Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF), a most deadly genetic disorder, is caused by mutations of CF transmembrane receptor (CFTR) - a chloride channel present at the surface of epithelial cells. In general, two steps have to be involved in treatment of the disease: correction of cellular defects and potentiation to further increase channel opening. Consequently, a combinatorial simultaneous treatment with two drugs with different mechanisms of action, lumacaftor and ivacaftor, has been recently proposed. While lumacaftor is used to correct p.Phe508del mutation (the loss of phenylalanine at position 508) and increase the amount of cell surface–localized CFTR protein, ivacaftor serves as a CFTR potentiator that increases the open probability of CFTR channels. Since the main organ that is affected by cystic fibrosis is the lung, the delivery of drugs directly to the lungs by inhalation has a potential to enhance the efficacy of the treatment of CF and limit adverse side effects upon healthy tissues and organs. Based on our extensive experience in inhalation delivering of drugs by different nanocarriers, we selected nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) for the delivery both drugs directly to the lungs by inhalation and tested NLC loaded with drugs in vitro (normal and CF human bronchial epithelial cells) and in vivo (homo-zygote/homozygote bi-transgenic mice with CF). The results show that the designed NLCs demonstrated a high drug loading efficiency and were internalized in the cytoplasm of CF cells. It was found that NLC-loaded drugs were able to restore the expression and function of CFTR protein. As a result, the combination of lumacaftor and ivacaftor delivered by lipid nanoparticles directly into the lungs was highly effective in treating lung manifestations of cystic fibrosis.

Keywords: Fibrosis, Pulmonary delivery, Lipid nanoparticles, Imaging, Transgenic mice, Cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR)

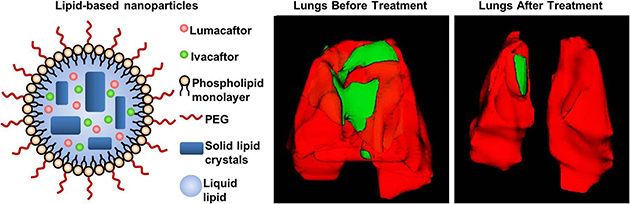

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disorder which is considered to be one of the most common fatal genetic disorders among the Caucasian population [1,2]. Though the life expectancy has been increased in the recent decades, the average survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis remains to be about 40 years. The disease is caused by mutations in the gene of cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR). The CFTR protein is a chloride channel present at the surface of epithelial cells in multiple organs which is responsible for the chloride ions and water transport in and out of the cells. Currently, over 1500 types of CFTR mutations have been discovered [3,4]. Some of these mutations affect the quantity of CFTR at the cell membrane while others affect the function of these CFTR channels [3,5,6]. The most commonly found mutation is delF508 mutation: loss of a phenylalanine at position 508 which is found in at least one allele in the majority of CF patients (approximately 45% of patients are homozygous for this allele). The main organ that is affected by cystic fibrosis is the lung where the mutations in the CFTR results in production of thick, viscus mucus leading to the airways obstruction, infection, inflammation and eventually end-stage lung disease. Different tactics have been explored for treatment of cystic fibrosis [7–9].

One approach to treating cystic fibrosis is based on addressing the fundamental cause of the disease by targeting the CFTR protein dys-function [3]. Two steps have to be involved in this process: correction of cellular defects and potentiation to further increase channel opening. Consequently, it was proposed to use the combination of two therapeutic agents with different mechanisms of action that could be applied simultaneously for the efficient treatment of CF. The first drug is lumacaftor (Luma) - the investigational CFTR corrector that has been shown in vitro to correct p.Phe508del CFTR misprocessing and increase the amount of cell surface–localized protein [2,10]. The second one is ivacaftor (Iva) - an FDA approved CFTR potentiator that increases the open probability of CFTR channels (i.e., the fraction of time that the channels are open) [2,10]. In vitro studies have shown that ivacaftor also potentiates surface-localized p.Phe508del and the combination of lumacaftor with ivacaftor has been associated with a sufficient increase in chloride transport which cannot be achieved by using either agent alone [11]. The dosage form for the existing drug is tablet for the oral use. Currently, there were no attempts made to incorporate Luma and Iva into appropriate nanoparticles for the inhalation delivery. Meanwhile, local delivery of these drugs directly to the lungs may enhance their efficacy and limit possible adverse side effects upon other healthy tissues and organs.

Our group has a broad experience in synthesis of different nano-carriers for the systemic and local administration of therapeutic agents that are currently approved for clinical usage [12–16]. In particular, one of the main areas of interest is treatment of lung diseases by inhalation [17–19]. Recently, we have shown that inhalation treatment using lipid-based nanocarriers loaded with prostaglandin E2 in combination with targeted siRNAs prevented the development of severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice and completely eliminated signs of the disease [20,21]. The key reasons for the successful cure were local delivery of the drugs into the lungs and their encapsulation into the nanocarriers which prevents drugs from fast degradation and elimination from the body and any possible destruction during the inhalation process.

In the present study, we created lipid-based nanocarrier appropriate for the lumacaftor/ivacaftor encapsulation; compared the effecacy of each drug, lumacaftor or ivacaftor, their combination and lipid-based dosage form of these drugs on the correction of the defect in the CFTR protein in vitro; and investigated in vivo the therapeutic efficacy of nanostructured lipid carriers loaded with both drugs and delivered by inhalation to the lungs of genetically modified mice (Cftrtm1Unc Tg (FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J) with cystic fibrosis.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials & Methods

Lumacaftor (VX-809) and Ivacaftor (VX-770) were purchased from Selleckchem via ThermoFisher (Pittsburgh, PA); collagen and bovine serum type1 were obtained from Corning (Bedford, MA), Fibronectin and MQAE dye were purchased from Life Technology (Eugene, OR); SYBR® green PCR master mix was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Warrington, UK); PCR custom primers hQCF3 GACAGTTGTTGGCGG TTGCT (sense) and hQCF4 ACCCTCTGAAGGCTCCAGTTC (Antisense) were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); procirol AT05 (glycerol distearate) GATTEFOSSE, sequalene, and span 85 were purchased from Sigma (Sant-Louis, MO); tween 80 and polyethylene glycol (PEG 2000) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipid Inc., (Alabaster USA).

