Abstract

The type 2 immune response is critical for host defense against large parasites such as helminths. On the other hand, dysregulation of the type 2 immune response may cause immunopathological conditions, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, and anaphylaxis. Thus, a balanced type 2 immune response must be achieved to mount effective protection against invading pathogens while avoiding immunopathology. The classical model of type 2 immunity mainly involves the differentiation of type 2 T helper (Th2) cells and the production of distinct type 2 cytokines, including interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) were recently recognized as another important source of type 2 cytokines. Although eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils can also express type 2 cytokines and participate in type 2 immune responses to various degrees, the production of type 2 cytokines by the lymphoid lineages, Th2 cells, and ILC2s in particular is the central event during the type 2 immune response. In this review, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of how ILC2s and Th2 cells orchestrate type 2 immune responses through direct and indirect interactions.

Keywords: Type 2 immune response, type 2 T helper cell (Th2), Group 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2), Allergy and asthma

Subject terms: T-helper 2 cells, Innate lymphoid cells, Allergy

Introduction

The type 2 immune response is mediated by various cytokines that regulate diverse cellular functions, ranging from anti-helminth parasite immunity to allergic inflammation, wound healing, and metabolism.1–6 A diverse variety of compounds, including macroscopic helminth worms, microscopic particles and soluble enzymes, can elicit type 2 immune responses, which are orchestrated by several cell types.7 However, in this review, we will mainly discuss the two major players in type 2 immune responses, namely, type 2 T helper (Th2) cells and group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s).

The type 2 immune response often causes eosinophil recruitment to inflamed sites, which is one of the characteristic features of type 2 immunopathologies, including asthma, rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and anaphylaxis.8,9 In addition to eosinophilia, such responses also include basophilia and the recruitment of mast cells and alternatively activated M2 macrophages. Asthma is the one of the most prevalent type 2 immunopathologies. The clinical feature of asthma is airway obstruction, which directly results from the inflammation of airway mucosa-associated tissue. The type 2 immune response is elicited by the concatenated events enforced by type 2 cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. IL-4 induces IgE production; then, IgE along with antigen forms immune complexes that bind to high-affinity IgE receptors (FcεR1) on basophils and mast cells, causing the degranulation and release of several proinflammatory mediators, such as histamine, heparin, and serotonin,10 which in turn are responsible for the immediate symptoms of the acute allergic response, including bronchoconstriction. IL-5 is responsible for the activation and recruitment of eosinophils from bone marrow into the tissue, leading to eosinophilic airway inflammation. IL-9 causes mast cell activation. IL-13 induces goblet cell hyperplasia, mucus hypersecretion and smooth muscle hyperreactivity.

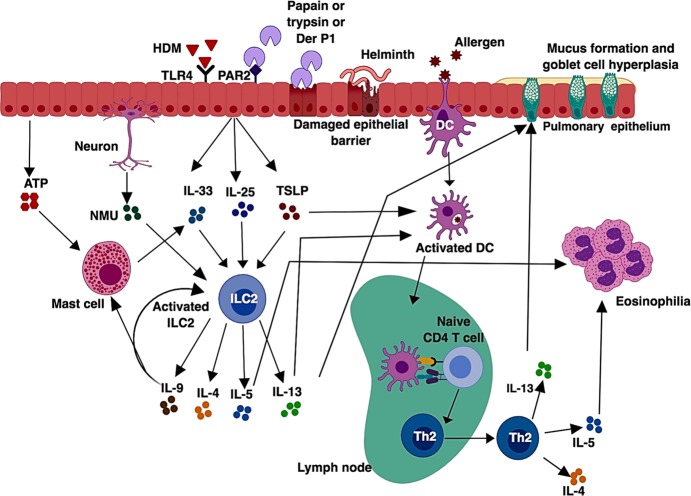

The traditional perception of type 2 immune responses is largely focused on the generation of Th2 cells (Fig. 1). In this model, antigen is taken up by specialized DCs, which then migrate to local draining lymph nodes, where these DCs activate and instruct naïve CD4+ T cells to become Th2 cells. Differentiated Th2 cells then egress from the lymph nodes and enter into the tissue, where they produce effector cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13.11,12 However, this model cannot rationalize a rapid induction of the type 2 immune response in RAG-deficient mice, in which T cells are absent.

Fig. 1.

Classic model of a type 2 immune response. In allergic asthma or during helminth infection, an allergen or a helminthic antigen is phagocytosed by dendritic cells, which then migrate to the draining lymph node, where naïve CD4+ T cells recognize the processed antigen presented by the peptide-MHC-II complex along with costimulatory molecules. After recognition of antigen presented by dendritic cells (DCs), naïve CD4+ T cells differentiate into effector Th2 cells. Th2 cells migrate into the site of inflammation and produce Th2 cytokines such as IL-5, which is responsible for eosinophilia, and IL-13, which promotes mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia. Th2 cells also produce IL-4, which is involved in antibody class switching and the production of IgE

In recent years, it has become clear that, in addition to adaptive lymphoid cells, there are lymphocyte-like innate cells that play important roles in immunity and inflammation. These cells are now designated as ILCs and are also considered the innate counterparts of adaptive T helper cells. These cells can be classified into group 1 ILCs (ILC1s), which produce IFN-γ and depend on the transcription factor T-bet for their development; group 2 ILCs (ILC2s), which produce IL-5, IL-13, and IL-9 and require GATA3; and group 3 ILCs (ILC3s), which mainly produce IL-22 and IL-17A and need RORγt for their development and function.13–17

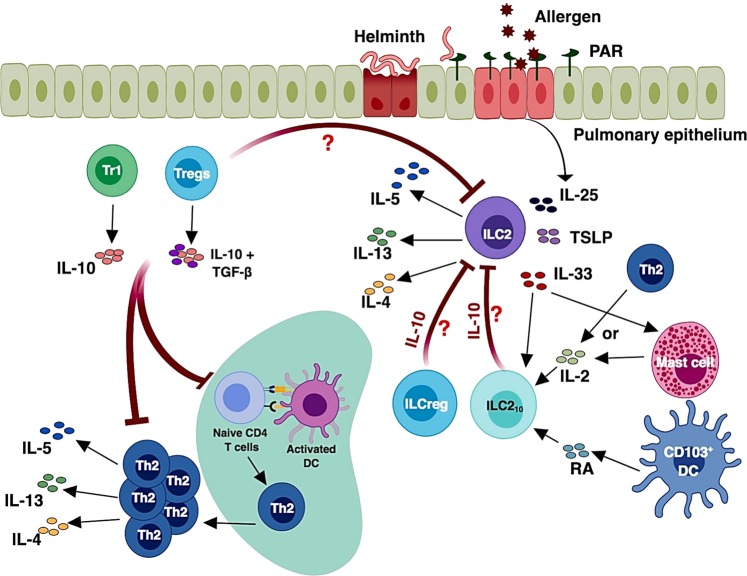

In the context of type 2 immune responses, the discovery of ILC2s has expanded our understanding from the classical DC-Th2-centric view to an ILC2-DC-Th2 axis (Fig. 2). In this new model, ILC2s are activated by epithelium-derived cytokines, including IL-33, IL-25, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP).18 These molecules elicit the production of type 2 cytokines by ILC2s. Interestingly, ILC2s constitutively express certain levels of IL-5, even in steady state, while IL-13 production is induced during type 2 inflammation.19 Although ILC2s mainly express IL-5 and IL-13, some ILC2s may express low levels of IL-4 under certain circumstances.20,21 In fact, IL-4 production by ILC2s may promote food allergy22 and induce Th2 cell differentiation during worm infection.23 Type 2 cytokines secreted by either ILC2s or Th2 cells (or both) result in the recruitment and activation of granulocytes, including eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils. Thus, both ILC2s and Th2 cells can induce type 2 immune pathology by releasing type 2 effector cytokines.

