Abstract

Background

Neisseria gonorrhoeae have acquired resistance to many antimicrobials, including third generation cephalosporins and azithromycin, which are the current gonococcal combination therapy recommended by the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Objective

To describe antimicrobial susceptibilities for N. gonorrhoeae circulating in Canada between 2012 and 2016.

Methods

Antimicrobial resistance profiles were determined using agar dilution of N. gonorrhoeae isolated in Canada 2012–2016 (n=10,167) following Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. Data were analyzed by applying multidrug-resistant gonococci (MDR-GC) and extensively drug-resistant gonococci (XDR-GC) definitions.

Results

Between 2012 and 2016, the proportion of MDR-GC increased from 6.2% to 8.9% and a total of 19 cases of XDR-GC were identified in Canada (0.1%, 19/18,768). The proportion of isolates with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins declined between 2012 and 2016 from 5.9% to 2.0% while azithromycin resistance increased from 0.8% to 7.2% in the same period.

Conclusion

While XDR-GC are currently rare in Canada, MDR-GC have increased over the last five years. Azithromycin resistance in N. gonorrhoeae is established and spreading in Canada, exceeding the 5% level at which the World Health Organization states an antimicrobial should be reviewed as an appropriate treatment. Continued surveillance of antimicrobial susceptibilities of N. gonorrhoeae is necessary to inform treatment guidelines and mitigate the impact of resistant gonorrhea.

Keywords: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, antimicrobial resistance, laboratory surveillance, N. gonorrhoeae multidrug resistant

Introduction

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection in Canada, the causative organism being Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In 2016, 23,708 cases of gonorrhea were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC); rates had increased 87%, from 34.9 cases/100,000 population in 2012 to 65.4 cases/100,000 population in 2016 (1). In 2016, 82% of the total reported cases of gonorrhea in Canada occurred in the 15–39 year age group and the highest rates among males were found among those aged 20–29 years and among females aged 15–24 years (2). Globally, there are an estimated 78 million cases of gonorrhea infection occurring per year (3). Treatment is complicated, as N. gonorrhoeae have acquired resistance mechanisms to many of the antimicrobials used for treatment over the years (4). This resistance has been documented by surveillance programs that are used to support appropriate treatment recommendations.

A challenge to gonococcal (GC) surveillance programs is that the number of cultures available for antimicrobial susceptibility testing is on the decline due to the shift from the use of bacterial culture to nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for the diagnosis of gonorrhea. This is of concern as N. gonorrhoeae cultures are also required for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Currently almost 80% of gonococcal infections in Canada are now diagnosed using NAAT (5). Some jurisdictions in Canada no longer maintain the capacity to culture this organism and, therefore, antimicrobial susceptibility data in these jurisdictions are not available.

Canadian gonococcal surveillance data from 2012 reported an increase in isolates with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins, prompting an update to the recommendation for gonorrhea treatment in the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections to combination therapy with two antibiotics. In uncomplicated anogenital infections and pharyngeal infections, ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly (IM) plus azithromycin 1 g orally is currently recommended as a first-line treatment (6).

Along with rising antimicrobial resistance rates, there have also been reports of N. gonorrhoeae with high-level resistance and gonococcal treatment failures; all causes for concern. Treatment failures involving cefixime, a potent oral cephalosporin, have been reported internationally (7–12) as well as in Canada (13,14). Most of these cases were successfully treated with ceftriaxone (250 mg IM). In 2009, Japan identified an isolate (H041) that caused a pharyngeal treatment failure with ceftriaxone that showed unusually high minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to ceftriaxone (2 mg/L) and cefixime (8 mg/L); treatment with ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously cleared the infection (15). More pharyngeal treatment failures to ceftriaxone were reported in Sweden (16,17), Slovenia (18) and Australia (19,20), which were then treated successfully with a higher dosage of ceftriaxone (1 g IM), azithromycin (2 g orally) or a combination of ceftriaxone (250 mg IM) and azithromycin (1 g orally). In 2011, France reported the first genital treatment failure to ceftriaxone in Europe (11). In 2014, the first dual antimicrobial therapy treatment failure was reported in the United Kingdom (UK) (ceftriaxone 500 mg plus azithromycin 1 g) and was successfully treated with ceftriaxone (1 g IM) plus azithromycin (2 g oral) (21). Since 2013, cases of ceftriaxone resistance have been identified and characterized in a number of countries, including Canada, Japan and Australia, which were successfully treated with azithromycin (22,23). The UK and Australia have also recently reported treatment failure cases due to high-level ceftriaxone resistance (MIC=0.5 mg/L) and high-level azithromycin resistance (MIC greater than or equal to 256 mg/L). The UK case was successfully treated with intravenous ertapenem (24).

Rising azithromycin resistance rates have also been reported in Canada (5) and internationally (25), which is of concern as azithromycin is part of the recommended combination therapy. Along with increasing moderate-level azithromycin resistance, there have been reports of high-level azithromycin resistance (MIC greater than or equal to 256 mg/L) that were associated with a large-scale outbreak in the UK (26). Although isolates with this high azithromycin MIC have been identified in Canada, a total of seven were identified between 2009 and 2016 (5); these cases appear to be sporadic occurrences in Canada and have not spread.

