Abstract

Background and purpose — International comparisons of total hip arthroplasty (THA) practices and outcomes provide an opportunity to enhance the quality of care worldwide. We compared THA patients, implants, techniques, and survivorship in Sweden, Australia, and the United States.

Patients and methods — Primary THAs due to osteoarthritis were identified using Swedish (n = 159,695), Australian (n = 279,693), and US registries (n = 69,641) (2003–2015). We compared patients, practices, and implant usage across the countries using descriptive statistics. We evaluated time to all-cause revision using Kaplan–Meier survival curves. We assessed differences in countries’ THA survival using chi-square tests of survival probabilities.

Results — Sweden had fewer comorbidities than the United States and Australia. Cement fixation was used predominantly in Sweden and cementless in the United States and Australia. The direct anterior approach was used more frequently in the United States and Australia. Smaller head sizes (≤ 32 mm vs. ≥ 36 mm) were used more often in Sweden than the United States and Australia. Metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene was used more frequently in the United States and Australia than in Sweden. Sweden’s 5- (97.8%) and 10-year THA survival (95.8%) was higher than the United States’ (5-year: 97.0%; 10-year: 95.2%) and Australia (5-year: 96.3%; 10-year: 93.5%).

Interpretation — Patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and implants differed across the 3 countries, emphasizing the need to adjust for demographics, surgical techniques, and implants and the need for global standardized definitions to compare THA survivorship internationally.

Arthroplasty registries provide a mechanism for evaluating patient, surgical, and implant characteristics associated with revision surgery (Paxton et al. 2012, 2015, Khatod et al. 2014) and to identify clinical best practices for enhancing quality of care (Herberts and Malchau 1999, 2000, Graves 2010, Paxton et al, 2010, 2012). In addition, identification of variations between countries provides an opportunity to evaluate similarities and differences in practices and outcomes. Investigation of total hip arthroplasty (THA) variation between countries has been examined in Scandinavia (Havelin et al. 2011, Makela et al. 2014) but has been limited in other countries. However, with an increased focus on the need for worldwide evidence on THA implant performance, international collaborations have increased (Sedrakyan et al. 2011, 2014). Despite an increased focus on such collaborations, variations in US, Australian, and Swedish THA patients, practices, and outcomes have not been fully examined. Therefore, we investigated similarities and differences in patient characteristics, surgical techniques, implant selection, and implant survival rates in THA patients across the 3 countries to identify future areas of research based on the country comparisons.

Patients and methods

Primary THAs due to osteoarthritis were identified using national and regional registries in Sweden (n = 159,695) (SHAR 2014), Australia (n = 279,693) (AOANJRR 2015), and the United States (Paxton et al. 2012) (n = 69,641) from 2003 to 2015. The capture rate of these registries exceeds 95% and loss to follow-up is less than 8% over the study period. Validation and quality control methods of these registries have been previously published (Soderman et al. 2000, Paxton et al. 2010, 2012, AOANJRR 2016). Bilateral procedures were included in the study. Hip resurfacing procedures were excluded.

Patient characteristics (i.e., age, sex, BMI, ASA score), surgical techniques (i.e., surgical approach, type of cement fixation), implant types (i.e., bearing surface, femoral head size), and 5- and 10-year implant survival were reported from the registries. Sweden’s BMI and ASA were available from 2008 to 2015. Australia’s BMI was available only for 2015 and their ASA scores from 2012 to 2015. For the US cohort, BMI and ASA were available for the entire time period. Tables with aggregate-level data were shared across countries. Descriptive statistics were used to compare and contrast patients, practices, and implant usage. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to evaluate time to all-cause revision across the countries. Chi-square tests of survival probabilities were used to assess differences in THA survival probabilities between the countries at 5- and 10-year follow-up. 95% confidence intervals (CI) are also presented.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Approval from the Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to the start of this study (#5488 approved on August 27, 2009) and from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (entry number 271-14 approved on April 7, 2014 with amendment T-609-17 approved on July 10, 2017). There is no funding. There are no conflicts of interest.