Fig. 2.

Type 2 immune response from the perspective of the ILC2-DC-Th2 cell-centric axis. Pathogen sensing or tissue damaging signals induced by exposure to helminth infection or protease allergen result in the secretion of alarmins, such as IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP. ATP released from epithelial cells may also induce mast cells to produce IL-33. These alarmin cytokines activate ILC2s, resulting in the production of the type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13. The neuropeptide neuromedin U (NMU) can also activate ILC2s. The type 2 cytokines secreted by ILC2s may support the differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into effector Th2 cells. Additionally, DCs receive signals from IL-13 secreted by ILC2s and TSLP released by epithelial cells during pathogen sensing and become capable of inducing effector Th2 cell differentiation from the naïve CD4 T cell population. IL-9 produced by ILC2s may act on these ILC2s to promote cell expansion as well as recruit mast cells. Overall, the type 2 cytokines secreted by ILC2s and Th2 cells, especially IL-5 and IL-13, cumulatively contribute to type 2 immunopathology

In this review, we summarize recent advances in studying the relative contributions of the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system during type 2 immune responses. We begin with a discussion of epithelial cells as a hub for the initiation of type 2 immune responses, how the immune system senses a diversity of allergens, and how tissue-derived signals are crucial for activating and inducing ILC2s and Th2 cells. Second, we focus on how Th2- and ILC2-mediated immune responses are initiated and orchestrated. Third, we discuss how ILC2s modulate the type 2 immune response via regulating Th2 cell activation and function. Finally, we conclude by highlighting some key questions to enhance our understanding of type 2 immune responses.

Type 2 immune response initiated by epithelial cells

The epithelial cell barrier not only represents the first line of defense against invading pathogens but also provides instructive signals that program DCs and Th2 cells (and/or ILC2s) to mount type 2 immune responses. The mucosal resident epithelial cells function as specialized tissue sentinels to detect a broad array of stimuli, including allergens and pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, and helminths. The first step in the initiation of the type 2 immune response occurs when the products of allergens or helminths are sensed. Compared to bacterial and viral products, the immune initiation signals triggering a type 2 immune response are more complex, ranging from macroscopic helminths to microscopic particles, including chitins, pollens, house dust mites, and soluble enzymes (e.g., proteases). Upon exposure to helminth parasites or allergens, epithelial cells produce a variety of cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-33, IL-25, GM-CSF, and TSLP, and inflammatory mediators such as uric acid and ATP.

Type 2 immunity requires the complex coordination of multiple cell types at the epithelial barrier. In response to type 2 stimuli, epithelial cells can also express chemokines, including CCL17, CCL22, and eotaxins (CCL11, CCL24, and CCL26), leading to the recruitment of DCs, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and Th2 cells.24 Epithelial cells also express a set of cytokines that educate DCs in promoting adaptive Th2 cell immunity and activate ILC2s, basophils, eosinophils, and mast cells.20,25–27 DCs exposed to IL-33 may promote the differentiation of IL-5- and IL-13-producing T helper cells from naïve CD4 T cells; the adoptive transfer of IL-33-treated DCs into naïve mice enhances lung airway inflammation.28 Furthermore, TSLP induces OX40 ligand (OX40L) expression on DCs, and OX40L expressed on activated DCs induces Th2 cell differentiation.29

In addition to the alarmins, epithelial cells also produce danger-associated molecular patterns (e.g., ATP and uric acid) upon exposure to allergen. Both humans and mice were shown to release ATP and uric acid in bronchoalveolar lavage upon exposure to HDM,30,31 which plays a crucial role in the induction of IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP secretion by epithelial cells. Furthermore, in response to ATP released from apoptotic epithelial cells after worm infection, mast cells may also produce IL-33 and thus are involved in the initiation of type 2 responses.32 Interestingly, IL-25 is constitutively expressed by tuft cells in the gut and is important for maintaining ILC2 homeostasis.33–35 During a type 2 immune response, IL-25 induces IL-13 production by ILC2s, and IL-13 produced by ILC2s and/or Th2 cells can promote the differentiation and expansion of tuft cells, resulting in a positive feedback loop.33 The type 2 immune response also involves other cells, including alternatively activated M2 macrophages. The release of pro-inflammatory mediators by these cells is critical for expelling helminth parasites, although this process also causes significant tissue damage and altered tissue function.4,36

Many cysteine proteases, such as papain and Der p1, from the HDM species D. pteronyssinus induce type 2 responses through disruption of the epithelial cell barrier via their proteolytic activity37. In addition to disrupting the epithelial cell barrier, these proteases can also activate respiratory epithelial cells by cleaving protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) on the cell surface,38,28. Many allergens with serine protease activity, including trypsin, also depend on the activation of PAR2 to induce allergic responses.39,40

Some reports suggest that low levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induce Th2 responses, and the allergenicity of certain allergens such as house dust mite (HDM) relies on Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4.41,42 It is also reported that most aerosol allergens, including HDM and chitin from cockroach exoskeleton, are usually contaminated with minute levels of LPS.43 Similar to antigen-presenting cells, epithelial cells also express TLRs.44,45 Triggering TLR activation on epithelial cells results in the production of several cytokines, including IL-1α, TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33 (Fig. 2).46,47 The release of IL-1α induced by HDM is considered to occur upstream of the cytokine secretion cascade. The IL-1α released by epithelial cells acts in an autocrine manner to trigger the release of GM-CSF and IL-33.47 These cytokines in turn cause the cascade of allergic events via activation of mucosal DCs and tissue-resident ILC2s. Interestingly, TLR4 expressed by lung epithelial cells but not DCs is necessary and sufficient for HDM-induced DC activation and Th2 cell differentiation.46

The epithelial barrier surfaces, including skin, gut and the airway, are densely populated by neurons, and crosstalk between the nervous system and several immune cells has been recently reported.48–50 Likewise, ILC2s also respond to the signals mediated by the nervous system at the epithelial barrier. ILC2s express neuromedin U receptor 1 (Nmur1) on their surface, and the nervous system regulates ILC2 activation via neuromedin U (NMU) secretion.51,52 Coordinated neuron-ILC2 crosstalk contributes to protective immunity and worm expulsion. Furthermore, ILC2s express β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), which interacts with the neurotransmitter epinephrine. In contrast to NMU, β2AR agonists diminish the ILC2-mediated immune response, indicating that the β2AR signaling pathway negatively regulates ILC2 activity.53

Type 2 immune response mediated by Th2 cells

An important component of the type 2 immune response is the process by which antigen-specific naïve CD4 T cells differentiate into Th2 cells. DCs residing at the antigen-exposed area first take up antigens, process them, and then present them via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (MHCII) molecules. Next, DCs migrate to the draining lymph nodes, where a small number of antigen-specific naïve CD4 T cells encounter the DCs through T cell receptor (TCR)/peptide-MHCII interactions in the presence of costimulatory molecules and cytokines and become activated. These activated CD4 T cells proliferate and differentiate into effector Th2 cells before they migrate into sites of inflammation.11

