Abstract

Introduction

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) displays variable progression trajectories that require further elucidation.

Methods

Longitudinal quantitation of atrophy and language over 12 months was completed for PPA patients with and without positive amyloid PET (PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ−), an imaging biomarker of underlying Alzheimer’s disease.

Results

Over 12 months, both PPA groups showed significantly greater cortical atrophy rates in the left versus right hemisphere, with a more widespread pattern in PPAAβ+. The PPAAβ− group also showed greater decline in performance on most language tasks. There was no obligatory relationship between the logopenic PPA variant and amyloid status. Effect sizes from quantitative MRI data were more robust than neuropsychological metrics.

Discussion

Preferential language network neurodegeneration is present in PPA irrespective of amyloid status. Clinical and anatomical progression appears to differ for PPA due to Alzheimer’s disease versus non–Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, a distinction that may help to inform prognosis and the design of intervention trials.

Keywords: Frontotemporal dementia, Primary progressive aphasia, Volumetric MRI, FreeSurfer, Neuropsychology, Biomarker, Amyloid PET, Progression, Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

1. Introduction

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a clinical dementia syndrome defined by deterioration of language functions over time and initial relative sparing of other cognitive domains [1]. It is associated with two main classes of neuropathology: frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In vivo biomarkers such as amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) are emerging and hold promise for determining contributing underlying neuropathology during life. Thus far, amyloid PET biomarker studies in PPA have shown good reliability for detection of underlying pathology and reinforced the notion that relationships between clinical subtypes (agrammatic [PPA-G], semantic [PPA-S], and logo-penic [PPA-L] [2,3]) and underlying neuropathology are probabilistic rather than deterministic [4–7].

Determinants of the pace of decline in PPA are incompletely understood, especially whether the presence of AD versus non-AD pathology influences the rate of deterioration. This is in part because of a dearth of prospective longitudinal investigations [8–14] relative to cross-sectional investigations and the historic lack of in vivo neuropathologic biomarkers. Disease duration estimates for individuals with PPA range from 3 to 20 years, highlighting the individual variability in progression rates. Some data suggest that those with FTLD neuropathology may progress more rapidly than those with AD neuropathology [9], but these data are relatively sparse.

This prospectively designed study assessed whether cortical and neuropsychological change could be detected at 6-month intervals in non–semantic PPA participants with and without elevated amyloid PET. Of particular interest was determining whether atrophy rates differed for PPA patients with suspected AD versus non-AD neuropathologic change and whether progressive atrophy remained left lateralized over time. It expands the existing literature by offering a prospective design, examining clinical and imaging decline at relatively short 6-month intervals, and stratifying by suspected underlying pathology with robust imaging biomarkers. Understanding the biological factors influencing the rate of decline is essential for uncovering mechanisms underlying clinical expression, designing intervention targets and outcomes, and developing care plans for individuals living with PPA.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from 2012 to 2016 into Northwestern University’s PPA Research Program for a prospective study examining disease progression at 6-month intervals. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Participants were required to be right-handed and meet root PPA diagnostic criteria, namely, an initially isolated and progressive language impairment due to neurodegenerative disease [15–17]. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed for each participant by a behavioral neurologist (M.M.M.). Clinical subtypes were assigned according to previously established research guidelines [16]. Participants presenting with single-word retrieval and repetition impairments along with relative sparing of word comprehension were classified as PPA-L. Participants presenting with a salient grammatical impairment, effortful speech, and relative preservation of word comprehension were classified as PPA-G. Participants with mild-to-moderate non–semantic PPA (i.e., PPA-G or PPA-L variants), with a Western Aphasia Battery [18] Aphasia Quotient (WAB-AQ) score of ≥65 at their initial visit were included.

Participants were required to have amyloid PET imaging with 18F-florbetapir at a single time point to determine biomarker status and longitudinal MR and neuropsychological testing at 6-month intervals over the course of 12 months. All PPA participants completed three MR imaging visits (initial, 6-months, and 12 months).

Twenty-five community dwelling cognitively healthy controls of similar age and education level with MR imaging at a single time point were used as a comparison group for some of the MRI analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for the PPAAβ+, PPAAβ−, and control groups

| PPAAβ+ | PPAAβ− | NC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 17 | 9 | 25 |

| Age at initial visit | 66.3 (5.8) [58–80] | 70.8 (7.2) [61–82] | 67.8 (5.8) [60–80] |

| Gender (% M) | 8 (47%) | 5 (56%) | 14 (56%) |

| Education | 16.4 (2.4) [12–20] | 15.0 (2.2) [12–19] | 16.1 (2.4) [11–20] |

| Initial visit symptom duration | 5.2 (2.8) [1.4–10.9] | 3.9 (1.3) [2.1–6.0] | – |

| Months between visits | 6.3 (0.5) [5.5–7.6] | 6.1 (0.3) [5.2–6.7] | – |

| Subtype | |||

| Logopenic | 10 (59%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Agrammatic | 7 (41%) | 7 (78%) | |

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

NOTE. Numbers are provided as means, (standard deviations), and [Ranges]. Education and symptom duration are provided in years. Months between visits are provided as the average number of months between initial visit and 6-month visit and 6-month visit and 12-month visit. There were no significant differences in demographics among the groups.

