Abstract

Epidemiological and genetic studies have pointed to the role of cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We explored the interaction of a genetic risk score (GRS) of AD risk alleles with mid-life plasma lipid levels (LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides) on risk for AD in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). Mid-life (between the ages of 40–60 years old) lipid levels were obtained from individuals in the FHS Original and Offspring cohorts (157 cases and 2,882 controls) with genetic data and AD status available. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to test the interaction between mid-life lipid levels and an AD GRS, as well as the individual contributing SNPs, on risk of incident AD adjusting for age, sex, and cohort. We found a significant interaction between a GRS of AD loci and log triglyceride levels on risk of clinical AD (p=0.006), but no interaction of the GRS with HDL-C (p=0.458) or LDL-C (p=0.366). We then tested the interaction between the individual SNPs contributing to the GRS and log triglycerides. We found two SNPs that had interactions with triglycerides on AD risk that reached a p-value < 0.05 (rs11218343 and APOE e4). The association between some AD SNPs and risk of AD may be modified by triglyceride levels. Furthermore, sequential testing of a GRS with a set of traits on disease followed by testing individual SNPs for interaction provides a framework for narrowing the associations that need to be tested for interaction analyses. Replication is needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cohort studies, risk factors in epidemiology, association studies in genetics

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a debilitating neurological disease affecting more than 5 million individuals living in the United States[1]. Both genetic and environmental risks for AD have been identified. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) e4 allele is an established genetic risk factor for AD. Along with roles in neuronal growth, repair response to tissue injury, and nerve regeneration, APOE is critical in the transport of cholesterol and other lipids, and activation of lipolytic enzymes. Additionally, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 20 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with late-onset AD and have provided evidence that AD is multi-factorial[2]. One of the pathways implicated by AD GWAS is cholesterol and lipid metabolism. Variants in three genes: APOE, Clusterin (CLU) and ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 7 (ABCA7) have been identified by both AD and lipid GWAS studies. These genes also have been shown to have influences on amyloid-β (Aβ), a biomarker of AD [3, 4].

Epidemiological studies have also pointed to the role of cholesterol and triglycerides in cognitive decline[5] and AD[6, 7] and specifically mid-life cholesterol, where increased total cholesterol is associated with an increased risk of AD[8], although this was not confirmed in other cohorts[9]. This heterogeneity in the effects of lipid levels on AD could be explained by genetics. Whether lipid levels interact with AD genetic variants to modulate risk for AD is not known. We aimed to identify genetic interactions between AD risk SNPs and mid-life plasma lipid levels on AD risk. We first tested the interaction between a genetic risk score (GRS) of previously identified AD risk SNPs. We then tested the interaction with lipid levels for individual SNPs contributing to the GRS. Unraveling these interactions can aid in identifying sub-groups of individuals based on genetics, which can be assayed before clinical symptoms manifest, that are more susceptible to altered plasma lipid levels on risk of AD.

METHODS

Framingham Heart Study

The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) is a community-based, longitudinal cohort study that was initiated in 1948. The original cohort comprised 5,209 residents of Framingham, Massachusetts, and these participants have undergone up to 32 examinations, performed every 2 years, that have involved detailed history taken by a physician, a physical examination, and laboratory testing [10]. In 1971, a total of 5,214 offspring of the participants in the original cohort and the spouses of these offspring were enrolled in an offspring cohort. The participants in the offspring cohort have completed up to 9 examinations, which have taken place every 4 years [11].

All participants have provided written informed consent. Study protocols and consent forms were approved by the institutional review board at the Boston University Medical Center.

Definition of AD

The diagnosis of AD is based on criteria for possible, probable, or definite AD from the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS–ADRDA) [12, 13].

The surveillance methods for the FHS have been published previously [14, 15], and details about AD tracking are available elsewhere [16]. In brief, cognitive status has been monitored in the original cohort since 1975, when comprehensive neuropsychological testing was performed. Since 1981, participants in the original cohort have been assessed at each examination with the use of the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE)[17]; participants are flagged for further cognitive screening if they have scores below the pre-specified cutoffs, which are adjusted for educational level and prior performance. Participants in the offspring cohort have undergone similar monitoring[18]; they answered a subjective memory question in 1979, have undergone serial MMSEs since 1991, and have taken a 45-minute neuropsychological test every 5 or 6 years since 1999.

