Abstract

Background

Opioid addiction is one of the most common substance-related disorders worldwide, and morbidity and mortality due to opioid addiction place a heavy burden on society. Knowing the size of the population that is addicted to opioids is a prerequisite for the development and implementation of appropriate health-policy measures.

Methods

Our estimate for Germany for 2016 is based on an enumeration of opioid-addicted persons who were entered in a registry of persons receiving substitution therapy, an enumeration of persons receiving outpatient and inpatient care for addiction without substitution therapy, an extrapolation to all addiction care facilities, and an estimation of the number of opioid-addicted persons who were not accounted for either in the substitution registry or in addiction care.

Results

The overall estimate of the number of opioid-addicted persons in Germany in 2016 was 166 294 persons (lower and upper bounds: 164 794 and 167 794), including 123 988 men (122 968 to 125 007) and 42 307 women (41 826 to 42 787). The estimates for each German federal state per 1000 inhabitants ranged from 0.1 in Brandenburg to 3.0 in North Rhine-Westphalia and 5.5 in Bremen. The average value across Germany was 3.1 per 1000 inhabitants.

Conclusion

Comparisons with earlier estimates suggest that the number of persons addicted to opioids in Germany has hardly changed over the past 20 years. Despite methodological limitations, this estimate can be considered highly valid. Nearly all persons who are addicted to opioids are in contact with the addiction care system.

Opioid addiction is one of the most common substance-related disorders worldwide. It is responsible for the majority of the morbidity and mortality caused by drugs in the population (1). Opioids include both synthetic (e.g. heroin, methadone, buprenorphine, fentanyl) and plant-derived substances (opiates, e.g. codeine and morphine). Opioids carry major risks of physical and pharmacological dependency (2). Intravenous use, in particular, is associated with a non-negligible risk of communicable diseases (3) or death due to overdose or the long-term consequences of use (4). Finally, there is an increased risk of criminal behavior, specifically drug-related crime (5).

Knowing how many individuals are addicted to opioids is important for setting health policy (6). In the first instance, calculations in Germany concern addiction caused by taking illegal opioid-containing substances. A preliminary national estimate for Germany as a whole in 1989, based on treatment data, gave a figure of 60 000 to 80 000 individuals who were problem users of opiates, cocaine, stimulants, or hallucinogenic drugs (7). A German expert group estimated the number of heroin users in western and eastern Germany in 1995 at 127 000 to 152 000 (8); for the same year, the number of intravenous drug users in western Germany and Berlin was estimated at a mean of 150 000 (97 000 to 204 000) on the basis of a survey among general practitioners (9).

As part of estimating the number of individuals with problematic drug use in European Union countries, figures of 127 000 to 190 000 opiate users in Germany for the year 2000 were found using various methods. This calculation was based on treatment, police, and mortality data (10). Using these approaches, comparative estimates for 1990, 1995, and 2000 indicated a moderate increase in the number of opiate users (11).

The aim of this study was to estimate the number of individuals addicted to opioids in Germany and its individual federal states for the calendar year 2016.

Method

This estimate is based on substitution treatment registry data, data from inpatient and outpatient addiction care statistics, and counts in 5 low-threshold addiction care facilities. We assume that all data was recorded inasmuch as all individuals addicted to opioids come into some form of contact with the addiction care system. We draw a distinction between individuals who are documented in the addiction care system and those who come into contact with the system but only receive care that is not documented.

Although there are no diagnoses for individuals with no case documentation, it can nevertheless be assumed from care they have received, e.g. needle exchange, that they are addicted to opioids.

Cases are documented when an individual addicted to opioids is prescribed an opioid substitute by his/her treating physician. The coded patient data reported by the doctor to Germany’s Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM, Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte) is added to the substitution treatment registry there in encrypted form (12). Double entries resulting from the same code being used for 2 individuals were ruled out by consulting the treating physicians.

Individuals addicted to opioids are also documented if they receive treatment at inpatient or outpatient addiction care facilities which is recorded in Germany’s Addiction Care Statistical Service, DSHS (Deutsche Suchthilfestatistik) (13). The DSHS data was used to estimate how many individuals were addicted to opioids and did not undergo substitution treatment in addiction care facilities. Cases with “opioid addiction” as primary or secondary diagnosis in various types of addiction care facilities were used. The included facilities are of the following types, as defined in DSHS:

Low-threshold facilities with case documentation, such as emergency shelters or drug consumption rooms (type 2)

Outpatient counseling and/or treatment facilities outpatient facilities within institutions, and specialist walk-in clinics (types 3 and 4)

Semiresidential rehabilitation facilities (type 8)

Residential rehabilitation facilities (type 9)

Transition facilities (type 10)

