Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Staging preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD) by the expected years to symptom onset (EYO) in autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) through biomarker correlations is important.

METHODS:

We estimated the correlation matrix between EYO/cognition and imaging/CSF biomarkers, and searched for the EYO cutoff where a change in the correlations occurred before and after the cutoff among the asymptomatic mutation carriers of ADAD. We then estimated the longitudinal rate of change for biomarkers/cognition within each preclinical stage defined by the EYO.

RESULTS:

Based on the change in the correlations, the preclinical ADAD was divided by EYOs −7 and −13 years. Mutation carriers demonstrated a temporal ordering of biomarker/cognition changes across the three preclinical stages.

CONCLUSIONS:

Duration of each preclinical stage can be estimated in ADAD, facilitating better planning of prevention trials with the EYO cutoffs under the recently released FDA guidance. The generalization of these results to sporadic AD warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease, Biomarkers, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network, Preclinical Alzheimer Disease

1. Background

It is critical for prevention clinical trials of Alzheimer disease (AD) to determine the biological disease stages in the preclinical phase before symptoms are manifest but, yet also when the underlying disease pathology is present [1, 2]. Several methods have been proposed to stage preclinical AD using well-established biomarkers, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analytes, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) based regional brain volumes and cortical thickness, and molecular imaging of cerebral fibrillar amyloid with positron emission tomography (PET) using the [11C] benzothiazole tracer, Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB-PET), as well as metabolic imaging with [F-18] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) markers [2–4]. These methods typically employed the cutoff concept to dichotomize each biomarker as normal or abnormal and then use the combinations of these biomarkers to describe the disease stages [2–4]. Although these methods are intuitive and easy to use, they are entirely based on various modalities of biomarkers, and hence fail to provide the critical insight regarding how far each stage is from the expected symptom onset and how long each stage lasts until transitioning to the next, more severe stage. Importantly, these methods dichotomized each biomarker independently, ignoring the well-established correlations between biomarkers and clinical/cognitive outcomes [5]. To overcome these drawbacks, we focus on the preclinical phase of mutation carriers (MCs) with a known causative mutation of AD in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), or presenilin 2 (PSEN2) genes whose age of symptom onset can be estimated with relatively high accuracy [1, 6]. We conceptualize that the temporal cascade of preclinical biomarker changes [1–3] implies a potentially dynamic correlational structure between AD biomarkers and the expected years to symptom onset (EYO, see details in the Methods section) as well as cognition, depending on the specific stages of preclinical autosomal dominant AD (ADAD). Specifically, during an early preclinical stage, many biomarkers do not show meaningful biological changes, their variations may be considered as random, implying limited or less biologically meaningful correlations with the EYO/cognition. On the other hand, during a later preclinical stage, more biomarkers become active, which may lead to enriched correlations between biomarkers and the EYO/cognition. Based on this conceptualization, we stage the preclinical ADAD by correlating a set of AD biomarkers (CSF Aβ42, CSF total tau, MRI hippocampal volume and precuneus thickness, PET PiB cortical standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), and FDG PET cortical SUVR) directly with the EYO and cognition, and searching for the EYO cutoffs where a change in the correlations occurs before and after the cutoffs among the asymptomatic MCs of ADAD. These EYO cutoffs then naturally divide the entire EYO into different stages, and facilitate an estimation of the duration for each preclinical stage and hence better planning of prevention trials with the EYO cutoffs under the recently released FDA guidance. Finally, we validate these preclinical stages by estimating longitudinal rates of change for biomarkers/cognition within each EYO stage, and comparing them with estimates from the non-carriers (NCs) of mutations.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) is a longitudinal, international, observational study launched in 2008 to establish a registry of individuals from families with a known causative mutation of AD in the APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes. Biomarkers of multiple modalities were used in the DIAN to assess the preclinical progression of ADAD [1, 7]. This analysis included all asymptomatic DIAN participants (as of June 30, 2015), as defined by a baseline Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0 [1, 8]. Participants from families that carry the APP E693G (Dutch) mutation were excluded because of previous evidence of little neuritic plaque and neurofibrillary tangle pathology [9].

