Abstract

To assess the use of plasma free amino acids (PFAAs) as biomarkers for metabolic disorders, it is essential to identify genetic factors that influence PFAA concentrations. PFAA concentrations were absolutely quantified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry using plasma samples from 1338 Japanese individuals, and genome-wide quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis was performed for the concentrations of 21 PFAAs. We next conducted a conditional QTL analysis using the concentration of each PFAA adjusted by the other 20 PFAAs as covariates to elucidate genetic determinants that influence PFAA concentrations. We identified eight genes that showed a significant association with PFAA concentrations, of which two, SLC7A2 and PKD1L2, were identified. SLC7A2 was associated with the plasma levels of arginine and ornithine, and PKD1L2 with the level of glycine. The significant associations of these two genes were revealed in the conditional QTL analysis, but a significant association between serine and the CPS1 gene disappeared when glycine was used as a covariate. We demonstrated that conditional QTL analysis is useful for determining the metabolic pathways predominantly used for PFAA metabolism. Our findings will help elucidate the physiological roles of genetic components that control the metabolism of amino acids.

Subject terms: Genome-wide association studies, Metabolomics

Introduction

Circulating metabolite concentrations in the body can serve as useful biomarkers for the diagnosis, prognosis, and risk assessment of diseases, particularly for metabolic disorders such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension [1–8]. Among these metabolites, the free amino acids in plasma (PFAAs) are key regulators of metabolic pathways, and their concentrations are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, such as the diet [9–14].

Recently, several genome-wide association studies (GWAS) also identified genetic variations associated with PFAAs in European populations [9–11, 13, 15]. However, the influence of heritability and whether these loci are shared among other human populations are still unknown. In addition, metabolite concentrations are influenced by other metabolites within the same metabolic pathway. Therefore, genome-wide quantitative trait locus (QTL) analyses conditioned on the other amino acids sharing the same pathway are necessary.

In this study, we sought to elucidate genetic determinants that influence PFAA concentrations. We conducted a QTL analysis of PFAAs measured by an absolute quantification method using plasma samples from 1338 Japanese individuals.

Materials and methods

Subjects and ethics

Participants were recruited from the Nagahama Prospective Genome Cohort for Comprehensive Human Bioscience (the Nagahama Study). All of the subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board and the ethics committees of each institute, to which donors gave written informed consent, in accordance with the national guidelines.

Absolute quantification of PFAA concentrations

The concentrations of 21 PFAAs from 2,084 individuals who participated in the Nagahama study in 2008 (n = 1124) and 2009 (n = 960) were quantified. Blood samples (5 ml) were collected from forearm veins after overnight fasting into tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Termo, Tokyo, Japan). The plasma was extracted by centrifugation at 2010×g at 4 °C for 15 min and then stored at –80 °C. After deproteinizing the thawed plasma samples using 80% acetonitrile, the samples were subjected to pre-column derivatization, then the absolute concentrations, the absolute concentrations of the PFAAs were measured by high performance liquid chromatography - electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC–ESI–MS). The methods were previously developed and verified by the authors [16–19].

Quantification was considered successful when the obtained value was within the determination range of the calibration curve.

PFAA concentrations for QTL analysis

For the QTL analysis, we prepared three adjusted PFAA concentrations from the measured absolute concentrations of PFAAs. The first adjusted concentration was adjusted for sex and age by linear regression after Box-Cox transformation. The second was adjusted by the other 20 PFAAs by multiple linear regression after the first adjustment. For this regression analysis, explanatory variables were selected by the step-wise function (stepwiseglm) in MATLAB, with P = 0.001 and P = 0.01 as inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively. The third was adjusted by one of the other PFAAs by linear regression after the first adjustment.