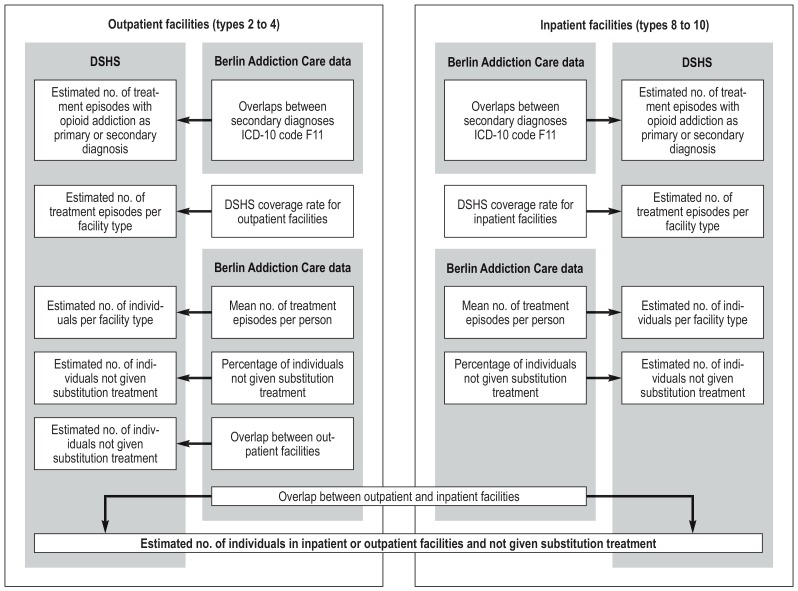

Unlike the substitution treatment registry, the DSHS records treatment episodes rather than individuals and reports only aggregate data, so double entries of individuals cannot be checked. Individuals may be counted twice if they are recorded at both inpatient and outpatient facilities. Correction factors were calculated using Berlin’s Addiction Care Statistical Service (Suchthilfe Berlin) data (15) and used to convert DSHS data on treatment episodes to individual-related data and to estimate the overlap with individuals addicted to opioids and undergoing substitution treatment. Because the DSHS does not cover all addiction care facilities, data was extrapolated to the total number of addiction care facilities (Figure; see eMethods for a detailed description).

Figure.

Method followed for estimating the number of individuals not given substitution treatment for opioid addiction in outpatient counseling and/or treatment facilities with case documentation and inpatient addiction treatment facilities, based on Germany’s Addiction Care Statistical Service (DSHS) and Berlin’s Addiction Care Statistical Service

Individuals addicted to opioids are not recorded in the DSHS if they attend a low-threshold facility with no case documentation and use its services, e.g. when addiction care is provided together with social work. In order to estimate the size of this group as a proportion of all individuals addicted to opioids, clients at 5 selected facilities in Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich, and Nuremberg were routinely surveyed, for example during needle exchange, at contact points, or at mobile addiction care services. The use of addiction care facilities was surveyed between July and September 2017 as part of regular contact. Addiction professionals recorded clients’ sex and their opioid consumption in the last 12 months and asked which addiction care facilities, by DSHS types, they had attended in the same period. Facilities ruled out double entries using, for example, personal acquaintance, lists of pseudonyms, or statement of characteristics. Clients with insufficient knowledge of German were largely handled by professionals with knowledge of the relevant language (e.g. Farsi, Russian, Turkish). Logistic regression was used to estimate 95% confidence intervals for the percentages of all individuals who used opioids and who used only services with no case documentation, for the sample as a whole and by sex. The facility type was used as control variable.

To estimate the number of individuals addicted to opioids, the estimated percentage of individuals not undergoing substitution treatment and with no case documentation (NST) was added to the number of individuals not undergoing substitution treatment estimated on the basis of the DSHS data (AC). Upper and lower limits were set using the 95% confidence intervals of the estimate of the proportion of individuals with no case documentation (NCD). The total estimate (upper and lower limits) includes the number of individuals undergoing substitution treatment (St + NST). These steps were taken for men and for women.

The number of individuals addicted to opioids for each federal state in Germany was estimated using the number of patients reported as undergoing substitution treatment on the sample day July 1, 2016 in each federal state (12). These figures were used to calculate a percentage for each federal state on the basis of the reported total number.

Results

Substitution treatment

A total of 123 387 encrypted codes were recorded in the database of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) between 1 July, 2016 and 30 June, 2017. After codes entered twice or multiple times had been removed 93 939 different codes remained. A total of 0.99% of the reports were identical by chance and should not have been removed from the total number of codes, so 442 cases (0.99% of 44 887) were added. This led to a figure of 94 381 for the number of patients undergoing substitution treatment in 2016 according to the substitution treatment registry.

Inpatient or outpatient addiction care

The number of individuals addicted to opioids and not undergoing substitution treatment was obtained from the DSHS data in line with the following characteristics:

Sex

Primary diagnoses (ICD-10 codes F10 to F19, F50, F63), including secondary diagnoses F11 (disorders due to use of opioids)

Type of facility

Adjustment for possible multiple entries (secondary diagnoses F11, multiple treatments within and between facilities)

The estimated figure was 66 220 individuals (50 953 men and 15 267 women) addicted to opioids and not undergoing substitution treatment.

Low-threshold facilities with no case documentation

A total of 884 individuals addicted to opioids were recorded in routine documentation at the 5 locations. It was estimated that 9.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.6 to 11.6%) of men and 5.2% (2.1 to 8.4%) of women used only low-threshold facilities or other addiction care with no case documentation.

Estimate for Germany as a whole

The estimated total figure is 166 294 (range: 164 794 to 167 794) individuals addicted to opioids, of whom 123 988 (range: 122 968 to 125 007) are men and 42 307 (range: 41 826 to 42 787) are women (table 1). As the recorded population of Germany aged between 15 and 64 years in 2016 was 53 963 400 (17), this equates to a rate of 3.05 to 3.11 per thousand inhabitants.

