Plants grow continuously, forming new meristem-derived organs and tissues throughout their post-embryonic life. As sessile organisms, plants need to constantly integrate and reflect environmental fluctuations in their growth and development, which can translate into high level of developmental plasticity in response to environmental changes (Gaillochet and Lohmann, 2015). Alternatively, variable environments can select for robustness, where organisms function across a wide range of conditions with little change in phenotype. Plant growth is then governed by complex interplay of phytohormone signaling, chromatin structure remodeling and gene expression reprogramming. How these regulatory levels are interconnected remains largely enigmatic, but mechanistic evidence of crosstalk between phytohormone signaling and chromatin organization is emerging.

Here we review (1) evidences of molecular mechanisms that mediate the crosstalk between phytohormone signaling, chromatin structure and gene expression (2) how this crosstalk may link to plant developmental plasticity and robustness and finally (3) why meristems may represent central places for this crosstalk allowing plasticity and environmental memory.

Crosstalk Mechanisms: A Chicken-and-Egg Situation

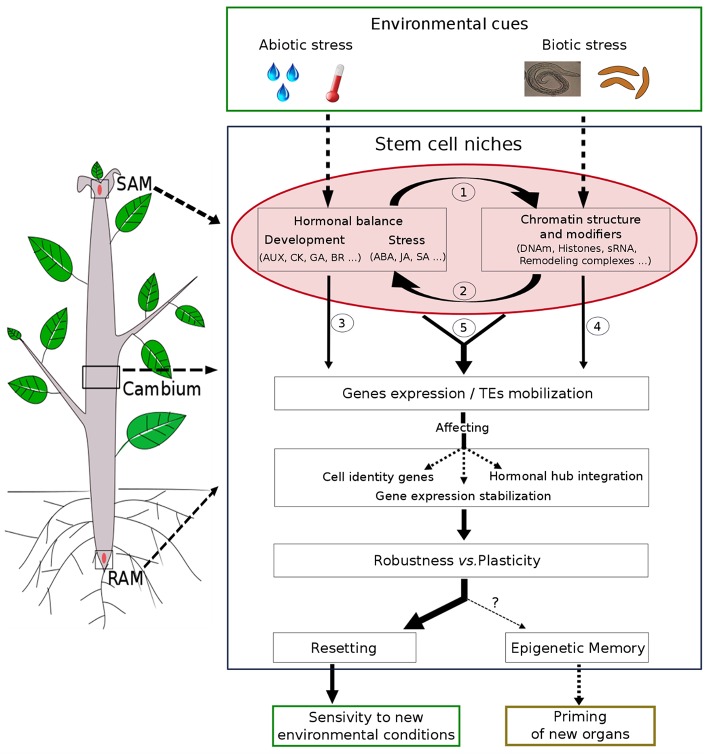

Phytohormone and epigenetic regulation can interact on multiple levels (Figure 1): (1) phytohormone signaling directly affects expression or activity of key chromatin modifiers, (2) chromatin machinery target genes of the phytohormone metabolic/signaling pathways, (3) both players interact on genes involved in developmental or stress responses.

Figure 1.

Schematic model of phytohormones and chromatin crosstalk during plant developmental plasticity and robustness. Stem cell niches in SAM, RAM, or cambium are center of morphogenesis giving rise to the aerial and root systems or wood formation in perennials and plasticity in response to various environmental cues. Environmental signals are perceived directly or indirectly by meristems and could affect hormonal balance and/or chromatin structure in a complex crosstalk: (1) hormones can alter chromatin structure and modifiers or (2) chromatin can regulate hormones signaling/biosynthesis. These two mechanisms could then interact separately (3 and 4), jointly or successively (5) affecting genes expression and /or TEs mobilization. Thus, the hormone/chromatin crosstalk can participate in developmental choice (Robustness vs. Plasticity) by controlling cell gene identity in meristems, hormone balance integration, or chromatin stabilization of gene expression. While most of these changes are transient (resetting of hormonal and chromatin modifications) allowing the plant to be respond to new environmental conditions, chromatin states could be maintained through cell division allowing an epigenetic memory and a potential priming of new meristem-derived-organs.

