Abstract

Objectives

Health limitations can change older adults’ social relationships and social engagement. Yet, researchers rarely examine how the disability of one’s spouse might affect one’s social relationships, even though such life strains are often experienced as a couple. This study investigates the association between functional and cognitive limitations and social experience in a dyadic context.

Method

We use actor–partner interdependence models to analyze the partner data from 953 heterosexual couples in Wave II (2010–2011) of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project.

Results

One spouse’s functional and cognitive health is associated with the other’s relationship quality, but the pattern varies by gender. Husbands’ functional limitations are associated with lower marital support and higher marital strain in wives, but wives’ functional limitations are related to lower family and friendship strain in husbands. Husbands’ cognitive impairment also predicts higher family and friend support in wives.

Discussion

Findings support a gendered dyadic relationship between health and social life and highlight women’s caregiver role and better connection with family and friends. There are also differences between experiencing cognitive and physical limitations in couples. Finally, mild health impairment sometimes shows stronger effects on social relationships than severe impairment, suggesting adaptation to health transition.

Keywords: Actor-partner interdependence model, Disability, Dementia, Gender, Relationship quality

Cognitive and physical limitations can disrupt older adults’ social activities (Carr & Moorman, 2011; Shaw, Krause, Liang, & Bennett, 2007). They impair interactions with family members and friends and limit community participation (Rosso, Taylor, Tabb, & Michael, 2013), leading to increased loneliness (Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012) and reduced quality of life (Netuveli, Wiggins, Hildon, Montgomery, & Blane, 2006). As the U.S. population ages, a greater proportion of the population is expected to experience functional and cognitive impairment and face challenges in maintaining their social lives (Freedman, 2014; Thies & Bleiler, 2013).

Yet, we know little about how the health and disability of one’s spouse might affect one’s social relationships, even though stressors and life strains are often experienced as a couple or as a family (Carr, Cornman, & Freedman, 2015; Revenson, 2009). When one spouse has health limitations, the other may take on more caregiving and domestic responsibilities, changing the way the healthy spouse experiences the social world (e.g., Korporaal, Broese van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2008; Taylor & Lynch, 2004). Further, this process may be gendered because wives do more care and emotion work than husbands (Li, Mak, & Loke, 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). Women are also more socially connected and report greater support received from family and friends (Turner & Turner, 2013), implying that women may have more to lose in their social life when their spouses face poor health.

We explore this dyadic process using the partner data from Wave II of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). We model the association between functional and cognitive limitations in one partner and reports of social participation and relationship quality of the other. We also examine gender differences in the relationship between health limitations and one’s own and one’s partner’s social experience. This study paints a broader picture of health and social connections at older ages by examining couples rather than just individuals.

Health and Social Relationships in Dyads

We draw on the Interactive Biopsychosocial Model (IBM) to understand how functional and cognitive limitations affect older couples’ social experience (Lindau, Laumann, Levinson, & Waite, 2003). The IBM stresses that an individual’s health is inextricably linked to socially relevant others, including partners, kin, and friends. Spouses are often central to caregiving and maintaining the social life of older adults (Warner & Adams, 2012). Adult children are instrumental when older adults experience severe health deterioration or widowhood (Bookwala, 2009; Leopold, Raab, & Engelhardt, 2014). Friends can also be important sources of health information (e.g., Cornwell & Waite, 2012).

The IBM also emphasizes bidirectional causality and feedback, suggesting that social resources shape health, but health also shapes individuals’ experiences of the social world. Indeed, research documents how marriage produces health at older ages (see Wong & Waite, 2015 for a review). Being married is associated with lower cardiovascular, metabolic, and chronic inflammation risk (McFarland, Hayward, & Brown, 2013; Sbarra, 2009), and better functional health (Moe & Hagen, 2011). A good partnership may promote cognitive health through increasing social interaction (Gow, Corley, Starr, & Deary, 2013; van Gelder et al., 2006) while chronic marital strain may damage cognitive functioning (Xu, Thomas, & Umberson, 2015). Nonspousal social ties can also positively affect health by lowering loneliness and depression (Chen & Feeley, 2014). Overall, quality relationships can benefit health by providing emotional and instrumental support, facilitating health-promoting behaviors, and offering a sense of meaning in life (Berkman & Glass, 2000; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010).

Some studies suggest that social relationships change in response to the onset of health problems (Carr & Moorman, 2011; Shaw et al., 2007). Functional loss or dementia may strain spousal relationships because caregiving for impaired older adults usually falls to spouses, which can distress both the care recipient and the caregiver (Clare et al., 2012). Family relationships and friendships can become less close, as functional limitations predict lower support from nonmarital relationships, and lower frequency of in-person contact with relatives, friends, or neighbors outside the home (Bukov, Maas, & Lampert, 2002; Simonsick, Kasper, & Phillips, 1998; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). Cognitive impairment, a contributor to functional limitations, also predicts lower participation in social and leisure activities (Perlmutter, Bhorade, Gordon, Hollingsworth, & Baum, 2010).

These studies indicate that one’s health shapes his or her interaction with the social world. We theorize that one’s health also shapes a spouse’s social experience. While the IBM suggests on a theoretical level that the couple is an important site for producing health and social well-being, few studies have empirically tested these ideas with data from intimate dyads. The current study addresses this gap by using an actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) to examine whether functional and cognitive limitations in one spouse are related to lower levels of social participation and lower quality of marital and nonmarital relationships in the other (partner effects), over and above any effects of one’s own health limitations on one’s own social relationships (actor effects).

