Abstract

Background: Being diagnosed with cancer and undergoing its treatment are associated with substantial distress that can cause long-lasting negative psychological outcomes. Resilience is an individual’s ability to maintain or restore relatively stable psychological and physical functioning when confronted with stressful life events and adversities. Posttraumatic growth (PTG) can be defined as positive life changes that result from major life crises or stressful events.

Objectives: The aims of this study were to 1) investigate which factors can strengthen or weaken resilience and PTG in cancer patients and survivors; 2) explore the relationship between resilience and PTG, and mental health outcomes; and 3) discuss the impact and clinical implications of resilience and PTG on the process of recovery from cancer.

Methods: A literature search was conducted, restricted to PubMed from inception until May 2018, utilizing the following key words: cancer, cancer patients, cancer survivors, resilience, posttraumatic growth, coping, social support, and distress.

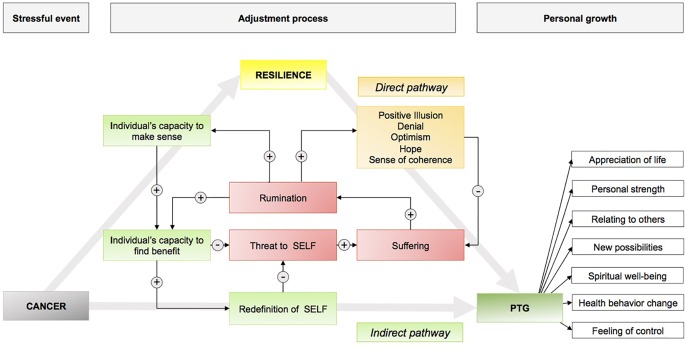

Results: Biological, personal, and most importantly social factors contribute to cancer patients’ resilience and, consequently, to favorable psychological and treatment-related outcomes. PTG is an important phenomenon in the adjustment to cancer. From the literature included in this review, a model of resilience and PTG in cancer patients and survivors was developed.

Conclusions: The cancer experience is associated with positive and negative life changes. Resilience and PTG are quantifiable and can be modified through psychological and pharmacological interventions. Promoting resilience and PTG should be a critical component of cancer care.

Keywords: cancer, resilience, coping, social support, distress, posttraumatic growth

Introduction

For many cancer patients, receiving a diagnosis of cancer and undergoing its treatment together comprise an extremely stressful experience that can render individuals vulnerable to long-lasting negative psychological outcomes, including emotional distress, depression, anxiety, sleep problems, fatigue, and impaired quality of life (1–5). Cancer is commonly perceived as a life-threatening and potentially traumatic illness, perceptions exacerbated by its sudden onset and uncontrollable nature (6). Furthermore, cancer patients must deal with dramatic life changes to which they have to adapt throughout their treatment trajectory (7). Research published in recent decades has emphasized the traumatic characteristics of a life-threatening illness, like cancer, and demonstrated how cancer patients exhibit responses consistent with psychological trauma (8–11). While in the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (12) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (13), life-threatening cancer was acknowledged to be a severe stressor that can trigger posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in the newest edition, the DSM-5, “a non-immediate, non-catastrophic life-threatening illness,” like cancer, is no longer qualified as traumatic, irrespective of how stressful or serious it is (14).

Interestingly, despite substantial distress that is associated with a cancer diagnosis and its treatment, many cancer patients manifest remarkable resilience (15, 16). Studies have shown that overcoming cancer and its treatment can be an opportunity for personal growth, as well as for enhanced mental and emotional well-being that could potentially be linked to better coping with disease-related demands (17–19). However, not everyone reacts to adversities in the same way, with some more resilient than others (20). Understanding which factors discriminate cancer patients, as well as cancer survivors who experience psychological growth from those who do not, might have important clinical implications and guide interventions to assist cancer patients and survivors with their psychological recovery from the cancer experience.

For this article, we reviewed the literature on resilience and posttraumatic growth (PTG) in cancer patients and survivors, so as to better understand which psychosocial, disease-related, and contextual factors yield better adjustment to the disease. The overall aims of this review were to 1) investigate which factors can strengthen or weaken resilience and PTG in cancer patients and survivors; 2) explore the relationships between resilience and PTG, and mental health outcomes; and 3) discuss the impact of resilience and PTG on the process of recovery from the disease, as well as the clinical implications of this impact.

For the purposes of this review, a literature search was conducted, restricted to PubMed articles from inception (1979) until May 2018, using the following search terms in various combinations: cancer, cancer patients, cancer survivors, resilience, posttraumatic growth, coping, social support, and distress. Only studies involving patients who were adults (≥18 years) were included. To be considered for the review, articles had to be peer reviewed and written in English ( Table 1 ). The psychometric instruments used in the eligible studies are summarized in Table 2 . From the literature reviewed, a two-pathway model of resilience in cancer patients and cancer survivors was drafted ( Figure 1 ).

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the review.

| Author, date | Title | Study design | Sample size | Outcome measures | Outcome | |

| 1 | Affleck and Tennen (21) | Construing benefits from adversity: adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings | Review article | – | – | Article summarizes the adaptive significance of finding benefits from major medical problems and examines how this process may be shaped by specific psychological dispositions such as optimism and hope and broader personality traits such as extraversion and openness to experience. |

| 2 | Aflakseir et al. (22) | The role of psychological hardiness and marital satisfaction in predicting posttraumatic growth in a sample of women with breast cancer in Isfahan | Cross-sectional study design | 120 breast cancer patients | PTGI EMS Ahvaz Psychological Hardiness Scale |

The majority of breast cancer patients experienced posttraumatic growth. Psychological hardiness, marital satisfaction, and longer time since cancer diagnosis predicted posttraumatic growth. |

| 3 | Amstadter et al. (23) | Personality, cognitive/psychological traits and psychiatric resilience: a multivariate twin study | Retrospective study design | SCL-90 Life Orientation Test Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

To determine the phenotypic relationships, and etiologic underpinnings, of cognitive/psychological traits (neuroticism, optimism, self-esteem, mastery, interpersonal dependency, altruism) with psychiatric resilience. | |

| 4 | Andrykowski et al. (24) | Lung cancer diagnosis and treatment as a traumatic stressor in DSM-IV and DSM-5 | Cross-sectional study design | 189 lung cancer survivors | SF-36 HADS DTherm PSS PTGI Benefit Finding Questionnaire |

Using the DSM-IV criterion, the trauma group (n = 70) reported poorer status than did the no trauma group (n = 119) on 10 of 10 distress indices (mean ES = 0.57 SD) and better status on all seven growth/benefit-finding indices (mean ES = 0.30 SD). Using the DSM-5 stressor criterion, differences between the trauma (n = 108) and no trauma (n = 81) groups for indices of distress (mean ES = 0.26 SD) and growth/benefit-finding (mean ES = 0.17 SD) were less pronounced. |

| 5 | Antonovsky (25) | Health, stress and coping | Book chapter | – | – | Antonovsky explains in greater detail how the sense of coherence affects health. He brings together recent studies on health and illness and shows their relationships to the sense of coherence concept. He presents a complete questionnaire that professionals can use to measure the sense of coherence and discusses the evidence for its validity. Moreover, he explores the neurophysiological, endocrinological, and immunological pathways through which the sense of coherence influences health outcomes. |

| 6 | Antonovsky (25) | Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well | Book chapter | – | – | A classic study of what allows people to be resilient in the face of stress, a concept coined “salutogenesis.” Using clinical practice and qualitative research methods, Antonovsky shows in fact how people can overcome serious challenges and identified the resources that people employ to resist illness and maintain their health in a world where stressors are ubiquitous. A key factor in assisting people to manage stress and resist illness is a “sense of coherence.” |

| 7 | Barskova et al. (26) | Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health | Systematic review | 68 empirical studies | – | The majority of the studies investigated PTG and its relationships to health indicators after the diagnosis of cancer, HIV/AIDS, cardiac disease, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. The review indicated that quality of social support, patients’ coping strategies, and several indicators of mental and physical health were consistently associated with posttraumatic growth. |

| 8 | Bergerot et al. (1) | Course of distress, anxiety, and depression in hematological cancer patients: association between gender and grade of neoplasm | Prospective study design | 104 hematologic cancer patients | Dtherm Problem List HADS |

