Abstract

This review integrates evidence on community mobilisation (CM) for maternal and child health in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) to identify the impact on empowerment. For the purposes of this review we use the following definition of CM: “a capacity-building process through which community members, groups, or organizations plan, carry out, and evaluate activities on a participatory and sustained basis to improve their health and other conditions, either on their own initiative or stimulated by others,” (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007, pp. 5). A scoping review was chosen to conduct a search and analysis of the literature due to the broad, complex nature of the topic. The search yielded 136 articles, and 19 met the inclusion criteria. This review illustrates CM as an important research process for engaging the community, ensuring that interventions are meeting the needs of the community, take context into account, and are sustainable. Community mobilisation was associated with positive behaviour change and/or health outcomes. However, community mobilisation was not defined or operationalised consistently among the identified studies. Empowerment was also not defined, measured, or reported on in the articles. This review provides recommendations for the reporting of CM and its influence on empowerment in communities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: community mobilisation, community mobilization, maternal & child health, sub-Saharan Africa, empowerment

Background

Approximately 800 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth with 99% of deaths occurring in developing countries (World Health Organization, [WHO], 2016). With global efforts, maternal mortality has decreased by almost 50% over the past thirty years (WHO, 2016). Despite progress in the reduction of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), this region continues to shoulder 66% of the global estimates for maternal mortality, remaining one of the top two regions that account for the majority of maternal deaths globally (WHO, 2015). Similarly, children under the age of five in SSA are fifteen times more likely to die before they reach the age of five than those from high income countries, with the highest risk of death occurring during the neonatal period (WHO, 2017). Health outcomes for women and children are closely linked, with research indicating that skilled care prior to, during, and at the time of delivery can contribute to preventing deaths (WHO, 2016).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) prioritize health and the promotion of well-being for individuals at all ages, particularly through goal number three (United Nations, 2017). Target 3.2 of this goal specifically calls for a reduction in maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 and an end to all preventable deaths of newborns and children under five (WHO, 2015). There are complex intersecting political, economic, and socio-cultural realities that directly influence maternal mortality, especially among marginalized groups (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007). High maternal mortality directly impacts the health of neonates and under five children, and both categories of loss are influenced by socio-cultural, economic, political, geographical, and historical factors. It is essential that solutions seeking to address these complex, global concerns investigate the socio-environmental realities that directly influence health outcomes, expanding and drawing on local competencies.

To address these global health inequities and adhere to the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, which urged for the protection and promotion of the health of all people, it is essential that maternal and child health interventions involve a community-focused approach (WHO, n.d.). Community mobilisation (CM) is a capacity building strategy anchored in the process of empowerment that has been used in low-and-middle income countries (LMIC) to improve maternal and child health with great success, addressing and impacting direct health outcomes as well as the social and behavioral determinants that influence them (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007). This strategy has evolved from earlier conceptions of community involvement structured as a passive recipient model in which the researcher took the role of educator to a more engaging strategy during which the researcher takes the role of facilitator. This newer conceptualization focuses on fostering capabilities in individuals and communities to identify and solve problems, as well as to realize their potential to collectively act to change the conditions of their lives (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007). Community mobilisation interventions are impactful and require a strong commitment to what is a long term (generally at least three year), multifaceted process with many strategies occurring simultaneously.

There is no accepted universal definition of CM, as it is of crucial importance that the intervention is tailored to fit the local context in which it is situated. However, for this scoping review, we understood CM as outlined in the following definition, “a capacity-building process through which community members, groups, or organizations plan, carry out, and evaluate activities on a participatory and sustained basis to improve their health and other conditions, either on their own initiative or stimulated by others,” (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007, pp. 5). Community mobilisation interventions relying on this or a variation of this definition frequently employ what is known as the Community Action Cycle or a variation therein, a dynamic process that leads the community from identification of problems, towards collectivization to solve them, and finally to ownership of the process (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007).

Community mobilisation’s impact on health outcomes are thought to be catalyzed and sustained through transformations in the socio-cultural, political, economic environment as a direct result of individual and community empowerment (Howard-Grabman et al., 2007). Empowerment presents an equal challenge to define as it must be situated contextually, can be conceptualized as a process or an outcome, and has been measured by different disciplines in a variety of ways (Malhotra, Schuler & Boender, 2002). Despite great success with CM interventions around reducing morbidity and mortality for women and children, it has been a challenge to capture a holistic understanding of these benefits and others due to the multi-faceted nature of CM interventions (Altman et al., 2015). Although it may prove difficult to parse out each component of a CM intervention; defining, measuring, and assessing the impact of empowerment would provide valuable insight.

The CM intervention is built on a premise that through the process of empowerment, the social and behavioral determinants of health will be transformed, resulting in improved outcomes. The facilitation of dialogue and interaction between various actors in a community arguably has additional power in promoting person centered care. However, at this time there is a gap in the literature reporting on the link between CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA and empowerment. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review is to gain an understanding of how CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA impact the empowerment of individuals.

Methods

A scoping review was chosen to conduct a search and analysis of the literature due to the broad and complex nature of investigating how CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA impact the empowerment of the individuals and/or communities involved. The five stages of a scoping review outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) were followed, which include: identifying research questions, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and summarizing and reporting results.

Inclusion Criteria

Articles were included in the review if they were focused on CM interventions for maternal and/or child health in countries within sub-Saharan Africa. Given the evolving nature of the approach towards CM interventions the search included only articles published between 1997–2017 to avoid inclusion of articles focused on an archaic definition of CM. Articles were only included if CM was a component of the study. Finally, articles were eligible for inclusion only if they were data driven and published in English in peer-reviewed journals.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that focused on CM for infectious diseases unrelated to maternal and child health were excluded from the review, as were those that referenced but did not use CM. There were five systematic reviews that included countries outside of sub-Saharan Africa that were not included in the review. Articles that only recommended CM as a strategy in their concluding remarks as well as articles focused on facility-only CM interventions with no community aspect were also excluded.

Search Strategy

Three electronic databases were searched: PubMed (biomedical literature), Global Health (public health literature, including journals from LMIC), and Scopus (international literature). The search was an iterative process and took place from September 19, 2017 through November 14, 2017. The search began in PubMed using MESH terms, followed by Global Health using subject headings, and finally in Scopus. Search terms for CM across all three databases included: “community mobilization” or “community mobilisation” or “ social accountability approach” or “participatory action cycle”. Terms for SSA combined with the CM terms using “and” included: Africa South of the Sahara, sub-Saharan, or Subsaharan. For Global Health and Scopus, these SSA terms were included as well as a full list of the 43 countries defined by the Library of Congress as SSA (Library of Congress, 2010). There were many terms used in searching for both empowerment as well as maternal and/or child health. See Table 1 for a full list of search terms in each database.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| Database | Community Mobilisation Terms |

