Abstract

Background:

Patients who are sick enough to be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) commonly experience symptoms of psychological distress after discharge, yet few effective therapies have been applied to meet their needs.

Methods:

Pilot randomized clinical trial with 3-month follow up conducted at two academic medical centers. Adult (≥18 years) ICU patients treated for cardiorespiratory failure were randomized after discharge home to one of three month-long interventions: a self-directed mobile app-based mindfulness program; a therapist-led telephone-based mindfulness program; or a web-based critical illness education program.

Results:

Among 80 patients allocated to mobile mindfulness (n= 31), telephone mindfulness (n=31), or education (n=18), 66 (83%) completed the study. For the primary outcomes, target benchmarks were exceeded by observed rates for all participants for feasibility (consent 74%, randomization 91%, retention 83%), acceptability (mean Client Satisfaction Questionnaire 27.6 [standard deviation 3.8]), and usability (mean Systems Usability Score 89.1 [SD 11.5]). For secondary outcomes, mean values (and 95% confidence intervals) reflected clinically significant group-based changes on the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (mobile (−4.8 [−6.6, −2.9]), telephone (−3.9 [−5.6, −2.2]), education (−3.0 [−5.3, 0.8]); the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (mobile −2.1 [−3.7, −0.5], telephone −1.6 [−3.0, −0.1], education −0.6 [−2.5, 1.3]), the Post-Traumatic Stress Scale (mobile −2.6 [−6.3, 1.2], telephone −2.2 [−5.6, 1.2], education −3.5 [−8.0, 1.0]), and the Patient Health Questionnaire physical symptom scale (mobile −5.3 [−7.0, −3.7], telephone −3.7 [−5.2, 2.2], education −4.8 [−6.8, 2.7]).

Conclusions:

Among ICU patients, a mobile mindfulness app initiated after hospital discharge demonstrated evidence of feasibility, acceptability, and usability and had a similar impact on psychological distress and physical symptoms as a therapist-led program. A larger trial is warranted to formally test the efficacy of this approach.

Keywords: critical illness, psychological distress, mind and body, depression, mobile app, mindfulness, psychosocial intervention

INTRODUCTION

As survival from cardiorespiratory failure has increased over time, so has the recognition that millions of patients who require treatment in intensive care units (ICUs) are left not only with physical symptoms,1–3 but with psychological long-term distress.4 As many as 66% of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) survivors report clinically important symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at 1 year post-discharge.5–8 Patients have described these symptoms in their own words as daily sources of stress, fear and foreboding, emotional disability, and social disruption.1 However, there are no effective approaches to treating this prominent component of ICU survivors’ personal experience of critical illness.1,9

In response, we recently developed a telephone-delivered mindfulness-based training program for ICU survivors, finding in an uncontrolled pilot that it was associated with improved symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.10 Mindfulness is a learned practice of non-judgmental awareness that aims to alleviate distress by uncoupling emotional reactions and habitual behavior from unpleasant symptoms, memories, thoughts, and emotions.11,12 Standard mindfulness training, typically provided face to face in group settings, has proven efficacious in improving psychological distress in various medical patient populations such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic pain.13,14 Our telephone-based approach overcame numerous feasibility barriers to in-person therapy presented by ICU survivors’ new disabilities, financial distress, and great distance from many referral centers.1,2,15,16 However, recent multi-center trials have demonstrated the challenges of scheduling and delivering psychosocial therapy effectively by telephone,17 prompting our extension of the mindfulness program to delivery through a self-directed mobile web app.

The primary purpose of this pilot randomized clinical trial (RCT) was to test the feasibility, acceptability, and usability of a novel self-directed mobile mindfulness training app in comparison to both our previous telephone-based approach as well as an ICU education program control. A secondary goal was to explore the intervention’s impact on psychological distress, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, as well as distress associated with physical symptoms. Determining if a more flexible and logistically simpler self-directed app approach has a similar impact compared to a more effort-intensive therapist-led approach is critical to planning next-step trials and also to scaling mind-body interventions for widespread use among larger populations.

METHODS

Setting, governance, and oversight

Study methodologies and reporting are guided by the 2016 CONSORT statement extension to randomized pilot and feasibility trials.18 The institutional review boards of the participating sites approved the study protocol (Online Supplement 1). An independent data safety monitoring board approved the protocol and reviewed safety at 6-month intervals.

Enrollment

Between March 1, 2016 and February 6, 2017, research coordinators screened electronic health records systems daily to identify consecutive eligible patients from adult medical, cardiac, and surgical ICUs. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18, ICU management for ≥24 hours, and cardiorespiratory failure as defined by ≥1 of these criteria: mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube for ≥12 hours; non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure for ≥4 hours in a 24-hour period; high flow nasal cannula ≥15 Liters / minute or face mask oxygen with a fractional inspired oxygen content ≥ 0.5 for ≥4 hours; or use of vasopressors, inotropes, or an aortic balloon pump for shock for ≥1 hour. Exclusions included pre-existing or current cognitive impairment, treatment for severe mental illness within 6 months of current admission, hospitalized within 3 months of current admission, active substance abuse at admission, expected survival <6 months per ICU attending physician, ICU length of stay ≥30 days, expected discharge to a location other than home, complex medical care expected soon after discharge, poor English fluency, and lack of either a reliable smartphone with a data plan or internet plus telephone access (see Online Supplement 2, pp. 1–2).