2.2. Expected Years to Symptom Onset (EYO)

The estimated age of symptom onset and the calculation of EYO for MCs of ADAD have been described in previous studies [1, 6, 7, 10]. Briefly, a meta-analysis was performed on the age of onset using individual-level data from 387 ADAD pedigrees with 3275 individuals which were compiled from 137 peer-reviewed publications, the DIAN database, and 2 large kindreds of Colombian (PSEN1 E280A) and Volga German (PSEN2 N141I) ancestry [6]. The number of individuals for each mutation ranged from 2 to 58. The meta-analysis reported summary statistics on age at symptom onset for 174 ADAD mutations, and found relatively high accuracy in predicting individual age of symptom onset by parental age of onset and/or mean age of onset from each mutation. Based on the meta-analysis, the EYO in DIAN was calculated as the difference between the age of the MCs and the mean mutation age of onset [1, 7, 10] (if not available, parental age of onset used). For example, if the estimated age of onset for a MC is 50 y, and this individual’s age is 40 y, then the EYO for the MC is −10 y. More details about the age of onset were given in Ryman et al [6]. This definition of EYO has been validated in multiple previous publications [1, 7, 10].

2.3. Clinical and Cognitive Assessments

The DIAN cognitive battery included 22 tests, described in detail in our previous publication [11]. Global cognition was assessed with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [12]. Measures of episodic memory included the immediate and delayed recall on the DIAN Word List Test [11], the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory immediate and delayed recall scores, and recognition of novel, intact, and mixed pairs from the Pair Binding test [13]. Semantic memory was assessed with category fluency for animals and vegetables [14], the Boston Naming test [15], and the Semantic Categorization task [11, 16]. Processing speed tests included the Trail Making Test Parts A & B [17] and the Digit Symbol Substitution test from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised [18]. Attention and working memory were assessed with the WAIS-R Digit Span forwards and backwards [18], and the Computation Span and Reading Span tests [11]. Visuospatial abilities were assessed with the Paper Folding Test [19] and the Spatial Relations test [19]. Cognitive control was assessed with the Consonant-Vowel Odd-Even Switching task [11, 20, 21] and the Simon Task [22]. A cognitive composite was computed using the 22 tests by averaging (hence equal weights) the z-scores using the mean (SD) at baseline from the raw scores of all tests.

2.4. Brain Imaging

2.4.1. MRI

As previously described, 3 Tesla volumetric T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were acquired and processed through FreeSurfer version 5.3 (Martinos Center, Boston, MA) [7, 23]. The T1-weighted images were used for measurements of hippocampal volumes adjusted for total intracranial volumes and for obtaining regional estimates of MRI precuneus thickness [7].

2.4.2. PET

T1-weighted images as described in 2.4.1 were used to obtain regional estimates of positron emission tomography (PET) data [7]. PiB-PET imaging data were acquired between 40 to 70 minutes after approximately 15 mCi injection of [C11] Pittsburgh compound B (PiB). Starting 30 minutes after a bolus injection of approximately 5 mCi of FDG and lasting 30 minutes, metabolic imaging with [F-18] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) was performed with a 3D dynamic acquisition [7]. A neocortical SUVR was used to determine levels of global fibrillar Aβ deposition and FDG metabolism, using cerebellar grey matter as the reference region and applying partial volume correction using a regional point spread function as previously described.

2.5. CSF Collection and Analyses

CSF was obtained by lumbar puncture in the morning following an overnight fast as previously described [24]. Samples were aliquoted and immediately placed on dry ice prior to storing at −80°C. Aβ42, total tau, and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (ptau) were measured by immunoassay (INNO-BIA AlzBio3; Fujirebio [formerly Innogenetics], Gent, Belgium). In order to limit methodological variability, a single immunoassay lot number was used, and longitudinal samples from a given individual were run on the same assay plate. Quality control (QC) criteria included a coefficient of variation (CV) of ≤25% for each sample run in duplicate (with a typical CV of less than 10%), kit controls within the range provided by the manufacturer, and consistency of two pooled QC CSF samples included on every plate.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics were described for MCs and NCs using mean (SD) or frequency (%), and tested using two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

2.6.1. Staging Preclinical ADAD

This cross sectional analysis was conducted on all asymptomatic MCs in the DIAN whose data were available on all modalities. Only baseline data were included in this analysis. We focused on the set of most important clinical/cognitive outcomes in the DIAN study: the EYO and the cognitive composite of the 22 tests, and the set of established AD biomarkers: CSF Aβ42 and total tau (ptau is highly correlated with total tau, hence not included in the list, but in the sensitivity analysis), PiB PET cortical SUVR, MRI precuneus thickness and total hippocampal volume, and PET FDG cortical SUVR. These same biomarkers have also been used in many classification schemes [2–4]. The conceptualization of differential correlation matrices between the set of biomarkers and the set of clinical/cognitive outcomes across different preclinical stages mandates a statistical test to compare the correlation matrix among asymptomatic MCs before and after each EYO cutoff. The null hypothesis is that all 12 component correlations in the matrix are the same before and after each EYO cutoff.