2.2. Cell culture

16HBE41o- and CFBE41o- cells were kindly provided by Dr. Dieter C. Gruenert (California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, San Francisco, CA). CFBE41o- cells were produced by transformation of bronchial epithelial cells, obtained from a CF patient, with SV40 large T antigen via the replication defective pSVori- plasmid. Cells were grown in fibronectin-coated flasks (25 and 75 cm2 in surface area obtained from Coaster, Corning, Germany) at a density of 2 × 105 cells per cm2 in Minimum Essential Medium w/Earle’s salt (EMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin G), at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Flasks were coated with the fibronectin solution that contains Bovine serum albumin, Collagen I, bovine and Human fibronectin. The culture medium was changed every other day. The passage percentage was 1:10 for one week. Human bronchial epithelial 16HBE14o- cells (used as control for CFBE41o- cells) were cultured as previously reported [22]. Cells were seeded in coated flasks with condition similar to CFBE41o- cells.

2.3. Chloride efflux measurements

CFBE41o − cells were plated with density of 25 × 103 cells/well in a 96 well plate with clear bottom (Coaster®, Corning, Germany) for 24 h [23–25]. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of lumacaftor alone (0.1 μM, 3 μM, 8 μM, 10 μM), ivacaftor alone (0.1 μM, 3 μM, 8 μM, 10 μM), a combination of the both (0.1 μM, 3 μM, 8 μM, 10 μM), and drugs–PEG–NLC (3 μM). After 48 h, all cells were loaded with 10 mM N-(Ethoxycarbonylmethyl)-6-Methoxyquinolinium Bromide (MQAE) for 2 h, then cells were washed with a chloride buffer containing of 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM HEPES, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, and 1 mM MgCl2 pH 7.4, incubated with this buffer for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 followed by exposure to a chloride-free buffer of similar composition (NO3 as the substituting anion). After that, cells were exposed for 10 min to chloride-free buffer containing 100 mM IBMX and 5 mM forskolin (Sigma, Louis, MO). Fluorescence was recorded with a Cary Eclipse Varia spectrofluorometer (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA), using 360 nm (bandwidth 10 nm) as excitation wavelength and 450 nm (bandwidth 10 nm) as emission wavelength. All measurements were done in triplicate using the untreated CFBE41o- cells as a control.

2.4. RNA extraction

CFBE41o- and HBE41o- cell lines were grown on fibronectin-coated flasks. RNA was extracted from confluent cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The concentration and quantity of RNA were assessed using absorbance multi-mode microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland) with the absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm. The A260/A280 ration was between 1.8 and 2.1 indicating a high purity of RNA.

2.5. Gene expression

Gene expression was measured using Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with Ready-To-Go You- Prime First-Strand Beads (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) with 1 μg of total cellular RNA (from 107 cells) and 100 ng of random hexadeoxynucleotide primer (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). After synthesis, the reaction mixture was immediately subjected to qPCR. Three cDNA samples from separate RNA extractions and reverse transcription reactions were used for each cell line. qPCR was performed using SYBER Green Master Mix as detection agent. A fold-change < 1 (control) represented downregulation of the correspondent gene. The fold-change was calculated using the following formula: 2(-ΔCCT). The sequences of primers were: GAPDH ATCGAAATCCCATCACCATCTT (sense), CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG (antisense) and hQCF3 GACAGTTGTTGGCGGTTGCT (sense), ACCCTC TGAAGGCTCCAGTTC (antisense) [26].

2.6. Protein expression

Protein Extraction:

16HBE14o- and CFBE41o- cells grown in fibronectin-coated flasks until confluent, were trypsinzed and after centrifugation (500 g for 5 min), cells were lysed in 55 μL lysis buffer (TRIS 1 mM, NaCl 15 mM, EDTA 0.2 mM, 2% Triton X-100) and protease inhibitor cocktail 1% (Sigma, Louis, MO) then placed on ice for 30 min [27]. After that, the contents were centrifuged for 5 min (14,000 ×g) at 4 °C to remove not soluble materials, and then the pellet was discarded and the supernatant was transferred to other tubes. The protein concentration was quantified by the Bradford method [28].

Western Blotting:

An aliquot of 25 μg of protein was diluted in Laemmli buffer (Sigma, Louis, MO) and separated by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (7.5% acryl amide) mini-protean® TGXTM (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) [27,29]. The separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene membrane (0.45um pore size). A tank blot aperture (Mini Trans-Blot® Electro-phoretic Transfer Cell; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to transfer proteins to a PVD membrane at 25 V on ice overnight. Next day, blocking of nonspecific binding sites were done for 2 h with 5% nonfat dry milk in Trisbuffered saline-Tween (TBST: 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4; 0.1% Tween 20; 140 mM NaCl) at room temperature. A monoclonal mouse anti-human and murine CFTR primary antibody PierceTM (CF3) Thermoscientific Fischer (Waltham, MA), diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST was used to detect the CFTR at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST 2–3 times, the membrane was incubated with the affinity purified goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Dianova, Germany) diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST 1:10 000 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the membrane again with SigmaFast NBT (nitro blue tetrazolium) and BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate) Sigma, Chemical Co., (St. Louis, MO) were used for detection. ImageJ version 1.41 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was applied for densitometry evaluation of the intensity of the CFTR bands. Further, protein extract from non-treated CFBE41o–cells and 16HBE14o– cells were used as control. To assure comparable protein amount and expression, anti-α-tubulin mouse IgG1 monoclonal (Tubulin alpha) Life Technologies (Eugene, OR) use for normalization of the Western blot data.