Differences by Health Limitation Severity

The strength of the partner effects may depend on the severity of the partner’s health limitations. Mild functional or cognitive health limitations in one’s spouse may upset or inconvenience the healthy partner and subtly change how the healthy partner interacts with the social world. For instance, when a partner develops difficulties with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)—self-maintenance tasks that enable independent navigation of the environment such as preparing meals (Spector, Katz, Murphy, & Fulton, 1987)—he or she may need more help with routine chores. A spouse consequently may need to be available to help, which reduces his or her availability for other social relationships and activities. Likewise, if a spouse has mild cognitive impairment (MCI)—an early state of cognitive decline characterized by memory loss without major functional impairment (Petersen et al., 1999)—he or she may forget things like medical appointments, which can become an additional responsibility for the healthy spouse. The extra burden of chores such as managing a spouse’s medications or constantly repeating things for a forgetful partner can reduce the healthy spouse’s marital and nonmarital relationship quality because this extra work may leave less energy to satisfyingly engage with spouses, friends, or family members. The healthy spouse’s reduced free time and energy can also restrict engagement in other social activities like club attendance or visiting family and friends (Dunn & Strain, 2001; George & Gwyther, 1986).

A spouse’s severe health limitations can be even more damaging to the healthy partner’s social relationships and his or her social participation. If a partner has difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs)—tasks such as toileting that are essential for self-care (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963)—or dementia—deficits in memory and at least one other cognitive domain that has consequences for functional health (Petersen et al., 1999)—he or she may need full-time caregiving from the healthy spouse, which can bar the healthy partner from participating in social activities. Caring for a disabled spouse may also reduce the healthy spouse’s perceived quality of social relationships because caregiving may physically and emotionally isolate caregivers from family and friends (Evans & Lee, 2014). Further, as cognitive impairment causes people to withdraw from social participation, a healthy spouse could lose the social connections the demented spouse used to maintain for the couple.

Differences by Relationship Type

Older adults’ more central social ties may also have a stronger association with health conditions. Spouses and certain family members (e.g., adult children) are often primary caregivers to the disabled elderly (Bookwala, 2009; Evans & Lee, 2014; Leopold et al., 2014; Warner & Adams, 2012). Therefore, the quality of marital and family relationships may be more strained by spouses’ disability than less-obligatory friendships. For example, although a partner’s dementia can reduce the healthy spouse’s friendship quality by limiting his or her time and energy to invest in friendships, a spouse’s cognitive decline may be especially harmful to spousal relationship quality (Clare et al., 2012; de Jong Gierveld, Broese van Groenou, Hoogendoorn, & Smit, 2009; Evans & Lee, 2014): the demented spouse may become a different person and even become aggressive toward a partner as he or she loses his or her capacity for rationality, reciprocity, and communication (O’Connor, 1994).

Gender Differences

Finally, we expect that women’s social lives will be more responsive than men’s to a partner’s health limitations. In heterosexual marriages, women do more care work than men to improve their spouses’ health (Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Revenson et al., 2016). Women also do more emotion work to maintain marital quality in response to the couple’s health problems (Carr et al., 2015; Thomeer, Reczek, & Umberson, 2015). Perhaps because of this, women tend to feel more emotionally distressed by caregiver burden (Li et al., 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006), and so wives’ experiences of their relationships may be more affected by a partner’s health limitations. Additionally, women on average have larger social networks and find their relationships more satisfying than men do (Fuhrer & Stansfeld, 2002; Turner & Turner, 2013), indicating that women may have more to lose in their social life in the context of spousal disablement.

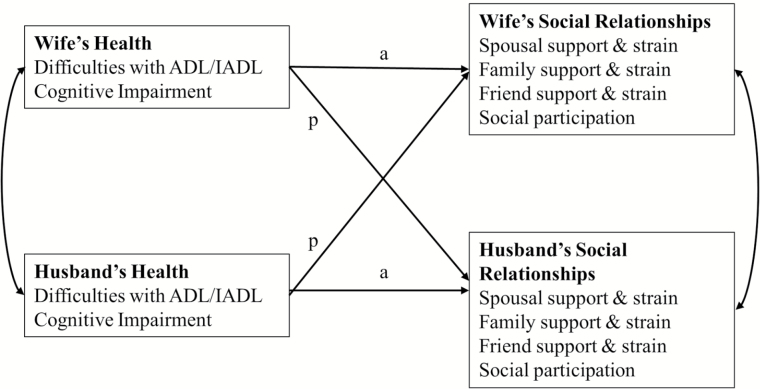

Figure 1 summarizes the association between functional status, cognition, and social relationships in older adult couples. An older adult’s difficulties with ADL/IADL and cognitive impairment predict his or her partner’s quality of spousal/family/friend relationships and social participation (marked p—partner effects) in addition to his or her own social relationships (marked a—actor effects). We account for the possibility that wives’ and husbands’ health conditions and social relationships are correlated due to selection and shared environment—these correlations are estimated but not presented in our results.

Figure 1.

Functional/cognitive limitations and social relationships in older adult couples. Note: (a) denotes actor effects and (p) denotes partner effects.