Using each integer EYO (denoted as EYOc) from −22 to −3 as a cutoff, we divided the entire cohort of asymptomatic MCs into two sub-cohorts, each with an adequate sample size (at least 20, see supplemental Table 1): MCs with EYO≤ EYOc, and those with EYO > EYOc. For each sub-cohort, a 2 by 6 correlation matrix was estimated using the set of clinical outcomes and the set of biomarkers. Each matrix was then transformed using the Fisher’s z-transformation component-wise [25]. The maximum of the absolute values on the differences of the transformed correlations between two sub-cohorts across 12 components was used as the test statistic, which, after normalization, can be approximated by a standard normal distribution [25]. Let Z be the standardized test statistic. The type I error was controlled through Sidak-Bonferroni correction to maintain an overall level of 0.05 where the critical point was chosen to satisfy 1 − (1 − (P(Z < −zcritical point) +P(Z > zcritical point)))12 = 0.05 [26]. The first EYO cutoff to divide preclinical phase of ADAD was chosen as the EYOc that maximized the test statistics Zs across all choices of EYO cutoffs, and rejected the null hypothesis (of two equal correlation matrices) at a significance level of 5%. After the first EYO cutoff was chosen to divide preclinical phase into two sub-stages, we applied the same procedure again to further divide each into two finer stages if the statistical test rejected the corresponding null hypothesis. We stopped the procedure when further division of EYO resulted in no statistically significant tests. Bootstrapping method was used to estimate the standard error (SE) of the EYO cutoffs. The same method was also applied to all NCs.

2.6.2. Longitudinal Change at Each Preclinical Stage

We next estimated and compared the longitudinal rate of change (per year) between MCs and NCs on the biomarkers and cognition to validate the preclinical stages as defined by the cross sectional analysis in 2.6.1., using general linear mixed effects models(LMEs, [27]). The fixed effects were: mutation status (MC vs. NC), time, preclinical stages as estimated above, and all the two-way and there-way interactions between them. The model also included a random effect to account for the family clusters, and random intercept and slope for each individual to account for the correlation across times within individuals. The longitudinal rate of change was estimated for biomarkers and the cognition composite that combined four tests with most longitudinal data in the DIAN: delayed recall of the DIAN word list learning test and delayed paragraph recall from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory test, complex attention and processing speed (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Digit Symbol Substitution Test), and MMSE [10, 28].

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Two hundred individuals were cognitively normal at baseline and had assessments on all the outcomes (cognition, CSF, MRI, amyloid PET, and FDG PET). MCs (N=116) and NCs (N=84) were not significantly different in the presence of an APOE ε4 allele, age, sex, MRI Precuneus Thickness, MRI Hippocampus Volume, and FDG Cortical SUVR, but were different in CSF biomarkers and in PiB cortical SUVR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (N=200)

| Variable Mean (SD) | aMC (n=116) | Non-MC (n=84) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean | 34.4 (8.6) | 34.9 (8.2) | 0.69 |

| Female, n (%) | 64 (55.2) | 46 (54.8) | 0.95 |

| APOE ε4+, n (%) | 33 (28.7) | 22 (26.2) | 0.72 |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | 379.0 (175.3) | 440.6 (146.6) | 0.01 |

