Abstract

Background:

Several small studies have suggested that spinal manipulation may be an effective treatment for reducing migraine pain and disability. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to evaluate the evidence regarding spinal manipulation as an alternative or integrative therapy in reducing migraine pain and disability.

Methods:

PubMed and the Cochrane Library databases were searched for clinical trials that evaluated spinal manipulation and migraine related outcomes through April 2017. Search terms included: migraine, spinal manipulation, manual therapy, chiropractic, and osteopathic. Meta-analytic methods were employed to estimate the effect sizes (Hedges’ g) and heterogeneity (I2) for migraine days, pain, and disability. The methodological quality of retrieved studies was examined following the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

Results:

Our search identified 6 RCTs (pooled n=677; range of n=42–218) eligible for meta-analysis. Intervention duration ranged from 2–6 months; outcomes included measures of migraine days (primary outcome), migraine pain/intensity and migraine disability. Methodological quality varied across the studies. For example, some studies received high or unclear bias scores for methodological features such as compliance, blinding, and completeness of outcome data. Due to high levels of heterogeneity when all six studies were included in the meta-analysis, the one RCT performed only among chronic migraineurs was excluded. Heterogeneity across the remaining studies was low. We observed that spinal manipulation reduced migraine days with an overall small effect size (Hedges’ g = −0.35, 95% CI: −0.53, −0.16, p<0.001) as well as migraine pain/intensity.

Conclusions:

Spinal manipulation may be an effective therapeutic technique to reduce migraine days and pain/intensity. However, given the limitations to studies included in this meta-analysis, we consider these results to be preliminary. Methodologically rigorous, large-scale RCTs are warranted to better inform the evidence base for spinal manipulation as a treatment for migraine.

Keywords: spinal manipulation, migraine, pain, disability

Background:

Thirty-eight million adults in theUnited States are estimated to be migraine sufferers, of these, 91% experience migraine-associated disability.1–3 Traditionally, abortive and prophylactic medications are first-line treatment for migraine therapy, with most migraineurs treating their headaches at the onset of symptoms.2 However, approximately 40% of those with episodic migraine have unmet treatment needs.4 Of these patients, one-third report dissatisfaction with current treatment and about half report moderate or severe headache-related disability.4 In addition, commonly prescribed rescue medications (e.g. analgesics, ergots, triptans, and opioids) may increase the risk of medication overuse headaches, allodynia, and dependence.5 The limitations to current pharmacological therapies has highlighted the need to explore alternative or integrative treatment for migraine.

One potential non-pharmacological approach to treatment of migraine patients is spinal manipulation, a manual therapy technique most commonly used by doctors of chiropractic, but also practiced by some physical therapists and osteopathic physicians. A recent cross-sectional survey using data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey estimated that approximately 15.4% of individuals with migraine have used chiropractic care (which can include spinal manipulation) in the past 12 months.6 Given the prevalence of migraine, this may translate into a substantial disease burden in chiropractic care clinics because 94% of spinal manipulation for which reimbursement is sought in the U.S. is delivered by chiropractors.7 For example, a survey of Australian chiropractors also found that 53% of chiropractors reported managing patients with migraine “often” and 40.9% of chiropractors reported managing patients with migraine “sometimes”.8 In the United States, approximately 12% of patients seeking treatment from a chiropractor report headache as their chief complaint.9 Given the prevalence of migraine patients seeking chiropractic care and the need for evidence-based non-pharmacological approaches to treat migraine, there is a need to understand whether spinal manipulation, an integral component to chiropractic care, is an effective non-pharmacological approach for the treatment of migraine headaches.

Three systematic reviews have examined the effects of spinal manipulation on migraine10–12, but these reviews included only three randomized controlled trials13–15 and did not include a meta-analysis of the effects seen in these studies. Since the publication of these reviews, additional randomized controlled trials on spinal manipulation have been conducted.16–18 The aim of this study is to provide a synthesis of available clinical trials by using a systematic review and to perform a preliminary meta-analysis examining the effects of spinal manipulation on migraine frequency, pain, and disability.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search and inclusion criteria

Our literature search strategy and inclusion criteria were specified a priori. In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, we searched the Cochrane Library and PubMed, which includes MEDLINE, for relevant articles from inception through April 2017. The following search terms were used: spinal manipulation, osteopathic, chiropractic, manual therapy, and migraine. The search was limited to articles identified as clinical trials in PubMed. To expand the selection, we also manually searched the reference lists of all retrieved articles.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

We included randomized clinical trials (RCTs) where the primary intervention was spinal manipulation and the primary disorder investigated was migraine headaches. No exclusions were made on the basis of provider type (e.g. chiropractic vs osteopathic) or area of the spine manipulated.

