Abstract

Clinical Genetics services provide a diagnostic, counselling and genetic testing service for children and adults affected by, or at risk of, a genetic condition, most of which are rare, and/or genetically heterogeneous. Appropriate triage of referrals is crucial to ensure that the most urgent referrals are seen as quickly as possible, without negatively impacting the waiting times of less urgent cases. We aimed to examine triage practice in six Clinical Genetic centres across the United Kingdom and Ireland. Thirteen simulated referrals were drafted based on common referrals to Clinical Genetics. Copies of each referral were forwarded to each centre, where 10 nominated clinicians were asked to triage each referral. Triaged referrals were returned to the coordinating author for analysis. An electronic questionnaire was contemporaneously completed by clinical leads in each unit to gather local demographic details and local operating procedures relevant to triage. Widespread inconsistencies were noted both within and between units, with respect to the acceptance of referrals to the services, prioritisation and designated clinic type. Referral rates, staffing levels and waiting lists varied widely between units. Inconsistencies observed between units are likely influenced by a number of factors, including staffing levels, referral rates and average family size. Inconsistency within units likely reflects the complex nature of many Clinical Genetic referrals, and triage guidelines should help improve decision-making in this setting.

Subject terms: Genetic counselling, Preventive medicine, Genetic testing

Introduction

Clinical Genetics services provide a diagnostic, counselling and genetic testing service for children and adults affected by, or at risk of, a genetic condition [1]. Referrals come from almost all specialties, from primary, secondary and tertiary centres [2]. The geographical catchment area and indications for referral (from neonatal to adult; dysmorphology, and referrals from all subspecialties) covered by Clinical Genetics centres are wide.

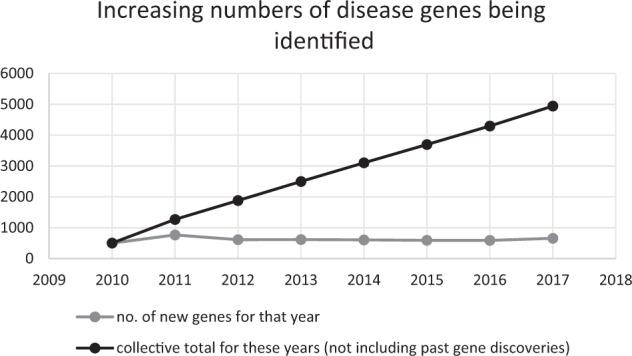

Increasingly broad genetic testing has led to the discovery of novel disease genes, and new genotype–phenotype associations (Fig. 1) [3]. This has positively impacted diagnostic yield in patients with disorders related to previously undefined genetic aetiology (e.g., epilepsy, sudden adult death); but has also led to increased detection of variants of uncertain significance [4, 5], and of variants in genes not previously known to be associated with a particular phenotype (“genes of uncertain significance”) [6]. Such variants generate massive clinical workload, and often require reviewing multiple family members to facilitate segregation analysis; or may require multiple patient encounters to facilitate collection of different sample types for functional studies (e.g., skin or muscle biopsy, biochemical testing). A single referral may therefore generate many days–weeks of clinical work. Furthermore, absolute numbers of referrals may be a poor reflection of the workload of a unit, depending on the complexity of the case mix [7]. Benign, likely benign or uncertain variants are frequently picked up by array CGH [8], a test routinely used by general paediatricians. As non-geneticists grapple with increasingly complex genetic test reports, they request advice to help interpret the report; while the actual presenting complaint in the patient may have been considered too trivial to refer in the past. Previous audits suggest referrals to explain normal benign or likely benign human variation accounting for 10% of general referrals [9].

Fig. 1.

Graph showing the rate of gene discovery and the cumulative total number of known disease genes

The specialty mainly receives non-urgent outpatient referrals; however, prenatal referrals, or referrals for patients approaching end of life require prompt assessment. Demand for urgent access to genetic testing is growing where the results might influence management. Increasingly, targeted therapies are being licenced for use in patients with germline or somatic genetic variation, particularly in treatment of cancer (e.g., PARP inhibitors, ATR inhibitors and small-molecule kinase inhibitors) [10, 11]. Public and media awareness has also driven demand, both of those affected or at risk of a familial genetic disorder [12]. Increasing cost efficiency of testing has led to an interest in population-based screening for genetic disorders [13–15], and has driven direct-to-consumer testing, with a predicted market value of up to $310 million by 2022 [16, 17]. Consequently, this puts increasing stress on under-resourced genetic services.