Results

Incidence rates of primary THA

The volume of primary THAs for OA increased each year in all 3 countries during the study period. The 2015 incidence rates of THA with an OA diagnosis were higher in Australia and Sweden then in the US cohort (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

Patient characteristics

THA sex was predominantly female in all 3 countries. However, Australia had a higher proportion of males than the US and Swedish cohorts. The US cohort was younger than both Australian and Swedish cohorts. Sweden had the lowest proportion of obese patients and lowest ASA scores of the 3 cohorts (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

Surgical techniques

Cement fixation was used predominantly in Sweden while cementless fixation was used more frequently in the United States and Australia. The percentage of hybrid fixation was higher in Australia than for the US cohort and in Sweden. The posterior approach was the main surgical approach for all countries. However, the direct anterior approach used in Australia and the United States was not adopted in Sweden during the study period (Tables 3 and 4, see Supplementary data).

Implant characteristics

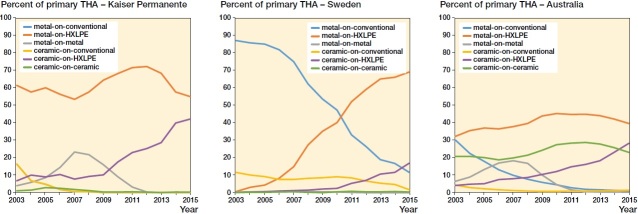

While metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene (HXLPE) was used more frequently in the United States and Australia, metal-on-conventional bearing surface was used more often in Sweden, especially during the early part of the period studied. Ceramic-on-ceramic was used more frequently in Australia and rarely in Sweden. Ceramic-on-HXLPE was used more frequently in the US cohort (Table 4, see Supplementary data). In all countries, metal-on-metal bearing surfaces decreased, in Sweden from a few hundred to zero. In all 3 countries, the use of ceramic-on-HXLPE increased during the study period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

THA implant bearing surfaces by country.

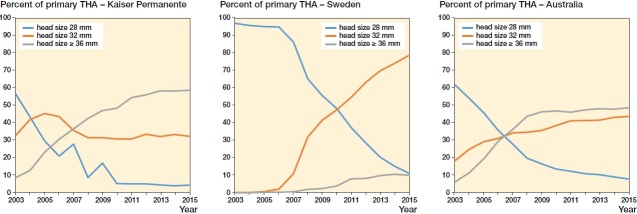

Femoral head size

Femoral head size use differed across countries with Sweden using smaller head sizes (i.e., ≤ 28 mm and 32 mm) whereas the US and Australian cohorts had a greater proportion of 36 mm and larger head sizes (Table 4). The use of 32 mm femoral head size became more prominent in Sweden during the study period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

THA implant head size by country.

Hospital annual volume

Hospital volume was similar across US and Swedish cohorts. However, Australia had a higher percentage of low volume facilities compared with the United States and Sweden (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Outcomes

THA survival at 5 years was higher in Sweden (97.8%, CI 97.8–97.9) than the US (97.0%, CI 96.7–97.2), and Australian (96.3%, CI 96.2–96.4) cohorts. The US cohort had a higher 5-year THA survivorship than the Australian.

THA survival at 10 years was higher in Sweden (95.8%, CI 95.6–95.9) than for the US cohort (95.2%, CI 94.7–95.6) and in Australia (93.5%, CI 93.4–93.7). The US cohort had a higher 10-year THA survivorship than Australia (Table 6, Figure 3, see Supplementary data).

The most frequent reasons for revisions differed across the countries. Aseptic loosening was higher in Sweden along with infection (Figure 4, see Supplementary data). Instability was a more common reason for revision in the US cohort than in Sweden and Australia.

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of US, Swedish, and Australian THA practice patterns and outcomes, and identifies variation between countries in patient characteristics, fixation, implant characteristics, and THA implant survival.