2.3. Data Extraction and Syntheses

Data was extracted independently by two researchers (AH, RS) utilizing a standardized template generated in Microsoft Excel. Admissible data included the study design, duration and frequency of the intervention, sample size, type of control, and outcome measures. The decisions about what data to extract were made a priori.

2.4. Quality assessment

Three authors (AH, KO, PR) individually assessed the methodological quality of RCTs using the 7-item Cochrane Collaboration Tool for assessing risk of bias.19 The criteria were selected a priori and included: (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants, (4) blinding of outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective reporting (including reporting of all outcomes and specifying a primary outcome), and (7) other bias. For “other bias” we evaluated the studies for the following criteria: group similarity at baseline with regards to the outcome measures, similarity in co-intervention, compliance, timing of outcome assessments, rationale for sample size, rationale for control group, and intervention description (see supplemental Table 1 for full descriptions of these items). Per established criteria, the evaluated domains were judged as low risk, high risk, or unclear bias. In the case of evaluation discrepancies, the authors discussed and came to an agreement.

2.5. Safety monitoring

We reviewed the studies for the inclusion of formal protocols which methodically monitored adverse events, and whether any adverse events reported were a direct result of the intervention.

2.6. Data analysis and syntheses

For each study, the mean and standard deviation (SD) values at baseline and post-intervention for the primary and secondary outcomes were extracted. Other data extracted included t score or p-value between groups and the sample size (N) in each group. If such data were not available, the standard error values, confidence intervals or medians with interquartile ranges were translated into mean and SD following suggested statistical formulas.19, 20 The most common outcomes assessed across all studies were migraine days and measures of migraine-related pain and disability. Migraine days was used as our primary outcome.

Effect sizes (Hedges’ g) and 95% confidence intervals using random and fixed effects models were calculated by Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.0 software (CMA v3, Biostat, Inc. USA). Effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are considered small, medium, and large respectively.21 Heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the Q value and I2 statistics. A low p-value for the Q statistic or an I2 ratio greater than 75% indicated heterogeneity across the studies. The pooled effect sizes for the most common outcomes were calculated. For the primary analyses, we calculated pooled effect sizes comparing the intervention group to all possible control groups. If an article had two different control groups, the sample size of the intervention group was divided by 2 to avoid overweighting the study. In secondary analyses, subgroup analyses were performed for active controls and passive controls.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

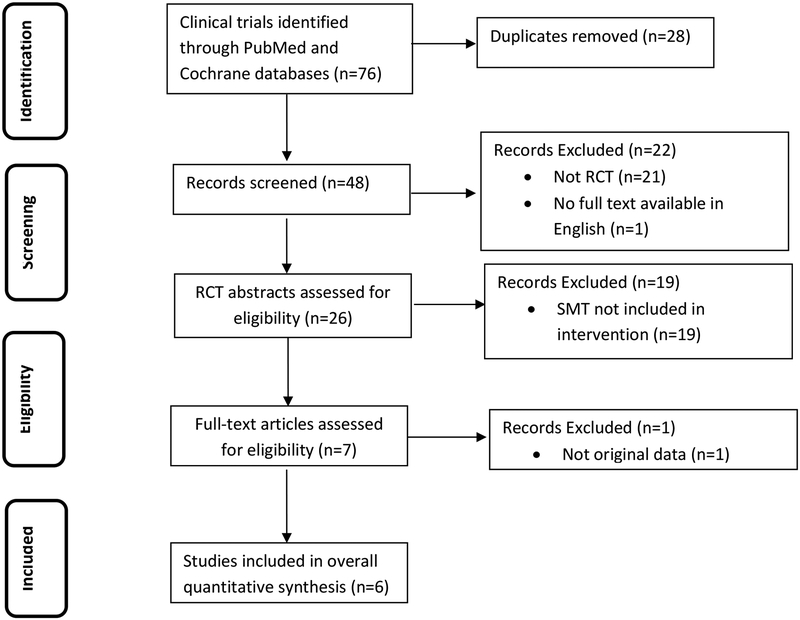

Our literature search is summarized in Figure 1. The initial search identified 76 clinical trials. The titles and abstracts were assessed for inclusion. After the removal of duplicate records, 48 remained for further assessment. Of those, 21 were not RCT studies and 1 text was unavailable in English. The remaining 26 studies were further assessed for eligibility. Of the remaining clinical trials, 19 did not use spinal manipulation as a treatment and 1 did not present original data. The 6 remaining clinical trials13–18 were included in the overall quantitative synthesis, 3 of which have been included in previous systematic reviews.13–15 Two of the trials were registered in clinicaltrials.gov.16, 17

Figure 1.

