Zhou et al., 2011). Consistent with a previous cardiac scRNA-seq analysis on uninjured hearts (Skelly et al., 2018), we did not detect epicardial cells in TIP data, suggesting that these cells are under-sampled in our experiments - this is likely technical as epicardial cells have been detected readily in single-nucleus RNA-seq (Hu et al., 2018).

The minor population F-IFNS (Fibroblast: Interferon stimulated), found in all conditions, was negative for Cd45 and expressed high levels of Col1a1 and other fibroblast markers (Figure 4E; Figure 4—figure supplement 3), demonstrating a fibroblast identity, and interferon-responsive genes (Figure 4F; Supplementary file 4) (Zhou et al., 2013). Other minor GFP+ populations were EC and MAC (Figure 4A–C), which had EC and MΦ identities, respectively (Materials and methods).

Transcription factors expressed in Pdgfra-GFP+ cells

Several TF genes expressed in GFP+ cells may drive differentiation or responses to environmental stimuli (Figure 4—figure supplement 4). Scleraxis, already mentioned, was expressed in F-WntX cells and MYO. The basic helix-loop-helix factor gene, Tcf21, an accepted marker of cardiac fibroblasts (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017), was expressed in most GFP+ populations with the exception of F-WntX cells. T-box factor gene Tbx20, another fibroblast marker, was expressed across all GFP+ cells and upregulated in F-WntX. The homeodomain TF gene, Meox1, which is part of the cardiac fetal gene expression signature reactivated in injured hearts (Lu et al., 2018), showed upregulation in subsets of GFP+ cells, most prominently in activated populations (F-Act, F-Wntx, F-Cyc and MYO), and may drive the activated state. Csrp2a, Zfp385a and Hmgb2 expression was also restricted among populations, with Csrp2a and Zfp385a showing strikingly complementary patterns. Interestingly, the homeodomain TF gene, Prrx1, which in BM is expressed in a subset of mesenchymal cells with CFU-F and multi-lineage differentiation potential (Kfoury and Scadden, 2015), was expressed across all GFP+ populations in all conditions.