| CSF Total Tau, pg/mL | 81.8 (44.7) | 53.9 (22.7) | <0.0001 |

| CSF Ptau, pg/mL | 47.9 (27.3) | 29.0 (9.4) | <0.0001 |

| PIB Cortical SUVR | 1.57 (0.69) | 1.03 (0.06) | <0.0001 |

| MRI Precuneus Thickness | 4.73 (0.26) | 4.78 (0.24) | 0.16 |

| MRI Hippocampus Volume | 8898.6 (976.1) | 8946.9 (758.9) | 0.069 |

| FDG Cortical SUVR | 1.71 (0.13) | 1.71 (0.14) | 0.89 |

| PSEN1, n (%) | 84 (72.4) | 55 (65.5) | 0.43 |

| PSEN2, n (%) | 14 (12.1) | 10 (11.9) | |

| APP, n (%) | 18 (15.5) | 19 (22.6) |

aMC: asymptomatic mutation carriers, Non-MC: mutation non-carriers

3.2. Preclinical Stages

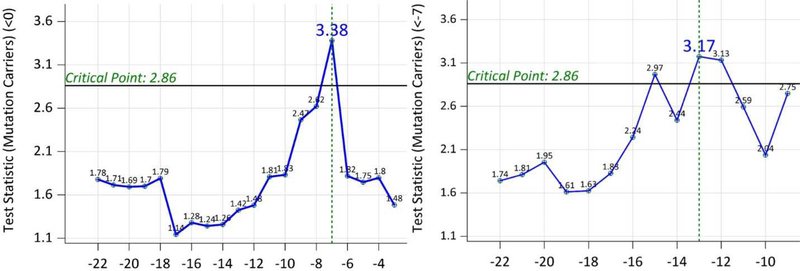

The test statistics using baseline data from 116 MCs indicated a significant difference on the correlation matrix of clinical/cognitive outcomes and biomarkers at EYOc = −7 years (SE=5.9 years, Figure 1). This test statistic at EYO=−7 years was achieved by the correlation (r) between PiB SUVR and EYO (r=0.389 before EYO −7 years, r=−0.362 after EYO −7 years. Further tests using all MCs with EYO ≤ −7 indicated another significant difference on the correlation matrix at EYOc = −13 years(SE=3.7 years, Figure 1). This maximum test statistic at EYO −13 years came from the correlation between FDG PET and the cognition (r=0.316 before EYO −13, r=−0.426 after EYO −13 years). Therefore, the entire preclinical phase can be divided into 3 sub-stages by the EYO: (−35, −13], (−13, −7], and (−7, 0). Figure 2 showed the scatter plots of individual biomarkers and cognition over the EYO with LOESS curves for MCs [29]. When CSF ptau instead of CSF total tau was used, the same 3 stages were obtained.

Figure 1:

Left Panel—Test statistics from the testing of the equality of the correlation matrices using all the data (EYO −7 was selected) of mutation carriers; Right Panel—Test statistics from the testing of the equality of the correlation matrices using mutation carriers with baseline EYO ≤−7 (EYO −13 was selected). The critical point for determining significance was adjusted to control Type I error.

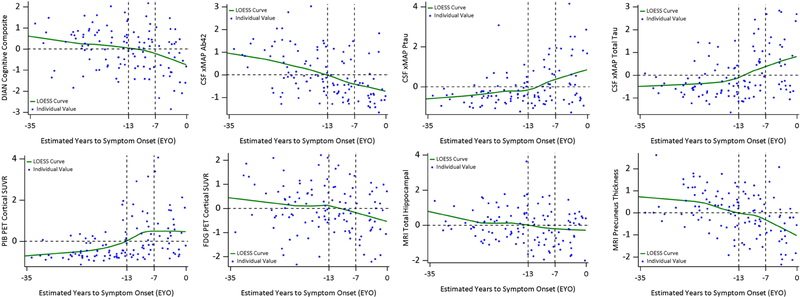

Figure 2:

Individual values and LOESS curves over EYO for mutation carriers. All outcomes were standardized for ease of comparison using the mean (SD) of the whole cohort and to avoid unblinding mutation status. EYO −13 and −7 separated the preclinical phase into three stages. The y-axis reference line 0 represented the group mean. PiB PET exhibited a clear plateau around EYO −7 years and FDG PET started a decline around EYO −13 years. All the outcomes crossed the horizontal line of 0 (the mean of the entire cohort after normalization) at the transitioning EYO stage (−13, −7].

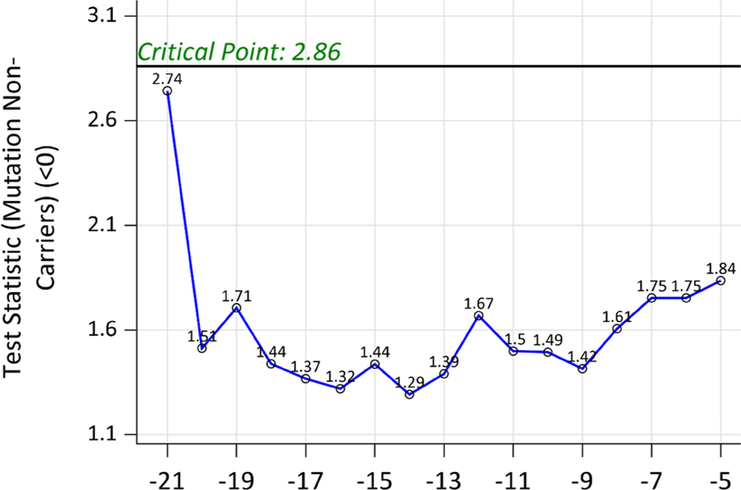

When the same method was applied to all NCs, no test statistic was significant (Figure 3), indicating no differential correlation matrix of clinical/cognitive outcomes and biomarkers across entire span of EYO. Figure 4 showed the scatter plots of individual biomarkers and cognition over the EYO with LOESS curves for NCs.