After obtaining permission from the medical team, research coordinators approached patients for written informed consent after transfer from the ICU to the ward but prior to discharge home. A self-produced 3-minute informational video was used to standardize the consent process. Patients were assigned to treatment groups immediately after completion of post-discharge Interview 1 (which included a cognition screen), targeted for completion within the first week of arrival home. A computer algorithm allocated participants at a 1.75:1.75:1 ratio (mobile, telephone, education) using simple randomization for the first 18 participants and then dynamic allocation via a method of minimization approach 19 to ensure balance across strata including: baseline Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression scale (PHQ-9) score (<15 vs. ≥15; representing a cutoff of ‘moderately severe depression symptoms’), severity of current physical symptom distress (Interview 1 Patient Health Questionnaire 15-item physical symptom scale (PHQ-15) score <10 vs. ≥10; representing a cutoff of ‘high somatic severity’), age (<50 vs. ≥50), ICU service most proximate to enrollment (medical, surgical, cardiac, neurological), and study site. An unequal allocation ratio was used to provide more experience delivering mobile and telephone mindfulness; our education program has been evaluated in a recent RCT.17 The three interventions (see Online Supplement 2, pp. 3–4) were targeted to begin immediately after group assignment.

Telephone-based mindfulness training

The goal of both mindfulness programs evaluated was to help users to be better able to manage distress related to any number of stressors, including their recent critical illness. Each week for a month, a trained psychologist (TG) delivered a ~30-minute-long telephone call composed of four previously piloted elements: brief discussion about participants’ major current stressor(s); explanation of a didactic element and the rationale for its use; practice and review;, and discussion about participant’s use of mindfulness skills, challenges in applying the skills, and how to maintain progress.10 The didactic elements included: Session 1: awareness of breathing, a core meditation technique that begins to cultivate skills of mindful, non-reactive observation; Session 2: awareness of body systems that are working well or less well as a way to continue to cultivate skills of observing, describing, and non-judgmental attention; Session 3: awareness of emotion and mindful acceptance, designed to acknowledge difficult emotions and cultivate feelings of kindness and compassion towards oneself and others; and Session 4: awareness of sound, a practice of systematically broadening awareness of senses of sound designed to be an external context to cultivate skills of observing one’s experience, letting go and practicing non-judgmental awareness. Participants were able to access group-specific complementary video and audio resources on a password-protected study website, as well as a packet of printed information.

Mobile mindfulness training

The therapist (TG) made one introductory telephone call during the patient’s first week home to explain the study rationale and to lead a brief (~10-minute) mindfulness exercise. Thereafter, the mobile app delivered all the content of the telephone mindfulness program through a 4-session guided series of videos, audio files, and interactive text features. Each weekly session included a short (4–5 minutes) background video, a 6–8-minute guided mediation (users could choose either a female or male voice), and interactive suggestions for how to apply mindfulness within their daily routine (~10 minutes). At the end of each study week, the participant was automatically prompted via email or text (as preferred) to complete the PHQ-9 depression scale survey via a secure electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePRO) system integrated with the study data system.20

Education program comparator

The goal of the self-directed web-based education program, developed and tested by our group,17 was to provide educational information about the nature and treatment of critical illness, yet no content relevant to psychological distress (see Online Supplement 2). Education participants received two brief phone calls from a research coordinator at 1 and 3 weeks post-randomization to answer general questions (e.g., troubleshooting the website).

Data collection

Participants were encouraged to self-complete all study surveys via an ePRO system accessible from automated text or email links generated by the study data system. After 6 emails (one per 48-hour period) without completion of a 1- or 3-month follow up survey, the participant was called for its completion by a clinical research coordinator. Participants were compensated $25 for each completed study procedure. Follow up was completed in June 2017.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes included feasibility, acceptability, and usability. Feasibility was assessed by comparison of observed frequencies to a priori-specified targets of informed consent among eligible patients (70%); randomization of consented participants (60%);17 retention (80%); and among participants who neither dropped out nor died, who completed all interviews (75%), completed all weekly surveys (60%; mobile group only), and completed all intervention sessions (50%). Acceptability was measured with the adapted Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ),21 which assesses credibility and satisfaction (range 9 [low] to 36 [highest]). Usability of the mobile app was assessed with open-ended participant feedback and with the 10-item System Usability Scale (SUS; 0 [lowest] to 100 [highest]).22

