Abstract

Background

Herpes simplex labialis (HSL), also known as cold sores, is a common disease of the lips caused by the herpes simplex virus, which is found throughout the world. It presents as a painful vesicular eruption, forming unsightly crusts, which cause cosmetic disfigurement and psychosocial distress. There is no cure available, and it recurs periodically.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions for the prevention of HSL in people of all ages.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to 19 May 2015: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, the Oral Health Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library (Issue 4, 2015), MEDLINE (from 1946), EMBASE (from 1974), LILACS (from 1982), the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database, Airiti Library, and 5 trial registers. To identify further references to relevant randomised controlled trials, we scanned the bibliographies of included studies and published reviews, and we also contacted the original researchers of our included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions for preventing HSL in immunocompetent people.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected trials, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias. A third author was available for resolving differences of opinion.

Main results

This review included 32 RCTs, with a total of 2640 immunocompetent participants, covering 19 treatments. The quality of the body of evidence was low to moderate for most outcomes, but was very low for a few outcomes. Our primary outcomes were 'Incidence of HSL' and 'Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention'.

The evidence for short‐term (≤ 1 month) use of oral aciclovir in preventing recurrent HSL was inconsistent across the doses used in the studies: 2 RCTs showed low quality evidence for a reduced recurrence of HSL with aciclovir 400 mg twice daily (risk ratio (RR) 0.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13 to 0.51; n = 177), while 1 RCT testing aciclovir 800 mg twice daily and 2 RCTs testing 200 mg 5 times daily found no similar preventive effects (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.87; n = 237; moderate quality evidence and RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.07; n = 66; low quality evidence, respectively). The direction of intervention effect was unrelated to the risk of bias. The evidence from 1 RCT for the effect of short‐term use of valaciclovir in reducing recurrence of HSL by clinical evaluation was uncertain (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.28; n = 125; moderate quality evidence), as was the evidence from 1 RCT testing short‐term use of famciclovir.

Long‐term (> 1 month) use of oral antiviral agents reduced the recurrence of HSL. There was low quality evidence from 1 RCT that long‐term use of oral aciclovir reduced clinical recurrences (1.80 versus 0.85 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period, P = 0.009) and virological recurrence (1.40 versus 0.40 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period, P = 0.003). One RCT found long‐term use of valaciclovir effective in reducing the incidence of HSL (with a decrease of 0.09 episodes per participant per month; n = 95). One RCT found that a long‐term suppressive regimen of valaciclovir had a lower incidence of HSL than an episodic regimen of valciclovir (difference in means (MD) ‐0.10 episodes per participant per month, 95% CI ‐0.16 to ‐0.05; n = 120).

These trials found no increase in adverse events associated with the use of oral antiviral agents (moderate quality evidence).

There was no evidence to show that short‐term use of topical antiviral agents prevented recurrent HSL. There was moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs that topical aciclovir 5% cream probably has little effect on preventing recurrence of HSL (pooled RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.72; n = 271). There was moderate quality evidence from a single RCT that topical foscarnet 3% cream has little effect in preventing HSL (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.40; n = 295).

The efficacy of long‐term use of topical aciclovir cream was uncertain. One RCT found significantly fewer research‐diagnosed recurrences of HSL when on aciclovir cream treatment than on placebo (P < 0.05), but found no significant differences in the mean number of participant‐reported recurrences between the 2 groups (P ≥ 0.05). One RCT found no preventive effect of topical application of 1,5‐pentanediol gel for 26 weeks (P > 0.05). Another RCT found that the group who used 2‐hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclo dextrin 20% gel for 6 months had significantly more recurrences than the placebo group (P = 0.003).

These studies found no increase in adverse events related to the use of topical antiviral agents.

Two RCTs found that the application of sunscreen significantly prevented recurrent HSL induced by experimental ultraviolet light (pooled RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.33; n = 111), but another RCT found that sunscreen did not prevent HSL induced by sunlight (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.25 to 5.06; n = 51). These RCTs did not report adverse events.

There were very few data suggesting that thymopentin, low‐level laser therapy, and hypnotherapy are effective in preventing recurrent HSL, with one to two RCTs for each intervention. We failed to find any evidence of efficacy for lysine, LongoVital® supplementation, gamma globulin, herpes simplex virus (HSV) type I subunit vaccine, and yellow fever vaccine in preventing HSL. There were no consistent data supporting the efficacy of levamisole and interferon, which were also associated with an increased risk of adverse effects such as fever.

Authors' conclusions

The current evidence demonstrates that long‐term use of oral antiviral agents can prevent HSL, but the clinical benefit is small. We did not find evidence of an increased risk of adverse events. On the other hand, the evidence on topical antiviral agents and other interventions either showed no efficacy or could not confirm their efficacy in preventing HSL.

Plain language summary

Measures for preventing cold sores

Review question

What measures are effective in preventing recurrence of cold sores?

Background

A cold sore is an irritating recurrent viral infection with no proven cure. It gives rise to painful vesicles on the lips that form unsightly crusts, causing an unpleasant look and mental distress. We aimed to examine the effects of available measures for preventing recurrence of cold sores in people with normal immunity.

Study characteristics

We examined the research published up to 19 May 2015. We wanted to include studies only if receiving one preventative measure or another was decided by chance. This research method, termed randomised controlled trial (RCT), is the best way to test that a preventive effect is caused by the measure being tested. We found 32 RCTs that included 2640 people and examined 19 preventative measures. The drug manufacturer funded a total of 18 out of 32 studies, non‐profit organisations funded 4, and we do not know how the other 10 were funded.

