Abstract

Purpose

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer can have significant mental health ramifications. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently recommends using a distress screening tool to screen patients for distress and facilitate referrals to social service resources. Its association with radiation oncology–specific clinical outcomes has remained relatively unexplored.

Methods and materials

With institutional review board approval, National Comprehensive Cancer Network distress scores were collected for patients presenting to our institution for external beam radiation therapy during a 1-year period from 2015 to 2016. The association between distress scores (and associated problem list items and process-related outcomes) and radiation oncology–related outcomes, including inpatient admissions during treatment, missed treatment appointments, duration of time between consultation and treatment, and weight loss during treatment, was considered.

Results

A total of 61 patients who received either definitive (49 patients) or palliative (12 patients) treatment at our institution and completed a screening questionnaire were included in this analysis. There was a significant association between an elevated distress score (7+) and having an admission during treatment (36% vs 11%; P = .04). Among the patients treated with definitive intent, missing at least 1 appointment (71% vs 26%; P = .03) and having an admission during treatment (57% vs 10%; P = .009) were significantly associated with our institutional definition of elevated distress. We found no correlation between distress score and weight loss during treatment or a prolonged time between initial consult and treatment start.

Conclusions

High rates of distress are common for patients preparing to receive radiation therapy. These levels may affect treatment compliance and increase rates of hospital admissions. There remains equipoise in the best method to address distress in the oncology patient population. These results may raise awareness of the consequences of distress among radiation oncology patients. Specific interventions to improve distress need further study, but we suggest a more proactive approach by radiation oncologists in addressing distress.

Introduction

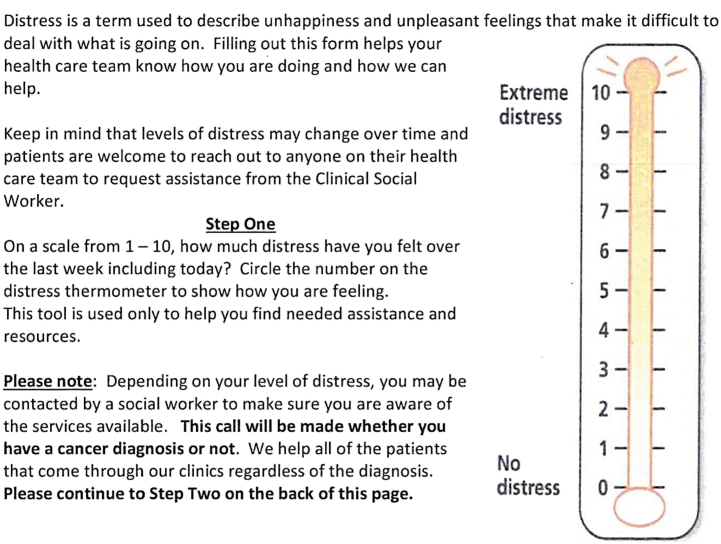

In 1997, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) established a multidisciplinary panel to examine how to integrate psychosocial care into routine cancer care.1 Malignancies have long been known to disrupt a patient's family, friendships, finances, and work life, and these disruptions are often difficult to recognize and address by providers.2, 3, 4 The NCCN Distress Thermometer is a tool that allows patients to score their level of distress on a scale of 0 to 10 (similar to the pain scale), with 0 being no distress and 10 being extreme distress. Physicians and others can use the tool to quickly identify patients with cancer who are experiencing distress and may benefit from intervention.

The tool includes a problem list on which patients can answer additional questions to help pinpoint the source of distress and allow for more targeted interventions. When the Distress Thermometer was originally released, a score of ≥4 was sufficient to trigger additional questioning and possible referral to psychosocial services.1 This tool has provided a way for providers to quickly screen patients for distress and additional psychosocial concerns.

Approximately a third of patients with cancer are estimated to experience a significant degree of distress, which varies by cancer site.5 High levels of distress on their own have been shown to be a poor prognostic factor,6, 7 but elevated distress levels may precipitate or exacerbate symptoms, such as loss of appetite, difficulty concentrating, and sleeplessness. These and other symptoms may undermine patients’ ability to fight their own diseases.8

Some efforts have been made to correlate distress with specific cancer outcomes. One study found that high distress levels measured before and during radiation therapy (RT) prognostic with higher distress levels associated with decreased survival.9

This retrospective study explores the association between distress scores and radiation oncology–specific outcomes. A secondary goal was to determine what factors could be contributing to worse outcomes in patients with high distress.