Several examples show that components of phytohormone signaling pathways directly control the activity of key chromatin modifiers such as POLYCOMB REPRESSIVE COMPLEX (PRC) 1 and 2 with histone-methyltransferase activity playing a major role in transcriptional regulation during development (Bratzel et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2010, 2016; Ikeuchi et al., 2015; Mozgová et al., 2017). For example, the brassinosteroid (BR) signaling TFs BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) recruits the H3K27me3-demethylase EARLY FLOWERING (ELF) 6 to antagonize the H3K27me3-activity of PRC2, a chromatin modifier, at the flowering repressor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), preventing precocious floral transition (Yu et al., 2008; Li et al., 2018). Additionally, chromatin complexes can be post-translationally modified by components of phytohormone signaling pathways that influence their activity. For example, abscisic acid (ABA) signaling induces SnRK-mediated phosphorylation of the chromatin remodeling ATPase BRAHMA (BRM), inhibiting its repressive activity at ABA-responsive genes (Peirats-Llobet et al., 2016). These examples demonstrate that activity of chromatin modifiers can be directed to specific loci or directly modulated by phytohormone signaling cascades.

Another possibility is that changes in chromatin structure control phytohormone biosynthesis, signaling and response. Variation in DNA methylation in response to water availability in poplar or among Arabidopsis epigenetic recombinant inbred lines (epiRILs) is associated with changes in jasmonic (JA), salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene responses (Latzel et al., 2012; Lafon-Placette et al., 2018). Similarly, rice plants with reduced H3K27me3 exhibit significant differences in the auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellin (GA), ABA, JA, and SA content (Liu et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these effects may be pleiotropic and may reflect altered general physiological states. As more direct evidence, PRC2 activity in Arabidopsis seed coat is downregulated by fertilization-dependent auxin, and is required for repressing GA production prior to fertilization, mediating the crosstalk between two phytohormonal pathways (Figueiredo et al., 2015, 2016; Figueiredo and Köhler, 2018). PRC2 also represses auxin biosynthesis and signaling genes in the SAM and leaves of Arabidopsis (Lafos et al., 2011). Conversely, in the RAM, the expression of the auxin efflux carrier-encoding PIN-FORMED (PIN) genes is positively regulated by BRM establishing local auxin maxima and stimulating the expression of the RAM-specifying PLETHORA genes PLT1 and PLT2 (Yang et al., 2015). BRM also binds to GA-related genes to stimulate GA biosynthesis and signaling (Archacki et al., 2013).

Apart from biosynthesis and signaling, phytohormone-response genes are under direct control of chromatin modifiers. Initially described as involved in auxin homeostasis (Sorin et al., 2005), the ARGONAUTE protein AGO1, guided by small RNAs and associating with SWI/SNF complexes, was recently described to bind genes activated upon JA, auxin, and SA stimuli in Arabidopsis (Liu C. et al., 2018). ABA-responsive genes in Arabidopsis are repressed by histone deacetylation (Perrella et al., 2013) through the action of MULTICOPY SUPRESSOR OF IRA (MSI) 1 recruiting the HISTONE DEACETYLASE (HDA)19 (Alexandre et al., 2009; Mehdi et al., 2016) and also by BRM-mediated chromatin remodeling (Han et al., 2012). Significantly, expression of 80% GA–responsive genes relies on the chromatin remodeler PICKLE (PKL) (Park et al., 2017). Consequently, plants with reduced MSI1, HDA19, or BRM levels are more sensitive to ABA, display ABA-dependent growth defects and higher tolerance to drought, and absence of PKL results in GA-reversible root swelling and embryonic lipid accumulation (Ogas et al., 1997) demonstrating the developmental importance of chromatin modifiers in phytohormone-mediated responses.

Hormone Signaling and Chromatin Crosstalk can Participate in Plasticity and Robustness

Hormone signaling and chromatin crosstalk can participate in developmental paths by distinct ways: (1) control of cell identity genes in meristems, (2) chromatin-mediated stabilization of gene expression beyond the hormonal initial signal, (3) chromatin-governed integration of separate hormone signaling pathways.

