Abstract

Background

Korea has a periodic general health check-up program that uses the Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition (KDSQ-C) as a cognitive dysfunction screening tool. The Alzheimer Disease 8 (AD8) and Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire (SMCQ) are also used in clinical practice. We compared the diagnostic ability of these screening questionnaires for cognitive impairment when completed by participants and their caregivers. Hence, we aimed to evaluate whether the SMCQ or AD8 is superior to the KDSQ-C and can be used as its replacement.

Methods

A total of 420 participants over 65 years and their informants were recruited from 11 hospitals for this study. The patients were grouped into normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia subgroups. The KDSQ-C, AD8, and SMCQ were completed separately by participants and their informants.

Results

A receiver operating characteristic analysis of questionnaire scores completed by participants showed that the areas under the curve (AUCs) for the KDSQ-C, AD8, and SMCQ for diagnosing dementia were 0.75, 0.8, and 0.73, respectively. Regarding informant-completed questionnaires, the AD8 (AUC of 0.93), KDSQ-C (AUC of 0.92), and SMCQ (AUC of 0.92) showed good discriminability for dementia, with no differences in discriminability between the questionnaires.

Conclusion

When an informant-report is possible, we recommend that the KDSQ-C continues to be used in national medical check-ups as its discriminability for dementia is not different from that of the AD8 or SMCQ. Moreover, consistent data collection using the same questionnaire is important. When an informant is not available, either the KDSQ-C or AD8 may be used. However, in the cases of patient-reports, discriminability is lower than that for informant-completed questionnaires.

Keywords: Cognition, Dementia, Self-Report, Self-Assessment, Questionnaire

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid increase in the elderly population in Korea, dementia has emerged as a major health problem.1 The Korean government has instituted a national screening program for transitional ages (NSPTA) that includes screening for cognitive dysfunction at ages 66, 70, and 74 years, and which has been covered by the National Health Insurance since 2007.2 The primary screening tool in the NSPTA to detect cognitive dysfunction has been The Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Prescreening (KDSQ-P), while The Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition (KDSQ-C) has been used for secondary screening.3 Although the KDSQ-P and KDSQ-C were designed to be completed by a reliable informant, these questionnaires are frequently completed by the patient him- or herself. Since 2018, the NSPTA has been integrated into the periodic general health screening program and the KDSQ-P is no longer used; the KDSQ-C is used as a one-step screening tool. The KDSQ-C is a semi-structured questionnaire that includes 15 questions that assess memory impairment, other cognitive impairments including language impairments, and the ability to perform complex tasks in daily life. The KDSQ-C has answer options of ‘no,’ ‘sometimes,’ and ‘often,’ which are scored as 0, 1, 2, respectively. A score of 6 is considered a valid threshold to identify dementia.4

Several other screening tools for dementia have been also used in Korea. The Alzheimer Disease 8 (AD8), developed by Galvin et al.5 in 2005, is useful to distinguish between normal cognitive function (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR]6 of 0), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and very early dementia (CDR of 0.5). It consists of eight questions about changes in memory (answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’), orientation, problem-solving ability, and activities of daily living.5 Although the AD8 was originally developed to be completed by an informant other than the patient, it may also be completed by patients themselves.7,8 A Korean version of the AD8 has also been developed, and a score of 2 was considered a valid threshold to distinguish dementia.9 Using a cut-off score of 2, the AD8 showed a sensitivity of 0.74 and specificity of 0.86 for discriminating normal cognition from MCI and mild dementia.10

The Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire (SMCQ) is a patient-completed screening test for subjective cognitive decline (SCD) developed by Youn et al.11 in 2009. The authors suggest that the SMCQ can discriminate elderly patients with dementia from those without dementia.11 The questionnaire consists of 14 items including subjective reports of general memory and everyday memory. Each question is answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and scored as 1 or 0 points, and a score of 6 is used as the cut-off. The SMCQ has shown a sensitivity of 0.75 and specificity of 0.69.11 The validity of the questionnaire when completed by a caretaker of the patient has not been assessed.

Elderly patients who undergo a national health screening often do this in the absence of a caregiver, which means that the KDSQ-C questionnaire for cognitive dysfunction is often performed by the patient although they have originally been designed to be completed by an informant.4 Therefore, concerns about KDSQ-C questionnaires completed by patients have been raised. The SMCQ, which was originally developed as a self-report questionnaire, has been suggested as an alternative to the KDSQ-C, as has the AD8.