In 2009 (27), definitions were established for multidrug-resistant gonococci (MDR-GC) and extensively drug-resistant gonococci (XDR-GC), which we have recently updated, taking into account the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections and the antimicrobials being tested in our routine laboratory surveillance (Text box 1).

Text box 1: Definitions of multidrug-resistant gonococci (MDR-GC) and extensively drug-resistant gonococci (XDR-GC).

MDR-GC – decreased susceptibility/resistance to one currently recommended therapy (cephalosporin OR azithromycin) PLUS resistance to at least two other antimicrobials (penicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin)

XDR-GC – decreased susceptibility/resistance to two currently recommended therapies (cephalosporin AND azithromycin) PLUS resistance to at least two other antimicrobials (penicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin)

PHAC’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML), in collaboration with the provincial laboratories, has been monitoring the antimicrobial susceptibilities of N. gonorrhoeae since 1985. In this report, we present national-level trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities of N. gonorrhoeae collected from 2012 to 2016, applying the updated MDR-GC and XDR-GC definitions.

Methods

Between 2012 and 2016, N. gonorrhoeae cultures were submitted to the NML by provincial laboratories when they identified a resistant (R) isolate or by laboratories that did not conduct antimicrobial susceptibility testing (Table 1). Information regarding the isolates submitted to NML included sex and age of the patient, province/territory where infection was diagnosed, as well as the site of infection. Annually, each province/territory informs the NML of the total number of cultures collected and tested, either in their province/territory or at the NML (Table 1). These totals are used as the denominators in determining the proportions of antimicrobial drug resistance.

Table 1. Neisseria gonorrhoeae cultures collected by provinces and territories and sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML), 2012–2016.

| Year | Cultured | BCa | ABa | SKb | MBb | ONa | QCa | NSb | Otherb,c | Total cultures | Total cases reported in Canada | % of total cases tested by cultures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Collected | 372 | 497 | 57 | 49 | 1,218 | 838 | 0 | 5 | 3,036 | 12,561 | 24.20% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 92 | 93 | 57 | 8 | 396 | 383 | 0 | 4 | 1,033 | ||||

| 2013 | Collected | 454 | 514 | 69 | 29 | 1,404 | 716 | 1 | 8 | 3,195 | 13,786 | 23.20% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 170 | 135 | 67 | 7 | 498 | 298 | 1 | 8 | 1,184 | ||||

| 2014 | Collected | 492 | 468 | 91 | 46 | 1,767 | 918 | 15 | 12 | 3,809 | 16,285 | 23.40% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 335 | 323 | 91 | 46 | 849 | 400 | 14 | 12 | 2,070 | ||||

| 2015 | Collected | 602 | 793 | 62 | 48 | 1,673 | 986 | 13 | 13 | 4,190 | 19,845 | 21.10% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 387 | 512 | 65 | 44 | 1,076 | 531 | 13 | 10 | 2,638 | ||||

| 2016 | Collected | 600 | 786 | 86 | 85 | 1,735 | 1,197 | 32 | 17 | 4,538 | 23,708 | 19.10% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 348 | 695 | 85 | 81 | 1,068 | 927 | 31 | 7 | 3,242 | ||||

| Total | Collected | 2,520 | 3,058 | 365 | 257 | 7,797 | 4,655 | 61 | 55 | 18,768 | 86,185 | 21.80% | |

| Sent to NMLd | 1,332 | 1,758 | 365 | 186 | 3,887 | 2,539 | 59 | 41 | 10,167 | ||||

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; MB, Manitoba; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan

a Province performs antimicrobial susceptibility testing and sends only primarily resistant isolates to the NML

b Province does not perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (Manitoba stopped in 2014) and sends all cultures to the NML

c Other includes Northwest Territories, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island. Nunavut and the Yukon did not report or send any N. gonorrhoeae cultures to the NML from 2012 to 2016

d Numbers include only one culture/case

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of N. gonorrhoeae to azithromycin, cefixime, ceftriaxone, erythromycin, penicillin, spectinomycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, ertapenem and gentamicin were determined using agar dilution (28). The MIC interpretative standards used were as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (28) except for erythromycin (R ≥ 2 mg/L) (29), azithromycin (R ≥ 2 mg/L) (30), ceftriaxone (DS ≥ 0.125 mg/L) and cefixime (DS ≥ 0.25 mg/L) (31), ertapenem (NS ≥ 0.063 mg/L) (32) and gentamicin (R ≥ 32 mg/L) (33,34). The N. gonorrhoeae reference cultures ATCC49226, WHOF, WHOG, WHOK, and WHOP/WHOU were used as controls. Statistical analysis was determined by using EpiCalc 2000 version 1.02 (www.brixtonhealth.com/epicalc.html).