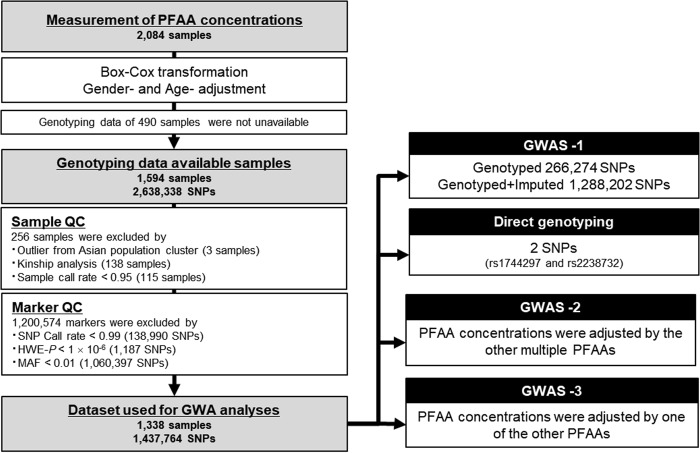

SNP genotyping and quality control (QC) process

A total of 1594 samples were genotyped using three commercially available Illumina genotyping arrays (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA): Human610-Quad BeadChip (610 K), HumanOmni-2.5-Quad BeadChip (2.5M-4), and HumanOmni-2.5-8 BeadChip (2.5M-8). The 1,124 subjects recruited in 2008 were genotyped using 610 K (n = 1,113) or both 610 K and 2.5M-4 (n = 11). The 470 subjects recruited in 2009 were genotyped using 610 K (n = 101), 2.5M-4 (n = 293), 2.5M-8 (n = 62), or both 610 K and 2.5M-4 (n = 14). In total, 2,638,338 SNPs were genotyped in the arrays. As shown in Fig. 1, through a sample QC process, 256 samples were excluded from the analysis: 3 genetic outliers identified by principal component analysis (PCA), 138 relatives, and 115 samples with a call rate of SNPs < 0.95. Through a marker QC process, 1,200,574 SNPs were excluded: 138,990 SNPs with a call rate < 0.99, 1,187 SNPs with deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P < 1.0 × 10–6), and 1,060,397 SNPs with a variant allele frequency < 1%. After the QC processes, 1,437,764 SNPs in 1338 samples remained for the GWA studies. Of these, 266,274 SNPs shared among all of the arrays were defined as intersectional SNPs. All of the QC procedures were processed using PLINK ver. 1.07 [20]. Both genotype and PFAA concentrations data of Nagahama study is deposited on the Japanese Genotype-phenotype Archive affiliated to the DDBJ (DNA Data Bank of Japan), via National Bioscience DataBase (NBDC), Japan. The data is accessible on hum0012 at https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/viewer/permit/dataset/JGAD00000000012.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the QC processes and QTL analyses using the PFAA concentrations of Japanese subjects from the Nagahama Study

Imputation

The 1,437,764 SNPs from 1,338 samples used for the GWA studies were imputed using MACH ver. 1.0 [21]. An imputation panel was generated using the genotyping data of 665 Nagahama Study samples that were not used for the present GWA analyses and contained the results of 1,560,699 SNPs with Illumina HumanCoreExome BeadChip (Exome), HumanOmni2.5 S BeadChip (2.5 S), 2.5M-4, and 2.5M-8 arrays. Of these 665 samples, 478 were genotyped using all of the arrays, and 187 were genotyped using the Exome, 2.5 S, and 2.5M-4. Imputed SNPs with a variant allele frequency > 1% or an r2 < 0.5 were excluded from the subsequent association analysis. Finally, 1,288,202 SNPs from the 1338 samples were fixed with 1,021,918 additional SNPs.

QTL analysis

For the three PFAA concentrations described above, QTL analysis was conducted with a an additive model implemented in PLINK [2.0]. The genome-wide significance threshold after Bonferroni correction was P < 3.88 × 10–8.

Direct genotyping

The direct genotyping of two imputed SNPs (rs1744297 and rs2238732) was performed with TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays using the ABI PRISM 7700 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The genotyping success rates were 98.7% (1917/1942) and 98.6% (1915/1942) for rs1744297 and rs2238732, respectively.

In silico analysis of genetic variants

The exome sequencing data of 300 Japanese individuals from the Human Genetic Variation Database (HGVD) were used to identify candidates for genetic variants with a functional impact on PFAA concentrations [22, 23]. Pair-wise linkage disequilibrium (LD) coefficients (r2) were calculated using PLINK [20]. The impacts of the non-synonymous variants were predicted using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor [24], which is based on the SIFT [25] and PolyPhen [26] algorithms. Expression QTL (eQTL) analysis data (release version 8.0) were also downloaded from the HGVD [22].

Results

PFAA profiling

We measured the PFAA concentrations by an absolute quantification method using HPLC–ESI–MS [16–19]. The concentrations of 21 PFAAs were quantified successively in all of the samples (N = 2,094). The PFAA concentrations in the 1,338 samples used for GWAS are summarized with biochemical parameters in Table 1. The means, standard deviations, and ranges of the absolute concentrations were comparable to those obtained in an independent study in a Japanese population, except for arginine, glutamate, and ornithine [27]. The averaged levels of glutamate and ornithine higher, and that of arginine was lower, than in the previous study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and PFAA concentrations of the 1,338 subjects in this study