AND sub-Saharan Africa Terms |

AND Maternal and Neonatal Mortality Terms |

AND Empowerment Terms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | “Community mobilization” OR “community mobilisation” OR “social accountability approach” OR “participatory action cycle” | “Africa South of the Sahara”[Mesh] OR “Sub-Saharan”[tiab] OR Subsaharan[tiab] | “Pregnant Women”[Mesh] OR “Pregnancy”[Mesh] OR “Midwifery”[Mesh] OR “Nurse Midwives”[Mesh] OR “Maternal Health”[Mesh] OR “Maternal Health Services”[Mesh] OR “Reproductive Health”[Mesh] OR “Reproductive Health Services”[Mesh] OR “Maternal Welfare”[Mesh] OR Perinatal[tiab] OR Postnatal[tiab] OR Preconception[tiab] OR Prenatal[tiab] OR maternal[tiab] OR “sexual health”[tiab] OR midwife[tiab] OR midwifery[tiab] OR “traditional birth attendants” OR pregnancy[tiab] OR pregnant[tiab] OR reproductive [tiab] OR “family planning”[tiab] OR birth[tiab] OR puerperium [tiab] | “empowerment” OR “agency” OR “options” OR “choice” OR “control” OR “power” OR “female autonomy” OR “domestic economic power” OR “gender equity” OR “gender equality” OR “gender stratification” OR “gender discrimination” |

| GlobalHealth | “Community mobilization” OR “community mobilisation” OR “social accountability approach” OR “participatory action cycle” | DE “Africa South of Sahara” OR DE “Central Africa” OR DE “East Africa” OR DE “Sahel” OR DE “Southern Africa” OR DE “West Africa” OR TI (“Sub-Saharan” OR Subsaharan OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Gabon OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR “South Africa” OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR Benin OR “Burkina Faso” OR Cape Verde OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Togo ) OR AB (“Sub-Saharan” OR Subsaharan OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Gabon OR Burundi OR Djibouti OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Kenya OR Rwanda OR Somalia OR Sudan OR Tanzania OR Uganda OR Angola OR Botswana OR Lesotho OR Malawi OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR “South Africa” OR Swaziland OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe OR Benin OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Cote d’Ivoire” OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guinea OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR Liberia OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR Togo) | DE “Pregnant Women” OR “maternal health” OR “reproductive health services” OR TI( “ “pregnancy” OR DE “sexual reproduction” OR DE “birth” OR DE “eclampsia” OR DE “maternal nutrition” OR DE “maternal recognition” OR DE “pregnancy complications” OR DE “pregnant adolescents” DE “midwives” OR DE “parturition” DE “maternal mortality” OR DE “maternity” OR DE “maternity services” DE “perinatal mortality” (DE “perinatal mortality” OR DE “postnatal development” OR DE “postpartum interval” OR DE “postpartum period” OR DE “puerperium” DE “prenatal development” OR DE “prenatal education” OR DE “prenatal period” OR DE “prenatal screening” OR DE “prepartum period” OR DE “sexual behaviour” OR DE “sexually transmitted diseases” OR DE “sexual contacts” OR DE “sexual partners” OR DE “sexual roles” OR DE “gender relations” OR DE “role conflicts” OR DE “roles” OR DE “women” OR DE “contraceptives” OR DE “condoms” OR DE “contraception” OR AB “pregnancy” OR DE “sexual reproduction” OR DE “birth” OR DE “eclampsia” OR DE “maternal nutrition” OR DE “maternal recognition” OR DE “pregnancy complications” OR DE “pregnant adolescents” DE “midwives” OR DE “parturition” DE “maternal mortality” OR DE “maternity” OR DE “maternity services” DE “perinatal mortality” DE “perinatal mortality” OR DE “postnatal development” OR DE “postpartum interval” OR DE “postpartum period” OR DE “puerperium” DE “prenatal development” OR DE “prenatal education” OR DE “prenatal period” OR DE “prenatal screening” OR DE “prepartum period” OR DE “sexual behaviour” OR DE “sexually transmitted diseases” | “empowerment” OR “agency” OR “options” OR “choice” OR “control” OR “power” OR “female autonomy” OR “domestic economic power” OR “gender equity” OR “gender equality” OR “gender stratification” OR “gender discrimination” |

| Scopus | “Community mobilization” OR “community mobilisation” OR “social accountability approach” OR “participatory action cycle” | “sub saharan africa” OR “Angola” OR “Benin” OR “Botswana” OR “Burkina Faso” OR “Burundi” OR “Cameroon” OR “Cape Verde” OR “Central African Republic” OR “Chad” OR “Comoros” OR “Congo Brazzaville” OR “Côte d’Ivoire” OR “Djibouti” OR “Guinea” OR “Eritrea” OR “Ethiopia” OR “Gabon” OR “The Gambia” OR “Ghana” OR “Guinea” OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR “Kenya” OR “Lesotho” OR “Liberia” OR “Madagascar” OR “Malawi” OR “Mali” OR “Mauritania” OR “Mauritius” OR “Mozambique” OR “Namibia” OR “Niger” OR “Nigeria” OR “Rwanda” OR “Sao Tome and Principe” OR “Senegal” OR “Seychelles” OR “Sierra Leone” OR “Somalia” OR “South Africa” OR “Sudan” OR “Swaziland” OR “Tanzania” OR “Togo” OR “Uganda” OR “Western Sahara” OR “Zambia” OR “Zimbabwe” | “maternal health” OR “sexual health” OR “reproductive health” OR “maternal child health” OR “maternal mortality” OR “maternal morbidity” OR “ midwife” OR “newborn” OR “neonat*” OR “prenatal care” OR “antenatal care” OR “postnatal care” OR “abortion” OR “family planning” OR “contraceptive*” OR “pregnancy outcome” | “empowerment” OR “agency” OR “options” OR “choice” OR “control” OR “power” OR “female autonomy” OR “domestic economic power” OR “gender equity” OR “gender equality” OR “gender stratification” OR “gender discrimination” |

Data Extraction

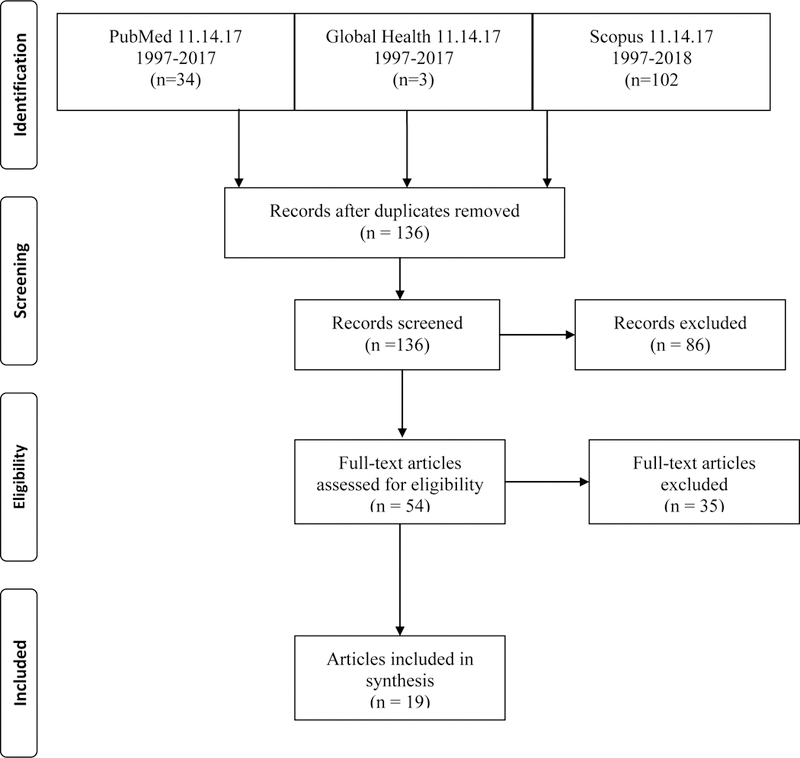

Articles were exported to Refworks for organization prior to analysis where duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved from these databases (n=136) were reviewed to assess their adherence to the population, intervention, and region of interest. There were a total of 34 articles retrieved from PubMed, 3 from Global Health and 102 from Scopus. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied during a title and abstract screen. The remaining 54 articles were evaluated through a full text review guided by the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process produced a total of 19 articles to be included in the final review and synthesis, as depicted in the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA1 diagram