Figure 3:

Test statistics from the testing of the equality of the correlation matrices using all the data for mutation non-carriers. No test statistic was significant during the entire span of EYO

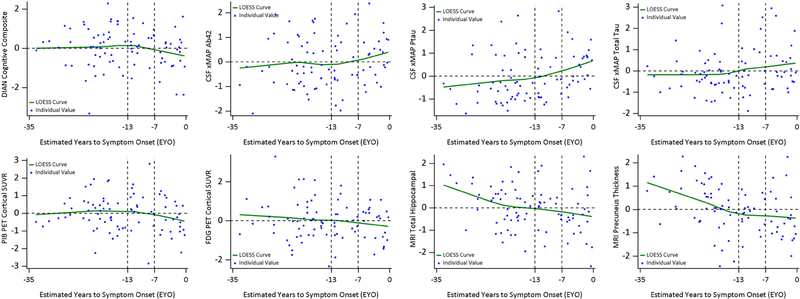

Figure 4:

Individual values and LOESS curves over EYO for mutation non-carriers (NCs). All outcomes were standardized for ease of comparison using the mean (SD) of the whole cohort and to avoid unblinding mutation status. EYO −13 and −7 did not separate the preclinical phase into three stages based on NCs. The y-axis reference line 0 represented the group mean. NCs did not show a consistent transitioning pattern across the entire EYO, particularly for PiB PET and FDG PET

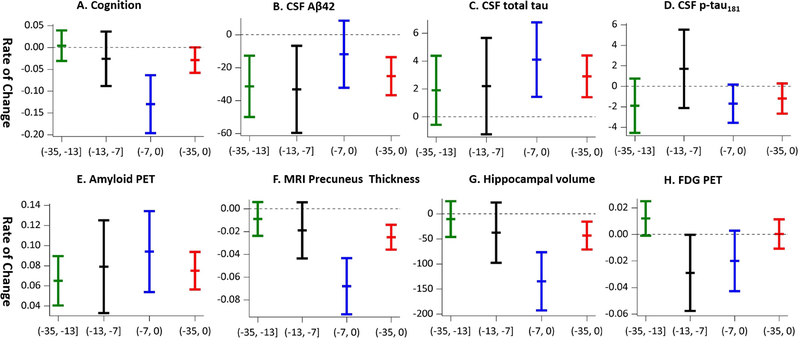

3.3. Longitudinal Rates of Change for Biomarkers and Cognition

Eighty one MCs and 61 NCs had longitudinal data on biomarkers or cognition in the DIAN, and participated in the longitudinal analyses. The mean (SD) of longitudinal follow-ups is 3.0 (1.2) years. As expected, the longitudinal change was not significant for NCs at any of the three preclinical stages by EYO cut points −7 years and −13 years (Table 2). In contrast, MCs demonstrated longitudinal increase or decrease in almost all biomarkers (Table 2, Figure 5). In fact, the longitudinal rate of change (in absolute value) increased as the preclinical stages became closer to the symptom onset for cognition, CSF total tau, PiB PET cortical SUVR, MRI precuneus thickness, and MRI total hippocampal volume, with the exception of CSF Aβ42 (Table 2, Figure 5) where the most dramatic changes occurred at the earlier preclinical stages. The longitudinal change on FDG PET also approached statistical significance at the EYO stage (−13, −7] (Table 2, Figure 5). For comparison, the rate of change for the entire cohort of asymptomatic MCs was also reported in Table 2.