Key results

Long‐term use of antiviral drugs taken by mouth prevented cold sores, though with a very small decrease of 0.09 episodes per person per month. The preventative effect of long‐term use of aciclovir cream applied to the lips was uncertain. Long‐term use of 1,5‐pentanediol gel and 2‐hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclo dextrin 20% gel applied to the lips did not prevent cold sores.

Short‐term use of either antiviral drugs or creams did not prevent cold sores. Neither short‐term nor long‐term use of these antiviral drugs or creams appeared to cause side‐effects.

The preventative effects of sunscreen were uncertain. Application of sunscreen prevented cold sores induced by experimental ultraviolet light, but did not prevent cold sores induced by sunlight.

We found very little evidence about the preventative effects of thymopentin, low‐energy laser, and hypnotherapy for cold sores. The available evidence found no preventative effects of lysine, LongoVital® supplementation, gamma globulin, herpes virus vaccine, and yellow fever vaccine. There were no consistent data to confirm that levamisole and interferon do prevent cold sores.

These studies found no increase in adverse events related to the use of topical antiviral agents.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was low to moderate for most outcomes, but was very low for some outcomes.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

A virus that resides in the skin of the lips causes herpes simplex labialis (HSL) (Higgins 1993). Its manifestation on the skin is also known as a 'cold sore' or 'fever blister'. The initial infection with the virus, which is called herpes simplex virus (HSV), is by direct contact between the mucous membranes or abraded skin of the lips or mouth and the saliva or other secretions of a person with active primary or recurrent infection (Higgins 1993). Primary infection with HSV typically occurs in early childhood, often with no symptoms, but primary HSV infection may also present as herpetic gingivostomatitis, which is characterised by oral and perioral vesicles (tiny blisters) and ulcers (Higgins 1993). It has been reported that when clinical disease is not present, the virus spreads through respiratory droplets or through interaction with the mucocutaneous releases of an asymptomatic person shedding the virus (Fatahzadeh 2007). Following the primary infection, the virus resides in the sensory ganglia (nerve endings) in a latent form (Higgins 1993). After reactivation, HSV migrates from these sensory ganglia to the outer layer of the skin of the lips or mouth to cause recurrent HSL (Fatahzadeh 2007). Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV‐1) causes recurrent HSL. Although herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV‐2) may occasionally cause primary oral infection, it rarely causes recurrent HSL (Fatahzadeh 2007).

Herpes simplex labialis affects the lips, with the outer third of the lower lip being most frequently affected (Marques 2003). In up to 60% of affected people, HSL is preceded by warning signs, which are known as 'prodromal symptoms'; these are feelings of pain, burning, itching, or tingling at the site of subsequent vesicle development. Headache may also occur in the prodromal stage (Joseph 1985). Within 24 hours of the prodrome, multiple grouped vesicles appear and then weep until they finally form crusts (Fatahzadeh 2007). Such crusts can often bleed quite easily, forming unsightly blackish crusts due to dried blood, which can bleed again when the skin is stretched, e.g., when smiling (Fatahzadeh 2007). These usually heal without scarring within 5 to 15 days (Marques 2003). Herpes simplex labialis may cause pain, discomfort, inconvenience, and some amount of psychological and social distress as a result of cosmetic disfigurement (Fatahzadeh 2007).

Herpes simplex labialis occurs worldwide and is a very common disease (Higgins 1993). The lifetime prevalence of recurrent herpes labialis is 20% to 52.5% (Celik 2013; Higgins 1993). It has been estimated that there are 98 million cases of HSL each year in the US alone (Higgins 1993). Most people with recurrent HSL have fewer than 2 episodes per year, but 5% to 10% of affected people have a minimum of 6 recurrences per annum (Celik 2013; Rooney 1993). Recurrences of HSL seem to be precipitated by a number of factors, including ultraviolet light (UVL); illness; stress; premenstrual tension; severe drug eruptions; and surgical procedures, such as dental surgery, neural surgery, and dermabrasion (a cosmetic procedure used to smooth scars) (Celik 2013; Higgins 1993; Shiohara 2013). People with atopic dermatitis who carry filaggrin mutations are prone to recurrent HSL, which may be attributed to their deficient antiviral immune response (Leung 2014; Rystedt 1986).

Description of the intervention

To date, there has been no proven way of eradicating HSV from the body completely. A number of interventions have been proposed for the prevention of recurrent HSL, including oral antivirals, topical antivirals, and sunscreens (Worrall 2009).

Antiviral agents, including aciclovir, famciclovir, penciclovir, and valaciclovir, inhibit DNA polymerase and viral replications. Before converting to the active antiviral triphosphate form, these drugs need to be phosphorylated by enzymes, such as viral thymidine kinase (TK) or host cellular kinases. Compared with aciclovir, famciclovir and valaciclovir have greater bioavailability and need less frequent dosing. Foscarnet inhibits viral DNA polymerase independent of phosphorylation and is thus used in aciclovir‐resistant HSV infections (Fatahzadeh 2007).

The active ingredients of sunscreens are generally classified into inorganic and organic UVL filters. Inorganic filters, such as titanium oxide, reflect or scatter UVL, while organic filters absorb UVL and convert the energy into heat. The most frequently‐used efficacy index of sunscreen in preventing sunburns is the sun protection factor (SPF), which is measured after application of 2 mg/cm² of product (Kullavanijaya 2005).

How the intervention might work

Long‐term prophylactic administration of oral antivirals (e.g., aciclovir, famciclovir, and valaciclovir) is expected to prevent reactivation of HSV (Worrall 2009). However, continuous daily intake of antivirals is not only costly but also requires the person to adhere to such a programme consistently (Fatahzadeh 2007). Therefore, it is important to design an optimal regimen, balancing known effectiveness of any preventative intervention with the inconvenience and possible side‐effects of continuous medication.