Methods

Data

The study uses dyadic data from Wave 2 (2010–2011) of NSHAP (Waite et al., 2013). NSHAP started in 2005–2006 (Wave 1) as a nationally representative study of community-dwelling older adults aged 57–85. About 88% of the Wave 1 respondents were re-interviewed 5 years later in Wave 2. Among them, a random subsample of the married and cohabiting respondents was selected for the couple study (i.e., their partners were also contacted by the NSHAP team for an interview). Of 1,107 eligible couples, 955 completed the couple study—supplemental analyses show no systematic differences in the study’s key variables across partnered respondents who did and did not participate in the couple study. More information about the couple sample is available in O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, and Kwok (2014).

To examine gender differences, we exclude two same-sex couples from the sample and analyze 953 heterosexual couples. In analyses of volunteering, organized group meetings, and informal socializing, our sample includes 781,780, and 785 couples, respectively, because these social participation questions were asked in the leave-behind questionnaire (LBQ), which had a lower response rate. Analyses excluding 37 cohabiting couples from the sample produced similar results so we combine married and cohabiting couples to increase sample size.

Variables

We examine four types of social outcomes: marital/cohabiting relationship quality, family relationship quality, friendship quality, and social participation. We measure both positive (support) and negative (strain) aspects of marital, family, and friendship quality. Support from each relationship is assessed with two items: the frequency of being able to (a) open up to and (b) rely on the relationship. Strain is assessed by two additional items: the frequency of (a) demands and (b) criticism from each relationship. All these items are rated 0 = never/hardly ever, 1 = some of the time, and 2 = often. We sum the positive items to represent marital, family, or friend support (α = 0.50, 0.67, and 0.77, respectively). We do the same with the negative items for marital, family, or friend strain (α = 0.59, 0.56, and 0.59, respectively). The resulting support and strain scales range from 0 to 4, where 0 = never/hardly ever for both of the original scale items; 1 = never/hardly ever for one scale item, and some of the time for the other; 2 = some of the time for both scale items, or never/hardy ever for one item, and often for the other; 3 = some of the time for one scale item, and often for the other; and 4 = often for both items.

Social participation is assessed with four indicators: the frequencies of volunteering, attending organized group meetings (e.g., a hobby group), attending religious services, and socializing with friends or relatives. The scale of these variables ranges from 0 = never to 6 = several times a week.

Independent variables include functional and cognitive status. Functional status is a categorical variable indicating whether the respondent had no difficulty with IADLs/ADLs, any difficulty with IADLs but not ADLs, or any difficulty with ADLs (alternate specifications of the IADL/ADL variables in our models [e.g., number of IADLs/ADLs as a continuous measure] show a nonlinear relationship with social life; supplementary analyses are available upon request). Specifically, difficulty with IADLs is measured as reporting difficulty with one or more of the following: preparing meals, taking medications, managing money, shopping for groceries, performing light housework, using a telephone, driving during the day, and driving during the night. Difficulty with ADLs is measured as reporting any difficulty with one or more of the following: walking across a room, walking one block, dressing, bathing/showering, eating, getting in and out of bed, and toileting.

Cognitive status is a categorical variable indicating whether the respondent screened negative for any cognitive impairment, positive for MCI, or positive for dementia. Cognitive status is determined by a survey-adapted version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-SA), an 18-item cognitive screening tool that measures short-term memory; visuospatial abilities; executive functioning; attention, concentration, and working memory; naming; language; and orientation to time and place (Kotwal, Kim, Waite, & Dale, 2016; Kotwal et al., 2015). MoCA-SA scoring ranges from 0 to 30, with scores >22 suggesting no impairment, scores 18–22 (inclusive) suggesting MCI, and scores <18 suggesting dementia for community samples (Kotwal et al., 2016; Luis, Keegan, & Mullan, 2009; Rossetti, Lacritz, Cullum, & Weiner, 2011). Validation for this instrument is available in Kotwal and coworkers (2015) and Shega and coworkers (2014). Robustness checks using different cut-points of the MoCA-SA scores to categorize cognitive status (Freitas, Simões, Alves, & Santana, 2013; Nasreddine et al., 2005) are available upon request.

Covariates include husbands’ and wives’ respective age, education, race/ethnicity, and depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D]) because these factors may be associated with health status and the quantity and quality of social relationships (Cornwell, Laumann, & Schumm, 2008; Gow et al., 2013). Analyses estimating functional status and social relationships also control for MoCA-SA scores to distinguish between physical and cognitive limitations.

Analyses

We analyze the dyadic data using the APIM (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Unlike individual-level analysis, dyadic analysis examines partners’ health status and its association with each person’s social well-being simultaneously. The APIM corrects for potential biases from nonindependence between members of an intimate relationship, a common pitfall in individual-level analyses of marital/cohabiting relationships. The model accounts for these correlations between partners’ characteristics. It is estimated with the “sem” command in Stata 14. We specify the “method(mlmv)” option for full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) to handle item-level missing values. For analyses of volunteering, organized group participation, and socializing with friends and family, we first exclude the cases missing social participation information because they did not return the LBQ, and then use FIML to account for other item-level missing values. All analyses include couples’ sampling weights (adjusted for eligibility and nonresponse) so the results are generalizable to the population of older couples in which at least one partner was aged 62 or older in 2010. We use post hoc Wald tests to identify significant gender differences in the relationships between health status and social well-being and to compare effect sizes across relationship types.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Survey-weighted descriptive statistics in Table 1 show some notable but expected gender differences (all significant at p <.05) in social relationships. On average, wives perceive lower levels of marital support and marital strain than husbands do. Wives also report more support and strain from family and more support from friends compared to husbands. Lastly, wives volunteer, attend organized group meetings, and attend religious services more frequently than husbands do.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Wives (N = 953) | Husbands (N = 953) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/% | % Missing | Mean/% | % Missing | |

