Abstract

Recent literature documents that women comprise an increasing proportion of the neurology workforce but still lag behind male counterparts in publications and promotion. There are many reasons for gender disparities in neurology including family responsibilities, different career goals, lack of mentorship, cultural stereotypes, lack of institutional funding, biases, and professional isolation. Another contributing factor receiving relatively little recognition is the imposter phenomenon. This review highlights recent literature on gender differences in neurology, the definition of the imposter phenomenon, and research on the imposter phenomenon in academic medicine. Approaches for managing the imposter phenomenon are described including personal, mentoring, and institutional strategies. Further research is needed to understand the frequency of the imposter phenomenon at different levels of seniority and optimal strategies for prevention and management.

Women comprise an increasing proportion of the neurology workforce, accounting for 37% of full-time neurology faculty,1 31.5% of US-based American Academy of Neurology (AAN) neurologist members,2 and 48% of neurology residents.1 Men continue to outnumber women at all academic faculty ranks at top-ranked academic neurology programs, however, with the difference increasing with advancing rank even when controlling for years since medical school graduation.3 Such differences are also seen across US neurology departments. In 2015, there were more women than men instructors (54%) but less female representation at the assistant (45%), associate (35%), and full (19%) professor levels.1 Women at top-ranked neurology programs also have fewer publications than men at all academic ranks.3 Although female first and senior authorship has significantly increased in 3 high impact factor neurology journals over the past 35 years, the percent of first (24.6%) and senior (18.1%) female authorship still lagged significantly behind males in 2015.4

Both articles3,4 and an associated editorial5 postulate various reasons for these discrepancies including family responsibilities, different career goals, lack of same-sex mentorship, cultural stereotypes, lack of institutional funding, biases in research grant and manuscript review processes, and professional isolation. It is critical to identify and address these systemic barriers to women's careers in neurology in both academics and private practice. One potentially important contributor that is often overlooked is the “imposter phenomenon” (IP).

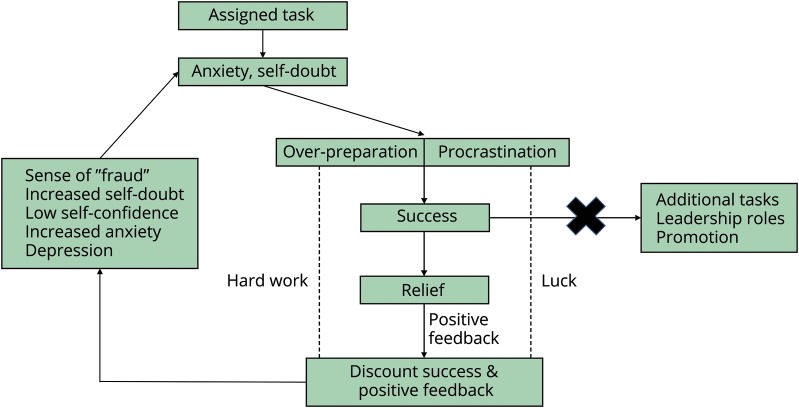

IP is a pattern of chronic feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt associated with a fear of being discovered as a “fraud.” With IP, a person believes that he or she has fooled others into thinking they are competent.6 Such feelings occur even in the setting of achievement and success.7,8 Most people feel like imposters at times,9 but individuals with IP have an exaggerated and irrational inability to internalize a sense of accomplishment.6,9 This leads to a cycle of maladaptive behaviors (e.g., extreme overpreparation or procrastination) that perpetuates the perceived fraudulence. Because individuals with IP discount success as due to luck or hard work rather than their own abilities, they are less likely to accept or pursue competence-related opportunities (figure).6 In this manner, women in neurology may be less likely to achieve higher academic faculty appointments or publication in higher tier journals in part because they feel inadequate for such opportunities and do not pursue them.

Figure. The impostor phenomenon cycle.

