Abstract

Two histopathological subtypes of Meniere's disease (MD) were recently described in a human post-mortem pathology study. The first subtype demonstrated a degenerating distal endolymphatic sac (ES) in the affected inner ear (subtype MD-dg); the second subtype (MD-hp) demonstrated an ES that was developmentally hypoplastic. The two subtypes were associated with different clinical disease features (phenotypes), suggesting that distinct endotype-phenotype patterns exist among MD patients. Therefore, clinical endotyping based on ES pathology may reveal clinically meaningful MD patient subgroups. Here, we retrospectively determined the ES pathologies of clinical MD patients (n = 72) who underwent intravenous delayed gadolinium-enhanced inner ear magnetic resonance imaging using previously established indirect radiographic markers for both ES pathologies. Phenotypic subgroup differences were evidenced; for example, the MD-dg group presented a higher average of vertigo attacks (ratio of vertigo patterns daily/weekly/other vs. monthly, MD-dg: 6.87: 1; MD-hp: 1.43: 1; p = 0.048) and more severely reduced vestibular function upon caloric testing (average caloric asymmetry ratio, MD-dg: 30.2% ± 30.4%; MD-hp: 13.5% ± 15.2%; p = 0.009), while the MD-hp group presented a predominantly male sex ratio (MD-hp: 0.06:1 [f/m]; MD-dg: 1.2:1 [f/m]; p = 0.0004), higher frequencies of bilateral clinical affection (MD-hp: 29.4%; MD-dg: 5.5%; p = 0.015), a positive family history for hearing loss/vertigo/MD (MD-hp: 41.2%; MD-dg: 15.7%; p = 0.028), and radiographic signs of concomitant temporal bone abnormalities, i.e., semicircular canal dehiscence (MD-hp: 29.4%; MD-dg: 3.6%; p = 0.007). In conclusion, this new endotyping approach may potentially improve the diagnosis, prognosis and clinical decision-making for individual MD patients.

Keywords: endolymphatic sac, patient subgroups, phenotype, degeneration, hypoplasia

Introduction

A major challenge in diagnosing and managing patients with Meniere's disease (MD) is its heterogeneous clinical presentation (i.e., phenotypic differences among patients) (1). For example, vestibular and auditory symptoms may occur together or in a temporally independent manner, in varying frequency patterns (e.g., daily, monthly, episodically), and with some symptoms predominating over others (e.g., more pronounced vestibular than auditory symptoms) (2, 3). Symptom attacks may occur in response to identifiable triggers [e.g., high sodium intake, caffeine, stress, reviewed in (1, 4)] or in random patterns. In many cases, the disease remains unilateral (one inner ear clinically affected), whereas progression to bilateral disease is observed in ~40% of cases (2, 5). In the long-term, the degree of permanent hearing loss and vestibular hypofunction can remain mild to moderate or progress to severe levels (2). Identifying distinct phenotypic patterns among MD patients would potentially enable clinicians to predict clinical features or the disease course in individual MD patients.

In a recent post-mortem histopathology study on inner ear tissues from MD patients (6), we identified two histopathological subtypes of the disease: (i) epithelial degeneration of the endolymphatic sac (ES) and (ii) organ hypoplasia of the ES. Both ES pathologies result in loss of the normal ES epithelium and its ion transport functions. Loss of ES function presumably underlies the endolymphatic hydrops generation in MD and is believed to be a necessary precondition for MD's clinical symptomatology. We therefore consider the two ES pathologies to be etiopathologically distinct MD “endotypes” that may be associated with different phenotypical features. To investigate endotype-phenotype patterns in clinical patients, we previously developed a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT)-based imaging method to distinguish the two ES pathologies (7).

The present study aimed to (i) adapt the method to distinguish ES pathologies based on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (Gd-MRI); (ii) retrospectively subgroup a series of MD patients based on their ES pathology; and (iii) investigate, based on clinical data, whether these endotypes separate into clinically meaningful patient subgroups.

Methods

Study Design and Approval

This retrospective explorative study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (application KEK-ZH-Nr. 2016-01619, Kantonale Ethikkommission, Zurich, Switzerland) in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and its amendments. Written informed general consent was obtained from all participants.