| Social relationships (range: 0–4) | ||||

| Marital support* | 3.5 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.4 |

| Marital strain* | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Family support* | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.5 |

| Family strain* | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Friend support* | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.6 |

| Friend strain | 0.1 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 4.5 |

| Social participation (range: 0–6) | ||||

| Volunteering* | 2.4 | 12.1 | 2.0 | 11.3 |

| Attending meetings of organized groups* | 2.8 | 11.9 | 2.4 | 11.6 |

| Attending religious services* | 3.4 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| Socializing with friends or relatives | 4.4 | 11.9 | 4.2 | 11.1 |

| Functional status (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| No limitation | 64.7 | 71.2 | ||

| Any IADL, but no ADL | 20.8 | 16.5 | ||

| Any ADL | 14.5 | 12.3 | ||

| Cognitive status (%)* | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| No impairment | 73.0 | 59.8 | ||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 19.2 | 28.8 | ||

| Dementia | 7.8 | 11.4 | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (range: 36–99)* | 67.6 | 0.0 | 71.1 | 0.0 |

| Education (%)* | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Less than high school | 10.8 | 14.8 | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 24.9 | 23.6 | ||

| Some college/associate degree/vocational certificate | 39.6 | 26.4 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 24.6 | 35.2 | ||

| Race (%) | 0.4 | 0.2 | ||

| White | 87.9 | 87.9 | ||

| Black | 6.4 | 6.4 | ||

| Other | 5.7 | 5.7 | ||

| Hispanic | 7.4 | 0.2 | 7.4 | 0.2 |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D score 0–30)* | 5.16 | 0.0 | 4.15 | 0.0 |

Note: ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

*Significant gender difference at p <.05 based on t tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

The majority of partners (65% of wives and 71% of husbands) report no difficulties with IADLs or ADLs. The majority of the partners also screen normal in the cognitive assessment (73% of wives and 60% of husbands). This pattern of a higher proportion of cognitively healthy women is reversed in the general population that includes both partnered and unpartnered women. Women in marital/cohabiting relationships tend to be younger than their husbands, but women in the general population tend to live longer than men, and age is a dominant factor in cognitive functioning (Salthouse, 2012; Steinerman, Hall, Sliwinski, & Lipton, 2010).

Functional Limitations and Social Relationships

Couples’ functional limitations are associated with marital, family relationship, and friendship quality. However, the association varies by gender and by relationship type. Model 1 in Table 2 shows that wives report lower spousal support and higher spousal strain when their husbands have severe functional limitations (ADLs). For example, compared to wives whose husbands have no functional limitations, wives with husbands who have any difficulty with ADLs report marital support scores that are 0.21 points lower—nearly a third of a standard deviation lower—on the 4-point scale. In contrast, husbands’ perceived marital quality is unrelated to their wives’ experience of functional limitations (gender difference for support: χ2(1) = 2.94, p < .10; and strain: χ2(1) = 5.27, p < .05). This gendered pattern is consistent with the notion that wives tend to do more health-promoting care work in a marriage (Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Revenson et al., 2016): when husbands have functional limitations, wives may worry more and monitor their spouses’ health behaviors more closely, thus eroding women’s perception of the marriage. When wives experience health issues, however, they may continue to provide care to husbands, and so husbands with sick wives do not perceived worse marital quality.

Table 2.

Actor and Partner Effects of Functional Limitations on Social Relationships

| Wives’ report | Husbands’ report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: marriage quality (N = 953 couples) | Support | Strain | Support | Strain |

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.07 |

| Any ADL | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.16 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.16 |

| Any ADL | −0.21* | 0.30* | 0.13 | 0.20 |

| Model 2: family quality (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.06 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.12* |

| Any ADL | −0.03 | 0.14 | 0.25 | −0.06 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.21* |

| Any ADL | 0.19 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.08 |

| Model 3: friendship quality (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.21 | −0.06* | −0.15 | −0.08* |

| Any ADL | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.37 | −0.06 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13* |

| Any ADL | −0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 |

| Model 4: volunteering (N = 781 couples) | Frequency of social participation | |||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.11 | −0.11 | ||

| Any ADL | 0.61 | −0.39 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.20 | 0.13 | ||

| Any ADL | 0.24 | 0.40 | ||

| Model 5: attending meetings of organized groups (N = 780 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.10 | −0.11 | ||

| Any ADL | 0.33 | −0.20 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.37 | −0.23 | ||

| Any ADL | −0.16 | −0.22 | ||

| Model 6: religious attendance (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | −0.20 | −0.37 | ||

| Any ADL | −0.54 | −0.39 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.11 | 0.10 | ||

| Any ADL | 0.31 | 0.30 | ||

| Model 7: socializing with friends/relatives (N = 785 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.11 | 0.14 | ||

| Any ADL | 0.13 | −0.04 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Any IADL, no ADL | 0.11 | 0.01 | ||

| Any ADL | −0.01 | 0.16 | ||

Note: The reference category in all cases is “no functional limitations.” Boldfaced values are partner effects, and values in regular type are actor effects. All analyses are adjusted for wives’ and husbands’ respective age, education, race/ethnicity, cognitive health, and depression. ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living.