The cytokine environment plays a crucial role during the differentiation of Th subsets.54,55 Thus, IL-4 is involved in Th2 cell differentiation.56,57 IL-4-mediated STAT6 phosphorylation is essential for the generation of Th2 cells, particularly in vitro.58 However, IL-4-independent Th2 cell differentiation has been observed in vivo.7 DCs are essential for the differentiation of naïve CD4 T cells into Th2 cells in response to allergen exposure or helminth infection, which has been highlighted in models in which subset-specific depletion of DCs diminished the type 2 immune response to helminths and allergens.59–61

Th2 cells exert their functions through the production of various type 2 effector cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. Initially, IL-4 secreted by Th2 cells was thought to be important for regulating the class switch recombination of B cells to produce IgE. However, follicular T helper (Tfh) cells can also express IL-4 and thus may regulate the IgE response.62,63 Nevertheless, the role of Tfh cells in the development of type 2 immunity remains ambiguous. Some recent literature demonstrated that Tfh cells may contribute to type 2 immunity by serving as the precursors of effector Th2 cells.64 HDM challenge causes some Tfh cells to differentiate into IL-4 and IL-13 double-producing Th2 cells that accumulate in the lung and cause pathology. Furthermore, IL-21 secretion by T cells promotes the generation of effector Th2 cells.65 As mentioned earlier, IgE cross-linking with high-affinity Fc receptors for IgE (FcεR1) on granulocytes, including basophils and mast cells, results in their degranulation. IL-5 secreted by Th2 cells causes the recruitment and expansion of eosinophils from bone marrow.66 Furthermore, IL-4 and IL-13 secreted by Th2 cells may play indirect roles in eosinophilia in mucosal tissue by upregulating eotaxin-1 (CCL11) and eotaxin-3 (CCL26) expression by epithelial cells.67 IL-13 can also induce smooth muscle movement, goblet cell hyperplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, and mucus hypersecretion.68

Type 2 immune response mediated by ILC2s

Th2 cells were thought to be the characteristic hallmark feature of type 2 immunity; however, the discovery of ILC2s challenged this simple view. In fact, RAG-deficient mice, in which both T cells and B cells are absent, are still able to produce IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 treatment, and the induction of these cytokines may result in type 2-like immunopathology, including eosinophilia, epithelial cell hyperplasia, and increased mucus production, in the absence of Th2 cells.69 Such IL-5 and IL-13 production in response to IL-25 treatment is derives from c-Kit-expressing cells that are negative for T cell marker, B cell marker, and FcεR1.20 This novel lymphoid cell population, now known as ILC2, is actually also one of the main sources of type 2 cytokines during N. brasiliensis infection. This also explains why IL-4 and IL-13 production by Th2 cells is not essential for protective immunity again N. brasiliensis.15 In addition, intranasal administration of papain rapidly induces lung eosinophilia and mucus hyperproduction in RAG-deficient mice, which are mediated by IL-5 and IL-13 produced by lung ILC2s.26 Thus, ILC2s are a major source of type 2 cytokines during allergic lung inflammation and parasitic helminth infection, and these cells may elicit a type 2 immune response even in the absence of the adaptive immune system. Importantly, increased ILC2 cell numbers are also associated with many type 2 diseases in humans.70–73

ILC2s express CD127 (IL7Rα), T1/ST2 (IL33R), CD25 (IL-2Rα), CD90.2 (Thy1), KLRG1, and ICOS.74,75 While ILC2s are thought develop mainly in the bone marrow, they may also develop in the thymus and/or in tissue.76–78 The development of ILC2s critically depends on several important transcription factors, including inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2), RORα, and GATA3.79–86 Like Th2 cells, ILC2s are capable of producing type 2 cytokines, especially IL-5 and IL-13. ILC2s do not express receptors for antigens. Instead, as mentioned earlier, they mainly respond to cytokines, including IL-33, IL-25, and TSLP,13,14 that are rapidly released by epithelial cells upon damage because most ILC2s express T1/ST2 (an IL-33 receptor subunit), IL-17RB (a receptor for IL-25), and TSLPR.87–89 Exposure of ILC2s to epithelial-cell-derived cytokines induces ILC2 activation as well as the production of type 2 cytokines.

Early studies demonstrated that ILC2 proliferation can be enhanced by cytokines, such as IL-2 and IL-7, which signal through the common γ receptor.14,15 Bone marrow stromal cells, dendritic cells and epithelial cells are the main sources of IL-7. CD4 T cells are the major source of IL-2. Indeed, T cells collaborate with ILC2s to maintain M2 macrophages during worm infection, presumably through IL-2 secretion.90 Interestingly, IL-2 produced by ILC3s may also play an important role in the activation of ILC2s in RAG-deficient animals.91 Since IL-4 also uses the common γ chain, its functions in regulating ILC2-mediated immunity were studied. Mice acutely challenged with papain induce IL-4 production from basophils, which in turn regulates ILC2-mediated lung inflammation.92 ILC2s can also express low amounts of IL-4 during helminth infection, raising the possibility that IL-4 secreted by ILC2s might serve as an initial source of IL-4 in inducing Th2 cell differentiation.93

Another cytokine utilizing the common γ receptor for its signaling is IL-9. Interestingly, ILC2s themselves may transiently upregulate IL-9 expression during papain-induced lung inflammation. The results obtained from IL-9-fate mapping mice demonstrate that IL-9 production in papain-induced allergy is restricted to ILC2s.94 Although IL-9 expression by ILC2s is transient, IL-9 plays a very important role in the activation and survival of ILC2s. Neutralization of IL-9 results in reduced levels of IL-5 and IL-13 and thus a reduced type 2 immune response. The autocrine activity of IL-9 on ILC2s may also be involved in the differentiation and functions of Th2 cells. Additionally, IL-9 regulates amphiregulin secretion by ILC2s, which plays an important role in tissue repair during lung inflammation.95–97 In addition to cytokines, the neuropeptide neuromedin U, leukotrienes, prostaglandin D2 and the TNF family member TL1A can promote ILC2 activation and lung inflammation.51,52,98–101

Heterogeneity and plasticity of ILC2s

The classic view of innate lymphoid cells is characterized by the expression of a unique master transcription factor and cytokines that are critical for their distinct phenotypes and functions. However, many of these transcription factors may be expressed transiently or at low levels in different ILCs. For example, all ILC subsets express low levels of GATA3, and its expression is functionally important during the development and maturation of different ILC subsets.83,102,103 Recent literature indicates that environmental cues can elicit the phenotypic heterogenicity and functional plasticity of these cells. For example, RORγt+ ILC3s exposed to IL-12, IL-15, and/or IL-23 may upregulate IFN-γ and T-bet expression to become ILC1-like cells.104,105 Interestingly, even in the steady state, NKp46+ ILC3s co-express T-bet and RORγt.106 Thus, co-expression of multiple transcription factors may enable the plasticity and heterogeneity of ILCs in response to various stimuli.

