Abstract

Heparin is a highly sulfated, complex polysaccharide and widely used anticoagulant pharmaceutical. In this work, we chemoenzymatically synthesized perdeuteroheparin from biosynthetically enriched heparosan precursor obtained from microbial culture in deuterated medium. Chemical de-N-acetylation, chemical N-sulfation, enzymatic epimerization, and enzymatic sulfation with recombinant heparin biosynthetic enzymes afforded perdeuteroheparin comparable to pharmaceutical heparin. A series of applications for heavy heparin and its heavy biosynthetic intermediates are demonstrated, including generation of stable isotope labeled disaccharide standards, development of a non-radioactive NMR assay for glucuronosyl-C5-epimerase, and background-free quantification of in vivo half-life following administration to rabbits. We anticipate that this approach can be extended to produce other isotope-enriched glycosaminoglycans.

Keywords: chemoenzymatic synthesis, deuterated drugs, heparin, pharmacology, stable isotope labeling

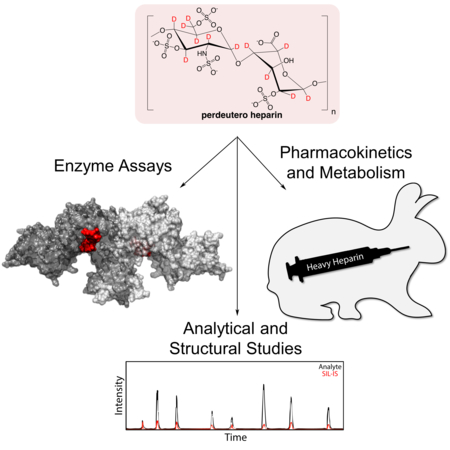

Graphical Abstract

Pushing the envelope of deuterated drug development: Heavy heparin is chemo-enzymatically synthesized from perdeuterated biosynthetic precursor, yielding the most complex stable isotope-enriched pharmaceutical to date. Perdeuterated glycans will be valuable for pharmacological studies, contrast-variation small angle neutron scattering,stimulated Raman scattering imaging, and as internal standards.

Stable isotope labeled (SIL) proteins, nucleic acids, and other biomacromolecules have played essential roles in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small angle neutron scattering structural studies for decades, while labeled small molecules are now central to an array of targeted analytical assays and untargeted metabolomics and proteomics[1]. Recently, the first FDA-approved SIL pharmaceutical with a strategically positioned 2H label entered the market exhibiting improved pharmacological properties[2]. Innovative imaging methodologies have also recently capitalized on SILs as imaging probes[3]. As new methods expand with SIL analogs at their core, synthetic methods to build SIL compounds must co-evolve to keep pace. Our recently demonstrated ability to synthesize bioengineered heparin in multi-mg quantities presents one such opportunity[4].