Table 1. Estimated numbers of individuals addicted to opioids by status (substitution treatment, no substitution treatment, and no substitution treatment or case documentation).

| Status | Source | Women | Men | Total | |||

| Not undergoing substitution treatment, in addiction care (AC) | DSHS | 15 267 | 50 953 | 66 220 | |||

| Percentage of individuals not undergoing substitution treatment and with no case documentation (95% CI) (NCD) | Count | 2.1% | 8.4% | 7.6% | 11.6% | 6.3% | 10.9% |

| Not undergoing substitution treatment (NST) (AC + AC × NCD) |

15 588 | 16 549 | 54 825 | 56 864 | 70 413 | 73 413 | |

| Undergoing substitution treatment (ST) | Substitution treatment registry | 26 238 *1 | 68 143 *1 | 94 381 | |||

| Total (ST + NST) | 41 826 | 42 787 | 122 968 | 125 007 | 164 794 | 167 794 | |

| 42 307 *2 | 123 988 *2 | 166 294 *2 | |||||

*172.2% men, 27.8% women (ECHO study [14]) of 94 381; *2Mean of upper and lower limits of total (ST + NST); DSHS: Deutsche Suchthilfestatistik (Germany’s Addiction Care Statistical Service); 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Estimate for federal states

Table 2 shows the estimated numbers of individuals addicted to opioids for individual federal states, based on the registered numbers of individuals undergoing substitution treatment in those states. Estimated rates for federal states range from 0.1 per thousand inhabitants in Brandenburg to 5.5 per thousand in Bremen (see eTable for details).

Table 2. Estimated total number of individuals addicted to opioids, population in 2016, and rate of opioid addiction per 1000 inhabitants by federal state.

| Federal state | Estimate | Population 2016 | Rate per 1000 |

| Baden-Württemberg | 21 832 | 10 951 893 | 1.9 |

| Bavaria | 16 713 | 12 930 751 | 1.3 |

| Berlin | 10 943 | 3 574 830 | 3.1 |

| Brandenburg | 248 | 2 494 648 | 0.1 |

| Bremen | 3745 | 678 753 | 5.5 |

| Hamburg | 8847 | 1 810 438 | 4.9 |

| Hesse | 16 042 | 6 213 088 | 2.6 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 538 | 1 610 674 | 0.3 |

| Lower Saxony | 16 794 | 7 945 685 | 2.1 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 53 851 | 17 890 100 | 3.0 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 4672 | 4 066 053 | 1.1 |

| Saarland | 1480 | 996 651 | 1.5 |

| Saxony | 1342 | 4 081 783 | 0.3 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 1467 | 2 236 252 | 0.7 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 6961 | 2 881 926 | 2.4 |

| Thuringia | 819 | 2 158 128 | 0.4 |

*Extrapolation of figures of Germany’s Federal Statistical Office (Destatis, Statistisches Bundesamt), sampled on December 31, 2016

eTable. Estimated numbers of individuals addicted to opioids by status (substitution treatment, no substitution treatment, and no substitution treatment or case documentation) by federal state.

| Men | Women | Total | ||||||||||||

| Federal state | n*1 | % | Substitution treatment | AC*2 | NCD*3 | AC*2 | NCD*3 | Estimate | Inhabitants in 2016*5 | Rate per 1000 | ||||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | Mean*4 | ||||||||

| Baden-Württemberg | 10 313 | 13.1 | 12 391 | 6689 | 508 | 776 | 2004 | 42 | 168 | 21 635 | 22 029 | 21 832 | 10 951 893 | 1.9 |

| Bavaria | 7895 | 10.1 | 9486 | 5121 | 389 | 594 | 1534 | 32 | 129 | 16 563 | 16 864 | 16 713 | 12 930 751 | 1.3 |

| Berlin | 5169 | 6.6 | 6211 | 3353 | 255 | 389 | 1005 | 21 | 84 | 10 844 | 11 041 | 10 943 | 3 574 830 | 3.1 |

| Brandenburg | 117 | 0.1 | 141 | 76 | 6 | 9 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 245 | 250 | 248 | 2 494 648 | 0.1 |

| Bremen | 1769 | 2.3 | 2125 | 1147 | 87 | 133 | 344 | 7 | 29 | 3711 | 3779 | 3745 | 678 753 | 5.5 |

| Hamburg | 4179 | 5.3 | 5 21 | 2711 | 206 | 314 | 812 | 17 | 68 | 8767 | 8927 | 8847 | 1 810 438 | 4.9 |

| Hesse | 7578 | 9.6 | 9105 | 4915 | 374 | 570 | 1473 | 31 | 124 | 15 898 | 16 187 | 16 042 | 6 213 088 | 2.6 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 254 | 0.3 | 305 | 165 | 13 | 19 | 49 | 1 | 4 | 533 | 543 | 538 | 1 610 674 | 0.3 |

| Lower Saxony | 7933 | 10.1 | 9531 | 5146 | 391 | 597 | 1542 | 32 | 130 | 16 642 | 16 945 | 16 794 | 7 945 685 | 2.1 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 25 438 | 32.4 | 30 564 | 16 500 | 1254 | 1914 | 4944 | 104 | 415 | 53 366 | 54 337 | 53 851 | 17 890 100 | 3.0 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 2207 | 2.8 | 2652 | 1432 | 109 | 166 | 429 | 9 | 36 | 4630 | 4714 | 4672 | 4 066 053 | 1.1 |

| Saarland | 699 | 0.9 | 840 | 453 | 34 | 53 | 136 | 3 | 11 | 1466 | 1493 | 1480 | 996 651 | 1.5 |

| Saxony | 634 | 0.8 | 762 | 411 | 31 | 48 | 123 | 3 | 10 | 1330 | 1354 | 1342 | 4 081 783 | 0.3 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 693 | 0.9 | 833 | 450 | 34 | 52 | 135 | 3 | 11 | 1454 | 1480 | 1467 | 2 236 252 | 0.7 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 3288 | 4.2 | 3951 | 2133 | 162 | 247 | 639 | 13 | 54 | 6898 | 7023 | 6961 | 2 881 926 | 2.4 |

| Thuringia | 387 | 0.5 | 465 | 251 | 19 | 29 | 75 | 2 | 6 | 812 | 827 | 819 | 2 158 128 | 0.4 |