Recent evidence indicates that ILC2s exhibit a certain degree of heterogeneity and plasticity as well. ILC2s found in different tissues express different sets of cytokine receptors and respond to selective inflammatory cytokines.107 ILC2s found in lung and fat tissues mainly express IL-33 receptor, while ILC2s in the gut largely express IL-25 receptor; strikingly, ILC2s found in the skin express functional IL-18 receptor but not IL-25 or IL-33 receptors.107,108 This explains why ILC2-dependent atopic dermatitis may occur in an IL-33-independent manner.89 It has been found that mice systemically injected with IL-25 generate inflammatory ILC2s (iILC2s). These iILC2s may co-express IL-13 and IL-17 under certain conditions.109 It has also been reported that exposure of ILC2s to IL-25 and Notch ligand induces the upregulation of transcription factor RORγt, and these cells may co-express IL-13 and IL-17.110 Interestingly, IL-17-producing ILC2s play a pathogenic role in a mouse model of lung allergy.111 At the molecular level, the transcription factors Bcl11b and Gfi-1 regulate the identity of ILC2s by repressing the expression of RORγt and its associated genes. Therefore, deletion of Bcl11b or Gfi-1 in ILC2s results in IL-17 production and loss of GATA3, IL-5, and IL-13 expression.112,113

Some reports also indicate the plasticity of ILC2s, allowing them to become ILC1-like cells. ILC2s that have experienced a type 1 proinflammatory milieu may upregulate T-bet and IL-12R; both human and mouse ILC2s have been shown to upregulate IFN-γ expression in an IL-12-IL-12R-dependent manner.114 In addition, IL-1β upregulates IL-12Rβ2 expression on ILC2s, which potentiates the ILC1 phenotype conversion in response to IL-12.115 The importance of IL-12-IL-12R signaling in the conversion of ILC2s to ILC1s has been further confirmed through an analysis of patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)116; disease severity in these patients is significantly associated with an altered ILC1/ILC2 ratio and the frequency of ILC1s. During influenza infection, ILC2s can also be activated, although at a late stage.117 However, whether some of these ILC2s will display a partial ILC1-like phenotype and whether conversion of some ILC2s to ILC1s has occurred in this infection setting is unknown.

Similarities and differences between Th2 cells and ILC2s

Both ILC2s and Th2 cells can efficiently regulate the type 2 immune response by producing similar sets of type 2 cytokines. Although Th2 cells can respond to antigen stimulation, both Th2 cells and ILC2s can respond to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-33 to produce their effector cytokines, as discussed above. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that IL-33/IL-25/TSLP signaling in differentiated Th2 cells after their migration to the lung tissue is necessary for these cells to gain effector functions, even in response to antigens.118 Not only do activated ILC2s and differentiated Th2 cells display very similar transcriptomes, but epigenetic status at the key regulatory elements of the effector-associated genes is also remarkably identical.119 Thus, ILC2s are considered the innate counterpart of the Th2 effector cell subset.119–122

Mice deficient in the expression of the transcriptional regulator Id2 lack all ILC lineages,82 whereas the development of T cells is largely unaffected. Like other ILCs, ILC2s may develop from common progenitors that reside in fetal liver, fetal gut, adult bone marrow, or peripheral blood.77,78,84,123–126 After their development, ILC2s reside in different tissues, including lung, gut, skin and fat tissues, and are present even in naïve mice. By contrast, effector Th2 cells are very rare in naïve animals but develop from activated naïve CD4 T cells during a type 2 immune response after encountering the cognate antigen.127,128 Thus, Th2 cell differentiation requires MHCII-antigen recognition; however, ILC2 development is independent of MHCII. Because ILC2s are predeveloped and tissue-resident cells, they can respond rapidly to infection and thus provide the first line of host defense. While ILC2s are largely tissue-resident,129 recent studies by Huang et al. show that IL-25 preferentially acts on inflammatory ILC2s in the gut, which can migrate to the lung tissue and actively participate in the expulsion of helminth parasites.109,130

After exposure to allergens, allergen-specific naïve CD4 T cells undergo activation and differentiate into effector Th2 cells. Later, the effector Th2 cells undergo contraction while leaving some long-lived memory T cells. Upon re-exposure to the same allergen, memory Th2 cells respond rapidly and produce type 2 cytokines. Similar to Th2 cells, some activated ILC2s may persist long after the resolution of inflammation. These ILC2s respond more potently than naïve ILC2s after exposure to allergens.131 Thus, both Th2 cells and ILC2s have memory, although memory ILC2s do not have antigen specificity.

Despite several differences, both ILC2s and Th2 cells can be activated by cytokines, such as IL-33, IL-25, and TSLP. Furthermore, both ILC2s and Th2 cells are regulated by costimulatory ICOS signaling. ILC2s express both ICOS and ICOS-L on their surface, and deletion of ICOS results in reduced ILC2 expansion and IL-33-induced bronchial inflammation.132 Similarly, ligation of ICOS is crucial for the activation of CD4 T cells, Th2 cell differentiation and lung inflammation.133–135 The secretion of type 2 cytokines, including IL-5 and IL-13, by both ILC2s and Th2 cells depends on the master transcription factor GATA-3.83,122,136,137

Innate functions of Th2 cells

Following pathogen clearance or disappearance of allergens, antigen-specific effector T cells as well as memory T cells either enter the circulation or reside in the tissue.138 Upon re-exposure to the same antigen, these memory T cells rapidly expand and produce effector cytokines. It has been long assumed that the TCR-MHCII interaction alone is sufficient for memory T cell reactivation and effector function.139 Although the expansion and functions of effector and memory T cells are regulated by antigen-specific TCRs that recognize peptide presented by antigen-presenting cells in the context of MHCII, T cell effector function can also be elicited by noncognate stimuli. Indeed, an inflammatory environment promotes noncognate stimulation of CD4 T cells, and differentiated CD4 T cells can also be activated by innate cytokines.140 In some cases, polyclonal Th2 cells can directly respond to the innate cytokine IL-33, just as ILC2s, and contribute to the pathogenicity of allergic disease by secreting IL-5 and IL-13.141 The noncognate activation of CD4 T cells may contribute to allergic inflammation and protection against parasitic infection in an antigen/allergen-independent manner. During a type 2 immune response, IL-33, a member of the IL-1 family of cytokines, may stimulate Th2 cells to produce type 2 effector cytokines.27,141 Thus, IL-33 may play an important role in allergic inflammation and immunity against parasitic infection by directly activating Th2 cells. IL-33 binds to its receptor and induces the activation of NF-kB and MAPK.27 T1/ST2, a subunit of the IL-33 receptor, is preferentially expressed by Th2 cells and a subset of ILC2s, and its expression is regulated by the transcription factor GATA3 in both cell types.83,136,142 Moreover, memory Th2 cells may upregulate T1/ST2 expression in response to IL-33 in addition to inducing the expression of type 2 cytokines.143 Furthermore, signaling via T1/ST2 in T cells provides posttranscriptional stability of the cytokine transcripts.144 The deletion of IL-33 or T1/ST2 results in impaired eosinophilic airway inflammation driven by memory Th2 cells.