When topical aciclovir cream is used as a treatment for HSL, the frequency of application is five times daily (four hours apart except for sleep) (GSK 2008). However, the efficacy and frequency of application when used as a preventative intervention is unclear.

Based on the fact that ultraviolet light induces the recurrence of HSL (Higgins 1993), sunscreens, theoretically, can prevent recurrence of HSL. However, commercially available sunscreens vary greatly in their active ingredients and the effectiveness of their photoprotection. The effectiveness of photoprotection also depends on the appropriate application of sunscreens; frequency of re‐application after sweating or water sports (Kullavanijaya 2005); and in the case of lips, eating or drinking (Rooney 1991). In actual use, most people apply less than the amounts used in testing SPF, which compromises the efficacy of the sunscreen (Kullavanijaya 2005). Photoprotective lipscreens often contain less UVL‐absorbing ingredients than skin sunscreens (Wahie 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

There has been a Cochrane review on the effects of systemic aciclovir for primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (Nasser 2008) and another on the interventions for the prevention and treatment of HSV in people being treated for cancer (Glenny 2009). However, a systematic review on interventions for preventing HSL in those who are immunocompetent is lacking. We aimed to conduct such a review in order to find out the best evidence on the effects of those interventions currently available for the prevention of recurrent HSL.

The plans for this review were published as a protocol 'Interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips)' (Chi 2012).

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions for the prevention of HSL in people of all ages.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of systemic, topical, and physical interventions for the prevention of herpes simplex labialis (HSL).

Types of participants

Anyone who was immunocompetent and had been initially diagnosed with recurrent HSL by a healthcare professional or trained researcher.

Types of interventions

Any systemic, topical, or physical intervention used for the prevention of HSL. The interventions could be either a single intervention or a combination of interventions. When there were different lengths of use of the intervention, we regarded those of ≤ 1 month as short‐term use and those of > 1 month as long‐term use. The controls might be a placebo, no intervention, or another active intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of HSL during use of the preventative intervention. We accepted both researcher‐diagnosed and participant‐reported recurrences.

Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Duration of attack of recurrent HSL during use of the preventative intervention.

Severity (lesion area, stage, pain) of attack of recurrent HSL during use of the preventative intervention.

Viral load in saliva.

Rate of adherence to the regimen of the preventative intervention.

Incidence of HSL after use of the preventative intervention. We accepted both researcher‐diagnosed and participant‐reported recurrences.

Duration of attack of recurrent HSL after use of the preventative intervention.

Severity (lesion area, stage, pain) of attack of recurrent HSL after use of the preventative intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases up to 19 May 2015:

the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issue 4, 2015) using the strategy in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 3;

EMBASE via Ovid (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 4; and

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 5.

We searched the Cochrane Oral Health Group Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1 up to 19 May 2015.

On 22 May 2015, we searched the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CKNI) database (from 1994) using the strategy in Appendix 6 and Airiti Library (publications and theses from Taiwan, from 1991) using the strategy in Appendix 7.

Trials registers

We searched the following trials databases on 25 May 2015 using the strategy in Appendix 8.

The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

The Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

The EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

We searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com) on 13 June 2014, but this was closed and under review when we updated our search on 25 May 2015.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We scanned the bibliographies of the included studies and published reviews for further references to relevant trials.

Unpublished literature

We tried to identify further unpublished trials through correspondence with the original researchers of the included studies.

Adverse effects

We did not run separate searches for adverse effects of the target interventions. However, we did extract relevant data from the included trials that we identified.

Data collection and analysis

Some parts of this section uses text that was originally published in another Cochrane review (Chi 2011). We included 'Summary of findings' tables where we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the quality of the evidence for the primary outcomes for the treatment comparisons.

Selection of studies

Two authors (CC and SW) independently checked titles and abstracts identified from the searches. The authors were not blinded to the names of the original researchers, journals, or institutions. If it was clear from the abstract that the study did not refer to a RCT on interventions for prevention of HSL, we excluded it. The same two authors independently assessed the full text version of each remaining study to determine whether it met the predefined selection criteria. We resolved any disagreement by discussion with referral to a third author (FW), if necessary. We listed the studies that we could only exclude after reading the full text and reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (CC and SW) independently extracted the data using a specialised data extraction form. We resolved discrepancies by discussion with a third author (FW). One author (CC) entered the data into Review Manager (RevMan) (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated the following components since there is some evidence that these are associated with biased estimates of intervention effect (Higgins 2011):

random sequence generation ‐ adequacy of the method of random sequence generation to produce comparable groups in every aspect except for the intervention;

allocation concealment ‐ adequacy of the method used to conceal the allocation sequence to prevent anyone foreseeing the allocation sequence in advance of, or during, enrolment;

blinding of participants and personnel ‐ adequacy of blinding study participants and researchers from knowledge of the allocated interventions;

blinding of outcome assessment ‐ adequacy of blinding outcome assessors from knowledge of the allocated interventions;

incomplete outcome data ‐ the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis, whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusions where reported, and any re‐inclusions in our analyses;

selective reporting ‐ whether all prespecified outcomes were reported when the trial protocol was available; and

other sources of bias ‐ any other important concerns about bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed the results as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and where appropriate as number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) with 95% CI and the baseline risk to which it applies. For continuous outcomes, we expressed the results as difference in means (MD) with 95% CI or where different outcome scales were pooled as standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CI. For time‐to‐event outcomes, we expressed the results as hazard ratios (HRs). If Kaplan‐Meier curves were presented, we would have extracted the data from the graphs and calculated HRs according to the methods given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). However, time‐to‐event outcomes were treated as continuous data in a few included trials. We therefore could only present the original data reported.