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1338 | |

| Women | 873 (62.5%) | |

| Current smoker | 256 (18.3%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (4.5%) | |

| Prevalent cardiovascular disease | 49 (3.7%) | |

| Prevalent cancer | 48 (3.4%) | |

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Age, years | 49.8 (14.6) | 30–75 |

| Body-mass index, kg/cm2 | 22.1 (3.2) | 14–41 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127.6 (17.4) | 84–230 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80.1 (11.1) | 50–138 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 92.1 (22.2) | 68–572 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.38 (0.60) | 4.23–14.22 |

| Insulin, μIU/mL | 6.15 (7.70) | 0.77–118.00 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 203.0 (34.9) | 86–338 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 65.0 (16.6) | 27–122 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 120.4 (31.4) | 26–240 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 95.4 (68.0) | 21–930 |

| Free fatty acid, mEq/L | 0.73 (0.29) | 0.14–2.11 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 7.3 (0.4) | 5.9–9.5 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.5 (0.2) | 3.0–5.2 |

| Amino acids, µM | ||

| alanine (Ala) | 319.3 (71.0) | 169.5–646.4 |

| alpha-amino-butyric acid (a-ABA) | 16.4 (5.1) | 4.2–59.9 |

| arginine (Arg) | 63.2 (18.2) | 13.6–174.5 |

| asparagine (Asn) | 45.7 (8.0) | 26.3–93.4 |

| citrulline (Cit) | 31.0 (8.2) | 9.9–110.3 |

| glutamate (Glu) | 53.2 (19.3) | 19.1–176.9 |

| glutamine (Gln) | 541.6 (69.2) | 185.6–757.7 |

| glycine (Gly) | 225.6 (64.4) | 90.7–717.9 |

| histidine (His) | 77.8 (10.1) | 49.0–220.3 |

| isoleucine (Ile) | 56.5 (13.7) | 24.0–119.9 |

| leucine (Leu) | 111.2 (23.0) | 58.2–198.9 |

| lysine (Lys) | 171.5 (32.7) | 84.7–326.4 |

| methionine (Met) | 21.9 (4.7) | 11.5–60.3 |

| ornithine (Orn) | 82.8 (22.1) | 31.3–181.8 |

| phenylalanine (Phe) | 54.5 (8.5) | 34.3–95.9 |

| proline (Pro) | 133.5 (45.7) | 53.7–559.9 |

| serine (Ser) | 112.7 (21.9) | 42.0–215.2 |

| threonine (Thr) | 115.1 (28.1) | 54.5–287.9 |

| tryptophan (Trp) | 50.1 (8.8) | 27.2–81.9 |

| tyrosine (Tyr) | 56.8 (11.9) | 27.1–130.9 |

| valine (Val) | 200.8 (41.0) | 110.5–366.9 |

QTL analysis of PFAAs (GWAS-1)