*p < .05.

Moreover, Models 2 and 3 suggest that husbands report less strain from family and friends when their wives have IADLs. However, wives do not “benefit” from family or friends in a similar way when their husbands experience functional limitations (gender difference for family: χ2(1) = 4.82; and friends: χ2(1) = 6.19; both ps < .05). This gender difference further supports the notion that husbands are less expected to fulfill caregiving responsibilities than wives: family members and friends may lower their demands and criticisms of men whose wives have difficulty with IADLs, but they may not do the same for women whose husbands have difficulties with IADLs. We also find that husbands report more strain from family and friends than wives do (gender difference for family: χ2(1) = 8.91; and friends: χ2(1) = 10.69; both ps < .01) when they experience their own mild functional limitations (IADLs). Perhaps men are not socialized to adopt health-promoting behaviors (Courtenay, 2000), so they see their family’s and friends’ concerns about their health as annoying or bothersome.

There is some evidence that women’s martial quality may be more compromised in the face of their husbands’ functional limitations than their family relationship and friendship quality. The negative association between husbands’ ADLs and wives’ marital support is larger than its negative association with wives’ family support (χ2(1) = 9.39, p < .01). The positive relationship between husbands’ ADLs and wives’ marital strain is also larger than its relationships with wives’ family and friend strain (χ2(1) = 4.01 for family and χ2(1) = 4.67 for friends, ps < .05).

Finally, functional health is not significantly associated with the frequencies of attending social activities for either wives or husbands (Models 4–7).

Cognitive Limitations and Social Relationships

We find a different pattern in the association between couples’ cognitive status and social relationships. Table 3 shows that wives’ and husbands’ cognitive limitations neither predict their own nor their partners’ perceived marital quality (Model 1). However, wives whose husbands screen positive for MCI report more family and friend support (Models 2 and 3). Compared to wives whose husbands have no cognitive impairment, wives whose husbands have MCI score 0.21 and 0.28 points higher on the 4-point family and friend support scales, respectively (nearly a third of a standard deviation higher). Contrastingly, husbands’ quality of nonspousal relationships appears unrelated to their partners’ cognitive limitations (although gender difference tests are not statistically significant). This pattern may arise because women tend to have closer nonmarital relationships than men: wives may be better at mobilizing nonspousal support in response to their husbands’ cognitive decline.

Table 3.

Actor and Partner Effects of Cognitive Impairment on Social Relationships

| Wives’ report | Husbands’ report | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: marriage quality (N = 953 couples) | Support | Strain | Support | Strain |

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 0.13 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| Dementia | 0.19 | −0.10 | −0.12 | −0.20 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| Dementia | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.19 |

| Model 2: family quality (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Dementia | −0.13 | −0.27* | 0.18 | 0.07 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 0.21* | 0.02 | −0.17 | −0.07 |

| Dementia | 0.17 | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.05 |

| Model 3: friendship quality (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Dementia | −0.42 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 0.28* | 0.01 | 0.16 | −0.09* |

| Dementia | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.12 |

| Model 4: volunteering (N = 781 couples) | Frequency of social participation | |||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.62** | −0.08 | ||

| Dementia | −0.45 | 0.37 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 0.04 | −0.42 | ||

| Dementia | 0.03 | −0.63* | ||

| Model 5: attending meetings of organized groups (N = 780 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.41 | 0.02 | ||

| Dementia | −0.48 | −0.14 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.11 | −0.54 | ||

| Dementia | −0.12 | −0.88** | ||

| Model 6: religious attendance (N = 953 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.03 | 0.08 | ||

| Dementia | −0.02 | −0.15 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.11 | 0.02 | ||

| Dementia | 0.34 | 0.33 | ||

| Model 7: socializing with friends/relatives (N = 785 couples) | ||||

| Wives | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | −0.22 | −0.07 | ||

| Dementia | −0.20 | −0.43 | ||

| Husbands | ||||

| Mild cognitive impairment | 0.00 | 0.20 | ||

| Dementia | 0.01 | 0.26 | ||

Note: The reference category in all cases is “no cognitive impairment.” Boldfaced values are partner effects, and values in regular type are actor effects. All analyses are adjusted for wives’ and husbands’ respective age, education, race/ethnicity, and depression.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

We find two actor effects: wives with dementia perceive lower family strain and husbands with MCI perceive lower friend strain. These findings suggest that family members and friends may consciously reduce their demands or criticisms of those with cognitive impairment. However, it is also possible that cognitive impairment damages one’s ability to correctly evaluate social experiences.

Tests comparing coefficients for cognitive status across marital, family, and friend relationship models show some significant differences. The positive relationship between husbands’ MCI and wives’ family and friendship quality is larger than its association with wives’ marital quality (χ2(1) = 6.81 for family and χ2(1) = 7.74 for friends, ps < .05). This finding is inconsistent with our hypothesis that marital quality would be most strongly linked to a partner’s health status.

Lastly, we find that cognitive status predicts lower participation in some social activities. Model 4 shows that both wives and husbands volunteer less often (about third of a standard deviation below their respective means) when they themselves have MCI (wives) or dementia (husbands). Husbands also attend meetings of organized groups less frequently when they experience dementia (Model 5).