Secondary outcomes included psychological distress symptoms, physical symptoms, mindfulness skills, and coping. Depression symptoms were assessed with the PHQ-9, a 9-item scale (range 0 [no distress] to 27 [high distress]); symptom severity is interpreted as mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (20–27).23 Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; range 0 [no distress] to 21 [high distress]); symptom severity is interpreted as mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–21).24 The Post Traumatic Stress Scale (PTSS), a 10-item scale (range 10 [no symptoms] to 70 [high burden of symptoms]), was used to assess PTSD symptoms; >20 represents clinically important symptoms.25 We assessed quality of life using the EuroQOL 100-point visual analog scale.26 The PHQ-15 was used to measure distress associated with physical symptoms (range 0 [none] to 30 [very troublesome]).27 To evaluate possible mechanisms of intervention effects, we measured mindfulness skills with the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R), a 12-item measure of mindful qualities (range 12 [low ability] to 48 [highest ability]) 28 and coping skills with the Brief COPE (range 10 [low use] to 40 [highest use]).29 Participants were also given the opportunity to report their greatest stressor at the time of the baseline interview, and then to rate its severity at each subsequent interview (range: 0 [no stress] to 100 [high stress]). During the final survey, we elicited open-ended feedback from the app group about their experience with the program (questions shown in Online Supplement 2).

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of this pilot trial was to explore the feasibility, acceptability, and usability of mobile mindfulness to inform a definitive future clinical trial. A pragmatic sample size of 90 was chosen not based on formal power calculations, but rather because it represented a cohort large enough to inform the investigators about the potential challenges of delivering an app-based intervention in the context of post-discharge care. Contextual framing of feasibility success was performed by comparing observed vs. a priori-stated benchmark percentages by one-sample z-tests for key study milestones such as rates of attrition, adherence to telephone sessions, and interview completion across all treatment groups. Similarly, comparison of observed to benchmark means was performed using one-sample t-tests for acceptability (CSQ) and usability (SUS), as well as examination of participant feedback from post-intervention semi-structured interviews.

An additional aim was to provide meaningful 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for estimates of effect. For all distress outcomes, we estimated mean changes and corresponding CIs from baseline to each follow up for each treatment group using general linear models in SAS PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Model parameters included treatment arm, indicator variables for the two follow ups, and the treatment arm by time indicator interactions. Models were fit with a compound symmetry correlation between patients’ repeated measures. All participant data collected were included in models and analyzed according to the original group allocation. Further details, including the statistical code, are provided in Online Supplement 2, p. 6.

RESULTS

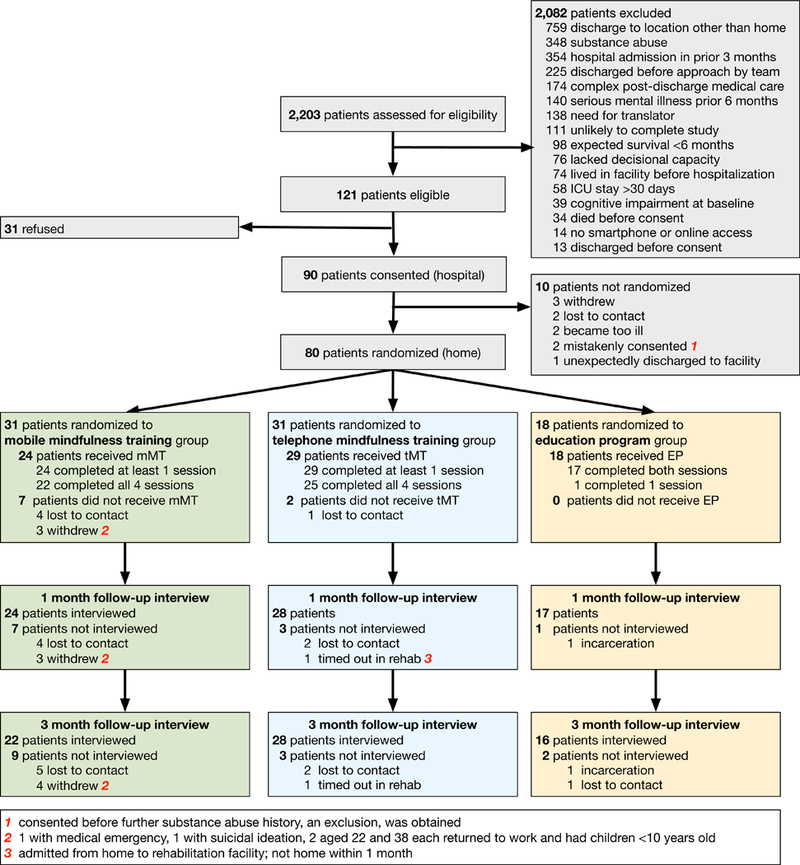

Of 121 potentially eligible patients, 90 provided informed consent during hospitalization and 80 were randomized (Site 1 n=48, 60%; Site 2 n=32, 40%) after discharge home to mobile mindfulness (n=31, 39%), telephone mindfulness (n=31, 39%), and education (n=18, 22%) (Figure 1). The cohort was middle-aged (mean age 49.5 [SD 15.1]) and mostly male (n=45, 56%), white (n=53, 66%), previously employed (n=47, 59%), admitted for a surgical or trauma diagnosis (n=55, 69%), and had a mean APACHE II score approximated a 30% expected hospital mortality rate (Table 1; see also Online Supplement 2 eTable 1 & 2). Though the mean ICU length of stay similar across groups, there was a greater frequency of shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome diagnoses in the mobile group.