Table 2:

The rate of change for each outcome by preclinical stages and by mutation status (N=142)*

| Markers | Asymptomatic Mutation carriers (N=81)~ | Mutation non-carriers (N=61)~ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EYO stage (−35, −13], Slope (SE), N=43 | EYO stage (−13, −7], Slope (SE), N=16 | EYO stage (−7, 0), Slope (SE), N=22 | Overall Preclinical Stage (−35, 0) | EYO stage (−35, −13], Slope (SE), N=32 | EYO stage (−13, −7], Slope (SE), N=12 | EYO stage (−7, 0), Slope (SE), N=17 | Overall Preclinical Stage (−35, 0) | |

| DIAN Cognitive Composite | 0.004(0.019) | −0.026 (0.033) | −0.13 (0.035) | −0.029 (0.016) | −0.01 (0.019) | −0.01 (0.035) | −0.02 (0.032) | −0.01 (0.02) |

| CSF Aβ42, pg/mL | −31.4 (9.8) | −33.2 (13.8) | −11.9 (10.7) | −25.2 (6.2) | −0.8 (10.7) | −9.4 (13.5) | −4.1 (15.0) | −4.4 (7.0) |

| CSF Total Tau, pg/mL | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.4) | 2.9 (0.8) | −0.1 (1.5) | 0.4 (1.8) | −0.8 (1.9) | −0.10 (0.98) |

| CSF Ptau, pg/mL | −1.9 (1.4) | 1.7 (2.0) | −1.7 (1.0) | −1.2 (0.8) | −0.5 (1.5) | −1.0 (1.9) | −3.0 (1.7) | −1.5 (1.1) |

| PIB PET Cortical SUVR | 0.065 (0.013) | 0.079 (0.024) | 0.094 (0.021) | 0.075 (0.010) | 0.001 (0.014) | −0.018 (0.028) | 0.016 (0.020) | 0.002 (0.01) |

| MRI Precuneus Thickness | −0.009 (0.008) | −0.019 (0.013) | −0.068 (0.013) | −0.025 (0.006) | −0.014 (0.008) | −0.014 (0.016) | 0.005 (0.013) | −0.010 (0.007) |

| MRI Total Hippocampal | −10.5 (19.2) | −37.6 (31.7) | −134.7 (30.6) | −43.4 (15.2) | −11.9 (20.6) | −0.18 (38.1) | −39.5 (32.2) | −16.4 (16.7) |

| FDG PET Cortical SUVR | 0.012 (0.007) | −0.029 (0.015) | −0.020 (0.012) | 0.0003 (0.006) | 0.013 (0.008) | 0.006 (0.014) | 0.008 (0.012) | 0.011 (0.006) |

Significant rates of change are in bold.

N varied slightly from marker to marker due to unbalanced missing data.

Figure 5:

The rate of change for each outcome for mutation carriers by disease stages and for the overall preclinical stage. Each vertical line includes three tickers for the mean and 95% confidence interval. If the vertical line covers the 0 on the y-axis, the rate of change is not significant. Only amyloid PET has significant rate of change over all three stages (thus the reference line is not shown).

4. Discussion

Taking advantage of the availability of relatively accurate estimates of the age at symptom onset from asymptomatic MCs of ADAD and the rich clinical/cognitive and biomarkers databases in the DIAN, we found that preclinical ADAD can be staged into 3 distinctive stages by EYO: at least 13 years prior to symptom onset, between 13 years and 7 years prior to symptom onset, and within 7 years of symptom onset. To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the very first that attempted to directly stage preclinical AD by how far the asymptomatic individuals were from their symptom onset. Our classification methodology is novel, compared with the existing methods [2–4]. In fact, all existing methods staged preclinical AD almost exclusively by biomarkers, using various cutoffs to define biomarker positivity and negativity. These methods failed to provide the critical insight regarding how far each stage is from the symptom onset and how long each stage lasts until transitioning to the next, more severe stage, and completely ignored the dynamic correlations between many of the biomarkers and clinical/cognitive outcomes which may depend on the specific stages. Further, the operationalization of these methods was often inconsistent across studies with variable cutoffs, even for the same biomarkers from the same labs, resulting in non-reproducible findings. In contrast, our method did not dichotomize biomarkers, and was data-driven by the pattern of correlations between biomarkers and the EYO/cognition. Importantly, the three preclinical stages we found are consistent with the NIA-AA criteria and A/T/N classification [2, 3].

The three preclinical stages was further validated by our longitudinal analyses, which showed that only CSF Aβ42 and PiB PET had significant longitudinal changes in MCs who were in the earliest preclinical EYO stage (−35, −13], supporting the hypothesized temporal orderings of biomarker changes and the use of amyloidosis pathology as the main staging biomarker in this stage [2–4]. Significant longitudinal changes were observed in MRI total hippocampal volumes, MRI precuneus thickness, CSF total tau, and the cognitive composite for MCs who were in the closest preclinical stage to symptom onset, EYO in (−7, 0), again, supporting the hypothesized temporal orderings of biomarker changes and demonstrating the appropriateness of using these markers to track the disease progression in the latest preclinical stage [2–4]. However, in the transitioning stage, EYO in (−13, −7], no other biomarkers demonstrated significant changes except for the amyloid biomarkers and perhaps the FDG PET SUVR. The rate of longitudinal change in CSF total tau at this stage was not significant (2.2 pg/mL/year, SE=1.8), likely due to a lack of statistical power with a limited sample size. The test statistics for EYOs −12, −13, and −15 were close, suggesting the estimated EYO cutoff of −13 year may be subject to variation from −15 to −12 years. Importantly, no significant longitudinal changes were observed for NCs.

