Abstract

Investigations of small molecule copper-dioxygen chemistry can and have provided fundamental insights into enzymatic processes (e.g., copper metalloenzyme dioxygen binding geometries and their associated spectroscopy and substrate reactivity). Strategically designing copper-binding ligands has allowed for insight into properties that favor specific (di)copper-dioxygen species. Herein, the tetradentate tripodal TMPA-based ligand (TMPA = tris((2-pyridyl)methyl)amine) possessing a methoxy moiety in the 6-pyridyl position on one arm (OCH3TMPA) was investigated. This system allows for a trigonal bipyramidal copper(II) geometry as shown by the UV-vis and EPR spectra of the cupric complex [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2. Cyclic voltammetry experiments determined the reduction potential of this copper(II) species to be −0.35 V vs. Fc+/0 in acetonitrile, similar to other TMPA-derivatives bearing sterically bulky 6-pyridyl substituents. The copper-dioxygen reactivity is also analogous to these TMPA-derivatives, affording a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex, [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, upon oxygenation of the copper(I) complex [(OCH3TMPA)CuI](B(C6F5)4) at cryogenic temperatures in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran. This highly reactive intermediate is capable of oxidizing phenolic substrates through a net hydrogen atom abstraction. However, after bubbling of the precursor copper(I) complex with dioxygen at very low temperatures (−135 °C), a cupric superoxide species, [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+, is initially formed before slowly converting to [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+. This appears to be the first instance of the direct conversion of a cupric superoxide to a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) species in copper(I)-dioxygen chemistry.

Keywords: cupric superoxide, dioxygen activation, bis-μ-oxo, copper

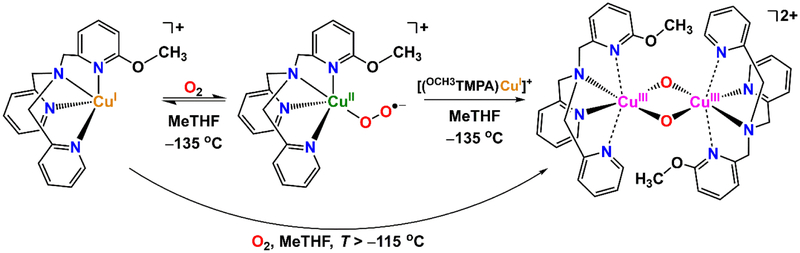

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The reaction of copper(I) with dioxygen is of key importance in catalytic and enzymatic processes. For instance, copper-containing metalloenzymes such as peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM) and dopamine β-hydroxylating monooxygenase (DβM) reductively activate dioxygen, forming a cupric superoxide species (CuII-O2•−) to hydroxylate organic substrates during pro-hormone and neurotransmitter biosynthesis [1–3]. Copper-catalyzed organic reactions cover a wide range of transformations [4], including alcohol oxidation and hydroxylation of C–H containing substrates (one important example being the conversion of methane to methanol) [5–7]. Insight from synthetic model complexes has expanded the scope of copper-dioxygen chemistry and allowed for direct and thorough examination into the nature of various (di)copper-dioxygen adducts, including their oxidizing capabilities [8,9]. These approaches are commonly carried out in organic solvents at cryogenic temperatures in order to stabilize these reactive intermediates.

Initial oxygenation of cuprous complexes may result in the formation of a cupric superoxide complex binding in either an end-on or side-on geometry (ES or SS, respectively, Scheme 1) [1,8,9]. Although these intermediates are not always observed, due to their instability, they are often implicated. Further reaction of a cupric superoxide with a second equivalent of copper(I) results in various dicopper-dioxygen adducts that have been reported to be in equilibrium with each other in many cases [8–11]. These species can be peroxodicopper(II) (binding trans-μ−1,2 or μ-η2: η2 to the copper ions, TP or SP, respectively, Scheme 1) or a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) entity (O, Scheme 1) [8,9].