Patient characteristics

First, the study highlights variation in the incidence of primary THA for OA with Sweden and Australia having a higher annual incidence rate than the US cohort. Our findings are consistent with other reports of variation in international total hip incidence rates (Merx et al. 2003). Differences in incidence rates may reflect the younger population in the US health system, an actual variation in diagnoses leading to THA, differences in diagnostic accuracy and indications for surgical treatment, varying access to care in the different healthcare systems, or possibly variation in population demand.

Second, patient characteristics appear to differ across countries with Sweden reporting lower BMI and ASA scores than Australia and the United States. This finding is consistent with other studies that have indicated a higher BMI in the US population (ProCon.org 2011). Differences in ASA scores could reflect a healthier population in Sweden but could also represent variations in coding practices across the countries. In addition to differences in BMI and comorbidities, cohorts also differed in age distribution with the US group having a younger THA population. This may reflect differences in thresholds for operating on younger patients or varying access to care across the different healthcare systems. The differences in patient characteristics emphasize the need to adjust for this variation when examining THA outcomes across countries.

Surgical techniques

Although the posterior approach was used most frequently in all 3 countries, Sweden did not utilize the direct anterior approach. Several systematic reviews and registry studies suggest that the anterior approach is associated with lower dislocation and revision rates (Barrett et al. 2013, Higgins et al. 2015, Sheth et al. 2015, Miller et al. 2018a, b). However, these studies focused on short-term and functional outcomes without any certain conclusions concerning longer term revision rates. Despite differences in surgical approaches, Sweden had lower THA revision rates than the US cohort and Australia.

Fixation and implant characteristics

Another identified difference was type of THA fixation used in the different countries. While Sweden used cement fixation more frequently, US and Australian practices were predominantly cementless. Studies examining fixation seem to suggest an advantage for cement fixation, especially in older patients (SHAR 2009, Hailer et al. 2010, AOANJRR 2017, Phedy et al. 2017). Future studies comparing international variations should account for fixation types and implants to fully evaluate differences in THA implant survival.

Type of THA bearing surface also differed across countries with Sweden adopting more metal-on-conventional polyethylene. Several large registry studies have identified a higher revision rate in metal-on-conventional bearing surface than metal-on-HXLPE (AOANJRR 2013, Paxton et al. 2015). However, this difference may be prosthesis-dependent (Johanson et al. 2017). Sweden’s use of metal-on-conventional has decreased and the use of metal-on-HXLPE increased during the study period. Sweden also adopted less large head size metal-on-metal, which has been reported as having a higher risk of THA revision (AOANJRR 2008). The use of large head size metal-on-metal decreased in both the United States and Australia. In all 3 countries, the use of ceramic-on-HXLPE bearing surface increased. While the Australian registry reports lower revision rates in ceramic-on-HXLPE compared with metal-on-HXLPE, a recent US study indicated similar revision rates among these bearing surfaces but higher dislocation rates in ceramic versus metal femoral heads of < 32 mm, suggesting both head size and bearing surface material influence risk of revision (AOANJRR 2017, Cafri et al. 2017).

Hospital volume

Annual hospital volume also differed across countries. While hospital volumes were similar in Sweden and the US cohort, the Australian registry had a higher number of cases performed at low-volume hospitals. Lower hospital volume has been identified in relationship to higher complication rates and readmissions (Dy et al. 2014, Laucis et al. 2016, Sibley et al. 2017). Evaluating further the effects of hospital volume may identify potential areas of focus for quality improvement within healthcare systems.