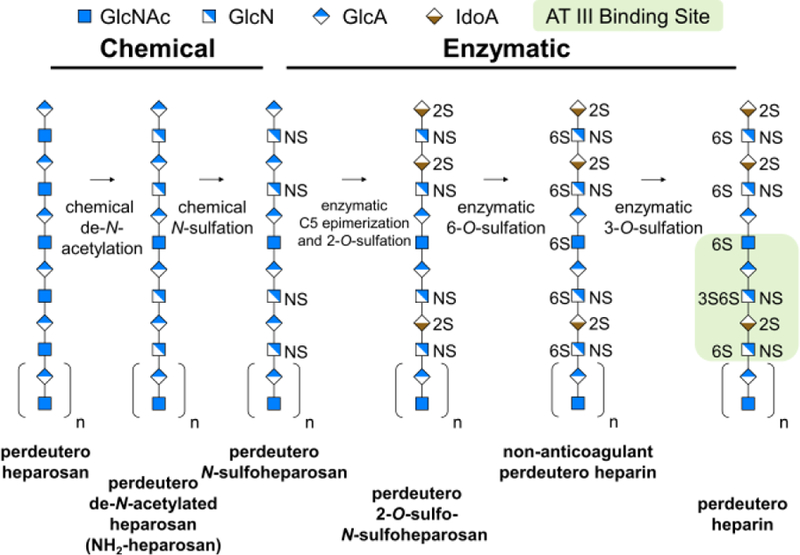

Heparin and structurally related heparan sulfate (HS) glycosaminoglycans are complex, linear, anionic, heterogeneous, polydisperse, polysaccharides comprised of O-sulfated, 1→4 linked repeating units of uronic acid (L-iduronic acid (IdoA) or D-glucuronic acid (GlcA)) and D-hexosamine (N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) or N-sulfoglucosamine (GlcNS))[5]. Heparin/HS biosynthesis, a complex, non-template driven process, involves modification of the heparosan backbone →4)GlcA(1→4)GlcNAc(1→ through de-N-acetylation, N-sulfation, epimerization of GlcA to IdoA, and 2-, 6-, and 3-O-sulfation catalyzed by a suite of biosynthetic enzymes (Supplementary Figure 1 a). Pharmaceutical or unfractionated heparin (UFH), produced by extraction from pig intestine[5], is at risk of contamination and can contain prion and viral impurities[6]. While the chemical synthesis of anticoagulant heparin oligosaccharides, such as Arixtra™[7], is possible, chemical synthesis of UFH is not. We have established a platform for the scalable chemoenzymatic synthesis (Figure 1) of bioengineered heparin for a safe and sustainable supply of synthetic animal-free heparin, that is virtually indistinguishable from UFH [8].

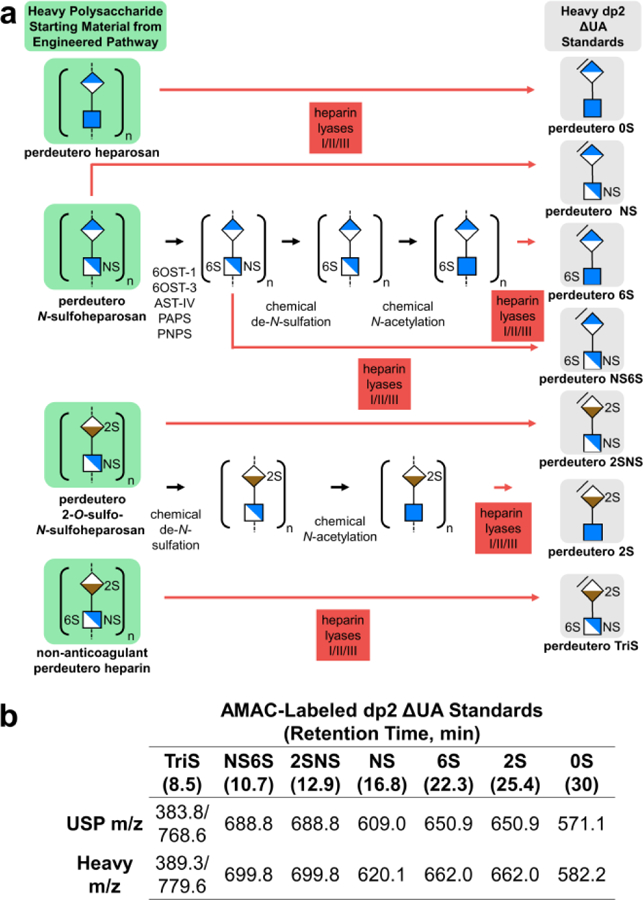

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic isotopic enrichment of chemoenzymatically prepared perdeuteroheparin. A single representative chain of one length and one sequence is shown for illustrative purposes.

The ability to synthesize UFH at scale enables creative control over precise chemical modifications facilitating the development of new heparin products and novel biochemical and pharmacological assays. Selective partial isotopic labeling of UFH was previously reported[9–11]. We chemoenzymatically synthesized small quantities of uniform 13C/15N labeled heparin for NMR studies from the heparosan precursor made by E. coli grown on 13C-glucose and 15NH3[12]. Here we demonstrate the first preparation of stable isotope enriched perdeuteroheparin (“heavy” heparin), from microbially produced perdeuteroheparosan. Small deuterated drug molecules have gained increased interest as 2H labeled molecules can display unique pharmacokinetics (PK)/pharmacodynamics (PD) properties[13–15]. Moreover, 2H labeling permits the highest labeling density for a single stable isotope. In heparin up to 14 non-exchangeable 2H atoms can be incorporated per disaccharide. This work expands the repertoire of perdeuterated natural products and exemplifies a new paradigm in SIL analog synthesis involving the combination of biosynthetic scaffold preparation followed by significant chemoenzymatic modification. Heavy heparin represents the most complex perdeuterated product prepared by synthetic means to date.

