ABSTRACT

Medically led, patient-centred, future care planning for patients predicted to be in their last year of life is possible on the complex care ward of an acute hospital, where patients often wait for social care placement into a nursing home. When the patient lacks the mental capacity to engage in the planning discussions themselves, meetings can take place between the multidisciplinary geriatric team and either those close to the patient or an independent mental capacity advocate. Participants in the meeting should use any existing advance care planning information, as appropriate, to develop ‘best interests advice’ (which can be referred to at a later date when a best interests decision needs to be made for the patient). Any future medical care plan should be reviewed for applicability and validity if the person's condition changes (improves or deteriorates), if the patient or those close to the patient request it, or 6–12 months after the initial plan is made. Education, training and support must be provided to ensure acceptance and understanding of the PEACE (PErsonalised Advisory CarE) process and general end of life care in the community. Specialist palliative care services are often best placed to provide this.

KEYWORDS : End of life care, complex geriatric care, dementia, advance care planning, older persons, personalised care plan, mental capacity act, nursing home

Introduction

This paper presents the development of an innovative end of life care (EoLC)1 project in a district general hospital on the south-east coast of England, which serves one of the most deprived areas and the seventh oldest population in the UK.2 The innovation, known locally as the modified PEACE (PErsonalised Advisory CarE) project, aims to improve the EoLC experiences of patients admitted to a complex care ward (where most patients are frail with multiple comorbidities, usually including advanced dementia) who will be discharged to a nursing home (NH) and are anticipated to be in the last year or less of life.

Advance care planning (ACP) is recommended best practice for patients who are approaching the end of their lives.3,4 Many of the patients admitted to the geriatric complex care ward who are diagnosed with a dwindling EoLC trajectory, however, lack the mental capacity (owing to advanced dementia, for example) to undertake a comprehensive ACP process that addresses their preferences for future medical care. This, together with limited communication between hospitals, primary care and care homes, means that such patients are at increased risk of avoidable, potentially detrimental, future hospital admissions, and poor EoLC care.5,6 (Information from Kings College Hospital audits of nursing home residents hospital admissions and A&E attendances – Hayes 2004, Hayes and Donnelly 2006, and Hayes and Mucci 2007. The PEACE project is an attempt to address these issues through a medically led ‘future care planning’ process, which is facilitated by the expert geriatric multidisciplinary (MDT) team and supported by community palliative care services,7 and which complies with the Mental Capacity Act.8

Solution and methodology

Fundamental to the PEACE project is the development of an individualised EoLC plan. The complex care ward has daily consultant geriatrician input and a full weekly MDT meeting. All patients diagnosed with one or more advanced, progressive, irreversible conditions (such as advanced dementia or advanced Parkinson's disease) who are clinically assessed as likely to be in the last year of life, and who are being discharged to a NH, are identified at the MDT. The patient and/or those close to them (as determined by the patient's mental capacity to participate in future care planning) are offered discussions with the consultant geriatrician or senior member of the geriatric medical team about current and future care. The discussions focus on what best care might look like should predictable deteriorations in existing medical conditions occur after the person leaves hospital. Where there are existing ACPs, these are taken into account; where there is no-one to represent the patient, an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) is appointed. Once agreed, the PEACE plan is uploaded onto the hospital's and paramedic electronic databases. A hard copy accompanies the person to the nursing home, and separate copies are sent to their GP and the hospice-at-home team, providing advice for community healthcare professionals about what actions to take should the person's condition change.

For certain medical events, a PEACE plan may advise hospital readmission for treatment, but in other situations, where readmission would be of no overall medical benefit to the person (for example because they are actively dying from a medically non-reversible deterioration), a plan may suggest care in the NH with support from local palliative care services.

The PEACE document has been modified from that used by Hayes and colleagues.9,10 The modifications include a change of acronym to emphasise that patients with advanced dementia may not be able to participate in ACP, as well as detailed records of any MCA assessment and do not attempt CPR (DNACPR) status discussions. In contrast to other PEACE projects, the local hospice-at-home team contacts the NH to provide support if needed, within a week of discharge. A small grant from NHS innovation paid for a nurse to educate local NHs about the PEACE process and to collect data for the initial pilot project.