A dementia review panel, which includes a neurologist and a neuropsychologist, has reviewed every case of possible cognitive decline and dementia ever documented in the FHS. For cases that were detected before 2001, a repeat review was completed after 2001 so that up-to-date diagnostic criteria could be applied. The panel determines whether a person had dementia, as well as the dementia subtype and the date of onset, using data from previously performed serial neurologic and neuropsychological assessments, telephone interviews with caregivers, medical records, neuroimaging studies, and, when applicable and available, autopsies[14]. After a participant dies, the panel reviews medical and nursing records up to the date of death to assess whether the participant might have had cognitive decline since his or her last examination[19].

We set the baseline age of entry to 65 years old; follow-up began at age 65 or at entry date for those that entered AD surveillance after age 65. We set no minimum follow-up time and a maximum follow-up of 20 years.

Plasma Lipids Levels

Fasting high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides in mg/dl units were obtained from the clinical exam with an age closest to age 50 to represent mid-life lipid level. Individuals without lipid levels measured in the range of 40–60 years old were excluded. Triglyceride levels were not normally distributed and a log transformation was used before analysis.

We defined lipid extremes by two approaches: (1) as the clinically deviant sex-specific 5th percentiles from the publicly available National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013–2014 lipid ascertainment, and (2) as the established cut-off values from the National Cholesterol Education Program ATP III guidelines. NHANES is designed to be representative of United States demographics and aims to ascertain health, nutrition, and clinical outcomes data (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). Males with LDL-C ≥ 169 mg/dl and female with LDL-C ≥ 168 mg/dl were considered to have high LDL-C. Males with triglycerides ≥ 287 mg/dl and females with triglycerides ≥ 226 mg/dl were considered to have high triglycerides. Males with HDL-C ≤ 31 and females with ≤ 35 were considered to have low HDL-C. Using the NCEP-ATP III guidelines, we defined low HDL-C as < 40 mg/dl, high LDL-C as ≥ 190 mg/dl, and high triglycerides as ≥ 200 mg/dl.

We additionally obtained each participant’s lipid lowering medication status, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of type 2 diabetes, prevalent coronary heart disease, and prevalent stroke at the same exam as the lipid levels.

Genotypes

FHS participants had DNA extracted and provided consent for genotyping in the 1990s. All available eligible participants were genotyped at Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) through an NHLBI funded SNP-Health Association Resource (SHARe) project using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array Set and 50K Human Gene Focused Panel. 1000Genomes genotypes were imputed using Mach/Minimac as previously done[2]. Twenty SNPs previously reported to be associated with AD [2] were extracted (imputation quality > 0.25; Supplemental Table 1). One reported SNP was not available (rs9271192). Despite low imputation quality for 2 SNPs, we included them as to capture some of the information from that SNP in the GRS. Additionally, APOE e4 genotypes were obtained. A weight genetic risk score (GRS) was created based by summing the 20 SNPs previously reported to be associated with AD plus the APOE e4 genotype multiplied by their reported effect size [2] on AD as weights (Supplemental Table 1). That is, for each individual i, . A weight of 1.31 was used for APOE e4 [20]. The GRS was highly associated with AD in our sample (hazards ratio =2.633, p = 8 × 10−22) after adjusting for age, sex, and generation.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in the FHS using the original cohort and offspring participants with fasting lipids levels and genotype data. Individuals with lipid levels available between the ages of 40 and 60 years old where included in analysis. For each lipid level, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression to test the interaction of the GRS with each lipid level on AD. All models were adjusted for age, sex, and cohort.

We applied a Bonferroni correction adjusting for testing three lipid levels for interaction with the GRS (0.05/3=0.017). For interactions that reached our Bonferroni corrected alpha level, we tested the interaction, separately, between each SNP contributing to the GRS with the relevant lipid level using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with an additive coding of the SNP adjusting for age, sex, and cohort. We did not apply a multiple testing correction when testing the individual SNPs contributing to the GRS.