Therefore, the current study aims to examine these concerns by comparing the diagnostic ability of screening questionnaires for cognitive impairment when completed by the patient or an informant during periodic national health screening visits. Specifically, we aimed to evaluate whether the SMCQ or the AD8 is superior to the KDSQ-C and can be used as its replacement.

METHODS

Participants

From August 2017 to April 2018, a total of 420 participants (200 healthy controls, 50 with MCI, 120 with Alzheimer disease [AD], and 50 with other dementias) aged 65 years and above and their informants were recruited from 11 hospitals across Korea, located in Seoul (7), Gyeonggi (3), and Busan (1). These participants were recruited from the department of neurology or the psychiatry outpatient clinic at each hospital or from regional dementia centers in local districts (Mapo-gu, Yangcheon-gu, Gangseo-gu) of Seoul. All participants were examined by an experienced neurologist or psychiatrist and were divided into three subgroups: normal cognition, MCI, and dementia. Participants with normal cognition were defined as cognitively and functionally normal and independent, and fulfilled the health screening exclusion criteria by Christensen et al.12 The normal group had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 1.0 standard deviation (SD) below the norm. MCI was diagnosed based on the criteria of Peterson.13,14 The specific inclusion criteria for MCI were as follows: 1) patient, informant or both reported cognitive decline, 2) cognitive impairment (< 1.5 SDs below age and education-adjusted norms) in ≥ 1 domain (executive function, memory, language, or visuospatial) on standard neuropsychological tests, 3) normal functional activities, and 4) no presence of dementia according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).15

Dementia was categorized as either AD, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). AD was diagnosed based on the probable AD criteria proposed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and AD and Related Disorders Association16 as well as DSM-IV-TR.15 Vascular dementia was diagnosed based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria15 for vascular dementia. FTD was diagnosed based on ‘research criteria for frontotemporal dementia’.17 DLB was diagnosed with the probable DLB criteria proposed in the third report of the DLB consortium.18 Recruitment was limited to patients with very mild to moderate dementia with a CDR of 0.5, 1, or 2.

Individuals with structural or laboratory testing abnormalities that could lead to cognitive decline were excluded. These abnormalities included head injury that resulted in loss of consciousness or cognitive impairment for more than an hour; a history of cerebral hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage; a space-occupying brain lesion; cognitive impairment associated with neurosyphilis; HIV infection, thyroid abnormalities, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency; and history of metabolic encephalopathy. All individuals with Axis I psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, were excluded. Individuals with a physical illness or disorder that could interfere with the clinical study, including hearing or vision loss, aphasia, severe cardiac failure, severe respiratory illnesses, uncontrolled diabetes, malignancy, or hepatic failure or renal disorders with dialysis, were excluded.

Informants were included if they interacted with the participant three or more days per week and spend more than four hours at each interaction. This ensured that informants understood the participant's condition and were able to complete assessments, including questionnaires.

Clinical evaluations

We examined baseline demographic data including age, gender, years of education, medical history, and family history. All participants underwent a Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS)19 test and completed the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale20 to evaluate global cognition and depression, respectively. The KDSQ-C, AD8, and SMCQ were completed separately by participants and their informants to evaluate participants' cognitive function and activities of daily living. Twenty patients with AD, 20 patients with MCI, 40 normal participants, and their informants were asked to complete the same questionnaires one month later to determine their test-retest reliability. The order of administering the three questionnaires was randomly selected. Follow-up questionnaires were administered in the same order as the initial evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as percentages, and continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). To compare groups, Student's t-tests were used for continuous variables with a normal distribution, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables without a normal distribution, and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables. The sensitivity and specificity of each questionnaire and the MMSE-DS for diagnosing dementia were calculated with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Areas under the curve (AUCs) with 95% confidence intervals were generated to assess the diagnostic ability of each screening questionnaire. The AUCs for each instrument were compared using the DeLong method. The AUCs of the questionnaires were considered to be statistically significantly different when the P value was less than 0.008 after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The optimal cut-off score for each questionnaire was selected when Youden's index was maximized by the ROC curve. Test-retest reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and a two-way mixed effects model. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was also calculated. Correlations between participant and informant questionnaire scores were determined with Spearman's correlation coefficients. Fisher's r-to-z transformation analysis was used to assess a statistically significant difference between the two correlation coefficients. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Inst., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics statement