Genetic counsellors are highly skilled clinical professionals, usually from scientific or nursing backgrounds, with specialist training in genetic counselling [18]. Not all countries employ genetic counsellors, but they form a core part of the Clinical Genetics teams in the United Kingdom and Ireland [19]. In most genetic centres in the United Kingdom and Ireland, consultant geneticists review undiagnosed or complex patients, while genetic counsellors review patients at risk of a known familial genetic disorder, to offer pre-symptomatic predictive testing. Some centres utilise a co-counselling approach involving both types of professionals [19], while in other centres, patients have an initial “pre-clinic” with a genetic counsellor, followed thereafter by consultant-led interaction. It is well-recognised that there is a significant shortage of both genetic counsellors and consultant clinical geneticists internationally, particularly in Ireland and England [20–22]. Appropriate triage of referrals is a critical factor in trying to address demands on the service in the face of limited resources; to ensure that the most urgent referrals are seen as quickly as possible, without negatively impacting the waiting times of less urgent cases. To ensure optimal provision of services, the Clinical Genetics Society has considered a number of common referrals that do not need face-to-face consultation in a Clinical Genetics Centre [23]. Centres have also adopted local policies to reject referrals pertaining to conditions where specialist clinics exist in the region [24]. In Centre 1, for example, all referrals related to patients with inherited cardiac pathologies are deferred to the Cardiology service. In Centre 3, referrals related to common paediatric conditions such as Down syndrome or spina bifida are managed by letter to the patient, without offering the patient a formal consultation. This may partly explain interdepartmental differences.

However, as referrals may pertain to any one of thousands of different rare disorders, standardisation of referrals is very difficult. We aimed to review the practice of triage in Clinical Genetics centres in the United Kingdom and Ireland using high-fidelity simulated referrals.

Methods

A consultant geneticist in each centre was identified and asked to co-ordinate the study locally. Participants were asked to complete a short questionnaire to establish local demographics and local practice at their respective centre. Data were collected with respect to factors that could potentially influence triage practice, including staffing level, waiting lists, catchment area and population size, clinicians responsible for triage and number of referrals per year.

Thirteen simulated referrals were designed (by TMcV and SAL). Ten were based on genuine referrals, with a patient, referring doctor and hospital identifiers removed, and details modified so as to maintain confidentiality in line with European General Data Protection Regulation legislation. The remaining three (referral nos. 4, 7 and 13) were composed by the authors based on common referrals to a Clinical Genetics service. All were printed on headed notepaper of a fictitious hospital (Supplementary Figure 1), and 10 hard copies were posted to each centre. This was to endeavour to create high-fidelity simulated referrals with the expectation that the research triage would be a true reflection of genuine triage [25, 26]. The nature of the 13 referrals can be seen in Table 1. Participants were told that these were simulated referrals. We deliberately mis-spelt certain words, and inserted information regarding a patient’s pregnancy in the middle of a referral‚ rather than placing emphasis on the urgency of the referral, reflecting frequent errors in referrals from practitioners unfamiliar with genetic conditions and implications of such disorders for progeny of affected individuals, increasing fidelity of the simulation.

Table 1.

Table showing the referral reason for each case simulation and the consensus triage response

| Referral | Referral reason | Consensus (majority opinion) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Copy-number variant of uncertain significance in the child with developmental delay | Accept for routine, consultant, face-to-face appointment |

| 2 | Child with hypermobility | No appointment required (lack of consensus about reject/request more information) |

| 3 | Child with intermediate FMR1 allele | Accept for routine, consultant, face-to-face appointment |

| 4 | Trisomy 21 | Accept for routine, GC, face-to-face appointment |

| 5 | Adult with intellectual disability | Accept for routine, consultant, face-to-face appointment |

| 6 | Predictive BRCA testing (no information regarding familial variant provided) | Accept for priority, GC, face-to-face appointment |