Study Population

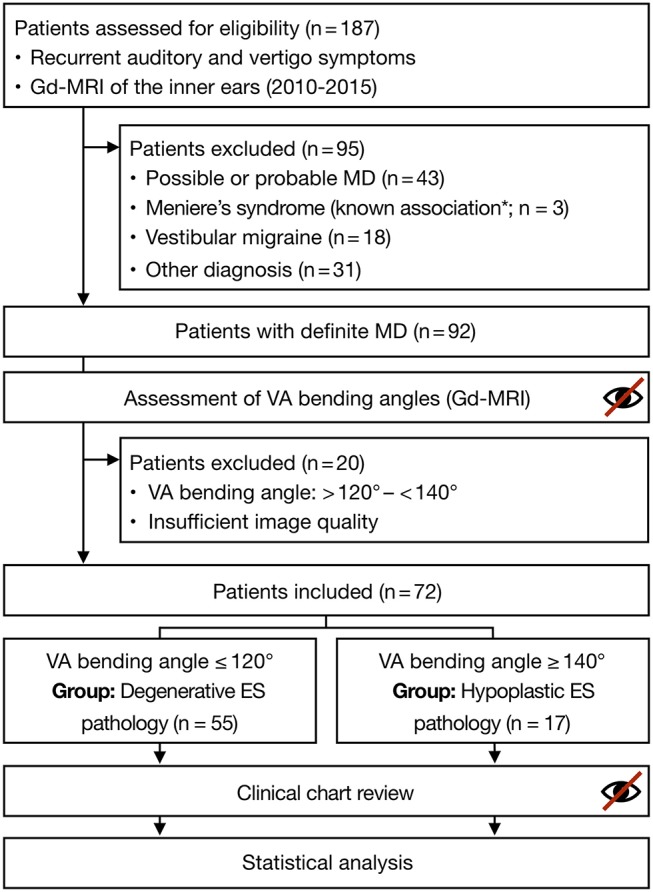

We retrospectively assessed consecutive patients who attended our interdisciplinary center for vertigo and balance disorders at the University Hospital Zurich (tertiary referral center) from January 2010 to December 2015 for eligibility to be included in the study. The inclusion criteria were available data from Gd-MRI of the inner ears [(8); n = 187] and a final diagnosis of uni or bilateral definite MD [(9); n = 92]. We excluded patients with a Meniere's-like symptom complex due to a secondary pathology [e.g., otosclerosis, vestibular schwannoma, history of temporal bone fracture, and Cogan's syndrome, reviewed in (10)], patients who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for possible or probable MD (9), and patients who were ultimately assigned another vertigo-associated diagnosis (e.g., vestibular migraine). Of the 92 primarily included MD patients, 20 were excluded after Gd-MRI data analysis (see “Vestibular aqueducts (VA) measurements and patient endotyping”). Finally, 72 patients' data were statistically analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. MD was definitively diagnosed per the guidelines from the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery for the Definition of Meniere's Disease from 1995 (9). VA bending angles and clinical chart reviews were assessed in a blinded manner (see text for details). *according to Merchant and Nadol (10). (Gd-MRI, gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; ES, endolymphatic sac; MD, Meniere's disease; VA, vestibular aqueduct).

Temporal Bone Imaging

During the routine clinical work-up, patients underwent 3-T MR imaging of the temporal bones 4 h after intravenous contrast (Gd) was administered to detect endolymphatic hydrops based on previously established protocols (8, 11). The endolymphatic hydrops grade (8) and signs of semicircular canal (SCC) dehiscence (i.e., absence of low-signal bone margins around the SCCs) were evaluated by experienced neuroradiologists at the time the images were taken. Additional dedicated temporal bone HRCT imaging was available for a subset of patients (n = 16). HRCT data were reconstructed separately for each temporal bone in the axial plane using a standard bone algorithm.

Vestibular Aqueduct (VA) Measurements and Patient Endotyping

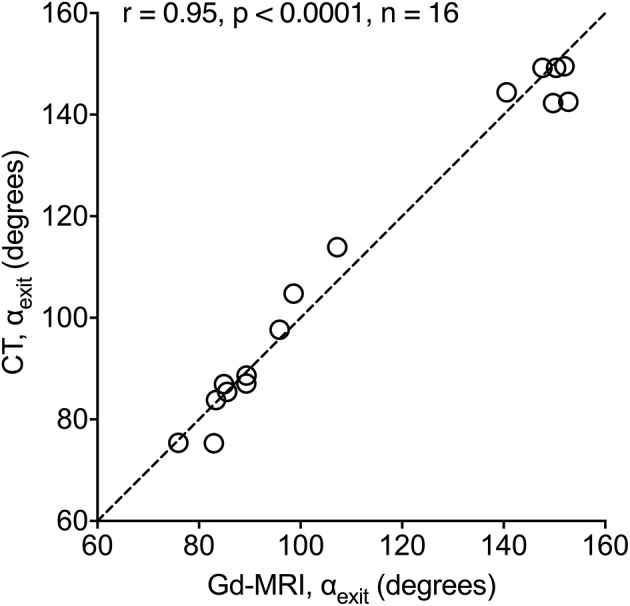

We recently established a method to clinically distinguish the two histopathological subtypes (ES degeneration vs. ES hypoplasia) using the vestibular aqueduct angular trajectory (ATVA) as a radiographic surrogate marker (7). We demonstrated that the two ES pathologies are associated with significantly different VA bending angles (αexit), which can be reliably determined using temporal bone HRCT imaging data and custom-developed software (12). Here, we validated the method for use with the Gd-MRI data by performing αexit measurements based on HRCT and Gd-MRI (T2 space or 3D inversion recovery sequence) data from the same MD patients (n = 16). The imaging datasets were presented to an investigator (DB) who performed all measurements in a randomized order. The measured angles revealed a strong intermodal correlation between the HRCT and Gd-MRI (Spearman correlation coefficient r = 0.95, p < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CT vs. Gd-MRI correlation for αexit. Angles were measured from HRCT and Gd-MRI data from the same 16 MD patients.

Previously determined reference values for αexit were used to endotype the MD patients (7). In clinically affected inner ears, angles ≤120° indicated a degenerative ES pathology. This subgroup is hereafter referred to as “MD-dg” patients. Angles ≥140° indicated a hypoplastic ES pathology, hereafter referred to as “MD-hp” patients. Of the 92 patients whose Gd-MRI-based ATVA was measured, 20 were excluded from the final analysis because of inconclusive αexit values (>120° and <140°) likely due to insufficient image quality from the Gd-MRI data.

Reproducibility of the ATVA Measurements

Internal consistency of the Gd-MRI-based angle measurements and patient endotyping was tested by two independent investigators (AE and DB) who reassessed the Gd-MRI data from a randomly selected 14% of the cases. The investigators were blinded to the previous measurements when remeasuring αexit and assigning cases to the endotype subgroups per the procedures described above. The interobserver test-retest reliability of the endotype assignments (MD-dg vs. MD-hp) was determined using Cohen's kappa coefficient (x). A x-value of 0.78 was determined, indicating excellent test-retest agreement per (13).

Clinical Data Collection and Processing

Clinical records, audiometric and vestibular test data, and radiology reports were reviewed by two investigators (CB and TH), who were blinded to the original imaging data and endotyping results. All data were collected in a structured digital database with predefined variables and categories. After collecting the data, all variables in the database were checked for categories with excessively low cell frequencies (<4). Those categories were merged with others from the same variable based on clinical meaningfulness to retain sufficient statistical power.