Female patients reported more distress, anxiety, and depression than male patients did. Over the course of chemotherapy, the distress levels of patients with hematological cancer decrease over time. |

| 9 | Blank and Bellizzi (27) | After prostate cancer: predictors of well-being among long-term prostate cancer survivors | Cross-sectional study design | 490 prostate cancer patients | MIDI Control Scale LOT-R HHI COPE PANAS CES-D IES |

Although longer-term survivorship of prostate cancer patients does not appear to be a highly traumatic experience, personality factors and the use of coping strategies years after treatment were found to introduce variability to well-being in complex ways, differing in relation to positive and negative outcomes. |

| 10 | Boehmer et al. (28) | Coping and quality of life after tumor surgery: personal and social resources promote different domains of quality of life | Prospective study design (1 month and 6 months after surgery) | 175 gastrointestinal, colorectal, and lung cancer patients | General Self-efficacy Scale Coping Scale Berlin Social Support Scale EORTC-QLQ-30 |

Structural equation models indicate that self-efficacy at 1 month after surgery exerted a positive direct effect on patients’ physical, emotional, and social well-being of life at 6 months after surgery, but indirect effects through active and meaning-focused coping were also observed. Initial received support elevated later emotional well-being |

| 11 | Bonanno (29) | Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? | Review article | – | – | The author reviews evidence that resilience represents a distinct trajectory from the process of recovery, that resilience in the face of loss or potential trauma is more common than is often believed, and that there are multiple and sometimes unexpected pathways to resilience. |

| 12 | Bonanno et al. (12) | Grief processing and deliberate grief avoidance: a prospective comparison of bereaved spouses and parents in the United States and the People’s Republic of China | Prospective study design (4 and 18 months of bereavement) | 68 US participants 78 PRC participants |

13-item Grief Processing Scale 7-item Grief Avoidance Scale SCL-90 |

Both grief processing and deliberate grief avoidance predicted poor long-term adjustment for U.S. participants. |

| 13 | Bonanno et al. (30) | Resilience to loss and potential trauma | Review article | – | – | This review focuses on the heterogeneity of outcomes following aversive events, showing that resilience is not the result of a few dominant factors, but rather that there are multiple independent predictors of resilient outcomes. Typically, the most common outcome following posttraumatic events is a stable trajectory of healthy functioning or resilience. |

| 14 | Breitbart et al. (31) | Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: a randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer | Prospective study design | 321 patients with advanced cancer | FACIT-Sp LAP-R MQOL HADS SAHD |

Significant treatment effects (small to medium in magnitude) were observed for individual meaning-centered psychotherapy, relative to standard care, for quality of life, sense of meaning, spiritual well-being, anxiety, and desire for hastened death. |

| 15 | Brewin et al. (32) | Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults | Meta-analysis | 85 articles | – | Three categories of risk factors emerged: 1) small predictive effect on PTSD: gender, age at trauma, race; 2) moderate predictive effect on PTSD: education, previous trauma, childhood adversity; 3) large predictive effect on PTSD: psychiatric history, reported childhood abuse, and family psychiatric history. |

| 16 | Bruscia et al. (33) | Predictive factors in the quality of life of cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 49 patients with different cancer types | QOLS SOC-13 |

SOC multiple regressions showed that SOC was a significant predictor of QOL and that the demographic variables were not predictive of QOL, except when combined with SOC. |

| 17 | Calhoun et al. (34) | Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research & practice | Book chapter | – | – | Calhoun and Tedeschi bring together the leading theoreticians, researchers, and practitioners in the subdiscipline of posttraumatic growth. The importance of this field is that it already includes a rich history of empirical research demonstrating that posttraumatic growth can be operationalized, assessed, and enhanced. |

| 18 | Campbell-Sills and Stein (35) | Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience | Cross-sectional study design | 500 individuals | CD-RISC | The 10-item CD-RISC displays excellent psychometric properties with good internal consistency and construct validity and allows for efficient measurement of resilience. |

| 19 | Carver (15) | Resilience and thriving: issues, models and linkages | Review article | – | – | Thriving (physical or psychological) may reflect decreased reactivity to subsequent stressors, faster recovery from subsequent stressors, or a consistently higher level of functioning. Psychological thriving may reflect gains in skill, knowledge, confidence, or a sense of security in personal relationships and resembles other instances of growth. |

| 20 | Carver and Antoni (36) | Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis | Cross-sectional study design; follow-up between 4 and 7 years | 230 early stages breast cancer patients | CES-D | Controlling for initial distress and depression, initial benefit finding in this sample predicted lower distress and depression at follow-up. |

| 21 | Carver et al. (37) | How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer | Prospective study design | 59 breast cancer patients | LOT COPE POMS20 |

Optimism related inversely to distress at each point, even controlling for prior distress. Acceptance, positive reframing, and use of religion were the most common coping reactions; denial and behavioral disengagement were the least common reactions. Acceptance and the use of humor prospectively predicted lower distress; denial and disengagement predicted more distress. |

| 22 | Carver et al. (38) | Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes | Prospective study design | 163 early stage breast cancer patients | QLACS LOT ISEL |

Initial chemotherapy and higher stage predicted greater financial problems and greater worry about appearance at follow-up. Being partnered at diagnosis predicted many psychosocial benefits at follow-up. Hispanic women reported greater distress and social avoidance at follow-up. Initial trait optimism predicted diverse aspects of better psychosocial QOL at follow-up. |

| 23 | Chan et al. (20) | The strength-focused and meaning-oriented approach to resilience and transformation (SMART): a body–mind–spirit approach to trauma management | Research article | – | – | The article introduces the Strength-focused and Meaning-oriented Approach to Resilience and Transformation (SMART) as a model of crisis intervention, which aims at discovering inner strengths through meaning reconstruction. Efficacy of the SMART model is assessed with reference to two pilot studies conducted in Hong Kong at the time when the SARS pandemic caused widespread fear and anxiety in the community. |

| 24 | Chan et al. (8) | Course and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in a cohort of psychologically distressed patients with cancer | Prospective study design | 469 patients of various cancer types | HADS SCID-I |

The overall rates of PTSD decreased with time, but one-third of patients (34.1%) who were initially diagnosed had persistent or worsening PTSD 4 years later. |

| 25 | Cohen et al. (39) | The association of resilience and age in individuals with colorectal cancer: an exploratory cross-sectional study | Cross-sectional study design | 92 patients with colorectal cancer | The Wagnild and Young’s Resilience Scale BSI-18 Cancer-related problem list |

Older age, male gender, and less cancer-related problems were associated with higher resilience and lower emotional distress. |

| 26 | Connor (40) | Assessment of resilience in the aftermath of trauma | Review article | – | – | Resilience is a crucial component in determining the way in which individuals react to and deal with stress. A broad range of features is associated with resilience; these features relate to the strengths and positive aspects of an individual’s mental state. In patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, resilience can be used as a measure of treatment outcome, with improved resilience increasing the likelihood of a favorable outcome. |

| 27 | Connor et al. (41) | Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Prospective study design | Community sample, primary care outpatients, general psychiatric outpatients, clinical trial of generalized anxiety disorder, and two clinical trials of PTSD | CD-RISC | The scale demonstrated good psychometric properties and factor analysis yielded five factors. The scale demonstrates that resilience is modifiable and can improve with treatment, with greater improvement corresponding to higher levels of global improvement. |

| 28 | Cordova et al. (42) | Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer | Qualitative review | – | Cancer-related PTSD has been documented in a minority of patients with cancer and their family members, is positively associated with other indices of distress and reduced quality of life, and has several correlates and risk factors (e.g., prior trauma history, preexisting psychiatric conditions, poor social support). Existing literature on cancer-related PTSD has used DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria; the revised DSM-5 PTSD criteria have important implications for the assessment of cancer-related distress. | |

| 29 | Cormio et al. (43) | Posttraumatic growth and cancer: a study 5 years after treatment end | Cross-sectional study | 540 long-term disease free cancer survivors | PTGI MSPSS Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale STAI-Y |