Study identification process following PRISMA guidelines.

3.1.1. Participant characteristics and study setting

The 6 clinical trials identified in our literature review are summarized in Table 1. A total of 677 patients were randomized into these studies; 670 patients had baseline assessments and could be included in analyses. The average age of participants at baseline was 39.3 years and 75.0% were female. All studies allowed patients to continue use of their current medications. Five studies enrolled episodic migraine patients and the minimum number of migraine attacks per month needed to be eligible ranged from 1 to 4.13–15, 17, 18 Only one study enrolled patients diagnosed with chronic migraine according to ICHD-II criteria.16

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Main Author (country) | Study Type | Sample | Gender (M/F) | Intervention | Number of Treatments | Duration (months) | Control Group | Measured Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerritelli 2015 (Italy) | RCT | 105 | 36/69 | SM | 8 | 6 | (1) Sham + medication (2) medication only | HIT-6*, migraine days, pain intensity, medication use, functional disability |

| Chaibi 2017 (Norway) | RCT | 104† | 14/83 | SM | 12 | 3 | (1) Sham (2) Usual pharmacological management | migraine days*, duration*, intensity, headache index*, medication use |

| Voigt 2011 (Germany) | RCT | 42 | 00/42 | SM | 5 | 2.5 | Usual pharmacological management | MIDAS*, SF-36 (some domains*), German “Pain Questionnaire”*, HRQOL, migraine days, pain intensity* |

| Tuchin 2000 (Australia) | RCT | 123 | 39/86††† | SM | 16 | 2 | Detuned interferential therapy (placebo) | migraine frequency*, intensity, duration*, disability*, associated symptoms, medication use* |

| Nelson 1998 (USA) | RCT | 218†† | 46/172 | SM | 14 | 2 | (1) Medication (2) spinal manipulation + medication | Headache Index score (including headache frequency and severity), SF-36, medication use |

| Parker 1978 (Australia) | RCT | 85 | 33/52 | SM | 8–16 | 2 | Cervical mobilization | duration, pain, disability, migraine frequency |

Note. HIT-6,Headache Impact Test; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment; SF-36, Short Form-36; HRQOL, Health Related Quality of Life; HI score, Headache Index; EPI, Eysenck Personality Inventory; GHQ-30, 30-item General Health Questionnaire; SM, spinal manipulation

Indicates outcome significantly improved comparing spinal manipulation to the control group.

Note: This is number of participants who were randomized. One participant in the spinal manipulation group, one participant in the sham group, and five participants in the usual pharmacological management group dropped out prior to baseline assessment.

Note: This is number of participants who were randomized. Five participants in the medication group did not accept their treatment assignment.

127 subject agreed to enter the trial and 123 subjects completed the trial. This study reported gender for 125 subjects.

3.1.2. Intervention and control group characteristics

All studies used a parallel-arm design in which participants were assigned to a spinal manipulation treatment group or to a control group (either active or passive controls). While there was heterogeneity in the specific type of spinal manipulation techniques used in each study, the techniques used in the treatment groups were applied with the intent to influence the function of joints and the tautness of soft tissue. The spinal manipulations were performed by a chiropractor in three studies13, 15, 17, an osteopathic physician in two studies16, 18, or by either a medical practitioner, physiotherapist, or chiropractor in one study.14 The duration of the intervention ranged from 2 to 6 months, with the number of treatments ranging from 8 to 16. The type of control group used varied across the studies. Five of the six studies employed active controls where the intervention group was compared to sham therapy16, 17, cervical mobilization (movement of joints within normal limitations)14, detuned interferential therapy (which served as a “placebo” therapy)15, or a combination of spinal manipulation and amitriptyline treatment.13 In addition to having an active control, three studies also contained a second “passive” control arm where patients were allowed to either continue usual pharmacological therapy17, change medications as their physician directed16, or were assigned to take amitriptyline.13 The sixth study only used a “passive” control group and compared those receiving the intervention to those not receiving spinal manipulation, sham treatment, or physical therapy.18 In this study, all participants were allowed to continue their previously prescribed medications.18

