Abstract

Objective

Tinnitus is the annoying sensation of sound perception without acoustic stimulus. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) is the habituation therapy used for the management of chronic subjective tinnitus. The objective of the study is to describe TRT and to evaluate its efficacy in patients with subjective tinnitus.

Methods

In total, 58 patients with tinnitus who did not respond to medications were enrolled in the TRT program. TRT included counseling as described in the neurophysiological model of tinnitus and sound therapy (aided or unaided) for six months. The tinnitus severity grade (TSG) 1–5, based on a validated tinnitus questionnaire score (TQS), and the visual analogue scale (VAS) score were documented before and after therapy.

Results

Before TRT, 53 patients (91.3%) exhibited TSG 3–5, and the average VAS score was 6.7±2.1. After TRT for two months, 49 patients (84.4%) showed TSG 1–3, and the average VAS score was 3.2±2.4. After six months of TRT, most of the patients found remarkable improvement in the symptoms, and 51 patients (87.9%) exhibited TSG 1–2, and the average VAS score was 2.1±2.6. Statistically significant difference was found in TSG and VAS score before and after TRT. Statistically significant correlation was observed between TSG and VAS score.

Conclusion

TRT is an useful approach for amelioration of tinnitus. TQS is a very effective, cheap, and easy method to help otologists to grade the patients as per the severity of symptoms.

Keywords: Tinnitus, tinnitus retraining therapy, treatment outcome, visual analogue scale

Introduction

Tinnitus can be a potentially debilitating symptom physically, emotionally, and socially. The underlying pathophysiology is unclear, which makes the treatment disputable. There are a variety of treatment modalities for chronic subjective tinnitus, but very few have stood the test of time (1). Pharmacotherapy, including the use of lidocaine and tranquilizers, surgical treatment (1), and trans-cranial magnetic stimulation (2) has been exploited for its management. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) was first described by Jastreboff and Jastreboff (3). It is a practical implementation of neurophysiological model of tinnitus that includes counseling and sound therapy (aided or unaided). Sound therapy aims to decrease the dissimilitude between phantom sound and background neuronal activity. It interferes with the brain’s ability to detect the tinnitus signal, and thereby, reduces the abnormal gain in the auditory system (3). In this study, we assessed the efficacy of TRT based on tinnitus questionnaire score (TQS) and visual analogue scale (VAS) score.

Methods

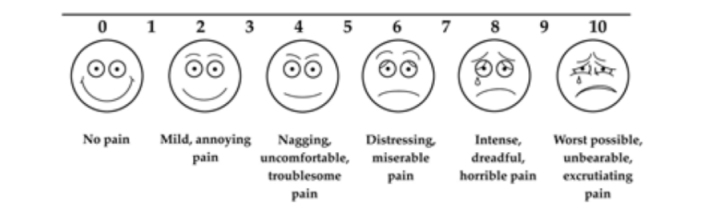

This study is a prospective, randomized, single blinded study including 58 patients with subjective tinnitus, who visited our institution during 2015–2016. The Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (approval number: SKNMC No/Ethics/App/2014/236, dated 23/07/2014). The study was performed according to the ethical standards and guidelines of Helsinki Declaration. Patients who did not experience relief with medication and had chronic (>1year), non-pulsatile, continuous, or unilateral tinnitus were included in the TRT program. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Each patient underwent clinical and audiological examinations. Patients with tinnitus associated with middle ear disease or Meniere’s disease, general debility, or central tinnitus were excluded from the study. The age of the patient and the average duration of tinnitus were recorded. Pure tone audiometry (GSI 61-Innovative technologies USA) was performed to evaluate the parameters as follows: the mean hearing threshold of four frequencies (500, 1000, 2000, and 4000Hz), the pitch match test determining the pure tone frequency most similar to the phantom sound, and the loudness balance test obtaining the pure tone value (dB) giving equivalent loudness of tinnitus sound. TQS and the tinnitus severity grade (TSG), based on the tinnitus questionnaire sheet (Table 1, 2) and the VAS score (Figure 1) were documented before therapy. TRT was administered in the form of two strategies as per the neurophysiological model. First strategy was counseling and the second was sound therapy. Counseling was carried out by an otologist. It was aimed at eliminating the patients’ anxiety and increasing their knowledge about tinnitus. It included deep relaxation exercises and stress management. Sound therapy was administered in the form of relatively broad-band, neutral sound, produced by wearable ear-level devices, which included tinnitus maskers [broad-band sound generators (SGs)], hearing aids, or SG-hearing aid combination instruments. This was administered as per the hearing status of the patient. The severity of tinnitus was graded as 1–5 based on TQS (Table 2). The patients with grade 1 tinnitus were treated with counseling alone and those with grade 2 and onwards were treated with the combination of counseling and sound therapy. TQS and TSG, based on Tinnitus Questionnaire sheet (Table 1), and the VAS score were documented two and six months after therapy. VAS score was documented from 0–10 (in terms of volume and disturbance); 0 score indicates no tinnitus and 10 score indicates catastrophic tinnitus (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Tinnitus questionnaire sheet and score