Th2 immune response may be initiated by ILC2s

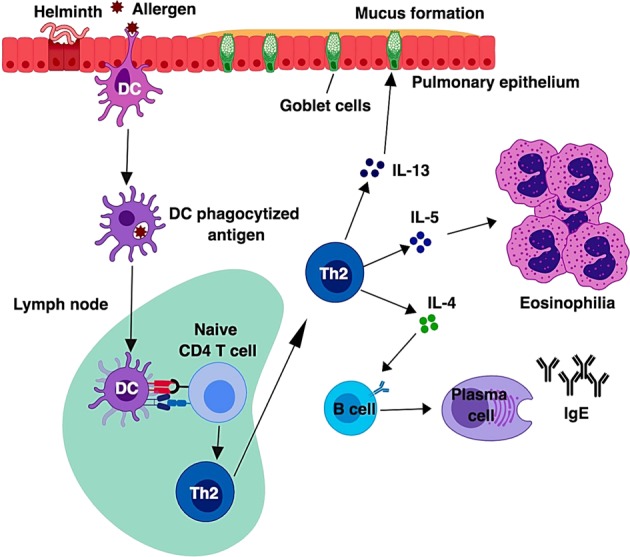

ILC2s directly contribute to type 2 immunopathology as discussed above; however, ILC2s may also orchestrate an adaptive Th2 response under certain circumstances (Fig. 3). Some reports suggest that Th2 cell differentiation can be initiated by ILC2s, particularly because ILC2s are activated during the early phase of type 2 immune responses.93,145 The importance of ILC2s in regulating the Th2 response has been demonstrated by studies using ILC2 depletion.93,146 Cooperation between ILC2s and Th2 cells has also been studied by the adoptive transfer of these cells into IL-7ra KO mice. Cotransfer of both cell types elicits a robust antigen-specific type 2 immune response; however, such a response is not observed in mice receiving these cells separately. Thus, ILC2s seem to regulate Th2 cell differentiation.146,147 Furthermore, IL-13 secreted by ILC2s promotes the activation and migration of lung dendritic cells into the draining lymph node, where they prime naïve CD4 T cells to differentiate into Th2 cells,145,55,148 However, this is not always the case, since Locksley and his colleagues have reported that Th2 cell differentiation in draining lymph nodes occurs normally during Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection in animals that are supposed to be devoid of ILC2s.118

Fig. 3.

ILC2s may play an important role in initiating a Th2 response. The pulmonary epithelial cells, which are primary sentinels of the lung, sense allergens and release alarmins, such as IL-33, IL-25 and TSLP, which activate ILC2s to produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and amphiregulin (Areg). In turn, IL-5 and IL-13 induce eosinophilia, mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia. Areg produced by ILC2s plays an important role in tissue repair. Activated ILC2s will initiate an adaptive effector Th2 response by either direct antigen presentation through cognate MHCII-TCR interactions along with costimulatory molecules or by secreting Th2-inducing cytokines such as IL-4. In some cases, the IL-13 secreted by ILC2s drives the activation of inactive CD11b+ DCs. The activated CD11b+ DCs migrate into the mediastinal lymph node, where naïve CD4 T cells differentiate into effector Th2 cells upon cognate MHCII-peptide-TCR interactions

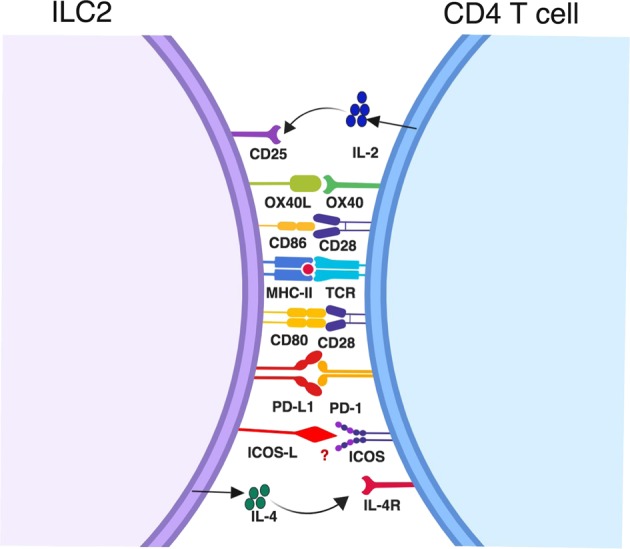

ILC2-T cell interactions may be required to generate an effective Th2 cell response. Although ILC2s are considered the counterpart of Th2 cells, some ILC2s can express MHC-II molecules, which allow ILC2s to directly modulate the CD4 T cell response.93,149 While ILC2s do not express TLRs in most cases, they may be activated by IL-33, as discussed above. Antigen-specific interactions between ILC2s and T cells through MHCII and TCR expressed on these cells, respectively, may contribute to CD4 T cell activation, differentiation and expansion.93,146 In addition to MHCII-TCR-mediated activation of T cells, the interaction between ILC2s and Th2 (or uncommitted T) cells through costimulatory molecules may also play an important role during type 2 immune responses (Fig. 4). The costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, in combination with MHCII, induce ILC2-mediated T cell activation. Indeed, ILC2s express CD80, CD86, ICOS, and OX40L on their surface, and activated T cells express receptors to these ligands.93,132,150 In some cases, the ILC2-CD4 T cell interaction is essential for ILC2s to exert an effector response. The importance of ILC2-CD4 T cell interactions was demonstrated by infecting IL-13-deficient mice reconstituted with either wild-type or MHCII-deficient ILC2s with N. brasiliensis. Strikingly, N. brasiliensis was expelled by the mice that had received wild-type ILC2s, however, mice that received MHCII-deficient ILC2s still showed impaired worm clearance.93 The ILC2-CD4 T cell interaction may lead to IL-2 secretion by CD4 T cells, which promotes a local type 2 response by activating ILC2s.

Fig. 4.

Direct interactions between ILC2s and CD4 T cells. CD4 T cells may directly interact with ILC2s through MHCII-peptide-TCR. ILC2s may also provide costimulatory signals to T cells through CD80, CD86, OX40L, and PD-L1. Additionally, it is possible that ILC2s induce naïve CD4 T cell differentiation into effector Th2 cells by secreting IL-4. Reciprocally, activated CD4 T cells may promote ILC2 expansion through IL-2 production

The ligation of OX40 ligand (OX40L) expressed on ILC2s with OX40 expressed on CD4 T cells is essential for the type 2 immune response.147 Expression of OX40L on ILC2s can be upregulated upon exposure to IL-33, and ILC2-specific deletion of OX40L significantly affects the responses of Th2 cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) following allergen exposure.150 Engagement of the PD-1 receptor with its ligand PD-L1 causes the inhibition of CD4 T cell-mediated immune responses.151,152 Although the PD-1-PD-L1 interaction has been described as a negative regulatory mechanism, ILC2-specific deletion of PD-L1 has a significant effect on N. brasiliensis worm clearance, and such mice exhibit impaired effector Th2 cell generation and IL-13 secretion.153 Activated ILC2s upregulate PD-L1, and the PD-1-PD-L1 interaction causes increased expression of GATA3 and IL-13 by CD4 T cells. ICOS is another costimulatory molecule. As discussed earlier, ICOS and the ICOS-ligand interaction have been shown to play critical roles in lung mucosal inflammation by regulating the production of Th2 cytokines.135,154 ILC2s express both ICOS and ICOS-L, and their expression can be induced by IL-2 and IL-7.132 ICOS-ICOS-L interactions among ILC2s cause ILC2 proliferation and activation.155,156 The blockade of ICOS-ICOS-L interactions diminishes the production of IL-5 and IL-13 from activated ILC2s both in vivo and in vitro. Although ILC2s mainly express IL-5 and IL-13, they do express some IL-4.20,21 Thus, ILC2s may serve as early responders during nematode H. polygyrus infection by producing IL-4 to induce Th2 cell differentiation. IL-4 deficiency in ILC2s causes impaired generation of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13-secreting CD4 T cells during H. polygyrus infection.23 Thus, crosstalk and direct interaction between ILC2s and CD4 T cells may contribute to the initiation, expansion and effector cytokine secretion of CD4 T cells as well as the maintenance of ILC2s.