2.2. Neuropsychological measures

2.2.1. Language domains

The WAB-AQ [18] measured aphasia severity based on auditory comprehension, naming, repetition, and spontaneous speech. Grammatical processing was measured using 15 noncanonical sentence items from the Northwestern Anagram Test [19]. Moderately difficult items from the fourth edition of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test [20] were used as a measure of lexical-semantic processing. Naming ability was assessed with the Boston Naming Test [21]. Repetition was quantified using the six most difficult items from the WAB-Repetition Subtest [22].

2.2.2. Non-language domains

Initial presence of deficits in memory, comportment, and/ or visuospatial abilities precludes a PPA diagnosis but can emerge over time. These domains were deemed to be intact at the initial visit by formal test scores, informant report, and/or clinician assessment by an expert behavioral neurologist (M.M.M). Presence of motor-speech impairments was assessed based on clinical impression and/or apraxia of speech measures. Global measures of functioning included the activities of daily living questionnaire and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale [23–25].

2.3. Imaging acquisition

T1-weighted 3D MP-RAGE sequences (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.91 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, FoV = 256 mm), recording 176 slices at a slice thickness of 1.0 mm, were acquired on a 3T Siemens TIM Trio using a 12-channel birdcage head coil.

PET imaging for the PPA group was performed on a Siemens Biograph 40 TruePoint/TrueV PET-CT system. A computed tomography scan was acquired for attenuation correction followed by a 20-min dynamic PET acquisition 50 minutes after administration of 370 MBq 18F-florbetapir.

2.4. Biomarker status

A board-certified nuclear medicine physician (author, A.K.A.) completed a visual read of each florbetapir PET scan to determine if uptake was elevated (Aβ+) or not (Aβ−) [26]. Briefly, individuals were considered Aβ+ if there was increased retention of the tracer in the cortical gray matter, defined as either loss of gray-white contrast in at least two cortical regions or, as intense, focal uptake in at least one cortical region. The PET scan was considered Aβ− when there was preserved gray/white contrast throughout the cortex or loss of gray/contrast was isolated to one region only. This method showed strong test-retest reliability [27], and in an autopsy study, the visual reads were slightly more reliable than the quantitative reads [26]. Visual reads are also important because previous reports [28,29] suggest PPAAβ+ individuals can show focal, asymmetric uptake (left > right), which may not be detected by the standard volumes of interest developed and tested in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type due to AD [27].

2.5. Cortical thickness and volume measurements

MR images were processed using the cross-sectional [30] and longitudinal [31] pipelines from FreeSurfer (v5.1.0). Topological surface errors were corrected by manual intervention according to established guidelines [32] in an iterative fashion until completely resolved. Cortical thickness estimates were calculated by measuring surface distances between representations of the white-gray and pial– cerebrospinal fluid boundaries.

Whole-brain vertex-wise cortical thickness analyses were used to identify differences between groups at single time points and within each group across time points. Vertex-wise Cohen’s d cortical thickness effect-size maps were generated to supplement the significance comparisons.

In addition to whole-brain vertex-wise cortical thickness analysis, two bilateral a priori regions of interest (ROIs) described in our previous longitudinal study [13] were used: (1) a cortex ROI of the entire neocortical surface, which served as a global measure of atrophy for each hemisphere [33], and (2) a revised language network ROI defined for the perisylvian cortex (PSTCR), which was identical to the previously described [13] PSTC ROI except that the insula was excluded in the revised version to provide a focal cortical language network ROI.

Estimates of cortical gray matter volume were extracted from the subject native space for the two bilateral ROIs. The volumetric estimates (ROInative) were adjusted for head size using the estimated total intracranial volume (eTIVnative) calculated from the unbiased within-subject template [34]. Normalized volume (ROInormalized) at each visit was calculated as follows:

where fsaverage is FreeSurfer’s MNI-space brain template (eTIVfsaverage = 1,948,106 mm3).

Volume loss was calculated as the percent change in volume over 6- and 12-month intervals as follows:

Visit A is chronologically earlier.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Measures included demographics, clinical information, cortical thickness, ROI volume, and neuropsychological tests. PPAAβ+, PPAAβ−, and control data were compared using analysis of variance, t-tests, or Fisher’s exact tests.