2.7. Preparation and drug loading of nanostructured lipid carriers

The PEGylated drugs–PEG–NLCs were prepared by emulsion-evaporation and low temperature-solidification method [13,30]. The lipid and aqueous phases were prepared separately. The aqueous phase consists of 65 mg tween80, 150 mg span 85, 30 mg DSPE PEG, 75 mg span 80 and 7 mL of deionized water. The lipid phase consists of 50 mg squalene, 50 mg Procirol, 100 μL of lumacaftor (25 mg/mL), 100 μL of ivacaftor (25 mg/mL) and 800 μL ethanol. After that, both aqueous and lipid phase were allowed to warm up at 67 °C for 30 min on dry bath get the homogeneous emulsion. The homogenization of particles was done using Bio-Gen pro200 (Proscientific, USA). During this process, the lipid phase has been added to the aqueous phase. This homogenization step continued for 5 min at 9000 rpm followed by 5 min at 12000 rpm. After that, the hot pre-emulsion was pulse sonicated for 10 min with 50% amplitude using Fisher Scientific™ Model 120 Sonic Dismembrator. Then the emulsion was cooled on ice bath for 90 min, and the dispersion of drugs–PEG–NLC was obtained. A schematic structure of drug loaded PEGylated NLC is presented on (Fig. 1).

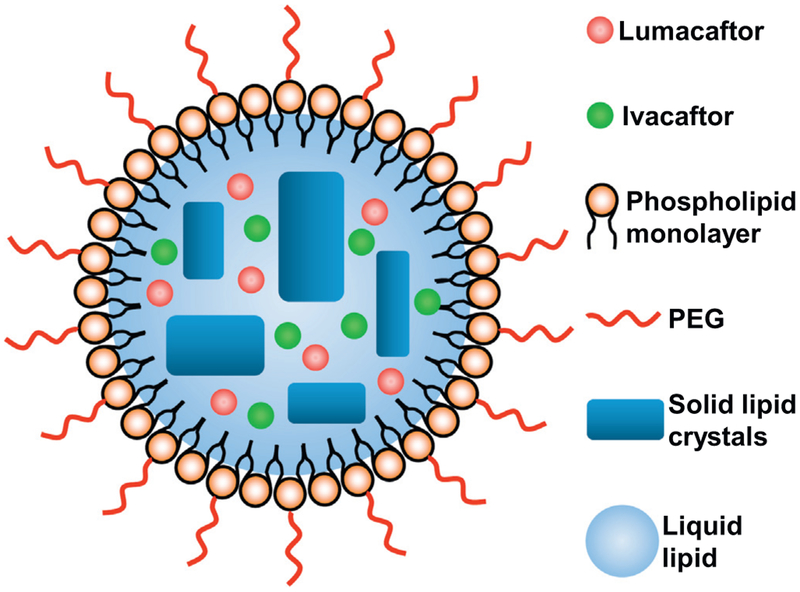

Fig. 1.

Drug loaded PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) composed of solid lipid matrix crystals immersed in liquid lipid droplets and covered with phospholipid monolayer.

2.8. Particle size and zeta potential

The particle size distribution and charge (zeta potential) were measured using Malvern ZetaSizer NanoSeries (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All measurements were carried out at room temperature. Each parameter was measured three times for each batch, average values and standard deviations were calculated as previously described [13,20].

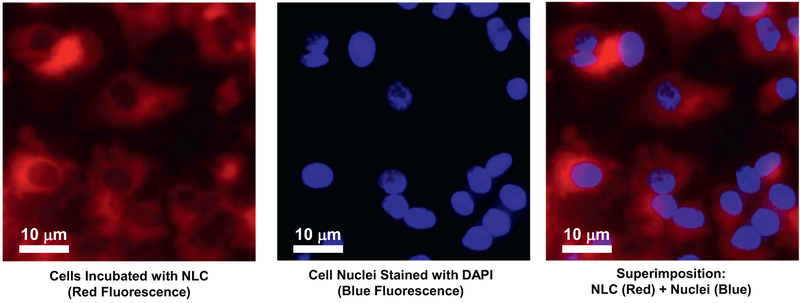

2.9. Cellular uptake and localization of NLC

Cellular internalization of NLC was monitored using fluorescence microscopy. CFBE41o– cells were incubated with Rhodamine labeled nanocarriers for 24 h followed by further nuclear staining with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All images were captured using an Olympus IX170 inverted epifluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY).

2.10. Entrapment efficacy and drug loading

The drug loading capacity and entrapment efficiency of the NLC formulation was assessed by measuring the amount of the un-entrapped drug by using Amicon ultra centrifugal filter units (Sigma–Aldrich Ultra-15, MWCO 10 KDa) quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Water Corporation, Milford, MA). The chromatographic apparatus consisted of a Model 1525 pump (Waters Instruments, Milford, MA), a Model 717 Plus auto-injector (Waters Instruments, Milford, MA) and a Model 2487 variable wavelength UV detector (Waters Instruments, Milford, MA) connected to the Millennium software [31].