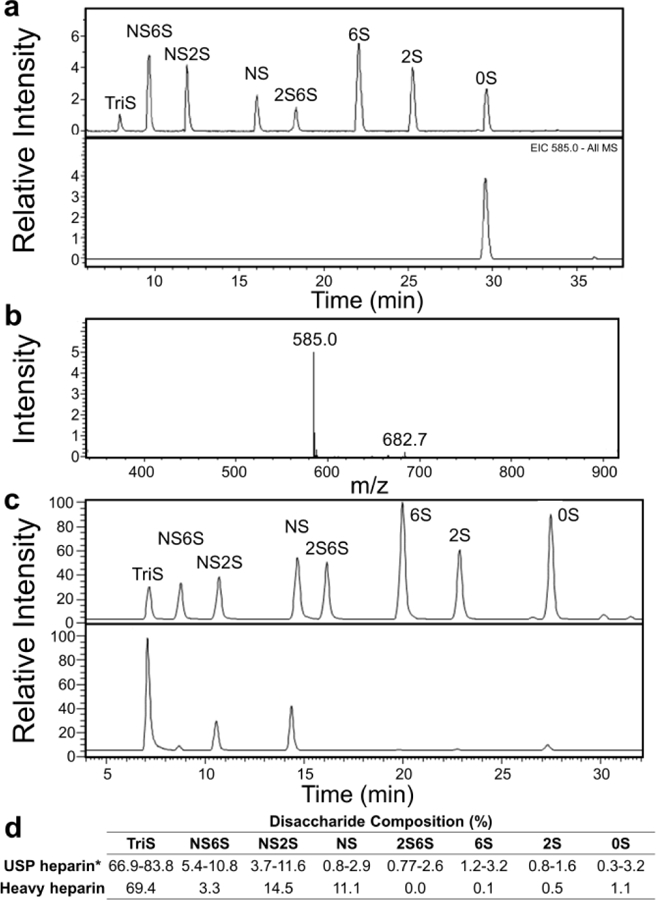

E. coli was used to biosynthesize the perdeuteroheparosan precursor. Preparation of perdeuterated biomolecules by microbes grown in 2H2O containing a perdeuterated carbon source has been reported[16,17]. Perdeuteroheparosan was prepared from E. coli strain ATCC 23506[18], a microbe that naturally produces and sheds this capsular polysaccharide[19], in minimal medium prepared in D2O with heavy glycerol as the sole carbon source. 2H enrichment was significantly enhanced in medium prepared with 2H2O relative to H2O (Supplementary Figure 2). Uniform 2H-labeling precludes analysis by 1H-NMR, so 13C-NMR was used to confirm its structure. Peak assignments were comparable to heparosan standard[20]. Chemical conversion of GlcNAc residues to GlcNS residues was marked by C2 shift to a lower field (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). 2H-NMR further supported 2H incorporation through a characteristic peak at 2 ppm, with CD3 of GlcNAc (Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1). LC-MS analysis of enzymatically depolymerized heavy heparosan and 2-aminoacridone-labeling, yielded a disaccharide correponding to the unlabeled heavy heparosan disaccharide (0S, m/z = 585, 98.6 atm.%) (Figure 3 a,b and Supplementary Figure 2).

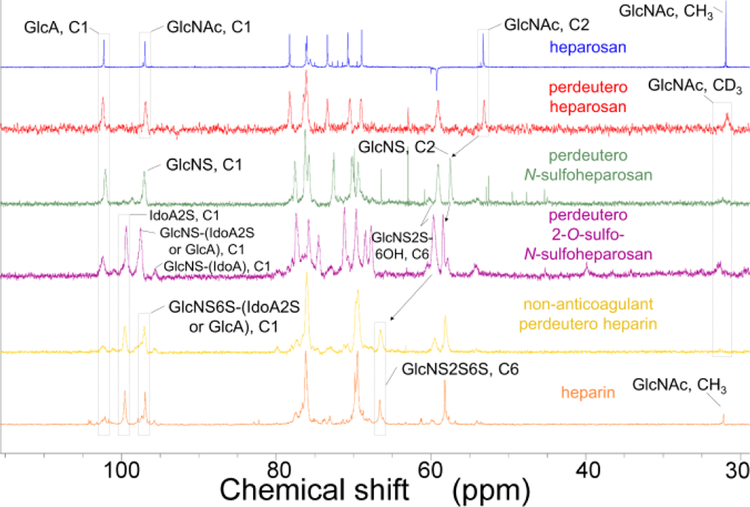

Figure 2.

