Abstract

Background

Inequality in the access to health services is a major cause of health problemsamong children under five old. The aim of this analysis is to measure the inequality among children under-5 years in relation to main health indicators in Uganda.

Methods

Main child health indicators data in Uganda were obtained from WHO inequity data set for the years 1995, 2000, 2001 and 2011. Indicators such as under-5 years mortality rate, underweight prevalence and full vaccination converge and child with infection access to health facilities were included in the analysis. For simple indicators, inequality difference was calculated, and relative concentration index for complex order indicators was used. Four different inequality dimensions were used to work as stratifies for these indicators.

Results

Inequality regarding child health indicators was observed in different dimensions. It was clear that inequality among people living in rural areas were more than urban areas. Femaleshad high inequality than males. Poor and uneducated people are more likely to have inequality than rich and educated people.

Conclusion

Great effort should be made to decrease inequality among children less than five years through access to health services for all groups in different areas.

Keywords: Equality analysis, children, Uganda, imaging

Introduction

Most of least and middle income countries continue to suffer from fragile health system, undeveloped capacity and limited financial resources. Still, there is a big gap between what has been achieved and what was supposed to be attained . This gap is clear when we look at the level of its distribution distribution among different groups of people in one country such asthoseliving in rural or urban areas.

Not achieving millennium development goals (MDGs in the majority of developing countries because of that poor peopledon't have access to health services. It is unfair just because children living in rural areas have no access to the primary health care services. It is also unacceptable that child die because he was born in a poor family living in a poor country (1). The African region of the World Health Organization was behind the most MDGs indicators particurally in child health. Access to health services in African region is among the lowest in the world (2). In order to improve child health, the health system should be strengthened through long lasting investment in health such as staff training and building health facilities particularly in remote poor areas.

Therefore, the issue of inequality between people living in one county, or among different countries is of fundamental importance. Inequality in health has a great effect and may lead to poor health outcome in most of the other dimension of well being. Thus, talking health inequity in health has great implications in achieving health for all population and countries. Equity in health should assure that there is equality in the health outcomes among groups or individuals who are similar in many dimensions.

Uganda is classified as a least developing country located in the Middle East of Africa surrounded by South Sudan, Democratic republic of Congo, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda. The total population of Uganda is 40 million and it occupies 36,040 Km2 of land. The percentage of the population under 15 years represents 49.9% of the total population, and the percentage of males and females is almost the same. In Uganda, the population density is 164.6 per Km2, and life expectancy at birth is 53.2 years (3). The GDP per capita is 739 USD (annual 1769 USD), and the total national debt per capita is 626 USD.

Uganda is among countries that have a high rate of under-5 mortality, 55 deaths per 1000 live births. Moreover, the incidence of tuberculosis is very high which is 160 cases per 100,000. Prevalence of under-5 children with underweight is 13.8, sleeping in insecticides treated nets (ITNs) 74.3% while the rate of under-5 children with diarrhea receiving oral rehydration is 48.2 (4).

To fill gap in the health services still needs more efforts form health authorities. However, the question raised here is that whether all these indicators are similar for poor and rich people, educated and non-educated people, or if they are relate to the economic status of all groups of people. To answer these questions, we should look at the health inequity distribution among all these groups. This study assessed the children health equality by looking at these indicators and their distribution using the World Health Organization's Health Equity Assessment Toolkits (Heat) (5).

Method

Data on under-5 mortality rate, BCG vaccination coverage, prevalence ofunder-5 years children with underweight, sleeping in insecticides treated nets (ITNs) and rate ofunder-5 years children with diarrhea receiving oral rehydration in Uganda were obtained from WHO-HEAT the Built-in Database of 1995 –2011.

The main inequality dimensions used to assess the inequity include economic status, parent education level, sex and area of residence. To make pair-wise comparison for simple measures such as absolute inequality to reflect the difference between two subgroups such as male and female. For the complex measure of inequality, we used two different approaches for sub-groups with natural order (such as sex and urban-rural setting), and sub-groups without natural order. Slope index of inequality (assessment of the absolute difference) of inequality was used to calculate the absolute difference for naturally ordered sub-groups such as the level of education. This index allows for the prediction values for the health indicator taking in to consideration the highest and the lowest levels of this indicator.