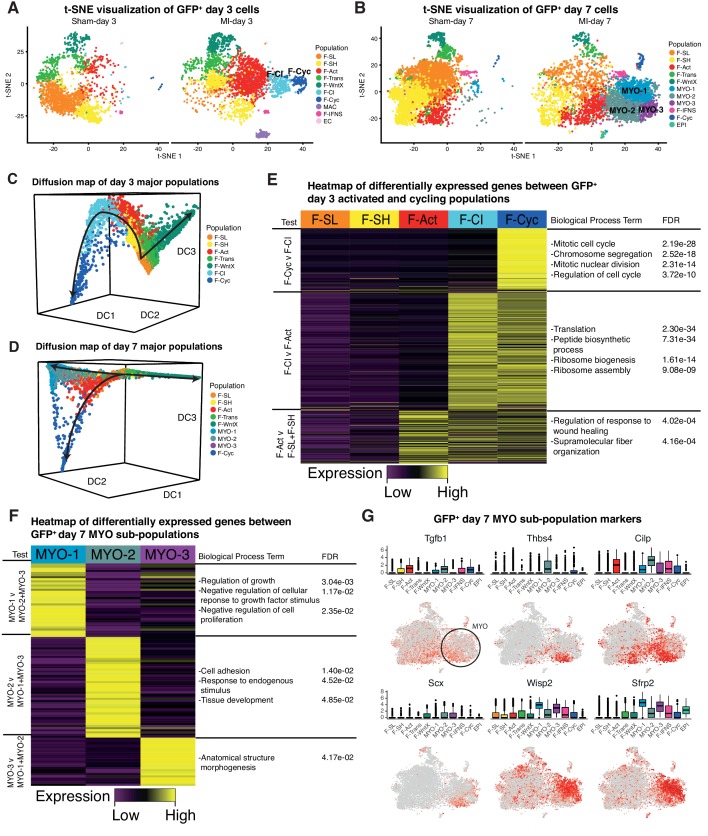

Activated fibroblast and myofibroblast sub-populations

We re-clustered the sham and MI datasets at days 3 and 7 individually (Figure 8A,B), and repeated Diffusion Map analysis of GFP+ fibroblast lineages (Figure 8C,D) (Materials and methods). Whereas most populations identified at day 3 directly corresponded to those identified in the aggregate analysis, we found that F-Cyc could now be sub-divided into two populations, with only one exhibiting a clear cell cycle signature (Figure 8E, Supplementary file 7; Supplementary file 8). An intermediary population (Fibroblast - Cycling Intermediate; F-CI) showed upregulation of fibroblast activation markers including Postn, Cthrc1 and Acta2 (Figure 8—figure supplement 1A), but did not express markers of cell cycle, suggesting that it represents an additional population of activated fibroblasts, potentially competent for cell cycle entry. F-CI also upregulated genes involved in protein translation, a signature absent in F-Act (Figure 8E). The translation signature was maintained, albeit in attenuated form, in F-Cyc. Based on an iRF classifier trained to predict MI-day 3 populations (Figure 8—figure supplement 1B), we found no corresponding F-CI cluster at MI-day 7, indicating its transient nature (Figure 8—figure supplement 1C,D). Diffusion Map analysis also lent weight to the hypothesis that F-CI is a transitory population between F-Act and F-Cyc at MI-Day 3 (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. Time-point-specific analysis of GFP+ scRNA-seq.

(A,B) t-SNE visualization of GFP+ populations 3 days post sham/MI (A) and 7 days post sham/MI (B). (C,D) 3D Diffusion Map analysis of day 3 major populations (C) and day 7 major populations (D). (E) Heatmap of upregulated genes in day 3 injury-response populations. (F) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between myofibroblast sub-populations. (G) Gene expression visualized in box and t-SNE plots for myofibroblast sub-population marker genes.

Figure 8—figure supplement 1. Reanalysis of GFP-day 3 and GFP-day 7 data-sets separately.

We next removed genes annotated with the GO term ‘Cell Cycle’ and re-clustered populations. At MI-day 3, 88% of F-Cyc cells merged with F-CI, strongly supporting the hypothesis that F-CI is a pre-proliferative precursor of F-Cyc (Figure 8—figure supplement 1E). After removal of cell cycle genes at MI-day 7, 65% of F-Cyc cells remained as a distinct (proliferative) population, although 26% merged with F-Act and 6% merged with the MYO populations (Figure 8—figure supplement 1F). Taken together with Diffusion Map analysis, these data indicate that the closest population to the majority F-CI and cycling cells is F-Act rather than MYO, even though both express Acta2 and other MYO markers at high levels (Figure 4E). However, a minority of F-Cyc cells at MI-day 7 may be dividing MYO cells or in transition to MYO (see Discussion). Our data support the idea that F-CI cells are an activated form of fibroblast closely related to F-Cyc and derivative of F-Act. We hypothesize that they are primed for cell cycle entry and differentiation, but this requires further investigation.

In the MI-day 7 re-analysis, we found that MYO could be sub-divided into three clusters - MYO-1, MYO-2 and MYO-3 (Figure 8B,F; Supplementary file 9; Supplementary file 10), and comparing these clusters we noted genes corresponding to the contrasting functions of fibrosis inhibition and promotion. MYO-2 upregulated Tgfb1 (encoding TGF-β1), which is one of the strongest and most studied drivers of MYO formation (Figure 8G; Supplementary file 9), Scx(Scleraxis), which regulates ECM production and the myofibroblast phenotype downstream of TGF-β (Bagchi et al., 2016) and Thbs4(Thrombospondin 4), a regulator of cardiac fibrosis (Frolova et al., 2012). We sourced RNA-seq data from cultured mouse cardiac fibroblasts untreated or treated with TGF-β (Schafer et al., 2017) and extracted DE genes. As expected, the highest positive correlations with TGF-β treatment (log2 fold-changes) were in MYO and other activated fibroblast populations (Supplementary file 11). For inter-MYO comparisons, we found a significant positive correlation with TGF-β treatment in DE genes comparing MYO-2 v MYO-1 (Spearman’s correlation test, r = 0.26, Padj = 1.93e-12) and MYO-3 v MYO-1 (Spearman’s correlation test, r = 0.25, Padj = 1.75e-10), supporting the conclusion that MYO-2 and MYO-3 are pro-fibrotic.