NMR spectroscopic analysis of perdeuteroheparin and precursors. 13C NMR spectroscopy of products of steps in the chemoenzymatic scheme bracketed by natural heparosan (top, blue) and natural USP heparin (bottom, orange). Perdeuteroheparosan (red), perdeutero-N-sulfoheparosan (green), perdeutero-2-O-sulfo-N-sulfoheparosan (purple), and non-anticoagulant perdeuteroheparin (yellow).

Figure 3.

LC-MS analysis of heavy heparin and precursors. a) Depolymerization of perdeuteroheparosan, followed by 2-aminoacridone labeling, yields a disaccharide matching the retention time of the 0S heparin disaccharide standard (top) with m/z 14 Da greater (bottom), indicating stable 2H incorporation at all 14 non-exchangeable positions. b) MS of perdeuteroheparosan disaccharide indicates high 2H enrichment. c) Disaccharide standards (top) and non-anticoagulant perdeuteroheparin (bottom). d) Disaccharide composition of non-anticoagulant perdeuteroheparin is similar to that of animal derived USP heparin.

Preparation of heparin from microbial heparosan involves two sequential chemical and enzymatic modifications (Supplementary Figure 1). First, perdeuteroheparosan was chemically de-N-acetylated using aqueous NaOH and N-sulfated with (CH3)3N·SO3 to generate heavy N-sulfoheparosan (NSH). LC-MS analysis of heavy NSH disaccharide composition indicated 90 % NAc to NS conversion, supported by near complete loss of 2H signal from GlcNAc C2H3 of the N-acetyl group between the perdeuteroheparosan and heavy NSH 2H spectra. As these reactions were performed in H2O, tautomerization took place at the residual NAc moieties resulting in the transformation of NAc C2H3 to CH3 (treatment of heavy NSH with heparinases generate 0S as m/z = 582). Perdeuteroheparin contains only a very low quantity of NAc-containing disaccharides, thus, this 2H→1H exchange was deemed acceptable, but could be avoided by performing de-N-acetylation in 2H2O and NaO2H.

Simultaneous epimerization (in 2H2O to prevent replacement of C5 2H with 1H) and 2-O-sulfation of this chemically derived intermediate, with E. coli-expressed recombinant glucuronosyl-C5-epimerase (Homo sapiens, Glce) and 2OST-1 (Cricetulus griseus, Hs2st1), yielded perdeutero-2-O-sulfo-NHS. Analysis of heavy C5-epimerized, 2-O-sulfo-NSH by 13C-NMR (Supplementary Table 1) focused on a decrease in the signal for (C2, GlcNS) and (C1, GlcA) and an increase in the signal for (C1, IdoA). The 13C-spectrum for heavy 2-O-sulfo-NSH reveals the nearly complete disappearance of C1 signal from GlcA indicating high levels of epimerization. This intermediate was sulfated through the action of recombinant 6OST-1 (Mus musculus, Hs6st1) and 6OST-3 (M. musculus, Hs6st3) to generate non-anticoagulant heparin with similar disaccharide content as UFH (Figure 3 c,d and Supplementary Table 2). The final heavy heparin product was prepared by treatment of non-anticoagulant perdeuteroheparin with recombinant 3OST-1 (M. musculus, Hs3st1), to generate the antithrombin pentasaccharide-binding site providing anticoagulant activity comparable to heparin. NMR analysis of non-anticoagulant perdeuterated heparin confirmed the generation of a product similar to UFH (Figure 2). In all enzymatic reactions p-nitrophenylsulfate was a sacrificial sulfate donor to regenerate 3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulfate using recombinant arylsulfotransferase-IV (Rattus norvegicus, SULT1A1).