The PTGI average total score was higher in more educated LCS, in those employed, in LCS with longer time from diagnosis, and in those with no comorbidities. In this study, PTG was not found correlated with distress, but it correlated with perceived social support, age, education, and employment. |

| 30 | Danhauer et al. (18) | A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute leukemia | Prospective study design | 66 leukemia patients | PTGI POMS-SF MDASI WHIIRS FACIT-Sp Cancer-related Rumination Scale Core Beliefs Inventory |

Findings suggest that these patients report PTG, and levels of PTG appear to increase over the weeks following leukemia diagnosis and induction chemotherapy. Variables associated with higher total PTG scores over time included greater number of days from baseline, younger age, and greater challenge to core beliefs. Variables associated with high. |

| 31 | Davidson et al. (44) | Trauma, resilience and saliostasis: effects of treatment in post-traumatic stress disorders | Prospective study design | 92 individuals with chronic PTSD | CD-RISC | Changes in resilience following treatment were statistically significant. Items that showed the greatest change related to confidence, control, coping, knowing where to turn for help and adaptability. Treatment of PTSD significantly improved resilience and reduced symptoms in this sample. Further controlled studies are indicated. |

| 32 | Davis et al. (45) | Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: two construals of meaning | Prospective qualitative study design | 280 bereaved individuals | Semi-structured interview | Results indicate that making sense of the loss is associated with less distress, but only in the first year postloss, whereas reports of benefit finding are most strongly associated with adjustment at interviews 13 and 18 months postloss. |

| 33 | Di Giacomo et al. (46) | Breast cancer and psychological resilience among young women | Prospective study design | 82 breast cancer patients | PDI STAXI STAY BDI-II |

Results highlight the psychological resilience in young women that have to deal with the breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Young patient seem more emotional resilient. |

| 34 | Diehl and Hay (47) | Personality-related risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress among adult cancer patients | Prospective study design (diary design + phone interviews) | 24 men with prostate cancer; 31 women with breast cancer | SCI PWB CES-D NEO-FFI Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale |

The findings from this study show the complex associations between risk and resilience factors and daily emotional well-being in a sample of adults who were affected by a life-threatening illness. |

| 35 | Dong et al. (48) | The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between social support and posttraumatic growth among colorectal cancer survivors with permanent intestinal ostomies: a structural equation model analysis | Cross-sectional study design | 164 colorectal cancer survivors | PTGI CD-RISC PSSS |

Perceived social support (r = 0.450) and resilience (r = 0.545) were significantly positively correlated with PTG. Structural equation modeling analysis showed that resilience mediated the relationship between perceived social support and PTG in which the indirect effect of perceived social support on PTG through resilience was 0.203 (P < 0001). |

| 36 | Duan-Porter et al. (49) | Physical resilience of older cancer survivors: an emerging concept | Prospective study design | 65 cancer survivors of different cancer types | BMI Endurance exercise Social support Adverse events |

The majority of older cancer survivors exhibited physical resilience; this was associated with high baseline health, physical function, self-efficacy, and social support. |

| 37 | Ebright and Lyon (50) | Understanding hope and factors that enhance hope in women with breast cancer | Prospective study design | 73 breast cancer patients | Lazarus’ Appraisal Components and Themes Scales HHI Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale Personal Resource Questionnaire 85-Part 2 Helpfulness of Religious Beliefs Scale |

Self-esteem and helpfulness of religious beliefs influence women’s appraisals regarding the potential for coping; appraisals and antecedent variables relevant for differentiating hope are beliefs about the potential for coping, self-esteem, and social support. |

| 38 | Eicher et al. (51) | Resilience in adult cancer care: an integrative literature overview | Review article | 11 articles | – | Resilience is a dynamic process of facing adversity related to a cancer experience. Resilience may be facilitated through nursing interventions. |

| 39 | Engeli et al. (52) | Resilience in patients and spouses faced with malignant melanoma. A qualitative longitudinal study | Prospective qualitative study design | 8 patients with malignant melanoma and their partners | Semistructured interview | There were no significant differences between the responses of patients and their partners. The most significant theme that emerged was manageability of disease, with distraction the most commonly utilized coping skill. The comprehension and meaning themes were far less prevalent. Hence, support should focus on disease and situational manageability. |

| 40 | Eriksson and Lindstrom (53) | Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review | A systematic review | 458 articles | – | SOC is strongly related to perceived health, especially mental health. This relation is manifested in study populations regardless of age, sex, ethnicity, nationality, and study design. SOC seems to have a main, moderating or mediating role in the explanation of health. Furthermore, the SOC seems to be able to predict health. |

| 41 | Erikson and Lindstrom (54) | Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review | A systematic review | 458 articles | – | The SOC scale seems to be a reliable, valid, and crossculturally applicable instrument measuring how people manage stressful situations and stay well. |

| 42 | Frazier et al. (55) | Posttraumatic growth: finding meaning through trauma | Book chapter | – | – | The article suggests that those individuals who perceive growth shortly after a stressful life event experience better mental health and fewer posttraumatic symptoms later. |

| 43 | Gall et al. (56) | The relationship between religious/spiritual factors and perceived growth following a diagnosis of breast cancer | Prospective study design | 93 breast cancer patients | Religious openness and participations Scale God Image Scale RCOPE |

Religious involvement at prediagnosis was predictive of less growth at 24 months postsurgery, while a positive image of God had no association with growth. |

| 44 | Goldberg et al. (57) | Factors important to psychosocial adjustment to cancer: a review of the evidence | Review article | – | – | This report reviews clinically noted or theoretically derived factors THAT have been tested empirically for relationships with various aspects of psychosocial adjustment. Certain specific cancer sites have been noted to be associated with psychosocial problems. A specific biological basis for psychiatric problems associated with certain diseases has been proposed for multiple myeloma, lung tumors, and pancreatic cancer. A number of chemotherapy agents are now recognized as accounting for presumed psychiatric symptoms |

| 45 | Gouzman et al. (16) | Resilience and psychosocial adjustment in digestive system cancer | Cross-sectional study design | 200 digestive system patients | Functional status, ECOG CD-RISC PANAS PTGI The Reported Behavior Changes Scale PAIS-SR |

Resilience, positive affect and negative affect, and posttraumatic growth were related to adjustment and/or reported behavioral changes, and positive affect, negative affect, and posttraumatic growth mediated some of the effects of resilience on adjustment and/or reported behavioral changes. |

| 46 | Groarke et al. (58) | Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer: how and when do distress and stress contribute? | Prospective study design | 253 breast cancer patients | Impact of Event Scale Perceived Stress Scale HADS Silver Lining Questionnaire |

This study showing that early-stage higher cancer-specific stress and anxiety were related to positive growth supports the idea that struggle with a challenging illness may be instrumental in facilitating PTG, and findings show positive implications of PTG for subsequent adjustment. |

| 47 | Gustavsson et al. (59) | Sense of coherence and distress in cancer patients and their partners | Prospective study design | 123 cancer couples | OLQ SOC-13 BDI-14 EMAS-State |

Strong SOC alleviated the development of distress. In addition, patient SOC tended to strengthen during the follow-up. All patient and partner variables at the 14-month follow-up were related to each other, but not at baseline. This could indicate a gradual crossover process of the shared experience. |

| 48 | Gustavsson et al. (60) | Predictors of distress in cancer patients and their partners: the role of optimism in the sense of coherence construct | Prospective study design | 147 cancer couples | LOT-R BDI-14 EMAS-State |