3.1.3. Outcome measures

Of the six studies, five assessed their outcomes through the use of migraine diaries.13–17 In addition to using migraine diaries, two studies also administered questionnaires to assess some outcomes at set time points during the study.13, 16 One study only assessed outcomes through questionnaires.18 Migraine days per month or the frequency of migraine attacks was assessed in all studies and was our primary outcome. We also analyzed migraine intensity or migraine pain13–18 and measures of migraine disability.14–16, 18

3.1.4. Adverse effects

Of the 6 RCTs, only 2 studies explicitly reported adverse events or adverse effects.16, 17 The first reported that adverse effects were an item in headache diaries but provided no additional reporting details. No adverse effects were reported during this trial.16 The second study reported that all adverse events were recorded after each intervention session but it was unclear how adverse events were recorded for those in the usual pharmacological management group. Few adverse events were observed and none were considered serious or severe.17 A third study reported the prevalence of neck pain among those receiving spinal manipulation but not among the other groups and the authors did not report other adverse events.15

3.1.5. Risk of bias assessment

Table 2 displays the results from our risk of bias assessment. Only three studies were judged to be low risk of bias for the random sequence generation and for allocation concealment.13, 16, 17 Given the nature of the intervention and control treatment chosen, most studies were unable to blind participants.13–15, 18 Two studies did use a “sham” spinal manipulation for one of their control groups which allowed blinding of participants in the intervention and “sham” groups but not those in medication only or usual pharmacological management control groups.16, 17 Both studies also provided information to demonstrate that blinding of participants in the “sham” group was successful.16, 17 One study found that none of the patients in the sham group were able to correctly guess the nature of their treatment.16 The other study asked participants after each session whether they believed they had received spinal manipulation. Over 80% of participants believed they had received spinal manipulation regardless of group allocation.17 Because participants self-reported all outcomes, lack of blinding of participants directly impacted our assessment of blinding of the outcomes. Only the two studies which used “sham” groups received low risk of bias scores for blinding of the outcomes.16, 17 Some studies did mention that the analyst was blinded to the treatment assignment of participants17 or that the outcomes assessor was blinded.16 Only two studies provided enough information to show low attrition rates during the course of the study (“incomplete outcome data” criteria).14, 16 All studies provided information on all outcome measures mentioned in the methods section, but three studies did not specify a primary outcome.14, 15, 18 For other biases, the most noticeable result was that five studies provided insufficient detail to determine participant compliance. Three studies did not provide sample size rationale.14, 15, 18

Table 2.

Risk of bias summary for included studies.

| Study | Random sequence | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting - A | Selective reporting - B | Differences at baseline | Co-interventions similar | Compliance | Timing of outcomes | Rationale for sample size | Rationale for control group | Intervention description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerritelli 2015 | L | L | L | H | L | UC | L | L | L | L | H | UC | L | L | L | H | L |

| Chaibi 2017 | L | L | L | H | L | UC | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Nelson 1998 | L | L | H | UC | H | L | L | L | L | UC | L | L | L | L | |||

| Tuchin 2011 | H | H | H | UC | UC | L | H | L | UC | UC | L | H | L | L | |||

| Voigt 2011 | UC | UC | H | UC | UC | L | H | L | L | UC | L | H | UC | L | |||

| Parker 1978 | UC | UC | UC | UC | UC | L | H | L | L | UC | L | H | L | L | |||

Note: L=Low risk of bias, H=High risk of bias, UC=Unclear (see Supplemental Table 1 for criteria for each rating); split boxes include rating for first and second control group as listed in Table 1.

