Abstract

To explore the possibility of constrained peptides to target Plasmodium-infected cells, we designed a J domain mimetic derived from Plasmodium falciparum calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (Pf CDPK1) as a strategy to disrupt J domain binding and inhibit Pf CDPK1 activity. The J domain disruptor (JDD) peptide was conformationally constrained using a hydrocarbon staple and was found to selectively permeate segmented schizonts and colocalize with intracellular merozoites in late-stage parasites. In vitro analyses demonstrated that JDD could effectively inhibit the catalytic activity of recombinant Pf CDPK1 in the low micromolar range. Treatment of late-stage parasites with JDD resulted in a significant decrease in parasite viability mediated by a blockage of merozoite invasion, consistent with a primary effect of Pf CDPK1 inhibition. To the best of our knowledge, this marks the first use of stapled peptides designed to specifically target a Plasmodium falciparum protein and demonstrates that stapled peptides may serve as useful tools for exploring potential antimalarial agents.

Keywords: stapled peptides, chemical probes, Plasmodium falciparum, antimalarial, calcium-dependent protein kinase 1

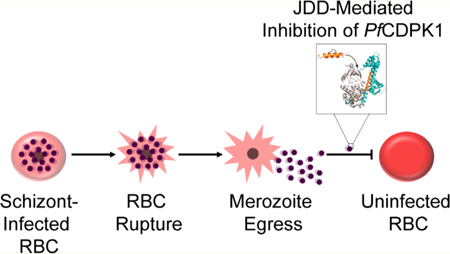

Graphical Abstract

Malaria parasites, belonging to the genus Plasmodium, are intracellular protozoan parasites endemic to 91 countries worldwide.1 Their continued transmission placed nearly half the world’s population at risk of malaria and led to an estimated 445,000 deaths in 2017 alone.1 Contrary to what such estimates might suggest, the global health community has made significant advances in malaria control over recent years, effectively reducing malaria mortality rates by 60% globally since 2000.2 Unfortunately, evidence of spreading resistance to antimalarial drugs places ongoing control efforts at risk.3–5 While a combinatorial approach, applying multiple drugs with varying mechanisms of action, has delayed the spread of resistance, future control efforts will rely on the development of innovative antimalarial drugs as well as the discovery and characterization of novel Plasmodium protein targets.

Although constrained peptides have not been extensively explored as inhibitors/modulators for malaria targets, we previously demonstrated that a constrained hydrocarbon-stapled peptide, STAD-2, which was designed to target the interface between the regulatory subunit of human protein kinase A (PKA-R) and A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), was selectively permeable to P. falciparum-infected red blood cells (iRBC) in vitro.6 STAD-2 localized within the intracellular parasite and demonstrated rapid antiplasmodial activity via a PKA-independent mechanism. On the basis of these findings, we chose to explore whether stapled peptides could be designed as probes to explore and characterize potential Plasmodium protein targets.

P. falciparum has a relatively small kinome composed of less than 100 identified kinases, a significant proportion of which have no mammalian ortholog.7,8 For example, the calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) are found in plants and alveolates but are altogether absent from metazoans.7 Such Plasmodium kinases may serve as ideal targets for probe design while minimizing impact on human host cell kinases. Further, such tools would be invaluable for investigating the roles of various malaria proteins throughout the parasite lifecycle. Herein, we focused on the well-studied Plasmodium falciparum calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (Pf CDPK1).

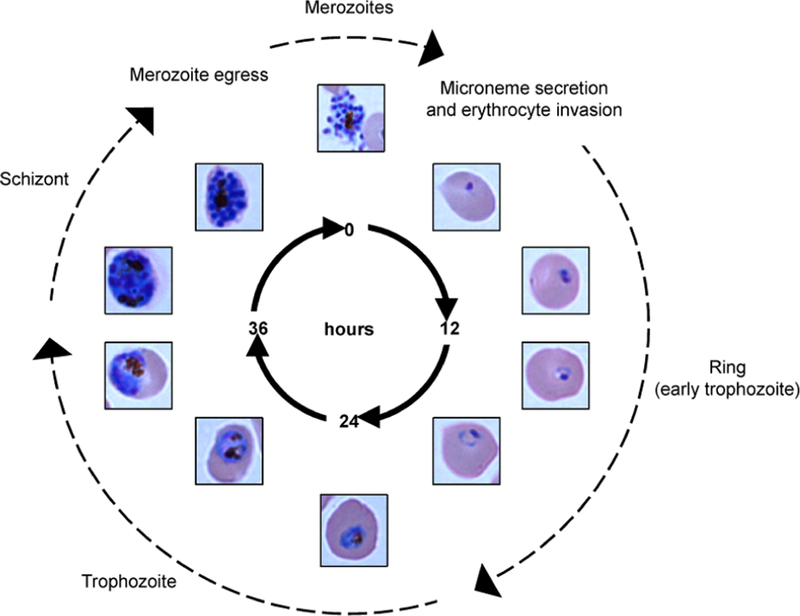

The blood-stage life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum lasts approximately 48 h and is characterized by progression from an intracellular ring-stage parasite through a highly metabolically active trophozoite and, finally, into a segmented schizont comprised of 16–24 merozoites (Figure 1). At the end of each life cycle, merozoites rupture the iRBC to invade healthy, neighboring erythrocytes. Pf CDPK1 localizes to the merozoite membrane throughout schizogony and merozoite egress and has been shown to play an essential role in merozoite invasion of host erythrocytes.9,10

Figure 1.

Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage life cycle. Merozoites invade and infect healthy red blood cells within the host bloodstream. Inside the red blood cell, the parasite develops from a young, ring-stage trophozoite into a mature, metabolically active trophozoite. The trophozoite undergoes multiple rounds of nuclear division, or schizogony, to produce a mature, segmented schizont composed of 16–24 merozoites. The schizont ruptures the red blood cell, releasing merozoites into the bloodstream to complete the cycle. Pf CDPK1 is expressed throughout the parasite life cycle and, especially, on the surface of merozoites where it plays an essential role in microneme secretion and erythrocyte invasion.

It was previously shown that peptides designed to mimic portions of the Pf CDPK1 J domain could successfully inhibit recombinant Pf CDPK1 (rCDPK1) as well as inhibit merozoite invasion.9 Similarly, after validating in vitro inhibition of rCDPK1 by both full-length and partial J domain, it was demonstrated that CDPK1-dependent parasite arrest occurred following transfection with a conditionally expressed J-GFP fusion protein.11 Although maximal recombinant kinase inhibition was attained with the full-length J domain sequence, both studies found that shorter C-terminal peptides demonstrated high binding affinity and significant inhibition of rCDPK1.

On the basis of these studies, we explored whether a chemically constrained peptide could be designed to mimic the autoinhibitory J domain of Pf CDPK1. We modeled our J domain disruptor (JDD) stapled peptide after the C-terminal portion of the Pf CDPK1 J domain. JDD was found to be selectively permeable to schizont-iRBC and displayed enhanced uptake by late-stage iRBC, consistent with previous studies with STAD-2.9,10 In addition, JDD was found to colocalize with merozoites within schizont-iRBC as demonstrated in previous studies showing Pf CDPK1 localization to the merozoite plasma membrane.10,11 In vitro studies with purified Pf CDPK1 showed that JDD inhibited the catalytic activity of recombinant enzyme. Further, JDD exhibited antiplasmodial activity by causing a defect in erythrocyte invasion that was consistent with previous studies showing blockage of invasion by J domain-associated peptides as well as the CDPK1 small molecule inhibitor, K252a.9,10 The work herein demonstrates that the stapled JDD peptide can inhibit Pf CDPK1 in iRBC and illustrates that chemically constrained peptides may serve as instrumental tools for exploring the function of malaria protein targets.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

JDD Design.

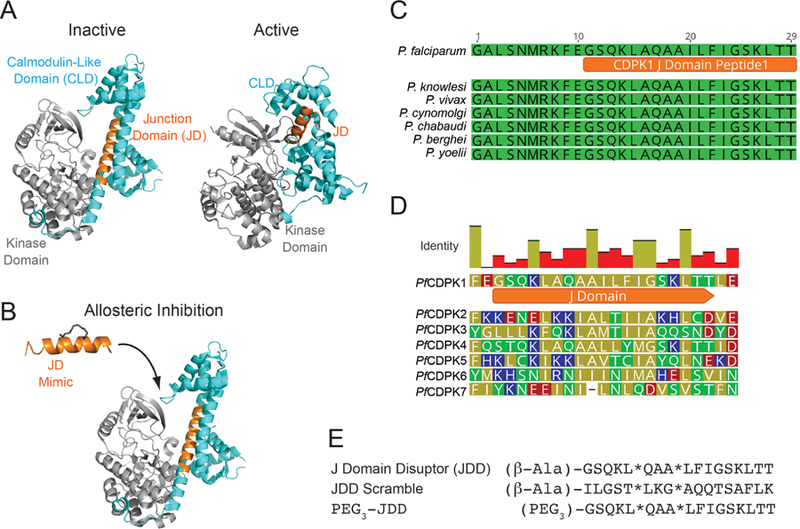

The CDPK family is structurally characterized by a S/T kinase domain linked to four EF-hand domains that function analogously to calmodulin.12 Between the catalytic and calmodulin-like domains (CLD) lies an autoinhibitory junction domain (J domain). At basal Ca2+ levels, the J domain is thought to serve as a pseudosubstrate, blocking the active site of the enzyme and inhibiting kinase activity (Figure 2a). Following a tightly regulated increase in intracellular Ca2+, binding of Ca2+ to the CLD triggers a conformational change characterized by increased intramolecular interactions between the CLD and the J domain and subsequent enzyme activation.13,14 As a strategy to inhibit Pf CDPK1 activity, we designed the inhibitory JDD peptide to mimic the J domain with the goal of allosterically sequestering Pf CDPK1 into an inactive conformer (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

JDD synthesis and function. (A) A model of Pf CDPK1 demonstrates binding of the autoinhibitory J domain between the calmodulin-like domain (CLD, blue) and the kinase domain of CDPK1 (gray) to allosterically regulate CDPK1 activity. Structures were rendered in Pymol using PDB files 3KU2 (inactive form, T. gondii) and 3Q5I (active form, P. bergheii). (B) JDD (orange) was designed to mimic the autoinhibitory J domain of native Pf CDPK1 and lock the enzyme into an inactive state. (C) Multiple sequence alignment of the J domain region from several Plasmodium species demonstrates high conservation of the J domain between species while (D) alignment of the J domain regions of all Pf CDPK proteins shows low conservation and, therefore, high specificity of JDD for Pf CDPK1. (E) The sequences of the J domain disruptor (JDD) peptide, PEG3-JDD, and JDD scramble are shown. Stars represent sequence positions of (S)-2-(4′-pentenyl)alanine.

Multiple sequence alignment of the J domain of CDPK1 from various Plasmodium species revealed the domain to be 100% identical between Plasmodium species (Figure 2c). Meanwhile, J domain alignments of all known Pf CDPK proteins showed low conservation at the amino acid level, suggesting that a JDD peptide may selectively inhibit Pf CDPK1 over the other Pf CDPK family members (Figure 2d). On the basis of these alignments, as well as previous studies demonstrating that the C-terminal region of the J domain most strongly binds and inhibits CDPK1,9,11 we designed a J domain peptide to mimic the C-terminal helical region of the Pf CDPK1 J domain. The α-helical peptide was chemically constrained through peptide “stapling” by incorporating non-natural olefinic amino acids into the expected solvent-exposed face of the peptide sequence followed by ring-closing metathesis (Figure 2e).