THA survival

In evaluating THA survival, all 3 countries had 5- and 10-year THA implant survival estimates above 95%. 5- and 10-year implant survival was highest in Sweden and lowest in Australia. Differences in survival could possibly be related to different thresholds for revision THA surgery in those countries. Most likely, however, the difference THA survival is related to the degree of variation in implant selection between the countries. While Sweden and the US cohort used a limited number of implants during this timeframe, Australia had much greater variation in THA implant models. In Australia alone, over 2,000 cup and stem combinations were used. 78 different THA acetabular cups and stem model combinations have been used with 10-year follow-up and cumulative percentage revision rates ranging from 2% to 46%. Only 35% of these combinations had less than a 5% 10-year cumulative percentage revision (AOANJRR 2017). In comparison, Sweden’s 10-year THA survival ranged from 94.4% to 98.1% based on a more restricted use of cup/stem combinations. In Sweden, 6 stems and 15 cups accounted for over 90% of the implant usage (SHAR 2016). This suggests that implant selection plays a key role in THA survival. The comparison of specific implant performance in similar patients with similar techniques must be evaluated to understand the underlying source of this international variation in THA survival.

In addition to differences in revision rates, the reasons for revision also differed across countries. Sweden had a higher percentage of aseptic loosening than the US and Australian cohorts, which could be related to the higher percentage of metal-on-conventional polyethylene use in Sweden during the study period. The US cohort had a higher percentage of pain as the revision diagnosis. Revision due to pain and aseptic loosening combined in the US group was comparable to aseptic loosening diagnosis in both Sweden and Australia, suggesting aseptic loosening maybe the underlying diagnosis of pain in the US cohort. Revision diagnosis of infection was higher in Sweden than in the other countries. The US cohort had a higher rate of revision due to instability despite the use of larger femoral head sizes and the direct anterior approach. This most likely reflects the predominant use of uncemented cups in the US cohort, which has been reported to have more instability than cemented cups (Conroy et al. 2008). Differences in revision diagnoses may be related to the different underlying mechanisms of failure related to different implant usage and indications but could also be related to variation in surgeon documentation and definitions across registries, again emphasizing the need for standardized, global revision definitions to conduct international comparisons of THA outcomes.

This study has both strengths and limitations. The strengths of this study include the large registry data sets with high-quality data and minimal loss to follow-up. In addition, registries provide real-world data with high generalizability/external validity. Limitations include the descriptive nature of the study, which has not been adjusted for confounders, the observational study design limiting causality, and the use of only one US integrated healthcare system. In addition, although countries differed in patient, implant, and surgical factors, the difference in THA survival may be interpreted as not being clinically relevant due to the small differences. However, this study emphasizes there are differences in THA survival overall and further research needs to be conducted to evaluate THA outcomes by specific types of prostheses while controlling for patient, surgical, and hospital factors.

In summary, patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and implant selection differs across the 3 countries, emphasizing the need to address regional and national differences in demographics, surgical techniques, implants, and the need for global standardized definitions to compare results across existing registries and to develop international THA benchmarking standards.

Supplementary data

Tables 1–6 and Figures 3–4 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2019.1574395

Supplementary Material

Notes and Acknowledgements

EP: conception of study, interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. SN, JK, HM, SG, RS, OR: interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. ML, GC: statistical analyses, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation.

Acta thanks Antti Eskelinen and Sarunas Tarasevicius for help with peer review of this study.

References

- AOANJRR Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Register Annual Report. Adelaide, SA, Australia; 2008, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports-2017.