3.2. Effects of spinal manipulation on migraine days/frequency of migraine.

All six studies provided information on migraine days per month15–17 or in the past 3 months18, percentage of days with headache in the past four weeks13 or the “mean frequency of attacks”.14 The originally planned a priori meta-analysis including all six studies using a random effects model indicated that spinal manipulation had a greater impact on reducing the number of migraine days compared to controls with an overall large effect size (Hedges’ g = −1.16, 95% CI: −1.94, −0.39, p=0.003) (Supplemental Table 1). However, heterogeneity across the six studies was high (I2 ratio = 93.80%) and appeared to be driven by the study by Cerritelli et al., which only enrolled chronic migraineurs and showed effect sizes that were substantially larger than the other studies. Due to concerns that arose during peer review that even a random effects model would not adequately capture this between study heterogeneity across all six studies, we decided post-hoc (i.e. after performing our initial analyses) to exclude the study by Cerritelli et al from our main analyses. Results from analyses including this study can be found in the Supplement and generally were of stronger magnitude than those presented here.16 After excluding this study, heterogeneity across the remaining studies was low (Q statistic=3.61, p-value=0.72; I2 ratio = 0) and we decided post hoc to use a fixed effects model. The meta-analysis of the remaining five studies indicated that spinal manipulation had a greater impact on reducing the number of migraine days compared to controls with an overall small effect size (Hedges’ g=−0.35, 95% CI: −0.53, −0.16, p-value<0.001) using a fixed effects model. As a sensitivity analysis, we also performed this analysis using a random effects model and observed the same results (Hedges’ g=−0.35, 95% CI: −0.53, −0.16, p-value<0.001). The effect size was similar when the analysis was restricted to studies which compared the intervention group to active controls (4 studies; Hedges’ g=−0.41, 95% CI: −0.64, −0.17, p-value=0.001). The overall effect size was slightly smaller when comparing the interventional group to passive controls (3 studies; Hedges’ g=−0.25, 95% CI: −0.56, 0.06, p-value=0.117).

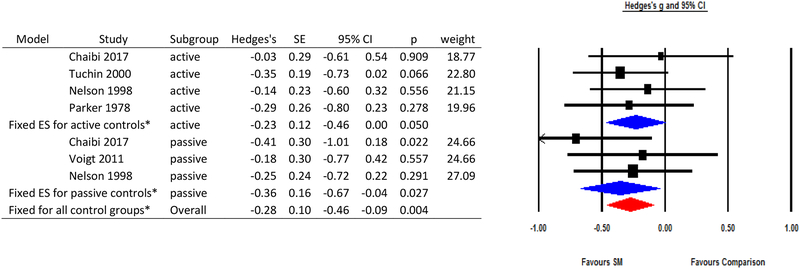

3.3. Effect of spinal manipulation on migraine pain or intensity

A measure of migraine pain or intensity was used in all studies usually through a Likert scale or visual analog scale. However, one study18 used MIDAS B and the German “Pain Questionnaire” to assess migraine pain. Analyses excluding the study by Cerritelli et al.16 observed that spinal manipulation had greater impact on reducing migraine pain or intensity with an overall small effect size (Hedges’ g=−0.28, 95% CI: −0.46, −0.09, p-value=0.004) from a fixed effects meta-analysis (Q statistic=3.26, p-value=0.77; I2=0). This effect was similar when restricting analyses to active control groups (Hedges’ g=−0.23, 95% CI: −0.46, 0, p-value=0.050) or to passive controls t (Hedges’ g=−0.36, 95% CI: −0.67, −0.04, p-value=0.027).

3.4. Effects of spinal manipulation on migraine disability

Only four studies provided information on migraine disability. Measures of disability varied across studies and included assessments of number of hours before returning to work15, “mean disability”14, disturbance in occupation due to migraine and days of disablement from MIDAS 118, and functional disability and the HIT-616. After excluding the study by Cerritelli et al16, we observed a small effect size in a fixed effects meta-analysis (Q statistic = 0.34, p-value=0.84; I2=0) (Hedges’ g=−0.16, 95% CI: −0.43, 0.12, p-value=0.265). Due to the limited number of studies we were not able to perform subgroup analyses among active and passive controls.

Discussion

Results from this preliminary meta-analysis suggest that spinal manipulation reduced migraine days and migraine pain or intensity with an overall small effect size and did not impact migraine disability compared to control interventions.

Subgroup analysis stratified by control group type (active versus passive) showed similar magnitudes of effects as the main analyses. Performing analyses stratified by the type of control group used is important because there is concern that beneficial effects of an “active” intervention, like spinal manipulation, may be due solely to the increased attention given to the intervention group. While use of an “active” control group (for example, sham manipulation or placebo therapy) may help to avoid this potential bias, developing sham manipulations that are non-therapeutic is a challenge. In this meta-analysis, spinal manipulation was associated with significant reductions in migraine days compared to those in active control groups which suggests that the results seen for the intervention group are not solely due to attention or expectation.