Methods and Materials

With institutional review board approval, we performed a retrospective review of our distress screening questionnaire and problem list (variation of the NCCN version; Fig 1) collected from 129 patients receiving treatment at the Department of Radiation Oncology when they presented for their initial consultation between 2015 and 2016. Of these patients, 38 questionnaires had insufficient information to be included in the analysis (ie, did not report a distress score). An additional 30 patients were excluded because they did not ultimately receive RT at our institution (ie, it was received elsewhere or refused), were treated with brachytherapy as monotherapy (eg, for prostate cancer), or were treated for a benign condition (eg, Duputyren's contracture). Of the 61 remaining patients, 49 were treated with definitive intent and 12 were treated with palliative (ie, noncurative) intent.

Figure 1.

Distress thermometer for patients. (adapted from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network)

We used Fisher's exact test and t tests to evaluate the association between distress score and radiation oncology–specific outcomes, including inpatient admissions during treatment, missed or canceled treatment appointments, duration of time between consultation and treatment, and weight loss during treatment. The policy established at our institution specifies that patients who report distress scores of ≥7 are considered high distress and trigger a social work consult. Therefore, we divided patients into 2 categories: low distress with scores of ≤6 and high distress with scores of 7 to 10.

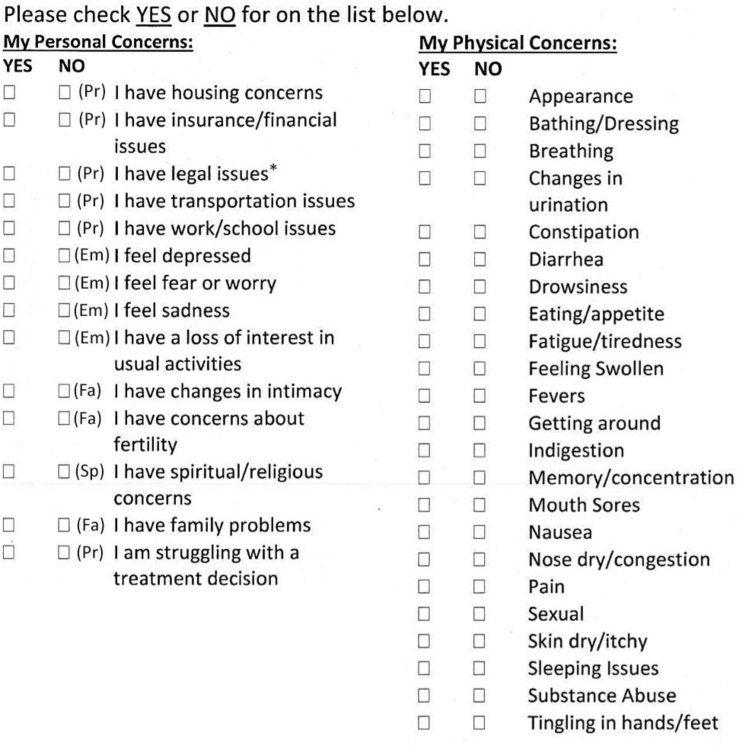

In addition to the ordinal 0-to-10 score, the NCCN scale also includes a problem list, which offers patients a yes/no response on 39 potential items that may have been problematic for the patient during the previous week. These items include practical problems, including child care and housing; family problems; emotional problems, such as depression; spiritual problems; and physical problems. Our institution makes minor modifications to this problem list (Fig 2). The overall number of reported problems was totaled according to their subsection of the problem list (ie, spiritual, family, practical, and physical). The breakdown of specific questions included in the categories is presented in Figure 2. Patients were given the option to check yes or no for each problem, but if a patient completed any of the problem list questions, missing answers were assumed to be no.

Figure 2.

Distress thermometer for patients (adapted from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network). Abbreviations: Em = emotional problem; Fa = family problem; Pr = practical problem; Sp = spiritual problem. All problems in the right column are classified as physical problems. *Problem list item used at our institution, but not in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tool.