| 7 | Young female with cervical cancer | No appointment required (lack of consensus about reject/request more information) |

| 8 | Isolated cleft lip | No consensus |

| 9 | Two family members with congenital heart disease (unspecified) | Accept for routine, consultant, face-to-face appointment |

| 10 | Pregnant woman with family history of Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Accept for priority, GC, face-to-face appointment |

| 11 | Hereditary haemochromatosis | No appointment required (lack of consensus about reject/manage with letter) |

| 12 | Mitochondrial disease | Accept for routine, consultant, face-to-face appointment |

| 13 | Neural tube defect | Accept for routine, GC, face-to-face appointment |

Participants were asked to triage each referral by type of appointment; urgency; designated clinician, etc., using a standardised triage stamp (Fig. 2). Completed triage forms were posted back to the lead author in the coordinating centre. Data were tabulated and analysed using SPSS v23.

Fig. 2.

Triage stamp

Results

Participants

In total, 53 clinicians from six centres participated in the simulated triage exercise. Participants included 27 consultants (51%), 19 genetic counsellors (36%) and 7 (13%) specialist registrars (Table 2). All participants from Centre 5 were consultants‚ as the local practice dictates that only consultants perform triage. In Centres 4 and 6, certain consultants perform triage for both general and cancer cases, while others triage only one category or the other. Depending on their local practice, some clinicians declined to triage certain simulated referrals.

Table 2.

Participants

| Genetic counsellor | Specialist registrar | Consultant | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| Centre 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Centre 3 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Centre 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Centre 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Centre 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 10 |

Significant variability in the process of triage was noted across the six centres. In three centres (Centres 1, 4 and 5), triage of general referrals was undertaken by consultants only, and in the other three centres, by consultants and GCs. Triage of cancer referrals was, conversely, done by GCs only in three centres (Centres 1, 2 and 4), and by consultant only in Centres 5 and 6. All centres accept referrals by letter. Five centres accept electronic referrals, and four accept referral by fax (Table 3).

Table 3.

Triage process in each participating centre

| Centre | Population served | Referrals/ year | Referrals/ 1000/year | Referral/clinician/ year | Consultants* | GCs* | % referrals rejected outright | % referrals managed by letter/leaflet | % referrals managed by telephone | Hours of clinical activity dedicated to triage/week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre 1 | 1,800,000 | 3762 | 2.1 | 314 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Centre 2 | 3,100,000 | 8000 | 2.6 | 258 | 8 | 23 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 8 |

| Centre 3 | 4,700,000 | 3930 | 0.84 | 393 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 8 |

| Centre 4 | 1,200,000 | 2400 | 2 | 240 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 30 | 5 | 4 |

| Centre 5 | 2,500,000 | 7533 | 3.0 | 419 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 20 |

| Centre 6 | 5,000,000 | 8850 | 1.77 | 295 | 12 | 18 | 10α | 0 | 10 | |

Cons. consultant, GC genetic counsellor, E electronic, L letter, F fax

*as WTE (whole-time equivalent)

αData regarding proportion of referrals rejected compared to those managed by letter not available

Between centres, there was variability in the number of referrals per 1000 of population per annum (0.84–3/1000), and the number of referrals per consultant and per staff member, which could not be explained by average family size. Centre 3 and Centre 1 had almost equivalent numbers of referrals despite >2.5-fold difference in the size of population.

There were clear discrepancies in staffing numbers with Centre 2 being relatively well staffed and Centre 3 being very poorly staffed, with respect to both consultant and GC workforce. The ratio of referrals/staff member was the lowest in Centre 4 and the highest in Centre 1. The proportion of referrals managed without a face-to-face appointment was the highest in Centre 4 and the lowest in Centre 1 (8–38).

Acceptance of referrals to the service

Considering all clinicians, widespread variability in triage was noted (Fig. 3a). Only three (23%) of the referrals had >80% consensus about whether the referral should be accepted for a consultation. There was complete or almost complete consistency (>80% consensus) with the triage decision for five referrals (referrals 1, 3, 5, 6 and 10) amongst consultants (Fig. 3b), and consensus of 60–80% for three others (referrals 9, 12 and 13).

Fig. 3.