- Barrett W P, Turner S E, Leopold J P. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28(9): 1634–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafri G, Paxton E W, Love R, Bini S A, Kurtz S M. Is there a difference in revision risk between metal and ceramic heads on highly crosslinked polyethylene liners? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475(5): 1349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy J L, Whitehouse S L, Graves S E, Pratt N L, Ryan P, Crawford R W. Risk factors for revision for early dislocation in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(6): 867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dy C J, Bozic K J, Pan T J, Wright T M, Padgett D E, Lyman S. Risk factors for early revision after total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(6): 907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves S E. the value of arthroplasty registry data. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 8–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer N P, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I, Robertsson O, Fenstad A M, Overgaard S, Garellick G, Furnes O. A Scandinavian experience of register collaboration: the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(Suppl 3): 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts P, Malchau H. Many years of registration have improved the quality of hip arthroplasty. Läkartidningen 1999; 96(20): 2469–73, 75-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberts P, Malchau H. Long-term registration has improved the quality of hip replacement: a review of the Swedish THR Register comparing 160,000 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(2): 111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins B T, Barlow D R, Heagerty N E, Lin T J. Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(3): 419–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson P E, Furnes O, Ivar Havelin L, Fenstad A M, Pedersen A B, Overgaard S, Garellick G, Makela K, Karrholm J. Outcome in design-specific comparisons between highly crosslinked and conventional polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2017; 88(4): 363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatod M, Cafri G, Namba R S, Inacio M C, Paxton E W. Risk factors for total hip arthroplasty aseptic revision. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(7): 1412–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laucis N C, Chowdhury M, Dasgupta A, Bhattacharyya T. Trend toward high-volume hospitals and the influence on complications in knee and hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98(9): 707–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela K T, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Garellick G, Ranstam J, Eskelinen A. Countrywise results of total hip replacement: an analysis of 438,733 hips based on the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association database. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(2): 107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merx H, Dreinhofer K, Schrader P, Sturmer T, Puhl W, Gunther K P, Brenner H. International variation in hip replacement rates. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62(3): 222–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L E, Gondusky J S, Bhattacharyya S, Kamath A F, Boettner F, Wright J. Does surgical approach affect outcomes in total hip arthroplasty through 90 days of follow-up? A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2018a; 33(4): 1296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L E, Gondusky J S, Kamath A F, Boettner F, Wright J, Bhattacharyya S. Influence of surgical approach on complication risk in primary total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2018b; 89(3): 289–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Khatod M, Yue E J, Namba R S. Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry: aligning operations with information technology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468(10): 2646–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Kiley M L. The Kaiser Permanente Implant Registries: effect on patient safety, quality improvement, cost effectiveness, and research opportunities. Perm J 2012; 16(2): 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Khatod M, Yue E J, Funahashi T, Barber T. Risk calculators predict failures of knee and hip arthroplasties: findings from a large health maintenance organization. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(12): 3965–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phedy P, Ismail H D, Hoo C, Djaja Y P. Total hip replacement: a meta-analysis to evaluate survival of cemented, cementless and hybrid implants. World J Orthop 2017; 8(2): 192–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ProCon.org US and global obesity levels: the fat chart. Santa Monica, CA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sedrakyan A, Paxton E W, Phillips C, Namba R, Funahashi T, Barber T, Sculco T, Padgett D, Wright T, Marinac-Dabic D. The International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries: overview and summary. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(Suppl 3): 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedrakyan A, Paxton E, Graves S, Love R, Marinac-Dabic D. National and international postmarket research and surveillance implementation: achievements of the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries initiative 2014. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(Suppl): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAR Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2009. https://shpr.registercentrum.se/shar-in-english/annual-reports-from-the-swedish-hip-arthroplasty-register/p/rkeyyeElz.

- SHAR Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2014. https://shpr.registercentrum.se/shar-in-english/annual-reports-from-the-swedish-hip-arthroplasty-register/p/rkeyyeElz.

- SHAR Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2016. https://shpr.registercentrum.se/shar-in-english/annual-reports-from-the-swedish-hip-arthroplasty-register/p/rkeyyeElz.

- Sheth D, Cafri G, Inacio M C, Paxton E W, Namba R S. Anterior and anterolateral approaches for THA are associated with lower dislocation risk without higher revision risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(11): 3401–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley R A, Charubhumi V, Hutzler L H, Paoli A R, Bosco J A. Joint replacement volume positively correlates with improved hospital performance on Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services quality metrics. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32(5): 1409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderman P, Malchau H, Herberts P, Johnell O. Are the findings in the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register valid? A comparison between the Swedish National Total Hip Arthroplasty Register, the National Discharge Register, and the National Death Register. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15(7): 884–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.