Statistical Analysis

Null hypotheses were formulated and statistical tests were selected before collecting the data. Second-step statistical analysis (post hoc testing) was clearly indicated (see respective paragraph). For binary variables, a chi-square test was performed if all category frequencies were greater than five; otherwise, Fisher's exact test was performed. Continuous variables were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t-test for independent samples if the data were normally distributed; otherwise, a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test was performed. If not otherwise specified, statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P-values were categorized into levels of evidence against H0 (very strong evidence, p < 0.001; strong evidence, p = 0.001–0.01; evidence, p = 0.01–0.05; weak evidence, p = 0.05–0.1; and little or no evidence, p > 0.1) per (14).

Multiple Testing Correction

Twenty-eight independent null hypotheses were tested on the sample data. (A Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple comparisons was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR) (15) see also the following paragraph). Subsequent p-values are followed by a statement regarding their significance per the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (significant [sig.] or not significant [n. s.]) (16).

Rationale for Choosing the FDR's Critical Value

This study's purpose was to exploratively and exhaustively screen for clinical variables that differed between the two predefined patient subgroups and that would potentially contribute to the variable's clinical meaningfulness. Therefore, in our statistical analysis, we intended to minimize the risk of false negatives (type II error) while retaining an appropriate risk of false positives (type I error), which was controlled by the FDR (15). In contrast to large-scale multiple-testing studies (e.g., genomics studies with >103 null hypotheses) that typically apply an FDR of 0.05 to minimize the type I error probability, we chose an FDR of 0.15. This value is associated with a reduced type II error rate and is commonly used in explorative and proof-of-concept studies (17, 18) in which not overlooking any true-positive results is prioritized.

Post hoc Analysis

In all contingency tables where significant differences were detected (based on an FDR of 0.15) between the groups, we performed post hoc testing per (19), enabling rigorous control of type I error rates: all three possible pairwise comparisons were performed between one variable and the other two, followed by a Bonferroni correction (in which the p-value is divided by the number of tests).

Longitudinal Analysis

To investigate whether the two MD endotypes differed in hearing loss progression over time (i.e., the slope of pure-tone averages [PTAs] respective of time), we performed a longitudinal analysis on data from each patient's repeated audiometric measurements. In bilateral cases, each ear was considered a separate case. A linear mixed-effects model was used with a subject-specific random intercept and a random slope for time. This model enabled varying baseline measurements and time-varying trends among subjects, considering data imbalance and unequal time-spacing. PTA measurements constituted the response, while time and endotype were the explanatory variables. Moreover, an interaction term between pathology type and time was included in the model to allow a pathology-specific time trend. The longitudinal analysis was performed in the R programming language using the function, lmer(), from the analysis-specific package, lme4 (20, 21).

Volume Reconstructions

Inner ear volumes (Figure 3) were reconstructed from Gd-MRI data using 3D Slicer software [version 4.8.1 for Mac OS X (22)].

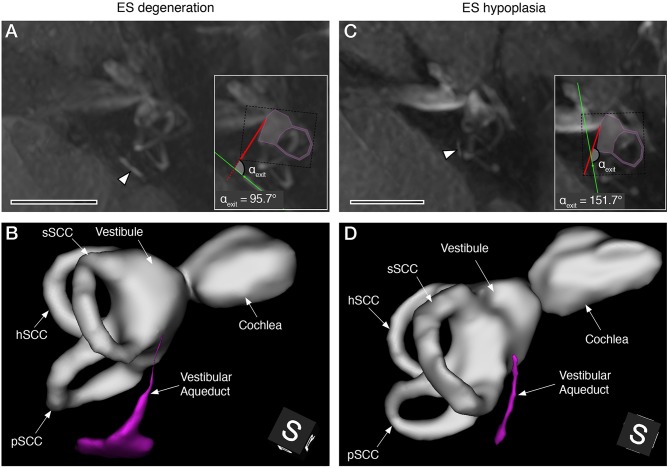

Figure 3.

Gd-MRI VA morphology in representative MD cases with degenerative (A,B) and hypoplastic (C,D) ES pathology. Maximum intensity projections of axial plane images (A,C), and 3D reconstructions (postero-superior view) of the labyrinthine fluid spaces with the VA shown in magenta (B,D). Arrowheads in (A,C) indicate the VA in the opercular region. Insets in (A,C) show angle measurements of the VA's angular trajectory as described previously (7) (sSCC, superior semicircular canal; hSCC, lateral semicircular canal; pSCC, posterior semicircular canal). Scale bars, 10 mm.

Results

Patient Endotyping and Baseline Characteristics

Of the 72 patients who were ultimately included, 55 (76.4%) demonstrated angles (αexit) ≤120° in the clinically affected inner ear(s). This subgroup was histopathologically diagnosed with ES degeneration (6) and is hereafter referred to as the MD-dg subgroup (Figures 3A,B). In 17 patients (23.6%), angles (αexit) ≥140° were observed, corresponding to a histopathological diagnosis of ES hypoplasia [(7); MD-hp subgroup; Figures 3C,D]. Table 1 shows the 72 endotyped patients' baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Key baseline characteristics of the study sample.

| Total MD patients included (n = 72) | |

|---|---|

| Female:male ratio | 41 (56.9%): 31 (43.1%) |

| Unilateral:bilateral ratio | 64 (88.9%): 8 (11.1%) |

| Disease duration (*) | 10.1 (6.1) years |

| Age at first MD symptoms | 46.8 (12.0) years |

| Age at inclusion | 56.8 (12.7) years |

Mean (SD) or absolute numbers (percentage).

Mean disease durations at inclusion were similar in both subgroups (MD-dg: 9.8 ± 6.4 years MD-hp: 10.6 ± 5.1 years; p = 0.685).