With regard to our primary outcome 'Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention', we measured this by assessing the proportion of participants who experienced adverse events.

With regard to our secondary outcome 'Rate of adherence to the regimen of the preventative intervention', we measured this by assessing either the proportion of participants who adhered to the interventions or the mean proportion of interventions participants received.

Unit of analysis issues

All randomised participants in the control and intervention groups were the unit of analysis. We did not pool the following types of studies with studies of other designs.

Cluster‐randomised trials

For cluster‐randomised trials, we would have used appropriate techniques described in section 16.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Cross‐over trials

For cross‐over trials, we used appropriate techniques described in section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where there were multiple intervention groups within a trial, we made pair‐wise comparisons of an intervention versus no intervention, placebo, or another active intervention.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original researchers of studies less than 15 years old for missing data (Table 21). When the missing data were not available, we initially assumed those data were missing at random. If the missing data were caused by participants' dropout, we conducted intention‐to‐treat analyses. For dichotomous outcomes, we would have regarded participants with missing outcome data as treatment failures and included them in the analyses. For continuous outcomes, we would have carried forward the last recorded value for participants with missing outcome data. Where high levels of missing data were seen within the analyses, we would have conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results from the approach described above by comparing the results with those that exclude the missing data from the analyses. However, we failed to conduct the planned analyses because of lacking adequate data, for example, the respective number of randomised participants and those who were lost to follow up in each group.

1. Trialists contacted for missing or unpublished data.

| Study | Enquiries | Reply |

| Baker 2003 | We sent the following request on 13 February 2015: (1) How did you randomise the participants? (2) Did you do any measures for allocation concealment? (3) Could you please offer the details of how you achieved double blindness? (4) Did you use a person other than the physician to assess the outcomes? |

No reply |

| de Carvalho 2010 | We sent the following request on 23 June 2014: (1) How did you randomise the participants? (2) Did you do any measures for allocation concealment? (3) Did you use a person other than the physician to assess the outcomes? (4) The number of dropouts or withdrawals in this trial (5) Did you assess any outcomes regarding adverse events? If you did, what were the results? |

4 August 2014 (1) Randomisation was down through sortition (2) No (3) No (4) 01 (5) Adverse events were evaluated, but there were no adverse events detected |

| Gilbert 2007 | We sent the following request on 13 February 2015: (1) How did you randomise the participants? (2) Did you do any measures for allocation concealment? |

No reply |

| Pfitzer 2005 | We sent the following request on 23 June 2014: (1) How did you randomise the participants? (2) Did you do any measures for allocation concealment? (3) The number of dropouts or withdrawals in this trial (4) Did you assess any outcomes regarding adverse events? If you did, what were the results? |

No reply |

| Senti 2013 | This trial was identified from searching trial registers (NCT00914745). We sent the following request on 27 December 2013: "Dear Prof Kündig, I am conducting a Cochrane review on interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010095/abstract). I have noticed that you have completed a trial (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00914745) that assessed a topical ointment for prevention of herpes simplex labialis, and was wondering if you would like to share your results with us, thus we could include your trial in our review. Your assistance would be appreciated" |

The trialists provided us with the full published article |

| ISRCTN03397663 | We sent the following request on 27 December 2013: "Dear Dr Cheras, I am conducting a Cochrane review on interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010095/abstract). I have noticed that you completed a trial that used Sheabutter extract BSP110 for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ISRCTN03397663#?close=1). I was wondering if you would like to share your results with us. Thus, we could include your trial in our review. Your assistance would be appreciated" |

No reply |

| NCT01225341 | We sent the following request on 27 December 2013: "Dear Dr Dayan, I am conducting a Cochrane review on interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010095/abstract). I have noticed that you are conducting a trial that uses botulinum toxin A injections for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01225341). I was wondering if you have completed the trial and would like to share your results with us. Thus, we could include your trial in our review. Your assistance would be appreciated" |

No reply |

| NCT01971385 | We sent the following request on 19 January 2014: "Dear Dr Kimball, I am conducting a Cochrane review on interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010095/abstract). I have noticed that you are doing a trial (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01971385) that assessed a topical ointment for prevention of herpes simplex labialis, and was wondering if you would like to share your results with us if you have completed the trial, thus we could include your trial in our review. Your assistance would be greatly appreciated" |

No reply |

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity inherent in the study design, interventions, participants, and outcome measures to determine whether a meta‐analysis was appropriate. The anticipated clinical heterogeneity included various lengths and regimens of the same intervention, presence of atopic dermatitis, and induction by UVL. We also determined the I² statistic to assess the statistical heterogeneity. When there was clinical heterogeneity or the I² statistic was greater than 80%, we did not perform a meta‐analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We would have tested publication bias for primary outcomes by using a funnel plot when at least 10 trials on an intervention were available. However, the limited number of trials for each intervention meant it was impossible to do this test.

Data synthesis

For trials on a particular intervention, we conducted a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model (DerSimonian and Laird model) to calculate a weighted intervention effect across trials when the I² statistic was 80% or less with reasonable clinical homogeneity. We decided clinical homogeneity based on similar participants and intervention regimens. Where it was inappropriate or impossible to perform a meta‐analysis, we summarised the data narratively for each trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We discussed similarities and differences of included RCTs in terms of the study design, interventions, participants, and outcome measures. We would have conducted subgroup analyses of the following if adequate data were available:

participants with atopic dermatitis: we found no data relevant to atopic dermatitis and thus did not conduct a subgroup analysis; and

participants with UVL‐induced HSL: for sunscreen where relevant data were available, we conducted a subgroup analysis on HSL induced by natural and experimental UVL separately.