A 2 × 2 χ2 test was used to compare proportions of resistance per year to identify significant differences between years (p values calculated with 99% confidence intervals).

Results

From 2012 through 2016, 21.8% (n=18,768) of the 86,185 cases of N. gonorrhoeae infection reported in Canada (1) were diagnosed by culture. Provincial public health laboratories submitted 10,167 isolates to NML for testing (2012, n=1,033; 2013, n=1,184; 2014, n=2,070; 2015, n=2,638; 2016, n=3,242). Sex and age data of patients were available for 10,104 (99.4%) isolates. Of these, 8,649 (85.6%) were from male patients (median age 30 years; range less than 1–83 years) and 1,455 (14.4%) were from female patients (median age 26 years; range less than 1–71 years). Source specimens included urethral (n=4,836), rectal (n=2,100), pharyngeal (n=1,367), cervical (n=625), vaginal (n=249) and other sources (n=209); sources for 781 isolates were not given. The sexual orientation of patients and information on cases of treatment failure were not available.

Multidrug-resistant gonorrhea

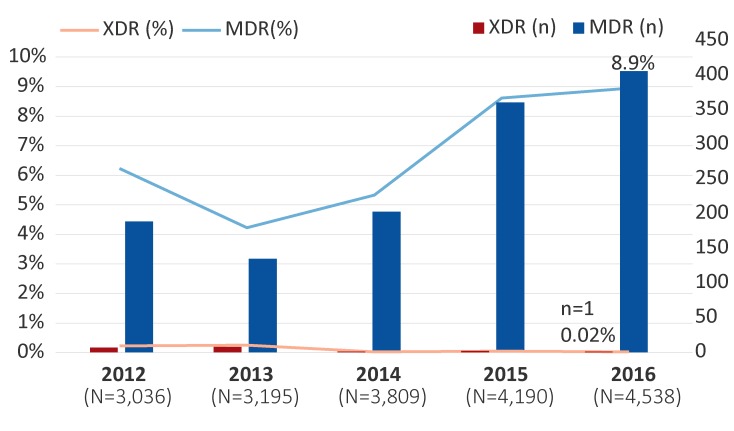

The proportion of MDR-GC increased from 6.2% (n=189/3,036) in 2012 to 8.9% (n=406/4,538) (p<0.001) in 2016. These percentages represent the proportion of isolates with decreased susceptibility to the cephalosporins or resistance to azithromycin, along with resistance to two other antimicrobials (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Canada, 2012–2016a.

Abbreviations: MDR, multidrug-resistant gonococci; n, number; N, total number; XDR, extensively drug-resistant gonococci

a Percentages are based on the total number of isolates tested nationally per year

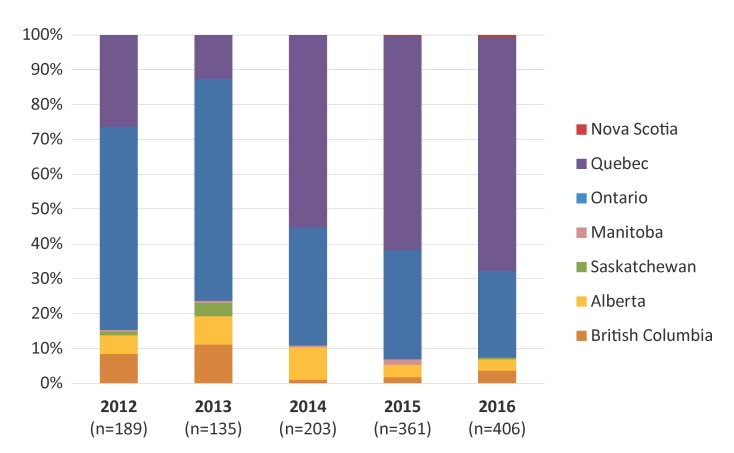

Provincial distribution of MDR-GC identified in Canada is represented in Figure 2, with the highest proportion identified in Quebec (67.0%), followed by Ontario (24.9%) in 2016. British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan also identified cases of MDR-GC in 2016.

Figure 2. Provincial distribution of multidrug-resistant gonococci by year, 2012–2016a.

Abbreviation: n, number

a Percentages are based on the total number of multidrug-resistant gonococci identified each year

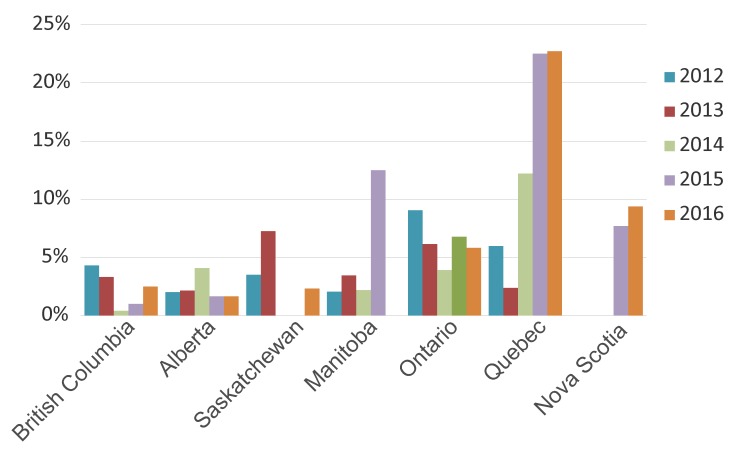

The temporal trends of MDR-GC within each province are displayed in Figure 3, and the provinces with the highest proportions of MDR-GC in 2016 were Quebec (22.7%) followed by Nova Scotia (9.4%) and Ontario (5.8%).

