Abstract

Background

Multiple acute cerebral territory infarcts of undetermined origin are typically attributed to cardioembolism, most frequently atrial fibrillation. However, the importance of 3-territory involvement in association with malignancy is under-recognized. We sought to highlight the “Three Territory Sign” (TTS) (bilateral anterior and posterior circulation acute ischemic diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI] lesions), as a radiographic marker of stroke due to malignancy.

Methods

We conducted a single-center retrospective analysis of patients from January 2014 to January 2016, who suffered an acute ischemic stroke with MRI-DWI at our institution, yielding 64 patients with a known malignancy and 167 patients with atrial fibrillation, excluding patients with both to eliminate bias. All DWI images were reviewed for 3-, 2-, and 1-territory lesions. Chi-square test of proportion was used to test significance between the 2 groups.

Results

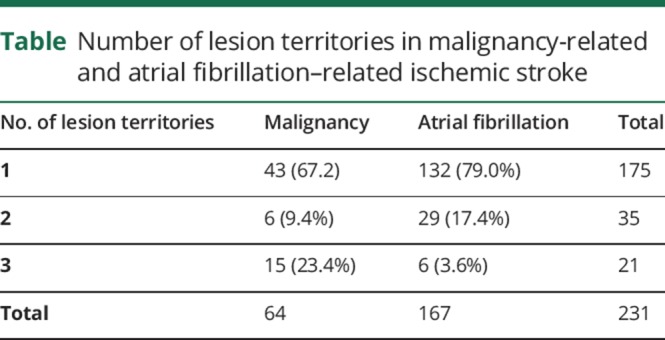

We found an association between the groups (malignancy vs atrial fibrillation) and the number of territory infarcts (p < 0.0001). Pairwise comparisons using the Holm p value adjustment showed no difference between 1- and 2-territory patterns (p = 0.465). However, the TTS was 6 times more likely observed within the malignancy cohort as compared to patients with atrial fibrillation (23.4% [n = 15] vs 3.5% [n = 6]) and was different from both 1-territory (p < 0.0001) and 2-territory patterns (p = 0.0032).

Conclusion

The TTS is a highly specific marker and 6 times more frequently observed in malignancy-related ischemic stroke than atrial fibrillation-related ischemic stroke. Evaluation for underlying malignancy in patients with the TTS is reasonable in patients with undetermined etiology.

Although the incidence of cerebrovascular ischemic events in patients with malignancy has been observed in up to 15% of patients,1 identifying malignancy as a cause of stroke is frequently overlooked until a second event occurs.2 Furthermore, identifying occult malignancy in patients with embolic strokes of undetermined source (ESUS) is challenging in the absence of clear systemic manifestations or obvious clinical findings and cost-effective methods.

In patients with ESUS, multiple cerebral territory acute infarctions are most frequently attributed to an “embolic phenomenon” such as occult atrial fibrillation with the etiology yet to be determined.3,4 However, the yield of detecting occult paroxysmal atrial fibrillation is low, ranging from 2.7% on admission ECG up to 30% with an implantable loop recorder after 18 months of monitoring, leaving many patients with no underlying source.5 The concept of multiple territory infarctions in malignancy is not novel and has been previously reported.6,7 However, there are no studies comparing the diagnostic value of acute stroke MRI-diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) patterns in patients with malignancy as compared to atrial fibrillation.

We have previously reported the diagnostic value of the “Three Territory Sign” (TTS) as a radiographic MRI-DWI marker of malignancy-associated stroke (Trousseau syndrome).8 In that study, we retrospectively evaluated in a blinded fashion all MRI of patients with DWI restriction involving 3 cerebral vascular territories (bilateral anterior and posterior) over the course of 12 months at our institution and identified 19 separate etiologies. Not only was the underlying malignancy the most frequent etiology in patients with the TTS, in the absence of any identifiable embolic source acute ischemic infarction with cancer-associated hypercoagulation (Trousseau syndrome) accounted for 75% of all cases.8 The definition of Trousseau syndrome has varied in the literature. For our study, we accept the definition per Varki,9 2007 as “unexplained thrombotic events that precede the diagnosis of an occult visceral malignancy or appear concomitantly with the tumor.”

In our current study, we sought to investigate the TTS in patients with acute stroke with known malignancy and no atrial fibrillation, in comparison to patients with known atrial fibrillation and no malignancy to assert its frequency and diagnostic value.