Briefly, 1 mL of the NLC formulation was diluted with 2 mL of diluents to allow the un-loaded drug particles to dissolve. The diluted sample was kept in the upper compartment of the ultra-centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 min. The free drug in the aqueous phase moves through the semi permeable filter membrane to the lower chamber, whereas the drugs entrapped within the nanoparticle retained in the upper chamber. The flow through in the lower chamber was measured by HPLC using auto sampler, dual wavelength absorbance detector with wavelength set to 229nm. A column with 125mm 4mm Lichrosphere 100 RP-18 was obtained from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ), used to identify and quantify the concentration of lumacaftor and ivacaftor. The mobile phase was composed of 1:1 ratio of acetonitrile DDW eluted isocratically throughout the measurement. Samples were dissolved in acetonitrile before injection into a 20L sample loop. Drug incorporation efficiency in this study was representing by the retention of both drugs in the filtered NLC with respect to the originally added drugs. The retention times of lumacaftor and ivacaftor were 4.43 and 4.56 min respectively. The flow rate was kept at 0.5mL/min. The NLC were lyophilized and stored at 4 °C for further shelf stability test. The entrapment efficiency and drug loading was calculated by the following equations:

where the EE%: entrapment efficiency, DL%: drug loading, w1 = amount of drug added in the NLC, w2 = amount of un-entrapped drug, w3 = amount of the lipids added.

2.11. Animals

Cftrtm1Unc Tg(FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J homozygote/homozygote bitransgenic mice 6–8 weeks old were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) [32]. These mice with mixed genetic background consisting of C57BL/6, FVB/N and 129, are knock-outs for the murine CFTR gene, but express human CFTR in the gut under control of the FABP1 (fatty acid binding protein1) promoter, which prevents acute intestinal obstruction 1 [32,33]. All mice were maintained in micro isolated cages under pathogen free conditions in the animal maintenance facilities of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Veterinary care followed the guidelines described in the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (AAALAC) as well as the requirements established by the animal protocol approved by the Rutgers Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.12. Inhalation exposure system and treatment

A one-jet Collison nebulizer (BGI Inc., Waltham, MA) operated at an aerosolization flow rate of 2 L/min using dry and purified air (Airgas East, Salem, NH) was used to aerosolize particles while an additional air flow of 2–3 L/min was introduced to dilute and desiccate the resulting aerosol according to the previously described procedure [15,20,34]. Briefly, the Collison nebulizer was equipped with a precious fluid cup to minimize the amount of liquid needed for reliable aerosolization. Then, under slight positive pressure, the entire aerosol flow of 4–5 L/min entered a mixing box of the 5-port exposure chamber (CH Technologies, Westwood, NJ) and was distributed to each animal containment tube via round pipes (four out of five chambers were used in the experiments). Each containment tube was connected to the distribution chamber via a connector cone, which features a spout in its middle to deliver fresh aerosol to a test animal and round openings in its back for exhaled air. During the inhalation experiments, tested animals were positioned in a containment tube so that the animal’s nose was at the spout, or “inhalation point”. The animals were held in place by a plunger. The air exhaled by the test animals escapes the connector cone via openings in the cone’s back and was exhausted. Mice (eight mice per group) were treated twice per week by inhalation with NLC containing lumacaftor and ivacaftor within 4 weeks.

2.13. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT)

Mice were MRI-scanned using Fast Spin Echo (T2) and Gradient Echo (T1) sequences. Both scans utilized 16 slices at 1.5 mm thickness with a field of view of 100 mm. Scans were combined in the analysis software, reviewed and segmented.

Mice were CT-scanned using high current (400 mA) and high voltage (45 kV) with a “High Resolution” file size. Lungs were digitally isolated from the image using a CT-ROI (−999 to 10) and then segmented into four components based on voxel intensity, which generally represents tissue radio-density. Volumes of each component were than determined.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using appropriate a paired Student’s t-test or single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), and shown as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The difference between variants was considered significant if P < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Fluorescence measurements of chloride efflux

CFBE41o- cells were incubated with Luma (VX-809), Iva (VX-770) Luma-Iva combination, and Luma-Iva–NLC for 48 h, and chloride efflux was measured as a relative change in fluorescence (Frelative Fluorescence) of the chloride-sensitive dye MQAE N-(ethoxycarbonylmethyl)-6-methoxyquino-linium bromide as follows:

where, F denotes measured fluorescence value and F0 – a level of fluorescence in the untreated cells (control).

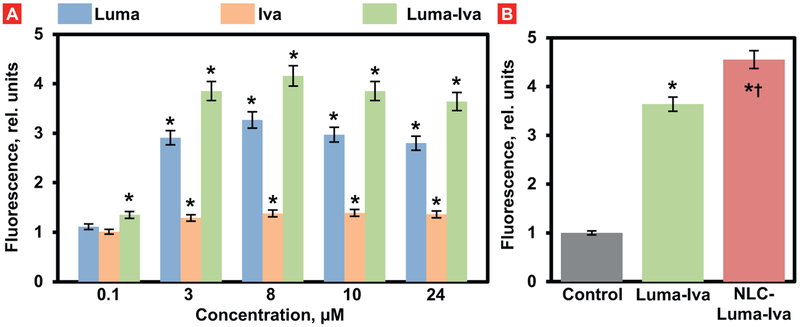

Cells treated with Luma (3 μM) showed an increase in chloride ef-flux when compared with control (Fig. 2A, P < .05). Further increase in drug concentration (8 μM) resulted in a higher chloride efflux when compared with control). The cells treated with Iva (3 μM, and 8 μM) showed a slight increase in chloride transport throughout the cell membrane when compared with cells treated with Luma (P < .05). The highest chloride efflux has been found in cells treated with both drugs at concentrations 3 μM, and 8 μM. Further increase in drug concentrations (≥ 10 μM) did not to the significant increase in the chloride transport. Cells treated with drugs delivered by NLC (3 μM), showed slight improvement in the chloride efflux when compared with the free non-bound Luma-Iva combination (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Chloride efflux from cystic fibrosis (CF) human bronchial epithelial CFBE41o- cells after treatment with free and NLC-bound lumacaftor (Luma), ivacaftor (Iva) and their combination. A–Different concentrations of free non-bound drugs; B – Combination of free non-bound and encapsulated into NLC Luma and Iva drugs. The ordinate shows the relative fluorescence of MQAE dye. Fluorescence in untreated CF cells was set to 1 unit. Mean ± SD are shown. *P < .05 when compared with untreated CF cells. †P < .05 when compared with the combination of free drugs.