Results

Of the 61 patients included, 44% were female and 72% were white. The most common malignancies were head and neck (31%), breast (20%), and genitourinary (15%), with all stages of disease represented (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and process-related characteristics of patients by distress level and treatment intent

| Patients treated with both palliative and definitive intent |

Patients treated with definitive intent |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Distress score 0-6 | Distress score 7-10 | P-value | Definitive patients | Distress score 0-6 | Distress score 7-10 | P-value | |

| Age, y | 60.0 (14.0) | 59.9 (13.6) | 60.3 (15.7) | .94 | 58.7 (14.4) | 58.1 (18.6) | 58.8 (13.9) | .91 |

| Female | 27 (44%) | 21 (45%) | 6 (43%) | 1 | 21 (43%) | 2 (29%) | 19 (45%) | .68 |

| Race | ||||||||

| African American | 17 (28%) | 14 (30%) | 3 (21%) | .54 | 13 (27%) | 1 (14%) | 12 (29%) | .41 |

| White | 44 (72%) | 33 (70%) | 11 (79%) | 35 (73%) | 6 (86%) | 29 (71%) | ||

| Stage | ||||||||

| I∗ | 7 (11%) | 6 (13%) | 1 (7%) | .018 | 6 (13%) | 1 (14%) | 5 (13%) | .24 |

| II | 15 (25%) | 15 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (35%) | ||

| III | 15 (25%) | 12 (26%) | 3 (21%) | 13 (28%) | 3 (43%) | 10 (25%) | ||

| IV | 24 (39%) | 14 (30%) | 10 (71%) | 14 (30%) | 3 (43%) | 11 (28%) | ||

| Cancer site | ||||||||

| Breast | 12 (20%) | 11 (23%) | 1 (7%) | .43 | 11 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (26%) | .18 |

| Central nervous system | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 6 (10%) | 4 (9%) | 2 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 1 (14%) | 4 (10%) | ||

| Genitourinary | 9 (15%) | 8 (17%) | 1 (7%) | 7 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (17%) | ||

| Gynecologic | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Head and neck | 19 (31%) | 14 (30%) | 5 (36%) | 19 (39%) | 5 (71%) | 14 (33%) | ||

| Hematologic | 5 (8%) | 4 (9%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| Sarcoma | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Skin | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Thorax | 4 (7%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| Treatment with palliative intent | 12 (20%) | 5 (11%) | 7 (50%) | .003 | ||||

| Process outcomes | ||||||||

| Days to start radiation therapy from consult | 50.7 (51.6) | 55.8 (55.6) | 33.7 (30.9) | .16 | 58.6 (54.1) | 53.0 (33.4) | 59.5 (57.1) | .77 |

| Change in weight (kg) | −2.6 (6.0) | −2.2 (5.3) | −4.5 (9.5) | .37 | −2.6 (6.0) | −4.5 (9.5) | −2.2 (5.3) | .37 |

| Any canceled treatments | 19 (31%) | 12 (26%) | 7 (50%) | .11 | 16 (33%) | 5 (71%) | 11 (26%) | .030 |

| Social work consultation | 20 (33%) | 13 (28%) | 7 (50%) | .19 | 16 (33%) | 5 (71%) | 11 (26%) | .030 |

| Admission during radiation therapy | 10 (16%) | 5 (11%) | 5 (36%) | .041 | 8 (16%) | 4 (57%) | 4 (10%) | .009 |

| Number of patients | 61 | 47 | 14 | 49 | 42 | 7 | ||

Includes one patient with Stage 0 breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ).

In our sample, patients who reported higher distress scores were more likely to present with higher stages of disease (P = .018). There was a significant association between a high distress score and admission during treatment (P = .041). Other demographic and clinical factors, including age, race, and cancer stage or site, were not correlated with distress levels in our sample. Likewise, no correlation was detected between distress score and amount of weight loss/gain, or the time between initial consult and start of treatment.