Optimistic patients and patients with strong SOC, as well as their partners, reported fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety than did less optimistic subjects and subjects with weaker SOC. Optimism partially explained the effect of SOC on distress and SOC seemed to be an independent factor in predicting distress. |

| 49 | Hamama-Raz (61) | Does psychological adjustment of melanoma survivors differs between genders? | Cross-sectional study design | 300 malignant melanoma survivors (≥5 years) | MHI Adaptation questionnaire Kessler’s Cognitive Appraisal of Health Scale Hardiness Scale Multi-Item Measure of Adult Attachment |

Women revealed more distress and less secondary cognitive appraisal and were more secure in attachment styles. Men showed higher secondary appraisal and were more dismissing-avoidant in attachment. |

| 50 | Helgeson et al. (62) | Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change | Cross-sectional study design | 287 women of breast cancer | SF-36 15-item Social Support Scale Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale 14-item Body Image Scale Illness Ambiguity Scale |

The majority of women showed slight and steady improvement in functioning with time, but subgroups of women were identified who showed marked improvement and marked deteriorations over time. Age distinguished different trajectories of physical functioning; personal resources (i.e., self-image, optimism, perceived control) and social support distinguished trajectories of mental and physical functioning. |

| 51 | Helmreich et al. (63) | Psychological interventions for resilience enhancement in adults | Review article | – | – | This is a protocol for a Cochrane Review (Intervention). The objectives are as follows: to assess the effects of resilience-enhancing interventions in clinical and nonclinical populations. |

| 52 | Henry et al. (64) | The meaning-making intervention appears to increase meaning in life in advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study | Prospective-study design | 24 cancer patients; 12 controls | MQOL FACIT-Sp HADS GSES |

Compared to the control group, patients in the experimental group had a better sense of meaning in life at 1 and 3 months postintervention. |

| 53 | Hou et al. (65) | Resource loss, resource gain, and psychological resilience and dysfunction following cancer diagnosis: a growth mixture modeling approach | Prospective-study design | 234 Chinese colorectal cancer patients | HADS | People in chronic distress were more likely to demonstrate loss in physical functioning and social relational quality but more likely to demonstrate stability/gain in optimistic personalities than those in delayed distress and resilient. |

| 54 | Hu et al. (66) | A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health | Meta-analysis | 60 studies included | – | Trait resilience was negatively correlated to negative indicators of mental health and positively correlated to positive indicators of mental health. Age, gender, and adversity moderated the relationship between trait resilience and mental health. |

| 55 | Hunter-Hernandez et al. (67) | Missed-opportunity: spirituality as a bridge to resilience in Latinos with cancer | Review article | – | – | For Latinos, spirituality is an important core cultural value. As such, it is crucial to pay close attention to how cultural values play a role in health-related concerns when caring for Latino cancer patients and to how spirituality, being an important aspect of Latino culture, influences how Latinos adjust and cope with cancer. |

| 56 | Husson et al. (68) | Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a longitudinal study | Prospective-study design | 169 cancer patients | PTGI PDS SF-36 BSI-18 |

This study indicates that posttraumatic growth is dynamic and predicts mental well-being outcomes but does not buffer the effects of posttraumatic stress. |

| 57 | Hwang et al. (69) | Factors associated with caregivers’ resilience in a terminal cancer care setting | Cross-sectional study design | 273 family caregivers | CD-RISC ECOG APGAR MOS-SSS CRA HADS |

High FCs’ resilience was significantly associated with FCs’ health status, depression, and social support. Education programs might be effective for improving caregivers’ resilience. |

| 58 | Jenewein et al. (70) | Quality of life and dyadic adjustment in oral cancer patients and their female partners | Cross-sectional study design | 31 cancer patients and their female partners | WHQOL-BREF HADS DAS EORTC QOL |

Quality of life was remarkably high in patients and their partners. In patients, lower QoL was associated with more physical complaints and higher levels of psychological distress (HADS), whereas in wives, QoL was found to be related to marital quality (DAS) and levels of distress. |

| 59 | Joseph et al. (71) | Assessing positive and negative changes in the aftermath of adversity: psychometric evaluation of the changes in outlook questionnaire (CiOQ) | Review article | – | CiOQ | The CiOQ has much promise for research on responses to stressful and traumatic events. |

| 60 | Kalisch et al. (72) | A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience | Review article | – | – | The theory emphasizes the causal role of stimulus appraisal (evaluation) processes in the generation of emotional responses, including responses to potential stressors. On this basis, it posits that a positive (nonnegative) appraisal style is the key mechanism that protects against the detrimental effects of stress. |

| 61 | Kernan et al. (73) | Searching for and making meaning after breast cancer: prevalence, patterns, and negative affect | Prospective study design | 72 breast cancer patients | PANAS 2 meaning questions |

The analyses reveal that (a) there is great variability in the prevalence and pattern of searching for meaning in the aftermath of breast cancer and (b) searching for meaning may be both futile and distressing. |

| 62 | Kobasa (74) | Stressful life events, personality, and health: an inquiry into hardiness | Prospective study design | 161 individuals | Holmes and Rahe Schedule of Recent Life Events Wyler, Masuda, and Holmes Seriousness of Illness Survey |

High stress/low illness executives show, by comparison with high stress/high illness executives, more hardiness, that is, have a stronger commitment to self, an attitude of vigorousness toward the environment, a sense of meaningfulness, and an internal locus of control. |

| 63 | Kraemer et al. (75) | A longitudinal examination of couples’ coping strategies as predictors of adjustment to breast cancer | Prospective study design | 139 couples | COPE Emotional Approach Coping scales SF-36 Vitality subscale CES-D IES-R PTGI |

Women’s use of approach-oriented coping strategies predicted improvement in their vitality and depressive symptoms, men’s use of avoidant coping predicted declining marital satisfaction for wives, and men’s approach-oriented strategies predicted an increase in women’s perception of cancer-related benefits. Patients’ and partners’ coping strategies also interacted to predict adjustment, such that congruent coping strategy use generally predicted better adaptation than did dissimilar coping. |

| 64 | Lam et al. (76) | Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer | Prospective study design | 285 early stage breast cancer patients | CHQ-12 TDM Breast Cancer Decision Making Questionnaire CLOT-R |

Psychologically resilient women had less physical symptom distress at early postsurgery compared with women with other distress patterns. Compared with the resilient group, women in the recovered or chronic distress groups experienced greater TDM difficulties, whereas women in the delayed-recovery group reported greater dissatisfaction with the initial medical consultation. Women in the chronic distress group reported greater pessimistic outlook. |

| 65 | Lam et al. (77) | Distress trajectories at the first year diagnosis of breast cancer in relation to 6 years survivorship | Prospective study design | 285 early-stage breast cancer | HADS Impact of Events Scale Chinese Social Adjustment Scale |

Women who experienced chronic distress had significantly greater longer-term psychological distress, cancer-related distress, and poorer social adjustment in comparison to women in the resilient group. |

| 66 | Lechner et al. (78) | Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer | Prospective study design | Two cohorts of 230 and 136 nonmetastatic breast cancer patient | CES-D Sickness Impact Profile |

Compared with the intermediate benefit finding (BF) group, low and high BF groups had better psychosocial adjustment. Further analyses indicated that the high BF group reported higher optimism and more use of positive reframing and religious coping than the other BF groups. |

| 67 | Lechner et al. (79) | Do sociodemographic and disease-related variables influence benefit-finding in cancer patients? | Cross-sectional study design | 83 cancer patients | PTGI-R The Perceived Threat Questionnaire NEO-FFI |