Individuals with the imposter phenomenon (IP) experience anxiety and self-doubt when facing tasks, leading to maladaptive behaviors. Rather than believing that success relates to self-competence and accepting additional responsibilities, they discount the success as secondary to external factors such as luck or hard work alone. Individuals with IP have fixed beliefs that success does not reflect true abilities, so they disregard positive feedback. This leads to an increased sense of fraudulence and more self-doubt, anxiety, and depression. Adapted from: Sakulku J, Alexander J. The impostor phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioral Science 2011;6:75–97.

A 2018 American College of Physicians position paper about achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement identified IP as one of the challenges facing women in medicine.10 The authors described IP as a barrier to the advancement of women in medicine that may cause them to pass up opportunities for career advancement.10 This is consistent with research outside medicine showing that IP is associated with less career planning, career striving, and motivation to pursue leadership.11

IP is well recognized in professions outside medicine and was popularized as “the confidence gap” by journalists Claire Shipman and Katty Kay.12 Their work highlights how women underestimate their abilities, predict they will underperform, and view themselves less deserving of advancement even when research shows that they perform at the same level as male counterparts. This is in contrast to men, who tend to overestimate their abilities.12 While frequently highlighted as occurring in women, IP is experienced by both genders.6,8 It is more common in individuals with perfectionism and neuroticism6 and may relate in part to family dynamics and social experiences.6,8

IP is documented in medical trainees at various levels. In a 1998 survey, 30% of medical, dental, nursing, and pharmacy students scored over the cutoff identifying IP on the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale (CIPS). Scale scores were higher in women (57.83 ± 14.89 vs 52.08 ± 13.03, p < 0.001), and IP was more common in women than men (37.8% vs 22%, p < 0.001). CIPS score was one of the strongest predictors of students' distress, along with perfectionism.13 IP was even more common in a recent study, occurring in 49.4% of female and 23.7% of male medical students. It was significantly associated with burnout, particularly various components of exhaustion (p < 0.05), cynicism, and depersonalization (both p < 0.01).7 In residency, 41% of female and 24% of male family practice residents scored above the CIPS cutoff despite the belief that they were well trained. Imposter symptoms correlated highly with anxiety and depression.14 In a survey of Canadian internal medicine residents, IP occurred in 44% of the sample: 52% women (95% CI 34%–70%) and 32% (95% CI 16%–53%) men.15

No identified publications examined IP frequency in medical practice, but interviews with academic physicians about experience with underperformance identified IP as a frequent theme, particularly at times of transition or new professional challenges.16 In higher education faculty, IP thoughts were moderately prevalent, with the highest levels in untenured faculty.17 Competitive, stressful work environments, certain personality traits (e.g., achievement orientation, neuroticism, and conscientiousness), and perfectionist tendencies were associated with IP.17

Tackling the imposter phenomenon

Strategies targeting IP are part of a multicomponent approach to address women's roles in neurology. How can individuals experiencing IP and leaders in neurology address this phenomenon, not only in women but also in men? Research suggests that opportunities include personal approaches, mentoring, and targeted programs (departmental, institutional, and professional).

Personal approaches

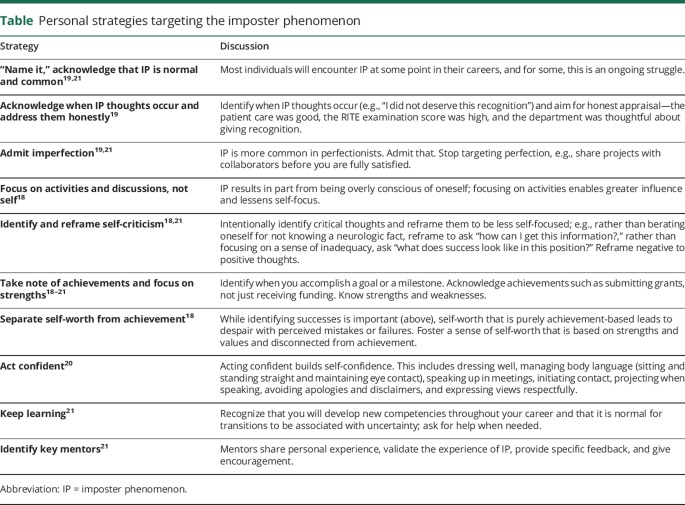

Personal strategies for combating IP come from business18–20 and nursing21 publications world but are clearly relevant for individuals in medicine (table).