*1Substitution treatment registry, sampled on July 1, 2016; *2AT: Individuals not undergoing substitution treatment and in addiction care; *3NCD: Individuals not undergoing substitution treatment and with no case documentation; *4Mean of upper and lower limits; *5Extrapolation of figures of Germany’s Federal Statistical Office (Destatis, Statistisches Bundesamt), sampled on December 31, 2016

Discussion

The estimated number of individuals addicted to opioids in Germany in 2016 is based on the following:

Documentation of all individuals undergoing substitution treatment reported to the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM)

A count of clients who are addicted to opioids, reported as receiving inpatient or outpatient addiction care, and not undergoing substitution treatment according to DSHS data

An estimate of the number of individuals who did not use any of the addiction care facilities stated in the 2 points above

The findings for these 3 points give a total estimate of 166 294 (range: 164 794 to 167 794) individuals addicted to opioids in Germany, of whom 123 988 (range: 122 968 to 125 007) are men and 42 307 (range: 41 826 to 42 787) are women.

There are no current figures for Germany or its federal states except for this estimate and one study in Berlin (18). This estimate is of a similar mean value to earlier estimates from the year 1995—97 000 to 204 000 intravenous drug users in western Germany and Berlin (9)—and from the year 2000—127 000 to 190 000 opiate users in Germany as a whole (10). Although the 1995 estimate was for western Germany and Berlin and concerned intravenous drug users, after Germany’s reunification opioid consumption was almost zero in the new federal states in the 1990s and intravenous use was the most popular route of administration in Western Europe.

Comparisons with earlier estimates of the numbers of individuals addicted to opioids in Berlin are limited by the fact that this evaluation uses only national data, not regional data. Our figures—10 844 to 11 041 individuals addicted to opioids in Berlin—are somewhat lower than the figures for 2010—11 300 to 16 700 individuals addicted to opioids (18). Provided that this is not an overestimate and that the number of people addicted to opioids in Berlin did not change substantially between 2010 and 2016, it cannot be assumed that the number of individuals addicted to opioids who did not undergo substitution treatment and were not registered is proportional to the number of patients undergoing substitution treatment recorded in Germany’s federal states. If it were, the number of individuals addicted to opioids who did not undergo substitution treatment and were not recorded would be higher than estimated here in federal city states and those federal states with large cities and a large drug scene. In contrast, the estimates for other federal states would be slightly overestimated. However, the regional distribution of individuals addicted to opioids who do not undergo substitution treatment and are not registered may also be subject to effects other than those assumed here. Our estimates for federal states are therefore merely approximate.

In our study, the number of individuals addicted to opioids currently undergoing substitution treatment was 56.2 to 57.3% of the total estimate. The findings of the DRUCK study (“DRUCK” = Drogen und Chronische Infektionskrankheiten—“Drugs and chronic infectious diseases”) (19), based on a sample of intravenous drug users addicted to opioids, indicate that 57 to 89% of clients in different cities have ever undergone opioid substitution treatment and 31 to 66% are currently undergoing substitution treatment. Addiction care data for Hamburg (Basisdokumentation BADO) indicates that in 2016 75% of clients diagnosed with opioid addiction were undergoing substitution treatment (20).

Limitations

Our estimate has a number of limitations. The validity of the data in the substitution treatment registry depends on the completeness and quality of physicians’ reports. There are also the lack of age-specific data in the substitution treatment registry, the conversion of DSHS data on treatment episodes to individual-based data, and the use of Berlin´s Addiction Care Statistical Service (Suchthilfe Berlin) data to calculate correction factors and the associated assumption of representativeness. Other than Berlin´s Addiction Care Statistical Service data, relevant individual-related data is available only for Hamburg, Hesse, and Schleswig-Holstein (20), and this does not allow a representative estimate to be made for Germany either. Finally, it must be pointed out that individuals addicted to opioids who were incarcerated, in facilities for integration into society, or in acute care could not be included in the estimate, even though it can be assumed that there is great overlap with the data sources used. Our estimate should therefore be treated as conservative.

This estimate assumes that almost everyone addicted to opioids is in some kind of contact with the addiction care system. Studies in the open drug scene indicate that a total of 93 to 99% of those surveyed (2010: 99%; 2012: 98%; 2014: 96%; 2016: 93%) have used the addiction care system at least once in the last 3 months, mostly in the area of harm reduction, such as needle exchange or drug consumption rooms (21). However, the existence of a population of opioid users who could potentially be diagnosed with addiction and who cannot be counted among harm reduction service users cannot be ruled out. These might include, for example, individuals who are integrated into society, who have the financial means to procure opioids, and who use opioids with no impact on society or damage to their health.

Summary

Epidemiological data indicates that first demand for addiction counseling and/or treatment, the number of first-time users, and the number of drug law violations due to heroin and other opioid use have been decreasing for years. There is also evidence that the range of drugs available has expanded substantially in the last 20 years and that consumption patterns have diversified.

The overall scale of heroin and other opioid use has fallen in recent years, and opioid use seems to be less attractive to young people than stimulant use, for example (22). The increasingly older clients who attend advice and treatment facilities for opioid use and the substantial increase in the mean age of those dying of opioid overdoses in the last 20 years also point in this direction. However, comparison of our estimate with earlier estimates suggests that the number of individuals addicted to opioids in Germany has barely changed in the last 20 years. This can be explained by stagnation of the prevalence of opioid addiction and a decline in its incidence.