Individuals with stage II disease had significantly higher BF scores than those with stage IV or stage I cancer. Time since diagnosis and treatment status (i.e., currently in treatment, completed treatment, or no treatment) were not related to BF. |

| 68 | Lee (80) | The existential plight of cancer: meaning making as a concrete approach to the intangible search for meaning | Review article | – | – | Mounting evidence suggests that global meaning—defined as the general sense that one’s life has order and purpose—is a key determinant of overall quality of life. It provides the motivation for people with cancer to reengage in life amongst a bewildering array of physical, psychosocial, social, spiritual, and existential changes imposed by the disease. |

| 69 | Lee et al. (81) | Meaning-making intervention during breast or colorectal cancer treatment improves self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy | Prospective study design | 74 breast or colorectal cancer patients | Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale LOT-R GSES |

The experimental group participants demonstrated significantly higher levels of self-esteem, optimism, and self-efficacy compared to the control group. |

| 70 | Lelorain et al. (19) | Long-term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health | Cross-sectional study design | 307 disease-free breast cancer patients | PTGI SF-36 The Brief Cope PANAS |

Demographic and medical variables are poor predictors of posttraumatic growth. On the contrary, dispositional positive affectivity and adaptative coping of positive, active, relational, religious, and to some extent denial coping have a strong effect on posttraumatic growth. |

| 71 | Li et al. (82) | Effects of social support, hope and resilience on quality of life among Chinese bladder cancer patients: a cross-sectional study | Cross-sectional study design | 365 bladder cancer patients | FACT-BL, Perceived Social Support Scale Adult Hope Scale Resilience Scale-14 | Social support, hope, and resilience as a whole accounted for 30.3% variance of quality of life. |

| 72 | Lin et al. (10) | Risk factors of post-traumatic stress symptoms in patients with cancer | Cross-sectional study design | 347 cancer patients | Davidson Trauma Scale | The top four scores on Chinese version of Davidson Trauma Scale were painful memories, insomnia, shortened lifespan, and flashbacks. The risk factors of posttraumatic stress symptoms were suicidal intention (OR = 2·29, 95% CI = 1·86-2·82), chemotherapy (OR = 2·13, 1·18-3·84), metastasis (OR = 2·07, 1·29-3·34), cancer-specific symptoms (OR = 1·21, 1·15-1·27), and high education (OR = 1·75, 1·10-2·78). |

| 73 | Lindblad et al. (83) | Sense of coherence is a predictor of survival: a prospective study in women treated for breast cancer | Prospective study design | 487 breast cancer patients | SOC-13 | This study provides evidence of SOC’s predictive value for disease progression and BC-caused and all-cause mortality. |

| 74 | Linden et al. (2) | Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer types, gender, and age | Cross-sectional study design | 154 cancer patients | Psychosocial Screen for Cancer Questionnaire | Patients with lung, gynecological, or hematological cancer reported the highest levels of distress at the time point of cancer diagnosis. As expected, women showed higher rates of anxiety and depression, and for some cancer types, the prevalence was two to three times higher than that seen for men. Patients younger than 50 and women across all cancer types revealed either subclinical or clinical levels of anxiety in over 50% of cases. |

| 75 | Lindstrom and Erikson (84) | Salutogenesis | Review article | – | – | The aim of this paper is to explain and clarify the key concepts of the salutogenic theory sense of coherence coined by Aaron Antonovsky. |

| 76 | Linley and Joseph (85) | Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review | Review article | 39 empirical studies | – | The review indicated that cognitive appraisal variables (threat, harm, and controllability), problem-focused, acceptance and positive reinterpretation coping, optimism, religion, cognitive processing, and positive affect were consistently associated with adversarial growth. Inconsistent associations were found between adversarial growth, sociodemographic variables and psychological distress variables. |

| 77 | Lipsman et al. (86) | The attitudes of brain cancer patients and their caregivers toward death and dying: a qualitative study | Cross-sectional qualitative study design | 29 brain cancer patients; 22 partners | – | Participants found that their experiences, however difficult, led to the discovery of inner strength and resilience. Responses were usually framed within an interpersonal context, and participants were generally grateful for the opportunity to speak about their experiences. |

| 78 | Llewellyn et al. (87) | Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer | Prospective study design | 102 newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients | HADS LOT-R COPE SF-12 EORTC-QLQ |

Anxiety, depression, and quality of life were not related to benefit finding. Regression models of benefit finding total score and three new factor analyzed benefit finding scales indicated that use of emotional support and active coping strategies was predictive of finding more positive consequences. Optimism, living with a partner, and higher educational attainment were also found to have a protective effect on benefit finding. |

| 79 | Lo et al. (88) | Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): phase 2 trial of a brief individuals psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer | Prospective study design | 50 patients with advanced metastatic cancer | PHQ-9 FACIT-12 DADDS ECR-M16 PTGI |

Analyses revealed reductions over time in depressive symptoms and death anxiety and an increase in spiritual well-being. |

| 80 | Lo et al. (5) | Measuring death-related anxiety in advanced cancer: preliminary psychometrics of the Death and Dying Distress Scale | Cross-sectional study design | 33 patients with advanced metastatic cancer | DADDS | This distress was relatively common, with 45% of the sample scoring in the upper reaches of the scale, suggesting that the DADDS may be a relevant outcome for palliative intervention. |

| 81 | Loprinzi et al. (89) | Stress Management and Resilience Training (SMART) program to decrease stress and enhance resilience among breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial | Prospective study design | 20 breast cancer patients | CD-RISC Perceived Stress Scale, Smith Anxiety Scale, and Linear Analog Self-Assessment Scale |

A statistically significant improvement in resilience, perceived stress, anxiety, and overall quality of life at 12 weeks, compared with baseline, was observed in the study arm. |

| 82 | MacLeod et al. (90) | The impact of resilience among older adults | Review article | 55 articles | – | Research studies have identified the common mental, social, and physical characteristics associated with resilience. High resilience has also been significantly associated with positive outcomes, including successful aging, lower depression, and longevity. Interventions to enhance resilience within this population are warranted, but little evidence of success exists. |

| 83 | Maercker and Zoellner (91) | The Janus Face of Self-Perceived Growth: toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth | Review article | – | – | In the article, a two-component model of posttraumatic growth is presented to better understand the fascinating phenomenon of posttraumatic growth. |

| 84 | Mancini and Bonanno (92) | Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: toward an individual differences model | Review article | – | – | In this paper, we provide an operational definition of resilience as a specific trajectory of psychological outcome and describe how the resilient trajectory differs from other trajectories of response to loss. |

| 85 | Manne et al. (93) | Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: patient, partner, and couple perspectives | Prospective study design | 162 breast cancer patients and their partners | PTGI Impact of Events Scale COPE Emotional Processing Scale DAS |

Posttraumatic growth increased for both partners during this period. Patient posttraumatic growth was predicted by younger age, contemplating reasons for cancer, and more emotional expression at time 1. Partner posttraumatic growth was predicted by younger age, more intrusive thoughts, and greater use of positive reappraisal and emotional processing at time 1. |

| 86 | Manne et al. (94) | Resilience, positive coping, and quality of life among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers | Cross-sectional study design | 281 gynecological cancer patients | Block and Block’s scale Emotional Expressiveness Questionnaire COPE FACIT-Sp FACIT-G |

The findings suggested that resilient women may report higher quality of life during gynecological cancer diagnosis because they are more likely to express positive emotions, reframe the experience positively, and cultivate a sense of peace and meaning in their lives. |

| 87 | Markovitz et al. (95) | Resilience as a predictor for emotional response to the diagnosis and surgery in breast cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 253 breast cancer patients, 211 healthy controls | PTGI HADS PANAS 2 happiness items |