JDD Is Selectively Permeable to Schizont iRBC.

In order for JDD peptides to reach the Pf CDPK1 target, JDD must first gain access to the intracellular parasite. Peptide stapling was previously shown to have the potential to improve cell permeation in a variety of cells including RBCs.6,15–19 Although the full details of cell permeability in iRBC are not fully elucidated, most solutes are thought to be taken up via a Plasmodium Surface Anion Channel (PSAC) that is expressed by the parasite on the erythrocyte membrane during the latter stages of the blood-stage life cycle. This nonspecific channel provides the intracellular parasite with essential nutrients such as amino acids, sugars, anions, purines, and vitamins.20 Despite the broad spectrum of PSAC-permeable solutes, it appeared that channel permeability may be limited to low molecular weight molecules.21 Therefore, our initial studies sought to explore whether the ∼2 kDa JDD peptide could permeate iRBC.

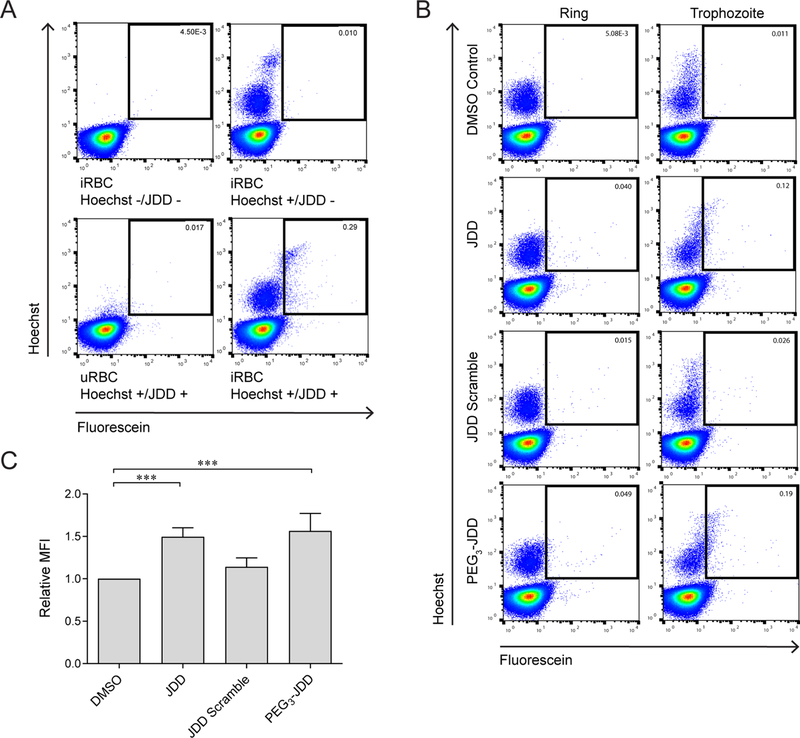

Permeation was first examined by incubating 1 μM fluorescein-conjugated JDD peptides with uninfected red blood cells (uRBC) and P. falciparum iRBC for 6 h under standard culture conditions. Following incubation, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Given that an increase in Hoechst signaling indicates higher quantities of DNA, cells demonstrating the highest levels of Hoechst staining represented those containing parasites that had undergone DNA replication or schizont-iRBC. On the other hand, cells with baseline Hoechst staining represented anucleate uRBC. JDD-treated cells contained a subpopulation of cells, schizont-iRBC, that were selectively permeant to the peptide as evidenced by high levels of Hoechst staining in the fluorescein-positive iRBC population (Figure 3a). Uninfected cells showed no enrichment of the fluorescein signal, indicating the peptide was only permeant to iRBC but not uRBC.

Figure 3.

JDD is selectively permeable to schizont-infected red blood cells. (A) iRBC were treated for 6 h with 1 μM fluorescein-conjugated JDD, stained with Hoechst 33342 DNA stain, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells that stained positive for both Hoechst and fluorescein are marked by boxes and indicate iRBC that took up fluorescein-conjugated peptides. JDD demonstrated selective permeability to schizont-iRBC, as evidenced by high Hoechst staining in the fluorescein-positive population. JDD uptake was negligible in early parasites and uRBC. (B) Treatment of synchronous ring-stage or late-stage (trophozoite) cultures with 1 μM fluorescein-conjugated JDD, JDD scramble, or PEG3-JDD demonstrated increased uptake of both JDD and PEG3-JDD by schizont-iRBC relative to ring-stage or early trophozoite iRBC. JDD scramble demonstrated negligible permeability regardless of parasite stage. (C) Median fluorescence intensity of late-stage, Hoechst-positive iRBC following treatment with JDD, JDD scramble, or PEG3-JDD showed no significant difference between JDD and PEG3-JDD uptake (***: p < 0.001; median fluorescence intensity relative to DMSO control, n = 4, mean ± S.E., one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

In order to further explore the parasite-stage specificity of JDD uptake, iRBC were synchronized using 5% d-sorbitol, and peptide permeation was measured in ring-versus late-stage iRBC. Consistent with the previous findings, late-stage iRBC demonstrated increased JDD uptake relative to ring and early trophozoite iRBC (Figure 3b). These data are also consistent with previous studies showing increased expression of Pf CDPK1 in late schizonts.9,10 As a control, ring- and late-stage iRBC were treated with scrambled JDD peptides possessing identical chemical composition to JDD but with a scrambled amino acid sequence. Interesting, the JDD scramble control, which contains identical chemical composition but an altered sequence, demonstrated negligible permeability to iRBC regardless of parasite stage demonstrating that permeation by JDD appears to be sequence-specific (Figure 3b).