Scheme 1.

Bubbling dioxygen into a copper(I) solution results in the formation of different CunO2 (n = 1 or 2) isomers, dependent on a variety of factors. The conversions shown with black solid arrows have been previously demonstrated. The new conversion (ES to O, blue dashed arrow) is reported herein for the first time.

Copper complexes bearing TMPA-derivatized ligands (TMPA = tris((2-pyridyl)methyl)amine) have been extensively studied. In particular, copper-dioxygen chemistry has greatly benefited from thoughtfully targeted ligand modifications, incorporating electron-donating, H-bonding, or steric moieties on the pyridyl donors to examine electronic and structural influences on reactivity [12–20]. Studies have shown that functionalizing the 6-pyridyl position of TMPA can significantly alter the observed copper-dioxygen reactivity, resulting in the formation of different dicopperdioxygen intermediates [18].

Herein, novel copper complexes employing a TMPA-based ligand with a methoxy group in the 6-pyridyl position (OCH3TMPA, Scheme 2) were synthesized and their fundamental properties and/or reactivity with O2 were investigated. The cupric complex [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 was synthesized to examine its electrochemical behavior (i.e., its CuII/I E° value) through cyclic voltammetry (CV) and geometry preferences (trigonal bipyramidal vs. square pyramidal) enforced by this methoxy ligand system. A copper(I) dioxygen (CuI/O2) study of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]BArF (BArF = B(C6F5)4−) is also explored at cryogenic temperatures in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF) as solvent. At higher temperatures (i.e., greater than −115 °C), a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex is generated upon oxygenation of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+, formulated as [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, although this intermediate is only stable up to −110 °C (Scheme 2). This copper-dioxygen reactivity is in line with other TMPA-derivatives containing sterically encumbered 6-pyridyl substituents, presumably due to the elongation of that Cu-Npyridine bond, changing the ligand to pseudo-tridentate. However, if dioxygen is introduced at very low temperatures (−135 °C) in MeTHF, the initially observed species is a cupric superoxide species, [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+, which then slowly converts to [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ (Scheme 2). This is the first report of the direct conversion of a cupric superoxide to a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) intermediate (Scheme 1, blue-dashed line).

Scheme 2.

Low-temperature oxygenation of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ results in the initial formation of a cupric superoxide species, which then slowly converts to a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex. The latter forms directly if oxygenation is carried out at temperatures greater than ~ −115 °C. See text.

2. Experimental

2.1. Methods and materials

All chemical reagents and solvents were of commercially available quality and used without further purification unless otherwise specified. OCH3TMPA was synthesized according to a literature procedure [21]. Inhibitor-free tetrahydrofuran (THF) and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF) were distilled over Na/benzophenone under Ar. Pentane was distilled over calcium hydride under Ar. Directly after distillation, THF, MeTHF, and pentane were all deoxygenated by bubbling with Ar for 45 minutes before use. All substrates were purified according to published procedures [22]. Air-free manipulations were performed using Schlenk techniques or a Vacuum Atmospheres OMNI-LAB glovebox. Low temperature UV-Vis spectroscopy experiments were carried out on a Cary Bio-50 spectrophotometer equipped with an Unisoku USP-203A cryostat using a 1 cm modified Schlenk cuvette [23]. Electrochemical experiments were performed using a BAS 100B electrochemical analyzer referenced to the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple in acetonitrile. 1H-NMR spectra were collected using a Bruker Advance 400 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer at 25 °C. All chemical shift values are assigned relative to residual solvent. EPR spectra were collected with an ER 073 magnet equipped with a Bruker ER041 X-Band microwave bridge and a Bruker EMX 081 power supply: microwave frequency = 9.42 GHz, microwave power = 0.201 mW, attenuation = 30 db, modulation amplitude = 10 G, modulation frequency = 100 kHz, temperature = 64 K (liquid nitrogen along with a He gas flow used to cool the EPR cavity). Infrared spectra were collected on a ThermoNicolet Nexus 670 FTIR spectrometer. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) data were obtained using a Finnigan LCQ Duo ion-trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA), a heated capillary temperature of 250 °C and a spray voltage of 5 kV. Gas chromatography data was obtained using an Agilent 6850 gas chromatograph fitted with a DB-5 5% phenylmethyl siloxane capillary column and equipped with a flame-ionization detector (FID). The GC-FID response factor for 3,3’,5,5’-tetra-tert-butyl-(1,1’-biphenyl)-2,2’-diol was compared versus dodecane as the internal standard. Elemental analyses were performed by Micro-Analysis, Inc., Wilmington, DE or Midwest Microlab, Indianapolis, IN.