Between-Endotype Clinical Differences

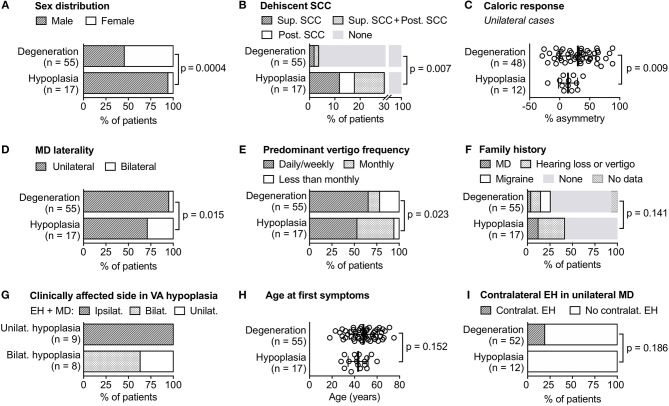

From 28 clinical variables (Table 2), seven variables showed evidence to very strong evidence (14) for group differences (MD-dg vs. MD-hp endotypes), which are highlighted together with other potentially clinically meaningful variables (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics tested for between-group differences.

| Variable | Degeneration (n = 55) | Hypoplasia (n = 17) | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | Benjamini-Hochberg significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female:male ratio | 30 (54.5%): 25 (45.5%) | 1 (5.9%): 16 (94.1%) | n. a. | 0.0004 | sig. |

| Headache type | |||||

| - Migraineous | 20 (36.4%) | 4 (23.5%) | |||

| - Non-migraineous | 5 (9.1%) | 8 (47.1%) | n. a. | 0.004 | sig. |

| - None | 30 (54.5%) | 5 (29.4%) | |||

| SCC dehiscence on affected side | 2 (3.6%) | 5 (29.4%) | n. a. | 0.007 | sig. |

| Caloric response asymmetry (unilateral cases)—% asymmetry | 30.2 ± 30.4 (n = 48) | 13.5 ± 15.2 (n = 12) | 16.7 (4.4 to 29.1) | 0.009 | sig. |

| Laterality | |||||

| - Unilateral | 52 (94.5%) | 12 (70.6%) | n. a. | 0.015 | sig. |

| - Bilateral | 3 (5.5%) | 5 (29.4%) | |||

| Vertigo frequency | |||||

| - Daily/weekly | 36 (65.5%) | 9 (52.9%) | |||

| - Monthly | 7 (12.7%) | 7 (41.2%) | n. a. | 0.023 | sig. |

| - Other | 12 (21.8%) | 1 (5.9%) | |||

| Family history | |||||

| - MD | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (11.8%) | |||

| - Hearing loss/vertigo | 6 (10.9%) | 5 (29.4%) | |||

| - Migraine | 6 (10.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | n. a. | 0.141 | n. s. |

| - None | 37 (67.3%) | 10 (58.8%) | |||

| - No data | 4 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Age at first symptoms | 47.9 ± 12.6 | 43.1 ± 8.9 | 4.8 (−0.8 to 10.3) | 0.152 | n. s. |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | 20 (36.4%) | 3 (17.6%) | n. a. | 0.234 | n. s. |

| Hearing aid(s) | 20 (36.4%) | 9 (52.9%) | n. a. | 0.265 | n. s. |

| Vegetative symptoms | 47 (85.5%) | 12 (70.6%) | n. a. | 0.277 | n. s. |

| Hydrops grade—median (25th−75th percentiles) | 1.3 (1.0 to 2.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.5) | n. a. | 0.289 | n. s. |

| oVEMP asymmetry ratio | 6.5 ± 24.3 (n = 41) | 13.0 ± 19.4 (n = 13) | 6.5 (−7.1 to 20.0) | 0.324 | n. s. |

| cVEMP asymmetry ratio | 6.9 ± 22.4 (n = 38) | 15.8 ± 22.8 (n = 13) | 8.9 (−0.5 to 14.2) | 0.333 | n. s. |

| Dynamic visual acuity loss (logMAR)—median (25th−75th percentiles) | 0.4 (0.5 to 0.6) (n = 40) | 0.3 (0.4 to 0.6) (n = 7) | n. a. | 0.349 | n. s. |

| Hearing loss (last PTA)—median (25th−75th percentiles) | 40.0 (19.9 to 54.6) | 42.1 (26.8 to 42.1) | n. a. | 0.403 | n. s. |

| Head impulse test gain ratios—median (25th−75th percentiles) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) (n = 49) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) (n = 9) | n. a. | 0.410 | n. s. |

| Neck or spine problems | 9 (16.4%) | 1 (5.9%) | n. a. | 0.434 | n. s. |

| Hearing loss (first PTA)—median (25th−75th percentiles) | 28.3 (10.8 to 45.5) | 28.25 (19.3 to 44.4) | n. a. | 0.443 | n. s. |

| Maximal MD therapy | |||||

| - Betahistine/cinnarizine | 17 (30.9%) | 6 (35.3%) | |||

| - Intratympanic dexamethasone/lidocaine | 34 (61.8%) | 11 (64.7%) | n. a. | 0.665 | n. s. |

| - Intratympanic gentamicin | 4 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Photo-/phono-phobia | 17 (30.9%) | 6 (35.3%) | n. a. | 0.735 | n. s. |

| Hearing loss pattern (first PTA) | |||||

| - Low | 6 (10.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| - High and low (peak) | 25 (45.5%) | 9 (52.9%) | |||

| - High/other | 9 (16.4%) | 3 (17.6%) | n. a. | 0.737 | n. s. |

| - All frequencies | 13 (23.6%) | 5 (29.4%) | |||

| - No hearing loss | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Migraineous aura | 11 (20.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | n. a. | 0.830 | n. s. |

| Maximal migraine therapy | |||||

| - Magnesium, vitamin B2, flunarizine | 13 (23.7%) | 4 (23.5%) | |||

| - Valproate, triptans | 10 (18.1%) | 4 (23.5%) | n. a. | 0.928 | n. s. |

| - None | 32 (58.2%) | 9 (52.9%) | |||

| Hearing loss pattern (last PTA) | |||||

| - Low | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| - High and low | 17 (30.9%) | 6 (35.3%) | |||