Triage practice. a Triaging by all clinicians; b triaging by consultants; c triaging by genetic counsellors

Significant inconsistency was noted for the other referrals, with some consultants offering a face-to-face appointment, and others managing the same referrals by providing an information letter or telephone consultation to the patient. Other clinicians elected to reject the referral and provide a referrer with information about onward management of the patient, without direct patient contact.

When triage performed by genetic counsellors was considered, only two referrals (referral 1 and 10) had >80% consensus regarding the type of consultation offered. Referrals 3, 4 and 6 showed 60–80% consensus (Fig. 3c). Consensus between and within centres is demonstrated in supplementary figures 2–12.

Prioritisation of referrals

Of those referrals offered face-to-face appointments, significant variability in priority and designated clinician was also noted (Supplementary Table 1). In a significant number of cases, clinicians did not specify priority/designated clinician (excluded).

The referral with the most agreement between clinicians was a simulated urgent referral of a pregnant woman with a family history of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Forty-eight clinicians triaged this referral, and all accepted the referral to service. In total, 47/48 specified the priority of the referral as priority (one did not specify). There was inconsistency in determining a designated clinician, with 26 (57%) triaging the case for GC appointment, and 20 (43%) for consultants (two did not specify).

Consistency within centres

Where appointments were offered, 100% consistency was noted for prioritisation of five referrals, including referral 10 as priority; as well as referrals 8, 9, 111 and 13 which were deemed routine by all participants. Certain centres were more consistent than others with respect to prioritisation of those referrals for which face-to-face appointments were offered (Supplementary Table 1). Clinicians in Centre 2 agreed on priority of an additional two referrals of those eight offered face-to-face appointments in that centre (25%), Centre 3 2/5 (40%), Centre 5, Centre 6 and Centre 1 another 4/7 (57%) and Centre 4 5/8 (63%).

With respect to designated clinicians, inconsistency across each referral was noted. In Centre 3, of eight referrals offered appointments, there was agreement between participants there for a designated clinician in five (63%) appointments. In Centre 2 and Centre 4, all referrals would be offered appointments by at least one clinician2, but there was agreement in these centres with respect to a designated clinician in only two (15%) cases.

Discussion

Clinical triage is an important step in all specialties, aiming to ensure prioritisation of referrals and maintain equity of access. Our study has shown widespread inconsistencies in managing common referral scenarios both within and between six Clinical Genetic units in the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Inconsistencies were noted with respect to acceptance of referrals to the service, prioritisation of referrals and type of clinic to which the referral was assigned.

Discrepancy between centres with respect to the type of consultation offered to patients may be attributed to hospital management systems; in the Republic of Ireland; referrals that were not offered a face-to-face consultation were deemed rejected, despite providing the patient with information directly, whereas similar practices in centres in UK system were acknowledged, and remunerated, as clinical activity. However, this does not explain the differences between clinicians within centres. Differences in priority assigned to cases may be influenced by waiting lists and staffing, which vary between centres. It is possible that decision-making with respect to assignment of cases to a consultant or genetic counsellor may be influenced by the level of expertise of staff within the unit.

Traditionally, research on triage has concentrated on pre-hospital, trauma, acute or emergency care settings [27–31]. Assessment of triage in tertiary referrals specialties has also concentrated on optimising management in the acute scenario [32]. Appropriate triage in tertiary referral setting is important to ensure equity of care, timely access based on need and an ability to manage waiting lists in accordance with staffing levels [33–36]. Prioritisation of the most urgent referrals is critical when waiting lists deteriorate and timely access to care is at risk [37–39]. Each speciality will have specific drivers that influence the ebb and flow of referrals. Triage decision-making in Clinical Genetics is driven by many factors related to the centre in question (e.g., staffing levels, skill mix, waiting list times and population demographics), the patient to which referral pertains (e.g., pregnant patient, patient approaching end of life, patient age and patient at risk of inheriting a familial variant) or nature of the referral itself (request for genetic information to determine treatment, advice to interpret genetic test results and adequacy of information on referral letter).