Our risk of bias assessment also indicated areas in which some studies received high bias scores (for example random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, pre-specifying a primary outcome, and reporting on compliance). Identifying areas where prior studies have shown limitations may help guide and strengthen the scientific rigor of future research in this field. For example, pre-specifying the primary outcome as well as collecting and reporting on compliance over the course of a study should be implemented in all future trials of spinal manipulation. Blinding of participants in studies of spinal manipulation can be difficult depending upon the type of comparison group used in the trial. Two recent studies used sham therapy for one of their control groups. Both formally evaluated the blinding of participants and observed that it was possible achieve blinding in trials of spinal manipulation.16, 17 Even if participants are unable to be blinded (for example, when spinal manipulation is compared to pharmacological treatment alone), individuals analyzing the data should be blinded to treatment group assignment.

The exact mechanisms by which spinal manipulation may influence migraine days, pain, and disability are not yet known but a few hypotheses have been proposed. Cerritelli et al suggested that spinal manipulation may affect migraine through the rebalance of the vegetative nervous system nuclei or by the reduction of pro-inflammatory substances.16 Chaibi et al. suggested that spinal manipulation may stimulate neural inhibitory systems by activating central descending inhibitory pathways.17

Although the results of this meta-analysis suggest that spinal manipulation may reduce migraine days and migraine pain/intensity, several important limitations should be discussed. Given the variation in study quality and specific study design features, we consider the results of these meta-analyses to be preliminary. Additional well-designed trials are needed before a definitive statement on the use of spinal manipulation for migraine can be made. Unfortunately the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis prohibited us from using meta-regression to formally quantify the effects of different design features on our results. In addition, the populations enrolled in these studies varied. In particular, the study by Cerritelli et al. enrolled a population of chronic migraineurs16, while other studies enrolled participants who experienced as few as 1 migraine per month. The study of chronic migraineurs observed larger effect estimates than any of the other studies included in our meta-analysis.16 Until more studies of both chronic and episodic migraine are performed, we cannot determine if there are differences in the effect of spinal manipulation on chronic versus episodic migraine. Although all studies examined a measure of migraine days, there was often variability in the assessments of migraine pain/intensity or migraine disability. This limited our ability to determine the influence of spinal manipulation on other migraine outcomes. We were also unable to explore the effect of spinal manipulation on different follow-up lengths due to the limited number of studies and assessment time points in each trial. We limited our systematic review and meta-analysis to studies listed in PubMed which would exclude trials that were never published. This may result in publication bias if trials which were not able to be completed or which had null results were not published. A search of clinicialtrials.gov identified two additional ongoing trials (one not yet recruiting and one currently recruiting) which should be included in future systematic reviews of spinal manipulation for migraine. We were unable to formally assess publication bias using a funnel plot due to the low number of studies included in this meta-analysis.

Only two studies explicitly collected adverse events. In order to fully understand the benefits and risks of spinal manipulation for migraineurs, more rigorous assessments of potential adverse events should be performed. Adequate monitoring of adverse events is particularly important in this population because of concerns that cervical manipulation may be associated with cervical artery dissection22 and the increased risk of cervical artery dissection among migraineurs.23, 24 Further understanding of the potential risks and benefits of spinal manipulation for migraineurs may help migraineurs and their physicians determine the best course of care.

Most studies included in this review focused on spinal manipulation techniques. While spinal manipulation is one feature of chiropractic care, physical therapy, and osteopathy, current therapeutic models typically encompass a multimodal approach including but not limited to education, spinal stabilization exercises, soft tissue manipulation, breathing training, stretching techniques, nutrition, and ergonomic modifications.25–27 It is currently unknown whether the wide variety of potential multimodal care models as practiced in clinical settings reduce migraine days, pain, or disability.

Conclusion

Results from this preliminary meta-analysis suggest that spinal manipulation may reduce migraine days and pain/intensity. However, variation in study quality makes it difficult to determine the magnitude of this effect. Methodologically rigorous, large-scale RCTs are warranted to better inform the evidence base for the role of spinal manipulation in integrative models of care provided by chiropractors, physical therapists, and osteopathic physicians as a treatment for migraine.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Results of meta-analysis evaluating spinal manipulation for migraine days.