3.2. Analysis of CFTR mRNA expression by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-QPCR)

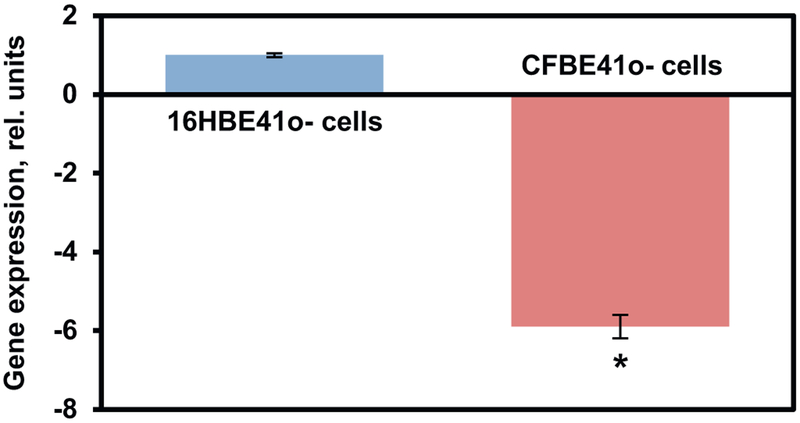

RT- PCR was used to analyze the expression of mRNA in both 16HBE14o– and CFBE41o- cell lines. The 16HBE14o– CFTR expression value was defined as 1 and the CFBE41o- CFTR expression then was normalized to this value. CFTR mRNA levels of the CFBE41o- cells were expressed as a fold change relative to native CFTR mRNA 16HBE14o–cells (Fig. 3). A significantly lower (almost 6 fold) expression of wild type CFTR mRNA was observed in CFBE41o- cells when compared with normal 16HBE14o– cells (P < .05).

Fig. 3.

The relative expression of the CFTR gene in human bronchial epithelial 16HBE14o- (healthy) and CFBE41o- (CF) cells. The expression in 16HBE14o-cells was set to 1 unit. Means ± SD are shown. *P < .05 when compared with 16HBE14o- cells.

3.3. Analysis of CFTR protein expression by western blotting

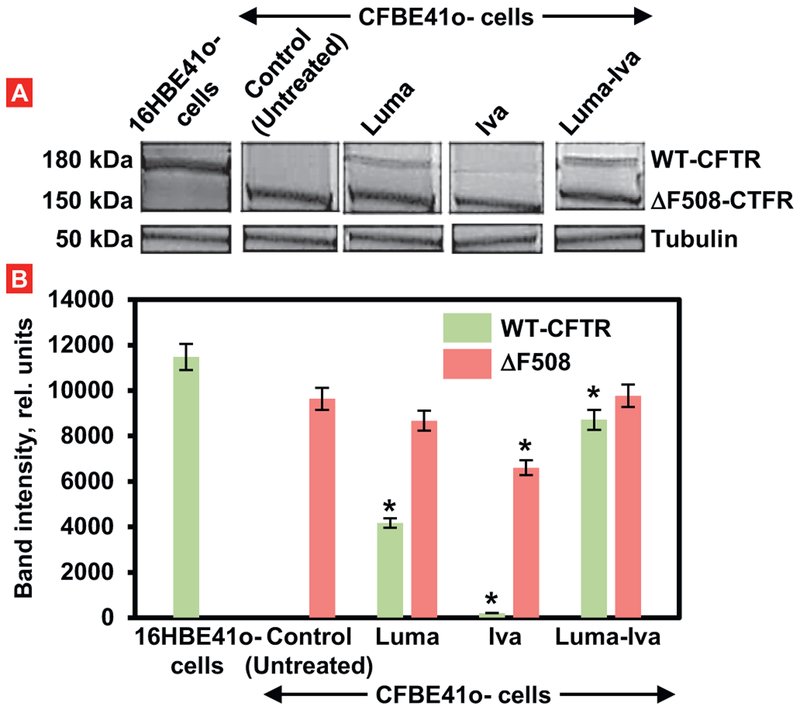

Results from immunoblot of normal cells (16HBE41o-) showed an intense band of wild type CFTR protein (WT-CFTR) with molecular weight about 180 kDa (Fig. 4). The immunoblot for CFBE41o- cells expressing ΔF508-CFTR showed less intense band of mutated protein with a molecular weight 150 kDa. Treatment of CFBE41o- cells with Luma alone led to the reappearing of a mature form of CFTR protein (WT-CFTR). However, its expression was substantially less pronounced when compared with control cells (Fig. 4). In contrast, CFBE41o- cells treated with Iva alone still did not express a mature form of the tested protein and showed only its immature form. Treatment of cells with both drugs significantly increased the expression of the mature form of the protein and almost not influenced on its mutated form.

Fig. 4.

Expression of CFTR protein (Western blotting) in healthy (16HBE41o-) and CF (CFBE41o-) human bronchial cells. Two types of proteins: a mature wild type form of CFTR (WT-CFTR, 150 kDa) and mutated (ΔF508-CFTR, 150 kDa) were investigated using tubulin (50 kDa) as an internal standard. CFBE41o-cells were treated for 48 h with 3 μM of free lumacaftor (Luma), ivacaftor (Iva) and their combination. A – typical Western blot image. B – Quantitation of protein expression (Means ± SD are shown). *P < .05 when compared with the expression of corresponding type of protein in untreated CFBE41o- cells.