Factors known to influence referral rates include education of referrers, the genetics workforce and logistic factors [40, 41]. We noted regional differences in referral rates/1000 population, which have not previously been described. A number of factors may account for these apparent differences. Genetic disorders may be more prevalent in countries where there are endogamous populations (e.g., Irish Travellers), with associated founder mutations and disorders [42]; and among populations where first-cousin marriage is permitted, with associated increased incidence of recessive disorders. Birth rates in the Republic of Ireland (13.5 per 1000) and Northern Ireland (13.1/1000) are higher than the reported 11.8/1000 in England, Scotland and Wales, and these‚ together with the lack of availability of termination of pregnancy on the island of Ireland result in more urgent live-born referrals which may impact regional differences in referral rates.

The March of Dimes describes that a fundamental role of a Clinical Genetic service is prevention [43]. One component of this is to offer cascade genetic testing to at-risk relatives of patients with confirmed genetic disorders. Many referrals may therefore be generated by a single family once a pathogenic genetic variant is identified. Cascade screening is particularly burdensome in countries with large family sizes. In Ireland, the average size of an extended three-generation family [including siblings of grandparents and their offspring] is >3 times (64 vs. 19) that of average families in England/Wales and Scotland (Fig. 4) [44, 45]. Unsurprisingly, cascade screening for common dominant genetic disorders accounts for 12% of general referrals in Ireland. Regional differences in referral rates may be further explained by differences in management of such referrals. In some centres, at-risk relatives may self-refer by telephone or email. Furthermore, other relatives may opt to attend the appointment offered to one individual in the family to “skip the queue”. Generally, these patients are facilitated, counselled and treated, but may not be recorded as a “referral”. Other centres require formal referrals from GPs or secondary care to facilitate review of relatives for cascade testing.

Fig. 4.

Average extended three-generation family size in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and England, Scotland and Wales

Population demographics and local policies cannot completely account for the lack of consistency within units. In certain units, genetic counsellors perform “pre-clinic” for consultants; and this may explain the variability in assignment of a designated consultant. Some participants may have selected a “genetic counsellor” based on the first appointment to which referral would be assigned, while others may have selected a “consultant” as a referral would ultimately end up in a consultant clinic. In centres where genetic counsellor staffing levels are sub-optimal, pre-clinics are not possible.

In most specialties, priority is defined by urgency of the referral, which may not be appropriate in specialties like Clinical Genetics, where most referrals are non-urgent [46]. Defining priority by urgency may therefore disadvantage the majority of patients referred to Clinical Genetics [39], putting routine waiting lists under strain. There are no current guidelines one can use to determine priority of referral, although a shared set of prioritisation criteria have been proposed—including the clinical and non-clinical benefits to patient and family; risk, progression and severity of disease, and cost and infrastructure for testing [47, 48].

In our study, it is likely that other factors, such as local waiting lists, availability of regional specialist clinics or human subjectivity may explain the inconsistencies we have observed within each centre. Certain specific situations (e.g., if genetic diagnosis required prior to undergoing surgery, starting new treatment, accessing services etc.) may mean that cases that might otherwise be rejected or managed by letter will be offered face-to-face appointments. All centres involved in this study are training centres for clinical geneticists, and common conditions that might otherwise be deflected to another specialty might be accepted to fulfil curricular requirements.

Limitations of this study

Each individual centre faces different pressures with respect to staffing and waiting lists, which will, in turn, impact triage practice. It is possible that the process might differ in each centre when dealing with real referrals, all participants knew this was a research study and that referrals were high-fidelity simulations; participants may therefore have been more casual in their answers. We did not collect data specifically with respect to waiting times for routine or priority appointments. We note the NHS guideline of a maximum of 18 weeks, but appreciate that many centres in the United Kingdom struggle to avoid breaching this timeline. As a direct consequence of poor staffing levels, in the Republic of Ireland, the waiting times for priority appointments are in the order of 12–14 months, and for routine, 18–24 months. Attempts to recruit and retain trainees and genetic counsellors; and upskill non-genetic specialist is a continuing challenge.