All analysis were conducted in SAS and R-3.3.1.

RESULTS

Of the 10,333 original and offspring cohort individuals, a total of 3,040 individuals were available in the FHS with AD status, at least one midlife plasma lipid level, and genotypes (Table 1). We found that AD cases were more likely to be female (63% vs. 54%, p=0.03), slightly older (52.0 vs. 51.3 years, p=0.005), and have a longer follow-up time (13.9 vs. 11.3 years, p<0.001) compared with the controls. The longer follow-up in the cases is likely due to a loss-to-follow-up in the controls. Cases also had higher average LDL-C (p=0.001) and triglycerides (p=0.01) compared with controls (Table 1). We did not find a differences in lipid lowering medication, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, prevalent type 2 diabetes, stroke, or coronary heart disease between cases and controls (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of FHS individuals tested for interaction between genetics and plasma lipids on risk of AD.

| Variable | AD Cases | Controls | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 157 | 2883 | |

| Female | 99 (63%) | 1566 (54%) | 0.032 |

| Age | 52.0±3.0 | 51.3±2.8 | 0.005 |

| Offspring Cohort | 105 (67%) | 2367 (82%) | <.0001 |

| Follow-up time | 13.9±4.4 | 11.3±6.6 | <.0001 |

| HDL-C | 54.4±18.0 | 52.6±16.3 | 0.180 |

| LDL-C | 148.3±39.9 | 138.4±36.4 | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides | 203.4±198.2 | 172.5±174.6 | 0.013** |

| % on lipid lowering treatment | 2 (1%) | 73 (3%) | 0.320 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 124.5±14.4 | 125.6±16.9 | 0.434 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 26.0±4.0 | 26.7±4.5 | 0.093 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 6 (4%) | 96 (4%) | 0.745 |

| Stroke | 22 (14%) | 303 (11%) | 0.167 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 34 (22%) | 673 (23%) | 0.626 |

Continuous variables displayed as mean±standard deviation and categorical variables are displayed N (percentage).

p-value comparing cases and controls using a two-sample t-test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables

p-value for log(triglycerides)

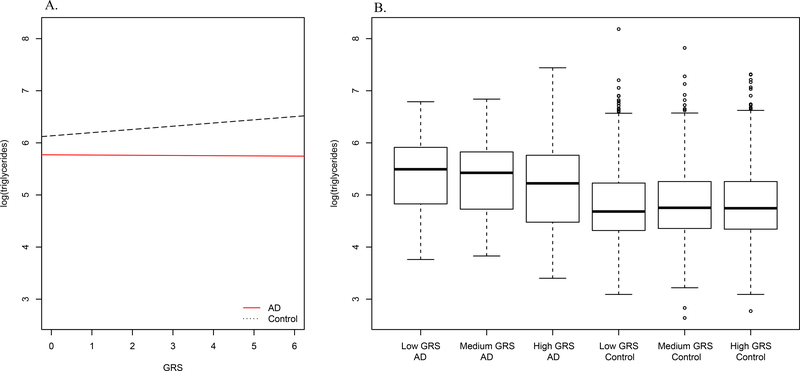

We first tested the interaction between the GRS and each plasma lipid level on risk for AD. We found a significant interaction between the GRS and log triglyceride levels on AD status (p=0.006), but no interaction of the GRS with LDL-C (p=0.366) or HDL-C (p=0.458) (Table 2). We observed that in controls, the GRS tracks with increased triglyceride levels (p=0.0003) (Figure 1A). Due to the low number of AD cases, it is difficult to interpret the relationship between the GRS and log triglycerides in the cases. Splitting the GRS into tertiles suggests that an increase in the GRS is associated with a decrease in triglyceride levels in AD cases, though not significant (beta=−0.004, p=0.94), but an increase in triglyceride levels in controls (beta=0.06, p=0.0003) (Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Interactions between AD GRS and lipid levels on AD status in up to 3039 FHS individuals.