Table 2 explores the categories of problems that may underlie higher levels of distress. Overall, the average distress score of our sample was 3.8. Patients with higher levels of distress reported significantly more practical, emotional, family-related, and physical problems. Practical problems showed the largest disparity based on distress level, with the reported number of problems averaging 2.4 among those reporting distress scores of 7 to 10 versus 0.8 for those with distress scores of 0 to 6 (P = .003). The positive association between distress levels and these outcomes was robust to other cutoffs of distress scores (eg, >5). A multivariate analysis to adjust for the variables noted in Table 1 was considered, but the small sample size (especially for the clinical variables such as cancer site) would make these results less reliable.

Table 2.

Breakdown of problem list responses by distress level

| All patients | Distress score 0-6 | Distress score 7-10 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall distress score (0-10) | 3.8 (3.2) | 2.4 (2.1) | 8.3 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Number of practical problems | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.8) | .013 |

| Number of emotional problems | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.6) | <.001 |

| Number of family problems | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.8 (1.1) | .002 |

| Number of physical problems | 3.4 (4.6) | 2.3 (3.4) | 6.9 (6.2) | <.001 |

| Spiritual/religious problems | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (14%) | .22 |

| Number of patients | 61 | 47 | 14 |

Table 3 explores the breakdown for patients who missed or canceled any of their treatment appointments and those who experienced hospital admissions during their RT course. Overall, patients who canceled or missed RT appointments had, on average, nearly double the reported distress score compared with those who did not have any such missed or canceled appointments (4.9 vs 3.2; P = .047). The number of emotional problems and the number of physical problems were both associated with canceling or missing a treatment appointment. However, the remaining items of the problem list were not associated with the probability of a patient canceling or missing a treatment appointment. Patients who had a hospital admission during RT also reported elevated distress scores (3.4 vs 5.8; P = .024), but they were not more likely to report an increased number of practical, emotional, family, or physical problems.

Table 3.

Overall distress and problem list responses by missed treatment, hospital admission and palliative treatment intent

| Variable | Any canceled or missed treatments |

Any hospital admissions during treatment |

Palliative treatment intent |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P-value | No | Yes | P-value | No | Yes | P-value | |

| Overall distress score (0-10) | 3.2 (3.1) | 4.9 (3.1) | .047 | 3.4 (3.0) | 5.8 (3.5) | .024 | 3.2 (2.9) | 5.9 (3.4) | .007 |

| Number of practical problems | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.9) | .16 | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.6) | .47 | 0.6 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.9) | .064 |

| Number of emotional problems | 0.8 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.6) | .027 | 0.9 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.7) | .17 | 1.0 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.4) | .44 |

| Number of family problems | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.7) | .18 | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.7) | .6 | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.6 (1.2) | .11 |

| Number of physical problems | 2.4 (4.2) | 5.5 (4.9) | .015 | 3.2 (4.8) | 4.3 (3.1) | .49 | 2.8 (3.9) | 5.7 (6.6) | .054 |

| Spiritual/religious problems | 1 (2%) | 3 (16%) | .085 | 3 (6%) | 1 (10%) | .52 | 2 (4%) | 2 (17%) | .17 |

| Social work consultation | 11 (26%) | 9 (47%) | .14 | 14 (27%) | 6 (60%) | .066 | 16 (33%) | 4 (33%) | 1.00 |

| Number of patients | 42 | 19 | 51 | 10 | 49 | 12 | |||

When evaluating patients treated with definitive intent, a higher proportion of patients with higher distress scores received a social work consult (71% vs 26%; P = .030). When palliative and definitively treated patients were combined, there was no longer a significant difference in level of distress and likelihood of receiving a social work consult (50% vs 28%; P = .19). Overall, however, patients treated with palliative intent had significantly higher distress scores relative to those treated with definitive intent (5.9 vs 3.2; P = .007), and there was a weak association between palliative treatment intent and number of practical and physical problems (P < .10).

Discussion

This study identifies several practical issues surrounding the care of radiation oncology patients that may be more prevalent among patients with higher levels of distress at the time of initial consultation. Specifically, we find that higher levels of distress correlated with more missed appointments and more inpatient admissions during RT, especially among patients who received RT with definitive intent. Missed treatment appointments and inpatient admissions during treatment can prolong the duration of RT and possibly decrease the efficacy of treatment. For example, among head and neck cancer patients, each additional week of treatment prolongation was associated with a 14% reduction in local control.10 Similar findings of worse outcomes with treatment prolongation have been reported in prostate, cervical, lung, anal, bladder, and breast cancers.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Increased rates of hospitalization for patients with higher levels of distress may also signify additional health problems that need to be addressed more thoroughly in these patients.