Sensitivity analysis

We would have performed a sensitivity analysis to examine the intervention effects after excluding those studies with lower methodological quality if appropriate. However, we did not do so because of a very limited number of trials for the same intervention.

Other

We involved a consumer coauthor (FD) throughout the review process to help improve the relevance and readability of the final review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

As shown in Figure 1, our search identified 1387 citations. After removing duplicates, we assessed 1329 citations. We excluded 1252 citations because the title, abstract, or both did not meet our inclusion criteria. We sought the full texts of the remaining 77 citations. We excluded 38 citations, mostly because these were either non‐randomised studies or randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on interventions for treatments of herpes simplex labialis (HSL). Of the remaining 39 citations, we transferred 4 studies to the section 'Ongoing studies' as they were not yet completed. We included the remaining 35 citations, reporting 32 relevant trials, in this review. One included citation reported four trials, of which three met our inclusion criteria (Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b; Spruance 1991c). Five included trials, Miller 2004; Pazin 1979; Pedersen 2001; Russell 1978; Schindl 1999, had two citations.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

This review included 32 trials, with a total of 2640 participants, covering 19 treatments. We describe the details of the included studies in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables.

Design

All of the 32 included studies were RCTs, with 5 being cross‐over RCTs (Gibson 1986; Gilbert 2007; Rooney 1991; Rooney 1993; Thein 1984).

Sample sizes

The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 19 to 310. Seven of the included trials had a small sample size of less than 30 participants (Duteil 1998; Gibson 1986; Møller 1997; Pfitzer 2005; Rooney 1993; Thein 1984).

Setting

The setting was multicentre in 13 trials (Altmeyer 1991; Bernstein 1994; Bernstein 1997; Bolla 1985; Busch 2009; Gibson 1986; Mills 1987; Raborn 1997; Raborn 1998; Rooney 1991; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1991c; Spruance 1999) and single‐centre in 19 trials (Baker 2003; de Carvalho 2010; Duteil 1998; Gilbert 2007; Ho 1984; Miller 2004; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Pedersen 2001; Pfitzer 2005; Redman 1986; Rooney 1993; Russell 1978; Schädelin 1988; Schindl 1999; Senti 2013; Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b; Thein 1984). All of the included trials were conducted either in Europe or North America.

Participants

All of the included trials included adults aged 18 years or older, with 2 trials extending to persons aged 16 years or older, Bolla 1985; Gibson 1986, and 1 trial extending to persons aged at least 12 years (Miller 2004). Two trials, Russell 1978; Thein 1984, did not state the age limit of inclusion criteria but included participants aged seven and eight years, respectively.

Interventions

The included trials assessed the effects of 19 interventions for preventing HSL, including 6 oral treatments (aciclovir (Raborn 1998; Rooney 1993; Schädelin 1988; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b), valaciclovir (Baker 2003; Gilbert 2007; Miller 2004), famciclovir (Spruance 1999), levamisole (Russell 1978), lysine (Thein 1984), and LongoVital® (a vitamin and herbs supplement) (Pedersen 2001)), 5 topical treatments (aciclovir cream (Gibson 1986; Raborn 1997; Spruance 1991c), aciclovir plus 348U87 cream (Bernstein 1994), topical foscarnet 3% (Bernstein 1997), 1,5‐pentanediol (a low‐toxicity molecule with an antiviral activity) gel (Busch 2009), 2‐hydroxypropyl‐β‐cyclo dextrin gel (Senti 2013)), sunscreens (Duteil 1998; Mills 1987; Rooney 1991), 3 immunomodulating treatments given by injection (interferon (Ho 1984; Pazin 1979), intradermal gamma globulin (Redman 1986), and thymopentin (Bolla 1985)), 2 vaccines (herpes simplex virus (HSV) type I subunit vaccine (Altmeyer 1991) and yellow fever vaccination (Møller 1997)), low‐intensity lasers (de Carvalho 2010; Schindl 1999), and hypnotherapy (Pfitzer 2005).

Outcomes

Of the 32 included trials, all reported either the incidence or frequency of HSL during use of the preventative intervention, and 17 trials (53%) reported adverse events. There were 12 and 20 trials reporting the duration and severity of recurrent HSL, respectively. Only one trial, Miller 2004, measured the shedding of HSV in the saliva, and only two trials, Rooney 1993; Spruance 1999, assessed participants' adherence to study medications.

Funding source

Of the included 32 trials, industry supported 18, and non‐profit organisations (such as government or academic institutions) supported 4; the other 10 trials did not report the funding source.

Excluded studies

We excluded 38 citations after examining the full text. We list the reasons for exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Ongoing Studies

We identified 4 ongoing trials that were on a sheabutter extract (BSP110), botulinum toxin A injection, an experimental drug (BTL‐TML‐HSV), and squaric acid dibutylester, respectively (ISRCTN03397663; NCT01225341; NCT01902303; NCT01971385). We contacted the four trialists, but none of them replied. We present the details of these trials in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

We summarise our judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all of the included trials in Figure 2, and we summarise our judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included trial in Figure 3. We present further details in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the 'Characteristics of included studies' section. The risk of bias of the included trials varied from low to high.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

Nine trials used an adequate method of generation of the randomisation sequence (Bernstein 1994; Busch 2009; de Carvalho 2010; Miller 2004; Mills 1987; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Rooney 1991; Schädelin 1988), but all the other 23 trials did not describe the process of randomisation.