2.2. Synthesis of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2

OCH3TMPA (100 mg, 0.31 mmol) was dissolved in 3 mL of acetone in a 20-mL scintillation vial. To this brown solution, solid CuII(ClO4)2•6H2O (110 mg, 0.30 mmol, 0.95 equiv.) was added, with stirring, and the solution immediately turned green. After stirring for 30 minutes, 17 mL of diethyl ether was added, affording a green precipitate. This precipitate was collected, redissolved in 1 mL of acetone, and this solution was layered with diethyl ether (19 mL) and left overnight. Then, the supernatant liquid was decanted and the resulting green solid was dried in vacuo to give 145 mg (80.4%) of a green powder. UV-vis (butyronitrile) λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 280 (7900), 640 (70), and 830 (185). EPR spectrum (butyronitrile, 64 K): gꓕ = 2.20, Aꓕ = 110 G, gǁ = 1.97. ATR-IR spectrum is shown in Figure S1. ESI-MS (m/z, Figure S2): 481.5 [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(Cl04)]+. Calcd for C19H22N4Cl2CuO10: C, 37.98; H, 3.69; N, 9.32. Found: C, 37.86; H, 3.64; N, 8.83.

Note: Although we have not experienced any difficulties, perchlorate salts are known to be explosive and caution must be taken when handling them.

2.3. Synthesis of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI](B(C6F5)4)•2H2O

In the glovebox, OCH3TMPA (186 mg, 0.581 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of THF in a 20-mL scintillation vial. To this brown solution, solid [CuI(CH3CN)4](B(C6F5)4 (522 mg, 0.576 mmol, 0.99 equiv.) was added, with stirring, and the solution immediately turned golden yellow. After stirring for 15 minutes, 18 mL of pentane was added, affording a yellow-brown precipitate. This precipitate was collected, re-dissolved in 2 mL of THF, filtered through a pad of celite, and precipitated by addition of 18 mL of pentane. The supernatant liquid was decanted and the resulting yellow-brown solid was dried in vacuo to give 550 mg (86.9% yield) of the product. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): 8.70 (d, 4.92 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (td, 7.72 Hz, 1.64 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (t, 8.32 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (m, 4H), 7.08 (d, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, 8.36 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (s, 2H), 4.09 (s, 4H), 3.92 (s, 3H). Calcd for C19H20N4Cl2Cu09: C, 46.99; H, 2.20; N, 5.10. Found: C, 46.31; H, 2.08; N, 4.95.

2.4. Low-temperature UV-vis spectroscopy studies: CuI/O2 chemistry

In an inert atmosphere glovebox, [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ (2 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of MeTHF (0.19 mM). Typically, 2 mL of this solution was added to a Schlenk cuvette, followed by 0.5 mL of MeTHF to give a final copper concentration of 0.15 mM. The cuvette, capped with a septum and parafilmed under nitrogen, was subsequently cooled to cryogenic temperatures (−80 or −135 °C, waiting ten minutes to ensure full temperature equilibration). Dioxygen was then bubbled through the solution for 15 seconds and UV-vis spectra were recorded every 30 seconds.