Figure 1:

CONSORT diagram for flow of study participants.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients1

| Characteristics | Overall n=80 |

Mobile mindfulness n=31 |

Telephone mindfulness n=31 |

Education program n=18 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 49.5 | (15.1) | 48.7 | (15.3) | 48.1 | (16.1) | 53.3 | (12.6) |

| Female gender, no. (%) | 35 | (44) | 12 | (39) | 15 | (48) | 8 | (44) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||||||

| White | 53 | (66) | 23 | (74) | 20 | (65) | 10 | (56) |

| Black | 18 | (23) | 4 | (13) | 9 | (29) | 5 | (28) |

| Asian | 1 | (1) | 1 | (3) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 | (4) | 1 | (3) | 1 | (3) | 1 | (6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 4 | (5) | 2 | (7) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (11) |

| Missing / Unknown | 1 | (1) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (3) | 0 | (0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, no. (%) | 5 | (6) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (13) | 1 | (6) |

| Highest level of education high school or less, no. (%) | 21 | (26) | 8 | (26) | 8 | (26) | 5 | (28) |

| Employment status in month prior to hospitalization, no. (%) | ||||||||

| Working, homemaker, or student full time | 39 | (49) | 14 | (45) | 18 | (58) | 7 | (39) |

| Working part time | 10 | (13) | 4 | (13) | 3 | (10) | 3 | (17) |

| Unemployed | 5 | (6) | 2 | (7) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (17) |

| Retired | 19 | (24) | 8 | (26) | 7 | (23) | 4 | (22) |

| Disabled | 7 | (9) | 3 | (10) | 3 | (10) | 1 | (6) |

| Caring for children at home, no. (%) | 23 | (29) | 6 | (19) | 10 | (32) | 7 | (39) |

| Insurance status, no. (%) | ||||||||

| Commercial or other | 43 | (54) | 16 | (52) | 17 | (55) | 10 | (56) |

| Medicare | 17 | (21) | 5 | (16) | 8 | (26) | 4 | (22) |

| Medicaid | 15 | (19) | 8 | (26) | 4 | (13) | 3 | (17) |

| None | 5 | (6) | 2 | (7) | 2 | (7) | 1 | (6) |

| Financial distress, no. (%) | 56 | (70) | 22 | (71) | 20 | (65) | 14 | (78) |

| Chronic medical comorbidities, mean (SD) | 3.1 | (3.3) | 2.7 | (2.7) | 2.9 | (3.3) | 4.2 | (4.3) |

| Treating ICU at time of eligibility, no. (%) | ||||||||

| Medicine | 25 | (31) | 10 | (32) | 9 | (29) | 10 | (56) |

| Surgery | 55 | (69) | 21 | (68) | 22 | (71) | 8 | (44) |

| APACHE II score on day of enrollment, mean (SD) | 17.9 | (6.8) | 18.2 | (6.7) | 16.9 | (5.5) | 18.9 | (8.9) |

| Taking at the time of hospital admission, no. (%) 2 | ||||||||

| Antidepressants | 18 | (23) | 6 | (19) | 7 | (23) | 3 | (17) |

| Anxiolytics | 11 | (14) | 3 | (10) | 5 | (16) | 2 | (11) |

| Other psychiatric medication | 1 | (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (0) | 1 | (6) |

| Narcotics | 12 | (15) | 4 | (13) | 5 | (16) | 3 | (17) |

| Prescribed at the time of hospital discharge, no. (%) 2 | ||||||||

| Antidepressants | 16 | (20) | 6 | (19) | 5 | (16) | 5 | (28) |

| Anxiolytics | 10 | (13) | 3 | (10) | 4 | (13) | 3 | (17) |

| Other psychiatric medication | 1 | (1) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (6) |