ES=effect size; SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; SM=spinal manipulation

*Note: These effect estimates exclude the study by Cerritelli et al. Effect estimates including that study can be found in the Supplement.

Figure 3.

Results of meta-analysis evaluating spinal manipulation for migraine pain/intensity.

ES=effect size; SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; SM=spinal manipulation

*Note: These effect estimates exclude the study by Cerritelli et al. Effect estimates including that study can be found in the Supplement.

Figure 4.

Results of meta-analysis evaluating spinal manipulation for migraine disability.

ES=effect size; SE=standard error; CI=confidence interval; SM=spinal manipulation

*Note: These effect estimates exclude the study by Cerritelli et al. Effect estimates including that study can be found in the Supplement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was made possible by a grant from the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, the NCMIC foundation, Inter-Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR) through Palmer College Foundation, and National Institutes of Health grants K24 AT009282 and K01HL128791.

Abbreviations:

- RCTs

randomized clinical trials

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Pamela M. Rist has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Audrey Hernandez has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Carolyn Bernstein has received funding from Amgen.

Matthew Kowalski has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation.

Kamila Osypiuk has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Robert Vining has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Cynthia R. Long has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Christine Goertz has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the Director of the Inter-Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR).

Rhayun Song has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Peter M. Wayne has received funding from the NCMIC Foundation and served as the co-Director of the Inter-Institutional Network for Chiropractic Research (IINCR).

References

- 1.Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Berger ML. Burden of migraine in the United States: disability and economic costs. Archives of internal medicine. 1999;159:813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53:1300–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorlund K, Sun-Edelstein C, Druyts E, et al. Risk of medication overuse headache across classes of treatments for acute migraine. The journal of headache and pain. 2016;17:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells RE, Bertisch SM, Buettner C, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults with migraines/severe headaches. Headache. 2011;51:1087–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, Hurwitz EL, Brook RH. Spinal manipulation for low-back pain. Annals of internal medicine. 1992;117:590–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams J, Lauche R, Peng W, et al. A workforce survey of Australian chiropractic: the profile and practice features of a nationally representative sample of 2,005 chiropractors. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 2017;17:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen MG, Hyland JK, Goertz CM, Kollasch MW. Pratice Analysis of Chiropractic. Colorado: National Board of Chriopractic Examiners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Posadzki P, Ernst E. Spinal manipulations for the treatment of migraine: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2011;31:964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaibi A, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB. Manual therapies for migraine: a systematic review. The journal of headache and pain. 2011;12:127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astin JA, Ernst E. The effectiveness of spinal manipulation for the treatment of headache disorders: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2002;22:617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson CF, Bronfort G, Evans R, Boline P, Goldsmith C, Anderson AV. The efficacy of spinal manipulation, amitriptyline and the combination of both therapies for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1998;21:511–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker GB, Tupling H, Pryor DS. A controlled trial of cervical manipulation of migraine. Australian and New Zealand journal of medicine. 1978;8:589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuchin PJ, Pollard H, Bonello R. A randomized controlled trial of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2000;23:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerritelli F, Ginevri L, Messi G, et al. Clinical effectiveness of osteopathic treatment in chronic migraine: 3-Armed randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2015;23:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaibi A, Benth JS, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB. Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine: a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo, randomized controlled trial. European journal of neurology. 2017;24:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voigt K, Liebnitzky J, Burmeister U, et al. Efficacy of osteopathic manipulative treatment of female patients with migraine: results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2011;17:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J, Green SE. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. In: Higgins J, Green S, eds: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC medical research methodology. 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biller J, Sacco RL, Albuquerque FC, et al. Cervical arterial dissections and association with cervical manipulative therapy: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2014;45:3155–3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Giuli V, Grassi M, Lodigiani C, et al. Association Between Migraine and Cervical Artery Dissection: The Italian Project on Stroke in Young Adults. JAMA neurology. 2017;74:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rist PM, Diener HC, Kurth T, Schurks M. Migraine, migraine aura, and cervical artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2011;31:886–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryans R, Descarreaux M, Duranleau M, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with headache. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2011;34:274–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore CS, Sibbritt DW, Adams J. A critical review of manual therapy use for headache disorders: prevalence, profiles, motivations, communication and self-reported effectiveness. BMC neurology. 2017;17:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nattagh-Eshtivani E, Sani MA, Dahri M, et al. The role of nutrients in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraine headaches: Review. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2018;102:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.