Vertex-wise cortical thickness between-group differences were calculated by conducting a general linear model across every vertex along the cortical surface, derived from structural MR data processed with FreeSurfer. Within-group longitudinal vertex-wise analyses were conducted using paired t-tests along the cortical surface using a false discovery rate of 0.05 [35].

Volume was analyzed using a mixed linear model with percent change as the dependent variable and amyloid status, hemisphere, and their interaction as covariates. This model accounted for repeated measures (left hemisphere [LH] and right hemisphere [RH] of the same person) and an unstructured covariance pattern. Two post hoc t-tests were used to compare hemispheres by amyloid status and two tests compared rates of change (PPAAβ+ vs. PPAAβ−) by hemisphere. Change over 12 months for the four hemisphere/amyloid subgroups was compared to zero using a t-test from the model. Bonferroni corrected significance was declared if P < .0125 (0.05/4 for 2 sets of 4 tests). Separate analyses were done for cortex and PSTCR.

Seven neuropsychological tests were analyzed using a mixed linear model with amyloid status as the between-subjects factor. To test whether there was significant change over time within each group, or to compare percent change in test scores between groups, Bonferroni corrected significance was declared if P <.0071 (0.05/7 for 3 sets of 7 tests).

Univariate linear regression was used to relate baseline cortical volume to 12-month percent change in cortex or PSTCR volume stratified by hemisphere. This process was repeated for baseline WAB-AQ (%). For these models, statistical significance was declared if P <.05.

3. Results

There were no differences in demographics among the groups (Table 1). The PPA-G participants were equally distributed between the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups, whereas the PPA-L participants tended to be in the PPAAβ+ group.

3.1. Initial vertex-wise patterns of atrophy

Vertex-wise thickness analyses across the cortex were used to identify peak areas of atrophy at the initial visit of the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups relative to cognitively healthy controls. Consistent with previous reports [4,36], both the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups showed asymmetric atrophy (LH > RH) most prominently located in the language network at the initial visit (Fig. 1A). The pattern of atrophy at the initial visit was more pronounced and widespread in the PPAAβ+ than PPAAβ− group. Compared with controls, peak LH atrophy on the lateral surface in the PPAAβ+ group included the temporoparietal junction, the inferior frontal gyrus, superior and caudal middle frontal gyri, fusiform, as well as the superior middle and inferior temporal gyri including the temporal pole. Peak atrophy in the PPAAβ− group was primarily in left perisylvian regions including the posterior inferior frontal gyrus, the superior temporal gyrus, and anterior portions of the middle temporal gyrus and inferior temporal gyrus.

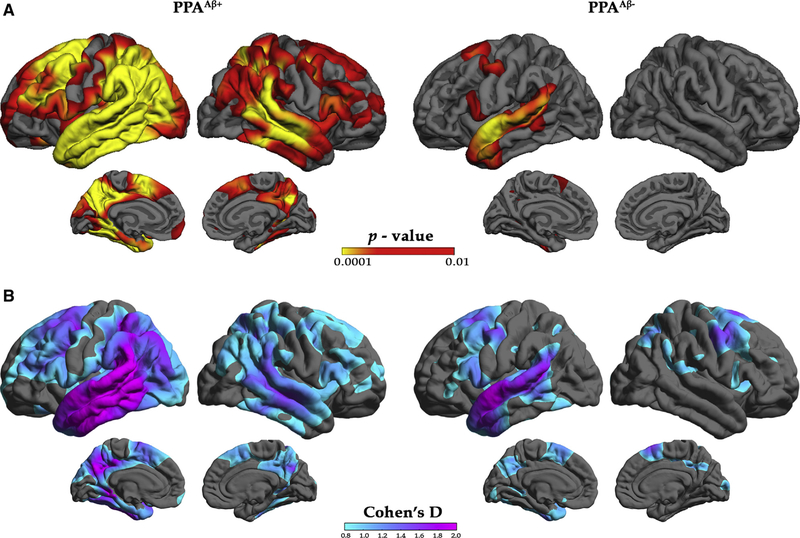

Fig. 1.

Characterization of cortical atrophy at initial visit for the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups. (A) Vertex-based cortical atrophy patterns by amyloid status at the initial visit. Left: Red/yellow indicates significant cortical thinning patterns for the PPAAβ+ participants relative to controls. Right: Red/yellow indicates significant cortical thinning patterns for the PPAAβ− participants relative to controls. The false discovery rate was set at 0.05 for each comparison. (B) Cohn’s d effect-size maps by amyloid status at initial visit based on standard deviation for the PPAAβ+ (left) and PPAAβ− (right) participants. Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

There was significant atrophy in the RH of the PPAAβ+ group, which was absent in the PPAAβ− group. RH atrophy in the PPAAβ+ group was more intense in the temporoparietal junction, superior temporal gyrus, and middle temporal gyrus.