| Narcotics | 50 | (63) | 19 | (61) | 21 | (68) | 10 | (56) |

Expanded table in Online Supplement 2

Multiple responses possible

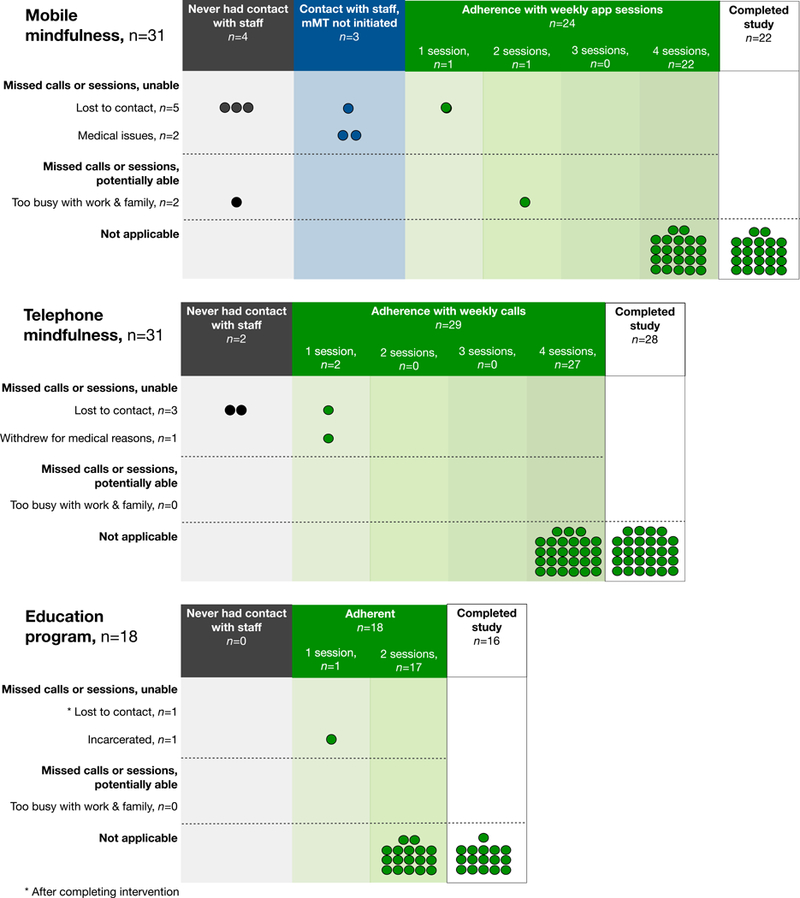

A total of 190 (88%) of 215 possible data collections were done online via self-report, while the remainder were completed by telephone interviews. Observed primary outcome metrics of feasibility, acceptability, and usability met or exceeded benchmark targets (Table 2). A total of 66 randomized patients completed the study, representing 83% overall and 89% of those with any post-discharge contact with study staff. Loss to contact and withdrawal were more common in the mobile mindfulness group, although 7 (78%) of the 9 lost to contact never initiated the intervention (Figure 2). Among the 24 mobile mindfulness patients who initiated the app, 93 of 96 (97%) possible weekly app sessions were completed; 22 (92%) completed all 4 app sessions and all 4 weekly surveys as determined by app analytics. Similarly, 27 (93%) of telephone and 17 (94%) of education patients completed all intervention sessions. Mean CSQ (27.6 [SD 3.8]) and SUS (86.5 [SD 13.3]) scores demonstrated strong acceptability and usability, findings complemented by generally positive participant feedback (Online Supplement 2 eTable 4).

Table 2:

Feasibility, acceptability, and usability.

| Target % or mean |

All patients n (%) or mean (SD) |

Mobile mindfulness n (%) or mean (SD) |

Telephone mindfulness n (%) or mean (SD) |

Education program n (%) or mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility | |||||

| Eligible participants who consented | ≥70% | 90 (74%) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Consented participants who were randomized | ≥60% | 80 (91%) 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Randomized participants who dropped out Overall Before intervention initiated After intervention initiated |

≤20% |

14 (18%) 9 (64%) 5 (36%) |

9 (29%) 7 (78%) 2 (22%) |

3 (10%) 2 (66%) 1 (34%) |

2 (11%) 0 2 (100%) |

| Participants who completed all interviews 2 | ≥75% | 66 (83%) | 22 (71%) | 28 (90%) | 16 (89%) |

| Participants who completed all weekly surveys 2 | ≥60% | n/a | 17 (89%) | n/a | n/a |

| Participants who completed all intervention sessions 2 | ≥50% | n/a | 22 (92%) | 27 (93%) | 17 (94%) |

| Acceptability | |||||

| CSQ score, mean 3 | ≥10 | 27.9 (3.7) | 27.6 (3.8) | 29.4 (3.3) | 25.7 (3.2) |

| Usability | |||||

| SUS score, mean 4 | ≥80 | n/a | 86.5 (13.3) | n/a | n/a |

| Number of participant clicks on website 5 | n/a | n/a | 188.4 (220.8) | n/a | n/a |

Denominator is 88 because of 2 consented who mistakenly met exclusion criteria; see Figure 2

Among eligible participants who neither dropped out nor died

CSQ = Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

SUS = Systems Usability Scale.

Using Google analytics; also see Online Supplement 2

Figure 2: Patient intervention adherence and study completion by treatment group.

This figure displays adherence status as well as reasons for non-adherence by treatment group as well as reasons for missed sessions for all study groups. Each circle represents one patient. The number of sessions completed by each patient is indicated on the horizontal axis.