| - High/other | 10 (18.2%) | 2 (11.8%) | n. a. | 0.929 | n. s. |

| - All frequencies | 23 (41.8%) | 8 (47.1%) | |||

| - No hearing loss | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| - No data | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (5.9%) | |||

| First MD symptom | |||||

| - Hearing loss | 13 (23.6%) | 4 (23.5%) | |||

| - Vertigo | 11 (20.0%) | 5 (29.4%) | |||

| - Tinnitus/aural fullness | 5 (9.1%) | 1 (5.9%) | n. a. | 0.929 | n. s. |

| - Multiple | 21 (38.2%) | 7 (41.2%) | |||

| - No data | 5 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Allergies | 6 (10.9%) | 2 (11.8%) | n. a. | 0.992 | n. s. |

| Vertigo quality | |||||

| - Rocking | 12 (21.8%) | 4 (23.5%) | |||

| - Spinning | 41 (74.6%) | 13 (76.5%) | n. a. | 1.000 | n. s. |

| - Other | 2 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

Values are reported as absolute numbers (percentage), mean ± SD or median with 25th and 75th percentiles. The number in brackets indicates the number of patients included in the analysis if some patients in the group were excluded. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; cVEMP/oVEMP, cervical/ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials; logMAR, logarithm of minimum angle of resolution; MD, Meniere's disease; n. a., not applicable; n. s., not significant; PTA1, first available pure-tone audiometry; PTA4, last available pure-tone audiometry; SCC, semicircular canal; sig., significant.

Figure 4.

Clinical differences between and within the two MD endotypes. Data from (A–F,H) are also shown in Table 2, data from (G) and (I) were not part of the initial null hypotheses. Bilat, bilateral; contralat, contralateral; EH, endolymphatic hydrops; ipsilat, ipsilateral; MD, Meniere's disease; post, posterior; SCC, semicircular canal; sup, superior; unilat, unilateral; VA, vestibular aqueduct.

Very strong evidence was found for a different sex distribution (p = 0.0004, sig.; Figure 4A), with a strong preponderance of male patients in the MD-hp group (male-to-female ratio = 1:0.06) and a nearly balanced male-to-female ratio in the MD-dg group (1:1.2). The Gd-MRI data strongly evidenced radiological signs of SCC dehiscence (Figure 4B; i.e., no clear spatial separation of signals from the superior, posterior or both SCCs and the cerebrospinal fluid space) more often in the MD-hp group (5/17 [29.4%]) than in the MD-dg group [2/55 [3.6%]; p = 0.007, sig.]. The objective vestibular test data strongly evidenced, on average, greater reductions of bithermal caloric responses (Figure 4C) on the clinically affected side in the MD-dg group (30.2 ± 30.4% asymmetry, n = 48) than in the MD-hp group (13.5 ± 15.2% asymmetry, n = 12; p = 0.009, sig.). Notably, there was no evidence that the mean age at caloric testing differed between groups (MD-dg group: 54.9 ± 13.5 years; MD-hp group 52.4 ± 8.7 years, p = 0.38). We found further evidence for a higher frequency of bilateral clinical manifestations (Figure 4D) in the MD-hp group (5/17 [29.4%]) than in the MD-dg group (3/55 [5.5%]; p = 0.015, sig.), as well as for different frequency patterns of vertigo symptoms (Figure 4E) between groups (p = 0.023, sig.). Post hoc comparisons (Table 3) evidenced a group difference when testing the frequency pattern “monthly” (MD-dg: 12.7%, MD-hp: 41.2% of patients) vs. the other two frequency patterns (“daily/weekly” and “less than once per month”; p = 0.048, Bonferroni corrected). Although the initial analysis revealed no evidence of group differences regarding a positive family history for MD, non-age-related hearing loss or vertigo and migraine (Figure 4F), post hoc analysis for MD and hearing loss/vertigo symptoms only (Table 3) was more prevalent in relatives of MD-hp patients (41.2%; MD-dg group: 15.7%, data available from n = 51; p = 0.028, Bonferroni corrected).

Table 3.

Post-hoc tests.

| ES pathology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical feature | Category | Degeneration | Hypoplasia | p-value (Bonferroni corrected) |

| Vertigo | Monthly | 7 (12.7%) | 7 (41.2%) | p = 0.048 |

| Daily/weekly or less than once per month | 48 (87.3%) | 10 (58.8%) | ||

| Headache type (males) | Migraineous | 6 | 4 | p = 0.211 |

| Non-migraineous | 5 | 7 | ||

| Other | 14 | 5 | ||

| Family history | MD, hearing loss and/or vertigo | 8 (15.7%) | 7 (41.2%) | p = 0.028 |

| No family history | 43 (84.3%) | 10 (58.8%) | ||

For the remaining variables, no evidence of group differences was found, or no statistical analysis was performed. Those variables nonetheless represent clinically meaningful and potentially endotype-segregating features (see Discussion section). Although strong evidence suggested that headache symptom frequencies differed between the two groups in the primary statistical analysis (p = 0.004, sig., Table 2), post hoc analysis (Table 3) revealed no evidence of a group difference when only male patients in both groups were compared to eliminate sex as a confounding factor [higher prevalence of migraine headaches in women than in men in the general population (23)]. In the MD-hp group, unilateral hypoplastic ES pathology was invariably associated with ipsilateral endolymphatic hydrops and ipsilateral MD. However, among the eight patients with bilateral ES hypoplasia, five demonstrated endolymphatic hydrops and MD symptoms in both inner ears, while three had only one ear affected (Figure 4G). The mean age when MD symptoms first manifested was slightly earlier in the MD-hp group (43.1 ± 8.9 years) than in the MD-dg group (47.9 ± 12.6 years; p = 0.152, n. s.; Figure 4H). Endolymphatic hydrops without evidence of clinical affection [i.e., “clinically silent” endolymphatic hydrops (8, 24)] was exclusively observed in the contralateral inner ears from unilaterally affected MD-dg patients (19.2% of patients; p = 0.186, n. s.; Figure 4I).