1From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Iteçms for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Results

There were 19 articles included in the final review, with publication dates ranging from 2001 through 2017 (see Table 2 for the Summary and Operationalization of CM Table). Studies were conducted in 8 of the 43 countries in SSA. Studies included the following countries: Kenya (n=1), Cameroon (n=1), Guinea Bissau (n=1), Madagascar (n=1), Liberia (n=1), Uganda (n=1), Nigeria (n=3), and Malawi (n=6). Multiple studies emerged from Nigeria and Malawi, where the data from large projects were evaluated through multiple lens. Study designs represented in the final sample included: cluster randomized design (n=6), quasi experimental (n=4), cohort (n=3), cross sectional surveys (n=2), systematic reviews (n=2), secondary analysis (n=1), and pre-post study design (n=1).

Table 2.

Operationalization of Community Mobilisation & Effectiveness of Strategy

| Authors & Year | Study Aims | Design Characteristics |

Operationalization of CM | Effectiveness of Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babalola et al. (2006) | Impact of CM on female genital cutting (FGC) | Cohort study (n=951 baseline, n=971 endline) that took place in Nigeria over 12 months | • Community Action Cycle | • Mass media campaign in addition to CM had most impact • State with higher percentage of women who had undergone FGC at baseline showed less change in ideational factors following CM • Results used to inform policy abolishing FGC |

| Babalola et al. (2001) | Impact of CM project for reproductive health | Cohort study (n-803 baseline, n=856 endline) that took place in Cameroon over 12 months | • Adaptation of Community Action Cycle | • Differences in exposure & participation across sites and age groups • Increases in use of clinic based health services, modern FP. Higher impact seen in one of the districts in comparison to the other. • Commitment of community mobilisers waned in between supervisory visits as evidenced by indicators of FP use. |

| Boone et al. (2016) | Assess decrease in <5 mortality & maternal mortality post-CM intervention. | Cluster randomized design, cohort study (n=6,729 intervention, n=6,894 control) that took place in Guinea Bissau over 3 years. | • Community health clubs formed, facilitated by trained health promoters • Clubs met 3x per month for the first 6 months, then once per month thereafter • Villages selected 1 community health-worker and one traditional birth attendant per 20–50 homes. |

• CM programs in areas with weak health service infra-structure may not be strong enough to reduce under five mortality • Intervention group had decreased maternal deaths • Under 5 mortality did not decrease. • Caregivers in intervention group had improved knowledge and care seeking behavior. |

| Colbourn et al. (2013) | Quality improvement of health facility, reduction in <5 mortality, and maternal/perinatal mortality through CM. | Cluster randomized controlled trial (n=729) that took place in Malawi over 3 years. | • Community Action Cycle • Plan Do Study Act quality improvement at health centres & hospitals |

• CM + quality improvement reduced neonatal mortality by 22% • CM alone reduced perinatal mortality by 16% • No impact on maternal mortality. • Quality improvement areas with no CM component did not reduce neonatal, perinatal, or maternal mortality |

| Colbourn et al. (2015) | Evaluate cost-effectiveness of CM | Secondary analysis that took place in Malawi over 3 years | • Community Action Cycle • Plan Do Study Act quality improvement at health centres & hospitals |

• Community intervention more effective and less expensive than facility intervention. • Community intervention combined with facility intervention most cost effective. |

| Ejembi et al. (2014) | Determine distribution, acceptability, and uptake of misoprostol sustainability at the community level. | Quasi-experimental design (n=1,577 postpartum interviews) in Nigeria over 12 months. | • Community dialogues • Community oriented resource persons, community drug keepers, and traditional birth attendants identified & trained as result of community dialogues |

• Distribution of misoprostol in community is feasible, safe. • Women who took misoprostol reported taking it at the right time (97%) and correct dose (87%) • Project results informed health policy in Nigeria, then scaled up across the country. |

| Ekirapa Kiracho et al. (2017) | Community mobilization and empowerment to stimulate demand for services, health provider/management capacity building component to strengthen delivery of quality care. | Quasi-experimental design (n=2,237 baseline, n=1,946 endline) that took place in Uganda over 3 years. | • Susman’s Participatory action research methodology | • Increase in antenatal care (ANC visits, increased fourth ANC visits, increased facility delivery, and safer newborn care practices. • Women in intervention area visited by community health workers 49% more likely to attend ANC in first trimester. • Facility deliveries predicted by four ANC visits and savings for maternal health/birth preparedness. |

| Gullo et al. (2017) | Test effectiveness of CM on reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. Evaluated perceived service quality, health behavior, and supportive care outcomes. | Cluster randomized controlled design (n=1,301 baseline, n=1,300 endline) that took place in Malawi over two years. | • Adaptation of Community Action Cycle to include facilities (social accountability approach) • CARE’s Community Score Card |

• Improved support for community health workers (CHW). • Improved relationships between CHW and community • Increased CHW visits to pregnant women • Women’s satisfaction with reproductive health services increased |

| Guyon et al. (2009) | Assess CM intervention impact on infant and young child feeding practices, uptake of micronutrient supplements, and women’s dietary practices. | Pre and post quasi-experimental design (n=1,200 baseline, n=1,760 endline) that took place in Madagascar over 9 years for the intervention (5 years of data collection). | • Policy & partnerships • Capacity building • Community support • Behavior change communication |

• Increase in breastfeeding post intervention • Cost effective |

| Lori et al. (2013) | Impact of CM for maternity waiting homes (MWHs) to increase use of skilled birth attendants (SBAs), and the possibility for traditional midwives to work as team with SBAs. Study assessed perceptions of this working relationship between SBAs and traditional midwives and if MWHs decrease maternal and child morbidity and mortality. | Cohort study that took place in 10 rural primary health facilities (5 with MWHs) over 17 months in Liberia. Quantitative data was collected from MWH logbooks (n=500) and qualitative data was gathered from interviews (n=46). | • Community Action Cycle | • Communities with a maternity waiting home (MWH) had lower rates of maternal/perinatal death. • Increase in team births in both MWH and non-MWH sites. • MWH included in Liberia’s accelerated action plan to reduce neonatal and maternal mortality. |

| Mburu et al. (2012) | Present the results of community mobilization model implemented by International HIV/AIDS Alliance. | Secondary analysis (n=750 people, n=120 clusters) that took place in Uganda over two years. | • Facilitating networks for community based education and referrals • Training for peer to peer support • Capacity building |