Conclusion

The consensus in triage established in this paper should form the basis for guidelines to help an equitable consistent approach to these 13 common referrals. Individual centres will need to establish more standardised local policies in the context of their own staffing levels and availability of regional specialist clinics, but national/international guidelines are required to ensure equity in the triage process. We are mindful that we have examined the process with 13 common referrals; ensuring consistency is likely to be even more challenging when addressing the complex referrals received by all clinical genetics services. We would suggest that this issue should be considered in a European context, possibly by convening a workshop at the European Society of Human Genetics annual meeting.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Professor Andrew Green, Dr. Esther Kinning and Dr. Tabib Dabir for their assistance in data collection. We thank all our clinical colleagues for participating.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

In one centre, referrals pertaining to hereditary haemochromatosis are deferred to gastroenterology so are not offered appointments in the Clinical Genetics unit

Referral 7 was offered an appointment by only one clinician in Centre 2, and by two clinicians in Centre 4

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-018-0322-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.CGS. Roles of the Clinical Geneticist. 2011.

- 2.Turnpenny PD, Flinter FA. Clinical genetics. In: Patternson L, editor. Consultant physicians working with patients: the duties, responsibilities and practice of physicians in medicine. Royal College of Physicians. 11 St Andrews Place, Regent's Park, London NW1 4LE, 2013.

- 3.OMIM. OMIM statistics. 2018. www.omim.org. Accessed 9 May 2018.

- 4.Cheon JY, Mozersky J, Cook-Deegan R. Variants of uncertain significance in BRCA: a harbinger of ethical and policy issues to come? Genome Med. 2014;6:121. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman-Andrews L. The known unknown: the challenges of genetic variants of uncertain significance in clinical practice. J Law Biosci. 2017;4:648–57. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsx038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med: Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2015;17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heald B, Rybicki L, Clements D, et al. Assessment of clinical workload for general and specialty genetic counsellors at an academic medical center: a tool for evaluating genetic counselling practices. Npj Genom Med. 2016;1:16010. doi: 10.1038/npjgenmed.2016.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarrei M, MacDonald JR, Merico D, Scherer SW. A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:172. doi: 10.1038/nrg3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Shehhii M KR, Lynch SA. Impact of Advanced Genomics on Health Services; Department of Clinical Genetics as an example. (presented at OLCHC Audit Day 2016). Our Lady's Children's Hospital Crumlin, 2016.

- 10.Wu P, Nielsen TE, Clausen MH. Small-molecule kinase inhibitors: an analysis of FDA-approved drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McVeigh TP, George AJ. Personalisation of therapy – clinical impact and relevance of genetic mutations in tumours. Cancer Res Front. 2017;3:29–50. doi: 10.17980/2017.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans DGR, Barwell J, Eccles DM, et al. The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res : BCR. 2014;16:442. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manchanda R, Patel S, Antoniou AC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population based BRCA testing with varying Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:578.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel S, Legood R, Evans DG, et al. Cost effectiveness of population based BRCA1 founder mutation testing in Sephardi Jewish women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:431.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manchanda R, Patel S, Gordeev VS, Antoniou AC, Smith S, Lee A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Population-Based BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, RAD51D, BRIP1, PALB2 mutation testing in unselected general population women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:714–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Information K. The Market for Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Health Testing. Pub ID: KLI15569647. 2018.

- 17.Phillips AM. ‘Only a click away — DTC genetics for ancestry, health, love…and more: A view of the business and regulatory landscape’. Applied & Translational Genomics. 2016;8:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atg.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes C, Kerzin-Storrar L, Skirton H, Tocher J. The department of health-supported genetic counsellor training post scheme in England: a unique initiative? J Community Genet. 2012;3:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s12687-012-0100-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamin C, Houghton C, Foo C, et al. A prospective cohort study assessing clinical referral management & workforce allocation within a UK regional medical genetics service. Eur J Human Genet. 2015;23:996–1003. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch SA, Borg I. Wide disparity of clinical genetics services and EU rare disease research funding across Europe. J Community Genet. 2016;7:119–26. doi: 10.1007/s12687-015-0256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taverner NV. GC Workforce Survey (on behalf of AGNC committee). Association of Genetic Nurses and Counsellors, 2017.

- 22.Murray A, Davies S. Who’s who in Clinical Genetics. An exercise in workforce identification and planning. Clin Genet Society. 2004.