Results

Under-5 years mortality rate was 162 per 1000 malechildren, and 152 for female in 1995. This number increased in 2000 to 164 male children, but it decreased among female children to 149. In 2006, under-5 mortality rate decreased to 130 deaths per 1000 live birthsfor female children, and 160 for male children respectively. However, in the year 2011, it became less 100 among female children and 117 among male children. Under-5 mortality rate in rural areas was 161.7, 163.3, 159 and 113.5 per 1000 live births in 1995, 2000, 2006 and 2011 respectively. Under-5 mortality rate was high among the poor compare to the rich in 1995, 2000, 2006 and 2011. Also, people with no education had high rate of under-5 mortality in the same period; the difference was continuously negative (Table 1).

Table 1.

Under-5 years mortality rate (deaths per 1000 live births) inequity by economic status, education level, sex and residence area in Uganda (Years 1995, 2000, 2006, 2011)

| Inequality dimension | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2011 |

| Quintile 1(poorest)Estimate | 191.8 | 159.5 | 165.0 | 124.0 |

| Quintile 2 Estimate | 150.5 | 138.9 | 148.1 | 123.1 |

| Quintile 3 Estimate | 163.5 | 143.5 | 150.0 | 98.4 |

| Quintile 4 Estimate | 156.7 | 188.0 | 137.3 | 102.4 |

| Quintile 5( richest) Estimate | 113.4 | 147.8 | 111.4 | 71.1 |

| Relative concentration index | −7.7 | 0.1 | −6.1 | −9.1 |

| No education | 175.9 | 185.9 | 164.7 | 133.1 |

| Primary education | 154.4 | 153.8 | 145.1 | 103.9 |

| Secondary education + | 94.1 | 92.8 | 91.9 | 79.4 |

| Relative concentration index | −6.6 | −7.8 | −6.4 | −7.6 |

| Female | 151.4 | 148.7 | 129.1 | 97.4 |

| Male | 161.7 | 163.3 | 159.0 | 113.5 |

| Difference | 10.2 | 14.6 | 29.9 | 16.2 |

| Rural | 159.4 | 163.1 | 147.7 | 109.8 |

| Urban | 133.6 | 99.0 | 116.6 | 76.1 |

| Difference | 25.8 | 64.2 | 31.1 | 33.7 |

Converge of BCG immunization among children of less than one year was 57.95% among people without education, 85.4% for primary educated people, and 95.3 among people attending secondary school or above in 1995. It was decreased to 70.9% for the first group and 79, 5% In the second group, and 90.4% in 2000. Then, it was started to increase in 2006 and reached 89.7%, 89.9%, and 94.6% respectively for people without education, primary education and people with secondary and above education. The relative concentration index for the difference between rich and poor people were 3.0 in 1995, (−1.3) in 2000, (−1.0) in 2006, and (−0.5) in 2011. BCG immunization converges for children less than one year was 82.5 % for female and 85% for male in 1995. This percentage decreases in 2000 and converge with BCG vaccination became 77.5% in female and 80% in male. In 2011 the BCG coverage reached 93% for female and 94% in male. The BCG coverage in rural areas is 82.4%, (1996) 77.0% (2000), 90.4% (2006), and 93.3% (2011) respectively. Whereas the BCG in Urban areas is 93.3%, (1996) 91.8 % (2000), 92.0% (2006) and 96.3% (2006) and 96.3% (2011) (Table 2).

Table 2.

BCG vaccination coverage (%) among one year cold inequality according to the economic status, education level, sex, and residence area in Uganda (Years 1995, 2000, 2006, 2011)

| Inequality dimension | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2011 |

| Quintile 1(poorest) | 79.6 | 80.9 | 93.9 | 95.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 78.2 | 84.2 | 90.1 | 94.6 |

| Quintile 3 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 87.9 | 92.4 |

| Quintile 4 | 85 | 66 | 95.6 | 90.6 |

| Quintile 5( richest) | 92.4 | 80.2 | 94.6 | 94.7 |

| Relative concentration index | 3.0 | −1.3 | −1.0 | −0.5 |

| No education | 75.9 | 70.9 | 89.7 | 92.5 |

| Primary education | 85.4 | 79.5 | 89.9 | 93.8 |

| Secondary education + | 95.3 | 90.4 | 94.6 | 94 |

| Relative concentration index | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Female | 82.4 | 77.8 | 91.1 | 93.3 |