Discussion

Although health problems are often experienced as a couple or as a family, the majority of population-level research on health focuses on the individual. Following the IBM and using a dyadic approach, this study examines how one spouse’s functional and cognitive limitations are related to the other’s social life. Our findings demonstrate the interdependence of older partners in the face of illness. Results also highlight that gender shapes the dyadic link between illness and social relationships, and that physical versus cognitive and mild versus severe forms of limitations may have different implications for couples’ social experience.

We find that the association between one spouse’s functional limitations and the other’s social relationships is gendered, perhaps because men and women play different roles in heterosexual relationships, and engage with the broader social world differently. Men’s severe functional limitations are associated with less marital support and more marital strain for women, reflecting wives’ greater likelihood to care for spouses (Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Revenson et al., 2016) and greater likelihood to be emotionally distressed by caregiving (Li et al., 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2006). Women’s mild functional limitations, on the other hand, predict less strain in nonmarital relationships for men, perhaps because family and friends demonstrate more understanding toward men with functionally impaired wives by lowering their demands and criticism (but not necessarily by offering more support).

There are also gender differences in actor effects. Men, but not women, perceive higher family and friend strains when they have functional limitations (IADLs). Previous studies suggest that men may perceive benevolent health interventions by significant others as demands, criticisms, or “nagging” (Birditt, Newton, & Hope, 2014; Warner & Adams, 2016).

Gender differences in the experience of cognitive impairment are consistent with the notion that women are better connected and receive more nonmarital support than men (Turner & Turner, 2013). Husbands’ MCI predicts more friend and family support in wives, but wives’ cognitive status does not predict husbands’ nonmarital relationships. This finding suggests that wives may draw on social resources by actively mobilizing family and friends when their husbands have cognitive limitations. Conversely, husbands, who are not as close to family members and friends as wives are, might not look for support from relatives and friends when wives have cognitive impairment.

We also show that the link between health and relationship quality differs by relationship type. Husbands’ functional limitations are more strongly associated with wives’ marital quality than with wives’ family or friendship quality. This supports the notion that spouses play the most central role in older adults’ social life (Warner & Adams, 2012). However, we find a different pattern for cognitive impairment, which predicts quality of nonmarital relationships, but not marital quality. This result is inconsistent with previous findings (many of which are based on small samples) that a partner’s dementia may be especially harmful to spousal relationship quality (Clare et al., 2012; Evans & Lee, 2014). We recognize that living with and caring for a demented partner can be highly distressing, but we also contend that people lower their expectations of their spouses when spouses lose their capacity for rationality, reciprocity, and communication during the process of cognitive decline. This may lead to ambivalent feelings (e.g., frustrated, but sympathetic and tolerant) toward the cognitively-impaired spouse, which is reflected in the statistically insignificant association between individuals’ marital quality and their spouses’ cognitive status.

Other evidence suggests differences between experiencing physical and cognitive limitations. Cognitive impairment predicts one’s own lower participation in volunteer work and organized meetings, but functional limitations (controlling for cognitive impairment) does not. This finding indicates that these social activities may be too mentally demanding (e.g., requiring more language skills and collaboration on tasks) for those facing cognitive limitations. Moreover, those with only physical limitations may use assistive devices that allow them to continue engaging in social activities, but there are fewer resources that allow those with cognitive impairment to maintain their social participation.

Further examination of the relationship between functional and cognitive limitations and social relationships reveal other notable patterns. Somewhat unexpectedly, difficulty with IADLs and MCI sometimes show more significant associations with relationship quality and social participation than difficulty with ADLs or dementia. For example, wives’ difficulties with IADLs, but not ADLs, are associated with husbands’ reports of lower strain from family and friends. Also, husbands’ MCI, but not dementia, is related to wives’ reports of higher support from family and friends. Additionally, husbands’ difficulties with IADLs, but not ADLs, are related to their own reports of higher strain from family and friends. Perhaps the initial transition to coping with a partner’s or one’s own health limitations elicits more instrumental or emotional support from close social ties (as discussed earlier, men may perceive this support as “strain”). However, in the long run when health problems persist and deteriorate, support from these ties may be partly replaced by other sources of assistance (e.g., professional help), and individuals may also overcome negative emotions resulting from their own physical challenges (Baltes & Smith, 2003).

This study faces a few limitations. First, we cannot determine the causal direction between health and social relationships with cross-sectional data. As many studies have indicated, quality marriages promote health through resource sharing, mutual support, behavioral change and control, and a sense of belonging (House et al., 1988; Umberson et al., 2010). Yet, in a dyadic context, health limitations may have a stronger impact on some of the partner’s social relationships than vice versa. For example, it is more likely that husbands’ functional limitations affect wives’ friendship quality than that wives’ friendship quality affects husbands’ functional status. Future research should use dyadic panel data to assess both directions of causality.

Second, our sample is affected by attrition and missing data. Because we use NSHAP Wave 2 data, sample attrition between Wave 1 and Wave 2 due to mortality, incapacity, or relocation to care facilities may lead to more conservative results. Couples interviewed may be particularly successful at coping with functional and cognitive limitations. Therefore, the effects of health deterioration on social relationships are likely underestimated. We are also missing data from 12% of couples in the analyses of social participation because those questions are asked in the LBQ rather than in the in-person interview. LBQ return rates differed by physical and mental health status, with higher rates of returning the LBQ among healthier respondents (Hawkley, Kocherginsky, Wong, Kim, & Cagney, 2014). This pattern suggests that our social participation results might be even more conservative.