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital (KC17QNDE0093). All participants and informants provided signed informed consent prior to participation in the study.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Of the 420 participants, 233 (55.5%) were women (Table 1). The mean ± SD for participant age at the time of assessment was 75.3 ± 3.9 years (range, 60–93 years), and the mean years of education was 9.1 ± 4.9 years (range, 0–20 years). The study sample consisted of 200 normal participants, 50 participants with MCI, and 170 participants with dementia. In the dementia group, 120 (70.6%) participants were diagnosed with AD, 22 (12.9%) with vascular dementia, 14 (8.2%) with DLB, and 14 (8.2%) with FTD. Eighty-two participants (19.5%) had a family history of dementia: 12.5% in the normal group, 46.0% in the MCI group, and 20.0% in the dementia group. The MCI and dementia groups were significantly more likely to have a family history of dementia than the normal group (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Other characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics of study subjects.

| Characteristics | Total | Normal (A) | MCI (B) | Dementia (C) | P for A vs. B | P for A vs. C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 420 | 200 | 50 | 170 | |||

| Gender, No. (%) | 0.486 | 0.269 | |||||

| Men | 187 (44.5) | 95 (47.5) | 21 (42.0) | 71 (41.8) | |||

| Women | 233 (55.5) | 105 (52.5) | 29 (58.0) | 99 (58.2) | |||

| Age, yr | 0.501 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 75.3 ± 6.0 | 73.7 ± 5.4 | 74.4 ± 5.7 | 77.5 ± 6.2 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 75.0 (60–93) | 74.0 (65–87) | 74.0 (66–86) | 78.0 (60–93) | |||

| Education, yr | 0.121 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.1 ± 4.9 | 9.8 ± 4.3 | 10.8 ± 5.5 | 7.8 ± 5.1 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 9.0 (0.0–20.0) | 9.0 (0.0–19.0) | 12.0 (0.0–18.0) | 6.0 (0.0–20.0) | |||

| Family history of dementia | < 0.001 | 0.050 | |||||

| No | 338 (80.5) | 175 (87.5) | 27 (54.0) | 136 (80.0) | |||

| Yes | 82 (19.5) | 25 (12.5) | 23 (46.0) | 34 (20.0) | |||

| SGDS | 0.075 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 2.5 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–7.0) | 1.0 (0.0–7.0) | 3.0 (0.0–7.0) | 3.0 (0.0–7.0) | |||

| Alcohol | 0.519 | 0.431 | |||||

| No | 346 (82.4) | 162 (81.0) | 43 (86.0) | 141 (82.9) | |||

| Social drinking | 67 (16.0) | 36 (18.0) | 6 (12.0) | 25 (14.7) | |||

| Chronic alcoholics | 7 (1.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (2.4) | |||

| Smoking | 0.051 | 0.698 | |||||

| No | 371 (88.3) | 178 (89.0) | 40 (80.0) | 153 (90.0) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 41 (9.8) | 20 (10.0) | 7 (14.0) | 14 (8.2) | |||

| Smoker | 8 (1.9) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (6.0) | 3 (1.8) | |||

MCI = mild cognitive impairment, SD = standard deviation, IQR = interquartile range, SGDS = short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale.

Comparison of questionnaire scores by group

Table 2 shows the MMSE-DS and questionnaire scores for the normal and cognitive impairment groups evaluated by participants and informants. The highest mean MMSE-DS score was found in the normal group (27.3 ± 1.9 points), followed by the MCI group (24.3 ± 3.2 points), and the dementia group (18.5 ± 5.4 points). The mean ± SD scores for participant-completed KDSQ-C (p-KDSQ-C) were 3.9 ± 3.5 in the normal group, 6.4 ± 5.0 in the MCI group, and 9.3 ± 7.4 in the dementia group. The participant-completed AD8 (p-AD8) scores were 1.0 ± 1.5 in the normal group, 2.5 ± 2.0 points in the MCI group, and 3.7 ± 2.6 points in the dementia group. The participant-completed SMCQ (p-SMCQ) scores were 2.9 ± 2.6 in the normal group, 5.2 ± 3.0 in the MCI group, and 5.9 ± 4.0 in the dementia group. Participant-completed questionnaire scores tended to be lowest in the normal group, followed by the MCI and dementia groups. Informant-completed questionnaire scores also tended to be lowest in the normal group, followed by the MCI and dementia groups. Informant-completed questionnaire scores in the MCI and dementia groups were higher than participant-completed questionnaire scores.