| Male | 85.0 | 79.6 | 89.9 | 94.1 |

| Difference | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Rural | 82.4 | 77.0 | 90.4 | 93.3 |

| Urban | 93.7 | 91.8 | 92.0 | 96.3 |

| Difference | 11.3 | 14.8 | 1.6 | 14.8 |

The coverage of under-5 yearschildren among male children who received oral dehydration therapy was 51% and 45.5 % with a difference of 5.6 when taking female as a baseline group in 1995. This percentage decreased among both females (46.8%) and males (40.5) in 2011, but the difference increased again between the two groups. The dehydration therapy among under - 5 children was assessed for both rural and urban areas with slight increase among people living in urban areas. The relative concentration index for rich and poor people regarding oral rehydration coverage among children aged < 5 years with diarrhea was 2.4, 3.8, −4.5, 2.4 for the surveys conducted in 1995, 2000, 2006, and 2011 respectively. In addition, the relative concentration index for the educated and people without any education was −0.2 in 1996, 1.8 in 2000, −3.8 in 2006 and 0.7 in 2011. The relative concentration index for rich and poor people regarding oral rehydration coverage among children aged < 5 years with diarrhea was 2.4, 3.8, −4.5, 2.4 for the surveys conducted in 1995, 2000, 2006 and 2011 respectively. In addition, the relative concentration index for the educated and people without any education was −0.2 in 1996, 1.8 in 2000, −3.8 in 2006 and 0.7 in 2011 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Children aged < 5 years with diarrhea receiving oral rehydration coverage (%) inequality according to the economic status and education and area of residence in Uganda (Years 1995, 2000, 2006, 2011)

| Year | Quintile | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile | Quintile 5 | Relative |