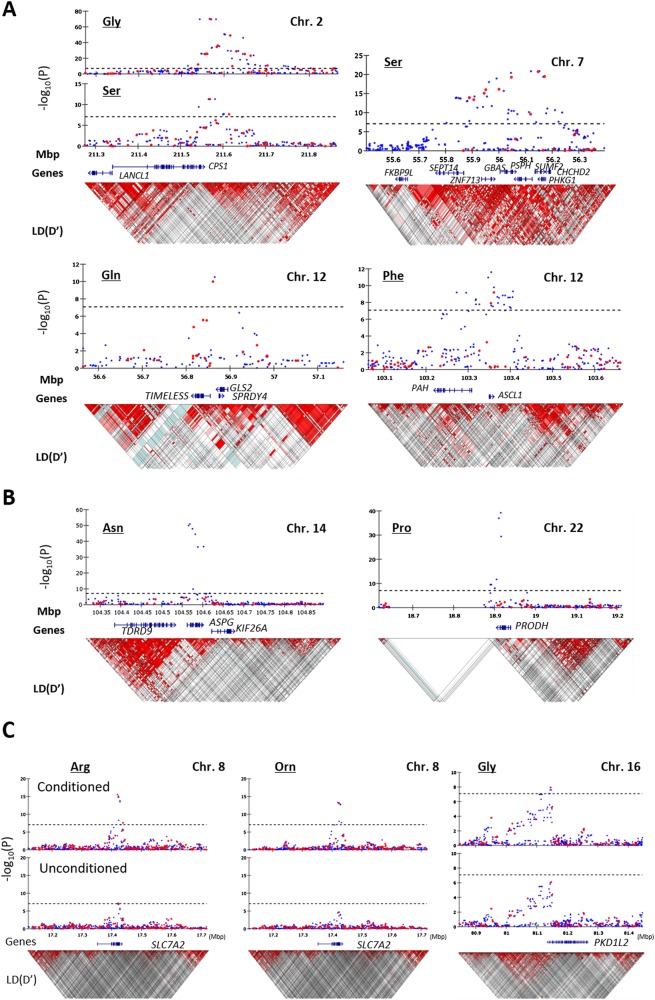

A flow diagram of the QC processes and QTL analyses is shown in Fig. 1. The first QTL analysis was conducted for each PFAA concentration, which was adjusted for sex and age after Box-Cox transformation, with 266,274 intersectional SNPs of 1338 samples (GWAS-1). Twenty-eight SNPs in four loci were significantly associated with glycine, serine, glutamine, and phenylalanine (Fig. 2a and Table 2). The strongest association was observed in the CPS1 locus on chromosome 2 for the glycine concentration (rs12613336, P = 2.07 × 10–70). CPS1 encodes mitochondrial carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1 (CPS-I), a key enzyme in the urea cycle, which generates carbamoyl-phosphate from H2O, CO2, and ammonia. Two chromosomal loci showing significant associations with the serine concentration were identified: the PSPH locus on chromosome 7 (rs13244654, P = 1.80 ×10–21) and the CPS1 locus, which was also associated with the glycine concentration (rs12613336, P = 4.77 × 10–12). PSPH encodes phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH), which catalyzes the hydrolysis of 3-phosphoserine to generate serine. In addition, the GLS2 locus and the PAH locus on chromosome 12 were associated with the concentration of glutamine (rs7302925, P = 9.73 × 10–11), and phenylalanine (rs17450273, P = 6.60 × 10–10), respectively. GLS2 encodes glutaminase, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of glutamine to glutamate and ammonia, and PAH encodes phenylalanine hydroxylase.

Fig. 2.

Regional association plots of the six loci significantly associated with PFAA concentrations (n = 1338). a Association was significantly identified from genotyped data. b Association was significantly identified after imputation. Chromosomal positions and P values for genotyped SNPs (red) and imputed SNPs (blue) are shown. c Chromosomal positions and P values for genotyped SNPs (red) and imputed SNPs (blue) of the conditional (upper) and unconditional (lower) analyses are shown. Dotted lines indicate the genome-wide significance threshold after Bonferroni correction. Brightness of the red color in the linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks corresponds to the strength of LD

Table 2.

Genetic variants associated with PFAAs in Japanese

| Trait | Locus | SNP ID | Chr.a | Position | Beta (SEb) | r 2 | P value | Ref. (A1) / Var. (A2). | Freq. (A1) | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS-1 | ||||||||||

| Gly | CPS1 | rs12613336 | 2 | 211,569,399 | 0.90 (0.05) | 0.21 | 2.07 × 10–70 | T/C | 0.90 | Intergenic |

| Ser | CPS1 | rs12613336 | 2 | 211,569,399 | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.04 | 4.77 × 10–12 | T/C | 0.90 | Intergenic |

| Ser | PSPH | rs13244654 | 7 | 56,146,956 | −0.36 (0.04) | 0.07 | 1.80 × 10–21 | T/C | 0.90 | Intronic |

| Gln | GLS2 | rs7302925 | 12 | 56,861,458 | −0.39 (0.06) | 0.03 | 9.73 × 10–11 | A/G | 0.85 | Upstream |

| Phe | PAH | rs17450273 | 12 | 103,361,379 | 0.35 (0.06) | 0.03 | 6.60 × 10–10 | C/A | 0.69 | Intergenic |

| Asn | ASPG c | rs1744297 | 14 | 104,568,472 | 0.82 (0.05) | 0.16 | 1.30 × 10–51 | T/C | 0.87 | Intronic |

| Pro | PRODH c | rs2238732 | 22 | 18,915,347 | 0.69 (0.05) | 0.12 | 5.96 × 10–40 | C/T | 0.87 | Intronic |

| GWAS-2 | ||||||||||

| Arg | SLC7A2 | rs56335308 | 8 | 17,419,461 | −0.43 (0.05) | 0.05 | 2.64 × 10–16 | G/A | 0.93 | Exonic, Non-synonymous |

| Orn | SLC7A2 | rs56335308 | 8 | 17,419,461 | −0.35 (0.05) | 0.04 | 4.70 × 10–14 | G/A | 0.93 | Exonic, Non-synonymous |

| Gly | PKD1L2 | rs8059153 | 16 | 81,145,675 | −0.21 (0.04) | 0.02 | 1.46 × 10–8 | T/C | 0.93 | Intronic |

achromosome

bstandard error

cimputation was performed using the genotyping results of 665 samples that were unrelated to those used for the present study

Next, we performed imputation using the genotyping results of 665 samples that were unrelated to those used for the present GWA study. The additional imputed genotypes of 1,021,928 SNPs were used for the QTL analysis. We identified two additional chromosomal loci in which multiple SNP markers showed a significant association with PFAA concentrations (Fig. 2b and Table 2): the ASPG (putative asparaginase) locus on chromosome 14 for asparagine (rs1744297, P = 1.30 × 10–51) and the PRODH (proline dehydrogenase) locus on chromosome 22 for proline (rs2238732, P = 5.96 × 10–40). To confirm these associations, these two SNPs were genotyped for the same DNA samples using the Taqman assay (Table 3). We obtained P = 2.36 × 10–48 for rs1744297 and P = 5.78 × 10–36 for rs2238732, and the concordance rates between the imputed and directly genotyped SNPs were 98.6% (1300/1319) and 97.6% (1289/1321) for rs1744297 and rs2238732, respectively.