• Networks of peer support for people living with HIV are effective in mobilizing communities to prevent HIV transmission. • Sharing data between community groups and facilities is necessary to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV. • CM is sustainable through income generating activities. Linking CM activities to facilities will increase sustainability. |

| Mseu et al. (2014) | Evaluate knowledge and practices of childbearing women on key practices within Safe Motherhood project administered by Necheu District Health Office. | Cross sectional descriptive design (n=400, n=134 women’s groups initiated) that took place in Malawi over six years. | • Adaptation of Community Action Cycle | • Increase in ANC visits. • Increased awareness of need for ANC and breastfeeding but lack of retention of information. • Cultural myths impacted individual action despite awareness of need for ANC. |

| Muzyamba et al. (2017) | Systematic review of empirical evidence of community mobilization in sub-Saharan Africa and impact on HIV positive women. | Systematic review that included 14 publications on role of CM provision in maternal care in sub-Saharan Africa using experimental designs published between 1990–2015. | • Operationalization should include: • reliance on peer support • use of indigenous resources in maternal care provision • collaboration between community & professionals in designing maternal care initiatives |

• There is a sound base of empirical evidence supporting the use of CM for HIV negative women. • Empirical evidence on causal link between CM and it is missing for HIV positive women. |

| Prata et al. (2012) | Assess importance of community mobilization in the uptake of health intervention which included the community-based distribution of misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. | Pre- and post-study design (n=21,000 in community, n=1,875 women who participated, n=1,800 postpartum interviews, n=2,520 attended community dialogue sessions) that took place in Nigeria over 11 months. | • Community dialogues • Community education and information sessions • Community oriented resource persons, community drug keepers, and traditional birth attendants identified & trained |

• CM messages reached 80–90% of women, with high rates of retention post intervention. • Informed national guidelines, misoprostol added to Nigeria’s Essential Medicines list during study period. |

| Rosato et al. (2012) | Understand strategies developed by women’s groups through CM and their impact. | Factoral cluster randomized controlled design (n=197 surveyed, n=12,000 attended 184 community groups) that took place in Malawi over five years. | • Community Action Cycle | • Average number of strategies implemented per group was eight, which made it difficult to disaggregate effectiveness of individual strategies. • A wide range of diverse strategies were implemented in each community reaching a large population. Implementation and resources were community generated and driven. |

| Undie et al. (2014) | Impact of community mobilization (CM) on increasing awareness and use of post abortion care and family planning (FP) | Pre and post quasi-experimental design with 6 clusters (1cluster = 5 or more villages) that took place in Kenya over 18 months | • Community Action Cycle | • Increased proportion of women who reported early pregnancy bleeding. • Raised awareness of FP methods and early pregnancy bleeding, but did not demonstrate an increased use of FP methods. |

| Wagman et al. (2015) | Assess the effect on past-year intimate partner violence (IPV) against women, HIV incidence, and certain sexual risk behaviors of adding the Safe Homes and Respect for Everyone (SHARE) Project into ongoing HIV treatment and prevention activities of the Rakai Health Sciences Programme (RHSP). | Cluster randomized design, cohort study (n=5,337 intervention, n=6,111 control) that took place in Uganda over 4 years and 7 months. | • Raising awareness: stimulating dialogue • Building networks: preparing community for changes in perception & behavior • Integrating action: scale up to involve institutional policies • Consolidating efforts: preparing communities to take full ownership of intervention for sustainability |

• Intervention could reduce some forms of intimate partner violence (IPV) towards women and overall HIV incidence. • Physical IPV, sexual IPV, and rape lower in intervention group at second follow-up. • Male reports of perpetrating IPV not significantly affected by intervention. • Differences in emotional IPV were not significant. |

| Wekesah et al. (2016) | Systematic review of non-drug interventions improving maternal healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. | Systematic review included 73 studies on the effectiveness of interventions to improve quality and outcomes of maternal healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa published between 2000–2015. | • Systematic review of non-drug interventions improving maternal healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. | • Non-drug interventions directly or indirectly improved quality of maternal health and morbidity/mortality outcomes. • CM increased community awareness regarding seeking and using skilled maternity care. • Use of incentives, vouchers, fee exemptions, and community based health insurance schemes increased use of maternal health care by underserved populations. • Capacity building at the facility level increased quality of care • Task shifting is viable alternative to care at the facility, but requires appropriate training and ongoing supervision. |

| Zamawe et al. (2016) | Investigate whether participation in women’s groups was associated with contraceptive use in Malawi. | Community based, cross-sectional study (n=3,435 women that took place in Malawi over five years. | • Community Action Cycle | • Women’s groups improved uptake of contraceptives by 26%. • Uptake was almost the same among non-members of women’s groups. • Uptake of contraceptives wasn’t significantly different between groups. |

Abbreviations: ANC = antenatal care; CHW = community health worker; CM = community mobilization; FP = family planning; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IPV = intimate partner violence; MWH = maternity waiting home

Interventions for maternal and child health in SSA using CM included a variety of health concerns and outcomes in this review. Some focused on changing social norms that influence maternal morbidity and mortality such as female genital cutting (FGC; Babalola et al., 2006), the provision of safe post abortion care (Undie et al., 2014), or use of community distributed misoprostol to decrease post-partum hemorrhage (Ejembi et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2012). A focus on CM for education regarding a number of topics that influence maternal and child morbidity and mortality were also included such as modern family planning (Babalola et al., 2001; Gullo et al., 2017; Zamawe et al., 2016); prenatal, postnatal, and safe newborn practices (Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Mseu et al., 2014); maternal and child dietary practices (Guyon et al., 2009); and intimate partner violence (Wagman et al., 2015). One article focused on an evaluation of the cost effectiveness of CM alone or in combination with a facility quality improvement initiative (Colbourn et al., 2015). Several articles focused more directly on the reduction of maternal and child mortality through training of community health workers and traditional birth attendants (Boone et al., 2016), combining quality improvement at the facility level with community interventions led by women’s groups (Colbourn et al., 2013), or use of team training using local competencies and maternity waiting homes (Lori et al., 2013). One systematic review focused on non-drug interventions using CM in SSA (Wekesah et al., 2016) and another on the role of CM in SSA and the specific impact on HIV positive women (Colbourn et al., 2013). Three themes emerged from the literature including: 1) an increased knowledge or awareness of the health concern(s) being addressed, 2) impact on health outcomes, and 3) integral components to community mobilisation. See Table 3 for a summary of the results across studies.

Table 3.