Since JDD showed only moderate permeability in very late-stage iRBC, we explored whether addition of a short polyethylene glycol linker (PEG3), and its resultant increase in peptide solubility, would influence JDD permeability to iRBC. Analysis by flow cytometry demonstrated permeability patterns of PEG3-JDD to be largely comparable to those of the parent JDD peptide (Figure 3b). Quantification of the median fluorescein intensity of iRBC treated with JDD and PEG3-JDD demonstrated similar uptake of both peptide variants (Figure 3c, p < 0.001). Altogether, these results suggest that JDD uptake is highly stage-specific, allowing peptides to only permeate or be intracellularly retained at the late schizont stage, which also correlates with the stage when Pf CDPK1 is most highly expressed.9

JDD Is Not Hemolytic.

Since previous studies with the stapled peptide STAD-2 found that it demonstrated PKA-independent hemolytic activity in iRBC,6 we wondered if such lytic activity was specific to STAD-2 or was, rather, a byproduct of stapled peptide uptake. If the latter, such nonspecific lytic activity might hinder JDD from reaching its intended target in iRBC. Since JDD, like STAD-2, demonstrates selective permeability to iRBC, we sought to explore whether JDD peptides were capable of inducing iRBC lysis. To address this question, synchronous late-stage iRBC were serially diluted to yield samples of equal hematocrit that ranged from 0% to 8% parasitemia. Samples were treated with 1 μM JDD, JDD scramble, or DMSO control for 6 h, after which the extent of cell lysis was determined by measuring the absorbance of oxyhemoglobin in the sample medium at λ = 415 nm. Unlike STAD-2, absorbance values for JDD-treated iRBC were comparable to those of controls indicating that JDD does not induce iRBC hemolysis and should, therefore, be unrestricted in reaching its intracellular protein target (Figure S1).

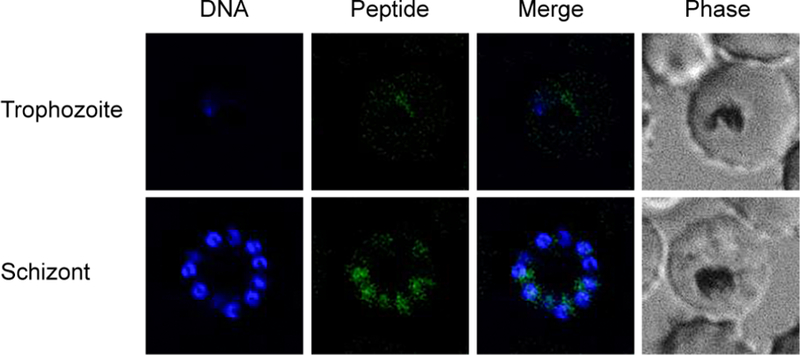

JDD Colocalizes with Merozoites in Segmented Schizonts.

To explore the localization of JDD in intracellular parasites, synchronous late-stage iRBC were treated with 1 μM fluorescein-conjugated JDD peptides for 6 h and subsequently Hoechst-stained. Live cells were then mounted on a coverslip and examined by fluorescence microscopy. While faint staining could be seen in trophozoite-iRBC, JDD fluorescence was most evident in late schizonts wherein JDD brightly colocalized with segmented merozoites (Figure 4). This pattern of colocalization is consistent with previous data showing that Pf CDPK1 localizes to the merozoite plasma membrane where it plays an important role in merozoite motility and microneme secretion.10

Figure 4.

JDD colocalizes with merozoites in late, segmented schizonts. Synchronous late-stage iRBC were treated with 1 μM fluorescein-conjugated JDD for 6 h, stained with Hoechst 33342, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. JDD demonstrated no colocalization with ring-stage parasites (data not shown), weak colocalization with more mature trophozoites, and strong colocalization with segmented schizonts. The pattern of fluorescein staining around nucleated daughter cells suggests JDD localization to the merozoites.

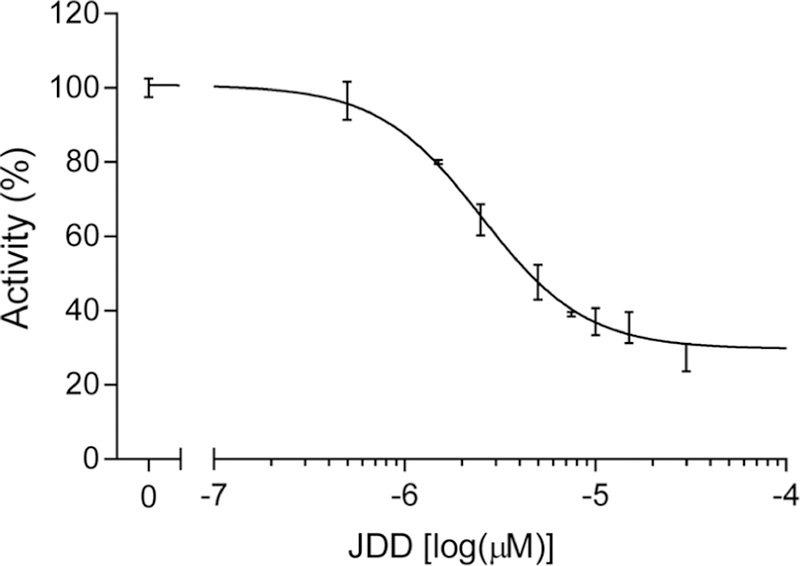

JDD Inhibits PfCDPK1 in Vitro.