Table 2. Comparison of questionnaire scores by group.

| Variables | Normal (A) (n = 200) | MCI (B) (n = 50) | Dementia (C) (n = 170) | P for A vs. B | P for A vs. C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | |||||||

| MMSE-DS | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 27.3 ± 1.9 | 24.3 ± 3.2 | 18.5 ± 5.4 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 28.0 (26.0–29.0) | 25.0 (23.0–27.0) | 19.0 (15.0–23.0) | ||||

| Range | 21–30 | 10–29 | 3–30 | ||||

| p-KDSQ-C | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 3.5 | 6.4 ± 5.0 | 9.3 ± 7.4 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 5.5 (3.0–9.0) | 7.0 (4.0–12.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–19 | 0–29 | 0–30 | ||||

| p-AD8 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 3.7 ± 2.6 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 4.0 (1.0–6.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 | ||||

| p-SMCQ | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 5.2 ± 3.0 | 5.9 ± 4.0 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) | 5.0 (2.0–9.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–14 | 0–12 | 0–14 | ||||

| Informants | |||||||

| i-KDSQ-C | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 3.5 | 8.6 ± 5.4 | 16.1 ± 8.5 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 7.0 (5.0–12.0) | 15.5 (9.0–24.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–20 | 1–30 | 0–30 | ||||

| i-AD8 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 5.3 ± 2.4 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 6.0 (3.0–7.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 | ||||

| i-SMCQ | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 2.6 | 6.9 ± 3.3 | 9.6 ± 3.8 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | 11.0 (7.0–13.0) | ||||

| Range | 0–13 | 1–14 | 0–14 | ||||

P for differences were determined by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

MCI = mild cognitive impairment, SD = standard deviation, IQR = interquartile range, MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, p-KDSQ-C = participant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, p-AD8 = participant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, p-SMCQ = participant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire, i-KDSQ-C = informant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, i-AD8 = informant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, i-SMCQ = informant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

The sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the MMSE-DS, AD8, KDSQ-C, and SMCQ

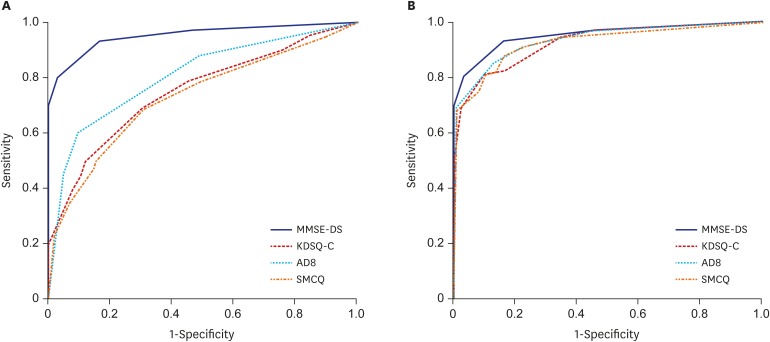

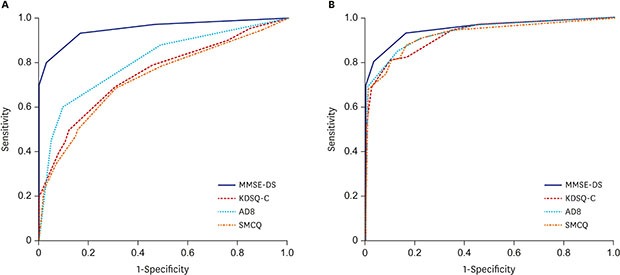

ROC curves were generated to measure the effectiveness of each instrument in classifying the normal vs. dementia groups (Fig. 1). The AUC for MMSE-DS was 0.95. The p-AD8 had an AUC of 0.80, which was higher than that of the p-KDSQ-C (0.75) and p-SMCQ (0.73). For screening of the normal and dementia groups, the p-KDSQ-C had a sensitivity of 0.62 and specificity of 0.77 using a cut-off score of 6. The p-AD8 had a sensitivity of 0.71 and specificity of 0.75 using a cut-off score of 2, and a sensitivity of 0.61 and specificity of 0.89 using an optimal cut-off score of 3. The p-SMCQ had a sensitivity of 0.49 and specificity of 0.84 using a cut-off score of 6 and a sensitivity of 0.67 and specificity of 0.71 using an optimal cut-off score of 4 (Table 3). The AUCs of the informant-completed AD8 (i-AD8), informant-KDSQ-C (i-KDSQ-C), and informant-SMCQ (i-SMCQ) were 0.93, 0.92, and 0.92, respectively. These AUCs were higher than those of the participants. The i-KDSQ-C had the best combination of sensitivity (0.85) and specificity (0.79) using a cut-off score of 6. The i-AD8 had the best combination of sensitivity (0.90) and specificity (0.81) using a cut-off score of 2. The i-SMCQ had the best combination of sensitivity (0.88) and specificity (0.83) using an optimal cut-off score of 5. Both the known and optimal cut-off scores had high sensitivity and specificity (Table 4).