Lastly, some of our relationship quality variables have low reliability coefficients, in part because we use only two items to measure relationship support and strain. Yet, supplemental factor analyses show the variables consistently load together, so we trust the items adequately measure support and strain.

Despite these limitations, our findings showcase that older adults’ health and social lives are inextricably linked to their significant others’ health and social lives. While the literature has confirmed that maintaining quality social relationships is crucial to an individual’s well-being, our study suggests that having a sick or disabled spouse makes it difficult to do so. Future research will benefit from exploring the intergenerational context of elder disablement, a topic particularly relevant for unmarried older population.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging grants R01 AG021487, R37 AG030481, R01 AG033903, R01 AG043538, R01 AG048511, and T32 AG000243.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Linda Waite and Ashwin Kotwal for providing feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. J. S. Wong wrote the paper and performed robustness checks. N. Hsieh performed the statistical analyses and revised the manuscript.

References

- Baltes P. B., & Smith J (2003). New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology, 49, 123–135. doi:10.1159/000067946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F., & Glass T (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Berkman L., Kawachi I. (Eds.), Social Epidemiology (137–173). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K. S. Newton N., & Hope S (2014). Implications of marital/partner relationship quality and perceived stress for blood pressure among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 188–198. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2009). The impact of parent care on marital quality and well-being in adult daughters and sons. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64, 339–347. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukov A. Maas I., & Lampert T (2002). Social participation in very old age: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, P510–P517. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.6.P510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Cornman J. C., & Freedman V. A (2015). Marital quality and negative experienced well-being: An assessment of actor and partner effects among older married persons. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 177–187. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., & Moorman S. M (2011). Social relations and aging. In A. R., Settersten, L. J., Angel (Eds.), Handbook of sociology of aging (pp. 145–160). New York: Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., & Feeley T. H (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 141–161. doi:10.1177/0265407513488728 [Google Scholar]

- Clare L. Nelis S. M. Whitaker C. J. Martyr A. Markova I. S. Roth I., … Morris R. G (2012). Marital relationship quality in early-stage dementia: Perspectives from people with dementia and their spouses. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 26, 148–158. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318221ba23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B. Laumann E. O., & Schumm L. P (2008). The social connectedness of older adults: A national profile. American Sociological Review, 73, 185–203. doi:10.1177/000312240807300201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell E. Y., Waite L. J. (2012). Social network resources and management of hypertension. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 215–231. doi:10.1177/0022146512446832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50, 1385–1401. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J. Broese van Groenou M. Hoogendoorn A. W., & Smit J. H (2009). Quality of marriages in later life and emotional and social loneliness. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B, 497–506. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn N. J., & Strain L. A (2001). Caregivers at risk? Changes in leisure participation. Journal of Leisure Research, 33, 32–55. doi:https://search.proquest.com/docview/201221814?accountid=14657 [Google Scholar]