Figure 3. Proportion of multidrug-resistant gonococci in each province from 2012 to 2016a.

a Percentages are based on the total number of cultures in each province

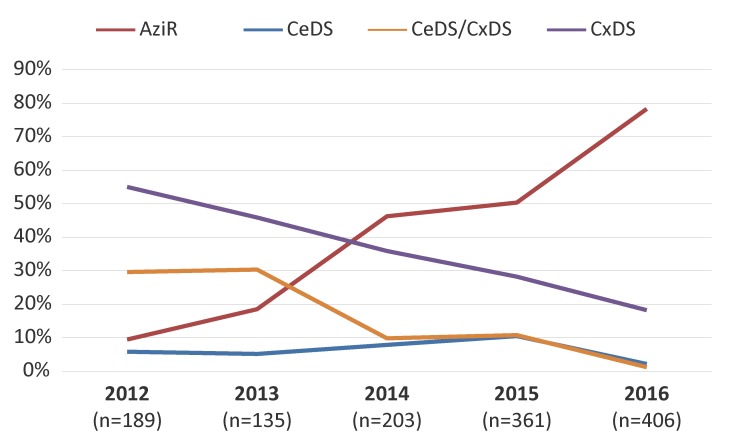

Figure 4 represents the trends of the antimicrobials associated with MDR-GC. The MDR-GC associated with azithromycin resistance increased significantly (p<0.001) from 9.5% in 2012 to 78.3% in 2016. Conversely, MDR-GC associated with decreased susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone declined significantly (p<0.001) from 29.6% in 2012 to 1.2% in 2016.

Figure 4. Trends of antimicrobials associated with multidrug-resistant gonococci, 2012–2016a.

Abbreviations: AziR, azithromycin resistant; CeDS, decreased susceptibility to cefixime; CeDS/CxDS, decreased susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone; CxDS, decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone; n, number

a Percentages based on total number of multidrug-resistant gonococci per year

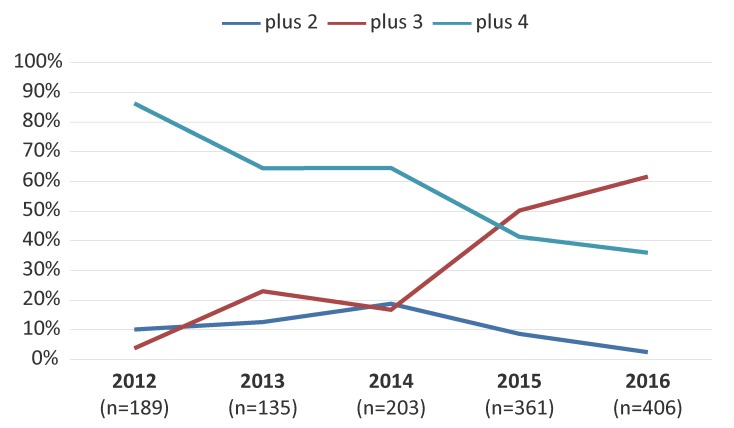

Figure 5 represents the trends of MDR-GC associated with resistance to two, three or four additional antimicrobials. The MDR-GC with resistance to three additional antimicrobials increased significantly (p<0.001) from 3.7% in 2012 to 61.6% in 2016 with ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and tetracycline as the most common co-resistance antimicrobials.

Figure 5. Trends of multidrug-resistant gonococci with resistance to two, three or four additional antimicrobialsa.

Abbreviations: n, number; plus 2, multidrug-resistant gonococci with resistance to two antimicrobials not recommended for therapy; plus 3, multidrug-resistant gonococci with resistance to three antimicrobials not recommended for therapy; plus 4, multidrug-resistant gonococci with resistance to four antimicrobials not recommended for therapy

a Percentages based on total number of multidrug-resistant gonococci per year

Extensively drug-resistant gonococci

From 2012 to 2016, only 19 cases of XDR-GC were identified in Canada (0.1%, n=19/18,768). In 2012, seven XDR-GC isolates with combined decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins and resistance to azithromycin were identified (0.2%, n=7/3,036; Ontario n=6; British Columbia n=1), which increased to eight (0.3%, n=8/3,195; Ontario n=5; British Columbia n=2; Saskatchewan n=1) in 2013. From 2014 to 2016, however, XDR-GC numbers were lower: in 2014, only one was identified (0.03%, n=1/3,809; Quebec); in 2015, two were detected (0.05%, n=2/4,190; Ontario n=1; Quebec n=1); and in 2016, only one XDR-GC was isolated (0.02%, n=1/4,538; British Columbia) (Figure 1).