In contrast, MYO-1 showed strong upregulation of anti-fibrosis genes included Wisp2, encoding matricellular protein CCN5 which can reverse established fibrosis (Jeong et al., 2016), and Sfrp2 encoding a soluble WNT receptor and antagonist of canonical WNT signalling, which is pro-fibrotic (Mirotsou et al., 2007) (Figure 8G). MYO-1 upregulated genes showed significant GO terms negative regulation of growth factor stimulus and negative regulation of cell proliferation (Figure 8F; Supplementary file 10), which included Sfrp1, implicated in inhibition of fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Sklepkiewicz et al., 2015), and Htra1 and Htra3, implicated in TGF-β signaling inhibition (Tocharus et al., 2004). Diffusion Map analysis of MYO sub-populations showed that MYO-1 and MYO-2 were distinct clusters with some overlap, suggesting a continuum of states, whereas MYO-3 did not appear to be a distinct population (Figure 8—figure supplement 1G).

Discussion

The mammalian heart is composed of a complex interdependent community of cells, although their interactions and flux are poorly characterized. Here, we present scRNA-seq data on >30,000 individual cardiac interstitial cells from sham, and MI days 3 and 7 hearts. Our interrogation of both the total interstitial population (TIP) and flow-sorted Pdgra-GFP+CD31- fibroblast lineage cells has given us a high-resolution map of cell lineage, state and flux in the healthy and injured heart, considerably extending preliminary studies (Kanisicak et al., 2016; Skelly et al., 2018; Gladka et al., 2018).

On the basis of these data, resident fibroblasts could be segregated into two major sub-populations denoted Sca1high (F-SH) and Sca1low (F-SL), both expressing canonical fibroblast markers such as Pdgfra, Pdgfra-GFP, Ddr2 and Col1a1. F-SH cells were enriched in S+P+ (SCA1+PDGFRα+) fibroblasts and clonal colony-forming units (Pinto et al., 2016; Chong et al., 2011; Noseda et al., 2015), and F-SH and F-SL showed distinct adhesive and secretory phenotypes, highlighting the likely functional differences between them.

We describe a novel activated fibroblast population, F-WntX, in sham hearts, which persists after MI. The related F-Trans is an intermediary population between F-SL and F-WntX (Figure 9). Aside from a low proportion of activated fibroblasts (F-Act) present in sham hearts, no other sham population (>75% of GFP+ cells) showed an activated phenotype. When we re-analyzed the scRNA-seq data of Skelly et al. on interstitial cells from uninjured hearts (Skelly et al., 2018), we identified all of the main fibroblast populations that we describe here in sham hearts (Figure 4—figure supplement 5A–C). F-Act and F-WntX expressed activation marker Postn in both studies; however, in contrast to our study, all populations identified by Skelly et al., including endothelial and immune cells, expressed the contractile marker Acta2. The reason for this is unclear, but is likely technical. Gladka et al. profiled cardiac populations after ischemia-reperfusion injury using scRNA-seq and highlighted Ckap4 as a novel marker of activated fibroblasts (Gladka et al., 2018); however, our data shows Ckap4 expression across virtually all cardiac stromal populations (Figure 4—figure supplement 5D), a discrepancy that may relate to the relatively low number of cells profiled in the Gladka et al. study.

Figure 9. Schematic summary of the flux and pseudotime differentiation dynamics of GFP+ populations between sham, MI-day 3 and MI-day 7.

Populations are ordered in pseudotime from unactivated (top) to most activated/mature (bottom). Arrows connecting populations indicate direction of proposed differentiation/pseudotime trajectory. Colored arrows indicate whether the population appears to expand or diminish relative to the previous time-point.