Because the PPAAβ+ group was nearly twice the size of the PPAAβ−, it is possible that group differences in atrophy patterns were driven by sample size. To explore this possibility, effect sizes were examined. Effect size maps largely mirrored atrophy maps, confirming leftward asymmetry of atrophy in both groups and more extensive atrophy in the PPAAβ+ group (Fig. 1B).

3.2. Vertex-wise progression of atrophy

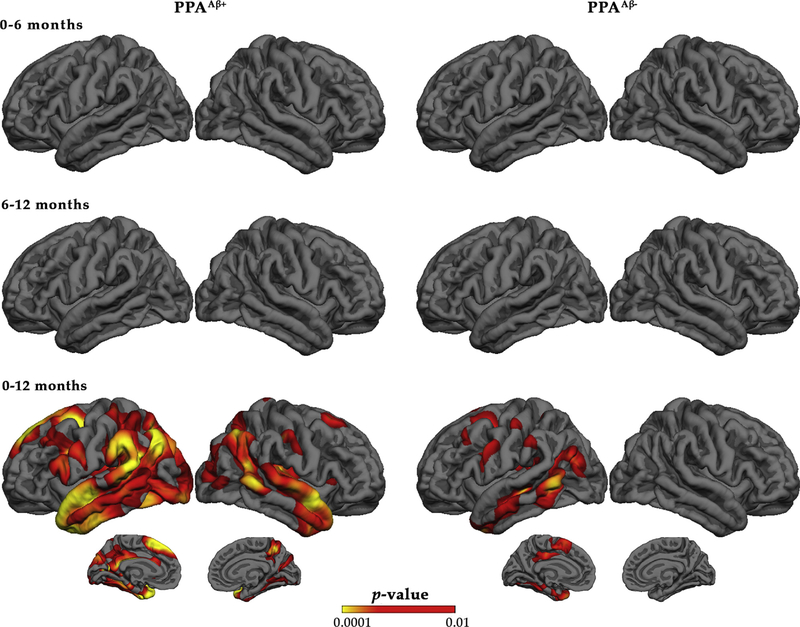

Vertex-based percent change in thickness was examined at each 6-month visit interval (0–6 months and 6–12 months) and also over 12 months for each group (Fig. 2). For each group, percent change in atrophy was significant over 12 months but not at 6-month intervals. Twelve-month percent change in atrophy showed leftward asymmetry for both groups. However, the percent change in atrophy was more extensive in the PPAAβ+ group including the inferior frontal gyrus, temporoparietal junction, and temporal regions of the LH with RH change mainly occurring in homologous regions. Percent change in atrophy for the PPAAβ− group was restricted to the LH, primarily in the middle temporal gyrus.

Fig. 2.

Vertex-based percent change in cortical thickness by amyloid status. Red/yellow indicates significant cortical thinning patterns. The false discovery rate was set at 0.05 for each comparison. Abbreviation: PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

3.3. ROI progression of atrophy

Because the percent change in volume and thickness was negligible at 6-month intervals, the ROI analysis focused on the 0-to-12-month interval. Percent change in volume for the cortex and PSTCR ROIs was examined over a 12-month interval to determine if progression of atrophy (1) was significant for the LH and RH ROIs; (2) was asymmetric; and (3) had different rates between the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups.