Higher levels of resilience were related to better emotional adjustment both in women with breast cancer and in control women, but this association was stronger within the sample of cancer patients. |

| 88 | Marosi and Köller (96) | Challenge of cancer in the elderly | Review article | – | – | The incidence of cancer is elevated 11-fold after the age of 65 years. Older adults present not only with the physiological decreases of organ functions related to age but also with an individual burden of comorbidities, other impairments, and social factors that might impact on their potential for undergoing cancer care. |

| 89 | Matzka et al. (97) | Relationship between resilience, psychological distress and physical activity in cancer patients. A cross-sectional observational study | Cross-sectional study design | 343 cancer patients | CD-RISC MSPSS Rotterdam Symptom Checklist |

Resilience was negatively associated with psychological distress and positively associated with activity level. The relationship between resilience and psychological distress was moderated by age but not social support. |

| 90 | Miller et al. (98) | Psychological distress and well-being advanced cancer: the effects of optimism and coping | Prospective study design | 75 advanced cancer patients | LOT-R Ways of Coping Questionnaire MHI CARES |

Optimism and coping were associated with psychological adjustment, even after controlling for functional status and prior adjustment. Optimism was strongly and positively associated with well-being and inversely related to distress. |

| 91 | Mizuno et al. (99) | Adaptation status and related factors at two time points after surgery in patients with gastrointestinal tract cancer | Prospective study design | 25 cancer patients | SOC-13 WHOQOL-26 |

Adaptation status 6 months (quality of life, sense of coherence, and illness related demands) after surgery improved compared with after discharge. |

| 92 | Moadel et al. (100) | Seeking meaning and hope: self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population | Cross-sectional study design | 248 cancer patients | Self-developed needs assessment survey | Patients (n = 7 1) reporting five or more spiritual/existential needs were more likely to be of Hispanic (61%) or African-American (41%) ethnicity (vs. 25% White), more recently diagnosed, and unmarried (49%) compared with those (n = 123) reporting two or fewer needs. Treatment status, cancer site, education, gender, age, and religion were not associated with level of needs endorsement. |

| 93 | Molina et al. (7) | Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives | Review article | – | – | For all phases of the cancer continuum, resilience descriptions included preexisting or baseline characteristics, such as demographics and personal attributes (e.g., optimism, social support); mechanisms of adaptation, such as coping and medical experiences (e.g., positive provider communication); and psychosocial outcomes, such as growth and quality of life. |

| 94 | Mols et al. (101) | Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors | Cross-sectional study design | 183 breast cancer survivors | PTGI Perceived Disease Impact Scale CentERdata Health monitor |

Benefit finding showed a moderately positive correlation with posttraumatic growth. In addition, women who stated that their satisfaction with life was high reported higher levels of posttraumatic growth in comparison to women who did not. Women with a higher tumor stage at diagnosis experienced less benefit finding in comparison to women with a lower tumor stage at diagnosis. |

| 95 | Morris and Shakespear-Finch (102) | Rumination, post-traumatic growth, and distress: structural equitation modeling with cancer survivors | Prospective study design | 313 cancer patients | PTGI IES-R COPE |

Trauma severity was directly related to distress, but not to PTG. Deliberately ruminating on benefits and social support was directly related to PTG. Life purpose rumination and intrusive rumination were associated with distress. |

| 96 | Mullen (103) | Sense of coherence as a mediator of stress for cancer patients and spouse | Prospective study design | 42 cancer patients, 32 spouses | SOC-13 SCL-K-9 FACIT-Sp |

Sense of coherence (SOC) was the only significant direct predictor of psychological stress. However, spiritual resources and family strengths had significant indirect paths through SOC as the mediator. |

| 97 | Mulligan et al. (104) | Cancer as a criterion A traumatic stressor for veterans: prevalence and correlates | Cross-sectional study design | 170 male patients | PC-PTSD | Approximately half—42.9% to 65.9%, depending on cut-score used—perceived cancer to be a traumatic stressor involving actual/threatened death or injury or threat to physical integrity as well as fear, helplessness, or horror. |

| 98 | Nuray and Asli (105) | Variables related to stress – related growth among Turkish breast cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 90 breast cancer patients | MSPSS WCI BDI SRGS |

Social support and problem-solving coping strategies related to higher levels of stress-related growth. |

| 99 | Pai et al. (14) | Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations | Review article | – | – | Changes to the diagnostic criteria from the DSM-IV to DSM-5 include the relocation of PTSD from the anxiety disorders category to a new diagnostic category named “Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders,” the elimination of the subjective component to the definition of trauma, the explication and tightening of the definitions of trauma and exposure to it, the increase and rearrangement of the symptoms criteria, and changes in additional criteria and specifiers. |

| 100 | Paika et al. (106) | Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients’ quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity | Cross-sectional study design | 162 colorectal cancer patients | SCL-90-R SOC-29 Life Style Index Hostility and Direction of Hostility Questionnaire |

In colorectal cancer patients, psychological distress and personality variables are associated with HRQOL independent of disease parameters. |

| 101 | Pan et al. (107) | Resilience and coping strategies influencing the quality of life in patients with brain tumor | Cross-sectional study design | 95 brain tumor patients | EORTC QLQ-BN20 Resilience Scale Ways of Coping Checklist-Revised |

Resilience accounted for 4.8% and the emotion-focused coping accounted for 10.20% of the variance in separately predicting the future uncertainty QOL. |

| 102 | Park (108) | Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events | Review article | – | – | Drawing on current theories, the author first presents an integrated model of meaning making. This model distinguishes between the two constructs “meaning-making efforts” and “meaning made.” Using this model, the author reviews the empirical research regarding meaning in the context of adjustment to stressful events. |

| 103 | Park et al. (109) | Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth | Review article | – | – | This article reports the development of the Stress-Related Growth Scale (SRGS). Significant predictors of the SRGS were (a) intrinsic religiousness, (b) social support satisfaction, (c) stressfulness of the negative event, (d) positive reinterpretation and acceptance coping, and (e) number of recent positive life events. The SRGS was also positively related to residual change in optimism, positive affectivity, number of socially supportive others, and social support satisfaction. |

| 104 | Park et al. (110) | Meaning-making and psychological adjustment following cancer: the mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs | Prospective study design | 172 cancer patients | Perceived Benefit Scale Medical Outcome Survey-Short Form |

Cross-sectional and longitudinal path models of the meaning making process indicate that meaning making efforts are related to better adjustment through the successful creation of adaptive meanings made from the cancer experience. |

| 105 | Park and Folkman (111) | Meaning in the context of stress and coping | Review article | – | – | The authors present a framework for understanding diverse conceptual and operational definitions of meaning by distinguishing two levels of meaning, global meaning and situational meaning. The functions of meaning in the coping process and importance of meaning making is reviewed and the critical role of reappraisal is highlighted. |

| 106 | Petersen et al. (112) | Relationship of optimism-pessimism and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors | Retrospective study design | 268 breast cancer patients | MMPI SF-36 |

Patients with a pessimistic explanatory style were significantly lower on all of the health-related QOL scores, compared to those with a nonpessimistic style. |

| 107 | Popa-Velea et al. (113) | Resilience and active coping style: effects on the self-reported quality of life in cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 178 cancer patients | COPE RS-14 Rotterdam Symptom Checklist |

Resilience correlated significantly with all quality of life components (global, physical distress, psychological distress, activity level), whereas active coping did it only indirectly, via resilience. Among other variables, occupational status and time from diagnosis correlated inversely to two of quality of life components, and TNM stage to all. |

| 108 | Post-White et al. (114) | Hope, spirituality, sense of coherence, and quality of life in patients with cancer | Systematic review | 26 research article | – | Four major themes emerged: (a) exploring the level of hope in patients with cancer, (b) discovering how patients cope with a cancer diagnosis, (c) identifying strategies that patients with cancer commonly use to maintain hope, and (d) identifying nursing interventions used to assist patients with cancer in maintaining and fostering hope. |

| 109 | Rajandram et al. (115) | Interaction of hope and optimism with anxiety and depression in a specific group of cancer survivors: a preliminary study | Cross-sectional study design | 50 cancer survivors | HADS Hope scale LOT-R |