Fig. 1. ROC curve (normal vs. dementia). (A) ROC curve, participants. (B) ROC curve, informants.

ROC = receiver operating characteristic, MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, KDSQ-C = Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, AD8 = Alzheimer Disease 8, SMCQ = Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

Table 3. Sensitivity, specificity of each instrument completed by participants at different cut-off scores for discriminating dementia (normal vs. dementia).

| Cut-off score | Normal (n = 200) | Dementia (n = 170) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE-DS | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | |||||

| ≥ 24 | 184 | 26 | 0.85 (0.78–0.90) | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) | ||

| < 24a | 16 | 144 | ||||

| ≥ 22 | 197 | 45 | 0.74 (0.66–0.80) | 0.99 (0.96–1.00) | ||

| < 22 | 3 | 125 | ||||

| p-KDSQ-C | 0.75 (0.70–0.80) | |||||

| < 6 | 153 | 64 | 0.62 (0.55–0.70) | 0.77 (0.70–0.82) | ||

| ≥ 6a | 47 | 106 | ||||

| p-AD8 | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | |||||

| < 3 | 177 | 67 | 0.61 (0.53–0.68) | 0.89 (0.83–0.93) | ||

| ≥ 3a | 23 | 103 | ||||

| < 2 | 150 | 49 | 0.71 (0.64–0.78) | 0.75 (0.68–0.81) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 50 | 121 | ||||

| p-SMCQ | 0.73 (0.67–0.78) | |||||

| < 4 | 141 | 56 | 0.67 (0.59–0.74) | 0.71 (0.64–0.77) | ||

| ≥ 4a | 59 | 114 | ||||

| < 6 | 168 | 86 | 0.49 (0.42–0.57) | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | ||

| ≥ 6 | 32 | 84 | ||||

AUC = area under the curve, CI= confidence interval, MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, p-KDSQ-C = participant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, p-AD8 = participant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, p-SMCQ = participant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

aOptimal cut-off by Youden's index.

Table 4. Sensitivity, specificity of each instrument completed by informants at different cut-off scores for discriminating dementia (normal vs. dementia).

| Cut-off score | Normal (n = 200) | Dementia (n = 170) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i-KDSQ-C | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | |||||

| < 9 | 185 | 36 | 0.79 (0.72–0.85) | 0.93 (0.88–0.96) | ||

| ≥ 9a | 15 | 134 | ||||

| < 6 | 158 | 26 | 0.85 (0.78–0.90) | 0.79 (0.73–0.84) | ||

| ≥ 6 | 42 | 144 | ||||

| i-AD8 | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | |||||

| < 3 | 177 | 29 | 0.83 (0.76–0.88) | 0.89 (0.83–0.93) | ||

| ≥ 3a | 23 | 141 | ||||

| < 2 | 161 | 17 | 0.90 (0.84–0.94) | 0.81 (0.74–0.86) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 39 | 153 | ||||

| i-SMCQ | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | |||||

| < 5 | 166 | 21 | 0.88 (0.82–0.92) | 0.83 (0.77–0.88) | ||

| ≥ 5a | 34 | 149 | ||||

| < 6 | 173 | 32 | 0.81 (0.74–0.87) | 0.87 (0.81–0.91) | ||

| ≥ 6 | 27 | 138 | ||||

AUC = area under the curve, CI = confidence interval, i-KDSQ-C = informant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, i-AD8 = informant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, i-SMCQ = informant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

aOptimal cut-off by Youden's index.

Comparison of AUCs

For discriminating dementia from the normal group with participant-completed questionnaires, the AUC of the MMSE-DS had significantly better results than did all other questionnaires (P < 0.001). The AUC for the p-AD8 was significantly higher than the AUCs for the p-KDSQ-C and p-SMCQ (P < 0.005). The AUCs for the MMSE-DS and all three questionnaires completed by informants did not differ significantly (P > 0.008) (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of AUCs (normal vs. dementia).

| Instruments | Participant | Informant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | P value | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| MMSE-DS vs. KDSQ-C | −0.205 (−0.256, −0.153) | < 0.001 | −0.029 (−0.060, 0.002) | 0.066 |

| MMSE-DS vs. AD8 | −0.148 (−0.193, −0.103) | < 0.001 | −0.023 (−0.054, 0.008) | 0.142 |

| MMSE-DS vs. SMCQ | −0.226 (−0.279, −0.172) | < 0.001 | −0.030 (−0.063, 0.004) | 0.082 |

| KDSQ-C vs. AD8 | 0.057 (0.019, 0.094) | 0.003 | 0.006 (−0.017, 0.029) | 0.628 |

| KDSQ-C vs. SMCQ | −0.021 (−0.056, 0.014) | 0.240 | −0.001 (−0.023, 0.022) | 0.954 |

| AD8 vs. SMCQ | −0.078 (−0.115, −0.040) | < 0.001 | −0.006 (−0.030, 0.018) | 0.603 |

By DeLong test.