The full cohort demonstrated mild baseline symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as mild to moderate PTSD symptoms that did not differ by group assignment (Table 3; see also Online Supplement eTables 5 and 6).31 In comparison to the education program (−3.0 [95% confidence interval −5.3, −0.8]), reductions in mean PHQ-9 scores were similar between mobile mindfulness (−4.8 [−6.6, −2.9]) and telephone (−3.9 [−5.6, −2.2]) groups at 3 months. This similar impact was consistent across the GAD-7 (mobile mindfulness −2.1 [−3.7, −0.5]; telephone −1.6 [−3.0, −0.1]), PTSS (mobile mindfulness −2.6 [−6.3, 1.2]; telephone −2.2 [−5.6, 1.2]), and PHQ-10 (mobile mindfulness −5.3 [−7.0, −3.7]; telephone −3.7 [−5.2, −2.2]); see also Online Supplement 2 eFigure 1. Among education recipients in comparison to the mindfulness groups, there was numerically less impact seen on PHQ-9 (−3.0 [−5.3, −0.8]) and GAD-7 (−0.6 [−2.5,1.3]) scores at 3 months, though similar changes on the PTSS score (−3.5 [−8.0, 1.0]). The CAMS-R and Brief COPE did not appear responsive to change. Participants’ severity ratings for self-named stressors, generally focused on physical and functional concerns, did not improve in any treatment group (see Online Supplement 2 eTable 3).

Table 3:

Model-estimated means and mean differences over time in psychosocial outcomes between groups

| Model-estimated means (SE) 1 | Mean change from baseline (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome and time point |

Education4 | Mobile mindfulness5 |

Telephone mindfulness6 |

Education | Mobile mindfulness |

Telephone mindfulness |

| PHQ-9 2 | ||||||

| Baseline | 7.1 (1.1) | 8.2 (0.8) | 7.6 (0.8) | |||

| 1 month | 5.8 (1.1) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.6 (1.4) | −1.3 (−3.5, 0.9) |

−3.8 (−5.6, −1.9) |

−2.4 (−4.2, −0.7) |

| 3 months | 4.0 (1.1) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.4) | −3.0 (−5.3, −0.8) |

−4.8 (−6.6, −2.9) |

−3.9 (−5.6, −2.2) |

| GAD-7 2 | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.7) | 5.1 (0.7) | |||

| 1 month | 4.1 (1.0) | 3.4 (0.8) | 2.8 (1.2) | −0.4 (−2.3,1.5) |

−1.4 (−3.0,0.1) |

−1.7 (−3.1, −0.2) |

| 3 months | 3.9 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.9 (1.2) | −0.6 (−2.5,1.3) | −2.1 (−3.7, −0.5) |

−1.6 (−3.0, −0.1) |

| PTSS 2 | ||||||

| Baseline | 21.4 (2.4) | 22.1 (1.9) | 21.9 (1.9) | |||

| 1 month | 20.4 (2.5) | 20.5 (2.0) | 19.7 (3.0) | −1.0 (−5.4,3.5) | −1.7 (−5.3, 2.0) |

−1.7 (−5.2, 1.7) |

| 3 months | 17.9 (2.5) | 19.6 (2.1) | 19.2 (3.0) | −3.5 (−8.0,1.0) | −2.6 (−6.3, 1.2) |

−2.2 (−5.6, 1.2) |

| PHQ-10 2 | ||||||

| Baseline | 11.0 (0.9) | 10.1 (0.7) | 10.1 (0.7) | |||

| 1 month | 7.6 (0.9) | 6.9 (0.8) | 8.4 (1.2) | −3.4 (−5.4, −1.5) |

−3.1 (−4.8, −1.5) |

−2.6 (−4.1, −1.1) |

| 3 months | 6.3 (1.0) | 4.7 (0.8) | 7.3 (1.2) | −4.8 (−6.8, −2.7) |

−5.3 (−7.0, −3.7) |

−3.7 (−5.2, −2.2) |

| QOL VAS 3 | ||||||

| Baseline | 71.8 (4.3) | 80.4 (3.3) | 74.3 (3.3) | |||

| 1 month | 72.5 (4.4) | 72.9 (3.7) | 72.6 (5.7) | 0.7 (−8.6, 9.9) |

−7.5 (−15.1, 0.2) |

0.8 (−6.4,8.0) |

| 3 months | 72.5 (4.5) | 77.6 (3.8) | 75.0 (5.7) | 0.7 (−8.9, 10.1) |

−2.7 (−10.6, 5.1) |

3.2 (−4.0,10.4) |

| CAMS-R 3 | ||||||

| Baseline | 30.1 (1.5) | 31.9 (1.1) | 31.2 (1.1) | |||

| 1 month | 30.0 (1.5) | 31.0 (1.2) | 28.7 (1.8) | −0.1 (−2.9, 2.6) |

−0.9 (−3.2, 1.3) |

−1.4 (−3.5, 0.8) |

| 3 months | 28.8 (1.5) | 32.6 (1.3) | 29.2 (1.8) | −1.3 (−4.1, 1.5) |

0.7 (−1.7, 3.0) |

−0.9 (−3.1, 1.3) |

| Brief COPE 3 | ||||||

| baseline | 13.8 (1.0) | 14.5 (0.7) | 13.0 (0.7) | |||

| 1 month | 13.1 (1.0) | 14.6 (0.8) | 15.2 (1.2) | −0.8 (−2.5, 1.0) |

0.05 (−1.4,1.5) |

1.4 (0.04, 2.7) |

| 3 months | 13.6 (1.0) | 14.1 (0.8) | 15.2 (1.2) | −0.2 (−2.0, 1.6) |

−0.5 (−1.9, 1.0) |

1.3 (−0.03, 2.7) |

Based on general linear models; no adjustment for covariates. Model estimated means are based on all patients, not just those with observations at 1 and 3 months.