3.4. NLC characterization and cellular internalization

The average particle size of drugs–PEG–NLC was 128.04 ± 1.58 nm and zeta potential was −46.5 ± 8.05 mV. The entrapment of lumacaftor and ivacaftor within the PEG-NLC was quantified using HPLC. Developed formulation was able to entrap 10 mg of drugs used in the synthesis yielding an entrapment efficiency of 100%. It was found that 24 h after incubation of CFBE41o- cells with NLC, the particles were successfully internalized and accumulated predominately in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative images of human bronchial epithelial CFBE41o- cells incubated within 24 h with NLC (red fluorescence). Cell nuclei were stained with nuclear-specific dye (DAPI, blue fluorescence). Superimposition of images allows for detecting of cytoplasmic localization of NLC. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

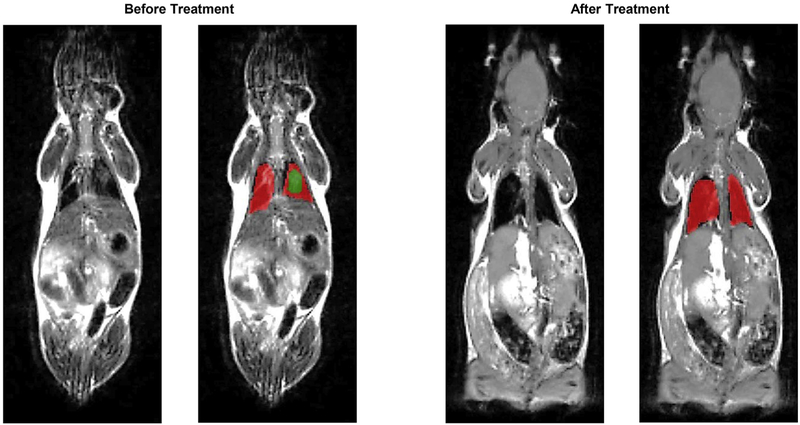

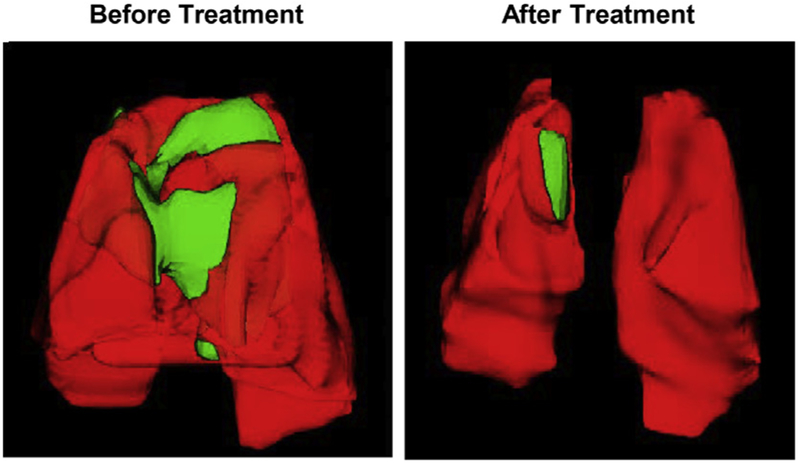

3.5. Lung assessment before and after inhalation treatment of mice with cystic fibrosis

Mice were treated twice a week during four weeks by inhalation with NLC containing both drugs lumacaftor and ivacaftor. Prior to the beginning of the treatment all mice were evaluated for the presence of cystic fibrosis lesions in their lungs using MRI and CT scan. Both methods revealed the presence of the regions usually associated with fibrosis and edema (Figs. 6 and 7). Though, the level of lung damage differed for all experimental mice. The volumes of the affected regions in the mice lungs are presented in Table 1. Based on the MRI and CT scan results at the end of the treatment, the affected regions in mice lungs became much smaller or totally disappeared (Figs. 6, 7 and Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Representative magnetic resonance images (MRI) of Tg(FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J homozygote/homozygote bi-transgenic mice with cystic fibrosis before and after treatment. Mice were treated twice per week within four weeks by inhalation with nanostructured lipid carriers containing lumacaftor and ivacaftor. Normal lung tissues are colored in red, while fibrotic tissues – in green. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 7.

Representative computer tomography (CT) images of lungs of Tg(FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J homozygote/homozygote bi-transgenic mice with cystic fibrosis before and after treatment. Mice were treated twice per week within four weeks by inhalation with nanostructured lipid carriers containing lumacaftor and ivacaftor. Normal lung tissues are colored in red, while fibrotic tissues – in green. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Volumes of fibrotic tissues in lungs of Tg(FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J homozygote/homozygote bi-transgenic mice before and after treatment. Mice were treated twice per week within four weeks by inhalation with nanostructured lipid carriers containing lumacaftor and ivacaftor. Means ± SD are shown.

| Tissues | Untreated animals (mm3) | Treated animals (mm3) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung volume | 363 ± 92 | 335 ± 103 |

| Volume of fibrotic tissues | 183 ± 55 | 9 ± 39* |

P < .05 when compared with non-treated animals.