Chromatin-modifying complexes target key phytohormone-regulated genes that specify meristem cell identity and whose ectopic expression can result in cell reprogramming and homeosis (Zuo et al., 2002; Galinha et al., 2007). For example, the SAM-organizing homeobox gene WUSCHEL (WUS) is regulated by cytokinin signaling, DNA methylation, H3K27me, or chromatin remodeling (Kwon, 2005; Dodsworth, 2009; Cao et al., 2015; Liu H. et al., 2018), and loss of DNA methylation in WUS promoter is connected to in-vitro shoot initiation induced by cytokinin (Li et al., 2011). Other stem cell niche-defining TFs such as WOX4, WOX5, PLT1, or PLT2 are potential PRC2 targets (Oh et al., 2008; Lafos et al., 2011). Co-expression of these TFs can be triggered by environmental and hormone cues or ectopically induced in PRC2-depleted plants, resulting in cell reprogramming (Chanvivattana et al., 2004; Barrero et al., 2007; Ikeuchi et al., 2015; Mozgová et al., 2017). Increased or dispersed expression of cell identity-defining TFs and change and/or loss of cell identity also occurs in mutants of chromatin modifiers such as the repressive H2A-ubiquitinase complex PRC1 (Xu and Shen, 2008; Bratzel et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2010, 2016), histone deacetylases HDA6 and HAD19 (Tanaka et al., 2008; Pi et al., 2015), PKL (Ogas et al., 1999) or replication-dependent H3/H4 chaperone CHROMATIN ASSEMBLY COMPLEX (CAF)-1 (Kaya et al., 2001). Thus, chromatin structure appears to restrict expression of developmental genes to retain cell identities. Similarly, repression of ABA response by several chromatin modifiers (MSI1, HDA19, BRM) could act to prevent an ectopic stress response in favorable environmental conditions.

Chromatin structure may stabilize gene expression state beyond the duration of the environmental or phytohormone stimulus. An example is the cold-induced establishment of H3K27me3 at FLC during vernalization that is stable through mitosis, providing an in-cis memory system of FLC repression even after transfer to warmth (Berry et al., 2015; Hepworth and Dean, 2015). Persistent H3K4me2/3, H3/H4ac or local nucleosome depletion are found at genes primed for biotic or abiotic stress responses including priming by phytohormones or their analogs (Jaskiewicz et al., 2011; Lämke and Bäurle, 2017; Laura et al., 2018; Liu H. C. et al., 2018) demonstrating that also “accessible” chromatin structure contributes to mitotic memory (Figure 1).

Chromatin-modifying proteins may also serve as integrators defining the final outcome of interplay of various hormone signaling pathways. Phytohormone-induced change of chromatin structure may rely on multiple different chromatin modifiers as is exemplified by modulators of ABA signaling. A single chromatin modifier can also be implicated in responses to different hormones, as is exemplified by BRM (Sarnowska et al., 2016). Chromatin can thus provide a robust hub integrating different incoming cues while potentiating the persistence of the gene expression patterns through its stability during mitotic cell divisions.

Meristems are Central Places for Phytohormone Chromatin Crosstalk

The biological significance of the crosstalk in meristems is supported by (1) their central role in postembryonic morphogenesis, plasticity and memory, (2) their particularities for phytohomone signaling and chromatin remodeling, (3) first evidences reported for this crosstalk in SAM.

The meristems represent major sites of stem cell niches in plants (Scheres, 2007; Tucker and Laux, 2007; Aichinger et al., 2012). Apical meristems, together with the secondary meristem, the cambium, have the capacity to maintain and self-renew populations of undifferentiated cells, underlying continuous post-embryonic organ development modulated by environmental conditions (Figure 1; Gaillochet and Lohmann, 2015; Pavlovic and Radotic, 2017; Xiao et al., 2017). The SAM is also the place of epigenetic memory as reported for vernalization and some priming effects (Hepworth and Dean, 2015; Lämke and Bäurle, 2017).

Phytohormone and epigenetic pathways play overlapping/complementary roles in meristem functions and developmental plasticity or robustness, laying the basis for a biologically significant crosstalk. Importantly, meristems have been shown to be the place of epigenetic control for stem cell pluripotency, differentiation, and reprogramming (Cao et al., 2015; Gaillochet and Lohmann, 2015; Pi et al., 2015; Morao et al., 2016; Ojolo et al., 2018) whose epigenetic setup may differ from the surrounding tissues (Yadav et al., 2009; Baubec et al., 2014).