2.5. Substrate reactivity studies of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+

Cuvettes were prepared as in section 2.4, but after full formation of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ in MeTHF at −125 °C (typically ~10 minutes), 50 μL (50 equivalents relative to [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+) of a solution of substrate (p-methoxy-2,6-di-tert-butylphenol (p-OMe-2,6-DTBP) or 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (DTBP)) in MeTHF was added and the reaction was allowed to go to completion (as monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy). For the reaction with DTBP, after the reaction was complete the solvent was removed in vacuo and the resulting residue was dissolved in 1.07 mL total of CH3OH (0.1 mL of which was from a 13.2 mM solution of dodecane for use as internal standard) and subjected to GC analysis. The chromatograms thus obtained were compared to standard calibration curves to obtain yields of the reactions.

2.6. EPR spectroscopic studies

In an inert atmosphere glovebox, a 1.51 mM solution of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ was prepared. To quartz 5 mm (outer diameter) EPR tubes was added 0.3 mL of this solution, followed by various amounts of MeTHF (0.1 to 0.02 mL, depending on other substrates added) and capped with rubber septa (Final [Cu] = 1.13 mM for monocopper complexes or 0.56 mM for dicopper species). EPR samples were cooled to −80 °C in an acetone/dry ice cold bath or to −130 °C in a pentane/liquid nitrogen cold bath. Subsequently, O2 was bubbled through the solutions for 15 seconds which were then either immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen or allowed to react for 30 minutes before freezing to interrogate reactive species. For substrate reactivity studies, substrate (p-methoxy-2,6-di-tert-butylphenol or 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, 50 μL of a MeTHF solution, 50 equiv. based on concentration of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+) was added after dioxygen bubbling. The solution was mixed by bubbling Ar and reactions were allowed to react for 30 minutes before being frozen in liquid nitrogen.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Examining ligand properties by characterizing [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2

In order to determine the preferred copper(II) geometry imposed by OCH3TMPA, as well as its donating capabilities (CuII/I redox potential) compared to other TMPA-based ligands, the physical-spectroscopic properties of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 were examined (Figure 1). The relative intensities of the d-d transitions, as observed by UV-vis spectroscopy, for synthetic copper(II) complexes have been reported to distinguish between trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) vs. square pyramidal geometry [24–26]. The UV-vis signature of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2, taken in butyronitrile at room temperature, showed the lower energy d-d transition (830 nm) is more intense than the one at higher energy (640 nm), suggesting a TBP geometry (Figure 1B). The EPR spectrum of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 at 64 K (frozen solution) in butyronitrile exhibits a reverse axial signal, which is also indicative of TBP geometry (Figure 1C) [27]. This preferred geometry varies from known crystallographic data obtained for similar TMPA-derived ligands, wherein a sterically bulky moiety favors a square pyramidal geometry, presumably to minimize steric clash between the 6-pyridyl substituent and the fifth, exogenous ligand (Figure 2, Table 1). Thus, after all, the 6-methoxy substituent in the OCH3TMPA ligand is not imposing a significant effect, as the coordination geometry of Cu(II)-TMPA’s without any 6-pyridyl substituents (i.e., [(TMPA)CuII(X)]2+/1+ (X = a neutral ligand like MeCN or an anionic ligand such as chloride or nitrite) are also always found in a TBP geometry.

Figure 1.

(A) Depiction of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2, emphasizing the 6-pyridyl methoxy substituent. (B) UV-vis spectra of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 (0.13 mM) in butyronitrile at room temperature (RT). Inset: UV-vis spectra of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 (1.3 mM) in butyronitrile at RT. (C) EPR spectrum of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 (1 mM) in butyronitrile at 64 K. (D) Cyclic voltammetry of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 (1.4 mM) in a 0.1 M electrolyte solution of tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) in CH3CN at RT.

Figure 2.

TMPA and TMPA-based ligands bearing substituents in their 6-pyridyl positions.

Table 1.