To prevent hospitalizations and missed appointments among patients with higher levels of distress, distress must be detected early and addressed by a multidisciplinary care team. We found that social work was frequently involved for patients who reported high distress, though social work involvement on its own was not associated with our targeted outcomes. Addressing distress within the radiation oncology setting is complicated, and barriers to proper treatment include lack of training for clinicians and staff in the management of psychosocial issues, time constraints, and limited patient reporting.

The results of several studies have been inconclusive on effective methods to improve patient-reported distress. One previously proposed method involved caregivers having patients rank the top 4 issues that contribute to their distress and giving the patients options for how they would like to address them, including outside referral.17 Unfortunately, this method of addressing distress was shown to be cost ineffective and was not associated with improvement in patient mood states. There has been some success in nursing staff helping to address patient distress. In a study in which nurses received a training course before providing basic psychosocial care, minor interventions, and exploring referral possibilities for their patients, patients did report satisfaction with the nurses’ care, but no effect on depressive symptoms or quality of life was seen.18 A recent randomized controlled trial that evaluated brief psychosocial intervention for depressed patients with cancer concluded that it was insufficient as a stand-alone treatment.19

These studies show that more intensive and focused treatment is needed to help address patient distress. Sometimes this requires the involvement of another service that is equipped to address distress, such as psychiatry. Unfortunately, few patients desire referrals to other professionals, including <15% of patients who report high distress (score >5), and older patients are even less likely to desire referrals.20, 21, 22 Therefore, focusing on more training for radiation oncology professionals to address patients’ psychological needs seems prudent, but this is made more difficult by the stigma that surrounds psychosocial issues for both health care providers and patients, especially in the oncologic setting.23 Oncologists have been reported to be reluctant to address psychosocial issues in patients for fear of causing pain, harm, or additional distress, and one study showed that as many as 73% of depression cases are underrecognized by oncologists.24, 25

For radiation oncologists, recognizing a patient's psychological response to the stress of a cancer diagnosis and RT is important. These patients commonly use defense mechanisms, including denial and projection, which are important to identify because they can act as further barriers to understanding and treating patient distress.26 In the radiation oncology setting, addressing a patient's distress may be as simple as assuaging fears and misconceptions of RT, including concerns of becoming radioactive or impact on fertility.27 Understanding racial disparities in factors that drive distress, (eg, practical problems such as transportation) may also help identify mechanisms to alleviate distress.28 Simple training in communication skills and recognizing empathetic opportunities with a focus on behaviors that express support, sympathy, and compassion, can be effective in improving diagnosis and treatment of psychological issues.29, 30, 31

Increasing protected time to focus on patient distress is another key element.32 A guideline written to help psychiatric providers care for radiation oncology patients may also provide useful resources for radiation oncologists.33 This resource should discuss common causes of anxiety in these patients as well as medical and psychiatric medical techniques for management. Another article reviewed psychosocial interventions, including psychoeducation, cognitive-behavior therapy, and supportive-expressive therapy, that can be done in the RT clinic by training radiation oncologists and staff to be conductors.34 In this randomized controlled trial, these interventions were effective in reducing depression and anxiety in patients, although they did not reduce the risk of cancer recurrence or death.

Along with focusing on improving distress management in the RT clinic, it is equally important for radiation oncologists to recognize when patients need a referral to outside psychiatric services, especially in the setting of time constraints in the clinic that do not allow for more intensive care. Very elevated distress scores should raise concerns for the need to refer to outside services, with studies showing that 55% of patients with distress scores of 10 desire a referral. Patients with higher scores who did not desire a referral were more likely reluctant because of fears of negative impacts of psychosocial intervention rather than a true lack of need of support.20, 24 Even with this reluctance, most patients were found to highly value oncologists’ opinions of support services, and the majority were willing to accept a referral when offered.35, 36 Radiation oncologists should make outside providers aware of the special needs and issues of their patients undergoing RT and refer them to the aforementioned psychiatric guideline for radiation oncology patients.33 Outside referral has been shown to be effective, with outpatient psychosocial interventions improving outcomes in patients with cancer.37, 38 The benefits of outpatient psychotherapy have also been shown in the radiation oncology patient population.39, 40