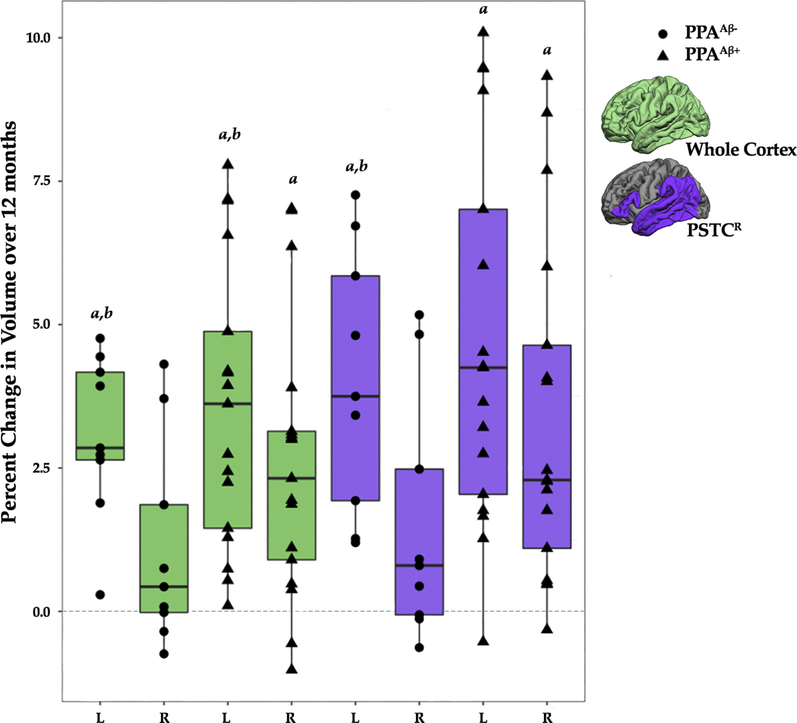

In the PPAAβ+, percent change in volume over 12 months was significantly different from zero for the cortex and PSTCR ROIs for both the LH and RH (mean ± SEM for cortex: LH, 3.59 ± 0.53; RH, 2.59 ± 0.54; PSTCR: LH, 4.71 ± 0.73; RH, 3.39 ± 0.66, P values ≤ .0125; Fig. 3). In the PPAAβ− group, percent change in atrophy was significantly different from zero for the LH cortex and PSTCR ROIs but not the RH ROI (mean ± SEM for cortex: LH, 3.08 ± 0.73; RH, 1.11 ± 0.75; PSTCR: LH, 4.03 ± 1.00; RH, 1.53 ± 0.91; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percent change over 12 months by hemisphere, amyloid status, and ROI. aPercent change in volume was significantly different from zero (P <.0125). bPercent change in volume was significantly greater in the left hemisphere than the right hemisphere (P <.0071). The middle, upper, and lower horizontal lines in the box plot represent the median, 75th, and 25th percentiles, respectively. The end of the vertical extensions above and below the box represent the extreme value that is at most 1.5 times the interquartile range above the 75th percentile or below the 25th percentile. Abbreviations: PPA, primary progressive aphasia; PSTCR, revised language network ROI defined for the perisylvian cortex; ROI, region of interest.

For both groups, percent change in volume for the cortex ROI over 12 months was greater in the LH than the RH (P values ≤ .0071; Fig. 3), which is consistent with the vertex-wise cortical thinning patterns (Fig. 2). Percent change in volume for the PSTCR ROI was significantly greater for the LH than the RH for the PPAAβ− group (P = .0071) but did not survive correction for the PPAAβ+ group (P = .04; Fig. 3).

There was no significant difference between the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups in the percent change in volume of the cortex or PSTCR ROI by hemisphere over 12 months (Fig. 3).

3.4. Language performance measures

Similar to the imaging metrics, decline was small and variable for the language performance measures at 6-month intervals; therefore, analysis focused on the 0-to-12-month interval (Table 2). Decline in scores was evident for all but two participants over 12 months, though there was variability in decline at the individual level by test.

Table 2.

Scores on neuropsychological tests of language and an activities of daily living questionnaire at initial and 12-month visits by group

| PPAAβ+, (n = 17)* | PPAAβ−, (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|