Trends in resistance patterns

The proportion of N. gonorrhoeae that were identified as susceptible to all antimicrobials tested declined significantly (p<0.001) from 67.5% in 2012 to 35.4% in 2016.

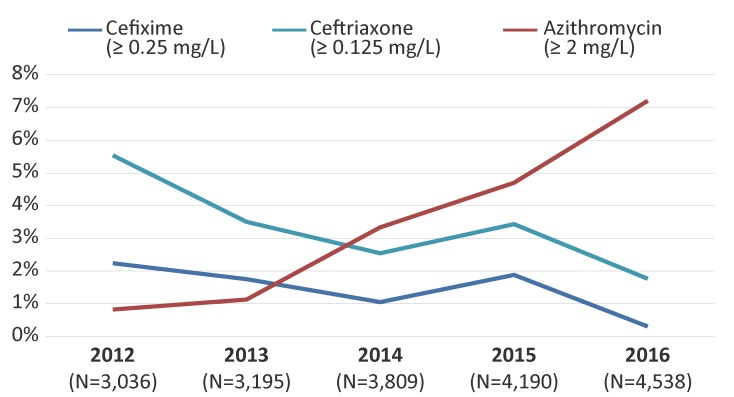

In 2012, 2.2% (n=68/3,036) of isolates had decreased susceptibility to cefixime. This proportion has decreased significantly (p<0.001) to 0.3% (n=14/4,538) in 2016 (Figure 6). Similarly, decreased ceftriaxone susceptibility was 5.5% (n=168/3,036) in 2012 and decreased significantly (p<0.001) to 1.8% (n=80/4,538) by 2016 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Decreased susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone and resistance to azithromycin for Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Canada, 2012–2016a.

Abbreviations: mg/L, milligrams per litre; N, total number; ≥, superior or equal to

a Percentage based on total number of isolates tested nationally

The proportion of azithromycin resistance increased significantly (p<0.001) from 0.8% (n=25/3,036) in 2012 to 7.2% (n=327/4,538) in 2016 (Figure 6). The modal MICs of isolates resistant to azithromycin decreased from 8 mg/L between 2012 and 2014 to 2 mg/L in 2015 and 2016. The range of the MICs was 2 mg/L to 16 mg/L between 2012 and 2015. In 2016, the range was 2 mg/L to 32 mg/L. There were eight isolates with a MIC of 32 mg/L in 2016. Six of these isolates were MDR-GC, the remaining two were only resistant to azithromycin and erythromycin. The above ranges do not include two isolates with a high level of azithromycin resistance (MIC of azithromycin greater than or equal to 256 mg/L), which were identified in 2012 (n=1) and in 2016 (n=1). Both high-level azithromycin resistant isolates were classified as MDR-GC. In 2016, azithromycin resistance was identified in six provinces across Canada with over 90% (n=306/327) identified in Quebec and Ontario (Quebec, 64.5%; Ontario, 28.1%; British Columbia, 2.1%; Alberta, 3.0%; Nova Scotia, 0.9%; and Saskatchewan, 0.3%).

In 2016, 47.1% (n=2,136/4,538) of isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin; 31.7% (n=1,439/4,538) of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin; 17.4% (n=791/4,538) were resistant to penicillin; and 53.3% (n=2,419/4,538) were resistant to tetracycline. Most of these isolates were resistant to more than one antimicrobial. Spectinomycin resistance was not detected in any isolates tested in 2016.

Discussion

The proportion of MDR-GC isolates in Canada increased between 2012 and 2016. While the proportion of N. gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins has decreased, the proportion of isolates resistant to azithromycin has increased, driving the overall increase in MDR-GC. The XDR-GC are rare in Canada and the proportion identified decreased between 2012 and 2016, due to the decline in isolates with decreased susceptibility to the cephalosporins.

In 2013, Canada’s treatment guidelines for uncomplicated gonococcal infection changed from monotherapy with third-generation cephalosporins to combination therapy with ceftriaxone plus azithromycin (6). Once the combination therapy was introduced, a declining trend of decreased cephalosporin susceptibility was identified. The UK, Australia and the United States (US) have reported similar trends. Combination antimicrobial therapy (ceftriaxone 500 mg IM and azithromycin 1 g orally, in a single dose) was recommended for treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections in the UK in 2011 (35). After implementation of the new guidelines, isolates with decreased susceptibility to cefixime declined significantly from 10.8% in 2011 to 5.2% in 2013 (36) and then to 0.6% in 2015 (37). Australia also changed their recommended treatment guidelines (to 500 mg ceftriaxone plus 1 g azithromycin) in 2013 (38). The proportion of isolates with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone declined from 4.4% in 2012 (39) to 1.1% in 2017 (40). The recommended therapy for uncomplicated gonococcal infections in the US was updated to ceftriaxone (250 mg IM) combined with azithromycin (1 g orally) in 2012 (41). In the US, decreased susceptibility to cefixime declined from 0.9% in 2012 to 0.3% in 2016 and decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone remained stable at 0.3% in 2012 and 2016 (42).