LC-MS quantification of analytes in biological samples is often complicated by variability introduced during sample extraction and preparation of technical and biological replicates. Spiking a SIL-internal standard into a drug prior to administration for PK studies, or even into a biological sample preceding or following analyte extraction, can compensate for this variability. Thus, assays utilizing an appropriate SIL-internal standard are often preferred as their use benefits accuracy, precision, and reproducibility[21]. We prepared perdeuterated heparin disaccharides, as SIL-internal standard for quantification of heparin/HS in biological samples (Figure 4). 2-aminoacridone -labeled perdeuteroheparin disaccharides were confirmed by LC-MS with matched retention times and an appropriate mass increase compared to 2-aminoacridone-labeled UFH disaccharide internal standard (Supplementary Figure 5). Although deuteration has been shown in some cases to alter retention, the 2-aminoacridone-labeled heparin and heavy heparin disaccharides in this study exhibited no significant mobility shifts.

Figure 4.

Heavy heparin disaccharides prepared by enzymatic depolymerization of non-anticoagulant perdeuteroheparin and precursors. a) Chemoenzymatic synthesis and depolymerization scheme for perdeuteroheparin disaccharide standards. Unsaturated uronic acid residues in disaccharide products of heparin lyases I, II, III are indicated with slash at non-reducing end. b) Retention time and m/z of 2-aminoacridone-labeled USP and heavy heparin dp2 standards (Supplementary Fig. 4).

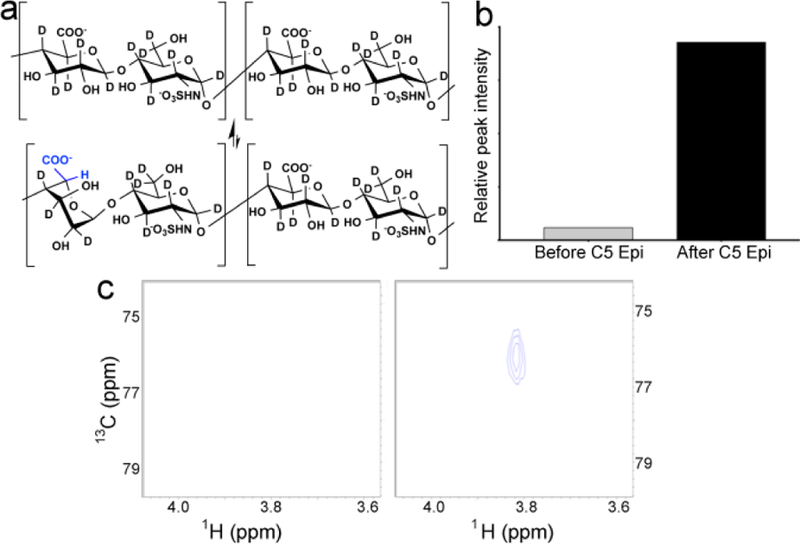

During reversible glucuronosyl-C5-epimerization of the heparin backbone precursor, hydrogen is abstracted from hexuronic acid C5 and replaced by a hydrogen from the solvent (H2O)[22–24]. Quantifying the activity of epimerase presents unique challenges as substrate and product possess the same mass. Moreover, LC-MS assay of disaccharide composition involves heparin lyase-catalyzed depolymerization, generating an unsaturated uronic acid, resulting in a loss of information on C5-epimer identity. Although a direct colorimetric assay for this enzyme does not exist, an indirect colorimetric assay involves a coupled reaction with 2OST[25].

Epimerase activity is often quantified using a radioactive assay involving abstraction of 3H into the solvent from GlcA C5 3H of NSH that has been labeled with 3H at GlcA C5 by reaction with epimerase in 3H2O[9]. Recent reports detail alternative assays utilizing SIL: (1) epimerase treatment of NSH in D2O to site-specifically deuterate GlcA C5, followed by quantification of deuterated disaccharides released by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis[26] and (2) 2D-13C-1H-HSQC-NMR to quantify C5-epimerization of 13C-labeled NSH over time[10].