| WAB-AQ | ||

| Initial visit | 84.2 (0.02) [67.8–96.8] | 83.8 (0.03) [71.7–93.6] |

| 12-month visit | 75.4 (0.03) [29.0–94.6] | 78.3 (0.04) [62.8–87.4] |

| % Change over 12 months | 11.0 (2.72)† | 6.7 (3.74) |

| BNT | ||

| Initial visit | 69.4 (0.06) [21.7–96.7] | 77.4 (0.07) [25.0–93.3] |

| 12-month visit | 55.1 (0.07) [13.3–98.3] | 69.3 (0.09) [13.3–91.7] |

| % Change over 12 months | 24.5 (4.57)† | 13.6 (6.09) |

| Grammar (NATnc) | ||

| Initial visit | 65.3 (0.05) [33.3–93.3] | 63.0 (0.07) [26.7–100.0] |

| 12-month visit | 66.2 (0.06) [33.3–100.0] | 51.1 (0.07) [13.3–80.0] |

| % Change over 12 months | −1.9 (8.55) | 12.7 (11.04) |

| WAB Rep 66 | ||

| Initial visit | 66.8 (0.04) [36.4–97.0] | 74.4 (0.05) [50.0–93.9] |

| 12-month visit | 59.4 (0.04) [24.2–89.4] | 66.3 (0.06) [45.5–90.9] |

| % Change over 12 months | 10.1 (4.82) | 11.3 (6.63) |

| PPVT | ||

| Initial Visit | 93.8 (0.01) [80.6–100.0] | 94.1 (0.02) [88.9–100.0] |

| 12-month visit | 87.9 (0.03) [55.6–100.0] | 92.3 (0.04) [83.3–100.0] |

| % Change over 12 months | 6.6 (2.18)† | 2.0 (3.00) |

| CDR-Global‡ | ||

| Initial visit no. 0/0.5/1/2 | 4/11/2/0 | 6/3/0/0 |

| 12-month visit no. 0/0.5/1/2 | 3/11/1/2 | 4/5/0/0 |

| CDR-Language‡ | ||

| Initial visit no. 0/0.5/1/2 | 0/5/7/5 | 0/1/6/2 |

| 12-month visit no. 0/0.5/1/2 | 0/2/9/6 | 0/2/4/3 |

| ADLQ‡ | ||

| Initial visit no. Mild/Moderate/Severe | 15/2/0 | 9/0/0 |

| 12-month visit no. Mild/Moderate/Severe | 10/7/0 | 9/0/0 |

Abbreviations:WAB-AQ, Western Aphasia Battery-Aphasia Quotient; BNT, Boston Naming Test; NATnc, noncanonical items on the Northwestern Anagram Test; WAB Rep 66, items 10–15 on the Western Aphasia Battery Repetition Subtest; PPVT, a subset of moderately difficult items (items 157–192) from the fourth edition of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; ADLQ, activities of daily living questionnaire; PPA, primary progressive aphasia.

NOTE. Numbers are provided as means, (standard errors), and [Ranges]. Average percent correct (standard error), [range], and percent change over 12 months are provided by group.

NOTE. The ADLQ is an informant-rated survey of functional impairments. On the ADLQ, functional impairment is rated as none to mild (0%-33%), moderate (34%-66%), or severe (67%-100%). Analysis focused on the percent change over 12 months.

Data for the BNT were not available for one PPAAβ+ participant. NATnc data were not available for two PPAAβ+ participants.

Indicates significant (P <.0071) decline (relative to zero) within-group as measured by percent change over 12 months.

Tests were not performed because of zero frequencies and very small numbers in some categories.

The PPAAβ+ group showed decline on WAB-AQ, Boston Naming Test, and Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test scores (P values ≤ .0071), whereas the PPAAβ− group did not. There were no differences in the percent change in decline over 12 months on language performance measures between the groups. Presence of motor-speech difficulties was similar between the PPAAβ+ (n = 6) and PPAAβ− (n = 5) groups.

3.5. Identifying relationships between language performance and atrophy

First, we examined whether initial visit severity predicted percent change in atrophy. Initial severity was queried anatomically by quantifying initial cortical volume while initial WAB-AQ was used as a general measure of aphasia severity. There were no significant relationships between initial cortical volume and 12-month percent change in cortex volume or in PSTCR volume for each hemisphere (P values > .05). Likewise, there were no significant associations between initial WAB-AQ score and 12-month percent change in cortex or in PSTCR volume for each hemisphere (P values > .05).

Previous research suggests that neuroimaging measures provide more efficient measures of change than neuropsychological measures. Effect sizes for percent change measurements over 12 months were greater for the LH cortex and LH PSTCR volume metrics (effect size range: 1.43–2.03) than for the WAB-AQ and Boston Naming Test language performance measures (effect size range: 0.84–1.35) for the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups.

4. Discussion

This study characterized the pace and pattern of atrophy over 1 year in PPA participants with suspect AD versus non-AD neuropathologic change. Although atrophy was greater in the LH for both groups, quantitative measurements showed a more widespread pattern of atrophy in the PPAAβ+ than the PPAAβ− group. These data suggest there may be an important interaction between disease-specific proteinopathy and selective vulnerability that drives distribution and progression of disease.

The more diffuse distribution of atrophy in the PPAAβ+ group may have implications for the tempo of clinical progression, including the earlier emergence of non-language symptoms potentially accompanied by declines in activities of daily living. This study did not focus on precise quantitation of non-language domains; however, activities of daily living questionnaire and Clinical Dementia Rating tended to be more severe in the PPAAβ+ group over the 12-month interval.

Individuals with the PPA-L variant were found in both the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups, which is consistent with previous studies showing there is no one-to-one relationship between clinical phenotype and underlying pathology [4,7,37]. Thus, using PPA-L as a surrogate for determining underlying pathology remains probabilistic and insufficient at the individual level.

Longitudinal studies of neuroanatomical change in PPA are relatively uncommon [11–14,38–42]. Many studies have focused on large-scale measurements of whole-brain volume, ventricular volume, or cortical volume. The present study used both vertex-based measurements of cortical thickness as well as targeted (PSTCR) and global (cortex) ROI measurements. Vertex-wise analyses provide unbiased visual representations of the anatomical patterns of change across the cortex, which adds to the understanding of the natural progression of the disease by suspected neuropathology. ROI analyses provide a common quantitative currency for comparing progression among groups and hold potential as outcome metrics for clinical trials.