CuII/I reduction potentials and CuII geometries for TMPA-based ligands.

| Copper Complex | Liganda | CuII/I Redox Potential (mV)b | [(XTMPA)CuII(L)] Geometry (L, τ5)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| [(TMPA)CuI(CO)]+ | TMPA | −410 [28] | TBP (CI−, 1.00) [24] |

| [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)]2+ d | OCH3TMPA | −350 | TBP |

| [(CH3TMPA)CuI]+ | CH3TMPA | −350 [29] | Square Pyramidal (Cl−, 0.17) [30] |

| [(PhTMPA)CuII(CH3CN)]2+ | PhTMPA | −370 [31] | Square Pyramidal (CH3CN, 0.12) [31] |

| [(PhtBuTMPA)CuI(CO)]+ | PhtBuTMPA | −325 [28] | Square Pyramidal (Acetone, 0.19)[32] |

| [(BATMPA)CuII(CH3COCH3)]2+ | BATMPA | −350 [33] | Square Pyramidal (Cl− 0.20) [34] |

Cyclic voltammetry of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)](ClO4)2 in CH3CN reveals a quasi-reversible voltammogram (ΔEp = 145 mV; however the anodic and cathodic peak currents are in an approximate ratio of 1:1), with a reduction potential of −0.35 V vs. Fc+/0 (Figure 1D). The CuII/I reduction potential of this system is slightly more positive than that reported for the parent TMPA complex (−0.41 V) and is consistent with values determined for several other TMPA derivatives bearing substituents in the 6-pyridyl position (Figure 2, Table 1). The more positive potential is thought to be due to elongation of the Cu-Npy containing the substituent as a result of steric clash, yielding poorer donation to the copper ion.

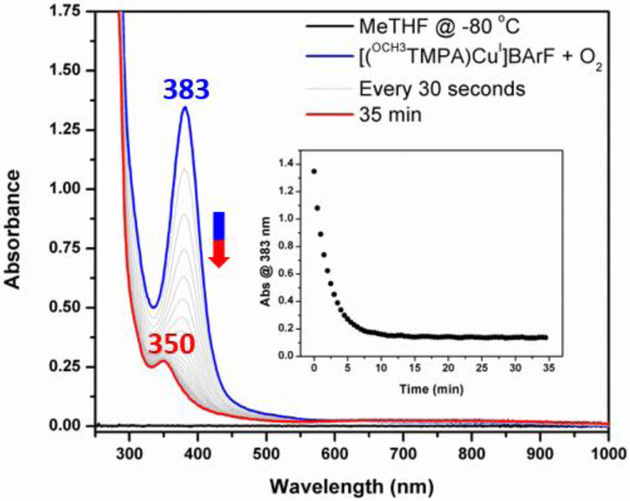

3.2. Reactivity of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ with O2 at −80 °C

With a better understanding of the ligand properties, the CuI/O2 chemistry was then investigated. Upon bubbling O2 through a solution of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ in MeTHF at −80 °C, the characteristic UV-vis signature [9] of a bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex (λmax = 383 nm, ε = 13000 M−1 cm−1), [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, was observed (Figure 3). Interrogation of this or other species observed in this study, using resonance Raman spectroscopy, was not carried out. However, also supporting this formulation is its EPR silence [9]. However, with a similarity to some other TMPA-based O complexes [18], this species was unstable under these conditions and fully decomposed to a new compound (λmax = 350 nm, ε = 2650 M−1 cm−1) within ten minutes. The final complex is EPR silent (perpendicular mode), suggesting the formation of an antiferromagnetically coupled dicopper(II) complex with bridging ligand(s). However, interrogation of the final reaction mixture by ESI-MS showed only peaks corresponding to monocopper products (Figure S3), which may be due to (i) the dicopper(II) complexes breaking apart into mono-copper species or (ii) reduction of the (di)copper(II) products from the ESI-MS ionization used.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra showing the thermal decomposition of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ (blue spectrum) in MeTHF at −80 °C to give a new species (red spectrum) (Inset) Monitoring the decomposition of the bis-μ-oxo intermediate (λmax = 383 nm) over time.