| Lipid Interactor | N Cases | N Total | Beta | SE | pval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous lipid level | |||||

| HDL-C | 156 | 2995 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.458 |

| LDL-C | 156 | 2995 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.366 |

| Log (triglycerides) | 157 | 3039 | −0.353 | 0.129 | 0.006 |

| Extreme lipid level categorized by sex-specific 5th-percentiles of NHANES data | |||||

| Low HDL-C | 156 | 3031 | 0.168 | 0.314 | 0.593 |

| High LDL-C | 156 | 2995 | −0.157 | 0.243 | 0.518 |

| High triglycerides | 157 | 3039 | −0.573 | 0.254 | 0.024 |

| Extreme lipid level categorized by ATP III clinical definitions | |||||

| Low HDL-C | 157 | 3040 | 0.011 | 0.224 | 0.960 |

| High LDL-C | 156 | 2995 | −0.043 | 0.303 | 0.887 |

| High triglycerides | 157 | 3039 | −0.655 | 0.223 | 0.003 |

Figure 1. Relationship between triglycerides and AD GRS by AD status.

(A). Relationship between the genetic risk score (GRS) (x-axis) and log(triglycerides) (y-axis) separately by AD status shows that in controls, an AD SNP derived GRS tracks with increased triglyceride levels. (B). Categorizing the GRS into tertiles (low, medium, and high) suggests that an increase in the AD GRS is associated with a decrease in triglyceride levels.

We performed three sensitivity analyses. Firstly, we categorized the lipids into extremes and tested the interaction between having an extreme lipid level and the GRS on risk of AD. We found consistent results when using either extremes defined as sex-specific 5th-percentiles in a reference population or using established clinical cut-offs compared to using continuous lipid levels. That is, high triglycerides showed evidence of an interaction with the GRS while low HDL-C and high LDL-C did not show evidence of an interaction (Table 2). Secondly, we adjusted for midlife systolic blood pressure (SBP) and body mass index (BMI) in the models and found consistent results to the models not adjusting for SBP and BMI (p=0.65 for GRS*HDL-C interaction, p=0.50 for GRS*LDL-C interaction, and p=0.01 for GRS*log triglycerides interaction). Finally, we tested the interaction between each lipid level and the GRS on dementia. We found consistent results to when AD was used as the outcome (p=0.60 for GRS*HDL-C interaction, p=0.41 for GRS*LDL-C interaction, and p=0.008 for GRS*log triglycerides interaction).

Next, we tested the interaction between the individual variants contributing to the GRS and triglycerides. We found interactions between two variants with triglycerides on AD that reached a p-value < 0.05 (rs11218343 and APOE e4) (Table 3). To aid the interpretation of the effects for the interactions we performed stratified analyses. While not significant due to the low number of cases in the stratified analyses (85 e4 negative cases and 72 e4 positive cases), we found that the direction of the relationship between log triglycerides and AD differs based on APOE e4 status. In carriers of APOE e4 (n=667), there is a negative relationship between log triglycerides and AD (beta= −0.084, p=0.92), while in non-carriers of APOE e4 (n=2,372), there is a positive association between log triglycerides and AD (beta=0.33, p=0.13). And, while not statistically significant, in 1,978 APOE e3/e3 individuals, there is a positive relationship between log triglycerides and AD (beta=0.36, p=0.13). Furthermore, the effect of e4 status on AD is smaller in those with high triglycerides (hazard ratio=2.4, p=0.0117 in 38 cases of 555 total) compared to those without high triglycerides (hazard ratio=4.7, p<0.0001 in 119 cases of 2484 total).

Table 3.

Interactions between SNPs constituting the GRS and log triglycerides on incident AD in the FHS with p < 0.05.