Table.

Personal strategies targeting the imposter phenomenon

Strategies for mentors

Mentoring is critical for targeting IP,7,17 but physicians reported that admitting to IP and IP discussions between mentors and mentees were uncommon.16 Suggested teaching and mentoring approaches for individuals with IP include frank discussion of IP frequency,14 providing frequent specific feedback regarding performance,7,14 avoiding shame-based education,7 fostering time management strategies,14 and using programs to enhance self-efficacy.7 Mentors can also encourage mentees to adopt personal strategies for combating IP (table). Negative feedback should be used cautiously and strategically with individuals with IP because of risks of validating perceived incompetence.8 Women with IP may exert more effort and perform better after receiving negative feedback,8 but this strategy may not translate to increased confidence or advancement.12 Mentorship on the topic of IP is part of the broader role of mentorship for women physicians.10,22 A lack of adequate mentors and role models is one reason women are less likely to enter academic medicine.23 Sponsorship—support from a senior leader to promote individuals with untapped potential—is another way to advance careers of women in medicine,24 but women must be willing to accept these opportunities.

Departmental, institutional, and professional programs

Departmental, institutional, and professional programs can target IP to promote careers of women in medicine. Discussing IP is part of some college undergraduate and graduate orientation events and is also promoted for faculty orientation.25 A 2-week interprofessional educational program and 1-day workshop for clinical nurse specialists resulted in greater understanding of IP and a sense of empowerment.21 Many departments and academic institutions are developing local programs to advance the careers of women in academic medicine. Educational curricula can promote women's careers and address IP through skill development, mentorship, and networking.

The AAN has educational opportunities such as the “Women Leading in Neurology” program and annual meeting courses promoting women's leadership skills. The AAN also supports female neurologists by providing data on compensation for use in negotiation. Additional suggestions from the AAN's Gender Disparity Task Force include improving transparency, addressing implicit bias, development and support of mentors, promotion of different practice options, funds for small projects, legislative approaches, and further research.2 The American Association of Medical Colleges has leadership development programs specifically targeting women at different career stages.

Conclusions

Recent publications document positive trends for women's roles in neurology; however, areas of concern remain.1–4 Identifying and addressing systemic and institutional biases contributing to gender disparities are important, but modifiable personal barriers such as IP deserve recognition and intervention. Research is needed to understand the frequency with which IP occurs at faculty levels—regardless of gender—and the degree to which this may limit professional development and/or contribute to burnout. Optimal strategies for addressing IP require further investigation including identifying whether targeting IP improves outcomes such as career satisfaction and quality of life. Neurologists experiencing IP can strategically modify thoughts and behaviors to help address IP tendencies, but departments and mentors play a major role in identifying faculty members with IP and providing targeted strategies to overcome IP and personalized career development opportunities.

Appendix. Author contributions

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

M.J. Armstrong receives compensation from the AAN for work as an evidence-based medicine methodology consultant and serves on the level of evidence editorial board for Neurology and related publications (uncompensated). She receives research support from Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (K08HS24159), a 1Florida ADRC (AG047266) pilot grant, and as the local PI of a Lewy Body Dementia Association Research Center of Excellence. She receives royalties from the publication of the book Parkinson's Disease: Improving Patient Care, and she has received honoraria for presenting at the AAN annual meeting (2017) and participating in Medscape CME. L.M. Shulman receives research support from the NIH (1R01AG059651-01 and 1R21AG058118-01), Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (3P30AG028747-13S30), University of Maryland Center for Health-Related Informatics and Bioimaging, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (investigator-initiated study), Eugenia and Michael Brin, and The Rosalyn Newman Foundation. She receives royalties from Johns Hopkins University Press and Oxford University Press. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015-2016 [online]. Available at: aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed June 26, 2018.