Negative scores represent improvement

Positive scores represent improvement

n=18 at baseline, n=17 at 1 month, and n=16 at 3 months

n=31 at baseline, n=24 at 1 month, and n=22 at 3 months

n=31 at baseline, n=28 at 1 month, and n=28 at 3 months

PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item depression scale); GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale); PTSS (Post-Traumatic Stress Scale); PHQ-10 (Patient Health Questionnaire 10-item physical symptom scale); QOL VAS (quality of life 100-point visual analog scale); CAMS-R (Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised Mindfulness instrument); Brief COPE (Brief coping inventory).

In the mobile mindfulness group, the frequency and duration of app use correlated with improvement in distress symptoms (see Online Supplement 2 eTables 6 and 7). For example, depression symptom improvement (i.e., PHQ-9 score change) was correlated with number of pages viewed per session (r=−0.54), number of screen clicks per app session (r=−0.49), and number of app sessions viewed overall (r=−0.46). Depression symptom improvement had a stronger correlation with activity in the later stages of the intervention (r=−0.42 [week 4]) compared to earlier stages (r = 0.02 [week 1]).

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter pilot RCT, we found support for the feasibility, acceptability, usability, and impact on psychological distress of a novel self-directed mindfulness training program delivered by a mobile app. Importantly, mobile mindfulness performed similarly to therapist-led mindfulness training program and generally better than an education program. Mobile mindfulness therefore appears to show promise as a scalable patient-centered approach to addressing ICU survivors’ widely prevalent psychological distress that can also overcome many post-discharge access to care barriers these patients experience.

As mindfulness grows in general popularity and evidence accrues for its efficacy,32–35 the delivery of mindfulness content by a mobile web app accessible on any digital device could become an attractive approach for providers and patients alike. The self-directed (though app-guided) nature of mobile mindfulness meets many patients’ stated preference for convenience and flexibility at a time when they are re-entering home, work, and family demands while also navigating recovery from a life-threatening condition.36 It is important to note that adherence and retention for mobile mindfulness was substantially higher than that observed in a recent telephone-based coping skills training program for ICU survivors of similar length.17 From the trialist perspective, a self-directed therapy overcomes logistical barriers associated with telephone-based interventions delivered from unfamiliar area codes to patients spread across multiple time zones.

This RCT also provides numerous lessons about how to improve mobile mindfulness and its delivery. First, though participants’ feedback on the app was positive, patients’ constructive feedback highlighted targets for further enhancing usability including more interactive features and enhanced visualization of progress over time. Our data closely linking the frequency, quality, and duration of app use with reduction in depression symptoms demonstrates the importance of optimizing user engagement as a means to improve adherence, retention, dose, and effect.37,38

Second, while the self-directed mobile mindfulness had a favorable effect on symptoms, uncommon for a comparative web-based therapy,37,39 the telephone group had slightly better adherence and retention. Though the retention of participants is significantly better than that observed in a similarly structured mobile coping skills training intervention conducted among ICU patients,17 further study is required to understand the two approaches’ possible tradeoffs (e.g., personalization, dose, costs, scalability), as well as to determine the value of an initial motivational interview at kickoff or targeted therapist interaction during the mobile intervention (e.g., non-responders with persistent or increasing symptoms over time).40

Third, some study design elements that may have diluted the comparative effects of mobile mindfulness. Patients were randomized regardless of distress level,41 similar to recent approaches, because we hypothesized that distress may increase during follow up due to persistent financial, social, and medical stressors. However, in a recent RCT we found a concentration of psychosocial intervention effect among only ICU survivors with elevated baseline distress.11 That trial also showed that the ICU survivor-specific education control also used in the current mindfulness trial had an active effect on 3-month distress. Furthermore, despite less improvement in distress compared to the mobile mindfulness group, the education group had a lower prevalence of shock and ARDS and returned to normal duties over two weeks earlier. Last, the relatively mild baseline distress across groups may have contributed to an impact-limiting floor effect.

This pilot study has notable limitations. First, the small sample limits the precision and the generalizability of results as well as our ability to understand the impact of clinical and demographic variables. Second, while the results are compelling, this pilot study was not designed to evaluate efficacy. Third, though post-randomization dropout was higher in the mobile mindfulness group, most of it occurred before patients either had contact with study staff or used the app. While likely due to chance, the small sample size limits a better understanding of differential attrition. Last, while there is not clear consensus about an optimal duration for a mindfulness program, our strategy that emphasized convenience, a relatively brief period of daily guided meditation (10 minutes), and a brief intervention duration is shorter than most.42 However, short durations can be effective 35 and may be an attractive way to foster self-care behaviors for this unique population.