Major evidence for phytohormone-chromatin crosstalk was obtained using Arabidopsis mutants, or applying phytohormones or chemical inhibitors of chromatin modifiers in various developmental processes (Yamamuro et al., 2016; Campos-Rivero et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2018; Ojolo et al., 2018; Wakeel et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2018). Only a few reports highlight potential crosstalk directly in the meristems as exemplified by PRC2 repressing particular PIN genes (auxin transporters) in the SAM of Arabidopsis clv3 mutants (Lafos et al., 2011). Recent studies in vernalized sugar beet (Hébrard et al., 2016) and in poplar under drought or cold exposure (Conde et al., 2017; Lafon-Placette et al., 2018; Le Gac et al., 2018) have recently shown that differentially expressed genes under DNA methylation control in SAM correspond to a limited developmental gene network mainly involved in growth and phytohormone pathways such as jasmonate activators and ethylene repressors. Indeed, Le Gac et al. (2018) show that hormone-related epigenome reprogramming in the SAM of poplar hybrids is stable for at least several months after the stress period in winter-dormant SAM providing evidence of an environmental epigenetic memory. Recently, this phenomenon was also described in the SAM of natural populations of black poplar under drought conditions (Sow et al., 2018a). Similarly, support for epigenetic memory of climatic conditions is found in Norway spruce trees grown from somatic embryos produced at different temperatures (Yakovlev et al., 2011, 2016). Considering the absence of post-embryonic organs, the SAM could play a major role in the transmission of the environmentally-established chromatin states during early development.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

In conclusion, phytohormone action and chromatin modifiers seem to be tightly interacting but the extent to which they act jointly or independently remains unclear (Ojolo et al., 2018). However, the multi-layered control of local chromatin structure in response to hormonal cues may provide an important hub that integrates the incoming cues, conferring developmental robustness while retaining a sufficient potential for gene transcription change, stabilization and phenotypic plasticity (Lachowiec et al., 2016).

Current knowledge leads to the opinion that this crosstalk in meristems can integrate environmental cues for developmental outcome. Erasure of this signaling may allow continuous adjustment to new environmental conditions. Its maintenance through persistent chromatin states can however stimulate mitotic memory that could prime later organ formation. How the balance between erasure and memory is achieved remains enigmatic (Figure 1).

While the mechanistic events could be more easily deciphered in well-established model annuals such as Arabidopsis, it is important to establish perennial models where the impact of mitotic epigenetic memory is of importance in the context of climate change. In addition to SAM and RAM, cambium, whose activity is crucial for environmentally controlled wood formation, may be an appropriate and highly relevant model (Wang et al., 2016; Oles et al., 2017; Figure 1). Deciphering this crosstalk in the meristems requires improving single-cell methodologies to study the dynamics of chromatin structure in response to complex phytohormone-associated environmental and developmental responses and its memory. Exploiting epigenetic variation and the potential to derive primed plants from meristem regeneration or somatic embryos (Achour et al., 2017; Gallusci et al., 2017; Springer and Schmitz, 2017; Sow et al., 2018b) seems also promising.

Author Contributions

SM suggested and designed the opinion article. MDS and SM designed the Figure 1. IM and SM finalized and revised the article. All the authors checked and confirmed the final version of the manuscript. All the authors drafted the entire manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Dr. Nicolas Bouché (INRA Versailles, France) for carefully reading the manuscript before submission. We apologize to all colleagues whose work was not cited due to length limitations.

Footnotes

Funding. MDS and JG received Ph.D. grants from the Ministère de la Recherche et Enseignement Supérieur and INRA—Région Bretagne, respectively. This work was funded by the ANR France, within the project EPITREE (ANR-17-CE32-0009-01) to SM and by the Czech Science Foundation (GACR 16-08423Y) to IM.