| Sr. No | Question | Yes (A) |

Sometimes (B) |

No (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Because of your tinnitus, is it difficult for you to concentrate? | |||

| 2 | Does the loudness of your tinnitus make it difficult for you to hear people? | |||

| 3 | Does your tinnitus make you angry? | |||

| 4 | Does your tinnitus make you feel confused? | |||

| 5 | Because of your tinnitus, do you feel desperate? | |||

| 6 | Because of your tinnitus, do you have trouble falling to sleep at night? | |||

| 7 | Do you feel as though you cannot escape your tinnitus? | |||

| 8 | Does your tinnitus interfere with your ability to enjoy your social activities (such as going out to dinner, to the movies)? | |||

| 9 | Because of your tinnitus, do you feel frustrated? | |||

| 10 | Does your tinnitus interfere with your job or household responsibilities? | |||

| 11 | Because of your tinnitus, do you find that you are often irritable? | |||

| 12 | Because of your tinnitus, is it difficult for you to read? | |||

| 13 | Because of your tinnitus, is it difficult for you to watch television? | |||

| 14 | Do you feel that your tinnitus problem has placed stress on your relationships with members of your family and friends? | |||

| 15 | Do you feel that you have no control over your tinnitus? | |||

| 16 | Does your tinnitus get worse when you are under stress? | |||

| 17 | Does your tinnitus make you feel insecure? | |||

| 18 | Because of your tinnitus, do you often feel tired? | |||

| 19 | Does your tinnitus make you feel anxious? | |||

| 20 | Does your tinnitus make it difficult to relax in a quiet room? | |||

| 21 | Does tinnitus causes you to avoid noisy situations. | |||

| 22 | Does tinnitus contributes to a feeling of general ill health | |||

| 23 | Does your tinnitus makes you panicky | |||

| 24 | Does your tinnitus has led you to think about suicide | |||

| 25 | Does tinnitus interferes with your ability to tell where sounds are coming from. | |||

| Total | A | B | C | |

| x4 | x2 | x0 | ||

| Total Score=(Ax4)+(Bx2)+(Cx0) | ||||

Tinnitus questionnaire score:

Table 2.

Tinnitus severity grade according to tinnitus questionnaire score

| TSG | TQS | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–16 | Slight: Only heard in quiet environment, very easily masked. No interference with sleep or daily activities. |

| 2 | 18–36 | Mild: Easily masked by environmental sounds and easily forgotten with activities. May occasionally interfere with sleep but not daily activities. |

| 3 | 38–56 | Moderate: May be noticed, even in the presence of background or environmental noise, although daily activities may still be performed. |

| 4 | 58–76 | Severe: Almost always heard, rarely, if ever, masked. Leads to disturbed sleep pattern and can interfere with ability to carry out normal daily activities. Quiet activities affected adversely. |

| 5 | 78–100 | Catastrophic: Always heard, disturbed sleep patterns, difficulty with any activity. |

TSG: tinnitus severity grade; TQS: tinnitus questionnaire score

Figure 1.

Model of visual analogue scale used

Based on the improvement in the TQS and VAS score, the clinical efficacy of TRT was analyzed. For statistical evaluation of TSG before and after TRT, Pearson’s Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact probability tests were used. Comparison between VAS score before and after TRT was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (SPSS software - SAS Institute, USA). A p value of <0.05 was considered to be significant. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were added if p values were less than 0.05. Correlation between TQS and VAS was obtained through the Spearman’s coefficient correlation. This coefficient varied between −1 to +1. Closer the value is to −1 or +1, stronger is the association, and closer it is to zero, weaker is the association. If the value is closer to −1, it suggests an inverse association between the variables.