| Interaction | SNP minor allele frequency | Beta | StdErr | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log(triglycerides)*APOE dosage | 0.12 | −0.323 | 0.156 | 0.037 |

| Log(triglycerides)*rs11218343 | 0.04 | −0.773 | 0.295 | 0.009 |

Finally, we found that the effect of triglycerides on AD varies by rs11218343 (at the SORL1 locus). While not significant in stratified analyses by AD status, the association between rs11218343 and triglyceride levels is stronger in individuals with AD compared with the controls. In individuals with AD, rs11218343 is negatively correlated with triglyceride levels (beta=−0.25, p=0.08), but this association is in the opposite direction and not as strong in controls (beta=0.018, p=0.60). In a large publicly available meta-analysis of plasma lipids[21], there is no observed association in the SORL1 locus with triglycerides or HDL-C, and a marginal genome-wide association with LDL-C (p~1×10−5; Supplemental Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have explored the relationship between lipids and AD risk with inconsistent results[8, 9, 22–25]. One possible explanation for the inconsistency in results is gene by environment interaction where subsets of individuals have different risk of AD for an “environmental” exposure, in this case lipid level, based on their genetic markers. Additionally, a number of genes have been implicated for both lipids and AD risk[2, 26, 27].

In this study, we demonstrated an interaction between a GRS of AD risk SNPs and triglyceride levels on risk of AD in the FHS. We did not observe an interaction between the GRS and LDL-C or HDL-C. Given the observed interaction between the GRS and triglycerides, we tested the interaction between each of the individual SNPs contributing to the GRS and triglycerides to refine which SNPs were contributing to the interactions with the GRS. We found 2 genotypes, APOE e4 and rs11218343, where the association between AD SNPs and risk of AD may be modified by triglyceride levels. rs11218343 is an intronic SNP upstream from the Sortilin-related receptor (SORL1). SORL1 is a neuronal apolipoprotein E receptor with links to LDL-C but not with triglycerides or HDL-C[21].

While the genetic markers are not modifiable, triglyceride levels can be modified by diet, lifestyle, and medications. Since we know our genetic markers before onset of clinical symptoms, this information can be used to tailor preventive strategies targeting triglyceride levels. We found that for an AD-specific GRS as well as two SNPs previously associated with AD status, the association between AD and genetic markers is modified by a modifiable factor (triglycerides), indicating (1) that the genetic effect can be tempered, and (2) that risk of AD from triglyceride levels vary based on genetic markers. Furthermore, in addition to treating high triglyceride levels for reducing risk of coronary heart disease, we found that in APOE e4 negative individuals, there is a relationship between increased triglyceride levels and increased AD risk, and therefore, treating triglycerides could also decrease risk of AD in e4 negative individuals. Our results suggest that if an individual does not carry any e4 alleles, then triglycerides have an effect on AD risk, but if an individual does carry any e4 allele then that is the driver of the AD risk.

The advantages of our study include comprehensive diagnoses with adjudicated outcomes and over 10 years of longitudinal follow-up. We used lipid levels measured at mid-life to diminish the role AD has on changes in lipid levels. The Three-City (3C) study found that risk of AD was associated with both LDL-C and total cholesterol at baseline, but that the association between higher triglyceride concentrations and dementia disappeared after adjusting for vascular risk factors[9]. We did not observe diminishing associations after adjustment for midlife systolic blood pressure, suggesting that vascular risk factors are not contributing to our observed associations.

Limitations of our study include, first, FHS is composed of individuals of European descent and therefore these results may not be generalizable to non-European populations. Samples of European ancestry were used to derive the weights for the GRS[2], therefore, the GRS is most appropriately applied to a European ancestry sample. Second, the interaction between a GRS of AD risk SNPs and triglyceride levels on risk of AD in the FHS survives a Bonferroni correction for testing three interactions but the two individual SNPs would not survive a multiple testing correction and should be considered exploratory evidence for interactions between these SNPs and triglyceride levels. Third, since APOE influences lipid levels, they are not independent, which can result in increased type I error for the interaction. Fourth, the study only considers late-onset AD (after age 65) and the shape of the GxE interaction may vary according to age of onset, which we do not have power to test. The SNPs contributing to the GRS were derived from a study for late-onset AD[2] and therefore are most appropriate for this definition of AD. Finally, our study design does not allow for inference on the nature of the interaction.