Outcomes

Between February 2012 and August 2012, a pilot roll out of the modified PEACE project was undertaken; data were collected until October 2012. The two primary end points collected for patients discharged with a PEACE plan were: (1) the number of readmissions to hospital at three months after discharge and their reasons, and (2) the place and date of any deaths.

In the review period, all patients (or carers as appropriate) identified as eligible for a PEACE discussion accepted the offer of a discussion about future care, and in all cases this led to the development of a PEACE plan. In total, 42 patients were discharged from the complex care ward with PEACE plans. The average (mean) age of patients was 86.7 years with a 68% female and 32% male. Nearly half of the patients (48%) had had one or more admissions to hospital in the preceding year. Only two patients were assessed as having the mental capacity to participate in PEACE planning meetings. The PEACE plans of the remaining 40 patients were developed as the result of ‘best-interest discussions’ between the consultant-led geriatric team and those close to the patient.11

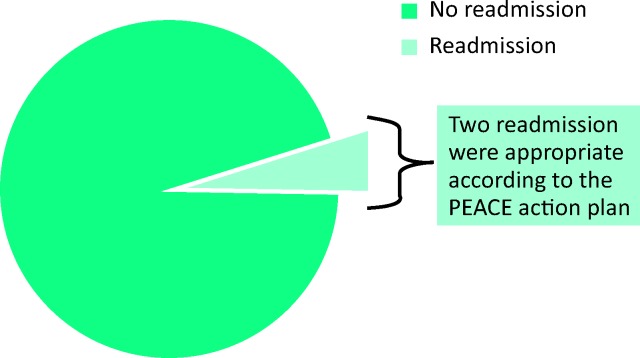

Fig 1 shows that two patients (5%) had readmissions to hospital within three months of discharge. Both admissions were for a trial of antibiotics for severe infection and were consistent with their PEACE plan. There was one additional patient who presented to A&E but was discharged back to their NH without admission.

Fig 1.

Patient readmission during follow-up period. 5% of PEACE patients were readmitted to hospital during the follow-up period. 100% of patients avoided inappropriate hospital admission. PEACE = PEACE (PErsonalised Advisory CarE).

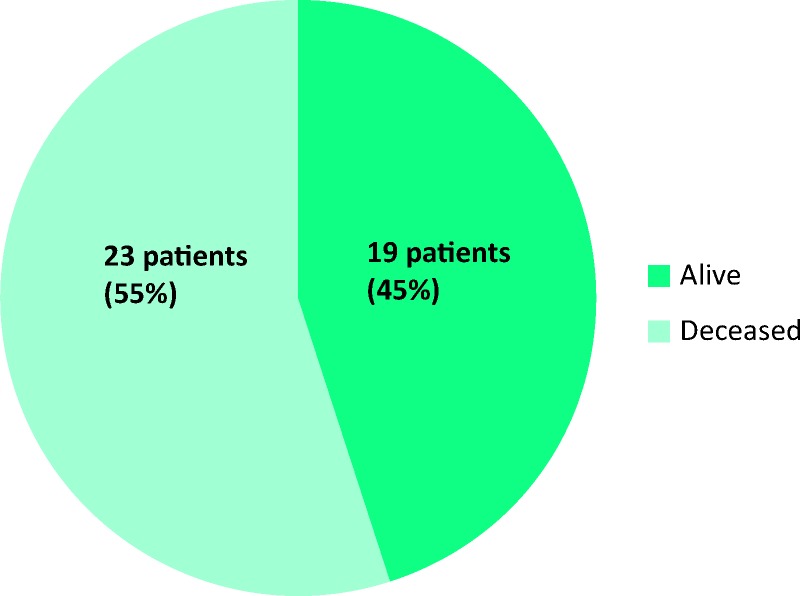

Fig 2 shows that 19 (45%) patients with PEACE plans had died within the review period. The mean time to death was six weeks. All patients died outside of hospital (100%).

Fig 2.

Proportion of PEACE patients alive at follow up. 45% of patents died in their care home within the review period.

In addition to these primary end points, our review looked at completion of PEACE documents and surveyed hospice-at-home and NH staff opinions of the PEACE process. The documentation review revealed a need for improvements in recording of DNACPR discussions and MCA assessments. The survey of staff opinions suggested a need for further education and training in the use of the PEACE documents.