Although JDD was designed to serve as an allosteric inhibitor of Pf CDPK1, it was not yet clear whether the peptide could indeed inhibit the enzyme. To address this, in vitro inhibition of rCDPK1 by JDD was assessed using a coupled enzymatic assay as previously described.22 In this assay, the conversion of NADH + H+ to NAD+ is coupled by a 1 to 1 stoichiometry to the phosphorylation of the synthetic protein kinase substrate, Syntide 2, by Pf CDPK1. Therefore, kinase activity is reflected by a reduction in absorbance at 340 nm. Changes in absorbance were monitored to assess kinase activity under various conditions. Kinase activity was assayed in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of JDD peptide (0 to 60 μM). The slope of absorption at 340 nm was measured to determine changes in kinase activity and plotted against the log concentration of JDD, yielding an IC50 of approximately 3.5 μM (Figure 5). This demonstrates that JDD can indeed allosterically inhibit Pf CDPK1.

Figure 5.

JDD inhibits rCDPK1 in vitro. Kinetic activity of purified, recombinant Pf CDPK1 (rCDPK1) was analyzed via an enzyme-coupled spectrophotometric assay. The reaction mixture was supplemented with 3 mM CaCl2, 200 μM Syntide II, and 80 nM rCDPK1 and assayed in the absence (100% of activity) or presence of increasing concentrations of JDD peptide (0 to 60 μM) for 60 s. Kinase activity was measured and plotted against the log concentration of JDD. An IC50 of 3.5 ± 1.2 μM was calculated (n = 4, sigmoidal dose response with variable slope).

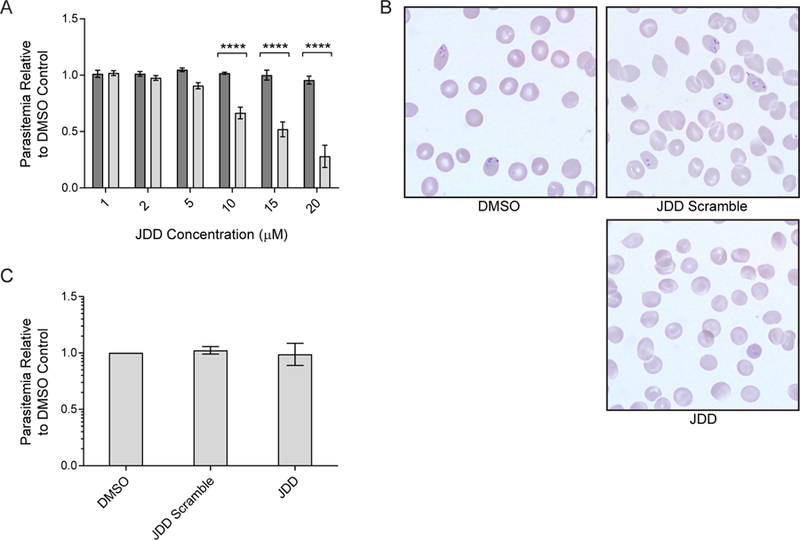

JDD Inhibits Merozoite Reinvasion.

Since in vitro analyses demonstrated JDD-mediated inhibition of Pf CDPK1 and since previous studies of J domain inhibitors found that binding of synthetic J domain constructs to Pf CDPK1 effectively arrested parasite development,9,11 we assessed whether treatment of late-stage iRBC with JDD stapled peptides would yield similar antiplasmodial activity. Late-stage iRBC were treated with 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, or 20 μM JDD or JDD scramble, and parasitemia was determined by flow cytometry at 24 h post-treatment. Although treatment with JDD scramble had no effect on parasite viability at any concentration tested, treatment with concentrations of ≥10 μM JDD yielded significant reductions in parasitemia by 24 h post-treatment (Figure 6a; ∼30% at 10 μM, ∼50% at 15 μM, and ∼70% at 20 μM; p < 0.0001). Analysis of Giemsa-stained blood smears showed a clear drop in the number of ring-stage iRBC following 20 μM JDD treatment, suggesting that JDD-treated parasites are defective in their ability to invade healthy erythrocytes (Figure 6b). Consistent with our findings of accumulation of the JDD stapled peptide only in late-stage parasites, no growth inhibition was observed when ring-stage parasites were exposed to 20 μM JDD (Figure 6c). Given the established role of Pf CDPK1 in merozoite invasion,9,10 these results suggest that JDD peptides effectively inhibit Pf CDPK1.

Figure 6.

JDD blocks merozoite reinvasion of erythrocytes. (A) Synchronous late-stage iRBC were treated with 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, or 20 μM JDD scramble (dark gray bars) or JDD (light gray bars), and parasitemia was determined by flow cytometry at 24 h post-treatment. Treatment with ≥10 μM JDD caused a significant drop in parasite viability (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, p < 0.0001, n = 3–8, mean ± S.E.). (B) Treatment of synchronous late-stage iRBC with 20 μM JDD blocked reinvasion of host erythrocytes by merozoites, as evidence by a lack of ring-stage iRBC 24 h post-treatment in JDD-treated cells. (C) Synchronous ring-stage iRBC treated with 20 μM JDD and analyzed by flow cytometry at 24 h post-treatment showed no change in viability of late-stage parasites.

Pf CDPK1 was first identified by Zhao et al. in 1993.23 Since then, numerous studies have examined the role of CDPK1 in Plasmodium parasites. Genetic disruption of this calcium-dependent kinase in blood-stage P. falciparum has been unsuccessful, suggesting that CDPK1 is essential to parasite asexual development.11,24 In addition, genetic knockdown of Plasmodium berghei CDPK1 showed the kinase to be indispensable during sexual development within the mosquito,25 indicating that CDPK1 may be essential throughout all stages of parasite development.