| 1(poorest) | Estimate | Estimate | 4 | (richest) | concentration | |

| Estimate | Estimate | Estimate | index | |||

| 1995 | 46.3 | 47.5 | 46.5 | 49.0 | 54 | 2.4 |

| 2000 | 29.3 | 34.8 | 30.1 | 39.3 | 34.9 | 3.8 |

| 2006 | 46.1 | 37.7 | 34.1 | 38.8 | 37.5 | −4.5 |

| 2011 | 42.9 | 40.4 | 40.9 | 50.7 | 45.4 | 2.4 |

| No education | ||||||

| Primary education | Secondary education+ | |||||

| 1995 | 49.7 | 46.5 | 54.5 | −0.2 | ||

| 2000 | 32.8 | 32.8 | 41.3 | 1.8 | ||

| 2006 | 45.1 | 37.7 | 37.4 | −3.7 | ||

| 2011 | 47.7 | 41.6 | 47.9 | 0.7 | ||

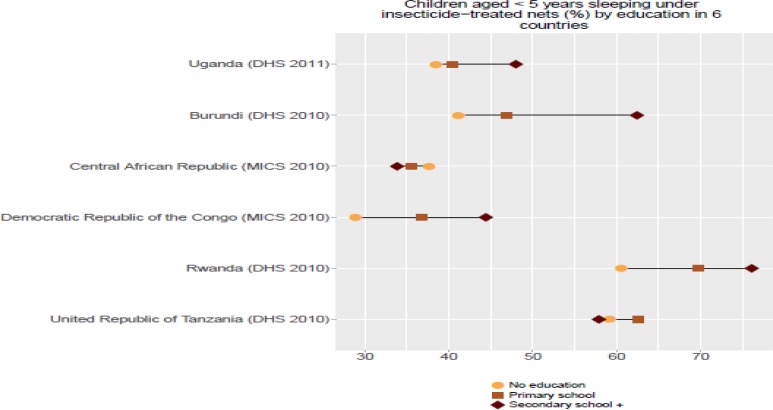

The percentage of children under-5 years sleeping under insecticide treated nets was very low (10%) for both males and females in 2006. This percentage increased to 42% in 2011. However, distribution of insecticides treated nets (ITNs) in rural areas was 8.4% compared to 19.5% in urban areas in 2006. The coverage of insecticide treated nets reached 41.5% and 43.7% respectively in 2001 for rural and urban areas respectively. The percentage of sleeping under insecticide treated nets was only 7.3 among people without education, 8.7% in people with primary education, and reached 17.4% among people with secondary education and above in 2006. This number increased in 2011 and became 38.5% for people without education, 40.4% for people with primary education and 48% for people with secondary education or more. The percentage ofUnder-5years childrenwho had pneumonia and were visiting healthcare facility was 62.6% and 60.1 for female and male children respectively in 1995. This percentage increased to 70.9% for female and 75.7 male children in 2006. It became better in 2011 and reached 82.8% for female children, but it decreased to 75.9%. among male children. The difference in the percentage between rural and urban areas regarding taking Under-5 yearswith pneumoniatohealthcare facility was 16.3 in 1995, 15.4 in 2000, −5.2 in 2006 and 2.4 in 2011.

In 1995, people with no education who were their children to healthcare facility was 52.2%, while the percentage of children in a family that has primary or secondary education and above was 65.3% and 695 respectively. Then, this difference decreased in 2000 to 16.9 and became very small (3.1) in 2006. On the other hand, in 2011, the difference between people who haddifferent levels of education became high reaching 13.3 in 2011. There wasa continuous decrease in the prevalence of underweight in children less than 5 years in both males and femalesbetween year 1996 and 2011. Also, this situation was similar among people living in urban and rural areas (Table 4). In Uganda, the percentage of underweight among children less than 5 years is low in both males and females compared to neighboring countries. The economic status relative concentration index for the underweight in children aged < 5 years is negative in all surveys conducted in Uganda in the years 1995, 2006 and 2011. Moreover, the inequality is higher among people without education than among educated people. The economic status inequality index regarding the coverage of full immunization for children of less than one year was 9.6 in 1995, −5.4 in 2000, 3.3 in 2006 and 1.0 in 2011. The inequality index between the educated and people without education was 8.3 in 1995, 8.5 in 2000, 5.5 in 2006 and 5.0 in 2011. There was no inequality between males and females in the access to immunization programme in Uganda. Although the immunization coverage is low in both urban and rural areas, the inequality is pronounced in rural areas (Table 5).

Table 4.

Underweight prevalence in children aged < 5 years coverage (%) inequality according to the economic status, education level, sex, residence area in Uganda (Year 2011)

| Inequality dimension | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2011 |

| Quintile 1(poorest)Estimate | 25.8 | 19.3 | 20.1 | 17.2 |

| Quintile 2 Estimate | 24.3 | 14.5 | 15.7 | 14.3 |

| Quintile 3 Estimate | 19.4 | 17.6 | 16.2 | 18.3 |

| Quintile 4 Estimate | 20.8 | 17.8 | 16.7 | 8.5 |

| Quintile 5( richest) Estimate | 12.8 | 19.0 | 9.0 | 8.6 |

| Relative concentration index | −11.2 | 1.0 | −10.0 | −12.9 |

| No education | 23.1 | 24.6 | 20.4 | 18.9 |

| Primary education | 21.0 | 16.7 | 15.7 | 13.6 |

| Secondary education + | 14.0 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 10.8 |

| Relative concentration index | −5.5 | −10.8 | −10.8 | −7.6 |

| Female % | 18.4 | 16.3 | 13.7 | 12.8 |

| Male % | 23.5 | 19.9 | 17.7 | 14.5 |

| Difference | 5.1 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.7 |

| Rural % | 22.0 | 19.0 | 16.3 | 14.8 |

| Urban % | 12.1 | 9.2 | 11.2 | 6.6 |

| Difference | 9.8 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 8.2 |

Table 5.

