Abstract

Background

Despite improvements in diagnosis and patient management, survival and prognostic factors of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) remains largely unknown in most of Sub Saharan Africa.

Objective

To establish survival and associated factors among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma treated at Mulago Hospital Complex, Kampala.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study among histologically confirmed oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients seen at our centre from January 1st 2002 to December 31st 2011. Survival was analysed using Kaplan-Meier method and comparison between associated variables made using Log rank-test. Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine independent predictors of survival. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 384 patients (229 males and 155 females) were included in this analysis. The overall mean age was 55.2 (SD 4.1) years. The 384 patients studied contributed a total of 399.17 person-years of follow-up. 111 deaths were observed, giving an overall death rate of 27.81 per 100 person-years [95% CI; 22.97–32.65]. The two-year and five-year survival rates were 43.6% (135/384) and 20.7% (50/384), respectively. Tumours arising from the lip had the best five-year survival rate (100%), while tumours arising from the floor of the mouth, alveolus and the gingiva had the worst prognosis with five-year survival rates of 0%, 0% and 15.9%, respectively. Independent predictors of survival were clinical stage (p = 0.001), poorly differentiated histo-pathological grade (p < 0.001), male gender (p = 0.001), age > 55 years at time of diagnosis (p = 0.02) and moderately differentiated histo-pathological grade (p = 0.027). However, tobacco & alcohol consumption, tumour location and treatment group were not associated with survival (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

The five-year survival rate of OSCC was poor at 20.7%. Male gender, late clinical stage at presentation, poor histo-pathological types and advanced age were independent prognostic factors of survival. Early detection through screening and prompt treatment could improve survival.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Uganda, Survival, Clinical-pathological presentation

Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a potentially disfiguring and debilitating disease that affects the physical appearance of patients and devastates their self-esteem. Globally, over 175,000 cases are diagnosed annually [1]. The age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates of OSCC increases with age and are greater in males than females [2]. It is well established that tobacco use and alcohol consumption are significant risk factors [3]. Some studies suggest that among people living with HIV, the risk of oral cancer is elevated [4].

The risk factors for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) positive OSCC are mainly related to sexual habits rather than to tobacco and alcohol use in HPV negative OSCC [5]. Furthermore, over the past decade, oncogenic HPV type 16 has been linked to the development of some oral pharyngeal cancers but the association with oral cancer proper was not evident [6]. The detection of HPV DNA in some oral pharyngeal cancers has been linked to a favourable prognosis particularly among males [7]. Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) having a high burden of infection related cancers may provide unique circumstances in oral cancers worth researching.

Despite improvements in diagnostic facilities and patient management, survival and prognostic factors of OSCC remain unknown in most of SSA. Data from the Kampala Cancer Registry showed that oral cancer (ICD-10 C00-C06) was a rare disease that contributed 1.1% cases in Uganda [8]. However, there is paucity of data on survival and prognostic factors of oral cancers in Uganda. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to establish survival rates and determine independent prognostic factors of survival among patients with OSCC.

Methods

Study design and setting

Records of patients with histologically confirmed OSCC seen at Mulago Hospital Complex from January 1st 2002 to December 31st 2011 were reviewed.

Mulago hospital is a national referral hospital, which has the only functional oral and maxillofacial surgery unit and the only radiotherapy unit serving the whole of Uganda and the neighbouring countries. Additionally, Mulago Hospital Complex shares location with the Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) that provides chemotherapy treatment and care of cancer patients in Uganda and neighbouring countries. Records of patients with OSCC were retrieved from the Oral and Maxillofacial department and their socio-demographic, clinical and pathological data was abstracted. At both UCI and the Radiotherapy department, registers were used to identify patients with OSCC. Records of patients with OSCC were then retrieved and their details recorded.

Study population

The sample size was determined using the following assumptions: the log rank comparisons of the probability of experiencing death in 5 years between patients with early disease and those with advanced disease at 0.47, power of 80%, 5% significance level, an effect size of 1.595 and adjusting for loss to follow-up of 10%. The total number of (events) deaths that were required was 149 and at least 270 participants were required for this study.