3.3. Reactivity of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ with O2 at −135 °C

Numerous investigations have shown that examination of copper(I)-dioxygen chemistry at very low temperatures (i.e., ≤ −125 °C) results in stabilization of previously highly reactive intermediates, facilitating their characterization [20,23,36–39]. Consequently, the chemistry of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ with dioxygen was re-investigated at −135 °C in MeTHF. Surprisingly, the initial copper-dioxygen adduct that is observed by UV-vis spectroscopy is a cupric superoxide complex, [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+, verified by the diagnostic highly characteristic absorption features [1, 16] (λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 433 (3480), 595 (1370), 770 (1370), Figure 4), previously assigned as superoxo-to-Cu(II) LMCT and intraligand superoxide anion CT bands [40,41]. However, this copper(II) superoxide species is not stable, even at −135 °C, and slowly (~ 60 min.) converts to the bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) species that is initially observed at −80 °C (Figure 4). This is the first time that this type of transformation, an apparently direct conversion of a copper(II) superoxo complex to bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) species, has been observed in copper-dioxygen chemistry. At this temperature (and even up to −110 °C) [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ is now stable, which has allowed for investigation of its reactivity (vide infra). Both the initial cupric superoxide intermediate and the final bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex are EPR silent (perpendicular mode), consistent with their S = 1 and S = 0, respectively, states.

Figure 4.

(Left) UV-vis monitoring of the conversion of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+ (green spectrum) to [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ (blue spectrum) over time. (Right) Change in absorbance at 433 nm (green) and 383 nm (blue) to show decay of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+ and formation of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, respectively.

The initial formation of [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(O2•−)]+ may be a result of the ligand’s preferred copper(II) geometry of TBP. All TMPA-based cupric superoxide species, which typically do not contain sterically bulky 6-pyridyl substituents, are postulated to have a TBP geometry, with the superoxide ligand binding end-on to copper [1,8]. However, electron-electron repulsion between the methoxy and superoxide entities may elongate that Cu-Npy bond, allowing for square pyramidalization when a second copper(I) complex approaches, favoring the bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) formulation (Scheme 2) instead of a trans-peroxo dicopper(II) complex, which is normally observed for tripodal tetradentate N4 chelates.

3.4. Examining the oxidizing potential of [{{OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+

It has previously been shown that bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) species are capable of oxidizing substrates containing weak-to-moderately strong O–H or C–H bond dissociation energies (BDEs) [8,18,42,43]. Therefore, to provide further evidence for the formulation of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, the substrates p-methoxy-2,6-di-tert-butylphenol (p-OMe-2,6-DTBP) and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (DTBP) were added in excess to the low-temperature stable complex and the reactions were monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy. The isosbestic reactions with phenolic substrates confirm that [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, like other bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complexes, is capable of net hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from phenols, while possibly concomitantly forming a bis-μ-hydroxo dicopper(II) compound (Scheme 3), which are common copper complex side-products [43]. For instance, the p-methoxy-2,6-di-tert-butylphenoxyl radical is observed in both the UV-vis (sharp peak, λmax = 408 nm) and EPR (sharp signal at g = 2.0) spectra from the reaction of p-OMe-2,6-DTBP with [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ (Figure 5). The reaction of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ with DTBP (Figure S4) afforded the usual coupled phenolic product 3,3’,5,5’-tetra-tert-butyl-(1,1’-biphenyl)-2,2’-diol in high yield (88.9%, assuming one equivalent of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ reacts with two equivalents of DTBP to give the coupled product) as verified by gas chromatography (Figure S5). Unlike other previously reported dicopper(III) bis-μ-oxo complexes, [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ showed little to no reactivity with substrates containing moderately strong C–H bond dissociation energies (BDEs) such as toluene [18,44]. This may be due to the lower temperature (−125 vs. −80 °C) at which these reactions are monitored at in this current study or due to a not fully understood inherently lower oxidizing capability of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ compared to previously reported dicopper(III) bis-μ-oxo species.