In summary, in a population-based sample, we found an interaction between a GRS comprised of AD SNPs and midlife triglyceride levels on risk of AD, but no interaction of the GRS with midlife LDL-C or HDL-C. These associations were independent of midlife systolic blood pressure. Further studies are needed to replicate the interactions between the AD GRS and triglyceride levels and rule out potential false positive findings. If confirmed, this suggests that an AD-specific GRS can help tease apart the relationships between AD and plasma lipid levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Framingham Heart Study participants, the study team and the investigators and staff of the neurology team. The Framingham Heart Study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract no. N01-HC-25195 and no. HHSN268201500001I) and by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG054076, R01 AG049607, R01 AG033193, U01 AG049505, U01 AG052409) and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NS0 17950 and UH2 NS100605). Funding for SHARe Affymetrix genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. G.M. Peloso is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01HL125751.

Footnotes

Disclosures Statement

G. Peloso, A. Beiser, A. Destefano, S. Seshadri report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association (2016) 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 12, 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, Russo G, Thorton-Wells TA, Jones N, Smith AV, Chouraki V, Thomas C, Ikram MA, Zelenika D, Vardarajan BN, Kamatani Y, Lin CF, Gerrish A, Schmidt H, Kunkle B, Dunstan ML, Ruiz A, Bihoreau MT, Choi SH, Reitz C, Pasquier F, Cruchaga C, Craig D, Amin N, Berr C, Lopez OL, De Jager PL, Deramecourt V, Johnston JA, Evans D, Lovestone S, Letenneur L, Moron FJ, Rubinsztein DC, Eiriksdottir G, Sleegers K, Goate AM, Fievet N, Huentelman MW, Gill M, Brown K, Kamboh MI, Keller L, Barberger-Gateau P, McGuiness B, Larson EB, Green R, Myers AJ, Dufouil C, Todd S, Wallon D, Love S, Rogaeva E, Gallacher J, St George-Hyslop P, Clarimon J, Lleo A, Bayer A, Tsuang DW, Yu L, Tsolaki M, Bossu P, Spalletta G, Proitsi P, Collinge J, Sorbi S, Sanchez-Garcia F, Fox NC, Hardy J, Deniz Naranjo MC, Bosco P, Clarke R, Brayne C, Galimberti D, Mancuso M, Matthews F, European Alzheimer’s Disease I, Genetic, Environmental Risk in Alzheimer’s D, Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic C, Cohorts for H, Aging Research in Genomic E, Moebus S, Mecocci P, Del Zompo M, Maier W, Hampel H, Pilotto A, Bullido M, Panza F, Caffarra P, Nacmias B, Gilbert JR, Mayhaus M, Lannefelt L, Hakonarson H, Pichler S, Carrasquillo MM, Ingelsson M, Beekly D, Alvarez V, Zou F, Valladares O, Younkin SG, Coto E, Hamilton-Nelson KL, Gu W, Razquin C, Pastor P, Mateo I, Owen MJ, Faber KM, Jonsson PV, Combarros O, O’Donovan MC, Cantwell LB, Soininen H, Blacker D, Mead S, Mosley TH Jr., Bennett DA, Harris TB, Fratiglioni L, Holmes C, de Bruijn RF, Passmore P, Montine TJ, Bettens K, Rotter JI, Brice A, Morgan K, Foroud TM, Kukull WA, Hannequin D, Powell JF, Nalls MA, Ritchie K, Lunetta KL, Kauwe JS, Boerwinkle E, Riemenschneider M, Boada M, Hiltuenen M, Martin ER, Schmidt R, Rujescu D, Wang LS, Dartigues JF, Mayeux R, Tzourio C, Hofman A, Nothen MM, Graff C, Psaty BM, Jones L, Haines JL, Holmans PA, Lathrop M, Pericak-Vance MA, Launer LJ, Farrer LA, van Duijn CM, Van Broeckhoven C, Moskvina V, Seshadri S, Williams J, Schellenberg GD, Amouyel P (2013) Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 45, 1452–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tosto G, Reitz C (2013) Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13, 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Van Cauwenberghe C, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K (2016) The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives. Genet Med 18, 421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Power MC, Rawlings A, Sharrett AR, Bandeen-Roche K, Coresh J, Ballantyne CM, Pokharel Y, Michos ED, Penman A, Alonso A, Knopman D, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF (2018) Association of midlife lipids with 20-year cognitive change: A cohort study. Alzheimers