Consecutive records of 384 index patients with a histological diagnosis of OSCC seen at Mulago Hospital Complex were retrieved for assessment. Records with missing important variables (e.g. date of diagnosis, site of lesion) or those with vague histological diagnosis (such as ‘moderately-well’ differentiated, ‘poorly-well’ differentiated), those of patients who presented with second primaries and patients who were referred to Hospice Uganda for terminal care, were excluded from the study. To eliminate duplicate recruits, patient demographic characteristics at different entry points of care were compared using hospital identification numbers and patient details. From each eligible record, demographic characteristics, pre-operative tumour characteristics, TNM stage, tobacco and alcohol usage, treatment instituted, length of follow-up and survival status were abstracted. To determine the nodal status in TNM staging, both clinical and radiological findings were assessed whenever available, while the evaluation of metastases was based on chest x-ray reports. In some cases, follow-up phone calls were made to patients or their next of kin with recorded telephone contacts in order to ascertain the status of the patient.

Statistics and analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA Version 12. The length of follow-up was defined as the period in months between the date of histological diagnosis and time to death or censoring. Cases were classified as alive, dead (if date of death was recorded) or lost to follow-up (date of last visit as recorded in patient’s file). Baseline characteristics for the patients were described using percentages for categorical variables and medians for continuous variables.

Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier analysis and the significance of the difference between survival curves for each variable was determined using the Breslow-test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to obtain independent predictors of survival. Construction of the final model was done in stages. Initially, all variables with a p value < 0.25 at univariate analysis were included in the multivariable model. To test for goodness of fit of the multivariable model a plot of Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate against Cox Snell residuals was plotted.

Results

Records of 512 patients were retrieved. One hundred twenty eight (25.0%) records were excluded due to missing data including: vague or no histological diagnosis, patients with second primaries, and patients referred to Hospice Uganda for terminal care. Therefore, 384 (75.0%) records were included in the analysis. In addition, 70 (13.7%) records with no data on clinical stage at presentation were excluded from survival analysis.

Socio-demographic characteristics, alcohol consumption and tobacco use

The mean age of the 384 patients included in this study was 55.2 years with a standard deviation of 4.1 years. There were 229 (59.6%) males and 155 (40.4%) females. Males had a mean age of 55.8 years (SD = 19.9 years), whereas females had a mean age of 55.6 years (SD = 15.9 years). Most patients were in their sixth decade 104 (27.1%). Most patients came from the western region of the country 130 (33.9%). Of the 214 patients with a history of education background, less than 40% had attained secondary level education (Table 1). Compared to females, more males reported use of tobacco and alcohol.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and pathological characteristics of 384 OSCC patients

| Characteristic | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 229(59.6) |

| Female | 155(40.4) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 55.2(4.1) |

| Tobacco use | |

| User | 147(54.7) |

| Non-User | 122(45.4) |

| Alcohol use | |

| User | 140(52.6) |

| Non-User | 126(47.4) |

| Geographical region | |

| Central | 132(34.4) |

| Eastern | 72(18.7) |

| Northern | 41(10.7) |

| Western | 109(28.4) |

| Non-Ugandan | 30(7.8) |

| Education level | |

| Tertiary | 27(12.6) |

| Secondary | 44(20.6) |

| Primary | 68(31.8) |

| None | 75(35.0) |

| Histo-pathological grade | |

| Well differentiated | 198(51.5) |

| Moderately differentiated | 102(26.6) |

| Poorly differentiated | 84(21.9) |

| Treatment modality | |

| Surgery | 38(9.9) |

| Radiotherapy | 224(58.3) |

| Chemotherapy | 4(1.0) |

| Surgery + Radiotherapy | 41(10.7) |

| Surgery + Chemotherapy | 8(2.1) |

| Surgery + Radiotherapy +Chemotherapy | 8(2.1) |

| Radiotherapy + Chemotherapy | 3(0.8) |

| None | 58(15.1) |

Sub-site tumour presentation, histopathological grading and clinical stage

The distribution of primary tumour sites, spread and clinical stage of OSCC is presented in Table 2. In descending order, the tongue (34.1%), palate (13.5%), buccal mucosa (13.3%) and floor of the mouth (12.2%) were the commonest primary sites.

Table 2.

Sub-site distribution, TNM classification and clinical stage at presentation of 384 patients with OSCC

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Site | ||

| Alveolus | 18 | 4.7 |

| Buccal Mucosa | 51 | 13.3 |

| Floor of mouth | 47 | 12.2 |

| Gingiva | 43 | 11.2 |

| Lip | 16 | 4.2 |

| Palate | 52 | 13.5 |

| Tongue | 131 | 34.1 |

| Otherα | 26 | 6.8 |

| T (Tumour) | ||

| 1 | 41 | 10.7 |

| 2 | 142 | 37.0 |

| 3 | 91 | 23.7 |

| 4 | 62 | 16.1 |

| X | 48 | 12.5 |

| N (Nodal involvement) | ||

| 0 | 151 | 39.3 |

| 1 | 63 | 16.5 |

| 2 | 106 | 27.6 |

| 3 | 22 | 5.7 |

| X | 42 | 10.9 |

| M (Metastasis) | ||

| 0 | 228 | 59.4 |

| 1 | 86 | 22.4 |

| X | 70 | 18.2 |

| Clinical Stage (Based on TNM staging system) | ||

| I | 23 | 6.0 |

| II | 57 | 14.8 |

| III | 148 | 38.5 |

| IV | 86 | 22.5 |

| X | 70 | 18.2 |

αOther includes Commissure, Buccal sulcus, Retromolar trigone, Sublingual salivary glands