Scheme 3.

Proposed reaction of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ with p-OMe-2,6-DTBP and DTBP.

Figure 5.

(A) Monitoring of the reaction of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ (blue spectrum) with p-OMe-2,6-DTBP (final spectrum in magenta) with isosbestic points at λ = 320 and 353 nm. (B) EPR spectra of [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+ before (black, silent EPR) and after (magenta) its reaction with p-OMe-2,6-DTBP. Note: The sharp peak at 408 nm UV-vis feature in (A) and the sharp g = 2.0 signal in (B) are both indicative of formation of the stable p-OMe-2,6-DTBP radical.

4. Conclusions

Biomimetic studies on copper-dioxygen chemistry have provided valuable insights into processes which may occur in copper-containing metalloenzymes or chemical systems as applied to catalytic oxidation of organic substrates. Characterization of novel copper complexes bearing the ligand OCH3TMPA have shown that this ligand, like many other TMPA derivatives favors trigonal bipyramidal copper(II) geometry, and the CuII/I redox potential determined from cyclic voltammetry on [(OCH3TMPA)CuII(OH2)]2+ is similar to other ligands bearing sterically bulky 6-pyridyl substituents. At higher cryogenic temperatures (−80 °C ≥ T ≥ −115 °C) oxygenation of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ results in the immediate formation of the bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex [{(OCH3TMPA)CuIII}2(O2−)2]2+, although this complex is only stable at −115 °C or lower temperatures. However, when dioxygen is bubbled through a solution of [(OCH3TMPA)CuI]+ at −135 °C, the initial adduct formed is a cupric superoxide species, which then seemingly converts directly to the bis-μ-oxo dicopper(III) complex observed at higher temperatures. This specific chemical transformation is unprecedented, and the present finding furthers our knowledge of the influence of ligand properties on copper-dioxygen reactivity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Novel CuI/O2 chemistry using the TMPA-based ligand, OCH3TMPA

Cuprous complex ligated by OCH3TMPA plus O2 forms a cupric superoxide at −135 °C

Cupric superoxide species directly converts to a dicopper(III) bis-μ-oxo complex

The dicopper(III) bis-μ-oxo complex can oxidize phenolic substrates

Acknowledgments

The research support of the USA National Institutes of Health (GM 28962) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found online.