- 2.American Academy of Neurology. Gender Disparity Task Force report [online]. Available at: aan.com/conferences-community/member-engagement/Learn-About-AAN-Committees/committee-and-task-force-documents/gender-disparity-task-force-report/. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 3.McDermott M, Gelb DJ, Wilson K, et al. Sex differences in academic rank and publication rate at top-ranked US neurology programs. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:956–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pakpoor J, Liu L, Yousem D. A 35-year analysis of sex differences in neurology authorship. Neurology 2018;90:472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen FE. Closing the sex divide in the emerging field of neurology. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:920–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakulku J, Alexander J. The imposter phenomenon. Int J Behav Sci 2011;6:75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villwock J, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Imposter syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ 2016;7:364–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badawy RL, Gazdag BA, Bentley JR, Brouer RL. Are all imposters created equal? Exploring gender differences in the imposter phenomenon-performance link. Pers Individ Dif 2018;131:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gravois J. You're Not Fooling Anyone. The Chronicle of Higher Education [serial online] 2007: November 9, 2007. Available at: chronicle.com/article/Youre-Not-Fooling-Anyone/28069. Accessed October 18, 2018.

- 10.Butkus R, Serchen J, Moyer DV, et al. Achieving gender equity in physician compensation and career advancement: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:721–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neureiter M, Traut-Mattausch E. An inner barrier to career development: preconditions of the impostor phenomenon and consequences for career development. Front Psychol 2016;7:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay K, Shipman C. The confidence gap [online]. The Atlantic 2014: May 2014. Available at: theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/05/the-confidence-gap/359815/. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 13.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ 1998;32:456–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oriel K, Plane MB, Mundt M. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam Med 2004;36:248–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legassie J, Zibrowski EM, Goldszmidt MA. Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1090–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaDonna KA, Ginsburg S, Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: What physicians' self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad Med 2018;93:763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchins HM. Outing the imposter: A study exploring imposter phenomenon among higher education faculty. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 2015;27:3–12. doi: 10.1002/nha3.20098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ioli J. Three secrets that help successful women get over self-doubt. Forbes Community Voice [serial online] 2016: July 26, 2016. Available at: forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2016/07/29/three-secrets-that-help-successful-women-get-over-self-doubt/#318738297b06. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 19.Stahl A. Feel like a fraud? Here's how to overcome imposter syndrome. Forbes [serial online]. 2017: December 10, 2017. Available at: forbes.com/sites/ashleystahl/2017/12/10/feel-like-a-fraud-heres-how-to-overcome-imposter-syndrome/#579fae874d31. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 20.Zenger J. The confidence gap in men and women: why it matters and how to overcome it. Forbes [serial online] 2018: April 8, 2018. Available at: forbes.com/sites/jackzenger/2018/04/08/the-confidence-gap-in-men-and-women-why-it-matters-and-how-to-overcome-it/#693bf0e43bfa. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 21.Haney TS, Birkholz L, Rutledge C. A workshop for addressing the impact of the imposter syndrome on clinical nurse specialists. Clin Nurse Spec 2018;32:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voytko ML, Barrett N, Courtney-Smith D, et al. Positive value of a women's junior faculty mentoring program: a mentor-mentee analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet 2016;388:2948–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travis EL, Doty L, Helitzer DL. Sponsorship: a path to the academic medicine C-suite for women faculty? Acad Med 2013;88:1414–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkman A. The imposter phenomenon in higher education: incidence and impact. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 2016;16:51–60. [Google Scholar]