Although substitution treatment makes a substantial contribution to ensuring patients’ survival (23), only some 4% of patients per year successfully complete treatment (24– 26). At the same time, there is evidence in the literature of a decline in new cases of opioid-related disorders in Europe (27– 29). Consequently, prevalence is falling only in the long term, as substitution treatment has been rolled out comprehensively, leading to better survival and the ageing of the population of users as a whole. However, the dramatic increase in opioid-related mortality observed in the USA in the last two decades in the context of liberal prescription of opioid-containing analgesics to patients with chronic, non-cancer-related pain (30) suggests that more attention must be paid to preventing possible iatrogenic opioid addiction disorders using appropriate countermeasures.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS

This section provides more detail on the calculation of the steps shown in the Figure. We have used no mathematical formulae.

Aim: Data from Germany’s Addiction Care Statistical Service, DSHS (Deutsche Suchthilfestatistik), is available only in aggregate form, based on treatment episodes. Individual-based data from Berlin’s Addiction Care Statistical Service (Suchthilfe Berlin) was used to calculate correction factors that make it possible to convert the DSHS data on treatment episodes step by step to individual-related data and to extrapolate it to the target group of individuals not given substitution treatment in each individual type of addiction care facility. Because the number of individuals addicted to opioids was to be estimated, only individuals or treatment episodes with a main or secondary diagnosis of opioid dependency (ICD/10 code F11) were included.

Corrections were performed separately for each facility type (type 2, types 3 to 4, types 8 to 10), for men and for women. Next, overlaps between inpatient and outpatient facilities were taken into account.

Overlaps between secondary diagnoses F11

Problem (DSHS)

Both primary diagnosis and secondary diagnoses were recorded for all individuals. Secondary diagnoses F11 fell into four categories:

One person was allocated a primary diagnosis but not only one of the four secondary diagnoses. For secondary diagnoses, one person may therefore have been included multiple times. This means the total number of treatment episodes within one primary diagnosis of the four F11 secondary diagnoses was higher, so the figures had to be corrected for secondary diagnoses F11.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For each primary diagnosis (F10 to F19, F50, F63, no primary diagnosis), the arithmetic mean of the number of treatment episodes for secondary diagnoses F11 was calculated as a correction factor.

Correction (DSHS)

The number of treatments for main or secondary diagnosis F11 was adjusted in the DSHS data using the above-mentioned correction factor, with stratification by primary diagnosis. For example, if a total of 96 treatment episodes had been recorded for primary diagnosis F10 with secondary diagnosis F11 but there were 108 treatment episodes altogether for the four secondary diagnoses F11, the correction factor 96/108 = 0.89 was calculated. This was then applied to the relevant DSHS figures and multiplied by the total number of treatment episodes for the four secondary diagnoses F11. This meant that the number of treatment episodes per primary diagnosis could be estimated without the influence of secondary diagnoses F11.

Indication

Individuals may also have been treated for different primary diagnoses at different facilities or during different treatment episodes. This was not taken into account in the corrections, as the inclusion of all possible combinations of multiple primary diagnoses for small patient numbers might have led to major bias. In the Berlin Addiction Care Statistical Service data, for example, multiple primary diagnoses (including “no primary diagnosis”) were more frequent in outpatient facilities: for one individual there were a total of 4 different primary diagnoses in the treatment year, for 50 individuals there were 3 primary diagnoses, and for 1232 individuals there were 2 primary diagnoses. Almost all possible diagnoses were present in different combinations (a precise list of all combinations cannot be included here for reasons of space). Essentially, 31 primary diagnoses were recorded using KDS 2.0 (“KDS” stands for Kerndatensatz, the German for “main dataset” and is the DSHS recording system for 2016). The total number of combinations of 2 and 3 primary diagnoses is more than 30 000 (312 + 313 = 30 752) even though patient numbers are small in each case.

DSHS coverage rate

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data does not cover all addiction care facilities in Germany, so it records only a certain proportion of the total number of treatment episodes. This means the number of treatment episodes recorded in the DSHS data has to be extrapolated to the total number of treatment episodes in Germany.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For each line in the table the coverage rate is calculated using the Süß und Pfeiffer-Gerschel method (16) for both inpatient and outpatient facilities. In 2016 the coverage rate was 73.38% for outpatient facilities and 61.61% for inpatient facilities. The calculations are based on the data of the central Registry of Addiction Care Facilities maintained by the German Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (DBDD, Deutsche Beobachtungsstelle für Drogen und Drogensucht) and funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Health.

Correction (DSHS)

The number of treatment episodes stated was extrapolated to the total number of treatment episodes in Germany (100%) using each coverage rate (73.88% for outpatient facilities, 61.61% for inpatient facilities).

Mean number of treatment episodes per person

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data may include individuals multiple times for multiple treatment episodes. This increases the total number of all treatment episodes within one primary diagnosis. This means the number of treatment episodes per person needs to be corrected.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

The mean number of treatment episodes for all individuals was stratified by primary diagnosis. This figure was between 1.00 and 1.12 treatment episodes person.

Correction (DSHS)

Using this correction factor, the number of treatment episodes stratified by sex was converted to the number of individuals treated at each facility type.