References

- Achour Z., Archipiano M., Barneche F., Baurens C., Beckert M., Ben C., et al. (2017). Epigenetics in plant breeding, in Article de positionnement du Groupement d'intérêt scientifique Biotechnologies vertes et de l'Alliance nationale de recherche pour l'environnement. Available online at: www.gisbiotechnologiesvertes.com/fr/publications/position-paper-epigenetics-in-plant-breeding (accessed February 13, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Aichinger E., Kornet N., Friedrich T., Laux T. (2012). Plant stem cell niches. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 615–636. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C., Möller-Steinbach Y., Schönrock N., Gruissem W., Hennig L. (2009). Arabidopsis MSI1 is required for negative regulation of the response to drought stress. Mol. Plant 2, 675–687. 10.1093/mp/ssp012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archacki R., Buszewicz D., Sarnowski T. J., Sarnowska E., Rolicka A. T., Tohge T., et al. (2013). BRAHMA ATPase of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex acts as a positive regulator of gibberellin-mediated responses in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 8:e58588. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrero J. M., Gonzalez-Bayon R., del Pozo J. C., Ponce M. R., Micol J. L. (2007). INCURVATA2 encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase and interacts with genes involved in chromatin-mediated cellular memory in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19, 2822–2838. 10.1105/tpc.107.054130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubec T., Finke A., Mittelsten Scheid O., Pecinka A. (2014). Meristem-specific expression of epigenetic regulators safeguards transposon silencing in Arabidopsis. EMBO Rep. 15, 446–452. 10.1002/embr.201337915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry S., Hartley M., Olsson T. S. G., Dean C., Howard M. (2015). Local chromatin environment of a Polycomb target gene instructs its own epigenetic inheritance. ELife 4:e07205. 10.7554/eLife.07205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratzel F., López-Torrejón G., Koch M., Del Pozo J. C., Calonje M. (2010). Keeping cell identity in Arabidopsis requires PRC1 RING-finger homologs that catalyze H2A monoubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 20, 1853–1859. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Rivero G., Osorio-Montalvo P., Sánchez-Borges R., Us-Camas R., Duarte-Aké F., De-la-Pe-a C. (2017). Plant hormone signaling in flowering: an epigenetic point of view. J. Plant Physiol. 214, 16–27. 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., He Z., Guo L., Liu X. (2015). Epigenetic mechanisms are critical for the regulation of WUSCHEL expression in floral meristems: figure 1. Plant Physiol. 168, 1189–1196. 10.1104/pp.15.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanvivattana Y., Bishopp A., Schubert D., Stock C., Moon Y.-H., Sung Z. R., et al. (2004). Interaction of Polycomb-group proteins controlling flowering in Arabidopsis. Development 131, 5263–5276. 10.1242/dev.01400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Molitor A., Liu C., Shen W.-H. (2010). The Arabidopsis PRC1-like ring-finger proteins are necessary for repression of embryonic traits during vegetative growth. Cell Res. 20, 1332–1344. 10.1038/cr.2010.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Molitor A. M., Xu L., Shen W.-H. (2016). Arabidopsis PRC1 core component AtRING1 regulates stem cell-determining carpel development mainly through repression of class I KNOX genes. BMC Biol. 14:112. 10.1186/s12915-016-0336-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde D., Le Gac A.-L., Perales M., Dervinis C., Kirst M., Maury S., et al. (2017). Chilling-responsive DEMETER-LIKE DNA demethylase mediates in poplar bud break: Role of active DNA demethylase in trees' bud break. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 2236–2249. 10.1111/pce.13019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodsworth S. (2009). A diverse and intricate signalling network regulates stem cell fate in the shoot apical meristem. Dev. Biol. 336, 1–9. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo D. D., Batista R. A., Roszak P. J., Hennig L., Köhler C. (2016). Auxin production in the endosperm drives seed coat development in Arabidopsis. ELife 5:e20542. 10.7554/eLife.20542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo D. D., Batista R. A., Roszak P. J., Köhler C. (2015). Auxin production couples endosperm development to fertilization. Nat. Plants 1:15184. 