Table 3.

Direct genotyping assay of ASPG and PRODH loci

| Locus (rs ID) | Genotyped samples | Validation samples | Combined data set | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta(SEa) | r 2 | P value | N | Beta(SEa) | r 2 | P value | N | Beta(SEa) | r 2 | P value | N | |

| ASPG (rs1744297) | 0.79 (0.05) | 0.15 | 2.36 × 10–48 | 1319 | 0.83 (0.07) | 0.19 | 2.40 × 10–28 | 598 | 0.81 (0.04) | 0.16 | 1.04 × 10–74 | 1917 |

| PRODH (rs2238732) | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.11 | 5.78 × 10–36 | 1321 | 0.67 (0.07) | 0.14 | 1.21 × 10–20 | 594 | 0.65 (0.04) | 0.12 | 2.33 × 10–54 | 1915 |

astandard error

The imputation analysis identified six additional chromosomal loci with potential associations. However, only one SNP marker showed a significant association for each locus, so no further analysis was performed. The 151 SNPs showing significant associations either by genotyping or by imputation are listed in Table S1.

QTL analysis of PFAAs conditioned on the other amino acids (GWAS-2)

We next conducted QTL analysis using the concentration of each PFAA adjusted using the other 20 PFAAs as covariates (GWAS-2 in Fig. 1). The optimal regression models for each PFAA were constructed using a step-wise variable selection method (Table S2). Two additional association loci were identified by the conditional QTL analysis (Fig. 2c and Table 2). The strongest association was observed at a non-synonymous variant, rs56335308, in the SLC7A2 (a solute carrier family 7, cationic amino acid transporter) gene on chromosome 8 for arginine (P = 2.64 × 10–16) and ornithine (P = 4.70 × 10–14). The other was the PKD1L2 locus on chromosome 16 for glycine (rs8059153, P = 1.46 × 10–8). This gene encodes a member of the polycystin protein family. In addition, an association was found between rs2238732 in the PRODH locus and the alanine concentration (P = 7.10 × 10–11). On the other hand, the significant association between serine and the CPS1 locus disappeared (P = 0.63). The other six associations maintained significant levels after the conditional analysis. The 209 SNPs identified as significant in GWAS-2 are listed in Table S3.

QTL analysis of PFAAs adjusted conditioned on one of the other amino acids (GWAS-3)

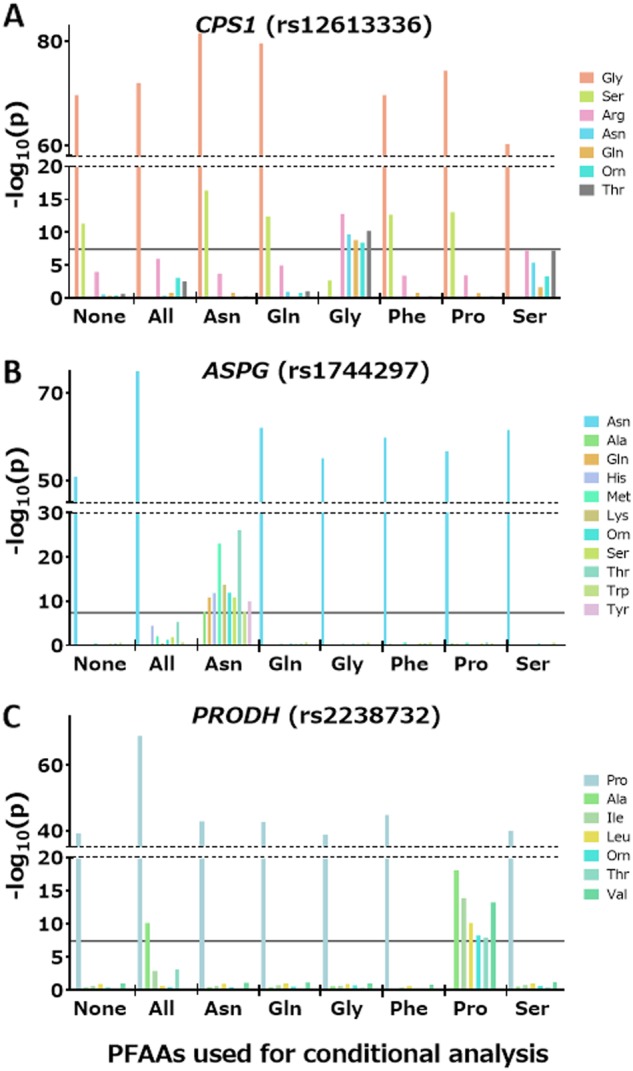

We also conducted QTL analyses of 21 PFAAs conditioned on one of the six PFAAs (asparagine, glutamine, glycine, phenylalanine, proline, and serine) identified as significant in the above studies (GWAS-3 in Fig. 1). The significant association between serine and the CPS1 locus disappeared when glycine was used for the adjustment (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, significant associations between five PFAAs (arginine, asparagine, glutamine, ornithine, and threonine) and the CPS1 locus were still apparent when glycine was used as a covariate (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Strength of the associations of three loci (CPS1, ASPG, and PRODH) conditioned on other PFAA concentrations. P values for the SNPs conditioned on other PFAA concentrations are plotted as bars