- Evans D., & Lee E (2014). Impact of dementia on marriage: A qualitative systematic review. Dementia, 13, 330–349. doi:10.1177/1471301212473882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman V. A. (2014). Research gaps in the demography of aging with disability. Disability and Health Journal, 7, S60–S63. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas S. Simões M. R. Alves L., & Santana I (2013). Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 27, 37–43. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bfe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer R., & Stansfeld S. A (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from “close persons”. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 811–825. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L. K., & Gwyther L. P (1986). Caregiver well-being: A multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. The Gerontologist, 26, 253–259. doi:10.1093/geront/26.3.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A. J. Corley J. Starr J. M., & Deary I. J (2013). Which social network or support factors are associated with cognitive abilities in old age?Gerontology, 59, 454–463. doi:10.1159/000351265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C. Kocherginsky M. Wong J. Kim J., & Cagney K. A (2014). Missing data in Wave 2 of NSHAP: Prevalence, predictors, and recommended treatment. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69 (Suppl_2): S38–S50. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S. Landis K. R., & Umberson D (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545. doi:10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. Ford A. B. Moskowitz R. W. Jackson B. A., & Jaffe M. W (1963). Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 185, 914–919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A. Kashy D. A., & Cook W. L (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M. Broese van Groenou M. I., & van Tilburg T. G (2008). Effects of own and spousal disability on loneliness among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 306–325. doi:10.1177/0898264308315431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal A. A. Kim J. Waite L., & Dale W (2016). Social function and cognitive status: Results from a US Nationally Representative Survey of Older Adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 854–862. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3696-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal A. A. Schumm P. Kern D. W. McClintock M. K. Waite L. J. Shega J. W., … Dale W (2015). Evaluation of a brief survey instrument for assessing subtle differences in cognitive function among older adults. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 29, 317–324. doi:10.1097/WAD.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold T. Raab M., & Engelhardt H (2014). The transition to parent care: Costs, commitments, and caregiver selection among children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 300–318. doi:10.1111/jomf.12099 [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. P. Mak Y. W., & Loke A. Y (2013). Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: A literature review. International Nursing Review, 60, 178–187. doi:10.1111/inr.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T. Laumann E. O. Levinson W., & Waite L. J (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: The interactive biopyschosocial model. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46, S74–S86. doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis C. A. Keegan A. P., & Mullan M (2009). Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24, 197–201. doi:10.1002/gps.2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland M. J. Hayward M. D., & Brown D (2013). I’ve got you under my skin: Marital biography and biological risk. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75, 363–380. doi:10.1111/jomf.12015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe J. O., & Hagen T. P (2011). Trends and variation in mild disability and functional limitations among older adults in Norway, 1986–2008. European Journal of Ageing, 8, 49–61. doi:10.1007/s10433-011-0179-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Z. S. Phillips N. A. Bédirian V. Charbonneau S. Whitehead V. Collin I., … Chertkow H (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53, 695–699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netuveli G. Wiggins R. D. Hildon Z. Montgomery S. M., & Blane D (2006). Quality of life at older ages: Evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (Wave 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 357–363. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.040071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor D. (1994). The impact of dementia. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 20, 113–128. doi:10.1300/J083v20n03_05 [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C. English N. Pedlow S., & Kwok P. K (2014). Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S15–S26. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter M. S. Bhorade A. Gordon M. Hollingsworth H. H., & Baum M. C (2010). Cognitive, visual, auditory, and emotional factors that affect participation in older adults. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64, 570–579. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C. Smith G. E. Waring S. C. Ivnik R. J. Tangalos E. G., & Kokmen E (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology, 56, 303–308. doi:10.1001/archneur.56.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, P33–P45. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C., & Umberson D (2012). Gender, health behavior, and intimate relationships: Lesbian, gay, and straight contexts. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1783–1790. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson T. A. (2009). Scenes from a marriage: Examining support, coping, and gender within the context of chronic illness. In: Suls J., & Wallston K. A., editors. Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness (pp. 530–559). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Revenson T. A. Griva K. Luszczynska A. Morrison V. Panagopoulou E. Vilchinsky N., & Hagedoorn M (2016). Gender and caregiving: The costs of caregiving for women. In: Revenson T. Griva K. Luszczynska A. Morrison V. Panagopoulou E. Vilchinsky N., & Hagedoorn N.. Caregiving in the illness context (pp. 48–63). London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti H. C. Lacritz L. H. Cullum C. M., & Weiner M. F (2011). Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology, 77, 1272–1275. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318230208a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso A. L. Taylor J. A. Tabb L. P., & Michael Y. L (2013). Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 617–637. doi:10.1177/0898264313482489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. (2012). Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 201–226. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D. A. (2009). Marriage protects men from clinically meaningful elevations in C-reactive protein: Results from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 828–835. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b4c4f2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B. A. Krause N. Liang J., & Bennett J (2007). Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, S90–S99. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.S90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shega J. W. Sunkara P. D. Kotwal A. Kern D. W. Henning S. L. McClintock M. K., … Dale W (2014). Measuring cognition: The Chicago Cognitive Function Measure in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project, Wave 2. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S166–S176. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsick E. M. Kasper J. D., & Phillips C. L (1998). Physical disability and social interaction: Factors associated with low social contact and home confinement in disabled older women (The Women’s Health and Aging Study). The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53B, S209–217. doi:10.1093/geronb/53B.4.S209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector W. D. Katz S. Murphy J. B., & Fulton J. P (1987). The Portugal conference: Measuring quality of life and functional status in clinical and epidemiologic research. The hierarchical relationship between activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 481–489. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90004-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinerman J. R. Hall C. B. Sliwinski M. J., & Lipton R. B (2010). Modeling cognitive trajectories within longitudinal studies: A focus on older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(Suppl 2), S313–S318. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02982.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. G., & Lynch S. M (2004). Trajectories of impairment, social support, and depressive symptoms in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S238–S246. doi:10.1093/geronb/59.4.S238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies W., & Bleiler L (2013). 2013 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 9, 208–245. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer M. B. Reczek C., & Umberson D (2015). Gendered emotion work around physical health problems in mid- and later-life marriages. Journal of Aging Studies, 32, 12–22. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. B., & Turner R. J (2013). Social relations, social integration, and social support. In C. S. Aneshensel J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 341–356). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Crosnoe R., & Reczek C (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder B. M. Tijhuis M. Kalmijn S. Giampaoli S. Nissinen A., & Kromhout D (2006). Marital status and living situation during a 5-year period are associated with a subsequent 10-year cognitive decline in older men: The FINE Study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, P213–P219. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.4.P213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J. Cagney K. Cornwell B. Dale W. Huang E. Laumann E. O., … Schumm L. P (2013). National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 2 and partner data collection. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., & Adams S. A (2012). Widening the social context of disablement among married older adults: Considering the role of nonmarital relationships for loneliness. Social Science Research, 41, 1529–1545. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., & Adams S. A (2016). Physical disability and increased loneliness among married older adults. Society and Mental Health, 6, 106–128. doi:10.1177/2156869315616257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., & Kelley-Moore J (2012). The social context of disablement among older adults: Does marital quality matter for loneliness?Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 50–66. doi:10.1177/0022146512439540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J. S., & Waite L. J (2015). Marriage, social networks, and health at older ages. Journal of Population Ageing, 8, 7–25. doi:10.1007/s12062-014-9110-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M. Thomas P. A., & Umberson D (2015). Marital quality and cognitive limitations in late life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 165–176. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]