10.1038/nplants.2015.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo D. D., Köhler C. (2018). Auxin: a molecular trigger of seed development. Genes Dev. 32, 479–490. 10.1101/gad.312546.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillochet C., Lohmann J. U. (2015). The never-ending story: from pluripotency to plant developmental plasticity. Development 142, 2237–2249. 10.1242/dev.117614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinha C., Hofhuis H., Luijten M., Willemsen V., Blilou I., Heidstra R., et al. (2007). PLETHORA proteins as dose-dependent master regulators of Arabidopsis root development. Nature 449, 1053–1057. 10.1038/nature06206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallusci P., Dai Z., Génard M., Gauffretau A., Leblanc-Fournier N., Richard-Molard C., et al. (2017). Epigenetics for plant improvement: current knowledge and modeling avenues. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 610–623. 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.-E., Hu Z., Yu X., Li A., Li F., Wang Y., et al. (2018). A histone deacetylase gene, SlHDA3, acts as a negative regulator of fruit ripening and carotenoid accumulation. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 125–135. 10.1007/s00299-017-2211-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S.-K., Sang Y., Rodrigues A., BIOL425 F2010. Wu M.-F., Rodriguez P. L., et al. (2012). The SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling ATPase BRAHMA represses abscisic acid responses in the absence of the stress stimulus in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 24, 4892–4906. 10.1105/tpc.112.105114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébrard C., Peterson D. G., Willems G., Delaunay A., Jesson B., Lefèbvre M., et al. (2016). Epigenomics and bolting tolerance in sugar beet genotypes. J. Exp. Botany 67, 207–225. 10.1093/jxb/erv449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth J., Dean C. (2015). Flowering Locus C's lessons: conserved chromatin switches underpinning developmental timing and adaptation. Plant Physiol. 168, 1237–1245. 10.1104/pp.15.00496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M., Iwase A., Rymen B., Harashima H., Shibata M., Ohnuma M., et al. (2015). PRC2 represses dedifferentiation of mature somatic cells in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 1:15089. 10.1038/nplants.2015.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz M., Conrath U., Peterhänsel C. (2011). Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. EMBO Rep. 12, 50–55. 10.1038/embor.2010.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H., Shibahara K., Taoka K., Iwabuchi M., Stillman B., Araki T. (2001). FASCIATA genes for chromatin assembly factor-1 in Arabidopsis maintain the cellular organization of apical meristems. Cell 104, 131–142. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00197-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C. S. (2005). WUSCHEL is a primary target for transcriptional regulation by SPLAYED in dynamic control of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 19, 992–1003. 10.1101/gad.1276305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowiec J., Queitsch C., Kliebenstein D. J. (2016). Molecular mechanisms governing differential robustness of development and environmental responses in plants. Ann. Botany 117, 795–809. 10.1093/aob/mcv151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon-Placette C., Le Gac A.-L., Chauveau D., Segura V., Delaunay A., Lesage-Descauses M.-C., et al. (2018). Changes in the epigenome and transcriptome of the poplar shoot apical meristem in response to water availability affect preferentially hormone pathways. J. Exp. Botany 69, 537–551. 10.1093/jxb/erx409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafos M., Kroll P., Hohenstatt M. L., Thorpe F. L., Clarenz O., Schubert D. (2011). Dynamic regulation of H3K27 trimethylation during Arabidopsis differentiation. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002040. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lämke J., Bäurle I. (2017). Epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms in environmental stress adaptation and stress memory in plants. Genome Biol. 18:124. 10.1186/s13059-017-1263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latzel V., Zhang Y., Karlsson Moritz K., Fischer M., Bossdorf O. (2012). Epigenetic variation in plant responses to defence hormones. Ann. Botany 110, 1423–1428. 