Full immunization coverage (%) among one year old inequality according to the economic status, education level, sex and residence area in Uganda

| Inequality dimension | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2011 |

| Quintile 1(poorest) | 34.6 | 39.6 | 42.0 | 52.1 |

| Quintile 2 | 46.0 | 40.1 | 45.2 | 52.4 |

| Quintile 3 | 49.3 | 44.6 | 49.1 | 49.9 |

| Quintile 4e | 47.4 | 31.4 | 51.3 | 52.8 |

| Quintile 5( richest) | 63.1 | 32.7 | 47.9 | 55.4 |

| Relative concentration index | 9.6 | −5.4 | 3.3 | 1.0 |

| No education | 38.7 | 28.3 | 39.2 | 45.3 |

| Primary education | 48.4 | 37.4 | 47.0 | 50.5 |

| Secondary education + | 68.1 | 51.4 | 58.1 | 61.8 |

| Relative concentration index | 8.3 | 8.5 | 5.5 | 5.0 |

| Female % | 46.8 | 37.2 | 47.7 | 52.6 |

| Male % | 48.5 | 36.4 | 46.2 | 52.5 |

| Difference | −1.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.1 |

| Rural % | 46.6 | 36.1 | 46.5 | 51.1 |

| Urban % | 56.1 | 42.3 | 51.1 | 61.5 |

| Difference | 9.6 | 6.1 | 4.7 | 10.5 |

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, inequality among Under-5 years children was observed. People who lived in rural areas sufferred from inequality compared with those who lived in rural areas. Also, inequality among femaleswas highercompared to the one among males. Moreover, poor and uneducated people were more likely to have unequal health services than rich and educated people. Inequality in mortality rate for under-5 children was high among the poorest people who did not have any education. It is clear that the inequality among poor people was higher compare them to rich people from 1996 up to 2011. Also, inequality of under-5 mortality was high among poor people, and efforts are needed to decrease this inequality through empowering poor communities. However, the uncer-5 mortality rate decreased in all economic quintiles. This finding is supported by another study conducted in Latin America where which made similar conclusion (6).

In Uganda, under five mortality rate was low among female comparedto males. There was an obvious inequality between females and males, and it was very high particularly in 2006. This situation became better in 2011, but still there was inequality between the two groups. Inequality is high among people living in rural areas comapredto those living in urban areas. Furthermore, there was a clear inequality in the BCG converge among different levels of education with slope index equaled to 23.1 in 1995. On the other hand, an obvious decline in inequality was observed from 1995 up to 2011. This difference became very slight in 2011 where the slop index among different group was 1.4. The BCG coverage was higher among poor people in 1996, and it started to become more among rich people in the following surveys (2000, 2006 and 2011). Generally, inequality among poor was more than among rich people. Generally, female children less than one year had less BCG immunization converge in the period from 1995 to 2011. Inequality in BCG vaccination converge was severe in 1995, but the difference between female and male became very small in 2011. This indicated that some improvement targeting female children was achieved. In different surveys conducted in Uganda for BGC coverage, the relative concentration was always positive which indicated that the inequality in rural areas washigher than the one in urban areas. There is a clear inequality between males and females in providing rehydration for children of less than five years who had diarrhea. Females had better converge in 1996 whereas males had better converge in 2006.

Females had better converge compared with men in 2011. A smilarconditionwas observed in Central Republic of Africa, Tanzania where females had slightly better coverage (7). Although the coverage in Burundi was lower than in Uganda in general, there was no inequality between females and males. This situation is different in countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda, where males have better coverage compared to females. Inequality regarding oral rehydration coverage for children aged < 5 years with diarrhea was among poor people in 1996, 2000, 2011, and among rich people in 2006. However, within regard to education level, the situation was exchangeable between rich and poor. In 2006 for instance, the inequality was among educated people, where as in 2000, the inequality was among people without education. Different studies indicated that one-fifth of child deaths were due to infection with diarrheal diseases; good care provision can prevent this (8).

In Ethiopia, inequality in providing rehydration therapy was very clear; people with high secondary school had high percentage coverage while people without education had the lowest percentage coverage. In Central Republic of Africa and Rwanda, people without education had the lowest percentage coverage, whereas people with high education had higher coverage. In general, Uganda has low inequality in the rehydration therapy for children under 5 and high converge percentage comparedto countries bordering it, such as Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Although the coverage of insecticides treated nets was very low in Uganda, no inequality was observed between males and females in 2006. Despite the increase in the insecticides treated nets coverage in 2011, there was slight inequality between females and males. The inequality of insecticides treated nets coverage was high among people living in rural areas in 2006. This inequality decreased to low difference between urban and rural areas in 2011. Uganda, Central Republic of Africa and Demogratic Republic of Congo had low INTs converge, but the inequality between males and females was high. Rwanda and Tanzania had good INTs converge and moderate inequality among sex groups. Burundi had both low inequality and low coverage of INTs.