AUC = area under the curve, CI= confidence interval, MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, KDSQ-C = Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, AD8 = Alzheimer Disease 8, SMCQ = Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

Test-retest reliability

At the 1-month follow-up, the ICCs of the participant-completed questionnaires were 0.90, 0.86, and 0.88 for the p-KDSQ-C, p-AD8, and p-SMCQ, respectively. For the informant-completed questionnaires, the ICCs were 0.93, 0.93, and 0.95 for the i-KDSQ-C, i-AD8, and i-SMCQ, respectively. The test-retest reliability of informant-completed questionnaires was higher than those completed by participants (Table 6).

Table 6. Test-retest reliability.

| Variables | Test | Retest | Pearson correlation (95% CI) | ICC (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | ||||||

| KDSQ-C | 0.82 (0.73–0.88) | 0.90 (0.84–0.94) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 6.5 ± 6.0 | 6.8 ± 6.1 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.5 (2–9.5) | 5 (3–9.5) | ||||

| Range | 0–27 | 0–30 | ||||

| AD8 | 0.76 (0.65–0.84) | 0.86 (0.79–0.91) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 2.3 | 2.4 ± 2.4 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0.5–4) | 2 (0–4) | ||||

| Range | 0–8 | 0–8 | ||||

| SMCQ | 0.79 (0.69–0.86) | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 3.4 | 4.7 ± 3.3 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) | ||||

| Range | 0–14 | 0–14 | ||||

| Informant | ||||||

| KDSQ-C | 0.87 (0.81–0.92) | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 8.6 ± 7.3 | 8.8 ± 8.0 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (2.5–13) | 6 (2–13.5) | ||||

| Range | 0–29 | 0–29 | ||||

| AD8 | 0.88 (0.81–0.92) | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 2.8 | 2.7 ± 2.8 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–5) | ||||

| Range | 0–8 | 0–8 | ||||

| SMCQ | 0.91 (0.86–0.94) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.7 ± 4.4 | 5.7 ± 4.7 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (1.5–9.5) | 5 (1–9) | ||||

| Range | 0–13 | 0–14 | ||||

ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient, CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation, IQR = interquartile range, KDSQ-C = Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, AD8 = Alzheimer Disease 8, SMCQ = Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

Correlation of scores between participants and informants

Table 7 shows the correlation between the scores of the MMSE-DS and the other questionnaires using Spearman's correlation. The MMSE-DS was negatively correlated with each questionnaire, and the questionnaires were positively correlated with each other. For participants, the p-KDSQ-C and p-SMCQ had the highest correlation. The p-SMCQ and p-AD8, and p-KDSQ-C and p-AD8 also had high correlations. For informants, the i-KDSQ-C and i-SMCQ had the highest correlation. The i-SMCQ and i-AD8, and i-KDSQ-C and i-AD8 also had a high correlation. Informant- and participant-completed scores were moderately correlated. The MMSE-DS correlated with the p-KDSQ-C, p-AD8, and p-SMCQ to a lesser degree than with the i-KDSQ-C, i-AD8, and i-SMCQ. There were statistically significant differences between the correlation coefficient of the MMSE-DS and the correlation coefficients of each of the three other questionnaires as evaluated by Fisher's r-to-z transformation analyses (Table 8). When the correlations between the MMSE-DS and the three questionnaires were analyzed by subgroup, the correlation coefficients of the normal group and the MCI group were lower compared to the total sample, although not statistically significant. However, the dementia subgroup showed similar results to those of the total sample (data not shown).