10.1093/aob/mcs088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura B., Silvia P., Francesca F., Benedetta S., Carla C. (2018). Epigenetic control of defense genes following MeJA-induced priming in rice (O. sativa). J. Plant Physiol. 228, 166–177. 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gac A.-L., Lafon-Placette C., Chauveau D., Segura V., Delaunay A., Fichot R., et al. (2018). Winter-dormant shoot apical meristem in poplar trees shows environmental epigenetic memory. J. Exp. Botany 69, 4821–4837. 10.1093/jxb/ery271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.-F., Lu J., Yu J.-W., Zhang C.-Q., He J.-X., Liu Q.-Q. (2018). The brassinosteroid-regulated transcription factors BZR1/BES1 function as a coordinator in multisignal-regulated plant growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1861, 561–571. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Liu H., Cheng Z. J., Su Y. H., Han H. N., Zhang Y., et al. (2011). DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis by modulating WUSCHEL expression and auxin signaling. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002243. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Xin Y., Xu L., Cai Z., Xue Y., Liu Y., et al. (2018). Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE 1 binds chromatin to promote gene transcription in response to hormones and stresses. Dev. Cell 44, 348–361.e7. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang H., Dong Y. X., Hao Y. J., Zhang X. S. (2018). DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE1 -mediated shoot regeneration is regulated by cytokinin-induced cell cycle in Arabidopsis. N. Phytol. 217, 219–232. 10.1111/nph.14814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. C., Lämke J., Lin S., Hung M.-J., Liu K.-M., Charng Y., Bäurle I. (2018). Distinct heat shock factors and chromatin modifications mediate the organ-autonomous transcriptional memory of heat stress. Plant J. 95, 401–413. 10.1111/tpj.13958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wei X., Sheng Z., Jiao G., Tang S., Luo J., et al. (2016). Polycomb protein OsFIE2 affects plant height and grain yield in rice. PLoS ONE 11:e0164748. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdi S., Derkacheva M., Ramström M., Kralemann L., Bergquist J., Hennig L. (2016). The WD40 domain protein MSI1 functions in a HDAC complex to fine-tune ABA signaling. Plant Cell 28, 42–54. 10.1105/tpc.15.00763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morao A. K., Bouyer D., Roudier F. (2016). Emerging concepts in chromatin-level regulation of plant cell differentiation: timing, counting, sensing and maintaining. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 34, 27–34. 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozgová I., Mu-oz-Viana R., Hennig L. (2017). PRC2 represses hormone-induced somatic embryogenesis in vegetative tissue of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006562. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J., Cheng J.-C., Sung Z.R., Somerville C. (1997). Cellular differentiation regulated by gibberellin in the Arabidopsis thaliana pickle mutant. Sciences 277, 91–94. 10.1126/science.277.5322.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J., Kaufmann S., Henderson J., Somerville C. (1999). PICKLE is a CHD3 chromatin-remodeling factor that regulates the transition from embryonic to vegetative development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13839–13844. 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S., Park S., van Nocker S. (2008). Genic and global functions for Paf1C in chromatin modification and gene expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000077. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojolo S. P., Cao S., Priyadarshani S. V. G. N., Li W., Yan M., Aslam M., et al. (2018). Regulation of plant growth and development: a review from a chromatin remodeling perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1232. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oles V., Panchenko A., Smertenko A. (2017). Modeling hormonal control of cambium proliferation. PLoS ONE 12:e0171927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Oh D.-H., Dassanayake M., Nguyen K. T., Ogas J., Choi G., et al. (2017). Gibberellin signaling requires chromatin remodeler PICKLE to Promote vegetative growth and phase transitions. Plant Physiol. 173, 1463–1474. 10.1104/pp.16.01471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic M., Radotic K. (2017). Animal and Plant Stem Cells, Vol. 234 Cham: Springer International Publishing XVII. [Google Scholar]