Results

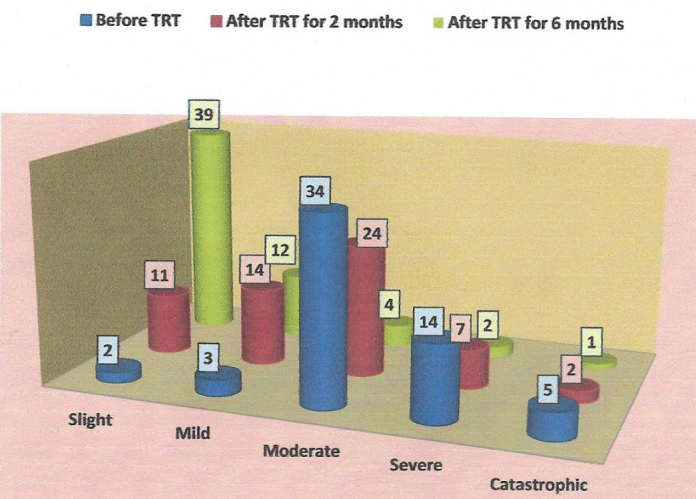

A total of 58 patients (32 males and 26 females) with median age of 62 y (28–75 years) received TRT for six months. The average duration of tinnitus was 17 months (12–28 months). The average hearing threshold, tinnitus pitch, and tinnitus loudness were 33.25 (standard deviation±10.6) dB, 4000 Hz, and 55 dB, respectively (Table 3). Tinnitus was most commonly associated with presbycusis (n=35). Sudden deafness was observed in two patients, noise-induced hearing loss in one patient, and trauma in four patients. In 16 patients, the tinnitus was idiopathic. The TSG based on TQS was documented before TRT and two and six months after TRT (Table 4, Figure 2).

Table 3.

Audiological findings of patients

| Frequency | Mean Pure tone thresholds db (SD) of the affected ear |

|---|---|

| 500 Hz | 21 (9.6) |

| 1000 Hz | 33 (16.1) |

| 2000 Hz | 38 (7.9) |

| 4000 Hz | 41 (8.8) |

| Mean | 33.25 (10.6) |

Db: decibels, SD: standard deviation

Table 4.

Tinnitus severity grade before and after tinnitus retraining therapy

| Tinnitus Severity Grade (TSG) | Tinnitus Questionnaire Score (TQS) | Before TRT (Number of patients) (n=58) | After TRT at 2 months (Number of patients) (n=58) | After TRT at 6 months (Number of patients) (n=58) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ( Slight) | 0–16 | 2 | 11 | 39 |

| 2 ( Mild) | 18–36 | 3 | 14 | 12 |

| 3 (Moderate) | 38–56 | 34 | 24 | 4 |

| 4 (Severe) | 58–76 | 14 | 7 | 2 |

| 5 (Catastrophic) | 78–100 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 58 | 58 | 58 |

TRT: tinnitus retraining therapy

Figure 2.

Graph showing tinnitus severity grade before and after tinnitus retraining therapy

Statistical analysis with Pearson’s Chi square test showed the Chi square value of 74.11 with 3 degree of freedom and 95 degree CI; Cramer’s V=0.6782. The p value was <0.00001. Fisher’s exact probability test (cross validated) showed p value of 0.000. Statistically significant difference was noted in TSG before TRT and after TRT for 6 months.

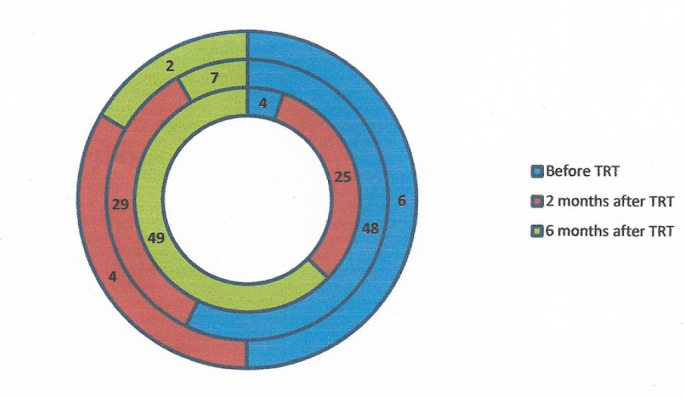

Visual analogue scale score was documented before TRT and at two and six months after TRT (Table 5, Figure 3). The average VAS score before TRT was 6.7±2.1. After TRT, at 2 months follow up, the average VAS score was 3.2±2.4, and at 6 months, it was 2.1±2.6. The Mann–Whitney test showed U-value of 26 and Z-score of 3.82543. The p value was found to be 0.00012. Statistically significant difference was observed in the VAS scores before TRT and after TRT. According to the Spearman’s relation coefficient, we observed that there is a significant correlation between TQS and VAS score (rs=0.684; p=0.0001; n=58). Therefore, higher the VAS score, higher is the TQS and TSG.

Table 5.

Visual analogue scale score before and after tinnitus retraining therapy

| VAS score | Before TRT (Number of patients) (n=58) | After TRT at 2 months (Number of patients) (n=58) | After TRT at 6 months (Number of patients)(n=58) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 | 4 | 25 | 49 |

| 4–7 | 48 | 29 | 7 |

| 8–10 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 58 | 58 | 58 |

VAS: visual analogue scale; TRT: tinnitus retraining therapy

Figure 3.