Table 7. Correlation of MMSE-DS, KDSQ-C, AD8, and SMCQ between participants and informants.

| Variables | MMSE-DS | p-KDSQ-C | p-AD8 | p-SMCQ | i-KDSQ-C | i-AD8 | i-SMCQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE-DS | 1 | ||||||

| p-KDSQ-C | −0.437 (< 0.001) | 1 | |||||

| p-AD8 | −0.569 (< 0.001) | 0.753 (< 0.001) | 1 | ||||

| p-SMCQ | −0.403 (< 0.001) | 0.804 (< 0.001) | 0.756 (< 0.001) | 1 | |||

| i-KDSQ-C | −0.678 (< 0.001) | 0.522 (< 0.001) | 0.571 (< 0.001) | 0.476 (< 0.001) | 1 | ||

| i-AD8 | −0.691 (< 0.001) | 0.503 (< 0.001) | 0.591 (< 0.001) | 0.474 (< 0.001) | 0.861 (< 0.001) | 1 | |

| i-SMCQ | −0.673 (< 0.001) | 0.525 (< 0.001) | 0.582 (< 0.001) | 0.522 (< 0.001) | 0.890 (< 0.001) | 0.861 (< 0.001) | 1 |

Spearman correlation matrix.

MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, KDSQ-C = Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, p-KDSQ-C = participant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, AD8 = Alzheimer Disease 8, p-AD8 = participant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, SMCQ = Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire, p-SMCQ = participant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire, i-KDSQ-C = informant-completed Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, i-AD8 = informant-completed Alzheimer Disease 8, i-SMCQ = informant-completed Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

Table 8. Results of Fisher's r-to-z transformation for significance of difference between correlation coefficients (n = 420).

| Variables | Correlation coefficients (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Informant | ||

| KDSQ-C with MMSE-DS | −0.437 (−0.511, −0.356) | −0.678 (−0.727, −0.623) | < 0.001 |

| AD8 with MMSE-DS | −0.569 (−0.630, −0.500) | −0.691 (−0.738, −0.637) | 0.003 |

| SMCQ with MMSE-DS | −0.403 (−0.480, −0.319) | −0.673 (−0.723, −0.618) | < 0.001 |

The Fisher's r-to-z transformation (z score) was used to determine significant differences between correlations.

CI = confidence interval, KDSQ-C = Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire-Cognition, MMSE-DS = Mini-Mental State Examination-Dementia Screening, AD8 = Alzheimer Disease 8, SMCQ = Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the diagnostic ability of three questionnaires for dementia evaluation completed by participants and their informants. Regarding informant-completed questionnaires, the AD8, KDSQ-C, and SMCQ showed highly accurate discriminability for dementia, with no difference in discriminability between the three questionnaires. Among participant-completed questionnaires, all three questionnaires showed moderately accurate discriminability for dementia, although they were lower than those of the informant-completed questionnaires. The AD8 had a higher discriminability for dementia than did the KDSQ-C and SMCQ, whose discriminability did not differ from each other. The MMSE-DS correlated negatively with informant- and participant-completed questionnaires, although informant-completed questionnaires showed a higher correlation with the MMSE-DS than participant-completed questionnaires.

The AD8 and KDSQ-C assess not only memory and but also other cognitive functions. The AD8 is based on the CDR, but customized for AD.5 The SMCQ consists of memory-related questions only, and, thus, it may not be able to identify non-AD with non-amnestic symptoms.11 The KDSQ-C uses responses of ‘no’, ‘sometimes’, and ‘often’,4 while the AD8 and SMCQ use ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Three options can provide more accuracy than two options, but can make questions more complex and difficult to answer. Dementia patients, especially, may have difficulty selecting the best answer. Therefore, the AD8 may have better results than the other questionnaires when completed by participants. The present findings are compatible with previous research.7

When comparing questionnaire results between participants and informants, informant-completed questionnaires were more reliable than participant-completed questionnaires. This finding is in line with previous studies, showing that informant-based measurement is more useful in early screening for cognition changes.21,22 However, questionnaires completed by patients with MCI or mild dementia could be used to screen for cognitive decline. The AD8 was superior to the other questionnaires. Considering that most patients attend health check-ups without an informant, the results of this study have important practical implications.

We presented two cut-off scores: the cut-off score from previous studies4,5,11 and the cut-off score we obtained with Youden's index. Using a different cut-off changes questionnaire sensitivity and specificity. We suggest that using cut-off scores with a higher sensitivity is better, because these questionnaires will be used in screening for dementia. The present study confirmed the known cut-off scores as useful in the KDSQ-C and AD8; however, we recommend a new cut-off score for SMCQ.

When the questionnaires were completed by the informant, all three questionnaires had higher scores than when completed by the participants in the MCI and dementia groups. These findings suggest that the MCI and dementia groups could perceive their cognitive decline and evaluate the deficit, but they had less ability to properly evaluate their symptoms and functions than did informants. In the normal group, participants reported higher scores than did informants, probably because some participants with SCD were included in the normal group.