- 23.Clayton-Smith J, Newbury-Ecob R, Cook J, Greenhalgh L. The evolving role of the clinical geneticist: a summary of the workshop hosted by the Clinical Genetics Society. Clin Genet Society. British Society for Genetic Medicine, Charles Darwin House, Roger Street, London, 2014.

- 24.Kelly R, Lynch SA. Triage of Referrals in NCMG. Presentation, Joint Belfast/Dublin meeting. Daisy Hill Hospital; Newry 2013.

- 25.Kneebone R. Simulation, safety and surgery. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:i47–52. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lateef F. Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. J Emergencies, Trauma Shock. 2010;3:348–52. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerdtz M, Chu M, Collins M, et al. Factors influencing consistency of triage using the Australasian Triage Scale: Implications for guideline development. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:277–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handy P, Pattman R. Triage up front. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:59–62. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenyon S, Hewison A, Dann SA, et al. The design and implementation of an obstetric triage system for unscheduled pregnancy related attendances: a mixed methods evaluation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:309. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1503-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JH, James RE, Davey R, Waddington G. What is orthopaedic triage? A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:128–36. doi: 10.1111/jep.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Cathain A, Webber E, Nicholl J, Munro J, Knowles E. NHS direct: consistency of triage outcomes. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:289–92. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamed K, Al Houri B, Ibrahim K, M Khair A. Improving access for urgent patients in paediatric neurology. BMJ QIR. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.NHSIMAS, Elective Care Guide: Referral to Treatment Pathways: A Guide for Managing Efficient Elective Care. National Health Service Interim Management and Support (NHS IMAS), 2014.

- 34.NHS. NHS Constitution for England. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/resources/rtt/. Accessed 8 May 2018.

- 35.Hazlewood GS, Barr SG, Lopatina E, et al. Improving appropriate access to care with central referral and triage in rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1547–53. doi: 10.1002/acr.22845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deluca J, Goldschmidt A, Eisendle K. Analysis of effectiveness and safety of a three-part triage system for the access to dermatology specialist health care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1190–4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal L, Guy S, Leach M, Groves A, Turnbull C, Furber G. A needs-based workforce model to deliver tertiary-level community mental health care for distressed infants, children, and adolescents in South Australia: a mixed-methods study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e296–303. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stainkey LA, Seidl IA, Johnson AJ, Tulloch GE, Pain T. The challenge of long waiting lists: how we implemented a GP referral system for non-urgent specialist' appointments at an Australian public hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:303–303. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naiker U, FitzGerald G, Dulhunty JM, Rosemann M. Time to wait: a systematic review of strategies that affect out-patient waiting times. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42:286–93. doi: 10.1071/AH16275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delikurt T, Williamson GR, Anastasiadou V, Skirton H. A systematic review of factors that act as barriers to patient referral to genetic services. Eur J Human Genet. 2015;23:739–45. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucassen A, Watson E, Harcourt J, Rose P, O'Grady J. Guidelines for referral to a regional genetics service: GPs respond by referring more appropriate cases. Fam Pract. 2001;18:135–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch SA, Crushell E, Lambert DM, Byrne N, Gorman K, King MD, et al. Catalogue of inherited disorders found among the Irish Traveller population. J Med Genet. 2018;55:233–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Howson CP, Christianson A, Modell B. March of Dimes Global Report: Controlling Birth Defects: Reducing the Hidden Toll of Dying and Disabled Children in Low-Income Countries. In Disease Control Priorities Project. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, White Plains, New York, 2008.

- 44.Fahey T. Trends in Irish fertility rates in comparative perspective. Econ & Social Rev. 2001;32:153–80. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiting S. Socio-demographic comparison between those UK families with up to two children and those with three or more. 2012. www.populationmatters.org.

- 46.Harding KE, Taylor NF, Leggat SG, Stafford M. Effect of triage on waiting time for community rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:441–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Severin F, Borry P, Cornel MC, et al. Points to consider for prioritizing clinical genetic testing services: a European consensus process oriented at accountability for reasonableness. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:729–35. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Severin F, Schmidtke J, Muhlbacher A, Rogowski WH. Eliciting preferences for priority setting in genetic testing: a pilot study comparing best-worst scaling and discrete-choice experiments. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:1202–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.