Conclusions and next steps

The PEACE process presented here sets out to address the future needs of patients admitted to a complex care ward who are both resident in or being discharged to a NH and may be in the last months of life. The primary aim is to improve the EoLC experiences of these patients by reducing the number of medically inappropriate and potentially harmful hospital admissions as people approach the end of their life, and in particular to prevent hospital transfer where death is expected in the next few days. In contrast to a strictly defined ACP process in which a patient with capacity expresses their preferences for care and which is used only if they lose the capacity to express these views in the future, PEACE is a medically led and facilitated planning process that can be undertaken with either patients of appropriate mental capacity or with those close to the patient when that person lacks the mental capacity to engage in care planning. Such ‘best interests’ advisory plans strictly follow the code of conduct set out in the MCA.9,12

The original PEACE project was developed at Kings College Hospital, and has greatly influenced the work presented here. Our local PEACE process, however, was a medically (not nursing) led intervention, with EoLC discussions and future medical plans being discussed between the consultant geriatrician (or senior registrar) and the patient and/or those close to them. This process provided medical expertise and reassurance to the patient and/or those close to them when discussing options for possible future medical treatment. No eligible patients in our pilot study or their carers declined discussions about future care or formulation of a PEACE plan. The PEACE documentation was also revised to include, among other things: clarification of advance versus future care planning, a more detailed section on mental capacity assessment; and a section on DNACPR status so that patients or those close to them might not have to repeat the discussion on arrival at the NH. The process was supported through education and direct symptom control advice by the local hospice nursing team, which strengthened the EoLC understandings and confidence within NHs.

The preliminary results suggest that initiating a future care-planning process, such as PEACE, is possible on a geriatric complex care ward within an acute hospital when patients are waiting for NH placement and when the project is supported within the community by palliative care services. The results suggest that inappropriate hospital admissions may be avoided, and that where death is expected, it can be supported in the NH. Our plan is to review the local PEACE process and re-audit the outcomes after one full year of the project (to overcome the limitation of small numbers in this initial review). In this second audit, we will compare the outcomes of patients with a PEACE plan with those of other NH patients approaching the end of life. In addition, we will explore whether an appropriately medically led PEACE process can be initiated in NHS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jane Marqueson (St Michael's Hospice, St Leonards-on-Sea) and Jean Levy (St Christopher's Hospice, London)

References

- 1.Department of Health End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the End of Life. London: DH, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS NHS Clinical Commissioning Group outcome tool, 2013. Available online at http://ccgtools.england.nhs.uk/ccgoutcomes/html/atlas.html [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Physicians Advance care planning: national guideline, concise guidance to good Practice 12. London: RCP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Quality standard for end of life care for adults. Quality standard 13. London: NICE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Care Quality Commission Care update, Issue 2. Newcastle upon Tyne: CQC, March 2013. Available online at www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/cqc_care_update_issue_2.pdf [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alzheimer's Society Dementia 2012: a national challenge. London: March 2012. Available online at www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementia2012 [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mucci E, Benson D. Implementation and audit of the ‘Proactive Elderly persons Advisory CarE’ planning project or modified ‘PEACE project’: a collaboration between geriatric and specialist palliative care services to improve end of life care for elderly patients using a future care planning tool. Abstract FC 9.1 of 13th Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care, Prague, 2013. Available online at www.congressinfo.org/filerun/weblinks/?id=e94550c93cd70fe748e6982b3439ad3b&filename=EAPC-Abstract-Book_FINAL%20Version_small.pdf [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mental Capacity Act , 2005. Available online at www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes N, Kalsi T, Steves C, et al. Advance Care Planning (PEACE) for care home residents in an acute hospital setting: impact on ongoing advance care planning and readmissions. BMJ Support PalliatCare 2011;1:99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleet J, Adegbola B, Richmond N, et al. Advance care planning for carehomes residents in hospital using PEACE (proactive Elderly Advance Care); patient prioritisation and selection, readmission and place of death. Age Ageing 2014, 43; i1– i18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guy's & St Thomas’ Charity Planning future healthcare for people with dementia nearing end of life. Available online at www.gsttcharity.org.uk/projects/eolc.html [Accessed 23 March 2015]. [Google Scholar]