Although our study found associations between elevated distress and missed RT appointments and hospitalizations, our analysis has several limitations. First, we looked at a combination of patients who were treated with definitive intent and palliative intent. When we analyzed only patients treated with definitive intent alone, we found a stronger association between distress scores and the likelihood of missing treatment appointments or being admitted to the hospital during treatment. When we analyzed our combined group of both palliatively and definitively treated patients, the likelihood of missing a treatment appointment or being admitted during treatment decreased, especially in our high-distress cohort. This could be attributable to the shorter treatment times of palliative treatment with fewer opportunities to miss an appointment or be admitted during treatment. Our analysis uses a relatively small sample size from a single institution, and a larger group of patients would provide better information about the association distress scores have with our targeted outcomes.

Furthermore, our institution is relatively unique in its role as a safety net hospital, and many patients receiving RT at our institution may have different factors driving their distress compared with the overall oncologic population at large. Along those lines, unobserved factors, such as socioeconomic status (education/income), may explain a portion of the effect of distress on these outcomes, although these patient characteristics are not typically available to clinicians. At our institution, there is a very large referral base from which head and neck cancer cases are captured, which skews our analysis somewhat to that treatment site compared with an average community radiation clinic, which may have less representation of patients with head and neck cancer.

Additionally, as discussed, our distress measures are collected at a single point in time before simulation or treatment. This single snapshot of patient distress does not give a complete picture of distress across the patients’ treatment course compared with more elaborate batteries conducted longitudinally. Finally, multiple patients who were offered a screening questionnaire did not complete it, which makes our analytical sample subject to bias related to selection.

Conclusions

Elevated distress continues to be a difficult problem to handle for many patients with cancer and for providers. Our study provides evidence that high levels of distress can affect radiation oncology–specific outcomes, leading to missed treatments, which may affect long term outcomes including locoregional control and survival. Overall, our findings underscore the need for radiation oncologists to be proactive in addressing patient distress to help decrease potential barriers to receiving treatment. Radiation oncologists may also need to involve several members of the health care team, such as social work, psychiatry, and other medicine subspecialties, early in the course of treatment to quickly and effectively address sources of distress and additional underlying health problems. However, the benefits of these strategies lack extensive evidence, and more attention and research are needed to develop guidelines on the best methods to reduce and manage patient distress and improve outcomes.

Footnotes

Meeting information: A previous version of this paper was presented at the American Society for Radiation Oncology Meeting on October 1, 2017.