Modulation of the type 2 immune response

Precise regulation of the magnitude and duration of an immune response is a result of balanced actions of effector and regulatory mechanisms in the immune system. Control of immune responses to self-antigens and the prevention of exacerbated immune responses to pathogens and/or allergens are the key controllers of the immune system. Tregs play a critical role in self-tolerance and prevent autoimmunity.157–159 The Th2 effector response may also be regulated by Tregs, a potentially important mechanism for the regulation of allergic diseases.160,161 The differentiation/development and suppressive functions of Tregs depend on the transcription factor Foxp3, which is also a marker for the identification of this suppressive T cell subset.162 IL-10-producing CD4 T cells, also called type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1), may control the effector Th2 response in an IL-10-dependent manner.163,164 The IL-10 secreted by Tregs and Tr1 cells as well as TGF-β secreted by Tregs may act at different stages of effector Th2 cell differentiation to control adaptive type 2 responses (Fig. 5). Whether Tregs and Tr1 cells can directly regulate the functions of ILC2s is not known. Although studies have shown that IL-33 is a proinflammatory cytokine, and DCs exposed to IL-33 promote Th2 responses, it has also been shown that IL-33-stimulated DCs enhance Treg differentiation by secreting IL-2.165 Strikingly, the IL-33 receptor ST2 is preferentially expressed by colonic Tregs, and the IL-33 signaling in Tregs enhances their functionality through their accumulation and maintenance in the inflamed tissue.166 Thus, IL-33R expression on Tregs renders them adaptable to the proinflammatory milieu. In addition, IL-9-activated ILC2s may induce Treg activation and proliferation and thus are involved in the resolution of chronic inflammation in an arthritis model.167

Fig. 5.

Modulation of the type 2 immune response. Pulmonary epithelial cells sensing pathogen and allergen direct the development of ILC2s and Th2 cells. The IL-10 secreted by Tregs or Tr1 cells and TGF-β secreted by Tregs act at different stages of effector Th2 cell differentiation and control adaptive Th2 cell immunity. The functions of Tregs in regulating ILC2s are unknown. The release of IL-33 from epithelial cells, along with IL-2 secretion by mast cells as well as retinoic acid secretion by CD103+ DCs, creates a favorable environment for the generation of ILC210 cells. The IL-10 secreted from ILC210 cells may suppress ILC2 activation and thus control the immunopathology caused by other type 2 cytokines. The effect of ILCregs on ILC2s remains to be tested

A recent finding indicates that a new subset of ILCs that are capable of producing regulatory cytokines may control ILC-mediated responses.168 This new subset of ILCs is designated ILCregs. Notably, unlike Tregs, ILCregs do not express the transcription factor Foxp3. By producing IL-10, ILCregs may control the activation of ILC1s and ILC3s in the intestine, leading to protection against innate inflammation. Although this work did not investigate the functions of ILCregs in suppressing ILC2s during type 2 inflammation, the suppressive effects of IL-10 and TGF-β on ILC2s have been proposed.169 All CD4 T helper subsets, including Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, are capable of producing IL-10. Whether there are IL-10-producing ILC1s and ILC3s that are immune suppressive requires further investigation. However, IL-10-producing ILC2s, termed ILC210 cells, have been discovered.170 The ILC210 population may control the type 2 immune response elicited by ILC2s via the secretion of IL-10. The ILC210 population can be generated during the chronic stage of allergy induced by exposure to papain or IL-33, and the ILC210 population undergoes contraction upon removal of the stimulus.170 Based on in vitro experiments, IL-33 along with IL-2 and retinoic acid induces alternative activation of ILC2s to generate ILC210. However, in RAG1-deficient mice, IL-33 significantly induces ILC210 cell expansion, demonstrating that IL-2 produced by T cells may not be required for ILC210 induction in vivo. IL-33-stimulated mast cells may produce IL-2 and thus possibly act as the source of IL-2 for ILC210 expansion.171 CD103+ DCs are a potent source of retinoic acid, and mice deficient in the CD103+ DC population show a reduction in the production of IL-10 from ILC210 cells, implying retinoic acid production by lung-resident CD103+ DCs may support the induction of alternatively activated ILC210. Finally, the activity of ILC2s may be negatively controlled by PD-1-mediated signaling172 and A20173 in a cell-intrinsic manner, and other non-Th2 cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-27, type 1 IFNs and IFNγ, may regulate the plasticity of ILC2s and Th2 cells.115,116,174–178

Conclusions

Initiation of the type 2 response takes place in the tissue sites where allergens or parasites are encountered. At the epithelial barriers, skin, lung and intestinal epithelial cells are responsible for sensing the products of allergens and helminth parasites to initiate type 2 immune responses in vivo by producing cytokines such as IL-33, IL-25 and TSLP. While Th2 cells, by producing IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, were initially believed to be the only major players driving the type 2 immune response, our current knowledge indicates that the type 2 immune response is mediated by the cooperative actions of Th2 cells and ILC2s.

Some studies have already shown that Th2 cell differentiation may be regulated by ILC2 activation under certain circumstances; however, Th2 cell differentiation may also occur without the involvement of ILC2s. More investigation is needed to reconcile these discrepancies. While it is possible that only certain types of Th2 responses depend on ILC2 activation, it is also likely that the discrepancies are due to the lack of consistent, reliable and specific ILC2-deficient mouse models.

It has also been shown that in a mild HDM model, ILC2 induction requires T cell activation.179,180 Therefore, future studies should also focus on how Th2 cells may modulate ILC2 activation and function in different disease models. ILCs and T helper cells are considered to be functionally redundant in host defense181; however, a recent study has demonstrated that the functions of T cells cannot be replaced by ILCs.182 Thus, it is likely that ILC2s and Th2 cells may also have unique functions in host defense and in type 2 inflammation. Future single-cell analyses of ILC2s and Th2 cells in multiple models with different kinetics will offer important insights into type 2 immune responses.

Understanding the molecular basis for the initiation of type 2 immune responses, the crosstalk between innate ILC2s and adaptive Th2 cells, and the relative contributions of ILC2s and Th2 cells in different disease models/settings, as well as the differences and similarities between ILC2s and Th2 cells, will be crucial for us to understand the mechanisms of type 2 diseases, such as chronic worm infections, allergic asthma, and atopic dermatitis, and to design immune interventions to treat these diseases.

Acknowledgements

R.K.G. and J.Z. are supported by the Division of Intramural Research of NIAID (US National Institutes of Health).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Rama Krishna Gurram, Email: rama.gurram@nih.gov.