Among fibroblasts, F-WntX uniquely expressed Wif1, encoding a canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling antagonist (Meyer et al., 2017; Bányai et al., 2012). WNT pathways play complex roles in cardiac biology and disease, impacting immune, vascular and pro-fibrotic pathways, and many drugs inhibiting WNT signaling are under investigation for their impacts on heart repair (Foulquier et al., 2018; Palevski et al., 2017). WIF1 additionally inhibits signaling through CTGF, a polyfunctional matricellular protein and positive driver of fibrosis (Travers et al., 2016; Surmann-Schmitt et al., 2012). WIF1 is a tumor suppressor inhibiting tumour angiogenesis through both WNT and VEGF pathways (Ko et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2009). Wif1 knockout mice show inhibition of Mo differentiation and abnormal chamber remodeling after MI (Meyer et al., 2017), while un-regulated transgenic WIF1 expression causes dilated cardiomyopathy (Lu et al., 2013), collectively indicating that correctly regulated WIF1 positively contributes to cardiac repair. One source of WNT proteins is inflammatory macrophages, and myeloid-specific deletion of the essential WNT transporter Wntless leads to improved cardiac functional recovery after MI involving an increase in reparative M2-like macrophages and angiogenesis (Palevski et al., 2017). In addition to WIF1, F-WntX cells showed upregulation of other WNT and TGFβ pathway antagonists (Figure 5A), overall flagging F-WntX cells as paracrine mediators of an anti-WNT/CTGF/TGFβ signaling milieu essential for cardiac repair.

WIF1 protein expression occurred in the border zone at MI-day 3, but not in sham or MI-days 1 and 7 hearts, consistent with previous findings (Meyer et al., 2017). We also detected WIF1 in ~4% of CD45+ immune cells infiltrating the border zone. We acknowledge that our IF studies may have underestimated the number of WIF1+ cells; for example, if we were unable to detect cells actively secreting WIF1 but lacking protein accumulation in the golgi. Contrary to our results, Meyer et al. showed WIF1 levels peaking at MI-day 1 and diminished by MI-day 7 using western blotting (Meyer et al., 2017). Whereas these differences need resolving, en face our data suggest that WIF1 expression is post-transcriptionally regulated with a peak around MI-day 3, consistent with our proposed function for WIF1 and the F-WntX population generally in inhibiting fibrosis and angiogenesis, and promoting differentiation of Mo, during the transition between the inflammatory and fibrotic phases of heart repair.

At MI-day 3, both F-SH and F-SL were significantly diminished, and we hypothesize that this occurs as they convert to an activated state (F-Act; Postn+Acta2negative-low). The scale of conversion suggests that fibroblasts remote from the infarct also become activated. Whereas F-Act upregulated genes that were associated with collagen fibrils and wound healing in common with MYO, F-Act cells are by far more closely related to resident fibroblasts than to MYO. A proportion of F-Act cells were actively proliferating at MI-day 3 and to a lesser extent at MI-day 7, consistent with the known peak of fibroblast proliferataion (Fu et al., 2018; Ivey et al., 2018). At MI-day 3, we also identified an activated, non-proliferating fibroblast population (F-CI) situated between F-Act and F-Cyc in trajectory plots, showing strong upregulation of genes supporting protein translation, and we hypothesize that this secondary activated state occurs in readiness for cell division and differentiation.

MYO was evident only at MI-day 7, where they represented >50% of total GFP+ cells. This may be an underestimate, as the Chromium microfluidic device biases against larger cells, and some MYO cells may be GFP-. Highlighting the limitations of using the contractile marker αSMA to define MYO (Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017), a proportion of F-WntX, F-Act, F-Cyc and MYO cells expressed its gene, Acta2. MYO cells massively upregulated a distinct network of genes related to cell adhesion, collagen fibril organization and angiogenesis, consistent with their known roles (Shannon et al., 2003; Tallquist and Molkentin, 2017). Top ECM genes in these categories such as Postn, Fn1 and Col8a1 were expressed in virtually all MYO cells. However, our stage specific analysis of GFP+ cells at MI-day 7 allowed us to discern three distinct MYO sub-populations expressing pro-fibrotic (MYO-2 and MYO-3) or anti-fibrotic (MYO-1) states. MYO-1 expressed anti-TGF-β, anti-WNT and anti-proliferative signatures. Consistent with the view that MYO differentiation involves multiple cellular states, Fu et al. (2018) recently described a population of fibrobast-derived 'matrifibrocytes', quiescent cells which persist in the mature scar after MI.