X Missing data

Majority 51.6% (n = 198) of patients had well differentiated tumours, and about one-fifth (21.9%, n = 84) had poorly differentiated tumours. Majority (61%) of the identified OSCC were in TNM stage III and IV (Table 1).

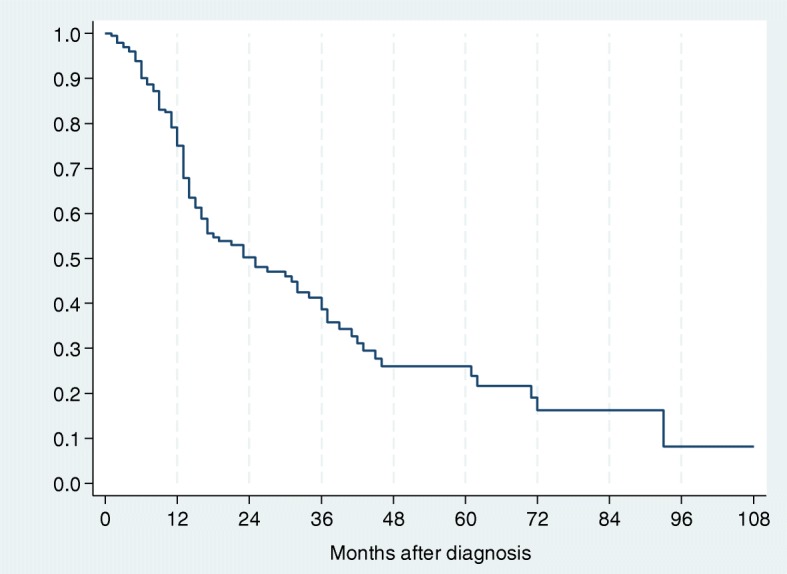

Survival pattern of 384 patients with OSCC

The 384 patients studied contributed a total of 399.17 person–years of follow-up. One hundred eleven deaths were observed, giving an overall death rate of 27.81 per 100 person–years [95% CI; 22.97–32.65]. The overall average survival time for patients with OSCC was 375 days. The two-year and five-year survival rates were respectively 43.6% (135/384) and 20.7% (50/384), (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survival Pattern of 384 patients with OSCC

| Time (years) | Total number | Deaths | Censored | Survival | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 384 | 50 | 199 | 0.824 | 0.775 0.864 |