Knowing approximately the duration of each preclinical stage and how far each is from symptom onset has important practical implications on designing prevention AD trials. Our results suggest the EYO stage (−13, −7] can last for 6 years and the EYO stage (−7, 0) about 7 years. Unless a more sensitive cognitive outcome can be identified, a secondary prevention trial enrolling participants at the EYO (−13, −7] stage with a longitudinal follow-up of 2 to 4 years may miss sufficient cognitive decline in the placebo group to detect the treatment effect. To guarantee the desired decline in the placebo group, a secondary prevention trial may need to plan a longer follow-up so that a significant portion of the participants will enter the EYO (−7, 0) stage during the follow-up, and/or enroll enough participants in the later part of the EYO stage (−13, −7] (i.e., closer to −7) so that they will cross to the EYO stage (−7, 0) where cognitive decline accelerates. For prevention trials on sporadic AD, however, EYO is not readily available. The correlations between the EYO/cognition and the set of all major biomarkers may be extrapolated into the preclinical stages of sporadic AD, which then might allow a prediction of the EYO for asymptomatic individuals of sporadic AD by the set of major biomarkers. For a primary prevention trial of ADAD enrolling participants from the EYO (−35, −13] stage, it may need to last over 10 years to observe significant cognitive decline in the placebo group. Our results hence highlight the necessity of developing more sensitive cognitive tests for prevention trials and more sensitive statistical models to capture the subtle cognitive changes of preclinical AD [10]. Finally, our results will aid future clinical trials to “identify both the stage of AD defined for study eligibility and enrollment and the stage of AD anticipated for the majority of the enrolled patient population at the time of primary outcome assessment”, as recommended in the recent FDA guidance [30].

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size for staging the preclinical ADAD, albeit likely one of the largest, is only moderate for our statistical analyses. A larger sample size will reduce the variability in the estimated EYO cutoffs that defined the preclinical stages. Additionally, the sample size varied by EYO cutoffs, leading to differentially powered statistical tests and differential variability in the estimated EYO cutoffs for stage classification. Second, participants with different genes/mutations were pooled together to determine the preclinical stages due to the limited sample sizes for mutation-specific analyses. This approach warrants caution when generalizing our results to all genes/mutations in ADAD as the natural course of ADAD may depend on the mutation type. Third, the ADAD cohort is much younger than a typical sporadic AD cohort. Differential amyloid deposition rate and multiple pathologies and age-related comorbidities (i.e., vascular) in sporadic AD may undermine the generalization of our results to sporadic AD [31, 32]. Finally, our analytic approach depended on the EYO for asymptomatic MCs. Although relatively highly accurate, the estimates to EYO are not perfect, which may affect the study findings.

In summary, we staged the preclinical ADAD into three stages by the EYO of −13 years and −7 years, and quantified the duration of each preclinical stage. These results are complementary to the existing biomarker-based classification schemes and can assist in determining the cohort and trial duration for primary/secondary prevention trials. The generalizability of our results from ADAD to sporadic AD, however, remains a major challenge.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review: We reviewed existing literature on staging the preclinical stages in autosomal dominant Alzheimer Disease (ADAD) and sporadic AD. No studies have been able to estimate the duration of stages and pinpoint how far they are from the expected symptom onset.

Interpretation: An estimation of the duration of each preclinical stage and how far it is from the expected symptom onset can help prevention AD clinical trials to enroll the right population with an adequate duration.

Future directions: The applicability of our results from ADAD to sporadic AD, i.e., how the preclinical stages as defined by the EYO from mutation carriers may be translated into the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the primary/secondary prevention trials for sporadic AD, remains a major challenge, and a better understanding of the inclusion criteria for prevention trials for sporadic AD warrants further investigation.

Highlights.

We present a novel method to stage the preclinical phase of Alzheimer disease.

Three preclinical stages: EYO (−35, −13], EYO (−13, −7], and EYO (−7, 0).