When asparagine was used as a covariate, rs1744297 in the ASPG locus showed additional associations with ten PFAAs: alanine, glutamine, histidine, lysine, methionine, ornithine, serine, threonine, tryptophan, and tyrosine (Fig. 3b). Rs2238732 in the PRODH locus also showed an association with seven PFAAs (alanine, isoleucine, leucine, ornithine, threonine, tyrosine, and valine) (Fig. 3c) using proline as a covariate. Similarly, significant associations were observed in PSPH for threonine using serine (P = 3.82 × 10–8) and in PAH for methionine using phenylalanine (P = 1.91 × 10–9) as a covariate. All of the statistics in GWAS-3 are listed in Table S4.

In silico analysis for the functional interpretation of the association between identified SNPs and PFAA concentrations

In the above analyses, three of the eight loci that showed significant associations, namely, rs56335308 in GLS2, rs2657879 in PRODH, and rs450046 in SLC7A2, were non-synonymous variations with potential functional effects on PFAA concentrations (Table S1). We tried to identify non-synonymous SNPs that were in strong LD with the SNPs showing significant associations within the eight loci in the above analysis, by conducting an in silico analysis using pair-wise LD information in the HGVD exome sequencing data set [23]. Among the 223 SNPs with LD coefficients (r2) greater than 0.8 with SNPs significantly associated with PFAAs, four non-synonymous variants were identified: rs1047891 in CPS1, rs8012505 in ASPG, rs8054182 in PKD1L2, and rs5747933 in PRODH (Table S5). The predicted functional impacts of these variants were not deleterious to the gene products except for ASPG. There were no non-synonymous variants for the PSPH or PAH gene.

We next investigated whether these SNPs within the eight loci identified in the current study or those that were in strong LD with them influenced gene expression using the HGVD expression QTL (eQTL) information [22]. We found that rs4948073, which was located approximately 240-kb downstream of the PSPH gene, showed the strongest association with the expression level of the PSPH gene (P = 3.03 × 10–46). There were no significant eQTLs for the other six loci.

Discussion

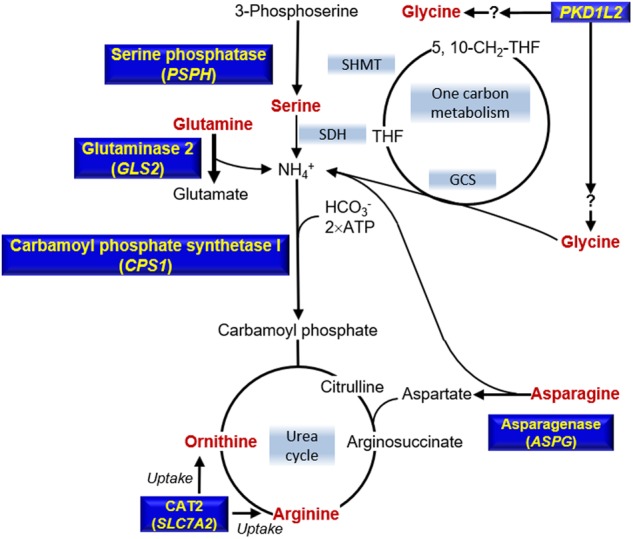

In this study, we conducted a QTL analysis of the absolute concentrations of PFAAs quantified by LC-MS technology. The concentration of a PFAA can be influenced by other PFAAs within the same metabolic pathway. Therefore, it is also important to perform conditional QTL analysis considering the amino acids’ metabolic pathways when identifying the genetic determinants of PFAA concentrations. Notably, here we identified two additional genetic loci associated with the concentrations of arginine, ornithine, and glycine (Table S2). One of the identified genes, SLC7A2 was associated with arginine and ornithine. This protein is known to transport plasma arginine into cells for protein synthesis and to convert arginine into ornithine or nitric oxide [28]. SLC7A family members, such as SLC7A5, SLC7A6, and SLC7A9, are associated with plasma tryptophan, lysine, and arginine, respectively [9, 13, 29, 30]. Thus, it is likely that genetic variations of SLC7A2 would affect the plasma concentration of arginine and ornithine. The other identified gene, PKD1L2, which showed an association with glycine concentration, encodes polycystic kidney disease protein 1-like 2. Previous studies suggested that genetic variation of the PKD1L2 gene may be associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [31, 32]. Rs8054182, which has strong LD with rs8059153 (r2 = 0.989), introduces an amino acid change from methionine to isoleucine at position 1630, which is in the conserved ion channel pore region [33]. It is therefore possible to speculate that PKD1L2 acts as part of a glycine transporter (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Metabolic pathways relevant to genotype-PFAA associations. The six PFAAs (red) were associated with genotypes in the genes (yellow). THF tetrahydrofuran, 5-CH3-THF 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, 5,10-CH2-THF 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofuran, NH4+ ammonium ion, GCS glycine cleavage system, SDH serine dehydratase, SHMT serine hydroxymethyltransferase