| 1 | 135 | 40 | 45 | 0.531 | 0.450 0.606 |

| 2 | 50 | 8 | 11 | 0.436 | 0.347 0.521 |

| 3 | 31 | 10 | 6 | 0.280 | 0.189 0.378 |

| 4 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0.280 | 0.189 0.378 |

| 5 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 0.207 | 0.117 0.314 |

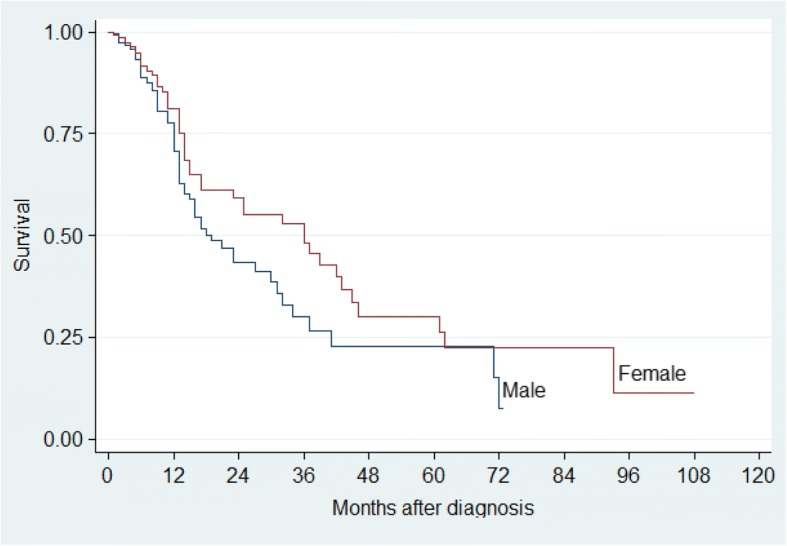

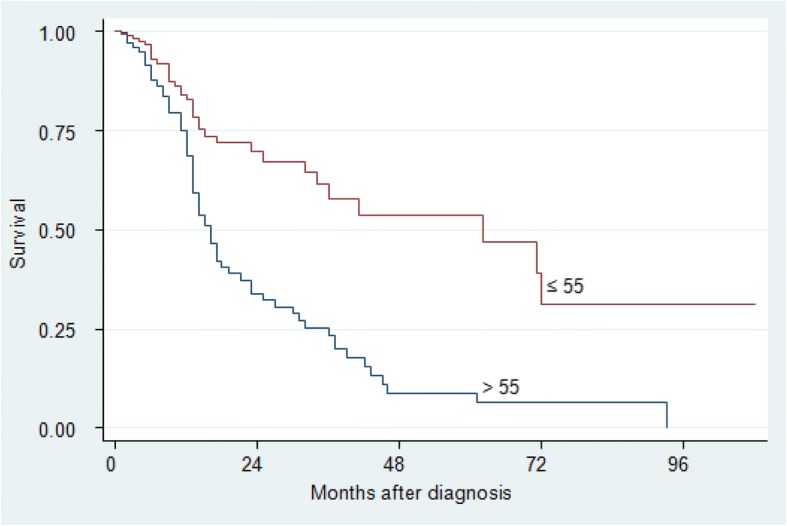

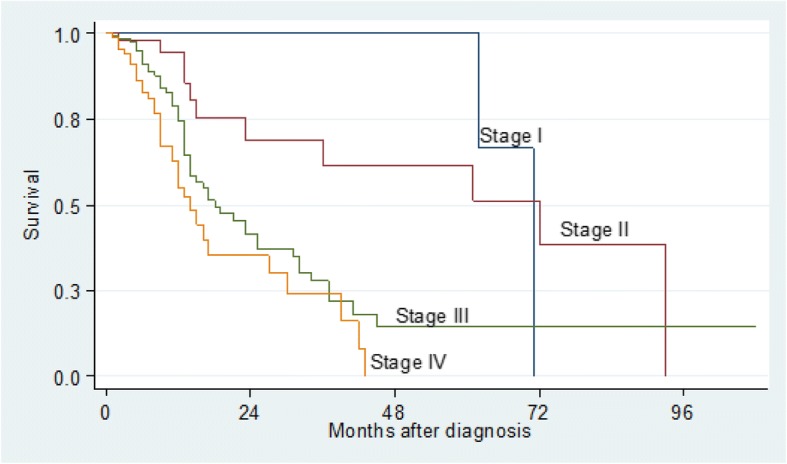

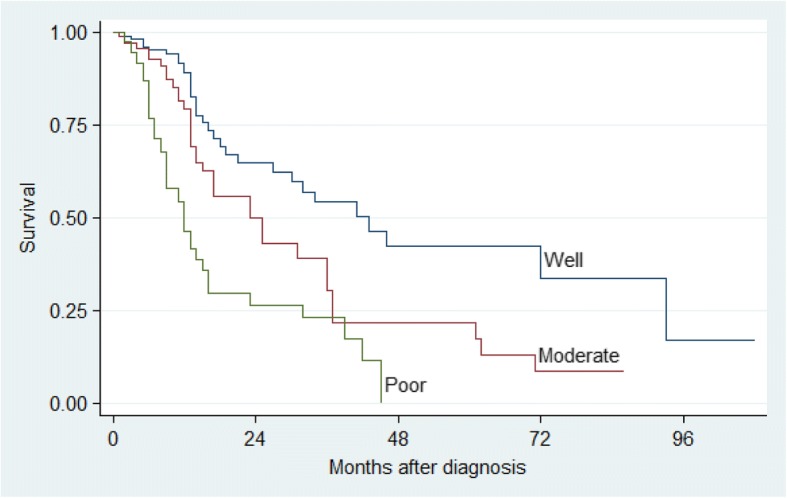

The two-year and five-year survival rates were significant for age (p = 0.001), clinical stage (p < 0.001) and pathological stage (p < 0.001). There was no difference in gender, tumour localisation, treatment group and in patients with or without a history of either tobacco or alcohol consumption (p > 0.05), (Table 4). Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test were used for bivariate analysis. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed for all patients and for significant variables (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of 384 Patients with OSCC