4. Discussion

Present study was aimed at verifying the concept that two drugs lumicaftor and invocator approved for the cure of cystic fibrosis could be encapsulated into nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) designed for the inhalation delivery to lungs. Currently, both drugs are used for oral administration. Lumicaftor is CFTR corrector and is defined as an agent that corrects a processing defect of class II mutations, such as F508del, therefore promises to be appropriate for the majority of cystic fibrosis patients [2]. Ivacaftor is CFTR potentiator and is defined as agent that potentiate mutated but apically localized CFTR and may therefore be of therapeutic value for class III and IV mutations [2]. Proposed NLC represented a new generation of lipid nanoparticles, which were created using the combination of the benefits from other drug carriers used not only by our group but also by other scientific groups. The drugs–PEG–NLCs were prepared by emulsion-evaporation and low temperature-solidification method which allows incorporating low water soluble drugs into the lipid phase.

The effect of each drug alone and their encapsulated form on the CFRT protein expression and function in vitro was conducted on CFBE41o cell line generated by transformation of CF tracheo-bronchial cells. Incorporation into nanocarriers not only improves cellular penetration of drugs but also enhances their combination effect on intracellular processes most likely due to their similar pharmacokinetic properties. This fact was confirmed by measurement of chloride efflux in CFBE41o cells. The data showed that cells treated with drugs–PEG–NLC have demonstrated the improvement in ion transport with 3 μM concentration compared to drugs combination with same concentration. Partly this effect could be explained by the ability of PEG-NLC to penetrate the mucus, and enhance drug delivery through the cell membrane of CFBE41o- bronchial epithelial cells. In addition, NLC synthesized for this study could potentially be exploited as a carrier with improved drug loading capacity and controlled drug release properties.

In the second part of the study (in vivo) designed NLC loaded with both drugs lumicaftor and ivacaftor were administered to mice by inhalation method using collision nebulizer. The treatment was applied on Cftrtm1Unc Tg(FABPCFTR)1Jaw/J homozygote/homozygote bitransgenic mice. The results of study showed that the nanocarrier-delivered drugs combination successfully treated lung cystic fibrosis.

5. Conclusions

Co-delivery of two drugs with different mechanisms of action, lumacaftor and ivacaftor, encapsulated into the lipid-based nanoparticles and delivered by inhalation directly to the lungs demonstrated a high effectiveness in treating lung manifestations of cystic fibrosis. In vivo data provided a proof-of-concept of the underlining hypothesis and showed an extraordinary potential of the combinatorial local simultaneous lung delivery of both drugs by lipid nanoparticles for treatment of cystic fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (R01 HL118312 and CA209818) and Busch Biomedical Research Grant. We thank Dr. E. Yurkow and Mr. D. Adler from Rutgers Molecular Imaging Center for the assistance with obtaining and analyzing the imaging data. We also are grateful to Dr. Dieter C. Gruenert (California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, San Francisco, CA) for kindly providing 16HBE41o- and CFBE41o- cells.