While the proportion of decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins has decreased in Canada, the proportion of azithromycin-resistant isolates has increased to 7.2% in 2016 (5), with the majority identified in Quebec and Ontario. Once antimicrobial resistance is established in a region, there is a high risk of these isolates spreading into neighbouring jurisdictions via social networks (43). In 2016, the level of resistance exceeded the 5% level at which the World Health Organization recommends reviewing and modifying national guidelines for treatment of sexually transmitted infections (25). Australia reported similar levels of azithromycin resistance (9.3% in 2017) (44) to Canada; however, the levels in the US (3.6% in 2016) (37) and the UK (4.7% in 2016 [MIC greater or equal to 1 mg/L]) (45) were lower.

The UK and Australia recently reported treatment failures due to high-level XDR-GC with ceftriaxone (MICs=0.5 mg/L) and high-level azithromycin resistance (MIC greater than or equal to 256 mg/L) (24). These strains of XDR-GC threaten the success of the current recommended therapy. With the emerging risk of ceftriaxone resistance and the increasing rate of azithromycin resistance, the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections has added an alternative combination therapy (gentamicin, 240 mg IM plus azithromycin, 2 g oral) to the list of recommended gonococcal therapies (6).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it is a national laboratory-based surveillance system that can identify changing trends in gonococci antimicrobial resistance patterns over time. The limitations of this study include the representativeness of isolates collected in a passive surveillance system, which may be biased towards cultures isolated from specific populations seeking treatment at clinics that provide culture diagnostics. This could lead to considerable missing data concerning affected populations. The epidemiological data are limited and there is a lack of data pertaining to risk factors and demographics. In Canada, cultures were only available for approximately 22% of reported cases for this study period and the remaining cases were diagnosed using NAAT (5); for these cases, antimicrobial susceptibilities were unknown. In addition, the provinces collect cultures according to their own provincial guidelines and perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing using various susceptibility-testing methods.

Next steps

To address the lack of surveillance data in the jurisdictions that have data only from NAAT, the NML developed assays that can be used to predict antimicrobial resistance and sequence type directly from NAAT specimens (46–48). While these assays cannot replace culture-based MIC determinations, they can aid in surveillance by predicting antimicrobial susceptibilities to cephalosporin, ciprofloxacin and azithromycin and, together with molecular typing, can provide an understanding of the types of gonorrhea circulating in a community. This work is not routinely performed but is reserved for remote regions where bacterial culturing is not possible.

To address some of the limitations associated with the national passive laboratory surveillance program, PHAC launched the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistant Gonorrhea in 2013 (49). Laboratory data, such as antimicrobial susceptibility data and sequence typing, are linked to enhanced epidemiological data, which includes demographic and clinical information, risk behaviours, infection site and prescribed treatment information (49). This enhanced laboratory-epidemiological linked surveillance program is currently being conducted in several provinces with plans to expand to other jurisdictions. These data will improve the understanding of antimicrobial-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in Canada and provide better evidence to inform the development of treatment guidelines and public health interventions.

Conclusion

Although rates of MDR-GC increased between 2012 and 2016, XDR-GC in Canada is currently rare. The data presented in this report support efforts to limit the spread of antimicrobial-resistant N. gonorrhoeae and prevent the emergence of XDR-GC. In some parts of Canada, azithromycin-resistant GC have exceeded the 5% level at which the World Health Organization recommends reviewing and modifying treatments. Continued surveillance of gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibilities is vital to inform treatment guidelines and mitigate the spread of MDR-GC and XDR-GC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gary Liu and Norman Barairo for technical support.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. Reported cases from 1991 to 2016 in Canada - Notifiable diseases on-line. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2017. http://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/charts?c=yl

- 2.Bodie M, Gale-Rowe M, Alexandre S, Auguste U, Tomas K, Martin I. There’s no time like the present: prevention and control of the spread of antimicrobial resistant Gonorrhea. Can Commun Dis Rep 2019;45(2/3):54–62. 10.14745/ccdr.v45i23a02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015. Dec;10(12):e0143304. . 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hook EW 3rd, Kirkcaldy RD. A brief history of evolving diagnostics and therapy for gonorrhea: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Sep;67(8):1294–9. . 10.1093/cid/ciy271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada. National Surveillance of Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Canada - Annual Summary 2016. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/national-surveillance-antimicrobial-susceptibilities-neisseria-gonorrhoeae-annual-summary-2016.html

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections – Management and treatment of specific infections - Gonococcal Infections. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2013 (modified Sept 2017). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines/sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines-sexually-transmitted-infections-34.html