| Variable | Survival rate (%) | P value (log-rank) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-year | 5-year | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 43.3 | 22.9 | 0.053 |

| Female | 59.2 | 30.1 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤ 55 | 69.7 | 53.7 | 0.001 |

| > 55 | 34.0 | 8.8 | |

| Tobacco Use | |||

| User | 47.7 | 15.8 | 0.091 |

| Non-User | 49.6 | 29.8 | |

| Alcohol Use | |||

| User | 46.6 | 26.3 | 0.460 |

| Non-User | 50.7 | 21.0 | |

| Tumour Location | |||

| Alveolus | 59.3 | 0.0 | 0.255 |

| Buccal mucosa | 47.0 | 19.6 | |

| Floor of mouth | 34.5 | 0.0 | |

| Gingiva | 39.7 | 15.9 | |

| Lip | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Palate | 52.3 | 43.6 | |

| Tongue | 53.3 | 21.2 | |

| Other | 53.9 | 53.9 | |

| Clinical Stage | |||

| I | 100.0 | 100.0 | < 0.001 |

| II | 69.1 | 61.5 | |

| III | 41.7 | 14.5 | |

| IV | 35.4 | 0.0 | |

| Histo-pathological grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 64.9 | 42.2 | < 0.001 |

| Moderately differentiated | 50.1 | 21.7 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 26.4 | 0.0 | |

| Treatment Group | |||

| Surgery | 73.8 | 61.5 | 0.103 |

| Radiotherapy | 47.5 | 27.6 | |

| Chemotherapy | 100.0 | 0.0 | |

| At least 2 | 55.3 | 12.3 | |

Other – Commissure, Buccal sulcus, Retromolar trigone, Sublingual salivary glands

At least 2 – Surgery and Radiotherapy or Surgery and Chemotherapy

P value is for 5-year survival

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for 384 patients with OSCC

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates by Gender for patients with OSCC

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates by Age for patients with OSCC

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates by Clinical Stage for patients with OSCC

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates by Histo-pathological Grade for patients with OSCC

Predictors of survival among OSCC patients

Construction of the final model containing variables found to be independently associated with survival of oral cancer was made using Cox proportional hazards model. A model which included all variables that had a P–value of less than 0.25 at univariate analysis was formed (Table 5). These included clinical stage, pathological variant, treatment group, gender, age and tobacco use. The variable tumour site (p = 0.26) was included on the basis of previous studies.

Table 5.

Model showing the combined effect of significant variables

| Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I & II | 1 | |||

| III & IV | 2.998 | 1.584 | 5.674 | 0.001 |

| Histo-pathological grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 1 | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 1.756 | 1.065 | 2.897 | 0.027 |

| Poorly differentiated | 2.985 | 1.798 | 4.957 | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 55 | 1 | |||

| > 55 | 1.022 | 1.008 | 1.036 | 0.002 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.482 | 0.310 | 0.749 | 0.001 |

The model was tested to verify whether the assumption of proportionality between early-stage and late stage disease patient categories. The proportionality of hazards assumption of the model was tested as a whole, and for each variable using the global test and the extended Cox model. The model was not significant based on the Schoenfeld’s test (p = 0.838) and the extended Cox model indicating that the data did not violate the proportional hazards assumption. There model was tested for interaction and confounding, using clinical stage as the main predictor of survival. The final model was thus determined as:

The model itself was significant (p < 0.001). It was also tested for goodness of fit using a plot of Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate against Cox Snell residuals which gave a good model.

Assessment of selection bias on participants lost to follow-up

A total of 141 (44.9%) participants were lost to follow-up during the study. This rate is higher than the acceptable 15%. The characteristics of these patients were assessed to determine the possibility of selection bias. The patients who were lost to follow-up had similar characteristics to those who remained in the study except with reference to treatment group, as shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Comparison of characteristics of patients enrolled and those lost to follow-up

| Variable | Alive/Dead | Lost to follow-up | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 173) | % | Total (n = 141) | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 105 | 60.7 | 81 | 57.4 | 0.560 |

| Female | 68 | 39.3 | 60 | 42.6 | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 56 | (44.5–66) | 60 | (47.5–66) | 0.284 |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| User | 79 | 51.6 | 68 | 58.6 | 0.254 |

| Non-user | 74 | 48.4 | 48 | 41.4 | |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| User | 85 | 55.9 | 55 | 48.2 | 0.215 |