Jinfang Zhu, Email: jfzhu@niaid.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Anthony RM, Rutitzky LI, Urban JF, Jr., Stadecker MJ, Gause WC. Protective immune mechanisms in helminth infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:975–987. doi: 10.1038/nri2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen F, et al. An essential role for TH2-type responses in limiting acute tissue damage during experimental helminth infection. Nat. Med. 2012;18:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nm.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu D, et al. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulendran B, Artis D. New paradigms in type 2 immunity. Science. 2012;337:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1221064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brestoff JR, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2015;519:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klose CS, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:765–774. doi: 10.1038/ni.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay AB. Asthma and inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1991;87:893–910. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90408-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd C. M., Snelgrove R. J. Type 2 immunity: expanding our view. Sci Immunol3, eaat1604 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Stone KD, Prussin C, Metcalfe DD. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;125(2Suppl 2):S73–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Biology of lung dendritic cells at the origin of asthma. Immunity. 2009;31:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambrecht BN, et al. Myeloid dendritic cells induce Th2 responses to inhaled antigen, leading to eosinophilic airway inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:551–559. doi: 10.1172/JCI8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moro K, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neill DR, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price AE, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zook EC, Kee BL. Development of innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:775–782. doi: 10.1038/ni.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie ANJ, Spits H, Eberl G. Innate lymphoid cells in inflammation and immunity. Immunity. 2014;41:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nussbaum JC, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallon PG, et al. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1105–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doherty TA, et al. Lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells express cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1, which regulates TH2 cytokine production. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Oettgen HC, Chatila T. IL-4 production by group 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes food allergy by blocking regulatory T-cell function. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;138:801–811 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelly VS, et al. IL-4-producing ILC2s are required for the differentiation of TH2 cells following Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1407–1417. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YJ. TSLP in epithelial cell and dendritic cell cross talk. Adv. Immunol. 2009;101:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allakhverdi Z, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:253–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmitz J, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Besnard AG, et al. IL-33-activated dendritic cells are critical for allergic airway inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:1675–1686. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito T, et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1213–1223. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kool M, et al. An unexpected role for uric acid as an inducer of T helper 2 cell immunity to inhaled antigens and inflammatory mediator of allergic asthma. Immunity. 2011;34:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Idzko M, et al. Extracellular ATP triggers and maintains asthmatic airway inflammation by activating dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2007;13:913–919. doi: 10.1038/nm1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimokawa C, et al. Mast cells are crucial for induction of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and clearance of helminth infections. Immunity. 2017;46:863–874 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Moltke J, Ji M, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Tuft-cell-derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2-epithelial response circuit. Nature. 2016;529:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature16161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howitt MR, et al. Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science. 2016;351:1329–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerbe F, et al. Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature. 2016;529:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature16527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voehringer D. Protective and pathological roles of mast cells and basophils. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:362–375. doi: 10.1038/nri3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan H, et al. Der p 1 facilitates transepithelial allergen delivery by disruption of tight junctions. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:123–133. doi: 10.1172/JCI5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asokananthan N, et al. House dust mite allergens induce proinflammatory cytokines from respiratory epithelial cells: the cysteine protease allergen, Der p 1, activates protease-activated receptor (PAR)-2 and inactivates PAR-1. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4572–4578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miike S, McWilliam AS, Kita H. Trypsin induces activation and inflammatory mediator release from human eosinophils through protease-activated receptor-2. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6615–6622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kouzaki H, O’Grady SM, Lawrence CB, Kita H. Proteases induce production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by airway epithelial cells through protease-activated receptor-2. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1427–1434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenbarth SC, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1645–1651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piggott DA, et al. MyD88-dependent induction of allergic Th2 responses to intranasal antigen. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:459–467. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun-Fahrlander C, et al. Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:869–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito T, Yamamoto T, Kazawa T, Gejyo H, Naito M. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 and 4 in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mouse. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;321:75–88. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berndt A, et al. Elevated amount of Toll-like receptor 4 mRNA in bronchial epithelial cells is associated with airway inflammation in horses with recurrent airway obstruction. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007;292:L936–L943. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammad H, et al. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat. Med. 2009;15:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willart MA, et al. Interleukin-1alpha controls allergic sensitization to inhaled house dust mite via the epithelial release of GM-CSF and IL-33. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1505–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibiza S, et al. Glial-cell-derived neuroregulators control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and gut defence. Nature. 2016;535:440–443. doi: 10.1038/nature18644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabanyi I, et al. Neuro-immune interactions drive tissue programming in intestinal macrophages. Cell. 2016;164:378–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller PA, et al. Crosstalk between muscularis macrophages and enteric neurons regulates gastrointestinal motility. Cell. 2014;158:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cardoso V, et al. Neuronal regulation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells via neuromedin U. Nature. 2017;549:277–281. doi: 10.1038/nature23469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klose CSN, et al. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2017;549:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature23676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriyama S, et al. beta2-adrenergic receptor-mediated negative regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses. Science. 2018;359:1056–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu J, Paul WE. Peripheral CD4+ T-cell differentiation regulated by networks of cytokines and transcription factors. Immunol. Rev. 2010;238:247–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010;28:445–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimoda K, et al. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–633. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan MH, Schindler U, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ. Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity. 1996;4:313–319. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takeda K, et al. Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signalling. Nature. 1996;380:627–630. doi: 10.1038/380627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammad H, et al. Inflammatory dendritic cells—not basophils—are necessary and sufficient for induction of Th2 immunity to inhaled house dust mite allergen. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2097–2111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phythian-Adams AT, et al. CD11c depletion severely disrupts Th2 induction and development in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2089–2096. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Rijt LS, et al. In vivo depletion of lung CD11c+ dendritic cells during allergen challenge abrogates the characteristic features of asthma. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:981–991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harada Y, et al. The 3′ enhancer CNS2 is a critical regulator of interleukin-4-mediated humoral immunity in follicular helper T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vijayanand P, et al. Interleukin-4 production by follicular helper T cells requires the conserved Il4 enhancer hypersensitivity site V. Immunity. 2012;36:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ballesteros-Tato A, et al. Follicular Helper Cell Plasticity Shapes Pathogenic T Helper 2 Cell-Mediated Immunity to Inhaled House Dust Mite. Immunity. 2016;44:259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coquet JM, et al. Interleukin-21-producing CD4(+) T cells promote type 2 immunity to house dust mites. Immunity. 2015;43:318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamaguchi Y, et al. Purified interleukin 5 supports the terminal differentiation and proliferation of murine eosinophilic precursors. J. Exp. Med. 1988;167:43–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hogan SP, Koskinen A, Matthaei KI, Young IG, Foster PS. Interleukin-5-producing CD4+ T cells play a pivotal role in aeroallergen-induced eosinophilia, bronchial hyperreactivity, and lung damage in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1998;157:210–218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9702074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu Z, et al. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:779–788. doi: 10.1172/JCI5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fort MM, et al. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15:985–995. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartemes KR, Kephart GM, Fox SJ, Kita H. Enhanced innate type 2 immune response in peripheral blood from patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;134:671–678 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walford HH, et al. Increased ILC2s in the eosinophilic nasal polyp endotype are associated with corticosteroid responsiveness. Clin. Immunol. 2014;155:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miljkovic D, et al. Association between group 2 innate lymphoid cells enrichment, nasal polyps and allergy in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2014;69:1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/all.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ho J, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) are increased in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps or eosinophilia. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2015;45:394–403. doi: 10.1111/cea.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu J. T helper 2 (Th2) cell differentiation, type 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) development and regulation of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 production. Cytokine. 2015;75:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang HC, et al. Downregulation of E protein activity augments an ILC2 differentiation program in the thymus. J. Immunol. 2017;198:3149–3156. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bando JK, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Identification and distribution of developing innate lymphoid cells in the fetal mouse intestine. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:153–160. doi: 10.1038/ni.