The three major trajectories predicted by our Diffusion Map pseudotime analysis offer new insights into cardiac homeostasis and repair. The directionality of trajectories is suggested by the fact that all appear rooted in the resident F-SH and F-SL fibroblasts. One major trajectory arises specifically from F-SL and transits through F-Trans to F-WntX as the terminal state (Figure 9). Neither F-Trans nor F-WntX proliferate and may be primed for involvement in an injury response without the need for expansion. Up to MI-day 3, F-Act cells proliferate, but do not differentiate to MYO, showing that these events can be uncoupled. Differentiation to MYO occurs after MI-day 3, and our trajectory data suggest that this is largely from non-proliferating F-Act cells. We found no evidence for significant proliferation of MYO, although earlier time points need to be analyzed.

Resident fibroblasts F-SH and F-SL were depleted at MI-day 3, likely as a result of their activation and proliferation, and showed an apparent restoration by MI-day 7 in both TIP and GFP+ cells (falling just short of our stringent p-value of 0.01 for DPA) (Figure 1A,E; Figure 4A,D; Figure 8A,B). A caveat of pseudotime trajectories is that they may be bi-directional. If confirmed, the restoration of F-SH and F-SL between MI-days 3–7 (after the main fibroblast proliferative period [Fu et al., 2018; Ivey et al., 2018]) points to renewal involving phenotypic regression. Regression of myofibroblasts to a less activated state was proposed recently (Kanisicak et al., 2016), although our data suggest that the Postn-Cre lineage tracing mice used in that study to mark myofibroblasts labels most if not all F-Act cells (Figure 4E). Certainly, the mechanism of activation, proliferation, self-renewal, differentiation and de-differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts warrants deeper investigation.

The Mo/MΦ lineages of the heart have diverse functions, including in immunity, removal of debris and protection against autoimmunity during the early phases of MI, while promoting repair in latter phases, remodeling of the fetal coronary tree, neonatal heart regeneration and atrioventricular conduction (Lavine et al., 2014; Hulsmans et al., 2017; Leid et al., 2016; Aurora et al., 2014; Nahrendorf et al., 2007). The adult heart, like other organs, contains resident MΦ, some of which have their origins in erythromyeloid progenitors in the embryonic yolk sac and fetal liver (Leid et al., 2016) and which self-renew during homeostasis and injury (Heidt et al., 2014; Epelman et al., 2014; Dick et al., 2019). Other resident populations have differing degrees of monocyte dependence and some may eventually be supplanted during injury and aging by blood-born monocytes (Molawi et al., 2014; Dick et al., 2019). These resident MΦ likely have roles in defense against infection, antigen presentation and stimulation of T-cell responses, as well as efferocytosis (Epelman et al., 2014). In the neonatal heart, they are though to be essential for regeneration through stimulation of CM proliferation and angiogenesis (Lavine et al., 2014), and in the adult may be important for limiting fibrosis (Lavine et al., 2014; Dick et al., 2019), functions similar to pro-reparative M2 MΦ.

Our scRNA-seq data identified most of the known Mo/MΦ populations highlighted by targeted scRNA-seq of cardiac Mo/MΦ cells (Dick et al., 2019), including Ccr2+ and Ccr2- tissue resident MΦ, pro-inflammatory M1 Mo and MΦ at MI-day 3, and non-classical M2 MΦ at MI-day 7, as well as several minor populations and inflammatory fibroblasts. These data, combined with communication maps, provide a preliminary framework for further analysis of their relationships and flux in homeostasis, different disease models and after therapeutic interventions. Our Diffusion Maps lineage trajectory shows a continuum of states from M1Mo through M1MΦ to M2MΦ across the injury response, consistent with the recognised plasticity of blood born Mo (Lavine et al., 2018; Nahrendorf and Swirski, 2016). However, whether these states are determined exclusively within the injury environment remains to be determined. Our trajectory also shows convergence of M2MΦ with tissue-resident MΦ (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C). An emerging theme in the field is the similarity between yolk sac-derived tissue-resident MΦ and subsets of blood-born MΦ that appear during the reparative phase of MI (Dick et al., 2019). However, the latter may not fully adopt the gene expression signature of resident cells, nor fully compensate for their proposed functions, as suggested in the context of genetic ablation of Cc3cr1+ tissue-resident MΦ, although this may relate to the timing of their deployment (Dick et al., 2019). Irrespective of whether such cells are identical, it is noteworthy that pro-repairative macrophages appear to have multiple developmental origins, as found for virtually all other major adult heart lineages including CMs, ECs, SMCs, fibroblasts and adipocytes.