During the asexual life cycle, Pf CDPK1 has been shown to phosphorylate two key proteins: glideosome associated protein 45 (GAP45) and myosin A tail domain-interacting protein (MTIP).10,26 These proteins are members of the Plasmodium glideosome, an actin- and myosin-based motor complex that is anchored to the inner membrane complex (IMC) of the zoite pellicle and is essential for parasite gliding, invasion, and egress.27 Inhibition of Pf CDPK1 by small molecule inhibitors or peptides simulating regions of the J domain led to defects in microneme discharge and blockage in host cell invasion9,10 while inhibition with a full-length transgenic J domain arrested parasites in early schizogony.11

In this study, we show in vitro inhibition of Pf CDPK1 by the J domain disrupting stapled peptide JDD. Our results indicate that JDD effectively inhibits parasite growth via a CDPK1-mediated blockage in merozoite invasion. It should be noted that our experiments are fully consistent with the blockage of reinvasion previously reported by Bansal et al., who used a conventional peptide (P3) from the C-terminal region of the junction domain.9 In their work, treatment of merozoites with the peptide inhibited microneme discharge and, as we also observed, inhibited reinvasion of erythrocytes. However, we did not observe the arrest in parasite growth as reported by Azevedo et al. which was obtained using a conditionally expressed J-GFP fusion protein.11 In this work, early ring-stage parasites were exposed to the expressed J-GFP fusion protein, resulting in an arrest at early to mid-stage schizonts. This discrepancy is likely due to the stage-specific permeability of our JDD peptide, which shows little permeation into infected erythrocytes prior to schizogony. Our cell uptake data supports the notion that the JDD peptide is unable to reach the intracellular levels required for inhibition early enough in the parasite’s cell cycle to affect the arrest at the schizont stage.

It should also be noted that the concentration of JDD peptides necessary to achieve inhibition of reinvasion was significantly reduced in this study relative to previous studies, which required as high as 120 μM treatment with C-terminal partial peptides to achieve ∼42% inhibition of reinvasion.9 This enhanced efficacy is likely due to both the increased cellular permeation afforded by the hydrocarbon staple and the more specific binding interaction of the helical peptide relative to a disordered partial peptide. Furthermore, it is possible that Pf CDPK1-mediated inhibition of reinvasion could be achieved with incubation times shorter than 6 h, particularly for purified merozoites. Future studies will seek to further dissect this specific interaction and increase JDD efficacy in vitro by exploring inhibition using different regions derived from the J domain of Pf CDPK1. In addition, since the Plasmodium J domain is conserved between species, it will be interesting to explore the activity of JDD against P. berghei in vivo.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to utilize hydrocarbon stapled peptides in iRBC that are designed to specifically target proteins unique to P. falciparum. JDD peptides were designed to mimic the Pf CDPK1 autoinhibitory J domain and were selectively permeable to late, replicating schizonts. Analysis by fluorescence microscopy demonstrated JDD colocalization with merozoites in these late, dividing parasites. JDD inhibited recombinant enzyme activity in vitro and, at ≥10 μM concentration, significantly reduced parasite viability via blockage of erythrocyte invasion in vivo. Given CDPK1’s established role in microneme secretion, parasite motility, and host cell invasion, CDPK1 and its homologues are an attractive target. Our results demonstrate successful inhibition of Pf CDPK1 by JDD stapled peptides, provide support for the use of stapled peptides as potential antimalarial agents, and may assist toward validating CDPK proteins as a target for antimalarial drug development.

METHODS

Blood and Reagents.

Human O+ red blood cells were either purchased from Interstate Blood Bank, Inc. or donated by healthy volunteers. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Georgia (no. 2013102100); all donors signed consent forms. Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals and reagents for this study were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific.

Parasite Culture and Synchronization.

Plasmodium falciparum CS2 parasites were maintained in continuous culture according to routine methods. Parasites were cultured at 4% hematocrit in O+ red blood cells. Cultures were maintained in 25 or 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks at 37 °C under a gas mixture of 90% nitrogen/5% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide and in complete culture medium made up of RPMI containing 25 mM HEPES, 0.05 mg/mL hypoxanthine, 2.2 mg/mL NaHCO3 (J.T. Baker), 0.5% Albumax (Gibco), 2 g/L glucose, and 0.01 mg/mL gentamicin. Ring-stage cultures were treated routinely with 5% d-sorbitol to maintain cultures with synchronous parasite life cycles.

JDD Synthesis and Purification.

Peptides were synthesized on rink amide MBHA resin (Novabiochem) using standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase synthesis as previously described.19 JDD design was based off a multiple sequence alignment of the J domain regions from various species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, XP_001349680; P. vivax, XP_001612872; P. chabaudi chabaudi, XP_745235.1; P. knowlesi strain H, XP_002257860; P. cynomolgi, XP_004225327; P. berghei ANKA, XP_675880; P. yoelii, XP_727189). Alignments were conducted using the MUSCLE algorithm in Geneious software (version 10.2.3).28 Olefin metathesis was performed on solid support before the addition of the N-terminal PEG3 linker (ChemPep). Ring-closing metathesis was performed using Grubbs Catalyst, first generation (0.4 equiv in DCE; Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was performed twice for 1 h at room temperature. N-Terminal labeling was performed using 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (2 equiv; Acros) in DMF with HCTU (0.046 M) and DIEA (2% v/v) overnight at room temperature. After cleavage from resin, peptides were verified by ESI-MS and purified by HPLC. JDD peptide (FAM-βAla-GSQKL*QAA*LFIGSKLTT) expected mass: 2441.9, actual mass: 2441.0; JDD scramble (FAM-βAla-ILGST*LKG*AQQTSAFLK) expected mass: 2441. 9, actual mas s : 2 4 41.2; PEG 3 -JDD (FAM-PEG3-GSQKL*QAA*LFIGSKLTT) expected mass: 2560.0, actual mass: 2559.4. Stars represent incorporation of the non-natural olefinic amino acid (S)-N-Fmoc-2-(4′-pentenyl) alanine (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell Permeation by JDD.