Methods

This was a retrospective study comparing 2 subgroups of patients among the cohort of patients admitted to our institution with acute ischemic stroke from January 2014 to 2016. After Hartford HealthCare (HHC) institutional review board approval, we cross-referenced all patients within our institutional cancer registry with our institution's stroke database (HHC-2015-0245) to identify patients with an established malignancy who suffered an acute ischemic stroke within the study timeframe and named this cohort the “malignancy group.” For the second cohort, we identified patients with known atrial fibrillation and acute ischemic stroke within our stroke database within the same timeframe and named this cohort the “A.fib” group. Patients with documented malignancy and atrial fibrillation based on chart review within the study timeframe were excluded. Only patients with completed and available MRI for review were included, whereas patients with missing records and/or imaging were excluded. Patients with concomitant possible etiologies for 3-territory DWI lesions based on the 19 separate etiologies previously identified were also excluded to eliminate sampling bias.8 For patients with 2 or more ischemic strokes within the study time frame, only their first stroke was included.

This yielded 64 patients in the first group (malignancy and no atrial fibrillation) and 167 patients in the second group (atrial fibrillation and no malignancy). A chart review for all patients was completed, evaluating clinical data, medical history, demographics, and imaging. For imaging, 3 ischemic stroke MRI-DWI patterns were identified in both cohorts. All patients must have had MRI with DWI and a completed neuroradiology report confirming acute ischemic stroke. MRI-DWI patterns were divided into 1, 2, or 3 territories as follows:

One Territory: Unilateral, single, or multiple acute ischemic strokes involving the anterior or the posterior circulation

Two Territory: Unilateral, single, or multiple acute ischemic strokes involving the anterior circulation plus posterior circulation, or bilateral anterior circulation

Three Territory: Bilateral, single, or multiple acute ischemic strokes involving the bilateral anterior and posterior circulation as established in our previous study8 (figure)

Figure. MR-DWI imaging.

MR-DWI patterns with cancer-associated hypercoagulable cerebral infarcts include pattern 1 (A, B—asterisk), pattern 2 (C, D—arrowhead), and pattern 3 (D—arrow).

Initial screening of imaging for all patients was performed using a neuroradiology report review. For all patients with more than 1 territory reported, independent review of imaging was completed to confirm 2- vs 3-territory designation based on our study criteria.

For patients within the malignancy group, all echocardiogram reports were reviewed to evaluate the possibility of vegetation's or other cardioembolic source. After designating all stroke patterns in both groups (1 vs 2 vs 3), the χ2 test of proportions was used to test for statistical significance (set at alpha ≤ 0.05). Post hoc pairwise comparison was completed to compare frequency of all 3 patterns in both groups using the Holm-Bonferroni p value adjustment.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Institutional IRB approval was received for this retrospective study.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

In patients within the malignancy group (n = 64), a total of 43 patients had the 1-territory infarct pattern (67.2%) and 6 patients had the 2-territory pattern (9.4%). The TTS was, however, observed in 15 patients (23.4%), representing almost 1 in 4 of all stroke patterns in patients with malignancy. Within the atrial fibrillation group, a total of 132 patients had the 1-territory stroke pattern (79%), 29 patients had the 2-territory pattern (17.4%) and only 6 had the TTS (3.5%). The overall association between number of territories and group was significant, but among pairwise comparisons using the Holm p value adjustment, no difference was found between the 1- vs 2-territory patterns (p = 0.465). However, the TTS was 6 times more likely observed within the malignancy cohort as compared to patients with atrial fibrillation and was different from both 1- (p < 0.0001) and 2-territory patterns (p = 0.0032) (table). The sensitivity and specificity of the three territory sign in malignancy-related acute ischemic stroke was 23.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 13.75%–35.69%) and 96.4% (95% CI 92.34–98.675), respectively. In the malignancy patients with the TTS, lung cancer was most frequently observed (40%, n = 6), followed by gastrointestinal malignancy (33.3%, n = 5), whereas the remaining 26.7% included 1 patient each with malignancy of the breast, kidney, cervical cancer, and lymphoma.

Table.

Number of lesion territories in malignancy-related and atrial fibrillation–related ischemic stroke