Percentage of people not given substitution treatment

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data contains no explicit information on whether individuals were also undergoing substitution treatment during a treatment episode. This means the percentages of individuals who did or did not undergo substitution treatment needs to be estimated.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals with a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or with primary diagnosis F11, it was ascertained whether one or more substitution treatments (substance prescription) or psychosocial treatments concomitant with substitution treatment had been administered during the treatment year. This, in turn, provided information on the percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment. This percentage ranged from 69.1% to 100%.

Correction (DSHS)

The percentage of individuals not given substitution treatment was used to calculate the number of individuals not given substitution treatment as a percentage of the estimated total figure.

Overlaps between outpatient facilities

Problem (DSHS)

Individuals may have been counted multiple times for facilities of type 2 and types 3 to 4 if they attended facilities of different types. This means correction for multiple inclusions in different facilities must be performed.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment, who had a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or a primary diagnosis F11, and who attended type 3 or 4 facilities, it was ascertained whether treatment episodes had also been reported in type 2 facilities. This yields a percentage of individuals treated in type 2 facilities who were included multiple times. The percentage was 0% for most primary diagnoses but in individual cases was as high as 82% (F12) or 100% (F10).

Correction (DSHS)

The estimated percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment in type 2 facilities was therefore corrected to remove multiple counts due to treatment episodes in type 3 or 4 facilities.

Overlaps between inpatient and outpatient facilities

Problem (DSHS)

Individuals may have been documented multiple times due to treatment episodes in both inpatient and outpatient facilities. This means the data needs to be corrected to remove multiple counts in both inpatient and outpatient facilities.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment and with a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or primary diagnosis F11, the percentage of individuals who attended both outpatient facilities (types 2, 3, and 4) and inpatient facilities (types 8, 9, and 10) was calculated.

Correction (DSHS)

The percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment and who attended both inpatient and outpatient facilities was applied to the number of individuals in outpatient facilities and thus reduced the number of individuals in outpatient facilities. This percentage ranged from 0% to 100% (the latter included F13, F14, F19, and others).

Individuals addicted to opioids, not given substitution treatment, and receiving addiction care

In order to obtain the total number of individuals addicted to opioids, the estimated figures per primary diagnosis were added together, by sex and overall.

Heroin addiction

Methadone addiction

Buprenorphine addiction

Addiction to other opiate-containing drugs

Key Messages.

The approach used here allows for documentation of almost all individuals addicted to opioids in Germany on the basis of registry data.

The number of individuals addicted to opioids who are in contact with low-threshold facilities and are not recorded in the addiction care system can be estimated.

There is a high level of agreement between the total estimate for Germany presented here—166 294 individuals addicted to opioids—and earlier estimates.

There are substantially fewer individuals addicted to opioids in federal states in eastern Germany (with the exception of Berlin) than in western Germany.

The highest rates of opioid addiction are expected in federal city states: Bremen, Hamburg, and Berlin.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PD Dr. Verthein has received reimbursement of conference fees and travel costs and lecture fees from Mundipharma GmbH.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Funding

The study Estimation of the number of people with opioid addiction in Germany was funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Health (file no.: ZMVI1–2517DSM209).

Acknowledgment

Estimating the number of individuals who have attended low-threshold facilities would have been impossible without the help of addiction care facility staff. We would like to thank the following facilities and their employees for their support: Drob Inn St. Georg Advice and Treatment Center, Hamburg: Christine Tügel and the Drob Innmobile team; Fixpunkt – Verein für suchtbegleitende Hilfen e. V., Berlin: Astrid Leicht and the Kontaktstelle Druckausgleich team, mobile care at Kottbusser Tor and Stuttgarter Platz; JJ Jugendberatung und Jugendhilfe e.V., Frankfurt: Dr. Dieter Kunz, Wolfgang Barth, and the Drug Emergency Unit team; Mudra – Drogenhilfe e.V., Nuremberg: Bertram Wehner, Martin Kießling, Doris Salzmann, and the Contact Café and Streetwork team; Prop e. V. Association for Prevention, Youth Care, and Addiction Treatment, Munich: Regina Radke, Marco Stürmer, Andreas Czerny, Holger Meurer, and the Drug Emergency Unit L 43 (DND) team.