Hope was negatively correlated with depression and anxiety. Regression analyses identified that both hope and optimism were significant predictors of depression. |

| 110 | Richardson (116) | The metatheory of resilience and resiliency | Review article | – | – | Resiliency and resilience theory is presented as three waves of resiliency inquiry. Practical paradigms of resiliency that empower client control and choice are suggested |

| 111 | Rodin et al. (4) | Pathways to distress: the multiple determinants of depression, hopelessness, and the desire for hastened death in metastatic cancer patients | Prospective study design | 406 patients with metastatic gastrointestinal or lung cancer | SOMC Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale ECR FACIT-SP-12 MSAS BPI Karnofsky Performance Status BHS BDI-II Schedule of Attitude Toward Hastened Death |

High disease burden, insecure attachment, low self-esteem, and younger age were risk factors for depression. Low spiritual well-being was a risk factor for hopelessness. Both depression and hopelessness independently predicted the desire for hastened death and mediated the effects of psychosocial and disease-related variables on this outcome. |

| 112 | Roen et al. (117) | Resilience for family carers of advanced cancer patients. How can health care providers contribute? | Cross-sectional qualitative study design | 14 carers of advanced cancer patients | – | Four main resilience factors were identified: (1) being seen and known by health care providers—a personal relation; (2) availability of palliative care; (3) information and communication about illness, prognosis, and death; and (4) facilitating a good carer–patient relation. |

| 113 | Rosenberg et al. (118) | Resilience, health, and quality of life among long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation | Cross-sectional study design | 4643 adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation | CD-RISC PTGI Cancer and Treatment Disease Measure SF-12 |

Lower patient-reported resilience was associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease of higher severity, lower performance scores, missing work because of health, and permanent disability. |

| 114 | Ruf et al. (119) | Positive personal changes in the aftermath of head and neck cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study in patients and their spouses | Cross-sectional qualitative study design | 25 cancer patients and their partners | – | Qualitative content analysis revealed three different categories of growth: attitudes toward life, personal strength, and relationships. Partners reported significantly more positive changes in relationships, especially, within the partnership. |

| 115 | Ruini et al. (17) | Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: new insights into its relationships with well-being and distress | Cross-sectional study design | 60 breast cancer patients; 60 healthy women | PTGI PWS Symptom Questionnaire Psychosocial Index |

Breast cancer patients reported significantly higher levels of PTG and distress and lower levels of PWB compared to healthy women. Breast cancer patients with high levels of PTG showed increased levels of physical well-being and decreased distress. |

| 116 | Saboonchi et al. (3) | Changes in caseness of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients during the first year following surgery: patterns of transiency and severity of the distress response | Prospective study design | 715 breast cancer patients | HADS | The average decrease in caseness of anxiety and depression a year following surgery lends support to the view of distress as a transient non-pathological response. A subgroup of patients, however, displayed enduring or recurrent severe distress indicating the presence of potential disorder. |

| 117 | Saleh and Brockopp (120) | Hope among patients with cancer hospitalized for bone marrow transplantation: a phenomenologic study | Cross-sectional qualitative study design | Nine patients hospitalized for bone marrow transplantation | – | The findings showed that participants used six strategies to foster their hope during preparation for BMT: feeling connected with God, affirming relationships, staying positive, anticipating survival, living in the present, and fostering ongoing accomplishment. Religious practices and family members were the most frequently identified sources of hope. |

| 118 | Scali et al. (121) | Measuring resilience in adult women using the 10-items Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Role of trauma exposure and anxiety disorders | Cross-sectional study design | 122 breast cancer patients; 116 healthy women | CD-RISC Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Watson’s Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Inventory |

Self-evaluation of resilience is influenced by both current anxiety disorder and trauma history. The independent positive association between resilience and trauma exposure may indicate a “vaccination” effect. |

| 119 | Schaefer and Moos (122) | Life crisis and personal growth. In: Personal coping. Theory, research and application | Review article | – | – | The article provides a better understanding of the positive consequences that can follow a life crisis and present a way to categorize health crisis and their consequences (divorce, physical illness, and bereavement), considering the environmental and personal determinants of positive outcomes and suggest ideas for research on the growth-promoting aspects of life crises. |

| 120 | Schofield et al. (123) | Hope, optimism and survival in a randomized trial of chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer | Cross-sectional study design | 429 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer | LOT-R State Hope Scale HADS EQ-5D |

Depression and health utility, but not optimism, hope, or anxiety, were associated with survival after controlling for known prognostic factors in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. |

| 121 | Schumacher et al. (124) | Resilience in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation | Cross-sectional study design | 75 patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation | Resilience-Scale 25 HADS General Self-efficacy Scale EORTC QLQ-C30 |

Resilience is positively correlated with quality of life and social functioning, negatively with anxiety and depression. Dividing the sample at the median resilience score of 144 reveals that high-resilience patients report less anxiety and depression; higher physical, emotional, and social functioning; and a better quality of life than low-resilience patients. |

| 122 | Sears et al. (125) | The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer | Prospective study design | 60 early stage breast cancer patients | PTGI HADS |

Positive reappraisal coping at study entry predicted positive mood and perceived health at 3 and 12 months and posttraumatic growth at 12 months, whereas benefit finding did not predict any outcome. Findings suggest that benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping, and posttraumatic growth are related, but distinct, constructs. |

| 123 | Siglen et al. (126) | The influence of cancer-related distress and sense of coherence on anxiety and depression in patients with hereditary cancer: a study of patients’ sense of coherence 6 months after genetic counseling | Cross-sectional study design | 96 patients referred to genetic counseling | SOC-29 HADS Impact of Event Scale |

Sense of coherence is significantly associated with both anxiety and depression. The hypothesis of Sense of Coherence buffering cancer-related distress and the possible impact of these findings for genetic counseling are discussed. |

| 124 | Silver et al. (127) | Searching for meaning in misfortune: making sense of incest | Review article | – | – | Article evaluates a study of 77 women who were victimized as children. The author tries to understand the following: (1) How important is the search of meaning after a crisis? (2) Are victims able to make sense of their aversive life experiences over time? (3) Does finding meaning in one’s victimization facilitate long-term adjustment to the event? (4) What are the implications of an inability to find meaning in life’s misfortunes? |

| 125 | Solano et al. (128) | Resilience and hope during advanced disease: a pilot study with metastatic colorectal cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 44 metastatic colorectal cancer patients | CD-RISC HHI Barthel Index |

Depressive patients had lower resilience and hope, and higher scores of suffering. The association between resilience and hope kept stable after adjusting for age, gender, and presence of depression. |

| 126 | Somasundaram and Devamani (129) | Comparative study on resilience, perceived social support and hopelessness among cancer patients treated with curative and palliative care | Cross-sectional study design | 66 cancer patients | Bharathiar University Resilience Scale Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Beck Hopelessness Scale |

Resilience was significantly associated with less hopelessness and higher levels of perceived social support. |

| 127 | Strang and Strang (130) | Spiritual thoughts, coping and sense of coherence in brain tumor patients and their spouse | Cross-sectional qualitative study design | 20 brain tumor patients; 16 spouses | – | Meaningfulness was central for quality of life and was created by close relations and faith, as well as by work. A crucial factor was whether the person had a “fighting spirit” that motivated him or her to go on. Sense of coherence integrates essential parts of the stress/coping model (comprehensibility, manageability) and of spirituality (meaning). |

| 128 | Strauss et al. (131) | The influence of resilience on fatigue in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy | Prospective study design | 108 cancer patients undergoing RT | Resilience Scale MFI SF-12 |