Summary of Themes Organized by Study

| Authors & Year | Increased Knowledge/Awareness |

Impact on Health Outcomes |

Integral Components to CM Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Babalola et al. (2006) | • Increased perceived self efficacy to not perform FGC • Decreased personal approval of FGC • Increased perceived social support for ending FGC • Increased personal advocacy for eliminating FGC |

• Results used to inform policy abolishing FGC | • Implemented at hamlet, local government authority, and state level • Involved traditional leaders, local government officials, school groups, women’s groups, and pre-existing social forums • Use of mass media; regular newspaper columns, radio call in shows, public forums on FGC. |

| Babalola et al. (2001) | • CM showed a twofold increase in knowledge of FP methods. • CM increased dialogue about contraception, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV, child survival. • CM is an effective method of behavior change. |

• Increases in use of clinic based health services, modern FP. • Higher impact seen in one of the districts in comparison to the other. |

• Use of pre-existing Njangi groups/ meetings • Meetings with local stakeholders for project advocacy & sharing ownership |

| Boone et al. (2016) | • Caregivers in intervention group had improved knowledge and care seeking behavior. | • Intervention group had decreased maternal deaths • Under 5 mortality did not decrease. • House-holds in intervention group had decreased morbidity and higher under-standing of how to treat morbidities |

• Local leaders involved in process • Standard country protocols used in training community health workers and traditional birth attendants • Villages selected the traditional birth attendants to be involved in project |

| Colbourn et al. (2013) | • Women’s groups implemented a variety of strategies to address maternal & child health, likely raising awareness in the community (although not measured). | • Increase in facility delivery after policy change. • CM + quality improvement reduced neonatal mortality. • CM alone reduced perinatal mortality. • No impact on maternal mortality. |

• Village volunteers selected by research team and local chiefs. • CM with simultaneous facility quality improvement had the most impact. |

| Colbourn et al. (2015) | • Article assessed cost effectiveness only | • Community intervention more effective and less expensive than facility intervention. • Community intervention combined with facility intervention most cost effective. |

• Article assessed cost effectiveness only. |

| Ejembi et al. (2014) | • 99.7% of women reported acceptability of misoprostol (would recommend to a friend/family member) • Community dialogues identified two methods by which community members could identify 500 ml of blood loss (rubber cup/moda or 2 yards of commonly used cotton fabric soaked) |

• Project results informed health policy in Nigeria, then scaled up across the country. | • Community drug keepers identified by community members and leaders. • Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) can be trained/supervised and are a critical part of the team. • Intervention tailored to cultural norms of purdah, which results in high number of homebirths and need for emergency care in the community. |

| Ekirapa Kiracho et al. (2017) | • Primiparas, women of lower wealth quintiles, and with less formal education benefitted from having community healthworkers visit them at home to deliver health messages related to ANC and safe newborn practices. • Women with health worker visit more likely to attend ANC in first trimester. • Women with four ANC visits were 42% more likely to deliver at a facility. • Women who saved money for maternal health at least two times more likely to have facility delivery. |

• Increase in ANC visits • Increase in safer newborn practices |

• District and community level stakeholders identified the methods to be used and controlled implementation and adaptation of strategies as needed. |

| Gullo et al. (2017) | • Intervention builds capacity of community members and healthcare providers. • Increased satisfaction with reproductive health services. • 57% increase in use of modern contraceptives. |

• Intervention increased community health worker prenatal home visits by 20%, and postnatal home visits increased by 6%. • Modern contraceptive use increased by 57%. • Women’s satisfaction with reproductive health services increased. |

• Improved relationships between community health workers and the community. • Improved training/support for community health workers. |

| Guyon et al. (2009) | • CM intervention key in developing supporting policy environment & development of national guidelines. | • Increased and improved practices around breastfeeding. | • Multiple local partners used consistent, harmonized approach to ensure delivery of consistent messages. |

| Lori et al. (2013) | • Not assessed, however intervention inherently increased the awareness of what TBAs training/skills are to midwives and vice versa. | • Communities with a MWH had lower rates of maternal/ perinatal death. • Increase in team births in control and intervention sites. |

• Integration of care by traditional birth attendants and midwives. • Sharing and partnering with government: MWH included in Liberia’s accelerated action plan to reduce neonatal and maternal mortality. |

| Mburu et al. (2012) | • Networks of people living with HIV can increase awareness/reach those who are unable to be reached by the healthcare system. • Encourages male participation. |

• Not measured; though this approach is implied to decrease vertical transmission of HIV. | • Networks of peer support were effective. • Inclusion of income generating activities may strengthen sustainability. |

| Mseu et al. (2014) | • Increased awareness of need for ANC and breastfeeding, but lack of retention. | • Increase in ANC visits, education level correlated with total number of ANC visits | • Despite increased awareness, cultural myths impacted uptake/action. • Local context explored through qualitative data collection. |

| Muzyamba et al. (2017) | • Causal links exist for empirical evidence linking CM to better health outcomes for HIV negative women. This is lacking for HIV positive women. | • Reductions in maternal depression, reduced rates of hemorrhage, reduced neonatal and maternal mortality reported in CM studies. | • Biomedical model undermines local competencies. |

| Prata et al. (2012) | • CM delivered messages reached 80–90% of women, with a high retention of knowledge post intervention. | • Direct health outcomes not measured. • 83% of women interviewed postpartum identified that hemorrhage could be fatal. • 97–99% of postpartum women interviewed knew about the use of misoprostol to prevent deaths from hemorrhage. |

• CM showed that TBA or person helping with the birth could provide education about safe use of misoprostol. • Women identified TBAs as the most important source of information regarding misoprostol 41% of the time. • Community members identified culturally appropriate ways to measure blood loss and spread intervention information. |

| Rosato et al. (2012) | • Not assessed directly, although CM enacted through women’s groups is designed to increase awareness/knowledge and build capacity around solving health problems. | • Not assessed in this manuscript, although CM intervention was directed at decreasing maternal & neonatal mortality. | • Women’s groups designed and implemented on average 8 different strategies. |

| Undie et al. (2014) | • Raised awareness of FP methods. • Raised awareness about early pregnancy bleeding. |

• Increased proportion of women who reported early pregnancy bleeding. | • Supported by Kenya’s Ministry of Health and its Community Management Strategy • Supported by Naivasha District Health Management Team • Trained healthcare providers at existing clinics and dispensaries |

| Wagman et al. (2015) | • This was not directly measured, although the intervention was directed at changing attitudes, behaviors, and social norms related to IPV. | • Physical and sexual intimate partner violence as well as rape decreased in intervention group at second follow up. • Differences in emotional intimate partner violence were not significant. • Male reports of perpetrating intimate partner violence were not significantly affected by the intervention. |

• Implemented intervention within a pre-existing community clusters for a previous family planning trial. |

| Wekesah et al. (2016) | • 3 studies indicated that CM increased the level of health information related to danger signs and risk factors in pregnancy, first ANC visits, health facility use, and deliveries. | • Non-drug interventions directly or indirectly improved quality of maternal health and morbidity/ mortality outcomes. | • Comprehensive interventions that work to strengthen across sectors of existing healthcare systems (at the community and health facility level) along with supportive policy environments can improve care and reduce mortality. |

| Zamawe et al. (2016) | • CM intervention raised awareness related to maternal & neonatal health and safe delivery, although this was not directly measured. | • Women’s groups improved uptake of contraceptives by 26% for both women who were in the groups as well as non-members in the community. | • Intervention supported by pre-existing MaiMwana project and Malawi Ministry of Health |

Abbreviations: ANC = antenatal care; CHW = community health worker; CM = community mobilization; FP = family planning; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IPV = intimate partner violence; MWH = maternity waiting home

Increased Knowledge or Awareness

Multiple studies included in the review found that CM improved knowledge and/or awareness of maternal and/or child health concern(s) being addressed through their interventions (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Boone et al., 2016; Ejembi et al., 2014; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Gullo et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Lori et al., 2013; Mburu et al., 2012; Prata et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015; Zamawe & Mandiwa, 2016). Gullo et al. (2017) incorporated facilities, community healthworkers, and community members into the CAC, finding that community members gained awareness of the challenges that local health service delivery are faced with and often unable to control.