| Non-user | 67 | 44.1 | 59 | 51.8 | |

| Tumour location | |||||

| Alveolus | 6 | 3.6 | 10 | 7.1 | 0.764 |

| Buccal mucosa | 17 | 9.8 | 18 | 12.8 | |

| Floor of mouth | 22 | 12.7 | 13 | 9.2 | |

| Gingiva | 23 | 13.3 | 15 | 10.6 | |

| Lip | 7 | 4.0 | 9 | 6.4 | |

| Palate | 24 | 13.9 | 21 | 14.9 | |

| Tongue | 62 | 35.8 | 47 | 33.3 | |

| Other | 12 | 6.9 | 8 | 5.7 | |

| Clinical stage | |||||

| I | 16 | 9.2 | 7 | 5.0 | 0.410 |

| II | 31 | 17.9 | 26 | 18.4 | |

| III | 79 | 45.7 | 69 | 48.9 | |

| IV | 47 | 27.2 | 39 | 27.7 | |

| Histo-pathological grade | |||||

| Well differentiated | 80 | 45.8 | 89 | 63.1 | 9.351 |

| Moderately differentiated | 46 | 26.8 | 32 | 22.7 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 47 | 27.4 | 20 | 14.2 | |

| Treatment group | |||||

| Surgery | 18 | 11.8 | 17 | 15.0 | 0.057 |

| Radiotherapy | 110 | 71.9 | 72 | 63.7 | |

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| At least 2 | 23 | 15 | 23 | 20.4 | |

Discussion

This study, to the best of our knowledge presents one of a few on survival of OSCC patients in Sub Saharan Africa. It showed poor survival of patients with OSCC (20.7%) after five years and almost half of them (43.6%) had died within 2 years of diagnosis. Our findings are similar to the low five-year survival rate observed in Egypt for intra oral cancers (20.8%) [9]. However, better survival especially for stages III and IV has been reported in resource rich countries like Taiwan 26.6% and 11.8% [10], Brazil 32.6% and 24.5% [11] and the USA [12]. This discrepancy may be a reflection of better screening programs for early detection of cases and better treatment modalities, which ultimately improves survival, in the better resourced countries. The case for standardised treatment and its effect on survival irrespective of the difference in ethnicity and economic status has already been made for all head and neck squamous cell carcinomas [13].

Gender had a significant effect on survival in our study with the risk of death two times greater in males compared to females (Table 5 and Fig. 2). The effect of gender on survival remains mixed and unclear. Whereas some studies suggest a greater survival for females [14, 15], Mehta et al. reported lesser improvement in survival for females with oral cavity and oral pharyngeal carcinomas [16]. Other studies have reported no significant difference in survival between males and females [10]. It is believed that more males than females are affected by OSCC and have worse survival because of their increased exposure to tobacco and alcohol [2]. Furthermore, the males have poor health seeking behaviours, which may translate into delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation [17].

Age was a significant prognostic factor for survival in this study (Table 5 and Fig. 3). Patients who presented with OSCC and were above 55 years had a significantly shorter survival time as compared to those who were younger (p = 0.001). Our findings are consistent with studies conducted in Brazil [11], USA [16], Taiwan [10] and Egypt [9]. There seems to be a general agreement that the lower survival among older patients may be related to the higher rates of co-morbidities associated with ageing. It is also possible that these co-morbidities preclude the older patients from long surgical interventions which disadvantages their survival yet radiotherapy alone has been reported to lead to worse prognosis [11, 18]. In addition, with the emerging role of HPV, in oral and oral pharyngeal cancers, it may be that the younger population has a different causative factor hence better outcomes. However, a study from Mbarara in western Uganda showed a low prevalence of HPV among the head and neck cancers [19].

Education level, alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking were not significant predictors of survival. However, determination of cigarette smoking and tobacco and alcohol use, post event, may not be accurate thus making determination of their influence on patient survival hard to establish [20]. Education level is a surrogate for socio-economic status which has been shown to affect survival. Therefore, more research needs to be done to establish why it had no effect in our study.

Tumour site was not an independent predictor of survival. This was consistent with other studies [21] but different from others [9, 11, 14]. The possibility of misclassification of original OSCC site is high given the complex anatomy of the oral cavity coupled with delayed presentation seen among our patients [22]. In advanced stages, there could be an overlap of oral tumours that arise from adjacent structures leading to misclassification. In this study, about two-thirds of patients presented with late stage disease making misclassification of the original site of OSCC highly likely.