CONCLUSIONS

A self-directed, four-session post-discharge mindfulness program for ICU survivors delivered by a mobile app was feasible, acceptable, usable, and demonstrated evidence for impact on psychological distress that was similar to a therapist-delivered mindfulness program. Further study is warranted to understand the mobile app’s most impactful elements, to further optimize its usability, and to determine its long-term efficacy.

Supplementary Material

What is the key question?

Is a novel, self-directed app a feasible and acceptable approach to overcoming barriers to addressing psychological distress among ICU survivors—and work similarly to telephone-based therapy?

What is the bottom line?

A self-directed mobile mindfulness program was feasible, well-accepted, and appeared to reduce psychological and physical symptoms similarly to a telephone-based mindfulness program and better than an education program.

Why read on?

This study highlights numerous issues in the design and conduct of trials designed to reduce psychological distress among ICU survivors that are relevant to both clinicians and researchers alike.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the patients who participated, the intensive care unit staffs of Duke and Harborview, Brenda Walton, Brian Fischer and the Smashing Boxes programming team, Shelley Epps, the Duke Institutional Review Board, and the Data Safety Monitoring Board (Judson Brewer, Samuel Brown, and Ofer Harel).

Funding source: This research was made possible by a grant to Dr. Cox from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (R34 AT008819).

Dr. Olsen was also supported by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410) at the Durham VA Medical Center.

This research was conducted at Duke University Medical Center and the University of Washington / Harborview Medical Center.

Study design and concept: CEC, LSP, JMG, CLH, TG, DMJ, AU

Writing and review: CEC, LSP, JMG, TG, DMJ, WR, MDK, CLH, AU

Analyses: MKO, LS, CEC

Obtaining data: DMJ, AU, WR, MDK

Acquisition of funding: CEC

Final approval: CEC, LSP, JMG, TG, DMJ, WR, MDK, CLH, AU

Accountable for all aspects of work: CEC

Footnotes

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02701361.

Conflicts of interest: No authors have either competing financial or non-financial interests in this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cox CE, Docherty SL, Brandon DH, et al. Surviving critical illness: acute respiratory distress syndrome as experienced by patients and their caregivers. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2702–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wunsch H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychoactive medication use among nonsurgical critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA 2014;311:1133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown SM, Wilson EL, Presson AP, et al. Understanding patient outcomes after acute respiratory distress syndrome: identifying subtypes of physical, cognitive and mental health outcomes. Thorax 2017;72:1094–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang M, Parker AM, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychiatric Symptoms in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors: A 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Crit Care Med 2016;44:954–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med 2015;43:642–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive Symptoms After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1744–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory medicine 2014;2:369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox CE, Porter LS, Buck PJ, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based mindfulness training intervention for survivors of critical illness. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabat-Zinn J Full catastrophe living. New York, NY: Delta Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA 2008;300:1350–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ornbol E, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:102–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, et al. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Herridge MS, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. The RECOVER Program: Disability Risk Groups and 1-Year Outcome after 7 or More Days of Mechanical Ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:831–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long AC, Kross EK, Davydow DS, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors of critical illness: creation of a conceptual model addressing identification, prevention, and management. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox CE, Hough CL, Carson SS, et al. Effects of a Telephone- and Web-based Coping Skills Training Program Compared with an Education Program for Survivors of Critical Illness and Their Family Members. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:66–78. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, et al. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials. a review. Control Clin Trials 2002;23:662–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox CE, Wysham NG, Kamal AH, et al. Usability Testing of an Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome System for Survivors of Critical Illness. Am J Crit Care 2016;25:340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann 1982;5:233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooke J A quick and dirty usability scale In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, et al. , eds. Usability evaluation in industry. London: Taylor and Francis 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a screening test to document traumatic experiences and to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder in ARDS patients after intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med 1999;25:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EuroQol G EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002;64:258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, et al. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2007;29:177–90. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 1997;4:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girard TD, Shintani AK, Jackson JC, et al. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms following critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2007;11:R28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Black DS, O’Reilly GA, Olmstead R, et al. Mindfulness meditation and improvement in sleep quality and daytime impairment among older adults with sleep disturbances: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:1240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Veterans: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015;314:456–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu M, Purdon C, Seli P, et al. Mindfulness and mind wandering: The protective effects of brief meditation in anxious individuals. Conscious Cogn 2017;51:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax 2018;73:125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spijkerman MP, Pots WT, Bohlmeijer ET. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;45:102–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Services DoHaH. Research-Based Web Design & Usability Guidelines, 2013.

- 39.Toivonen KI, Zernicke K, Carlson LE. Web-Based Mindfulness Interventions for People With Physical Health Conditions: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, et al. Tailoring mind-body therapies to individual needs: patients’ program preference and psychological traits as moderators of the effects of mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy in distressed breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014;2014:308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt K, Worrack S, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of a Primary Care Management Intervention on Mental Health-Related Quality of Life Among Survivors of Sepsis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:2703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmody J, Baer RA. How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:627–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.