Synchronous ring-stage or late-stage infected red blood cells (iRBC) and uninfected red blood cells (uRBC) were brought to 4% hematocrit in complete culture medium. Fluorescein-conjugated peptides were added to a final concentration of 1 μM, and cultures were incubated for 6 h at 37 °C under standard gas conditions. Following incubation, 25 μL of cell mixture was removed and stained with 100 μL of 2 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were subsequently washed once in 1 mL of 1× PBS, resuspended in 300 μL of 1× PBS, and analyzed for Hoechst and fluorescein staining on a Beckman Coulter CyAn flow cytometer. 500 000 events were collected at a rate of 15 000–20 000 events per second. Data was analyzed using FlowJo X single cell analysis software (FlowJo LLC).

Fluorescence Microscopy.

Late-stage iRBC were brought to 4% hematocrit in complete culture medium and transferred to a T25 tissue culture flask. Fluorescein-conjugated JDD was added to a final concentration of 1 μM after which the culture was incubated for 6 h at 37 °C under standard gas conditions. Following incubation, 50 μL of cell culture was removed and washed twice with 1 mL of 1× PBS. Cells were subsequently stained with 200 μL of 2 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 10 min at 37 °C. After staining, cells were washed twice with 1× PBS, deposited on a glass microscope slide, covered with a glass coverslip, and sealed. Live cells were immediately imaged with a DeltaVision II microscope system using an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope and a CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera. 0.2 μm z-stacks were acquired and deconvolved using SoftWorx 5.5 acquisition software (Applied Precision, Inc.).

Hemolysis Studies.

Synchronous late-stage iRBC were mixed with uRBC in order to achieve a series of samples with stepwise decreasing parasitemia. Samples were brought up to 4% hematocrit in complete culture medium containing 1 μM JDD, 1 μM JDD scramble, or 0.001% DMSO and transferred to a 48-well tissue culture plate in 200 μL aliquots in duplicate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C under standard gas conditions for 6 h. Following incubation, all samples were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 700 rcf for 5 min to pellet cells. 100 μL of supernatant was removed from each tube and transferred to a 96-well, flat-bottom tissue culture plate. Oxyhemoglobin absorbance was measured at 415 nm using a SpectraMax Plus microplate spectrophotometer with SoftMax Pro 5.4 software (Molecular Devices, LLC).

JDD IC50 Measurements.

IC50 values were determined in vitro by measuring kinase activity with varying concentrations of JDD. The kinase assay as described by Cook et al.22 determines the conversion of NADH + H+ to NAD+ as reflected by a reduction in absorbance at 340 nm. The reaction was performed in 100 mM MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)-propanesulfonic acid, pH 7.0) containing 1 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PEP (phosphoenol pyruvate), 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 200 mM NADH, 15 U/mL lactate dehydrogenase, and 8.4 U/mL pyruvate kinase. The assay by Cook et al.22 was modified with the addition of 3 mM CaCl2 to activate Pf CDPK1. Syntide II (PLARTLSVAGLPGKK, 200 μM) was used as a peptide substrate for Pf CPDK1. The reaction was started by adding 80 nM Pf CDPK1 to the reaction mix. After starting the kinase assay, the slope of absorption at 340 nm was measured for 60 s prior to adding JDD (ranging from 0 to 60 μM) to the reaction mixture and plotted against the log concentration of inhibitor. IC50 values were determined in duplicate from two independent measurements per protein preparation (two protein preparations were used for a total of n = 4). The IC50 values were determined using a sigmoidal dose response (variable slope) with the software Graph Pad Prism 6.

JDD Dose−Response in Late-Stage Parasites.

Synchronous late-stage iRBC at approximately 0.5% parasitemia were brought to 4% hematocrit in complete culture medium and transferred to a 24-well tissue culture plate in 1 mL aliquots. Plates containing uRBC or iRBC were supplemented with JDD or JDD scramble peptides to final concentrations of 1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 μM and subsequently incubated at 37 °C under standard gas conditions. Wells containing appropriate volumes of DMSO were also included as vehicle controls. At 24 h post-treatment, 25 μL was removed from each well and stained with 2 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for parasitemia analysis by flow cytometry. Giemsa-stained blood smears were also prepared at 24 h post-treatment to further assess parasite viability.

JDD Activity in Ring-Stage Parasites.

Synchronous ring-stage iRBC at 0.5% parasitemia were brought to 4% hematorcrit in complete culture medium and transferred to a 24-well tissue culture plate in 1 mL aliquots. Wells containing uRBC or iRBC were treated with 20 μM JDD, JDD scramble, or DMSO vehicle control for 24 h at 37 °C under standard gas conditions. At 24 h post-treatment, parasitemias were analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described.

Statistical Analyses.