The difference in the percentage of children sleeping under insecticides treated nets among different education levels was 11 in 2006. This number slightly increased in 2011 and became 12.7. It was clear that the knequality was high among people without basic education and then people with primary education. Uganda had a better situation in the inequality of children sleeping under insecticides treated nets comparedto Burundi, Tanzania and Rwanda, but it is worse compared to Central Republic of Africa. In all African countries, less than 41% of children under five were sleeping under insecticides treated nets (9). Inequality between males and females was well noticed in 1996, but the difference between the two groups was not too much. The inequality among females is lower than among males where the difference was negative considering females as baseline group in the year 2000 and 2006. On the other hand, the inequality between females and males wasvery high in 2011. The percentage of under-5 children who suffered from pneumonia and weretaken healthcare facility in Uganda was higher than the one in Central Republic of Africa, Ethiopia and Democratic Republic of Congo. On the other hand, inequality was higher among females and males comparing Uganda with neighboring countries such as Burundi, Rwanda and Ethiopia. In Africa, a significant number of children lack access to health services or services that meet their needs due toweak health systems (10). The inequality difference among educated and non-education people intaking their under-5 children with pneumonia to health facility was very high in 1996. The difference in inequality decreased in 2006, and increased again in 2011. Uganda had the highest coverage of pneumonia among Under-5 yearswho was being able to access health facility compared to Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda. On the other hand, Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, had low converge of children with pneumonia accessing health facilities, but the country had low inequality between people with different levels of education. Even in developed country such as Italy, economic inequality could happen and affect life expectancy at birth (11). Underweight inequality among female and male children of less than 5 years was obvious. Inequality in maleswas more than the one in female. Inequality among people living in rural areashigher than among people in urban areas. In most of the developing countries especially in Africa, underweight inequality is more obvious among people living in rural areas (12).

Monitoring and supervision programme can help countries such as Uganda to narrow the gap in inequality. Under-5 years children health represents good indicators and appropriate approach that could be targeted by health policy makers in any country. Inequality in the majority of African countries is nearly similar to the situation in Uganda. Poverty might be the main cause of this inequality plus other related factors because the majority of the population living in Africa is poor. Therefore, the first step to tackle this inequality is by reducing poverty among people living in this continent. Although governments have a great role in achieving equality, healthcare providers should fight to achieve equality as well.

Figue 1.

Inequality of Children < 5 years sleeping under insecticides treated nets ITNs in Uganda, Central Republic of Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Democratic republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi, 2011.

References

- 1.Health Inequality and the Role of Global Health Partnerships. The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millennium Development Goals report 2010. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uganda population. [July 2016]. http://countrymeters.info/en/Uganda.

- 4.The World Bank Indicators. [2017]. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT.

- 5.Hosseinpoor A, Nambiar D, Schlotheuber A, Reidpath D, Ross Z. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2016;16:141. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0229-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Childern aged under five years with Diarrhea receiving oral rehydration therapy and continued feeding in Tanzania. DHS: United Republic of Tanzania; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo-Méndez MC1, Barros AJ1, Requejo J2, Durán P3, Serpa LA2, França GV1, Wehrmeister FC1, Victora CG1. Progress in reducing inequalities in reproductive, maternal, newborn,’ and child health in Latin America and the Caribbean: an unfinished agenda. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R. educing deaths from diarrhea through oral rehydration therapy. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1246–1255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO), author World Health Statistics 2015. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambo LG, Kirigia JM. Investing in health systems for universal health coverage in Africa. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;28:14–28. doi: 10.1186/s12914-014-0028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vogli R1, Mistry R, Gnesotto R, Cornia GA. Has the relation between income inequality and life expectancy disappeared? Evidence from Italy and top industrialized countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:158–162. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wojcicki The double burden household in sub-Saharan Africa: maternal overweight and obesity and childhood under nutrition from the year 2000: results from World Health Organization Data (WHO) and Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]