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim AI, et al. Systemic human ILC precursors provide a substrate for tissue ILC differentiation. Cell. 2017;168:1086–1100 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Halim TY, et al. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoyler T, et al. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37:634–648. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wong SH, et al. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yokota Y, et al. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yagi R, et al. The transcription factor GATA3 is critical for the development of all IL-7Ralpha-expressing innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;40:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klose CS, et al. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klein Wolterink RG, et al. Essential, dose-dependent role for the transcription factor Gata3 in the development of IL-5+ and IL-13+ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:10240–10245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217158110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mjosberg J, et al. The transcription factor GATA3 is essential for the function of human type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barlow JL, et al. IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in provoking IL-13-producing nuocytes (type 2 innate lymphoid cells) and airway contraction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Salimi M, et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2939–2950. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim BS, et al. TSLP elicits IL-33-independent innate lymphoid cell responses to promote skin inflammation. Sci. Trans. Med. 2013;5:170ra16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bouchery T, et al. ILC2s and T cells cooperate to ensure maintenance of M2 macrophages for lung immunity against hookworms. Nat. Commu. 2015;6:6970. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roediger B, et al. IL-2 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function during pulmonary inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:1653–1663 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Motomura Y, et al. Basophil-derived interleukin-4 controls the function of natural helper cells, a member of ILC2s, in lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:758–771. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oliphant C. J., et al. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity41, 283–295 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Wilhelm C, et al. An IL-9 fate reporter demonstrates the induction of an innate IL-9 response in lung inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ni.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turner JE, et al. IL-9-mediated survival of type 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes damage control in helminth-induced lung inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2951–2965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Monticelli LA, et al. IL-33 promotes an innate immune pathway of intestinal tissue protection dependent on amphiregulin-EGFR interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10762–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Monticelli LA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1045–1054. doi: 10.1038/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wallrapp A, et al. The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung inflammation. Nature. 2017;549:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature24029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xue L, et al. Prostaglandin D2 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells through chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.von Moltke J, et al. Leukotrienes provide an NFAT-dependent signal that synergizes with IL-33 to activate ILC2s. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meylan F, et al. The TNF-family cytokine TL1A promotes allergic immunopathology through group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:958–968. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Serafini N, et al. Gata3 drives development of RORgammat + group 3 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:199–208. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhong C, et al. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells continuously require the transcription factor GATA-3 after commitment. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:169–178. doi: 10.1038/ni.3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bernink JH, et al. Interleukin-12 and -23 control plasticity of CD127(+) group 1 and group 3 innate lymphoid cells in the intestinal lamina propria. Immunity. 2015;43:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cella M, Otero K, Colonna M. Expansion of human NK-22 cells with IL-7, IL-2, and IL-1beta reveals intrinsic functional plasticity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10961–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005641107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klose CS, et al. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORgammat + innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhu J. Mysterious ILC2 tissue adaptation. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:1042–1044. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, et al. Tissue signals imprint ILC2 identity with anticipatory function. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:1093–1099. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huang Y, et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:161–169. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang K, et al. Cutting edge: notch signaling promotes the plasticity of group-2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Immunol. 2017;198:1798–1803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cai T, et al. IL-17-producing ST2(+) group 2 innate lymphoid cells play a pathogenic role in lung inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019;143:229–244 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Califano D, et al. Transcription factor Bcl11b controls identity and function of mature type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2015;43:354–368. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Spooner CJ, et al. Specification of type 2 innate lymphocytes by the transcriptional determinant Gfi1. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:1229–1236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lim AI, et al. IL-12 drives functional plasticity of human group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:569–583. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ohne Y, et al. IL-1 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function and plasticity. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:646–655. doi: 10.1038/ni.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Silver JS, et al. Inflammatory triggers associated with exacerbations of COPD orchestrate plasticity of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:626–635. doi: 10.1038/ni.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li BWS, et al. T cells and ILC2s are major effector cells in influenza-induced exacerbation of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019;49:144–156. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Van Dyken SJ, et al. A tissue checkpoint regulates type 2 immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1381–1387. doi: 10.1038/ni.3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shih HY, et al. Developmental acquisition of regulomes underlies innate lymphoid cell functionality. Cell. 2016;165:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shih HY, et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic networks of helper T and innate lymphoid cells. Immunol. Rev. 2014;261:23–49. doi: 10.1111/imr.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fang D, Zhu J. Dynamic balance between master transcription factors determines the fates and functions of CD4 T cell and innate lymphoid cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:1861–1876. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhu J. GATA3 regulates the development and functions of innate lymphoid cell subsets at multiple stages. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1571. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang Q, et al. TCF-1 upregulation identifies early innate lymphoid progenitors in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:1044–1050. doi: 10.1038/ni.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yu Y, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies a PD-1hi ILC progenitor and defines its development pathway. Nature. 2016;539:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 1986;136:2348–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gasteiger G, Fan X, Dikiy S, Lee SY, Rudensky AY. Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Science. 2015;350:981–985. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Huang Y, et al. S1P-dependent interorgan trafficking of group 2 innate lymphoid cells supports host defense. Science. 2018;359:114–119. doi: 10.1126/science.aam5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Martinez-Gonzalez I, et al. Allergen-experienced group 2 innate lymphoid cells acquire memory-like properties and enhance allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2016;45:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Maazi H, et al. ICOS:ICOS-ligand interaction is required for type 2 innate lymphoid cell function, homeostasis, and induction of airway hyperreactivity. Immunity. 2015;42:538–551. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Coyle AJ, et al. The CD28-related molecule ICOS is required for effective T cell-dependent immune responses. Immunity. 2000;13:95–105. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nurieva RI, et al. Transcriptional regulation of th2 differentiation by inducible costimulator. Immunity. 2003;18:801–811. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gonzalo JA, et al. ICOS is critical for T helper cell-mediated lung mucosal inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:597–604. doi: 10.1038/89739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wei G, et al. Genome-wide analyses of transcription factor GATA3-mediated gene regulation in distinct T cell types. Immunity. 2011;35:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fang D, et al. Bcl11b, a novel GATA3-interacting protein, suppresses Th1 while limiting Th2 cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1449–1462. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mueller SN, Gebhardt T, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Memory T cell subsets, migration patterns, and tissue residence. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Berard M, Tough DF. Qualitative differences between naive and memory T cells. Immunology. 2002;106:127–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Guo L, et al. IL-1 family members and STAT activators induce cytokine production by Th2, Th17, and Th1 cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13463–13468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906988106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Guo L, et al. Innate immunological function of TH2 cells in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:1051–1059. doi: 10.1038/ni.3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhang DH, Cohn L, Ray P, Bottomly K, Ray A. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in murine Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J. Bio Chem. 1997;272:21597–21603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Endo Y, et al. The interleukin-33-p38 kinase axis confers memory T helper 2 cell pathogenicity in the airway. Immunity. 2015;42:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jain A, Song R, Wakeland EK, Pasare C. T cell-intrinsic IL-1R signaling licenses effector cytokine production by memory CD4 T cells. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3185. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Halim TY, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mirchandani AS, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells drive CD4+ Th2 cell responses. J. Immunol. 2014;192:2442–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Drake LY, Iijima K, Kita H. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4+ T cells cooperate to mediate type 2 immune response in mice. Allergy. 2014;69:1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/all.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Halim TY, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells license dendritic cells to potentiate memory TH2 cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ni.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Liu B, Lee JB, Chen CY, Hershey GK, Wang YH. Collaborative interactions between type 2 innate lymphoid cells and antigen-specific CD4+ Th2 cells exacerbate murine allergic airway diseases with prominent eosinophilia. J. Immunol. 2015;194:3583–3593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Halim TYF, et al. Tissue-restricted adaptive type 2 immunity is orchestrated by expression of the costimulatory molecule OX40L on group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2018;48:1195–1207 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Freeman GJ, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Latchman Y, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Schwartz C, et al. ILC2s regulate adaptive Th2 cell functions via PD-L1 checkpoint control. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:2507–2521. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.McAdam AJ, et al. Mouse inducible costimulatory molecule (ICOS) expression is enhanced by CD28 costimulation and regulates differentiation of CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:5035–5040. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]