References

- [1].Hafen G, Hurst C, Yearwood J, Smith J, Dzalilov Z, Robinson P, A new scoring system in Cystic Fibrosis: statistical tools for database analysis – a preliminary report, BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak 8 (2008) 44, 10.1186/1472-6947-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Griesenbach U, Alton E, Recent advances in understanding and managing cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator dysfunction, F1000Prime Rep. 7 (2015), 10.12703/p7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Welsh MJ, Smith AE, Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dys-function in cystic fibrosis, Cell 73 (1993) 1251–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sohma Y, Yu YC, Hwang TC, Curcumin and genistein: the combined effects on disease-associated CFTR mutants and their clinical implications, Curr. Pharm. Des 19 (2013) 3521–3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sorio C, Montresor A, Bolomini-Vittori M, Caldrer S, Rossi B, Dusi S, Angiari S, Johansson JE, Vezzalini M, Leal T, Calcaterra E, Assael BM, Melotti P, Laudanna C, Mutations of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene cause a monocyte-selective adhesion deficiency, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 193 (2016) 1123–1133, 10.1164/rccm.201510-1922OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baker MW, Atkins AE, Cordovado SK, Hendrix M, Earley MC, Farrell PM, Improving newborn screening for cystic fibrosis using next-generation sequencing technology: a technical feasibility study, Genet. Med 18 (2016) 231–238, 10.1038/gim.2014.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Villate-Beitia I, Zarate J, Puras G, Pedraz JL, Gene delivery to the lungs: pulmonary gene therapy for cystic fibrosis, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm (2017) 1–11, 10.1080/03639045.2017.1298122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bellec J, Bacchetta M, Losa D, Anegon I, Chanson M, Nguyen TH, CFTR inactivation by lentiviral vector-mediated RNA interference and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in human airway epithelial cells, Curr. Gene Ther 15 (2015) 447–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morgan WJ, Wagener JS, Pasta DJ, Millar SJ, VanDevanter DR, Relationship of Antibiotic Treatment to Recovery after Acute FEV1 Decline in Children with Cystic Fibrosis, (2017), 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201608-615OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hubert D, Chiron R, Camara B, Grenet D, Prevotat A, Bassinet L, Dominique S, Rault G, Macey J, Honore I, Kanaan R, Leroy S, Desmazes Dufeu N, Burgel PR, Real-life initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination in adults with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the Phe508del CFTR mutation and severe lung disease, J. Cyst. Fibros (2017), 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Popowicz N, Wood J, Tai A, Morey S, Mulrennan S, Immediate effects of lumacaftor/ivacaftor administration on lung function in patients with severe cystic fibrosis lung disease, J. Cyst. Fibros (2017), 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garbuzenko OB, Mainelis G, Taratula O, Minko T, Inhalation treatment of lung cancer: the influence of composition, size and shape of nanocarriers on their lung accumulation and retention, Cancer Biol. Med 11 (2014) 44–55, 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Taratula O, Kuzmov A, Shah M, Garbuzenko OB, Minko T, Nanostructured lipid carriers as multifunctional nanomedicine platform for pulmonary co-delivery of anticancer drugs and siRNA, J. Control. Release 171 (2013) 349–357, 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang M, Garbuzenko OB, Reuhl KR, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Minko T, Two-inone: combined targeted chemo and gene therapy for tumor suppression and prevention of metastases, Nanomedicine (Lond) 7 (2012) 185–197, 10.2217/nnm.11.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Garbuzenko OB, Saad M, Pozharov VP, Reuhl KR, Mainelis G, Minko T, Inhibition of lung tumor growth by complex pulmonary delivery of drugs with oligonucleotides as suppressors of cellular resistance, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107 (2010) 10737–10742, 10.1073/pnas.1004604107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Savla R, Minko T, Nanotechnology approaches for inhalation treatment of fibrosis, J. Drug Target 21 (2013) 914–925, 10.3109/1061186X.2013.829078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Garbuzenko OB, Saad M, Betigeri S, Zhang M, Vetcher AA, Soldatenkov VA, Reimer DC, Pozharov VP, Minko T, Intratracheal versus intravenous liposomal delivery of siRNA, antisense oligonucleotides and anticancer drug, Pharm. Res 26 (2009) 382–394, 10.1007/s11095-008-9755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Savla R, Garbuzenko OB, Chen S, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Minko T, Tumor-targeted responsive nanoparticle-based systems for magnetic resonance imaging and therapy, Pharm. Res 31 (2014) 3487–3502, 10.1007/s11095-014-1436-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garbuzenko OB, Winkler J, Tomassone MS, Minko T, Biodegradable Janus nanoparticles for local pulmonary delivery of hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules to the lungs, Langmuir 30 (2014) 12941–12949, 10.1021/la502144z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garbuzenko OB, Ivanova V, Kholodovych V, Reimer DC, Reuhl KR, Yurkow E, Adler D, Minko T, Combinatorial treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis using nanoparticles with prostaglandin E and siRNA(s), Nanomedicine 13 (2017) 1983–1992, 10.1016/j.nano.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ivanova V, Garbuzenko OB, Reuhl KR, Reimer DC, Pozharov VP, Minko T, Inhalation treatment of pulmonary fibrosis by liposomal prostaglandin E2, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 84 (2013) 335–344, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ehrhardt C, Collnot EM, Baldes C, Becker U, Laue M, Kim KJ, Lehr CM, Towards an in vitro model of cystic fibrosis small airway epithelium: character-isation of the human bronchial epithelial cell line CFBE41o, Cell Tissue Res. 323 (2006) 405–415, 10.1007/s00441-005-0062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Servetnyk Z, Jiang S, Hjelte L, Gaston B, Roomans GM, Dragomir A, The effect of S-nitrosoglutathione and L-cysteine on chloride efflux from cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells, Exp. Mol. Pathol 90 (2011) 79–83, 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dragomir A, Roomans GM, Increased chloride efflux in colchicine-resistant airway epithelial cell lines, Biochem. Pharmacol 68 (2004) 253–261, 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Favia M, Guerra L, Fanelli T, Cardone RA, Monterisi S, Di Sole F, Castellani S, Chen M, Seidler U, Reshkin SJ, Conese M, Casavola V, Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor 1 overexpression-dependent increase of cytoskeleton organization is fundamental in the rescue of F508del cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in human airway CFBE41o- cells, Mol. Biol. Cell 21 (2010) 73–86, 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bebok Z, Collawn JF, Wakefield J, Parker W, Li Y, Varga K, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP, Failure of cAMP agonists to activate rescued deltaF508 CFTR in CFBE41o- airway epithelial monolayers, J. Physiol 569 (2005) 601–615, 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bangel-Ruland N, Tomczak K, Fernandez Fernandez E, Leier G, Leciejewski B, Rudolph C, Rosenecker J, Weber WM, Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-mRNA delivery: a novel alternative for cystic fibrosis gene therapy, J. Gene Med 15 (2013) 414–426, 10.1002/jgm.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chen W, Liang J, He Z, Jiang W, Preliminary study on total protein extraction methods from Enterococcus faecalis biofilm, Genet. Mol. Res 15 (2016), 10.4238/gmr.15038988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cholon DM, Quinney NL, Fulcher ML, Esther CR Jr., Das J, Dokholyan NV, Randell SH, Boucher RC, Gentzsch M, Potentiator ivacaftor abrogates pharmacological correction of DeltaF508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis, Sci. Transl. Med 6 (2014) 246ra296, 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang L, Luo Q, Lin T, Li R, Zhu T, Zhou K, Ji Z, Song J, Jia B, Zhang C, Chen W, Zhu G, PEGylated nanostructured lipid carriers (PEG-NLC) as a novel drug delivery system for biochanin A, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 41 (2015) 1204–1212, 10.3109/03639045.2014.938082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Saad M, Garbuzenko OB, Minko T, Co-delivery of siRNA and an anticancer drug for treatment of multidrug-resistant cancer, Nanomedicine (Lond) 3 (2008) 761–776, 10.2217/17435889.3.6.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhou L, Dey CR, Wert SE, DuVall MD, Frizzell RA, Whitsett JA, Correction of lethal intestinal defect in a mouse model of cystic fibrosis by human CFTR, Science 266 (1994) 1705–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Haston CK, McKerlie C, Newbigging S, Corey M, Rozmahel R, Tsui LC, Detection of modifier loci influencing the lung phenotype of cystic fibrosis knockout mice, Mamm. Genome 13 (2002) 605–613, 10.1007/s00335-002-2190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mainelis G, Seshadri S, Garbuzenko OB, Han T, Wang Z, Minko T, Characterization and application of a nose-only exposure chamber for inhalation delivery of liposomal drugs and nucleic acids to mice, J. Aerosol. Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv 26 (2013) 345–354, 10.1089/jamp.2011-0966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]