- 7.Unemo M, Golparian D, Syversen G, Vestrheim DF, Moi H. Two cases of verified clinical failures using internationally recommended first-line cefixime for gonorrhoea treatment, Norway, 2010. Euro Surveill 2010. Nov;15(47):19721. . 10.2807/ese.15.47.19721-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ison CA, Hussey J, Sankar KN, Evans J, Alexander S. Gonorrhoea treatment failures to cefixime and azithromycin in England, 2010. Euro Surveill 2011. Apr;16(14):19833. www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.16.14.19833-en [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsyth S, Penney P, Rooney G. Cefixime-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the UK: a time to reflect on practice and recommendations. Int J STD AIDS 2011. May;22(5):296–7. . 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unemo M, Golparian D, Stary A, Eigentler A. First Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with resistance to cefixime causing gonorrhoea treatment failure in Austria, 2011. Euro Surveill 2011. Oct;16(43):19998. www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012. Mar;56(3):1273–80. . 10.1128/AAC.05760-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis DA, Sriruttan C, Müller EE, Golparian D, Gumede L, Fick D, de Wet J, Maseko V, Coetzee J, Unemo M. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the first two cases of extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in South Africa and association with cefixime treatment failure. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013. Jun;68(6):1267–70. . 10.1093/jac/dkt034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen VG, Mitterni L, Seah C, Rebbapragada A, Martin IE, Lee C, Siebert H, Towns L, Melano RG, Low DE. Neisseria gonorrhoeae treatment failure and susceptibility to cefixime in Toronto, Canada. JAMA 2013. Jan;309(2):163–70. . 10.1001/jama.2012.176575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh AE, Gratrix J, Martin I, Friedman DS, Hoang L, Lester R, Metz G, Ogilvie G, Read R, Wong T. Gonorrhea treatment failures with oral and injectable expanded spectrum cephalosporin monotherapy vs dual therapy at 4 Canadian sexually transmitted infection clinics, 2010-2013. Sex Transm Dis 2015. Jun;42(6):331–6. . 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohnishi M, Saika T, Hoshina S, Iwasaku K, Nakayama S, Watanabe H, Kitawaki J. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 2011. Jan;17(1):148–9. . 10.3201/eid1701.100397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unemo M, Golparian D, Hestner A. Ceftriaxone treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea verified by international recommendations, Sweden, July 2010. Euro Surveill 2011. Feb;16(6):19792. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.16.06.19792-en [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golparian D, Ohlsson A, Janson H, Lidbrink P, Richtner T, Ekelund O, Fredlund H, Unemo M. Four treatment failures of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with ceftriaxone (500 mg) or cefotaxime (500 mg), Sweden, 2013 and 2014. Euro Surveill 2014. Jul;19(30):20862. . 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.30.20862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unemo M, Golparian D, Potočnik M, Jeverica S. Treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with internationally recommended first-line ceftriaxone verified in Slovenia, September 2011. Euro Surveill 2012. Jun;17(25):20200. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.17.25.20200-en [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Y Chen M, Stevens K, Tideman R, Zaia A, Tomita T, Fairley CK, Lahra M, Whiley D, Hogg G. Failure of 500 mg of ceftriaxone to eradicate pharyngeal gonorrhoea, Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013. Jun;68(6):1445–7. . 10.1093/jac/dkt017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read PJ, Limnios EA, McNulty A, Whiley D, Lahra MM. One confirmed and one suspected case of pharyngeal gonorrhoea treatment failure following 500mg ceftriaxone in Sydney, Australia. Sex Health 2013. Nov;10(5):460–2. . 10.1071/SH13077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fifer H, Natarajan U, Jones L, Alexander S, Hughes G, Golparian D, Unemo M. Failure of dual antimicrobial therapy in treatment of gonorrhea. N Engl J Med 2016. Jun;374(25):2504–6. . 10.1056/NEJMc1512757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefebvre B, Martin I, Demczuk W, Deshaies L, Michaud S, Labbé AC, Beaudoin MC, Longtin J. Ceftriaxone-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Canada, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2018. Feb;24(2):381–3. . 10.3201/eid2402.171756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahra MM, Martin I, Demczuk W, Jennison AV, Lee KI, Nakayama SI, Lefebvre B, Longtin J, Ward A, Mulvey MR, Wi T, Ohnishi M, Whiley D. Cooperative recognition of internationally disseminated ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain. Emerg Infect Dis 2018. Apr;24(4):735–40. . 10.3201/eid2404.171873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stockholm. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United Kingdom and Australia - 7 May 2018. Stockholm (SE): ECDC; 2018. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/RRA-Gonorrhoea%2C%20Antimicrobial%20resistance-United%20Kingdom%2C%20Australia.pdf

- 25.World Health Organization (WHO). Report on Global Sexually Transmitted Infection Surveillance, 2015. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2016. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/stis-surveillance-2015/en/