Although the 3-territory distribution is the most compelling MR imaging feature of malignancy-related ischemic infarctions, radiographic DWI patterns are often noted. These include nonenhancing, nonring clusters or single areas of restricted diffusion of 0.5–2 cm with a peripheral preference (pattern 1), uncommonly in a watershed distribution (pattern 2), or large vascular territories (pattern 3), with absence of diffuse cortical ribbon or deep gray involvement (figure). In contrast, patients with atrial fibrillation tend to have larger wedge-shaped infarctions in addition to multiple DWI lesions. One explanation may be due to the embolic mechanism of stroke in atrial fibrillation compared with intrinsic coagulation within the vessel lumen or artery-to-artery thrombosis observed in Trousseau syndrome.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study is to highlight the TTS as a radiographic marker of malignancy and its associated hypercoagulable state–related acute ischemic stroke. Not only was the TTS more prevalent in patients with malignancy, but it was also a more frequent DWI-MRI pattern in these patients compared with stroke-related atrial fibrillation. Based on our study, the frequency of acute 3-territory infarcts in atrial fibrillation is low and represented only in 1 of 25 patients compared with approximately 1 in 4 patients with malignancy. Despite this finding, multiple acute DWI strokes observed in >2 territories are frequently labeled “embolic” by radiologists and neurologists alike, and the search for occult atrial fibrillation typically ensues. Although the sensitivity of the TTS was low in our study, its specificity was high for malignancy-related ischemic stroke. Moreover, malignancy is the most common etiology of this radiographic sign as compared to atrial fibrillation and among all other potential causes.8

Patients with ESUS may represent up to 30% of all ischemic stroke patients and require an extensive workup to meet this criterion.5 In patients with no known malignancy, determining if the patient requires investigations to detect cancer in the absence of systemic manifestations can be challenging. Elevation in serum D-dimer levels has been associated with malignancy and as a surrogate measure of hypercoagulability in patients with stroke and malignancy.6,10

In a recent study of 1646 patients with ischemic stroke and 5% of this population with known malignancy, increased D-dimer, lower hemoglobin, smoking, and suffering a stroke of undetermined etiology in patients younger than 75 years of age, the calculated probability of active cancer was 53%.11 Although stroke patterns and territory involvement are not part of these criteria, our findings suggest patients with the TTS should be considered for underlying malignancy, and suggest malignancy-associated hypercoagulation as the etiology of stroke in patients with known cancer. More recently, D-dimer has been noted to be elevated in 75% of patients with cancer-associated ischemic stroke and exceeding 2.785 ug/mL in approximately 50% of these patients.12 The authors also noted the occurrence of 3 or more territory strokes as a characteristic of identifying cancer-associated stroke patients. The number of stroke territories, however, allowed infarcts of the same hemisphere to be counted as additional infarct territories. This is distinctly different from our criteria, where regardless of the number of infarcts, each anterior circulation hemisphere may only be counted as 1 territory. As such, the criteria for 3 territories as defined in our study are more stringent for patient selection.

Earlier studies site nonbacterial thromboembolism (NBTE) as the most frequent cause of symptomatic infarction on autopsy in patients with malignant tumor with stroke accounting for 27% of patients.1 However, no DWI-MRI was completed at that time to identify the importance of acute stroke patterns in those patients. More recent studies of stroke incidence in patients with cancer and stroke subtypes by TOAST criteria in conjunction with CT imaging or MRI found only 3% of patients with “embolic-appearing” stroke to have NBTE.13 In our study, none of the patients with the TTS had a cardioembolic source on echocardiography, supporting local intravascular hypercoagulability (Trousseau syndrome) as the underlying pathophysiology for the TTS in patients with malignancy as compared to NBTE. However, given the retrospective nature of the study, variability between techniques for valvular abnormality detection (transesophageal vs transthoracic echocardiography) was observed.

Patients with malignancy-related ischemic infarction have been historically treated with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). More recently, observational studies investigating novel oral anticoagulants in patients with cryptogenic stroke and active cancer have found no major difference in clinical outcomes and safety as compared to LMWH.14 Only 1 randomized trial investigated antiplatelet therapy as compared to LMWH for this subset of patients. However, because of the low number of patients and difficulty in recruitment, only 20 patients were randomized in this fashion and the study was underpowered to reach any conclusions regarding best therapy.15 Of interest, none of these studies in particular distinguished the effects of treatments in patients with NBTE as compared to intravascular hypercoagulability, and perhaps future treatment may need to differ if patients with imaging and echocardiography findings distinguish these subtypes.

We acknowledge that our study represents a single-center experience, evaluated a total of only 231 patients over 2 years, and that malignancy-related infarctions represent a small subset of all ischemic stroke etiologies. However, multiple territory infarctions are not infrequently encountered and with a significant proportion of patients with ESUS. The purpose of this study is to highlight the necessity of considering malignancy in the differential diagnosis for patients with the TTS, particularly when the etiology is unknown and the workup is completed.