Effect size results are consistent with previous reports suggesting that structural MR metrics provide more robust measures of change than cognitive performance measures [11,13,43]. Thus, cortical ROI measures such as the PSTCR may be useful for future clinical trials and may allow for smaller sample sizes to detect a significant effect. Intriguing summary scores of language performance are emerging [10] and may be useful to detect change as they are optimized. Understanding consistency of these measures at the individual level over the disease course is important before they can be reliably introduced as clinical trial outcome metrics.

There was no simple linear relationship between initial volume and percent change over the relatively short 12-month interval. One potential hypothesis is that individuals with the smallest baseline volume would show the slowest rate of progression over time, in part, because there is less brain mass to lose. Our results did not support this conclusion. Percent change in volume did not show a significant correlation with initial volume or aphasia severity.

One potential limitation was reliance on florbetapir-PET as the AD biomarker in this study. Sensitivity and specificity are high for florbetapir (>95%) in individuals who were scanned 1 year before death [44]. PPA participants with elevated amyloid scans could have additional FTLD or TAR DNA-binding protein 43 pathology. However, data from our previous report suggest this likelihood is low because only one of 58 consecutive PPA autopsies showed a double diagnosis [5]. Five participants in this study have come to autopsy, and their florbetapir status was concordant with their neuropathologic diagnosis (i.e., three PPAAβ+ participants had changes consistent with AD and two PPAAβ−, one with FTLD-tau [progressive supranuclear palsy] and one with FTLD-tau [Pick]). These results reinforce the possibility of including PPAAβ+ individuals in clinical trials targeting the AD pathophysiologic process.

Clinical trials targeting the AD pathophysiological process are underway. Trial-ready dementia cohorts are emerging from multicenter projects and registries. AD biomarker-positive PPA patients are appropriate for AD therapeutic trials but are rarely included. The lack of clarity around appropriate outcome metrics and poor understanding of individual variability may be influencing their exclusion. Past PPA trials have been handicapped by the inability to align participants into trials based on likely underlying neuropathology. Judicious use of in vivo biomarkers provides an opportunity to advocate for the inclusion of atypical forms of AD into clinical trials.

Preferential neurodegeneration of the LH language network is a common denominator for both the PPAAβ+ and PPAAβ− groups, even as the disease progresses. These data suggest disease-specific proteinopathy may be one factor influencing the rate and cortical distribution of atrophy. However, individual variability was also present. Factors influencing the rate of atrophy and clinical progression at the individual level remain elusive and require additional investigation.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: The existing literature was reviewed (e.g., PubMed) and cited. These investigations report variable disease duration for those with primary progressive aphasia (3–20 years) with few prospective studies assessing the biological factors influencing rate of decline.

Interpretation: Preferential neurodegeneration of the language network is a common feature in primary progressive aphasia irrespective of suspected underlying pathology, even as the disease progresses. However, the nature of clinical and anatomical progression appears to differ for those with primary progressive aphasia with suspected Alzheimer versus non-Alzheimer neuropathology.

Future directions: Although proteinopathy may be one factor influencing the rate of atrophy and clinical progression, additional factors remain elusive and require additional investigation. These results reinforce the need for reliable biomarkers and prospective studies of biological progression which are necessary for uncovering mechanisms underlying clinical expression, designing intervention targets and outcomes, and developing care plans for individuals with aphasic forms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christina Coventry, Emmaleigh Loyer, Marie Saxon, Amanda Rezutek, Maureen Connelly, Danielle Barkema, and Kristen Whitney for neuropsychological test administration of the participants and Allison Rainford for her assistance with FreeSurfer MR processing. MR Imaging was performed at the Northwestern University Department of Radiology Center for Translational Imaging (CTI). PET Imaging was performed at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. The authors thank Avid Radiopharmaceuticals for the amyloid PET doses for this study.

Study Funding: This project was supported in part by DC008552 from the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders; AG13854 (Alzheimer Disease Core Center) and AG056258 from the National Institute on Aging; and NS075075 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

A.M., B.R., J.S., A.J.F., and A.R. have nothing to disclose. Drs. Bigio, Weintraub, Cobia, Mesulam, and Rogalski report grants from NIH during the conduct of the study. 18F-florbetapir doses were provided as nonfinancial support by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (awarded to E.R.). Dr. Arora is an employee of Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