Our scRNA-seq data can be mined for expression of genes implicated in other forms of heart disease. For example, of 167 genes proximal to single nucleotide polymorphisms implicated in GWAS studies in atrial fibrillation (AF) (Roselli et al., 2018), 119 (71%) showed expression in our TIP single-cell data (for examples see Figure 1—figure supplement 8), suggesting possible involvement of stromal cells in AF risk.

We have identified substantial non-linear dynamics in the interactive cell communities of the heart (Figure 9), which, in this new light, can be further analyzed with lineage and functional tools. There remains a compelling clinical and economic rationale for finding new therapies for controlling the inflammation and fibrosis that accompanies virtually all forms of adult heart disease (Gourdie et al., 2016). In the long term, scRNA-seq analysis of cardiac homeostasis and disease will provide new entry points for discovering novel drugs and interventions supporting heart repair and regeneration.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (Mus musculus) | Pdgfra | NCBI | NCBI Gene ID: 18595, MGI:97530 |

|

| Strain, strain background (Musmusculus, C57BL/6J) |

Wild type, WT | The Jackson Laboratory, Stock Number: 000664, |

RRID:IMSR:JAX:000664

|

|

| Strain, strain background (Musmusculus, C57BL/6J) |

Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor; PDGFRaGFP/+ | The Jackson Laboratory, Stock Number: 007669, PMID: 12748302 |

MGI:2663656 | |

| Antibody | APC-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse PDGFRa (CD140a) |

eBioscience | 17-1401-81, Clone APA5 |

(1:200) |

| Antibody | PE-Cy7-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1) |

eBioscience | 25-0311-82, Clone 390 |

(1:400) |

| Antibody | PE-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse Sca1 (Ly6A/E) |

BD Pharmingen | 553108, Clone D7 |

(1:400) |

| Antibody | APC-Cy7-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD45 |

BD Pharmingen | 557659, Clone 30-F11 |

(1:400) |

| Antibody | PE-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse F4/80 |

eBioscience | 12-4801-82, Clone BM8 |

(1:400) |

| Antibody | APC-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD206 (MMR) Antibody |

BioLegend | 141708, Clone C068C2 |

(1:200) |

| Antibody | Chicken polyclonal anti-GFP |

Abcam | ab13970 | (1:200) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-Wif1 |

Abcam | ab186845 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Rat monoclonal anti-CD31 |

Dianova | DIA-310, Clone SZ31 |

(1:100) |

| Antibody | Rat monoclonal anti-CD45 |

BD Biosciences | 553076, Clone 30-F11 |

(1:100) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-aSMA |

Sigma | A2547, Clone 1A4 |

(1:100) |

| Antibody | Rat monoclonal anti-Ki67 |

Dako | M7249, Clone TEC-3 |

(1:100) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 |

BD Biosciences | 610822, Clone 35/GM130 |

(1:400) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Chicken Alexa 488 |

Life Technologies | A11039 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rabbit Alexa 555 |

Life Technologies | A21429 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rabbit Alexa 680 |

Life Technologies | A21109 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-Rat Alexa 555 |

Life Technologies | A21434 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | Donkey polyclonal anti-Mouse Alexa 594 |

Life Technologies | A21203 | (1:500) |

| Antibody | APC-conjugated Rat monoclonal anti-mouse PDGFRa (CD140a) |

eBioscience | 17-1401-81, Clone APA5 |

(1:200) |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Chromium Single Cell 30 Library and Gel Bead Kit v2 |

10x Genomics | 120237 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Chromium Single Cell A Chip Kit |

10x Genomics | 120236 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Chromium i7 Multiplex Kit | 10x Genomics | 120262 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit (96 Samples) |