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1564–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schäfer M. Opioide. In: Tonner PH, Hein L, editors. Pharmakotherapie in der Anästhesie und Intensivmedizin. Berlin Springer: 2011. pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet. 2010;376:268–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60743-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendt M, Munk-Jorgensen P, Sher L, et al. Mortality among individuals with cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine, MDMA, and opioid use disorders: a nationwide follow-up study of Danish substance users in treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;114:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groenemeyer A. Drogen, Drogenkonsum und Drogenabhängigkeit. In: Albrecht G, Groenemeyer A, editors. Handbuch soziale Probleme. Wiesbaden Springer: 2012. pp. 433–493. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S, et al. Alcohol: no ordinary commodity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klingemann H, Goos C, Hartnoll R, Jablensky A, Rehm J. European summary on drug abuse. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bühringer G, Adelsberger F, Heinemann A, et al. Schätzverfahren und Schätzungen 1997 zum Umfang der Drogenproblematik in Deutschland. Sucht. 1997;43(Sonderheft 2):S79–S141. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirschner W, Kunert M. München Profil: 1997. Umfang und Struktur von iv. Drogenabhängigen in Deutschland (1995). Anonymes Monitoring in den Praxen niedergelassener Ärzte. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraus L, Augustin R, Frischer M, et al. Estimating prevalence of problem drug use at national level in countries of the European Union and Norway. Addiction. 2003;98:471–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Augustin R, Kraus L. Changes in prevalence of problem opiate use in Germany between 1990 and 2000. Eur Add Res. 2004;10:61–67. doi: 10.1159/000076115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bundesopiumstelle. Bericht zum Substitutionsregister (84.1 / 12.01.2017) www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Bundesopiumstelle/SubstitReg/Subst_Bericht2017.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2; 2017 (last accessed on 28 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thaller R, Specht S, Künzel J. Braun: Suchthilfe in Deutschland 2016. Jahresbericht der deutschen Suchthilfestatistik (DSHS). München: IFT Institut für Therapieforschung 2017. www.suchthilfestatistik.de/fileadmin/user_upload_dshs/Publikationen/Jahresberichte/DSHS_Jahresbericht_2016.pdf (last accessed on 28 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strada L, Schmidt CS, Rosenkranz M, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in a large national sample of patients receiving opioid substitution treatment in Germany: a cross-sectional study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14 doi: 10.1186/s13011-018-0187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Specht S, Dauber H, Künzel J, Braun B. IFT Institut für Therapieforschung. München: 2018. Suchthilfestatistik 2016 Jahresbericht zur aktuellen Situation der Suchthilfe in Berlin (in Vorbereitung) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Süss B, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T. Bestimmung der Erreichungsquote der Deutschen Suchthilfestatistik auf Basis des DBDD-Einrichtungsregisters. Sucht. 2011;57:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) Bevölkerungsstand. Bevölkerung nach Altersgruppen, Familienstand und Religionszugehörigkeit. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) 2016; www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/AltersgruppenFamilienstandZensus. html (last accessed on 28 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus L, Steppan M, Piontek D. Schätzung der Prävalenz substanzbezogener Störungen in Berlin: Opioide, Kokain und Stimulanzien München: IFT Institut für Therapieforschung 2015. www.ift.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Literatur/Berichte/Kraus_Steppan_Piontek_2015_CRC_Berlin.pdf(last accessed on 28 January 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert Koch-Institut (RKI) Robert Koch Institut. Berlin: 2016. Abschlussbericht der Studie „Drogen und chronische Infektionskrankheiten in Deutschland“ (DRUCK-Studie) DOI: 10.17886/rkipubl-2016-007.2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindemann C, Neumann-Runde E, Martens MS. Bado e. V. Hamburg: 2017. Suchthilfe in Hamburg Statusbericht 2016 der Hamburger Basisdatendokumentation in der ambulanten Suchthilfe und der Eingliederungshilfe. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werse B, Sarvari L, Egger D, Feilberg N. Centre for Drug Research. Frankfurt am Main: 2017. MoSyD - Die offene Drogenszene in Frankfurt am Main 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piontek D, Dammer E, Schulte L, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Bartsch G, Friedrich M. Deutsche Beobachtungsstelle für Drogen und Drogensucht DBDD. München: 2017. Bericht 2017 des nationalen REITOX-Knotenpunkts an die EBDD (Datenjahr 2016/2017) Deutschland, Workbook Drogen. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soyka M, Träder A, Klotsche J, et al. Mortalität in der langfristigen Substitution: Häufigkeit, Ursachen und Prädiktoren. Suchtmed. 2011;13:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittchen HU, Bühringer G, Rehm J, et al. Der Verlauf und Ausgang von Substitutionspatienten unter den aktuellen Bedingungen der deutschen Substitutionsversorgung nach 6 Jahren. Suchtmed. 2011;13:232–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verthein U, Götzke C, Strada L, et al. Completion of opioid substitution treatment - an observational prospective study. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2017;19:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zippel-Schulz B, Specka M, Cimander K, et al. Outcomes of patients in long-term opioid maintenance treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:1493–1503. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1188946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Angelis D, Hickman M, Yang S. Estimating long-term trends in the incidence and prevalence of opiate use/injecting drug use and the number of former users: Back-calculation methods and opiate overdose deaths. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:994–1004. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordt C, Stohler R. Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:1830–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Niubo A, Fortiana J, Barrio G, et al. Problematic heroin use incidence trends in Spain. Addiction. 2009;104:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhalla, IA, Persaud N, Juurlink, DN. Facing up to the prescription opioid crisis. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5142. d5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

This section provides more detail on the calculation of the steps shown in the Figure. We have used no mathematical formulae.

Aim: Data from Germany’s Addiction Care Statistical Service, DSHS (Deutsche Suchthilfestatistik), is available only in aggregate form, based on treatment episodes. Individual-based data from Berlin’s Addiction Care Statistical Service (Suchthilfe Berlin) was used to calculate correction factors that make it possible to convert the DSHS data on treatment episodes step by step to individual-related data and to extrapolate it to the target group of individuals not given substitution treatment in each individual type of addiction care facility. Because the number of individuals addicted to opioids was to be estimated, only individuals or treatment episodes with a main or secondary diagnosis of opioid dependency (ICD/10 code F11) were included.

Corrections were performed separately for each facility type (type 2, types 3 to 4, types 8 to 10), for men and for women. Next, overlaps between inpatient and outpatient facilities were taken into account.

Overlaps between secondary diagnoses F11

Problem (DSHS)

Both primary diagnosis and secondary diagnoses were recorded for all individuals. Secondary diagnoses F11 fell into four categories:

One person was allocated a primary diagnosis but not only one of the four secondary diagnoses. For secondary diagnoses, one person may therefore have been included multiple times. This means the total number of treatment episodes within one primary diagnosis of the four F11 secondary diagnoses was higher, so the figures had to be corrected for secondary diagnoses F11.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For each primary diagnosis (F10 to F19, F50, F63, no primary diagnosis), the arithmetic mean of the number of treatment episodes for secondary diagnoses F11 was calculated as a correction factor.