One study evaluated the knowledge and practices of childbearing age women in Malawi following a Safe Motherhood project that provided education regarding timing of visits for antenatal care, services provided at antenatal care visits, recommended number of antenatal visits, advice regarding facility delivery, information about safe newborn practices, postnatal care, immunizations, malaria prevention, and male involvement in childcare (Mseu et al., 2014). While results showed increases in knowledge and awareness, the authors suggested that cultural considerations are an important element to consider. For example, qualitative data from this study revealed that despite 100% reported knowledge of malaria prevention through bednets, in reality cultural myths continued to hinder use (Mseu et al., 2014). Another study focused on the reduction of death from post-partum hemorrhage placed early emphasis on gaining cultural insight throughout the study design, tailoring messages to account for cultural norms wherein community members helped identify a common household item that could be consistently used to measure 500 ml of blood loss, and encouraged a simple message to be printed on hijabs, headscarves for Christian women, and water kettles for ablutions for Muslim men (Prata et al., 2012). At endline, results indicated ~50% knowledge retention with only 51% of women expressing willingness to take the CM proposed action in the event of post-partum hemorrhage, echoing the significance of cultural influence and introducing the importance of retention assessment (Prata et al., 2012).

Babalola et al., (2006) reported an increased impact when CM was combined with mass media strategies compared to CM alone. This study took place in Nigeria, evaluating the impact of CM verses CM in addition to mass media strategies regarding FGC. Mass media strategies included state level campaigns sponsored by the National Association of Women Journalists that included, “regular newspaper columns, radio call in shows, and public forums,” (Babalola et al., 2006, p. 1595). They found that CM efforts alone decreased intention to perform FGC by 40% among women and 37.6% among men (Babalola et al., 2006). Community mobilisation in addition to mass media strategies increased the intention of men and women not to perform FGC by an additional 17.1% and 22.9% respectively, reflecting the added power of including mass media strategies with CM efforts (Babalola et al., 2006)

Impacting Health Outcomes

A second common theme across multiple studies was the impact of CM on health outcomes. Multiple articles reported reductions in maternal and/or child mortality rates following CM interventions (Boone et al., 2016; Colbourn, et al., 2013; Lori et al., 2013). Colbourn et al. (2013) combined CM in the community with a quality improvement initiative at the facility level, finding the combined approach decreased late neonatal mortality by 22%, while the CM approach alone decreased perinatal mortality by 16%. Neither approach influenced maternal mortality suggesting that different approaches may influence different outcomes. Numerous articles also reported changes in relation to the specific health related behavior targeted by their CM interventions. These included an increase in uptake of modern contraceptive methods (Gullo et al., 2017; Zamawe & Mandiwa, 2016), increases in facility deliveries (Colbourn et al., 2013; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017), an increase in team births (Lori et al., 2013), increased dialogue about culturally sensitive topics (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Ejembi et al., 2014; Gullo et al., 2017; Mburu et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015; Zamawe et al., 2016), increased intention of care seeking behaviors (Boone et al., 2016; Undie et al., 2014), increases in the number of antenatal care visits (Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Mseu et al., 2014), increases in safe newborn practices (Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017), improvement in breastfeeding practices (Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009), improved child and maternal dietary and feeding practices (Guyon et al., 2009) increased reliance on peer support and community networks for health concerns (Mburu et al., 2012; Prata et al., 2012; Rosato et al., 2012), a decrease in intimate partner violence (Wagman et al., 2015), and decreased intention to perform FGC (Babalola et al., 2006). One systematic review concluded CM interventions in SSA have been focused on the health of HIV negative women and lack studies on CM for HIV positive women (Muzyamba et al., 2017).

Multiple articles included in the review also focused on system issues such as cost, personnel included in the delivery of care, and satisfaction. For instance, several articles found CM to be a cost effective method for improving health outcomes, having the potential to change the way care is delivered or funding is distributed in this region (Colbourn et al., 2013; Guyon et al., 2009). Four articles emphasized utilization of local competency in their CM intervention by incorporating training and inclusion of traditional birth attendants into their design (Boone et al., 2016; Ejembi et al., 2014; Lori et al., 2013; Prata et al., 2012). A cluster randomized design that facilitated community and health system dialogues through the community action cycle method found an increase in service utilization, improvement in training and support for community health workers, and increased satisfaction with health services (Gullo et al., 2017). Notably, multiple CM interventions included in the review were translated into action plans or policies at the local or national levels to broaden the expansion of their success (Babalola et al., 2006; Ejembi et al., 2014; Lori et al., 2013; Prata et al., 2012). One systematic review examining non-drug interventions for maternal and child health in SSA echoed the importance of expanding these strategies, concluding that supportive policy environments are essential in improving maternal and child healthcare and reducing mortality in this region (Wekesah et al., 2016).

Components Integral to CM

Finally, it was noted that CM is reliant on components related to the incorporation of existing structures, partnership building, and local context. Existing structures were reflected through use of local community groups or leaders to drive or support the CM strategy (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Colbourn et al., 2013; Colbourn et al., 2015; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Mburu et al., 2012), community health workers (Boone et al., 2016; Colbourn et al., 2015; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Gullo et al., 2017; Undie et al., 2014), or traditional birth attendants (Ejembi et al., 2014; Boone et al., 2016; Lori et al., 2013; Prata et al., 2012; Rosato et al., 2012 ) in the majority of articles. Partnership building on local, regional, and/or national levels were emphasized as necessary in creating meaningful, sustainable, or scalable CM interventions (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Boone et al., 2016; 2014; Colbourn, et al., 2013; Colbourn, et al., 2015; Ejembi et al., 2014;Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Gullo et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Lori et al., 2013; Mburu et al., 2012; Mseu et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2014; Rosato et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015; Wekesah et al., 2016). Partnerships included those between local government officials, Ministry of Health, or local non-governmental organizations (Ejembi et al., 2014; Gullo et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Mburu et al., 2012; Mseu et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2012; Rosata et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015) and/or local tribal leaders, chiefs, or cultural leaders (Ejembi et al., 2014; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Gullo et al., 2017; Prata et al., 2012; Rosata et al., 2012). Local context drove the design of CM through strategies tailored by socio-cultural preferences or beliefs, political influence, and/or environmental, geographical, or historical factors (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Boone et al., 2016; Colbourn, et al., 2013; Colbourn, et al., 2015; Ejembi et al., 2014;Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Gullo et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Lori et al., 2013; Mburu et al., 2012; Mseu et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2014; Rosato et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015; Wekesah et al., 2016; Zamawe et al., 2016).