OSCC arising from the lip had the best five-year survival rate (100%) consistent with results from other studies [9, 14]. This may be because lip cancer is noticed earlier by patients and so they tend to seek care earlier. On the other hand, the floor of the mouth, alveolus and the gingiva had the worst five-year survival rates of 0%, 0% and 15.9%, respectively. Our results are different from those obtained from other studies which showed that the tongue had the lowest survival rate [11, 12]. The differences in survival by tumour site could arise from the ease of early diagnosis, accessibility for excision of the tumour with sufficient surgical margin and the different lymph node involvement that each site presents. However, given the previously reported late presentation among our patients [22], tongue carcinomas may progress into the floor of the mouth making it hard to know the original site. In addition, some anatomic sites manifest greater metastatic capacity due to high lymphatic drainage [17].

We found an inverse relationship between tumour stage and survival (p < 0.001), which was consistent with other studies [9, 11, 18, 21, 23]. The five-year survival rates were 100%, 61.5%, 14.5% and 0% for patients with stages I, II, III and IV, respectively. A study conducted in Egypt found similar survival rates of 100%, 65.5%, 42.2% and 0% for stages I, II, III and IV disease, respectively [9]. However, the rates in our study are much lower than those reported by two studies that investigated the outcomes of OSCC after surgical and/or radiation therapy in America [24] and Taiwan [21]. The much lower survival rates reported in this study could be a reflection of the study population that comprised more of patients in clinical stages III and IV than those in stages I and II at presentation, which was much higher than those reported by other studies.

Histo-pathological grading was a significant predictor of survival in this study. It is widely reported that prognosis is better with early stage well differentiated disease than other histo-pathological types [21]. In fact, the risk of death increased with less well differentiated tumours in this study. Patients with poorly and moderately differentiated tumours had three fold and almost two fold risk of death, respectively, compared to those who had well differentiated tumours. However, it is worth noting that some reports have not shown tumour grade to have an effect on survival [11, 23].

The type of treatment received by the patient was not a predictor of survival in this study. Of the 384 patients, about two-thirds (67.3%) received at least one form of treatment (Table 3). Radiotherapy, either alone or in combination with surgery was the most common treatment modality. Patients treated with surgery showed the highest two-year and five-year survival rates followed by surgery and radiotherapy. However, most untreated patients died within 5 years and so did many of the patients treated with radiotherapy alone or chemotherapy alone. However, several studies where surgery was the primary mode of treatment found treatment modality as a significant predictor of survival [10–12, 21]. The treatment modality is dependent on stage of disease and other parameters such as anatomical site, tumour size, distant metastasis, histological type and lymph node involvement [12]. While surgery alone may be recommended for patients with early stage disease, adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy is indicated for patients with advanced stages [12].

The large number of patients lost to follow up could also explain why treatment modality was not a significant predictor of survival since patients who were lost to follow-up had a borderline difference (p = 0.057) from those who were not, with respect to treatment group. Patients who were lost to follow-up were most likely those who were assigned to treatment modalities that required repeated visits such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy for advanced stage disease. It is also possible that many of the patients lost to follow-up were travelling long distances to access these treatment modalities, which would make re-visits expensive. Furthermore, patients were classified solely on their treatment status without taking into consideration the dosage, duration and compliance with treatment received. In our setting sometimes surgery is not an option due limited surgical space. Sometimes this may lead to significant delays in accessing the service thus disease progression and change in stage [25]. This does have a significant effect on outcomes. It is not any different when it comes to radiotherapy were machine breakdowns and patient load likewise lead to delayed treatment compromising outcomes [26].

Limitations

Our study was a hospital and not population-based study. It may therefore not be a representative sample of all the OSCC in Uganda. Data on HIV status of the patients and detection of HPV DNA in the tumours was not available. Seventy (13.7%) records with no data on clinical stage at presentation were excluded from survival analysis. However, this did not affect the power of the study given that we sampled 384 records, compared to 270 required for this study.

Conclusion

Poor survival rates of oral cancer were recorded in this study, with two-year and five-year survival rates at 43.6% and 20.7% respectively. Male gender, late clinical stage at presentation due to delay in seeking medical care, poor histo-pathological types and advanced age were independent predictors of survival. Early detection through screening and prompt treatment could improve survival.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Professor Charles Karamagi (PhD) and Ass Prof Joan Kalyango (PhD) of the Clinical Epidemiology Unit, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University Kampala Uganda, for mentoring JA and for their invaluable input during the study.