Significant associations of CPS1 with the plasma levels of arginine, asparagine, glutamine, ornithine, and threonine were observed only after being conditioned on glycine (Fig. 3a). Asparagine and glutamine syntheses have CPS-I in their upstream pathway (Fig. 4). Threonine is also involved in the ammonia-generating reaction mediated by L-serine dehydratase/L-threonine deaminase [34]. Both arginine and ornithine are involved in the urea cycle, which is the downstream pathway of CPS-I (Fig. 4). These mechanisms suggest that the plasma concentrations of these five PFAAs are influenced by the enzymatic activity of CPS-I. Similarly, associations exist for ASPG for ten PFAAs were obtained only after being conditioned on asparagine (Fig. 3b). Rs8012505, a non-synonymous SNP that has strong LD with rs1744297, is located at the provisional cytoplasmic asparaginase I (ansA) domain and changes serine to arginine at position 344. We speculate that ASPG can use these ten PFAAs as substrates for deamination. Similarly, significant associations of PRODH for seven PFAAs were obtained only after being conditioned on proline, suggesting that PRODH can use them as substrates (Fig. 3c). In some situations, use of heritable covariates might introduce unintended bias into estimate [35]. Direct enzymatic verification whether ASPG and PRODH can catalyze other amino acids than asparagine and proline, respectively, will be desirable to confirm our speculations.

We also demonstrated that the conditional QTL analysis is useful for determining the metabolic pathway predominantly used for PFAA metabolism. For example, the concentration of plasma glycine is correlated with that of serine (r = 0.54), and the significant association between serine and CPS1 in the unconditional QTL analysis disappeared when conditioned on glycine (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the significant association between glycine and CPS1 was not affected by the analysis conditioned on serine (Fig. 3a). CPS-I is considered an entrance to the urea cycle, which detoxifies the ammonia that is produced by amino acid degradation. Two separate pathways that generate ammonia are likely to be involved in this process. The first is the conversion of glycine to ammonia catalyzed by the glycine cleavage system (GCS) with tetrahydrofolate production [36]. The second is the conversion of serine to ammonia and pyruvate, which is catalyzed by serine dehydratase [37]. In addition, glycine and serine are reversibly converted to each other via serine hydroxymethyltransferase [38]. The study of hyperglycinemia, an inborn deficiency of GCS, revealed that GCS plays a critical role in both glycine and serine catabolism in the liver [36]. The results of the conditional QTL analysis in the present study were consistent with previous clinical observations.

It is still unknown whether common variants that influence the concentrations of plasma amino acids are associated with risks of lifestyle-related metabolic diseases. For example, although the plasma glycine concentration is associated with an increased risk of diabetes [7, 8, 39], no genetic variants that are significantly associated with a risk of diabetes have been identified within the CPS1 locus [12]. Further longitudinal studies with increased sample sizes are needed to assess whether the PFAA concentrations can be used as intermediate biomarkers for metabolic disease risk under a variety of genetic backgrounds.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the Center of Innovation Program from MEXT and JST. We thank the Non-profit Organization “Zero-ji Club for Health Promotion,” the staff and associates of the Nagahama City Office, Kohoku Medical Association, Nagahama City Hospital, Nagahama Red Cross Hospital, Nagahama Kohoku City Hospital, and the participants of the Nagahama Study, for data collection.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KH, YT, TS, MM, YN, NS, RY, FM. Data acquisition and quality control: TK, YT, KS, MT, TM, HY, NK, CO, MT, HM. Data analysis: AI, YA, TK, KH. Contributed materials/analysis tools: TK, KH, YT, KS, RY, FM. Wrote the paper: AI, YA, TK, KH, FM.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Akira Imaizumi, Phone: +81 44 210 5828, Email: akira_imaizumi@ajinomoto.com.