Medical check-ups often depend on a country's social context and cultural background rather than scientific evidence. Korea's population is aging more rapidly than any other country in the world, became an aged society in 2017, and will be a super-aged society by 2026.23 Dementia has rapidly emerged as a major health problem in Korea.1 This context has influenced the Korean national screening program for cognitive impairment to be implemented for patients over 65 years old.

The present study has public health implications. In cases where informant-report is possible, we recommend the KDSQ-C continue to be used in national medical check-ups. The KDSQ-C is not different from AD8 or SMCQ in discriminability for dementia, and consistent data collection by the same questionnaire is important. In cases where informant-report is not possible, either the patient-completed KDSQ-C or AD8 may be used, although their discriminability is lower than those of informant-completed questionnaires. Thus, it is important to obtain information from the informant, even if only by telephone, when the KDSQ-C is used in national medical check-ups.

The present study has several strengths. It is a multicenter study involving sites across the country. Questionnaires were administered to all participants and informants. The diagnosis was based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings and not limited to questionnaire results. Test-retest reliability of questionnaires was assessed for both participants and informants. There are also several limitations of the present study. First, participants were recruited from tertiary university hospitals and dementia centers, and may not represent the general population. Second, the normal group may have included participants with SCD, which might have influenced the results of the present study. Third, as AD accounts for the majority (70.6%) of dementia participants in the present study, we were not able to analyze AD and non-AD dementia, respectively, due to the small sample of non-AD dementia patients. Dominance of AD among dementia might have produced better discriminability of AD8 over KDSQ. Fourth, the small number of MCI cases prevented determining the discriminability of the scale for screening of MCI with validity. Finally, we did not perform imaging studies or comprehensive neuropsychological tests for the normal group.

In conclusion, the KDSQ-C should continue to be used in national medical check-ups in cases with an available informant. When an informant is not available, either the KDSQ-C or AD8 may be used. It is important to obtain information from the informant, even if only by telephone, when the KDSQ-C is used in national medical check-ups.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a 2017 grant from the National Health Insurance Service.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Yang DW.

- Data curation: Kim A, Kim S.

- Formal analysis: Park M, Yim HW.

- Investigation: Kim S, Park KW, Park KH, Youn YC, Lee DW, Lee JY, Lee JH, Jeong JH, Choi SH, Han HJ.

- Methodology: Na S, Yang DW.

- Software: Park M, Yim HW.

- Writing - original draft: Kim A.

- Writing - review & editing: Yang DW.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR) Nationwide Study on the Prevalence of Dementia, 2012. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim TH, Jhoo JH, Park JH, Kim JL, Ryu SH, Moon SW, et al. Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its' short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7(2):102–108. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3.Kim HS, Shin DW, Lee WC, Kim YT, Cho B. National screening program for transitional ages in Korea: a new screening for strengthening primary prevention and follow-up care. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(Suppl):S70–S75. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.S.S70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang DW, Cho BL, Chey JY, Kim SY, Kim BS. The development and validation of Korean Dementia Screening Questionnaire (KDSQ) J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2002;20(2):135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65(4):559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Coats MA, Morris JC. Patient's rating of cognitive ability: using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(5):725–730. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin R, Ng A, Narasimhalu K, Kandiah N. Utility of the AD8 as a self-rating tool for cognitive impairment in an Asian population. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(3):284–288. doi: 10.1177/1533317513481090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryu HJ, Kim HJ, Han SH. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the AD8 informant interview (K-AD8) in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):371–376. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819e6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1942–1948. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youn JC, Kim KW, Lee DY, Jhoo JH, Lee SB, Park JH, et al. Development of the Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(4):310–317. doi: 10.1159/000205512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen KJ, Multhaup KS, Nordstrom S, Voss K. A cognitive battery for dementia: development and measurement characteristics. Psychol Assess. 1991;3(2):168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopman DS, Kramer JH, Boeve BF, Caselli RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Mendez MF, et al. Development of methodology for conducting clinical trials in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 11):2957–2968. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han JW, Kim TH, Jhoo JH, Park JH, Kim JL, Ryu SH, et al. A normative study of the Mini-Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) and its short form (SMMSE-DS) in the Korean elderly. J Korean Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;14(1):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie K, Fuhrer R. A comparative study of the performance of screening tests for senile dementia using receiver operating characteristics analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):627–637. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90135-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morales JM, Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Bermejo F, Del-Ser T. The screening of mild dementia with a shortened Spanish version of the “Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly”. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9(2):105–111. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199509020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics Korea. Population projections for Korea (2015–2065) http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/8/8/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=359108&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt=. Accessed June 29, 2018.