Allocation could not be foreseen in 5 trials (Busch 2009; Miller 2004; Møller 1997; Schädelin 1988; Spruance 1999), while it was unclear if allocation was concealed in the other 27 trials.

Blinding

Twenty‐six trials blinded both the investigators and participants (Altmeyer 1991; Baker 2003; Bernstein 1994; Bernstein 1997; Bolla 1985; Busch 2009; Gibson 1986; Ho 1984; Miller 2004; Mills 1987; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Pedersen 2001; Raborn 1997; Raborn 1998; Redman 1986; Rooney 1993; Russell 1978; Schädelin 1988; Senti 2013; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b; Spruance 1991c; Spruance 1999; Thein 1984), while 5 trials did not blind them (de Carvalho 2010; Gilbert 2007; Pfitzer 2005; Rooney 1991; Schindl 1999). The de Carvalho 2010 trial compared laser treatments with no interventions. The Schindl 1999 trial performed the placebo irradiation in the same manner as in the laser group except that the laser was not turned on. However, laser irradiation might produce the sensation of sound and heat that could have been sensed by the participants. The Gilbert 2007 trial compared episodic and suppressive valaciclovir regimens. The Pfitzer 2005 trial compared hypnotherapy with no hypnotherapy. The Rooney 1991 trial compared a sunscreen with placebo solution, but the placebo recipients had sunburn while none of the sunscreen recipients had sunburn. Thus, the participants and researchers might have known the assigned treatments. It was unclear if the investigators and participants were blinded in the Duteil 1998 trial.

Outcome assessment was blinded in 27 trials (Altmeyer 1991; Baker 2003; Bernstein 1994; Bernstein 1997; Bolla 1985; Busch 2009; Gibson 1986; Ho 1984; Miller 2004; Mills 1987; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Pedersen 2001; Raborn 1997; Raborn 1998; Redman 1986; Rooney 1993; Russell 1978; Schädelin 1988; Schindl 1999; Senti 2013; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b; Spruance 1991c; Spruance 1999; Thein 1984) and unblinded in 4 trials (de Carvalho 2010; Gilbert 2007; Pfitzer 2005; Rooney 1991). It was unclear if the outcome assessors were blinded in the other trial (Duteil 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in 17 trials because of a low or null dropout rate (Baker 2003; Busch 2009; de Carvalho 2010; Miller 2004; Mills 1987; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Pedersen 2001; Raborn 1997; Raborn 1998; Rooney 1991; Rooney 1993; Schindl 1999; Schädelin 1988; Senti 2013; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1999). On the other hand, the risk of attrition bias was high in two trials because of a high dropout rate (Gilbert 2007; Russell 1978). No dropouts or withdrawals were mentioned in the other 13 trials.

Selective reporting

A total of 18 trials reported both the prespecified primary efficacy and adverse outcomes (Altmeyer 1991; Baker 2003; Bernstein 1997; Bolla 1985; Busch 2009; de Carvalho 2010; Gibson 1986; Gilbert 2007; Ho 1984; Miller 2004; Møller 1997; Pazin 1979; Pfitzer 2005; Raborn 1998; Russell 1978; Schädelin 1988; Spruance 1988; Spruance 1999). We judged these 18 trials to be at a low risk of reporting bias.

The Schindl 1999 trial reported the median recurrence‐free interval, which was not a prespecified outcome in our review protocol. The study protocol of the Senti 2013 trial is available on the US National Institutes of Health ongoing trials register (identifier: NCT00914745). The prespecified primary outcome (the number of herpes labialis relapse) has been reported. However, the exact numerical data were not provided; the authors only provided the data in plots. We therefore judged the two trials to be at an unclear risk of bias.

A total of 10 trials did not report adverse events (Bernstein 1994; Duteil 1998; Mills 1987; Redman 1986; Rooney 1991; Rooney 1993; Spruance 1991a; Spruance 1991b; Spruance 1991c; Thein 1984). The Pedersen 2001 and Raborn 1997 trials did not fully report the details of outcome data. All of these 12 trials were marked as high risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

A total of nine trials had a high risk of other potential bias for various reasons including early termination (Bernstein 1994), no washout period (Gibson 1986; Gilbert 2007; Rooney 1993; Thein 1984), different baseline frequency of recurrence of HSL (Pedersen 2001; Russell 1978), lack of standardised follow‐up plan (Schindl 1999), and a low percentage of participants having a history of HSL (Schädelin 1988). We judged Spruance 1988 at a low risk of other potential bias because of the trialists' advice to participants on frequent use of a standard sunscreen and no relation between the occurrence of herpes labialis and the potential confounding factors.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13; Table 14; Table 15; Table 16; Table 17; Table 18; Table 19; Table 20

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral aciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis.

| Oral aciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips) Settings: ski sites and university hospitals Intervention: oral aciclovir (short‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Oral aciclovir (short‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ aciclovir 800 mg twice daily | Study population | RR 1.08 (0.62 to 1.87) | 237 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 171 per 1000 | 184 per 1000 (106 to 319) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 171 per 1000 | 185 per 1000 (106 to 320) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ aciclovir 400 mg twice daily | Study population | RR 0.26 (0.13 to 0.51) | 177 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low² | ‐ | |

| 364 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 (47 to 185) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 538 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 (70 to 274) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ aciclovir 200 mg 5 times/day | Study population | RR 0.46 (0.2 to 1.07) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low³ | ‐ | |

| 394 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (79 to 422) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 394 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (79 to 422) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by culture) ‐ aciclovir 400 mg twice daily | Study population | RR 0.05 (0 to 0.7) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low³ | ‐ | |

| 750 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (0 to 525) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 750 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (0 to 525) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention ‐ aciclovir 800 mg twice daily | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.7 to 1.38) | 239 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 363 per 1000 | 356 per 1000 (254 to 501) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 363 per 1000 | 356 per 1000 (254 to 501) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention ‐ aciclovir 400 mg twice daily | Study population | RR 2.3 (0.62 to 8.58) | 183 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low² | ‐ | |

| 33 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (20 to 280) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (12 to 172) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial. ²Downgraded two levels due to risk of bias and imprecision: the available evidence is limited to two randomised trials, with one having a high risk of other biases. ³Downgraded two levels due to risk of bias and imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial with a high risk of reporting bias.