Fumihiko Matsuda, Phone: +81 75 751 4156, Email: fumi@genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-018-0296-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med. 2011;17:448–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah SH, Kraus WE, Newgard CB. Metabolomic profiling for the identification of novel biomarkers and mechanisms related to common cardiovascular diseases: form and function. Circulation. 2012;126:1110–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu F, Tavintharan S, Sum CF, et al. Metabolic signature shift in type 2 diabetes mellitus revealed by mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1060–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng S, Rhee EP, Larson MG, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies pathways associated with metabolic risk in humans. Circulation. 2012;125:2222–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9:311–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormack SE, Shaham O, McCarthy MA, et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang-Sattler R, Yu Z, Herder C, et al. Novel biomarkers for pre-diabetes identified by metabolomics. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:615. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamakado M, Nagao K, Imaizumi A, et al. Plasma free amino acid profiles predict 4-year risk of developing diabetes, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in Japanese population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11918. doi: 10.1038/srep11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin SY, Fauman EB, Petersen AK, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nat Genet. 2014;46:543–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Illig T, Gieger C, Zhai G, et al. A genome-wide perspective of genetic variation in human metabolism. Nat Genet. 2010;42:137–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suhre K, Gieger C. Genetic variation in metabolic phenotypes: study designs and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:759–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie W, Wood AR, Lyssenko V, et al. Genetic variants associated with glycine metabolism and their role in insulin sensitivity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:2141–50. doi: 10.2337/db12-0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee EP, Ho JE, Chen MH, et al. A genome-wide association study of the human metabolome in a community-based cohort. Cell Metab. 2013;18:130–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kettunen J, Tukiainen T, Sarin AP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci influencing human serum metabolite levels. Nat Genet. 2012;44:269–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mardinoglu A, Agren R, Kampf C, et al. Genome-scale metabolic modelling of hepatocytes reveals serine deficiency in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3083. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimbo K, Yahashi A, Hirayama K, Nakazawa M, Miyano H. Multifunctional and highly sensitive precolumn reagents for amino acids in liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5172–9. doi: 10.1021/ac900470w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimbo K, Oonuki T, Yahashi A, Hirayama K, Miyano H. Precolumn derivatization reagents for high-speed analysis of amines and amino acids in biological fluid using liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:1483–92. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimbo K, Kubo S, Harada Y, et al. Automated precolumn derivatization system for analyzing physiological amino acids by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009;24:683–91. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida H, Kondo K, Yamamoto H, et al. Validation of an analytical method for human plasma free amino acids by high-performance liquid chromatography ionization mass spectrometry using automated precolumn derivatization. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2015;998-999:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narahara M, Higasa K, Nakamura S, et al. Large-scale East-Asian eQTL mapping reveals novel candidate genes for LD mapping and the genomic landscape of transcriptional effects of sequence variants. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higasa K, Miyake N, Yoshimura J, et al. Human genetic variation database, a reference database of genetic variations in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:547–53. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–81. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto H, Kondo K, Tanaka T, et al. Reference intervals for plasma-free amino acid in a Japanese population. Ann Clin Biochem. 2015;53(Pt 3):357–64. doi: 10.1177/0004563215583360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fotiadis D, Kanai Y, Palacin M. The SLC3 and SLC7 families of amino acid transporters. Mol Asp Med. 2013;34:139–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaper T, Looger LL, Takanaga H, et al. Nanosensor detection of an immunoregulatory tryptophan influx/kynurenine efflux cycle. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verrey F, Closs EI, Wagner CA, et al. CATs and HATs: the SLC7 family of amino acid transporters. Pflug Arch. 2004;447:532–42. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dastani Z, Pajukanta P, Marcil M, et al. Fine mapping and association studies of a high-density lipoprotein cholesterol linkage region on chromosome 16 in French-Canadian subjects. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:342–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackenzie FE, Romero R, Williams D, et al. Upregulation of PKD1L2 provokes a complex neuromuscular disease in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3553–66. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li A, Tian X, Sung SW, Somlo S. Identification of two novel polycystic kidney disease-1-like genes in human and mouse genomes. Genomics. 2003;81:596–608. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogawa H, Gomi T, Fujioka M. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase and threonine aldolase: are they identical? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:289–301. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(99)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aschard H, Vilhjalmsson BJ, Joshi AD, Price AL, Kraft P. Adjusting for heritable covariates can bias effect estimates in genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:329–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kikuchi G, Motokawa Y, Yoshida T, Hiraga K. Glycine cleavage system: reaction mechanism, physiological significance, and hyperglycinemia. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2008;84:246–63. doi: 10.2183/pjab.84.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa H, Gomi T, Konishi K, et al. Human liver serine dehydratase. cDNA cloning and sequence homology with hydroxyamino acid dehydratases from other sources. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15818–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stover P, Schirch V. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase catalyzes the hydrolysis of 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate to 5-formyltetrahydrofolate. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Floegel A, Stefan N, Yu Z, et al. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes. 2013;62:639–48. doi: 10.2337/db12-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.