Dement 14, 167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shepardson NE, Shankar GM, Selkoe DJ (2011) Cholesterol level and statin use in Alzheimer disease: I. Review of epidemiological and preclinical studies. Arch Neurol 68, 1239–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Di Paolo G, Kim TW (2011) Linking lipids to Alzheimer’s disease: cholesterol and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anstey KJ, Ashby-Mitchell K, Peters R (2017) Updating the Evidence on the Association between Serum Cholesterol and Risk of Late-Life Dementia: Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 56, 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schilling S, Tzourio C, Soumare A, Kaffashian S, Dartigues JF, Ancelin ML, Samieri C, Dufouil C, Debette S (2017) Differential associations of plasma lipids with incident dementia and dementia subtypes in the 3C Study: A longitudinal, population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 14, e1002265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP (1963) An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 107, 539–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP (1979) An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol 110, 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bachman DL, Wolf PA, Linn R, Knoefel JE, Cobb J, Belanger A, D’Agostino RB, White LR (1992) Prevalence of dementia and probable senile dementia of the Alzheimer type in the Framingham Study. Neurology 42, 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Wolf PA, Evans DA, Wilson RS, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Rocca WA, Kawas CH, Corrada MM, Plassman BL, Langa KM, Chui HC (2011) Operationalizing diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related cognitive impairment-Part 2. Alzheimers Dement 7, 35–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Au R, McNulty K, White R, D’Agostino RB (1997) Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology 49, 1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chene G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S (2016) Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 374, 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Au R, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Elias M, Elias P, Sullivan L, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB (2004) New norms for a new generation: cognitive performance in the framingham offspring cohort. Exp Aging Res 30, 333–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Au R, Seshadri S, Knox K, Beiser A, Himali JJ, Cabral HJ, Auerbach S, Green RC, Wolf PA, McKee AC (2012) The Framingham Brain Donation Program: neuropathology along the cognitive continuum. Curr Alzheimer Res 9, 673–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kukull WA, Schellenberg GD, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Yu CE, Teri L, Thompson JD, O’Meara ES, Larson EB (1996) Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease risk and case detection: a case-control study. J Clin Epidemiol 49, 1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Global Lipids Genetics Consortium, Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, Kanoni S, Ganna A, Chen J, Buchkovich ML, Mora S, Beckmann JS, Bragg-Gresham JL, Chang HY, Demirkan A, Den Hertog HM, Do R, Donnelly LA, Ehret GB, Esko T, Feitosa MF, Ferreira T, Fischer K, Fontanillas P, Fraser RM, Freitag DF, Gurdasani D, Heikkila K, Hypponen E, Isaacs A, Jackson AU, Johansson A, Johnson T, Kaakinen M, Kettunen J, Kleber ME, Li X, Luan J, Lyytikainen LP, Magnusson PK, Mangino M, Mihailov E, Montasser ME, Muller-Nurasyid M, Nolte IM, O’Connell JR, Palmer CD, Perola M, Petersen AK, Sanna S, Saxena R, Service SK, Shah S, Shungin D, Sidore C, Song C, Strawbridge RJ, Surakka I, Tanaka T, Teslovich TM, Thorleifsson G, Van den Herik EG, Voight BF, Volcik KA, Waite LL, Wong A, Wu Y, Zhang W, Absher D, Asiki G, Barroso I, Been LF, Bolton JL, Bonnycastle LL, Brambilla P, Burnett MS, Cesana G, Dimitriou M, Doney AS, Doring A, Elliott P, Epstein SE, Eyjolfsson GI, Gigante B, Goodarzi MO, Grallert H, Gravito ML, Groves CJ, Hallmans G, Hartikainen AL, Hayward C, Hernandez D, Hicks AA, Holm H, Hung YJ, Illig T, Jones