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Holland J.C., Bultz B.D., National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2007;5:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisman A.D., Worden J.W. The existential plight in cancer: Significance of the first 100 days. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1977;7:1–15. doi: 10.2190/uq2g-ugv1-3ppc-6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassileth B.R., Lusk E.J., Brown L.L., Cross P.A., Walsh W.P., Hurwitz S. Factors associated with psychological distress in cancer patients. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1986;14:251–254. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950140503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Söllner W., DeVries A., Steixner E. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? Br J Cancer. 2001;84:179–185. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zabora J., BrintzenhofeSzoc K., Curbow B., Hooker C., Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert M.R., Dignam J.J., Armstrong T.S. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaasa S., Mastekaasa A., Lund E. Prognostic factors for patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer, limited disease. Radiother Oncol. 1989;15:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(89)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson L.E., Angen M., Cullum J. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habboush Y., Shannon R.P., Niazi S.K. Patient-reported distress and survival among patients receiving definitive radiation therapy. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017;2:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler J.F., Lindstrom M.J. Loss of local control with prolongation in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90768-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thames H.D., Kuban D., Levy L.B. The role of overall treatment time in the outcome of radiotherapy of prostate cancer: An analysis of biochemical failure in 4839 men treated between 1987 and 1995. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez C.A., Grigsby P.W., Castro-Vita H., Lockett M.A. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Impact of prolongation of overall treatment time and timing of brachytherapy on outcome of radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:1275–1288. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00220-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox J.D., Pajak T.F., Asbell S. Interruptions of high-dose radiation therapy decrease long-term survival of favorable patients with unresectable non-small cell carcinoma of the lung: Analysis of 1244 cases from 3 Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;27:493–498. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber D.C., Kurtz J.M., Allal A.S. The impact of gap duration on local control in anal canal carcinoma treated by split-course radiotherapy and concomitant chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:675–680. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciejewski B., Majewski S. Dose fractionation and tumour repopulation in radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1991;21:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(91)90033-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bese N.S., Sut P.A., Ober A. The effect of treatment interruptions in the postoperative irradiation of breast cancer. Oncology. 2005;69:214–223. doi: 10.1159/000087909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollingworth W., Metcalfe C., Mancero S. Are needs assessments cost effective in reducing distress among patients with cancer? A randomized controlled trial using the Distress Thermometer and Problem List. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3631–3638. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Meulen I.C., May A.M., Koole R., Ros W.J.G. A distress thermometer intervention for patients with head and neck cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45:E14–E32. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.E14-E32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner J., Kelly B., Clarke D. A tiered multidisciplinary approach to the psychosocial care of adult cancer patients integrated into routine care: The PROMPT study (a cluster-randomised controlled trial) Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves K.D., Arnold S.M., Love C.L., Kirsh K.L., Moore P.G., Passik S.D. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: Prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch J., Goodhart F., Saunders Y., O'Connor S.J. Screening for psychological distress in patients with lung cancer: Results of a clinical audit evaluating the use of the patient Distress Thermometer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuinman M.A., Gazendam-Donofrio S.M., Hoekstra-Weebers J.E. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: Use of the Distress Thermometer. Cancer. 2008;113:870–878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dilworth S., Higgins I., Parker V., Kelly B., Turner J. Patient and health professional’s perceived barriers to the delivery of psychosocial care to adults with cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:601–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.3474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okuyama T., Endo C., Seto T. Cancer patients’ reluctance to disclose their emotional distress to their physicians: A study of Japanese patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17:460–465. doi: 10.1002/pon.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner J., Zapart S., Pedersen K. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14:159–173. doi: 10.1002/pon.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porcerelli J.H., Cramer P., Porcerelli D.J., Arterbery V.E. Defense mechanisms and utilization in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: A pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:466–470. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillan C., Abrams D., Harnett N., Wiljer D., Catton P. Fears and misperceptions of radiation therapy: Sources and impact on decision-making and anxiety. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonagh P.R., Slade A.N., Anderson J., Burton W., Fields E.C. Racial differences in responses to the NCCN Distress Thermometer and Problem List: Evidence from a radiation oncology clinic. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27:2513–2516. doi: 10.1002/pon.4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallowfield L., Ratcliffe D., Jenkins V., Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–1015. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fogarty L.A., Curbow B.A., Wingard J.R., McDonnell K., Somerfield M.R. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollak K.I., Arnold R.M., Jeffreys A.S. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biddle L., Paramasivan S., Harris S., Campbell R., Brennan J., Hollingworth W. Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of holistic needs assessment using a cancer distress thermometer and problem list: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;23:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmes E.G., Holmes J.A., Park E.M. Psychiatric care of the radiation oncology patient. Psychosomatics. 2017;58:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Z., Tang H.Y., Li H. The benefits of psychosocial interventions for cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:121. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edgar L., Remmer J., Rosberger Z., Fournier M.A. Resource use in women completing treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2000;9:428–438. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200009/10)9:5<428::aid-pon481>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth A.J., Kornblith A.B., Batel-Copel L., Peabody E., Scher H.I., Holland J.C. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: A pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen B.L., Yang H.C., Farrar W.B. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2008;113:3450–3458. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giese-Davis J., Collie K., Rancourt K.M., Neri E., Kraemer H.C., Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hess C.B., Chen A.M. Measuring psychosocial functioning in the radiation oncology clinic: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:841–854. doi: 10.1002/pon.3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnur J.B., David D., Kangas M., Green S., Bovbjerg D.H., Montgomery G.H. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral therapy and hypnosis intervention on positive and negative affect during breast cancer radiotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:443–455. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]