Fatigue was best predicted by the patients’ initial resilience scores. But resilience could not be determined as a predictor of changes in fatigue during RT. |

| 129 | Surtees et al. (132) | Sense of coherence and mortality in men and women in the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study | Prospective study design | 20’579 participants | SOC-13 | A strong sense of coherence was associated with a 30% reduction in mortality from all causes, cardiovascular, and cancer, independent of age, sex, and prevalent chronic disease. The association for all-cause mortality remained after adjustment for cigarette smoking history, social class, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, cholesterol, hostility, and neuroticism. Results suggest that a strong sense of coherence may confer some resilience to the risk of chronic disease. |

| 130 | Swartzman et al. (11) | Posttraumatic stress disorder after cancer diagnosis in adults: a meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | 11 research articles | – | PTSD, diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, is more common in survivors of cancer than it is in the general population. |

| 131 | Tagay et al. (133) | Protective factors for anxiety and depression in thyroid cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 230 thyroid cancer patients | HADS SOC-13 F-SOZU |

Our results support the thesis that low social support and low sense of coherence enhance vulnerability to depressive and anxiety symptoms. |

| 132 | Tang et al. (134) | Trajectory and determinants of the quality of life of family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients in Taiwan | Prospective study design | 167 family care givers | CQOLC | Taiwanese family care givers’ QOL deteriorated significantly as the patient’s death approached. |

| 133 | Taylor (135) | Adjustment to threatening events: a theory of cognitive adaptation | Review article | – | – | Proposes a theory of cognitive adaptation to threatening events. It is argued that the adjustment process centers around three themes: A search for meaning in the experience, an attempt to regain mastery over the event in particular and over life more generally, and an effort to restore self-esteem through self-enhancing evaluations. |

| 134 | Tedeschi and Calhoun (136) | Posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma | Validity and reliability study | – | – | The scale appears to have utility in determining how successful individuals, coping with the aftermath of trauma, are in reconstructing or strengthening their perceptions of self, others, and the meaning of events. |

| 135 | Tedeschi and Calhoun (137) | Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence | Review article | – | – | The authors propose a model for understanding the process of posttraumatic growth in which individual characteristics, support and disclosure, and more recently, significant cognitive processing play an important role. |

| 136 | Tedeschi and Calhoun (6) | Trauma and transformation: growing in the aftermath of suffering | Book chapter | – | – | The authors use a cognitive framework to explore this finding, focusing upon changes in belief systems reported by trauma survivors. Tedeschi and Calhoun weave together literature from fields as diverse as philosophy, religion, and psychology and incorporate major research findings into the effect of trauma |

| 137 | Thornton and Perez (138) | Posttraumatic growth in prostate cancer survivors and their partners | Prospective study design | 82 prostate cancer survivors; 67 partners | PTGI COPE PANAS IES SF-36 |

Higher levels of presurgery negative affect and coping by using positive reframing and emotional support were associated with higher levels of PTG 1 year following surgery. For partners, PTG 1 year after the patient’s surgery was higher in partners who were partnered to employed patients, were less educated, endorsed higher cancer-specific avoidance symptoms of stress at presurgery, and used positive reframing coping. Quality of life was largely unrelated to PTG in survivors or partners. |

| 138 | Tomich and Helgeson (139) | Five years later: a cross-sectional comparison of breast cancer survivors with healthy women | Cross-sectional study design | 174 breast cancer survivors; 328 healthy controls | World Assumption Scale FACIT-SP SF-36 PANAS Four self-developed questions for assessing meaning in life |

Survivors generally perceive the world as less controllable and more random compared to healthy women. Survivors also indicated that they derived some benefits from their experience with cancer, but these benefits had only a modest impact on quality of life. A continued search for meaning in life had a negative impact on quality of life. The strongest and most consistent correlate of quality of life for both survivors and healthy women was having a sense of purpose in life. |

| 139 | Tugade et al. (140) | Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health | Review article | Individual differences in psychological resilience are examined in two studies | – | Positive emotions can be an important factor that buffers individuals against maladaptive health outcomes. Finding ways to cultivate meaningful positive emotions is a critical necessity for optimal physical and psychological functioning. |

| 140 | Turner et al. (141) | Posttraumatic growth, coping strategies, and psychological distress in adolescent survivors of cancer | Cross-sectional study design | 31 adolescent cancer survivors | PTGI COPE |

Younger age at diagnosis and less use of avoidant coping strategies predicted lower levels of psychological distress. Adolescent cancer survivors who believe they are more prone to relapse and use more acceptance coping strategies are likely to have higher levels of posttraumatic growth. |

| 141 | Tzuh and Li (142) | The important role of sense of coherence in relation to depressive symptoms for Taiwanese family caregivers of cancer patients at the end of life | Cross-sectional study design | 253 Taiwanese family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients | CES-D SOC-13 |

Family caregivers scored high on the CES-D [mean (SD) = 22.24 (11.36)] |

| 142 | Vartak (143) | The role of hope and social support on resilience in cancer patients | Cross-sectional study design | 115 cancer patients | Herth Hope Scale The Brief Resilience Scale Perceived social support scale |

Hope and social support have a positive statistically significant impact on the resilience of cancer patients. |

| 143 | Wallston et al. (1447) | Social support and physical health | Review article | – | – | Article reviews the literature on social support and physical health, focusing on studies of illness onset; stress; utilization of health services; adherence to medical regimens; and recovery, rehabilitation, and adaptation to illness among human adults. |

| 144 | Walsh et al. (145) | A model to predict psychological- and health-related adjustment in men with prostate cancer: the role of post traumatic growth, physical post traumatic growth, resilience and mindfulness | Cross-sectional study design | 241 prostate cancer patients | Physical-PTGI PTGI |

P-PTGI predicted lower distress and improvement of quality of life, whereas conversely, the traditional PTG measure was linked with poor adjustment. |

| 145 | Weiss (146) | Correlates of posttraumatic growth in husbands of breast cancer survivors | Cross-sectional study design | 72 husbands of breast cancer patients | PTGI SSQ Quality of relationship inventory |

Significant predictors of husbands’ posttraumatic growth were depth of marital commitment, wife’s posttraumatic growth, and breast cancer meeting DSM-IV traumatic stressor criteria. |

| 146 | Wenzel et al. (147) | Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: a gynecologic oncology group study | Cross-sectional study design | 49 ovarian cancer patients | QOL-CS SF-36 FACIT-GOG/NTX |

Disease-free early-stage sample enjoys a good QOL, with physical, emotional, and social well-being comparable to other survivors and same-aged noncancer cohorts. However, 20% of survivors indicated the presence of long-term treatment side effects, with a subset reporting problems related to abdominal and gynecologic symptoms, and neurotoxicity. |

| 147 | Westphal et al. (148) | Posttraumatic growth and resilience to trauma: different sides of the same coin or different coins? | Review article | – | – | This article attempts to place PTG within a broader framework of individual differences in response to potential trauma. The authors argue that many, if not most, people are resilient in the face of trauma and that resilient outcomes typically provide little need or opportunity for PTG. |

| 148 | Wortman and Silver (149) | The myths of coping with loss revisited. In: Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care | Book chapter | – | – | In this chapter, the authors reviewed numerous studies that provide support for the assumption that most individuals can and do cope with loss and grief, without professional intervention. The article tries to address the question why some individuals show little distress shortly after their loss and also fail to show delayed grief reaction. |

| 149 | Wu et al. (9) | Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | 34 articles included | – | About 9.6% of the breast cancer patients would develop the PTSD symptoms. Those who were younger, non-Caucasian, and recently completed treatment would be at a greater risk of developing PTSD. |

| 150 | Ye et al. (150) | Predicting changes in quality of life and emotional distress in Chinese patients with lung, gastric, and colon-rectal cancer diagnosis: the role of psychological resilience | Cross-sectional study design | 276 cancer patients | Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 items Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

The present study suggests that psychological resilience is positively associated with QOL and may comprise a robust buffer between depression and QOL in Chinese patients with cancer. |