Discussion

The following sections discuss the endotype-specific clinical characteristics and their potential implications for clinically managing MD patients (synopsis in Table 4).

Table 4.

Endotype-specific clinical considerations.

| Endotype (patient subgroup) | Laterality | Endotype frequency | Characteristics/considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES hypoplasia (MD-hp patients) | Overall | 23.6% |

|

| Unilateral | 16.7% |

|

|

| Bilateral | 6.9% |

|

|

| ES degeneration (MD-dg patients) | Overall | 76.4% |

|

| Unilateral | 72.2% |

|

|

| Bilateral | 4.2% |

|

Considering the anticipated low chance of intraoperatively identifying the operculum (25).

equal to the overall risk of developing MD with degenerative ES pathology in the general population [i.e., 0.15% based on the MD prevalence of 0.2% (26) and a prevalence of degenerative ES pathology of 76.4% among MD patients in the present study].

upon initial presentation with clinically unilateral symptoms.

Endotype “ES Hypoplasia” (MD-hp Subgroup)

ES hypoplasia was present in 23.6% of our cohort. Unilateral ES hypoplasia was invariably associated with ipsilateral endolymphatic hydrops and MD but not with any radiological/clinical signs for contralateral affection. In those cases, the risk of developing MD in the contralateral inner ear (normal VA angle) is probably low, most likely comparable to the risk of MD with an ES degenerative endotype in the general population [i.e., ~0.15% per a calculation based on data from this study and (26)], and they may be suitable candidates for ablative therapies [e.g., gentamicin injections) in the affected ear if clinically indicated. MD-hp patients should be considered with caution for ES surgical procedures [decompression, shunting, or endolymphatic duct blockage; reviewed in (28, 29)] since the hypoplastic operculum of the VA is considerably smaller than normal, and the extraosseous ES portion is mostly absent (6). A recent retrospective study showed that during ES surgery in MD patients, intraoperatively visualizing the operculum was impossible in 28% of the cases (25). This number very closely matches the hypoplastic ES-endotype prevalence found in the present study (23.6%). In almost all MD-hp patients, bilateral ES hypoplasia was associated with bilateral endolymphatic hydrops and MD; however, three of those patients showed only unilateral hydrops and clinical symptoms at the time of data collection (Figure 4G). These three patients are expected to develop bilateral MD later in life based on the consistent association between ES hypoplasia and clinical symptoms that we found previously in post-mortem cases (6, 7). Thus, in all MD-hp patients with bilateral ES hypoplasia, a bilaterally impaired audiovestibular function (bilateral MD) with a significantly impacted quality of life should be expected, and those patients should be considered with caution for ablative therapies. Furthermore, MD-hp patients may have an increased risk of concomitant audiovestibular symptoms caused by SCC dehiscence syndrome, as suggested by the higher prevalence (29.4%) of suspected (posterior) SCC dehiscence on the MRI data. In contrast, SCC dehiscence was suspected radiologically in only 3.6% of MD-dg patients, mostly of the superior SCC, which is comparable to the reported overall prevalence of superior SCC dehiscence in the general population [3–10% (30–32)]. The epidemiological features associated with this endotype (predominantly men, familial clustering of MD, and tendency toward earlier disease onset) support the hypothesis of a genetic/developmental cause. Therefore, the endotype's specific radiological feature (VA bending angle ≥140°) may be useful for predictive clinical screenings (e.g., in family members of MD-hp patients) for this potentially inheritable inner ear pathology and to prognosticate the risk of developing MD.

Endotype “ES Degeneration” (MD-dg Subgroup)

ES degeneration was observed in 76.4% (n = 55; MD-dg group) of patients. This endotype (VA angle ≤120°) is radiologically diagnosed by excluding the hypoplastic endotype (VA angle ≥140°), but it cannot be distinguished from a normal ES (VA angle ≤120°) using the Gd-MRI-based criteria described herein. Thus, in contrast to the hypoplastic endotype, no potential prognostic marker for future bilateral manifestation is available to date. This endotype was exclusively associated with contralateral “clinically silent” endolymphatic hydrops (i.e., hydrops without clinical signs of inner ear dysfunction, particularly without MD). Clinically silent hydrops was observed in 19.2% of all unilateral MD-dg patients, which is consistent with previously reported numbers from MRI studies investigating unilaterally affected MD patients [16.0–23.3% (8, 33)]. Since clinically silent hydrops reportedly progresses to MD in 33% of cases (34), MD-dg patients with contralateral hydrops may have an elevated risk of developing bilateral MD and should be considered for ablative therapy with caution. However, MD-dg patients may be generally considered suitable candidates for ES surgery (decompression or shunting) since the operculum, which exhibits normal anatomy in these cases, allows its reliable intraoperative visualization. However, per our previous human pathology study (6), the extraosseous ES portion is degenerating in these cases, which calls into question the proposed mode of function of these treatments. On average, a higher frequency of vertigo attacks and a more severely impaired vestibular (caloric) function was associated with this endotype. These findings may be explained by a supposedly more sudden manifestation of ES degeneration in the matured inner ear, as opposed to the developmentally inherent ES hypoplasia. ES degeneration therefore probably has a more disruptive effect on vestibular function due to the adult inner ear's limited capability to develop compensating homeostatic mechanisms. In contrast in the developing inner ear, in the presence of ES hypoplasia, such compensatory function may be established more efficiently.

Between-Endotype Comparisons With Little or No Evidence for Group Differences

Of the 28 tested clinical variables, we found weak to no evidence for endotype differences for 21 variables (Table 2) and for a longitudinal analysis of hearing loss progression (Supplementary Figure 1; Benjamini-Hochberg significance: n. s.). However, our retrospective explorative approach does not categorically rule out those 21 variables as clinically meaningful, endotype-segregating features. Specifically, variables such as migraine headache prevalence, age at first MD symptom onset, and prevalence of “clinically silent” contralateral endolymphatic hydrops should, in our view, remain of interest in future endotyping studies.