Funding

This study was personally funded.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- EBV

Epstein barr virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPV

Human Papilloma Virus

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- HSSP

Health sector strategic plan

- IQR

Inter-quartile range

- LTC

Lymphoma treatment centre

- MoH

Ministry of Health

- NCD

Non-communicable disease

- OSCC

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- SD

Standard deviation

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STC

Solid tumour treatment centre

- TNM

Tumour node metastasis

- UCI

Uganda Cancer Institute

- WHO

World Health Organisation

Authors’ contributions

JA contributed to the conception and design of the study, collected data, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the manuscript. CB participated in the design of the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. AK interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have given their final approval of the version to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. (Protocol number 3/SOMEREC/14/12). Consent waiver was sought for abstracting information from patients’ records.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juliet Asio, Email: julietasio@yahoo.com.

Adriane Kamulegeya, Email: adrianek55@yahoo.com.

Cecily Banura, Email: cecily.banura@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert R, Sauvaget C, de Camargo Cancela M, Sankaranarayanan R. Epidemiology of cancer from the oral cavity and oropharynx. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:633–641. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283484795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson N. Tobacco use and Oral Cancer: a global perspective. J Dent Educ. 1991;65:328–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH, Hall HI, Li J, Chaturvedi AK, et al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:753–762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Termine N, Panzarella V, Falaschini S, Russo A, Matranga D, Muzio LL, et al. HPV in oral squamous cell carcinoma vs head and neck squamous cell carcinoma biopsies : a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1681–1690. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz SR, Yueh B, Mcdougall JK, Daling JR, Schwartz SM. Human papillomavirus infection and survival in oral squamous cell cancer:a population based study. Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:1–9. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.116979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus – positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, Okello C, Mbus L, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala Uganda 1991-2010. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:432–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim NK, Al Ashakar MS, Gad ZM, Warda MH, Ghanem H. An epidemiological study on survival of oropharyngeal cancer cases in Alexandria, Egypt. East Mediterr Heal J. 2009;15:369–377. doi: 10.26719/2009.15.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YK, Huang HC, Lin LM, Lin CC. Primary oral squamous cell carcinoma: an analysis of 703 cases in southern Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:173–179. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leite ICG, Koifman S. Survival analysis in a sample of oral cancer patients at a reference hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Funk GF, Robinson RA, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:951–962. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.9.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen LM, Li G, Reitzel LR, Pytynia KB, Zafereo ME, Wei Q, et al. Matched-pair analysis of race or ethnicity in outcomes of head and neck Cancer patients receiving similar multidisciplinary care. [Phila Pa] Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:782–791. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boing AF, Peres MA, Antunes JLF. Mortality from oral and pharyngeal cancer in Brazil : trends and regional patterns , 1979 – 2002. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;20:1–8. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892006000700001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook MB, Mcglynn KA, Devesa SS, Freedman ND, Anderson WF. Sex disparities in Cancer mortality and survival. Canncer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;20:1–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta V, Yu G, Schantz SP. Population-based analysis of Oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: changing trends of histopathologic differentiation , survival and patient demographics. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2203–2212. doi: 10.1002/lary.21129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massano J, Regateiro SF, Januario G, Ferreira A. Oral squamous cell carcinoma : review of prognostic and predictive factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris LGT, Ganly I. Outcomes of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma in pediatric patients. Oral Oncol. 2011;46:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabukenya J, Hadlock TA, Arubaku W. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Western Uganda: disease of uncertainty and poor prognosis. Oto Open. 2018;1:7. doi: 10.1177/2473974X18761868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen AJ, Moran PJ, Ehlers SL, Raichle K, Karnell L, Funk G. Smoking and drinking behavior in patients with head and neck Cancer: effects of behavioral self-blame and perceived control. J Behav Med. 1999;22:407–408. doi: 10.1023/A:1018669222706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo W, Kao S, Chi L, Wong Y, Chang CR. Outcomes of Oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan after surgical therapy: factors affecting survival. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:751–758. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kakande E, Byaruhaga R, Kamulegeya A. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a Ugandan population: a descriptive epidemiological study. J Afr Cancer. 2010;2:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s12558-010-0116-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantola S, Parikka M, Jokinen K, Hyrynkangs K, Soini Y, Alho OP, et al. Prognostic factors in tongue cancer - relative importance of demographic, clinical and histopathological factors. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:614–619. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulte D, Brenner H. Changes in survival in head and neck cancers in the late 20th and early 21st century: a period analysis. Oncologist. 2010;15:994–1001. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajja I, Sibinga CTS. Delayed elective surgery in a major teaching hospital in Uganda. Int J Clin Transfus Med. 2014;2:1–6. doi: 10.2147/IJCTM.S59616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kigula MJB, Wegoye P. Pattern and experience with cancers treated with the chinese GWGP80 cobalt unit at Mulago hospital, Kampala. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:523–525. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i10.46705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.