Discussion

Three main themes were identified from this scoping review: awareness or knowledge, impacting health outcomes, and components integral to CM. It was noted that the majority of CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA impacted the community member’s awareness or knowledge of the health concern in question. A few articles incorporated considerations of knowledge or awareness retention and the power of cultural beliefs as they influence the transition beyond knowledge to action. Overall, the articles in the review support CM as a strategy to improve a variety of health outcomes that impact maternal and child health in SSA, and explored a variety of ways in which this might occur at the community level and in some cases, in conjunction with system level transformations. Finally, there were three components that were illustrated as integral to the process of CM in this region; use of existing structures, partnership building, and local context.

Gaps in Defining CM and Empowerment

Despite the evidence elicited in this review supporting CM interventions for maternal and/or child health interventions in SSA, there was a lack of exploration or measurement of how empowerment functions in CM interventions. Similarly, there was inconsistency among the articles in how CM was defined. The majority of studies included in the review were lacking in a definition entirely which impacts the clarity of CM as a strategy (Babalola et al., 2006; Babalola et al., 2001; Boone et al., 2016; Ejembi et al., 2014; Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017; Colbourn et al., 2015; Gullo et al., 2017; Guyon et al., 2009; Lori et al., 2013; Mburu et al., 2012; Mseu et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2012; Rosato et al., 2012; Undie et al., 2014; Wagman et al., 2015; Wekesah et al., 2016; Zamawe & Mandiwa, 2016). One systematic review provided a list of definitions and extracted what they identified as three main principles utilized to varying degrees by implementers of CM, which they identified as, “reliance on peer support, use of indigenous resources in care provision, and/or collaboration between community and professionals in designing maternal care initiatives,” (Muzyamba et al., 2017, p. 4). Some of the studies lacking in a definition were explicit in stating that their methodology was the Community Action Cyle or a variation therein, which illustrated a clearer picture of the assumed definition (Babalola et al., 2001; Babalola et al., 2006; Colbourn et al., 2013; Colbourn et al., 2015; Gullo et al., 2017; Lori et al., 2013; Undie et al., 2014; Prata et al., 2012; Rosato et al., 2012; Zamawe & Mandiwa, 2016). Another study that did not provide a definition of CM stated use of Susman’s Participatory Action research method, which appears similar in description to the Community Action Cycle, as it includes a five phase cycle of problem identification, action, evaluation, and lessons learned (Ekirapa-Kiracho et al., 2017). Wekesah et al. (2016) did not specifically define CM in their systematic review, although they did describe the elements included in the process and emphasized the goal of attaining a shift in power dynamics through empowerment. Notably, none of the studies defined or measured empowerment in their articles, though several suggested empowerment as an outcome or suggested a need for empowerment in their conclusions (Colbourn et al., 2013; Colbourn et al., 2015; Mburu et al., 2012; Mseu et al., 2014; Wekesah et al., 2016). Despite a search strategy framed to capture how CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA impact the empowerment of individuals involved, no conclusions can be drawn regarding this question due to the absence of data found in this literature. This also represents a gap in the knowledge base around the impact of empowerment on individuals involved in and at the periphery of CM interventions for maternal and child health in SSA.

Limitations

This scoping review is not without its limitations. The articles included were only in English, which may have excluded CM interventions taking place in countries in SSA where other languages are the official languages for business, education, and writing. The small ratio of countries represented in this review may be an artifact of linguistics as mentioned, or a lack of data on this topic. As the search was limited to peer reviewed literature, it is possible that some CM interventions published in the grey literature were missed. Furthermore, the absence of any studies measuring the impact of empowerment on individuals following CM interventions may be due to a true paucity of data or the fact that social science or economics databases were not included in the review. In addition, the variability in definitions of CM could have impacted the results and reporting of interventions, limiting the scope of this review. Similarly, some interventions designed as CM may not be included due to a failure to specifically report the results using CM terminology.

Conclusion

Improvements in maternal and child health in SSA and work towards achieving SDG 3 require solutions that address the multitude of factors influencing outcomes. Community mobilisation is an effective strategy to holistically improve maternal and child health in SSA, but as revealed by this scoping review, is rarely defined in the research outside of operational terms as part of the Community Action Cycle, or adaptations of this approach. Researchers should define CM as they are using it in their interventions to improve clarity and the foundation for scaling up, and a stronger evidence base lending itself to systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Although limiting this strategy to one definition may not be possible due to the necessity on the part of researchers to design interventions with local relevance as a key priority, perhaps the approach suggested by Muzyumba et al. (2017) in listing key principles would be feasible. Alternatively, the use of a broad, all encompassing definition such as the one put forth by Howard-Grabman et al. (2007) and provided earlier in this review may also provide enough discretion for researchers to operationalise and tailor it to their unique context.

As CM is anchored in the process of empowerment, studies investigating CM would benefit by defining and measuring empowerment. Empowerment can be assessed as a process or an outcome and is measured by different fields in discipline specific manners. It has been put forth that empowerment specific to women at micro levels involves self efficacy, beyond that it incorporates a major emphasis on agency, and beyond that, social inclusion (Malhotra, Schuler & Boender, 2002). Agency is emphasized as a crucial piece of the empowerment of women as it has been illustrated that providing resources with no accompanying facilitation of women’s recognition and ability to use them does not equate with empowerment (Malhotra, Schuler & Boender, 2002). Schuler et al. (1991) emphasize the importance of qualitative research and or micro-ethnographies to understand women’s empowerment contextually and relevant indicators to update these conceptualizations as needed. Defining and measuring empowerment in CM interventions through qualitative or micro-ethnographic work would be valuable in the creation of context specific validated measures. Community mobilisation is an important research process for engaging the community to ensure that interventions are meeting the needs of the community, take into account the local context, and are sustainable. While CM has demonstrated improvement in health outcomes and systems throughout SSA, additional work around definitions and measurement is needed to advance the science.

Table 4.

Effect of Community Mobilization

| Authors & Year | Effect of Community Mobilization |

|---|---|

| Babalola et al. (2006) | CM effective at decreasing FGC |

| Babalola et al. (2001) | CM is an effective method of increasing use of clinic services & FP impact higher in one district than the other |

| Boone et al. (2016) | CM effective in decreasing maternal deaths, but not under 5 mortality |

| Colbourn et al. (2013) | CM and quality improvement decreased neonatal mortality, CM alone decreased perinatal mortality, no impact on maternal mortality |

| Colbourn et al. (2015) | Article assessed cost effectiveness only, indicated CM as a cost effective strategy |

| Ejembi et al. (2014) | CM effective in supporting a sustainable, culturally acceptable, distribution of misoprostol at community level. |

| Ekirapa Kiracho et al. (2017) | CM effective in increasing in ANC visits & safer newborn practices |

| Gullo et al. (2017) | CM effective in building capacity of community members and healthcare providers, as well as influencing health practices and satisfaction |

| Guyon et al. (2009) | CM intervention key in increasing and improving breastfeeding practices |