Although the migraine headache prevalence did not differ between endotypes, the overall prevalence of migraine symptoms in our cohort (59.9%) was similar to that of a previous study [56% (35)] and considerably higher than the prevalence in the general population [11–18% (36–38)]. Future studies should more specifically address questions such as whether migraines are associated—or even share a common etiopathology—with a distinct MD endotype.

An earlier age of onset of the first MD symptoms in MD-hp patients was evident in our previous temporal bone study (6) (MD-hp: 37.7 ± 19.0 years; MD-dg: 58.1 ± 20.5 years; p = 0.038) but not in the present study (MD-hp: 43.1 ± 8.9 years; MD-dg: 47.9 ± 12.6; p = 0.152, n. s.). An earlier symptom onset in the MD-hp group (although not evident in the present study) could be explained by the likely prenatally determined hypoplastic ES pathology (7), which presumably renders the inner ear susceptible to precipitating factors that ultimately cause MD. In contrast, ES degeneration in MD-dg patients is thought to be an acquired pathology, possibly associated with age-related factors, and therefore may explain MD's tendency to manifest later in life.

A “clinically silent” (no MD symptoms) endolymphatic hydrops is a frequent [5–26%, (8, 24, 39)] histological and radiological entity in the contralateral ears from unilaterally affected Meniere's patients, and was in the present study found exclusively in the MD-dg endotype (19.2%; p = 0.186, n. s.). The frequent association of this endotype with bilateral hydrops may suggest limited or still progressing ES degeneration as the cause for contralateral, clinically silent hydrops, and further suggests a systemic (e.g. immune-mediated or vascular) etiology of degenerative ES pathology. Although progression to bilateral MD was rarely observed in the MD-dg group (4.2%); longer prospective observations are required to determine whether clinically silent hydrops represents a precursor lesion of MD.

Patient Subgrouping Approaches in MD

Patient stratification algorithms in MD can be divided into phenomenology (clinical features)-based “top-down” algorithms, and etiology (endotype)-based ”bottom-up” algorithms. Frejo et al. used disease laterality (uni vs. bilateral) as a principal group classifier, and, in a second step, applied data mining procedures (cluster analysis) to identify clinical features (autoimmune disorders, migraine, MD family history, synchronic vs. metachronic onset of hearing loss) that segregated five discrete subgroups of uni and bilateral MD patients, respectively (40, 41). In a follow-up study, Frejo et al. then used an etiology-based approach and distinguished two subgroups with different cytokine profiles among uni and bilateral MD patients (42). They suggested an immune-mediated etiology in the subgroup that exhibited elevated interleucin-1β plasma levels as well as mold-induced TNF-α secretion. Notably, some subgroups defined by Frejo et al. share certain group-defining features with the MD-dg and MD-hp endotypes. Further studies that combine the described subgrouping/endotyping algorithms will determine whether the subgroups defined by the different approaches truly overlap.

Limitations of the Study

The overall study design was retrospective and exploratory. Thus, for statistical between-group comparisons, an FDR was chosen that allowed us to identify many endotype-specific clinical features. Moreover, few patients (n = 72) were available for this study. Consequently, the statistical power for some group comparisons was low, and the results from this investigation should be verified in a larger prospective cohort study.

For the 20 excluded patients, αexit angles between 120 and 140° were measured, or the VA could not be visualized (Figure 1). Since such αexit values or non-visualization of the VA were lacking in a previous retrospective MD case series (n = 64) in which HRCT temporal bone data were measured (7), we consider this a problem of insufficient Gd-MRI resolution, likely due to movement artifacts in individual datasets.

For most included patients, the initial diagnostic test data (PTA, vestibular diagnostics) were acquired at the time of diagnosis, whereas for a minority of patients, these initial tests were performed several months or years after being diagnosed. This inhomogeneity of the available data is a confounding factor, particularly in the longitudinal analysis of hearing thresholds (Supplementary Figure 1).

Conclusion

This novel endotype-driven diagnostic approach allowed distinguishing clinically meaningful MD patient subgroups with different etiologies and phenotypes. This approach may (i) help select more homogeneous patient cohorts for future clinical studies, (ii) refine clinical diagnoses, (iii) improve clinical decision-making, and (iv) help prognosticate the disease course in individual patients. The results from this retrospective study require validation in prospective cohort studies.

Author Contributions

AE: study conception and design; DB, CB, TH, and AE: data acquisition; DB, CB, TH, EM, SM, and AE: data analysis and interpretation; DB and AE: drafted the manuscript; AM, VW, SM, and BS: critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Niels Hagenbuch for biostatistical support.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by a principal grant from the British Ménière's Society. DB was supported by a national M.D.-Ph.D. scholarship of the Swiss National Science Foundation. AE was supported by a career development grant from the University of Zurich.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00303/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Rauch S. Clinical hints and precipitating factors in patients suffering from Meniere's disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. (2010) 43:1011–17. 10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friberg U, Stahle J, Svedberg A. The natural course of Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. (1984) 406:72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gürkov R, Jerin C, Flatz W, Maxwell R. Clinical manifestations of hydropic ear disease (Menière's). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2018) 276:27–40. 10.1007/s00405-018-5157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merchant SN, Rauch SD, Nadol JBJ, Nadol JB, Jr. Meniere's disease. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (1995) 252:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahara M. Bilateral aspects of meniere's disease: Meniere's disease with bilateral fluctuant hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. (1991) 485:74–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckhard AH, Zhu M, O'Malley JT, Williams GH, Loffing J, Rauch SD, et al. Inner ear pathologies impair sodium-regulated ion transport in Meniere's disease. Acta Neuropathol. (2019) 137:343–57. 10.1007/s00401-018-1927-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bächinger D, Luu N-N, Kempfle JS, Barber S, Zürrer D, Lee DJ, et al. Vestibular aqueduct morphology correlates with endolymphatic sac pathologies in Meniere's disease – a correlative histology and computed tomography study. Otol Neurotol. (in press). 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baráth K, Schuknecht B, Monge Naldi A, Schrepfer T, Bockisch CJ, Hegemann SCA. Detection and grading of endolymphatic hydrops in meniere disease using MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. (2014) 35:1387–92. 10.3174/ajnr.A3856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsell M, Balkany TA, Gates GA, Goldenberg RA, William L, House JW. Committee on hearing and equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Menière's disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Foundation, Inc. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (1995) 113:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchant SN, Nadol JB. Schuknecht's Pathology of the Ear. 3rd ed Shelton, CT: People's Medical Publishing House-USA; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naganawa S, Ishihara S, Iwano S, Sone M, Nakashima T. Three-dimensional (3D) visualization of endolymphatic hydrops after intratympanic injection of Gd-DTPA: optimization of a 3D-real inversion-recovery turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequence and application of a 32-channel head coil at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging. (2010) 31:210–14. 10.1002/jmri.22012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zürrer D. CoolAngleCalc. Available online at: https://danielzuerrer.github.io/CoolAngleCalcJS/ (accessed January 20, 2019).