References

- [1].Liu JJ, Diaz DE, Quist DA, Karlin KD, Isr. J. Chem 56 (2016) 738–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Hadt RG, Tian L, Chem. Rev 114 (2014) 3659–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Quist DA, Diaz DE, Liu JJ, Karlin KD, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 22 (2017) 253–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Allen SE, Walvoord RR, Padilla-Salinas R, Kozlowski MC, Chem. Rev 113 (2013) 6234–6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McCann SD, Lumb JP, Arndtsen BA, Stahl SS, ACS Cent. Sci 3 (2017) 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu C-C, Mou C-Y, Yu SS-F, Chan SI, Energy Environ. Sci 9 (2016) 1361–1374. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Snyder BER, Bols ML, Schoonheydt RA, Sels BF, Solomon EI, Chem. Rev 118 (2018) 2718–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Elwell CE, Gagnon NL, Neisen BD, Dhar D, Spaeth AD, Yee GM, Tolman WB, Chem. Rev 117 (2017) 2059–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP, Chem. Rev 104 (2004) 1013–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kieber-Emmons MT, Ginsbach JW, Wick PK, Lucas HR, Helton ME, Lucchese B, Suzuki M, Zuberbuhler AD, Karlin KD, Solomon EI, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 53 (2014) 4935–4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim S, Ginsbach JW, Billah AI, Siegler MA, Moore CD, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 8063–8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jacobson RR, Tyeklar Z, Farooq A, Karlin KD, Liu S, Zubieta J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 110 (1988) 3690–3692. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Uozumi K, Hayashi Y, Suzuki M, Uehara A, Chem. Lett (1993) 963–966. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hayashi H, Fujinami S, Nagatomo S, Ogo S, Suzuki M, Uehara A, Watanabe Y, Kitagawa T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 122 (2000) 2124–2125. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang CX, Kaderli S, Costas M, Kim E-I, Neuhold Y-M, Karlin KD, Zuberbühler AD, Inorg. Chem 42 (2003) 1807–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yamaguchi S, Wada A, Funahashi Y, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Jitsukawa K, Masuda H, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2003 (2003) 4378–4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wada A, Honda Y, Yamaguchi S, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Jitsukawa K, Masuda H, Inorg. Chem 43 (2004) 5725–5735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maiti D, Woertink JS, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, Inorg. Chem 47 (2008) 3787–3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lee JY, Peterson RL, Ohkubo K, Garcia-Bosch I, Himes RA, Woertink J, Moore CD, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 9925–9937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bhadra M, Lee JYC, Cowley RE, Kim S, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 140 (2018) 9042–9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ehudin MA, Schaefer AW, Adam SM, Quist DA, Diaz DE, Tang JA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, Submitted [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chai C, Armarego WLF, Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peterson RL, Himes RA, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Tian L, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 133 (2011) 1702–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Karlin KD, Hayes JC, Juen S, Hutchinson JP, Zubieta J, Inorg. Chem 21 (1982) 4106–4108. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wei N, Murthy NN, Karlin KD, Inorg. Chem 33 (1994) 6093–6100. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee Y, Park GY, Lucas HR, Vajda PL, Kamaraj K, Vance MA, Milligan AE, Woertink JS, Siegler MA, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, Inorg. Chem 48 (2009) 11297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Garribba E, Micera G, J. Chem. Educ 83 (2006) 1229–1232. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lucas HR, Meyer GJ, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 132 (2010) 12927–12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hayashi H, Uozumi K, Fujinami S, Nagatomo S, Shiren K, Furutachi H, Suzuki M, Uehara A, Kitagawa T, Chem. Lett 31 (2002) 416–417. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Maiti D, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Itoh S, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 130 (2008) 5644–5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kunishita A, Kubo M, Ishimaru H, Ogura T, Sugimoto H, Itoh S, Inorg. Chem 47 (2008) 12032–12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Maiti D, Lucas HR, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 129 (2007) 6998–6999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lee JY, PhD Thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maiti D, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Karlin KD, Inorg. Chem 47 (2008) 8736–8747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, van Rijn J, Verschoor GC, J. Chem. Soc. Dalt. Trans 251 (1984) 1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mirica LM, Vance M, Rudd DJ, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI, Stack TDP, Science 308 (2005) 1890–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Citek C, Lyons CT, Wasinger EC, Stack TDP, Nat. Chem 4 (2012) 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Citek C, Herres-Pawlis S, Stack TDP, Acc. Chem. Res 48 (2015) 2424–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chiang L, Keown W, Citek C, Wasinger EC, Stack TDP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 55 (2016) 10453–10457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Woertink JS, Tian L, Maiti D, Lucas HR, Himes R. a, Karlin KD, Neese F, Würtele C, Holthausen MC, Bill E, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S, Solomon EI, Inorg. Chem 49 (2010) 9450–9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ginsbach JW, Peterson RL, Cowley RE, Karlin KD, Solomon EI, Inorg. Chem 52 (2013) 12872–12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Shearer J, Zhang CX, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 127 (2005) 5469–5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lewis EA, Tolman WB, Chem. Rev 104 (2004) 1047–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lucas HR, Li L, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Vance MA, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131 (2009) 3230–3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.