Correction (DSHS)

The number of treatments for main or secondary diagnosis F11 was adjusted in the DSHS data using the above-mentioned correction factor, with stratification by primary diagnosis. For example, if a total of 96 treatment episodes had been recorded for primary diagnosis F10 with secondary diagnosis F11 but there were 108 treatment episodes altogether for the four secondary diagnoses F11, the correction factor 96/108 = 0.89 was calculated. This was then applied to the relevant DSHS figures and multiplied by the total number of treatment episodes for the four secondary diagnoses F11. This meant that the number of treatment episodes per primary diagnosis could be estimated without the influence of secondary diagnoses F11.

Indication

Individuals may also have been treated for different primary diagnoses at different facilities or during different treatment episodes. This was not taken into account in the corrections, as the inclusion of all possible combinations of multiple primary diagnoses for small patient numbers might have led to major bias. In the Berlin Addiction Care Statistical Service data, for example, multiple primary diagnoses (including “no primary diagnosis”) were more frequent in outpatient facilities: for one individual there were a total of 4 different primary diagnoses in the treatment year, for 50 individuals there were 3 primary diagnoses, and for 1232 individuals there were 2 primary diagnoses. Almost all possible diagnoses were present in different combinations (a precise list of all combinations cannot be included here for reasons of space). Essentially, 31 primary diagnoses were recorded using KDS 2.0 (“KDS” stands for Kerndatensatz, the German for “main dataset” and is the DSHS recording system for 2016). The total number of combinations of 2 and 3 primary diagnoses is more than 30 000 (312 + 313 = 30 752) even though patient numbers are small in each case.

DSHS coverage rate

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data does not cover all addiction care facilities in Germany, so it records only a certain proportion of the total number of treatment episodes. This means the number of treatment episodes recorded in the DSHS data has to be extrapolated to the total number of treatment episodes in Germany.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For each line in the table the coverage rate is calculated using the Süß und Pfeiffer-Gerschel method (16) for both inpatient and outpatient facilities. In 2016 the coverage rate was 73.38% for outpatient facilities and 61.61% for inpatient facilities. The calculations are based on the data of the central Registry of Addiction Care Facilities maintained by the German Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (DBDD, Deutsche Beobachtungsstelle für Drogen und Drogensucht) and funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Health.

Correction (DSHS)

The number of treatment episodes stated was extrapolated to the total number of treatment episodes in Germany (100%) using each coverage rate (73.88% for outpatient facilities, 61.61% for inpatient facilities).

Mean number of treatment episodes per person

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data may include individuals multiple times for multiple treatment episodes. This increases the total number of all treatment episodes within one primary diagnosis. This means the number of treatment episodes per person needs to be corrected.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

The mean number of treatment episodes for all individuals was stratified by primary diagnosis. This figure was between 1.00 and 1.12 treatment episodes person.

Correction (DSHS)

Using this correction factor, the number of treatment episodes stratified by sex was converted to the number of individuals treated at each facility type.

Percentage of people not given substitution treatment

Problem (DSHS)

The DSHS data contains no explicit information on whether individuals were also undergoing substitution treatment during a treatment episode. This means the percentages of individuals who did or did not undergo substitution treatment needs to be estimated.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals with a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or with primary diagnosis F11, it was ascertained whether one or more substitution treatments (substance prescription) or psychosocial treatments concomitant with substitution treatment had been administered during the treatment year. This, in turn, provided information on the percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment. This percentage ranged from 69.1% to 100%.

Correction (DSHS)

The percentage of individuals not given substitution treatment was used to calculate the number of individuals not given substitution treatment as a percentage of the estimated total figure.

Overlaps between outpatient facilities

Problem (DSHS)

Individuals may have been counted multiple times for facilities of type 2 and types 3 to 4 if they attended facilities of different types. This means correction for multiple inclusions in different facilities must be performed.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment, who had a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or a primary diagnosis F11, and who attended type 3 or 4 facilities, it was ascertained whether treatment episodes had also been reported in type 2 facilities. This yields a percentage of individuals treated in type 2 facilities who were included multiple times. The percentage was 0% for most primary diagnoses but in individual cases was as high as 82% (F12) or 100% (F10).

Correction (DSHS)

The estimated percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment in type 2 facilities was therefore corrected to remove multiple counts due to treatment episodes in type 3 or 4 facilities.

Overlaps between inpatient and outpatient facilities

Problem (DSHS)

Individuals may have been documented multiple times due to treatment episodes in both inpatient and outpatient facilities. This means the data needs to be corrected to remove multiple counts in both inpatient and outpatient facilities.

Correction factor (Berlin data)

For all individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment and with a primary diagnosis associated with secondary diagnosis F11 or primary diagnosis F11, the percentage of individuals who attended both outpatient facilities (types 2, 3, and 4) and inpatient facilities (types 8, 9, and 10) was calculated.

Correction (DSHS)

The percentage of individuals who did not undergo substitution treatment and who attended both inpatient and outpatient facilities was applied to the number of individuals in outpatient facilities and thus reduced the number of individuals in outpatient facilities. This percentage ranged from 0% to 100% (the latter included F13, F14, F19, and others).

Individuals addicted to opioids, not given substitution treatment, and receiving addiction care

In order to obtain the total number of individuals addicted to opioids, the estimated figures per primary diagnosis were added together, by sex and overall.

Heroin addiction

Methadone addiction

Buprenorphine addiction

Addiction to other opiate-containing drugs