Limitations

Given the retrospective nature of this study, several limitations are worth mentioning. Serum D-dimer levels were not routinely evaluated and therefore were not available for analysis. Although a marker of hypercoagulability, the mechanism associated with the hypercoagulable state in malignancy is complex and involves multiple mechanisms including activation of cell adhesion molecules by mucin secreted from adenocarcinomas, release of tissue factors by cancer cells causing activation of factor VII and X, endothelial cell damage from procoagulant cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1, and IL-6, causing vWF release, platelet activation, protein C inhibition, intravascular lymphomatosis, and increased viscosity observed in myeloproliferative disorders.5 Moreover, a drawback to this marker is low-specificity and elevation in many other conditions that include ischemic stroke itself.16 We acknowledge, however, it would be of value in addition to the radiologic findings. Data regarding extended heart monitoring for patients with the TTS and details regarding cancer activity including stage and treatment were not available. Both data elements are valuable in determining the hypercoagulable state and excluding confounders. We focused on the TTS as a pattern to be most indicative of the underlying stroke mechanism, being related to hypercoagulability, given that patients with malignancy also have 1- and 2-territory patterns and we did not attribute these to the condition. It is our hypothesis that perhaps this pattern supports the underlying malignancy actively producing a hypercoagulable state. Prospective data collection, however, would help prove this theory and evaluate stroke as a presenting feature of malignancy in this population. Finally, patients with both atrial fibrillation and malignancy were excluded from this study based on chart review. Although needed to eliminate bias and accurately determine significance of the TTS in each group, limitations attributed to the retrospective nature of the study are noted.

Conclusion

In patients with acute ischemic stroke and the TTS, occult malignancy should be considered a leading underlying mechanism and part of the ischemic stroke workup along with potential other causes, particularly when no clear etiology is defined. The TTS is far more frequently observed in patients with malignancy as compared to occult atrial fibrillation. In patients with malignancy, the TTS suggests a hypercoagulable state and Trousseau syndrome should be considered in secondary prevention.

Appendix. Author contributions

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ The MRI-DWI pattern in ischemic stroke should be considered important when evaluating stroke etiology.

→ Patients with the TTS with no known etiology may benefit from a malignancy workup in the absence of any identifiable cause including atrial fibrillation.

→ Recognition of this sign should include malignancy and Trousseau syndrome when observed on imaging by a radiologist and neurologist alike.

References

- 1.Graus F, Rogers LR, Posner JB. Cerebrovascular complications in patients with cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:16–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taccone FS, Jeangette SM, Blecic SA. First-ever stroke as initial presentation of systemic cancer. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;17:169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang DW, Chalela JA, Ezzeddine MA, Warach S. Association of ischemic lesion patterns on early diffusion-weighted imaging with TOAST stroke subtypes. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1730–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhadramy O, Jeerakathil TJ, Majumdar SR, Najjar E, Choy J, Saqqur M. Prevalence and predictors of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on Holter monitor in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2010;41:2596–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nouh A, Hussain M, Mehta T, Yaghi S. Embolic strokes of unknown source and cryptogenic stroke: implications in clinical practice. Front Neurology 2016;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grisold W, Oberndorfer S, Struhal W. Stroke and cancer: a review. Acta Neurol Scand 2009;119:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Zeng J, Xie X, Wang Z, Wang X, Liang Z. Clinical features of systemic cancer patients with acute cerebral infarction and its underlying pathogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:4455–4463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finelli PF, Nouh A. Three-territory DWI acute infarcts: diagnostic value in cancer-associated hypercoagulation stroke (Trousseau syndrome). Am J Neuroradiology 2016;37:2033–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varki A. Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood 2007. 110:1723–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SG, Hong JM, Kim HY, et al. Ischemic stroke in cancer patients with and without conventional mechanisms: a multicenter study in Korea. Stroke 2010;41:798–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvik HA, Bjerkreim AT, Thomassen L, Waje-Andreassen U, Naess H, Kvistad CE. When to screen ischaemic stroke patients for cancer. Cerebrovasc Dis 2018;45:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JY, Zhang GJ, Zhuo SX, et al. D-dimer> 2.785 μg/ml and multiple infarcts≥ 3 vascular territories are two characteristics of identifying cancer-associated ischemic stroke patients. Neurol Res 2018;40:948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cestari DM, Weine DM, Panageas KS, Segal AZ, DeAngelis LM. Stroke in patients with cancer: incidence and etiology. Neurology 2004;62:2025–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nam KW, Kim CK, Kim TJ, et al. Treatment of cryptogenic stroke with active cancer with a new oral anticoagulant. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017;26:2976–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navi BB, Marshall RS, Bobrow D, et al. Enoxaparin vs aspirin in patients with cancer and ischemic stroke: the TEACH pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lippi G, Bonfanti L, Saccenti C, Cervellin G. Causes of elevated D-dimer in patients admitted to a large urban emergency department. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.