| Lori et al. (2013) | Not assessed directly, although CM intervention increased team births and health facilities with MWHs had lower rates of maternal & perinatal death |

| Mburu et al. (2012) | CM increased awareness of those unable to be reached by the healthcare system and encouraged male participation |

| Mseu et al. (2014) | CM increased awareness of need for ANC and breastfeeding. |

| Muzyamba et al. (2017) | Causal links exist for empirical evidence linking CM to better health outcomes for HIV negative women; this is lacking for HIV positive women |

| Prata et al. (2012) | CM messages about PPH & misoprostol reached 80–90% of women, with a high retention of knowledge |

| Rosato et al. (2012) | Not assessed directly, although CM women’s groups increase awareness/knowledge and build capacity |

| Undie et al. (2014) | CM raised awareness of FP methods and early pregnancy bleeding. |

| Wagman et al. (2015) | CM intervention resulted in decreased intimate partner violence at second follow-up (35 months) |

| Wekesah et al. (2016) | 3 studies indicated that CM increased the level of health information related to danger signs and risk factors in pregnancy, first ANC visits, health facility use, and deliveries |

| Zamawe et al. (2016) | Not assessed directly; although the CM intervention raised awareness related to maternal & neonatal health & safe delivery |

Abbreviations: ANC = antenatal care; CM = community mobilization; FGC = female genital cutting; FP = family planning; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus; TBA = traditional birth attendant; MWH = maternity waiting home

References

- Altman L, Sebert Kuhlmann A.K., Galavotti C (2015). Understanding the black box: A systematic review of the community mobilization process in evaluations of interventions targeting sexual, reproductive, and maternal health. Evaluation Program Planning, 49, 86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Babalola S, Brasington A, Agbasimalo A, Helland A, Nwanguma E, & Onah N (2006). Impact of a communication programme on female genital cutting in eastern Nigeria. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 11(10), 1594–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalola S, Sakolsky N, Vondrasek C, Mounlom D, Brown J, & Tchupo JP (2001). The impact of a community mobilization project on health-related knowledge and practices in Cameroon. Journal of Community Health, 26(6), 459–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone P, Elbourne D, Fazzio I, Fernandes S, Frost C, Jayanty C, et al. (2016). Effects of community health interventions on under-5 mortality in rural Guinea-Bissau (EPICS): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet.Global Health, 4(5), e328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn T, Nambiar B, Bondo A, Makwenda C, Tsetekani E, Makonda-Ridley A, et al. (2013). Effects of quality improvement in health facilities and community mobilization through women’s groups on maternal, neonatal and perinatal mortality in three districts of Malawi: MaiKhanda, a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness trial. International Health, 5(3), 180–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn T, Pulkki-Brännström A −., Nambiar B, Kim S, Bondo A, Banda L, et al. (2015). Cost-effectiveness and affordability of community mobilisation through women’s groups and quality improvement in health facilities (MaiKhanda trial) in Malawi. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 13(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejembi C, Shittu O, Moran M, Adiri F, Oguntunde O, Saadatu B, et al. (2014). Community-level distribution of misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage at home births in northern Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 18(2), 166–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Kananura RM, Tetui M, Namazzi G, Mutebi A, George A, et al. (2017). Effect of a participatory multisectoral maternal and newborn intervention on maternal health service utilization and newborn care practices: A quasi-experimental study in three rural Ugandan districts. Global Health Action, 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo S, Galavotti C, Sebert Kuhlmann A., Msiska T, Hastings P, & Marti CN (2017). Effects of a social accountability approach, CARE’s community scorecard, on reproductive health-related outcomes in Malawi: A cluster-randomized controlled evaluation. PloS One, 12(2), e0171316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon AB, Quinn VJ, Hainsworth M, Ravonimanantsoa P, Ravelojoana V, Rambeloson Z, et al. (2009). Implementing an integrated nutrition package at large scale in Madagascar: The essential nutrition actions framework. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 30(3), 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Grabman L, Storti C, Hummer P, Pooler B; Geneva: USAID, (2007).Demystifying Community Mobilization: an effective strategy to improvematernal and newborn health. Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadi338.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lechner M (2011) The estimation of causal effects by difference in difference methods,foundations and trends. Econometrics, 4(3) 165–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lori JR, Munro ML, Rominski S, Williams G, Dahn BT, Boyd CJ, et al. (2013). Maternity waiting homes and traditional midwives in rural Liberia. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 123(2), 114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Schuler S, Boender C, (2002). Measuring Women’s Empowerment as a variable in International Development. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEMPOWERMENT/Resources/486312-1095970750368/529763-1095970803335/malhotra.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mburu G, Iorpenda K, & Muwanga F (2012). Expanding the role of community mobilization to accelerate progress towards ending vertical transmission of HIV in Uganda: The networks model. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 15 Suppl 2, 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mseu D, Mkwinda Nyasulu B, & Rose Muheriwa S (2014). Evaluation of a safe motherhood project in Ntcheu district, Malawi . International Journal of Women’s Health, 6, 1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyamba C, Groot W, Tomini SM, & Pavlova M (2017). The role of community mobilization in maternal care provision for women in sub-Saharan Africa- A systematic review of studies using an experimental design. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prata N, Ejembi C, Fraser A, Shittu O, & Minkler M (2012). Community mobilization to reduce postpartum hemorrhage in home births in northern Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(8), 1288–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosato M, Malamba F, Kunyenge B, Phiri T, Mwansambo C, Kazembe P, et al. (2012). Strategies developed and implemented by women’s groups to improve mother and infant health and reduce mortality in rural Malawi. International Health, 4(3), 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Islam F, Rottach E, (2010) Women’s empowerment revisited: a case study from Bangladesh. Dev Pract. 2010 September 1; 20(7): 840–854. Doi: 10.1080/09614524.2010.508108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Care Institute for Excellence, (2003) Types and Quality of Knowledge in Social Care, Social Care Institute for Excellence, London. Retrieved from www.scie.org.uk/publications/knowledgereviews/kr03-summary.pdf

- The Library of Congress (2010). Africana Collections: List of sub-Saharan countries. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/rr/amed/guide/afr-countrylist.html

- Undie CC, Van Lith LM, Wahome M, Obare F, Oloo E, & Curtis C (2014). Community mobilization and service strengthening to increase awareness and use of postabortion care and family planning in Kenya. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 126(1), 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2017) Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

- Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, Thoma M, Ndyanabo A, Ssekasanvu J, et al. (2015). Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: Analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. The Lancet Global Health, 3(1), e23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekesah FM, Mbada CE, Muula AS, Kabiru CW, Muthuri SK, & Izugbara CO (2016). Effective non-drug interventions for improving outcomes and quality of maternal health care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Helath Organization, (2017). Children: Reducing Mortality Fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs178/en/

- World Health Organization (2016). Maternal Mortality Factsheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/

- World Health Organization (2015) Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990–2015. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/12/Trends-in-MMR-19902015_Full-report_243.pdf

- Zamawe COF, & Mandiwa C (2016). Understanding the mechanisms through which women’s group community participatory intervention improved maternal health outcomes in rural Malawi: Was the use of contraceptives the pathway? Global Health Action, 9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]