- 13.Landis JR, Koch GG. Agreement measures for categorical data. Biometrics. (1977) 33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bland JM. An Introduction to Medical Statistics. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. (1995) 57:289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3rd ed Baltimore, MA: Sparky House Publishing; (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linnstaedt SD, Walker MG, Parker JS, Yeh E, Sons RL, Zimny E, et al. MicroRNA circulating in the early aftermath of motor vehicle collision predict persistent pain development and suggest a role for microRNA in sex-specific pain differences. Mol Pain. (2015) 11:66. 10.1186/s12990-015-0069-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrario M, Cambiaghi A, Brunelli L, Giordano S, Caironi P, Guatteri L, et al. Mortality prediction in patients with severe septic shock: a pilot study using a target metabolomics approach. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:20391. 10.1038/srep20391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald PL, Gardner RC. Type I error rate comparisons of post hoc procedures for I × J chi-square tables. Educ Psychol Meas. (2000) 60:735–54. 10.1177/00131640021970871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Foundation for Statistical Computing . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2011). 30628467 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates D, Maechler M. Package “Lme4” (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. (2012) 30:1323–41. 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache. (2013) 53:427–36. 10.1111/head.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauch SD, Merchant SN, Thedinger BA. Meniere's syndrome and endolymphatic hydrops. Double-blind temporal bone study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. (1989) 98:873–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitahara T, Yamanaka T. Identification of operculum and surgical results in endolymphatic sac drainage surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. (2017) 44:116–18. 10.1016/j.anl.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander TH, Harris JP. Current epidemiology of Meniere's syndrome. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. (2010) 43:965–70. 10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirsh ER, Kozin ED, Knoll RM, Wong K, Faquin W, Reinshagen KL, et al. Sequential imaging in patient with suspected Menière's disease identifies endolymphatic sac tumor. Otol Neurotol. (2018) 39:e856–9. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pullens B, Verschuur HP, van Benthem PP. Surgery for Ménière's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 2:CD005395 10.1002/14651858.CD005395.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sood AJ, Lambert PR, Nguyen SA, Meyer TA. Endolymphatic sac surgery for Ménière's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. (2014) 35:1033–45. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crovetto M, Whyte J, Rodriguez OMM, Lecumberri I, Martinez C, Eléxpuru J. Anatomo-radiological study of the Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence. Eur J Radiol. (2010) 76:167–72. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stimmer H, Hamann KF, Zeiter S, Naumann A, Rummeny EJ. Semicircular canal dehiscence in HR multislice computed tomography: distribution, frequency, and clinical relevance. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2012) 269:475–80. 10.1007/s00405-011-1688-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi WL, Brewster R, Poe D, Vernick D, Lee DJ, Eduardo Corrales C, et al. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome. J Neurosurg. (2017) 72:1–9. 10.3171/2016.9.JNS16503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H. Endolymphatic hydrops detected by 3-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI following intratympanic injection of gadolinium in the asymptomatic contralateral ears of patients with unilateral Ménière's disease. Med Sci Monit. (2015) 21:701–7. 10.12659/MSM.892383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.House JW, Doherty JK, Fisher LM, Derebery MJ, Berliner KI. Meniere's disease: prevalence of contralateral ear involvement. Otol Neurotol. (2006) 27:355–61. 10.1097/00129492-200604000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radtke A, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H. Migraine and Ménière's disease: is there a link? Neurology. (2002) 59:1700–4. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000036903.22461.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J. Epidemiology of headache in a general population-a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol. (1991) 44:1147–57. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90147-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goebel H, Petersen-Braun M, Soyka D. The epidemiology of headache in Germany: a nationwide survey of a representative sample on the basis of the headache classification of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia. (1994) 14:97–106. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1994.1402097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Launer LJ, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD. The prevalence and characteristics of migraine in a population-based cohort: the GEM Study. Neurology. (1999) 53:537–42. 10.1212/WNL.53.3.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB. Pathophysiology of Meniere's syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol. (2005) 26:74–81. 10.1097/00129492-200501000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frejo L, Soto-Varela A, Santos-Perez SS, Aran I, Batuecas-Caletrio A, Perez-Guillen V, et al. Clinical subgroups in bilateral meniere disease. Front Neurol. (2016) 7:182 10.3389/fneur.2016.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frejo L, Martin-Sanz E, Teggi R, Trinidad G, Soto-Varela A, Santos-Perez S, et al. Extended phenotype and clinical subgroups in unilateral Meniere disease: a cross-sectional study with cluster analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. (2017) 42:1172–80. 10.1111/coa.12844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frejo L, Gallego-Martinez A, Requena T, Martin-Sanz E, Amor-Dorado JC, Soto-Varela A, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines and response to molds in mononuclear cells of patients with Meniere disease. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:5974. 10.1038/s41598-018-23911-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.