- Peirats-Llobet M., Han S.-K., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Jeong C. W., Rodriguez L., Belda-Palazon B., et al. (2016). A direct link between abscisic acid sensing and the chromatin-remodeling ATPase BRAHMA via core ABA signaling pathway components. Mol. Plant 9, 136–147. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella G., Lopez-Vernaza M. A., Carr C., Sani E., Gossele V., Verduyn C., et al. (2013). Histone deacetylase complex1 expression level titrates plant growth and abscisic acid sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 3491–3505. 10.1105/tpc.113.114835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi L., Aichinger E., van der Graaff E., Llavata-Peris C. I., Weijers D., Hennig L., et al. (2015). Organizer-derived WOX5 signal maintains root columella stem cells through chromatin-mediated repression of CDF4 expression. Dev. Cell 33, 576–588. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnowska E., Gratkowska D. M., Sacharowski S. P., Cwiek P., Tohge T., Fernie A. R., et al. (2016). The role of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes in hormone crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 594–608. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. (2007). Stem-cell niches: nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 345–354. 10.1038/nrm2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorin C., Bussell J. D., Camus I., Ljung K., Kowalczyk M., Geiss G., et al. (2005). Auxin and light control of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis require ARGONAUTE1. Plant Cell 17, 1343–1359. 10.1105/tpc.105.031625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sow M. D., Allona I., Ambroise C., Conde D., Fichot R., Gribkova S., et al. (2018b). Epigenetics in forest trees, in Advances in Botanical Research. Plant Epigenetics Coming of Age for Breeding Applications, Vol. 88 éds Gallusci P., Bucher E., Mirouze M. 387–453. Academic Press, Elsevier; 10.1016/bs.abr.2018.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sow M. D., Segura V., Chamaillard S., Jorge V., Delaunay A., Lafon-Placette C., et al. (2018a). Narrow-sense heritability and PST estimates of DNA methylation in three Populus nigra L. populations under contrasting water availability. Tree Genet. Genomes 14:78 10.1007/s11295-018-1293-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Springer N. M., Schmitz R. J. (2017). Exploiting induced and natural epigenetic variation for crop improvement. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 563–575. 10.1038/nrg.2017.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Kikuchi A., Kamada H. (2008). The Arabidopsis Histone Deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 contribute to the repression of embryonic properties after germination. Plant Physiol. 146, 149–161. 10.1104/pp.107.111674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M. R., Laux T. (2007). Connecting the paths in plant stem cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 403–410. 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeel A., Ali I., Khan A. R., Wu M., Upreti S., Liu D., et al. (2018). Involvement of histone acetylation and deacetylation in regulating auxin responses and associated phenotypic changes in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 51–59. 10.1007/s00299-017-2205-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Ci D., Li T., Li P., Song Y., Chen J., et al. (2016). The role of DNA methylation in xylogenesis in different tissues of poplar. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1003. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. M., Chong G. L., Verslues P. E. (2017). Epigenetics and RNA processing: connections to drought, salt, and ABA?, in Plant Stress Tolerance: Methods and Protocols, ed Sunkar R. (New York, NY: Springer New York; ), 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Jin R., Wagner D. (2017). Developmental transitions: integrating environmental cues with hormonal signaling in the chromatin landscape in plants. Genome Biol. 18:88. 10.1186/s13059-017-1228-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Shen W.-H. (2008). Polycomb silencing of KNOX genes confines shoot stem cell niches in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 18, 1966–1971. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R. K., Girke T., Pasala S., Xie M., Reddy G. V. (2009). Gene expression map of the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem stem cell niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4941–4946. 10.1073/pnas.0900843106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev I. A., Asante D. K. A., Fossdal C. G., Junttila O., Johnsen Ø. (2011). Differential gene expression related to an epigenetic memory affecting climatic adaptation in Norway spruce. Plant Sci. 180, 132–139. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev I. A., Carneros E., Lee Y., Olsen J. E., Fossdal C. G. (2016). Transcriptional profiling of epigenetic regulators in somatic embryos during temperature induced formation of an epigenetic memory in Norway spruce. Planta 243, 1237–1249. 10.1007/s00425-016-2484-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamuro C., Zhu J.-K., Yang Z. (2016). Epigenetic modifications and plant hormone action. Mol. Plant 9, 57–70. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Li C., Zhao L., Gao S., Lu J., Zhao M., et al. (2015). The Arabidopsis SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling ATPase BRAHMA targets directly to PINs and is required for root stem cell niche maintenance. Plant Cell 27, 1670–1680. 10.1105/tpc.15.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Li L., Li L., Guo M., Chory J., Yin Y. (2008). Modulation of brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression by jumonji domain-containing proteins ELF6 and REF6 in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7618–7623. 10.1073/pnas.0802254105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Hou H., Zhang H., Yue M., Hu Y., Li L. (2018). Histone acetylation is involved in GA-mediated 45S rDNA decondensation in maize aleurone layers. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 115–123. 10.1007/s00299-017-2207-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J., Niu Q.-W., Frugis G., Chua N.-H. (2002). The WUSCHEL gene promotes vegetative-to-embryonic transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 30, 349–359. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]