Summary of findings 2. Oral aciclovir (long‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis.

| Oral aciclovir (long‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes simplex labialis Settings: a medical centre Intervention: oral aciclovir (long‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| placebo | Oral aciclovir (long‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by culture) | 1.40 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period | 0.40 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period | Not estimable | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ | ‐ |

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) | 1.80 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period | 0.85 episodes per participant per a 4‐month period | Not estimable | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ | ‐ |

| Duration of attack of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | ‐ | The mean duration of attack of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 3.6 lower (7.2 lower to 0 higher) | ‐ | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ | ‐ |

| Rate of adherence to the regimen of the preventative intervention | 99% of the prescribed study medication | 99% of the prescribed study medication | ‐ | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded two levels due to risk of bias and imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial with a high risk of reporting bias.

Summary of findings 3. Valaciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis.

| Valaciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes simplex labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes simplex labialis Settings: a university hospital Intervention: valaciclovir (short‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Valaciclovir (short‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of HSL during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.23 to 1.28) | 125 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 206 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (47 to 264) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 206 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (47 to 264) | |||||

| Incidence of HSL during use of the preventative intervention (by culture) | Study population | RR 0.47 (0.21 to 1.08) | 125 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 238 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (50 to 257) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 238 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (50 to 257) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 1.33 (0.71 to 2.5) | 125 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 206 per 1000 | 274 per 1000 (147 to 516) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 206 per 1000 | 274 per 1000 (146 to 515) | |||||

| Viral load (shedding) in saliva | Study population | RR 0.16 (0.02 to 1.26) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 103 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (2 to 130) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 103 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (2 to 130) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HSL: herpes simplex labialis; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial.

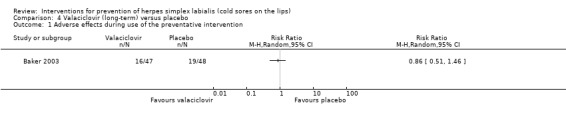

Summary of findings 4. Valaciclovir (long‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Valaciclovir (long‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: a university hospital Intervention: valaciclovir (long‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Valaciclovir (long‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 0.21 episodes per participant per month | 0.12 episodes per participant per month | Not estimable | 95 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ |

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.51 to 1.46) | 95 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 396 per 1000 | 340 per 1000 (202 to 578) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 396 per 1000 | 341 per 1000 (202 to 578) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial.

Summary of findings 5. Valaciclovir (suppressive regimen compared with episodic regimen) for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Valaciclovir (suppressive regimen compared with episodic regimen) for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: a university hospital Intervention: suppressive regimen Comparison: episodic regimen | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Episodic regimen | Suppressive regimen | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (number of recurrences per participant per month) | 0.1775 ± 0.1975 | 0.075 ± 0.1025 | The mean incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 0.1 lower (0.16 to 0.05 lower) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.78 to 1.87) | 152 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ | |

| 316 per 1000 | 382 per 1000 (246 to 591) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 316 per 1000 | 382 per 1000 (246 to 591) | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 2.86 ± 3.10 days | 1.78 ± 2.92 days | The mean duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 1.08 days shorter (2.16 lower to 0 higher) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| Severity (pain) of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 0.23 ± 0.32 | 0.14 ± 0.27 | The mean severity (pain) of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 0.09 lower (0.2 lower to 0.02 higher) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| Severity (maximum total lesion area) of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 10.52 ± 19.45 mm² | 5.14 ± 9.98 mm² | The mean severity (maximum total lesion area) of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 5.38 smaller (10.91 lower to 0.15 higher) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded three levels due to imprecision and multiple risk of biases in performance, detection, attrition, and other sources: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial with a high risk of biases.

Summary of findings 6. Famciclovir compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Famciclovir compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: multicentre Intervention: famciclovir Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Famciclovir | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ famciclovir 125 mg | Study population | RR 0.74 (0.5 to 1.11) | 120 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 517 per 1000 | 382 per 1000 (258 to 574) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 517 per 1000 | 383 per 1000 (259 to 574) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ famciclovir 250 mg | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.45 to 1.04) | 122 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 517 per 1000 | 357 per 1000 (232 to 537) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 517 per 1000 | 357 per 1000 (233 to 538) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) ‐ famciclovir 500 mg | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.56 to 1.21) | 121 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 517 per 1000 | 424 per 1000 (289 to 625) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 517 per 1000 | 424 per 1000 (290 to 626) | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention ‐ famciclovir 125 mg | Study population | HR 1.63 (0.84 to 3.15) | 47 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| See comment² | See comment² | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention ‐ famciclovir 250 mg | Study population | HR 1.59 (0.79 to 3.2) | 45 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| See comment² | See comment² | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention ‐ famciclovir 500 mg | Study population | HR 2.39 (1.23 to 4.63) | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| See comment² | Shortened by 2.8 days | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HR: hazard ratio; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the available evidence is limited to one single randomised trial. ²Data unavailable.