Illumina | FC-131–1096 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Nextera XT Index Kit v2 | Illumina | FC-131–2001 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

Fluidigm Single-Cell Auto Prep IFC chip (5–10 um) |

Fluidigm | 100–5759 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for the Fluidigm C1 System |

Takara | 635026 | |

| Commercial assay or kit |

NextSeq 500/550 High Output Kit v2 |

Illumina | FC-404–2002 | |

| Other | LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytoxicity Kit, for mammalian cells |

Thermo Fisher Scientific |

L-3224 | |

| Software, algorithm | CellRanger | 10x Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/downloads/latest | |

| Software, algorithm | STAR | PMID: 23104886 |

https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR; RRID: SCR_015899 |

|

| Software, algorithm | Bowtie 2 | PMID: 22388286 |

http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml; RRID:SCR_005476 |

|

| Software, algorithm | featureCounts | PMID: 24227677 |

http://subread.sourceforge.net; RRID:SCR_012919 |

|

| Software, algorithm | Seurat | PMID: 29608179 |

https://satijalab.org/seurat/; RRID: SCR_007322 |

|

| Software, algorithm | Destiny | PMID: 26668002 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/destiny.html | |

| Software, algorithm | PANTHER | PMID: 27899595 |

http://www.pantherdb.org; RRID:SCR_004869 |

|

| Software, algorithm | Iterative Random Forest | PMID: 29351989 | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/iRF/index.html | |

| Software, algorithm | Differential Proportion Analysis |

This paper | Source code 1 | Materials and methods: Differential proportion analysis |

| Software, algorithm | Cell communication analysis |

This paper | Source code 1 | Materials and methods: Ligand-receptor networks |

Murine model

8-12 weeks old male mice were used in all experiments unless otherwise stated. For the single-cell RNA sequencing experiment, mice had a H2B-eGFP fusion gene knock-in at the endogenous Pdgfra locus (Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor; PdfgraGFP/+).

Surgically induced myocardial infarction

To induce acute MI, mice were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a combination of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg), and intubated. Hearts were exposed via a left intercostal incision followed by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Sham operated mice underwent surgical incision without ligation. Hearts were harvested for paraffin-embedding, or FACS analysis at 3 or 7 days post-surgery, as indicated in Results.

FACS experiments

TIP were isolated as previously described (Chong et al., 2011). Briefly, hearts were minced and incubated in collagenase type II (Worthington, USA) at 37°C before filtering through 40 μm strainers. Cells were resuspended in red cell lysis buffer, followed by dead cell removal, immunostaining for 15 min on ice with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies and two times wash with FACS buffer (1x PBS containing 2% fetal bovin serum) before acquisition.

We employed very stringent gating strategies to exclude doublets in the FACS analysis: FSC-H vs FSC-A, FSC-H vs FSC-W and SSC-H vs SSC-W cytograms were used to discriminate and gate out doublets/cell aggregates during sorting or from the analysis (Figure 1—figure supplement 5). To account for the autofluorescence generated by MI, we used a wild-type MI mouse as control to set up the gating strategy (Figure 1—figure supplement 6).

For the TIP fraction, total DAPI-negative live single cells were sorted in FACS buffer. For the GFP+ fraction, GFP+CD31-cells were sorted from the DAPI-negative live single cells. For Fluidigm experiments, SCA1+PDGFRα+CD31-(S+P+) cells were isolated and sorted as described above. For each sample, at least 10,000 final gate events were collected and stored for the later analyses.

Colony formation assay

TIP cells were isolated as described and stained with indicated antibodies. FACS sorted primary cells were seeded at a clonogenic density of 50 cells/cm2 (500 cells per well of 6-well plate) and were cultured in α-Minimal Essential Medium (α-MEM) containing 20% FBS+1% Pen/Strep at 37°C in a humidified 2% O2 and 5% CO2 incubator, with medium changes every 2–3 days. After 8-day culture, colonies were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained with 0.05% (v/v) crystal violet dye in water. Differences in colony number and size were evaluated by a two-tailed one-sample t-test to test for variability between individual samples.

Sectioning, immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

Paraffin sections