- 26.Fifer H, Cole M, Hughes G, Padfield S, Smolarchuk C, Woodford N, Wensley A, Mustafa N, Schaefer U, Myers R, Templeton K, Shepherd J, Underwood A. Sustained transmission of high-level azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018. May;18(5):573–81. . 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, Unemo M. Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2009. Sep;7(7):821–34. . 10.1586/eri.09.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI - M100-S27. Wayne (PA): Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. https://standards.globalspec.com/std/10066309/m100-s27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Ehret JM, Nims LJ, Judson FN. A clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with in vitro resistance to erythromycin and decreased susceptibility to azithromycin. Sex Transm Dis 1996. Jul-Aug;23(4):270–2. . 10.1097/00007435-199607000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2007 supplement, gonococcal isolate surveillance project (GISP) annual report 2007. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/sexually-transmitted-disease-surveillance-2007-supplement-gonococcal-isolate

- 31.World Health Organization. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae Geneva (CH): WHO; 2012. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241503501/en/

- 32.Unemo M, Fasth O, Fredlund H, Limnios A, Tapsall J. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the 2008 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strain panel intended for global quality assurance and quality control of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance surveillance for public health purposes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009. Jun;63(6):1142–51. . 10.1093/jac/dkp098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown LB, Krysiak R, Kamanga G, Mapanje C, Kanyamula H, Banda B, Mhango C, Hoffman M, Kamwendo D, Hobbs M, Hosseinipour MC, Martinson F, Cohen MS, Hoffman IF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in Lilongwe, Malawi, 2007. Sex Transm Dis 2010. Mar;37(3):169–72. . 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf575c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daly CC, Hoffman I, Hobbs M, Maida M, Zimba D, Davis R, Mughogho G, Cohen MS. Development of an antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance system for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Malawi: comparison of methods. J Clin Microbiol 1997. Nov;35(11):2985–8. https://jcm.asm.org/content/35/11/2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bignell C, Fitzgerald M; Guideline Development Group. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV UK. UK national guideline for the management of gonorrhoea in adults, 2011. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22(10):541–7. . 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Public Health England. GRASP 2013 Report; the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (England and Wales). London, (UK): PHE; 2014. Report No: 2014442. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/368477/GRASP_Report_2013.pdf

- 37.Public Health England. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae key findings from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP). London (UK): PHE; 2016. www.researchgate.net/publication/312616605_Surveillance_of_antimicrobial_resistance_in_Neisseria_gonorrhoeae_Key_findings_from_the_Gonococcal_Resistance_to_Antimicrobials_Surveillance_Programme_GRASP_Antimicrobial_resistance_in_Neisseria_gonor

- 38.Government of Western Australia, Department of Health. New treatment guidelines for Neisseria gonorrhoeae Disease Watch. 2013;17(3). www.health.wa.gov.au/diseasewatch/vol17_issue3/gonorrhoeae-treatment.cfm

- 39.Lahra MM; Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme. Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme annual report, 2013. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2015. Mar;39(1):E137–45. www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/cda-cdi3901-pdf-cnt.htm/$FILE/cdi3901h.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lahra MM, Enriquez RP; National Neisseria Network. Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme annual report, 2015. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2017. Mar;41(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC’s Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012. Aug;61(31):590–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2016: Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) Supplement & Profiles. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/gisp2016/docs/gisp_2016_supplement_final_2018.pdf

- 43.Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014. Jul;27(3):587–613. . 10.1128/CMR.00010-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lahra MM, Enriquez R, George CR; National Neisseria Network, Australia. Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme Annual Report, 2017. Government of Australia, Health Department: 2017. www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/BE39C1C702DBA06FCA25829700839388/$File/wAnnual-Report-2017.docx

- 45.Public Health England. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England and Wales: Key Finding from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP). Data to June 2017. London, (UK): PHE; 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/651636/GRASP_Report_2017.pdf

- 46.Peterson SW, Martin I, Demczuk W, Bharat A, Hoang L, Wylie J, Allen V, Lefebvre B, Tyrrell G, Horsman G, Haldane D, Garceau R, Wong T, Mulvey MR. Molecular Assay for Detection of Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates from Cultures and Clinical Nucleic Acid Amplification Test Specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2015. Nov;53(11):3606–8. . 10.1128/JCM.01632-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson SW, Martin I, Demczuk W, Bharat A, Hoang L, Wylie J, Allen V, Lefebvre B, Tyrrell G, Horsman G, Haldane D, Garceau R, Wong T, Mulvey MR. Molecular Assay for Detection of Genetic Markers Associated with Decreased Susceptibility to Cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol 2015. Jul;53(7):2042–8. . 10.1128/JCM.00493-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson SW, Martin I, Demczuk W, Hoang L, Wylie J, Lefebvre B, Labbé AC, Naidu P, Haldane D, Mulvey MR. A Comparison of Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays for the Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Markers and Sequence Typing From Clinical Nucleic Acid Amplification Test Samples and Matched Neisseria gonorrhoeae Culture. Sex Transm Dis 2018. Feb;45(2):92–5. . 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea – Results from the 2014 Pilot. Ottawa (ON): PHAC; 2018. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/gonorrhea-2014-pilot-surveillance-antimicrobial-resistant.html