References

- [1].Mesulam MM. Primary Progressive Aphasia: A Language-Based Dementia. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol 2004;55:335–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mesulam M, Wieneke C, Rogalski E, Cobia D, Thompson C, Weintraub S. Quantitative template for subtyping primary progressive aphasia. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rogalski E, Sridhar J, Rader B, Martersteck A, Chen K, Cobia D, et al. Aphasic variant of Alzheimer disease: Clinical, anatomic, and genetic features. Neurology 2016;87:1337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, Bigio EH. Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain 2014; 137:1176–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Oboudiyat C, Gefen T, Varelas E, Weintraub S, Rogalski E, Bigio EH, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers detect Alzheimer’s disease in non-amnestic dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:598–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Teichmann M, Kas A, Boutet C, Ferrieux S, Nogues M, Samri D, et al. Deciphering logopenic primary progressive aphasia: a clinical, imaging and biomarker investigation. Brain 2013;136:3474–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Binney RJ, Pankov A, Marx G, He X, McKenna F, Staffaroni AM, et al. Data-driven regions of interest for longitudinal change in three variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain Behav 2017; 7:e00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, Slama H, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, et al. Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2005;65:719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Semler E, Anderl-Straub S, Uttner I, Diehl-Schmid J, Danek A, Einsiedler B, et al. A language-based sum score for the course and therapeutic intervention in primary progressive aphasia. Alzheimer’s Res Ther 2018;10:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr, Kramer JH, Boeve BF, Caselli RJ, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Brain and ventricular volumetric changes in fronto-temporal lobar degeneration over 1 year. Neurology 2009;72:1843–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rohrer JD, Caso F, Mahoney C, Henry M, Rosen HJ, Rabinovici G, et al. Patterns of longitudinal brain atrophy in the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang 2013;127:121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rogalski E, Cobia D, Martersteck A, Rademaker A, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, et al. Asymmetry of cortical decline in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2014;83:1184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, Mesulam MM. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2011; 76:1804–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mesulam M, Weintraub S. Primary progressive aphasia and kindred disorders. Handb Clin Neurol 2008;89:573–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011;76:1006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mesulam MM, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Hurley RS, Geula C, Bigio EH, et al. Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:554–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kertesz A Western Aphasia Battery. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, Rademaker A, Rogalski EJ, Thompson CK. The northwestern anagram test: measuring sentence production in primary progressive aphasia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2009;24:408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dunn L, Dunn D. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Assessment Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, Thompson C, Rogalski E, Weintraub S. Quantitative classification of primary progressive aphasia at early and mild impairment stages. Brain 2012;135:1537–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Johnson N, Barion A, Rademaker A, Rehkemper G, Weintraub S. The Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire: a validation study in patients with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2004;18:223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, Beach TG, Bilker WB, Mintun MA, et al. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA 2011;305:275–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Joshi AD, Pontecorvo MJ, Clark CM, Carpenter AP, Jennings DL, Sadowsky CH, et al. Performance characteristics of amyloid PET with florbetapir F 18 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal subjects. J Nucl Med 2012;53:378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Martersteck A, Murphy C, Rademaker A, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, Chen K, et al. Is in vivo amyloid distribution asymmetric in primary progressive aphasia? Ann Neurol 2016;79:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ng SY, Villemagne VL, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Evaluating atypical dementia syndromes using positron emission tomography with carbon 11 labeled Pittsburgh compound B. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 1999;9:179–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage 2012;61:1402–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Segonne F, Pacheco J, Fischl B. Geometrically accurate topology-correction of cortical surfaces using nonseparating loops. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007;26:518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006;31:968–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, Fotenos AF, Marcus D, Morris JC, et al. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: Reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage 2004;23:724–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage 2002;15:870–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rohrer JD, Rossor MN, Warren JD. Alzheimer’s pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33:744–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Giannini LAA, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Ash S, Rascovsky K, Wolk DA, et al. Clinical marker for Alzheimer disease pathology in logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neurology 2017;88:2276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Avants B, Anderson C, Grossman M, Gee JC. Spatiotemporal normalization for longitudinal analysis of gray matter atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2007; 10:303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Brambati SM, Rankin KP, Narvid J, Seeley WW, Dean D, Rosen HJ, et al. Atrophy progression in semantic dementia with asymmetric temporal involvement: a tensor-based morphometry study. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:103–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rohrer JD, Clarkson MJ, Kittus R, Rossor MN, Ourselin S, Warren JD, et al. Rates of hemispheric and lobar atrophy in the language variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 30:407–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Whitwell JL, Anderson VM, Scahill RI, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Longitudinal patterns of regional change on volumetric MRI in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;17:307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rohrer JD, McNaught E, Foster J, Clegg SL, Barnes J, Omar R, et al. Tracking progression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: serial MRI in semantic dementia. Neurology 2008;71:1445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Edland SD, Ard MC, Sridhar J, Cobia D, Martersteck A, Mesulam MM, et al. Proof of concept demonstration of optimal composite MRI endpoints for clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2016;2:177–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, Bedell BJ, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloidbeta plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11:669–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]