Summary of findings 7. Levamisole compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Levamisole compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: a university hospital Intervention: levamisole Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Levamisole | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 2.7 ± 2.3 recurrences during a 6‐month period | The mean incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 2 lower (2.24 to 1.76 lower) during a 6‐month period | ‐ | 72 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | Of the 99 participants randomised, 27 (27.2%) did not complete the trial and were excluded from the analysis, with 19 (39.6%) in the levamisole group and 8 (15.7%) in the placebo group |

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention (leading to withdrawal) | Study population | See comment | 99 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | Risks were calculated from pooled risk differences | |

| 157 per 1000 | 395 per 1000 (227 to 566) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 157 per 1000 | 396 per 1000 (228 to 567) | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | 8.2 ± 2.8 days | The mean duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 0.7 days longer (0.22 to 1.18 longer) | ‐ | 72 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded three levels due to imprecision and attrition and other biases: the available evidence is limited to a single study with a high risk of attrition and other biases.

Summary of findings 8. Lysine compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Lysine compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips) Settings: a university hospital Intervention: lysine Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Lysine | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (number of recurrences per participant per month) | ‐ | The mean incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 0.04 lower (0.37 lower to 0.29 higher) | ‐ | 26 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded three levels due to imprecision and reporting and other biases: the available evidence is limited to a single study with a high risk of reporting and other biases.

Summary of findings 9. Topical aciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Topical aciclovir (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: ski sites and university hospitals Intervention: topical aciclovir (short‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topical aciclovir (short‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.48 to 1.72) | 271 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 304 per 1000 | 276 per 1000 (146 to 522) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 328 per 1000 | 298 per 1000 (157 to 564) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 1.17 (0.59 to 2.32) | 191 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low² | ‐ | |

| 135 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (80 to 314) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 135 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (80 to 313) | |||||

| Severity (aborted lesions) of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.19 to 5.57) | 52 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low² | ‐ | |

| 95 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (18 to 530) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 95 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (18 to 529) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis after use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 0.35 (0.13 to 0.94) | 181 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low² | ‐ | |

| 156 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 (20 to 146) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 156 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (20 to 147) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to risk of bias: the evidence is from two trials with a high risk of reporting bias. ²Downgraded two levels due to risk of bias and imprecision: the evidence is from a single trial with a high risk of bias.

Summary of findings 10. Topical aciclovir and 348U87 cream (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Topical aciclovir and 348U87 cream (short‐term) compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: research institutes Intervention: topical aciclovir and 348U87 cream (short‐term) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topical aciclovir and 348U87 cream (short‐term) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by culture) | Study population | RR 0.78 (0.19 to 3.14) | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ | |

| 154 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (29 to 483) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 154 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (29 to 484) | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (by clinical evaluation) | Study population | RR 1.46 (0.53 to 3.99) | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ | |

| 192 per 1000 | 281 per 1000 (102 to 767) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 192 per 1000 | 280 per 1000 (102 to 766) | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | ‐ | The mean duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention in the intervention groups was 2.5 days longer (1.39 shorter to 6.39 longer) | ‐ | 9 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| Severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (maximum lesion area) | ‐ | The mean severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (maximum lesion area) in the intervention groups was 73 larger (42.22 smaller to 188.22 larger) | ‐ | 9 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded three levels due to imprecision and reporting and other biases: the available evidence is from a single trial with a high risk of reporting and other biases.

Summary of findings 11. Topical foscarnet compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Topical foscarnet compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: medical centres Intervention: topical foscarnet Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topical foscarnet | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | RR 1.08 (0.82 to 1.4) | 295 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 408 per 1000 | 441 per 1000 (335 to 571) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 408 per 1000 | 441 per 1000 (335 to 571) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention (leading to discontinuation) | Study population | RR 2.96 (0.12 to 72.11) | 302 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention (application site reactions) | Study population | RR 2.47 (0.79 to 7.69) | 302 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 27 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 (21 to 205) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 27 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (21 to 208) | |||||

| Duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (healing time) | ‐ | The mean duration of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (healing time) in the intervention groups was 0.21 days shorter (1.68 shorter to 1.26 longer) | ‐ | 125 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ |

| Severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (mean lesion area) | ‐ | The mean severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (mean lesion area) in the intervention groups was 16 lower (38.96 lower to 6.96 higher) | ‐ | 124 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ |

| Severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (maximum lesion area) | ‐ | The mean severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (maximum lesion area) in the intervention groups was 30 lower (72.64 lower to 12.64 higher) | ‐ | 124 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ |

| Severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (duration of pain) | ‐ | The mean severity of attack of recurrent herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention (duration of pain) in the intervention groups was 0.1 higher (1.11 lower to 1.31 higher) | ‐ | 113 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Downgraded one level due to imprecision: the available evidence is from a single trial.

Summary of findings 12. Topical 1,5‐pentanediol compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis.

| Topical 1,5‐pentanediol compared with placebo for prevention of herpes labialis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with recurrent herpes labialis Settings: study centres Intervention: topical 1,5‐pentanediol Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topical 1,5‐pentanediol | |||||

| Incidence of herpes labialis during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | Not estimable | 102 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | P > 0.05 calculated using the Mann‐Whitney test by the trialists | |

| 109 episodes out of 50 | 120 episodes out of 52 | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Adverse effects during use of the preventative intervention | Study population | Not estimable | 102 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Severity (blistering, swelling, or pain) of recurrence | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.91 to 1.2) | 224 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate¹ | ‐ | |

| 756 per 1000 | 794 per 1000 (688 to 908) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 756 per 1000 | 794 per 1000 (688 to 907) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||