Unless otherwise noted, all graphing and statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 7.02 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the National Institutes of Health (Grants 1K22A154600 and 1R03A188439 to E.J.K. and 2T32A1060546–06 to D.S.P.) for support of this work. In addition, F.W.H. would like to acknowledge Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant He1818/10) and the following grants from Kassel University: Future (PhosMOrg) and Graduate School “Clocks”.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Linear regression showing no significant difference in cell lysis between treatment conditions (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).WHO (2017) World Malaria Report 2017, WHO, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- (2).WHO (2015) World Malaria Report 2015, WHO, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mnzava AP, Knox TB, Temu EA, Trett A, Fornadel C, Hemingway J, and Renshaw M (2015) Implementation of the global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors: progress, challenges and the way forward. Malar. J 14, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Packard RM (2014) The origins of antimalarial-drug resistance. N. Engl. J. Med 371 (5), 397–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Petersen I, Eastman R, and Lanzer M (2011) Drug-resistant malaria: molecular mechanisms and implications for public health. FEBS Lett 585 (11), 1551–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Flaherty BR, Wang Y, Trope EC, Ho TG, Muralidharan V, Kennedy EJ, and Peterson DS (2015) The Stapled AKAP Disruptor Peptide STAD-2 Displays Antimalarial Activity through a PKA-Independent Mechanism. PLoS One 10 (5), No. e0129239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lucet IS, Tobin A, Drewry D, Wilks AF, and Doerig C (2012) Plasmodium kinases as targets for new-generation antimalarials. Future Med. Chem 4 (18), 2295–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Doerig C (2004) Protein kinases as targets for anti-parasitic chemotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 1697, 155–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bansal A, Singh S, More KR, Hans D, Nangalia K, Yogavel M, Sharma A, and Chitnis CE (2013) Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 (PfCDPK1) and its role in microneme secretion during erythrocyte invasion. J. Biol. Chem 288 (3), 1590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Green JL, Rees-Channer RR, Howell SA, Martin SR, Knuepfer E, Taylor HM, Grainger M, and Holder AA (2008) The motor complex of Plasmodium falciparum: phosphorylation by a calcium-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem 283 (45), 30980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Azevedo MF, Sanders PR, Krejany E, Nie CQ, Fu P, Bach LA, Wunderlich G, Crabb BS, and Gilson PR (2013) Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum CDPK1 by conditional expression of its J-domain demonstrates a key role in schizont development. Biochem. J 452 (3), 433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Harmon AC, Gribskov M, and Harper JF (2000) CDPKs - a kinase for every Ca2+ signal? Trends Plant Sci 5 (4), 154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nagamune K, and Sibley LD (2006) Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of calcium ATPases and calcium-regulated proteins in the apicomplexa. Mol. Biol. Evol 23 (8), 1613–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Harper JF, and Harmon A (2005) Plants, symbiosis and parasites: a calcium signalling connection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 6 (7), 555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang Y, Ho TG, Bertinetti D, Neddermann M, Franz E, Mo GC, Schendowich LP, Sukhu A, Spelts RC, Zhang J, Herberg FW, and Kennedy EJ (2014) Isoform-selective disruption of AKAP-localized PKA using hydrocarbon stapled peptides. ACS Chem. Biol 9 (3), 635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang Y, Ho TG, Franz E, Hermann JS, Smith FD, Hehnly H, Esseltine JL, Hanold LE, Murph MM, Bertinetti D, Scott JD, Herberg FW, and Kennedy EJ (2015) PKA-type I selective constrained peptide disruptors of AKAP complexes. ACS Chem. Biol 10 (6), 1502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kennedy EJ, and Scott JD (2015) Selective disruption of the AKAP signaling complexes. Methods Mol. Biol 1294, 137–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chu Q, Moellering RE, Hilinski GJ, Kim Y-W, Grossmann TN, Yeh JTH, and Verdine GL (2015) Towards understanding cell penetration by stapled peptides. MedChemComm 6 (1), 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fulton MD, Hanold LE, Ruan Z, Patel S, Beedle AM, Kannan N, and Kennedy EJ (2018) Conformationally constrained peptides target the allosteric kinase dimer interface and inhibit EGFR activation. Bioorg. Med. Chem 26 (6), 1167–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lisk G, and Desai SA (2005) The plasmodial surface anion channel is functionally conserved in divergent malaria parasites. Eukaryotic Cell 4 (12), 2153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Desai SA (2014) Why do malaria parasites increase host erythrocyte permeability? Trends Parasitol 30 (3), 151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Cook PF, Neville ME Jr., Vrana KE, Hartl FT, and Roskoski R Jr. (1982) Adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate dependent protein kinase: kinetic mechanism for the bovine skeletal muscle catalytic subunit. Biochemistry 21 (23), 5794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhao Y, Kappes B, and Franklin RM (1993) Gene structure and expression of an unusual protein kinase from Plasmodium falciparum homologous at its carboxyl terminus with the EF hand calcium-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem 268 (6), 4347–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kato N, Sakata T, Breton G, Le Roch KG, Nagle A, Andersen C, Bursulaya B, Henson K, Johnson J, Kumar KA, Marr F, Mason D, McNamara C, Plouffe D, Ramachandran V, Spooner M, Tuntland T, Zhou Y, Peters EC, Chatterjee A, Schultz PG, Ward GE, Gray N, Harper J, and Winzeler EA (2008) Gene expression signatures and small-molecule compounds link a protein kinase to Plasmodium falciparum motility. Nat. Chem. Biol 4 (6), 347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sebastian S, Brochet M, Collins MO, Schwach F, Jones ML, Goulding D, Rayner JC, Choudhary JS, and Billker O (2012) A Plasmodium calcium-dependent protein kinase controls zygote development and transmission by translationally activating repressed mRNAs. Cell Host Microbe 12 (1), 9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Thomas DC, Ahmed A, Gilberger TW, and Sharma P (2012) Regulation of Plasmodium falciparum glideosome associated protein 45 (PfGAP45) phosphorylation. PLoS One 7 (4), No. e35855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Frenal K, Polonais V, Marq JB, Stratmann R, Limenitakis J, and Soldati-Favre D (2010) Functional dissection of the apicomplexan glideosome molecular architecture. Cell Host Microbe 8 (4), 343–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, and Drummond A (2012) Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28 (12), 1647–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.