MR, Kaleebu P, Kastelein JJ, Khaw KT, Kim E, Klopp N, Komulainen P, Kumari M, Langenberg C, Lehtimaki T, Lin SY, Lindstrom J, Loos RJ, Mach F, McArdle WL, Meisinger C, Mitchell BD, Muller G, Nagaraja R, Narisu N, Nieminen TV, Nsubuga RN, Olafsson I, Ong KK, Palotie A, Papamarkou T, Pomilla C, Pouta A, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, Ridker PM, Rivadeneira F, Rudan I, Ruokonen A, Samani N, Scharnagl H, Seeley J, Silander K, Stancakova A, Stirrups K, Swift AJ, Tiret L, Uitterlinden AG, van Pelt LJ, Vedantam S, Wainwright N, Wijmenga C, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Wilsgaard T, Wilson JF, Young EH, Zhao JH, Adair LS, Arveiler D, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, Bennett F, Bochud M, Boehm BO, Boomsma DI, Borecki IB, Bornstein SR, Bovet P, Burnier M, Campbell H, Chakravarti A, Chambers JC, Chen YD, Collins FS, Cooper RS, Danesh J, Dedoussis G, de Faire U, Feranil AB, Ferrieres J, Ferrucci L, Freimer NB, Gieger C, Groop LC, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Hamsten A, Harris TB, Hingorani A, Hirschhorn JN, Hofman A, Hovingh GK, Hsiung CA, Humphries SE, Hunt SC, Hveem K, Iribarren C, Jarvelin MR, Jula A, Kahonen M, Kaprio J, Kesaniemi A, Kivimaki M, Kooner JS, Koudstaal PJ, Krauss RM, Kuh D, Kuusisto J, Kyvik KO, Laakso M, Lakka TA, Lind L, Lindgren CM, Martin NG, Marz W, McCarthy MI, McKenzie CA, Meneton P, Metspalu A, Moilanen L, Morris AD, Munroe PB, Njolstad I, Pedersen NL, Power C, Pramstaller PP, Price JF, Psaty BM, Quertermous T, Rauramaa R, Saleheen D, Salomaa V, Sanghera DK, Saramies J, Schwarz PE, Sheu WH, Shuldiner AR, Siegbahn A, Spector TD, Stefansson K, Strachan DP, Tayo BO, Tremoli E, Tuomilehto J, Uusitupa M, van Duijn CM, Vollenweider P, Wallentin L, Wareham NJ, Whitfield JB, Wolffenbuttel BH, Ordovas JM, Boerwinkle E, Palmer CN, Thorsteinsdottir U, Chasman DI, Rotter JI, Franks PW, Ripatti S, Cupples LA, Sandhu MS, Rich SS, Boehnke M, Deloukas P, Kathiresan S, Mohlke KL, Ingelsson E, Abecasis GR (2013) Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet 45, 1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Iivonen S, Mannermaa A, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A, Soininen H (2002) Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele, elevated midlife total cholesterol level, and high midlife systolic blood pressure are independent risk factors for late-life Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med 137, 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K (2005) Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology 64, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Solomon A, Kivipelto M, Wolozin B, Zhou J, Whitmer RA (2009) Midlife serum cholesterol and increased risk of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia three decades later. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 28, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Li G, Shofer JB, Kukull WA, Peskind ER, Tsuang DW, Breitner JC, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, Larson EB (2005) Serum cholesterol and risk of Alzheimer disease: a community-based cohort study. Neurology 65, 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].El Gaamouch F, Jing P, Xia J, Cai D (2016) Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Genes and Lipid Regulators. J Alzheimers Dis 53, 15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Desikan RS, Schork AJ, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Dehghan A, Ridker PM, Chasman DI, McEvoy LK, Holland D, Chen CH, Karow DS, Brewer JB, Hess CP, Williams J, Sims R, O’Donovan MC, Choi SH, Bis JC, Ikram MA, Gudnason V, DeStefano AL, van der Lee SJ, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Launer L, Seshadri S, Pericak-Vance MA, Mayeux R, Haines JL, Farrer LA, Hardy J, Ulstein ID, Aarsland D, Fladby T, White LR, Sando SB, Rongve A, Witoelar A, Djurovic S, Hyman BT, Snaedal J, Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Schellenberg GD, Andreassen OA, Dale AM, Inflammation working group I, DemGene I (2015) Polygenic Overlap Between C-Reactive Protein, Plasma Lipids, and Alzheimer Disease. Circulation 131, 2061–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.