The stages have potential relevance to the design of prevention AD trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant R01 AG053550 (Dr. Xiong) and NIA grant U19 AG032438 (Dr. Bateman).

Footnotes

Author Disclosures:

The following authors report no disclosures: GW, DB, TLSB, JCM, RJB, CX

EMM- Elli Lilly-Scientific advisory board; UpToDate

JH- Biogen (consultant), Lundbeck (consultant)

AMF- Roche Diagnostics (advisory board), IBL international (advisory board), DiamiR (consultant), AbbVie (consultant), Genentech (advisory board)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia. 2011;7:280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, et al. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;87:539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 2014;13:614–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Xiong C, Jasielec MS, Weng H, Fagan AM, Benzinger TL, Head D, et al. Longitudinal relationships among biomarkers for Alzheimer disease in the Adult Children Study. Neurology. 2016;86:1499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, Bird T, Danek A, Fox NC, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83:253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gordon BA, Blazey TM, Su Y, Hari-Raj A, Dincer A, Flores S, et al. Spatial patterns of neuroimaging biomarker change in individuals from families with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17:241–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, Coats M, Leon S, Sano M, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies the Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study experience. Neurology. 1997;48:1508–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tsubuki S, Takai Y, Saido TC. Dutch, Flemish, Italian, and Arctic mutations of APP and resistance of Aβ to physiologically relevant proteolytic degradation. The Lancet. 2003;361:1957–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang G, Berry S, Xiong C, Hassenstab J, Quintana M, McDade EM, et al. A novel cognitive disease progression model for clinical trials in autosomal‐dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Statistics in medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Storandt M, Balota DA, Aschenbrenner AJ, Morris JC. Clinical and psychological characteristics of the initial cohort of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN). Neuropsychology. 2014;28:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Naveh-Benjamin M Adult age differences in memory performance: tests of an associative deficit hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;26:1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kaplan E Boston diagnostic aphasia examination booklet: Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia, PA; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fisher NJ, Tierney MC, Snow GW, Szalai JP. Odd/even short forms of the Boston Naming Test: Preliminary geriatric norms. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1999;13:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Aschenbrenner AJ, Balota DA, Tse C-S, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Benzinger TL, et al. Alzheimer disease biomarkers, attentional control, and semantic memory retrieval: Synergistic and mediational effects of biomarkers on a sensitive cognitive measure in non-demented older adults. Neuropsychology. 2015;29:368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Armitage SG. An analysis of certain psychological tests used for the evaluation of brain injury. Psychological Monographs. 1946;60:i. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wechsler D WAIS-R manual: Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised. 1981.

- [19].Salthouse TA, Mitchell DR, Skovronek E, Babcock RL. Effects of adult age and working memory on reasoning and spatial abilities. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1989;15:507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Aschenbrenner AJ, Balota DA, Fagan AM, Duchek JM, Benzinger TL, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers moderate baseline differences and predict longitudinal change in attentional control and episodic memory composites in the adult children study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2015;21:573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Huff MJ, Balota DA, Minear M, Aschenbrenner AJ, Duchek JM. Dissociative global and local task-switching costs across younger adults, middle-aged adults, older adults, and very mild Alzheimer’s disease individuals. Psychology and aging. 2015;30:727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Simon JR. Reactions toward the source of stimulation. Journal of experimental psychology. 1969;81:174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Benzinger TL, Blazey T, Jack CR Jr., Koeppe RA, Su Y, Xiong C, et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4502–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in humans. Annals of neurology. 2006;59:512–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Larntz K, Perlman MD. A simple test for the equality of correlation matrices Rapport technique, Department of Statistics, University of Washington: 1985;141. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2014;34:502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982:963–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, Clifford DB, Duggan C, Fagan AM, et al. The DIAN-TU Next Generation Alzheimer’s prevention trial: Adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13:8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ, Grosse E. Regression by local fitting: methods, properties, and computational algorithms. Journal of econometrics. 1988;37:87–114. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Food, Administration D. Draft guidance for industry Alzheimer’s disease: developing drugs for the treatment of early stage disease. Washington, DC: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Young AL, Oxtoby NP, Daga P, Cash DM, Fox NC, Ourselin S, et al. A data-driven model of biomarker changes in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2014;137:2564–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Oxtoby NP, Young AL, Cash DM, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Morris JC, et al. Data-driven models of dominantly-inherited Alzheimer’s disease progression. Brain. 2018;141:1529–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.