Ring graph showing visual analogue scale score in patients before and after tinnitus retraining therapy

Discussion

Tinnitus represents a symptom of an underlying condition rather than a disease itself. The most common type of tinnitus is subjective tinnitus, which is sensorineural in origin. The pathophysiological cause of tinnitus remains unclear, but a widely accepted theory states that it involves hyperactive hair cells or nerve fibers activated by a chemical imbalance across cell membrane or by the decoupling of stereocilia (1, 4). TRT was described by Jastreboff and Hazell in early 1990s. It is the practical implementation of the neurophysiological model of tinnitus proposed by Jastreboff in 1980 (1, 4). According to this model, in patients with chronic subjective tinnitus, the limbic system and the autonomous nervous system prioritizes tinnitus sound, and the sound is perceived as loud and persistent. The end goal of TRT is the complete habituation of phantom sound. Counseling should be conducted preferably by an otologist because a background knowledge of auditory pathophysiology and hearing loss definitely aids in achieving successful targeted therapy. (4). We included deep relaxation exercises and stress management in the counseling so as to relieve patients’ anxiety. Tinnitus was not the focus of attention for this therapy because the goal was to achieve better relaxation and the ability to sleep. This in turn improved the patients’ quality of life and helped in achieving rapid relief and sense of control. Stress management included Tai Chi, yoga, meditation, muscle relaxation, and visual imagery. The training sessions were conducted at the yoga center of our Institute.

Once the emotional response is removed, habituation follows. The second component of TRT is sound therapy. It aims to remove the tinnitus from conscious perception so as to achieve complete habituation. Desensitization of limbic system and autonomous nervous system is performed by sensory stimulus repetition. After successful execution of the first strategy, the second strategy can be implemented. (5) In the sound therapy, we use a constant low-level broad-band sound (white noise generator) to reduce the difference between phantom sound and background neuronal activity, thereby reducing the activation of limbic system and autonomous nervous system. This in turn reduces the tinnitus detectability at the subconscious level. After successful implementation of the two strategies, the tinnitus signal gets habituated from negative reactions (i.e. limbic and sympathetic portions of the autonomous nervous systems) and from conscious perception (5, 6).

Sound generator is a small device that resembles a hearing aid. We used SG in patients with normal hearing or mild sensorineural hearing loss. For severe hearing loss, hearing aids with built-in SGs were used. In our study, we observed a step ladder improvement in the TSG, with maximum benefit achieved at six months after therapy. Jastreboff model states that the benefits of TRT treatment increases over time (3). Lux-Wellenhof and Hellweg (7) reported a continued improvement and a sustained benefit over five years, even after the cessation of formal treatment with TRT. In this study, we evaluated the patients till six months after TRT; therefore, we were unable to conclude about further benefits. We propose to continue this research and report the long-term benefits of TRT.

Conclusion

Tinnitus retraining therapy is a useful approach for the amelioration of tinnitus. With continued treatment, TRT may produce best effects. TRT is more effective if patients are graded as per the severity of tinnitus. TQS is a very effective, cheap, and easy method to help the otologist in grading the patients as per the severity of symptoms. In particular, patients with high grade of difficulty with tinnitus benefit most from TRT, which helps them attain lower levels of handicap and severity.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Ethics Committee of Smt. Kashibai Navale Medical College.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patients who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - S.V.N., K.J.S.; Design - S.V.N., K.J.S.; Supervision - S.V.N., K.J.S.; Materials - S.N.; Data Collection and/or Processing - S.N., K.S.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - S.N., K.S.; Literature Search - S.N.; Writing - S.N.; Critical Reviews - S.N., K.S.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Grewal R, Spielmann PM, Jones SE, Hussain SS. Clinical efficacy of tinnitus retraining theapy and cognitive behavioural theapy in the treatment of subjective tinnitus: a systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128:1028–33. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114002849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariizumi Y, Hatanaka A, Kitamura K. Clinical prognostic factors for tinnitus retraining therapy with a sound generator in tinnitus patients. J Med Dent Sci. 2010;57:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jastreboff P, Jastreboff M. Tinnitus retraining therapy: A different view on tinnitus. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;68:23–9. doi: 10.1159/000090487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry JA, Schechter MA, Nagler SM, Fausti SA. Comparison of tinnitus masking and tinnitus retraining therapy. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13:559–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parazzini M, Del Bo L, Jastreboff M, Tognola G, Ravazzani P. Open ear hearing aids in tinnitus therapy: an efficacy comparison with sound generators. Int J Audiol. 2011;50:548–53. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.572263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer CA, Berry JL, Brozoski TJ. The effect of tinnitus retraining therapy on chronic tinnitus: A controlled trial. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;4:166–77. doi: 10.1002/lio2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lux-Wellenhof G, Hellweg FC. In: Patuzzi R, editor. Longterm follow up study of TRT in Frankfurt; Proceedings of the 7th International Tinnitus Seminar; Crawley, Western Australia. 2002. pp. 277–9. [Google Scholar]