Treatment of heavy NSH with epimerase in H2O catalyzes the replacement of hexuronic acid 2H with 1H, associated with the conversion of GlcA to IdoA (and subsequent IdoA/GlcA interconversion). Incorporation of C5 H5 in heavy NSH by GlcA C5-epimerization in H2O is easily detected using 2D-1H-13C-HSQC, free from interference due to absence of other 1H atoms in the substrate (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Heavy NSH serves as a substrate in a non-radioactive 2D 1H-13C HSQC NMR epimerase assay. a) Site-specific 1H incorporation at hexuronic acid C5 positions along the heavy NSH chain is achieved by enzymatic GlcA epimerization and subsequent interconversion of GlcA and IdoA residues, reactions involving C5 2H abstraction and replacement by 1H from solvent (H2O). b) Integration of GlcA (C5,H5) peak indicates incorporation of 1H at GlcA C5 following C5 epimerase treatment. c) 1H-13C HSQC spectra of heavy NSH before (left) and after (right) incorporation of 1H at C5 of hexuronic acid by epimerase treatment in H2O.

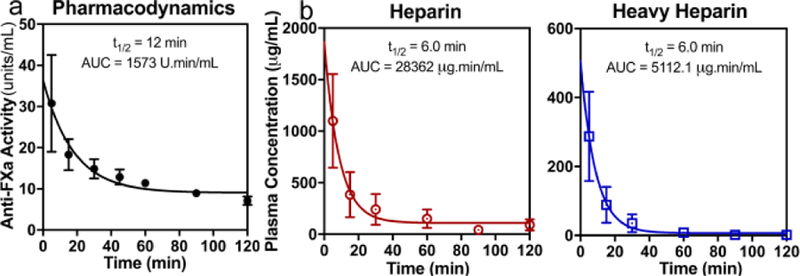

Stable isotope-enriched analogs of biomolecules are easily distinguished from their endogenously biosynthesized counterparts by MS, making these indispensable as exogenously supplied metabolic tracers. However, in quantitative studies, a labeled analog should exhibit similar PK parameters to the natural compound. Given the recent surge of interest in deuterated drugs[27,28], owing to the increased half-lives reported for some heavy analogs, we wondered whether intravenously administered heparin and heavy heparin would exhibit comparable PK parameters. We determined the in vivo half-life of perdeuteroheparin and the unlabeled bioengineered heparin. A mixture of natural abundance and heavy heparin (10 wt%) was administered by intravenous bolus to three rabbits, and the two analogs were quantified in collected plasma samples (Figure 6 a). LC-MS/MS (monitoring heparin’s major disaccharide component, TriS[29]) was used to directly detect and quantify isotopolog concentrations in plasma over time (Supplementary Figure 4). The anticoagulant activity of administered heparin mixture in plasma was quantified by anti-factor Xa activity assay as a measure of PD (Figure 6 a).

Figure 6.

Time course of drug clearance from plasma following intravenous heparin administration (mixture of 90% natural abundance and 10% perdeuterated by mass) to rabbits. a) PD: Anti-factor Xa activity of heparin and perdeuteroheparin mixture in plasma quantified over time. b) PK: heparin (red circles) and perdeuteroheparin (blue squares) concentration in plasma over time as quantified by MRM LC-MS/MS. Symbols and error bars are mean and SEM of biological triplicates. Lines show fit of first order decay to mean values, where calculated half-life and area under the curve (AUC) values are reported.

The 6 min half-lives for heparin and heavy heparin (Figure 6 b) were idential and comparable to literature values[30]. Notably, oxidatively metabolized drugs often exhibit accelerated in vivo degradation relative to their deuterated counterparts due to large 2H kinetic isotope effects[27]. Since heparin is thought to be cleared from the circulation through a non-oxidative mechanism[31], it was not surprising that perdeuteration did not confer a prolonged plasma half-life. Thus, heavy heparin can be used as a surrogate for heparin in animal studies.

Heparin is among the most widely used pharmacological agents and, along with HS, is an important endogenous regulator of multiple biological pathways[32]. Thus, heavy heparin and its intermediates should provide a better understanding of heparin/HS biological activities. In NMR spectroscopy and small angle neutron scattering, heavy heparin should be a useful binding partner for the structural biology studies of heparin-binding proteins[33]. In addition, stimulated Raman scattering imaging examines a silent region in the Raman spectrum that is only excited when C-2H bonds are stimulated, allowing high-resolution, real-time imaging of 2H labeled metabolites in tissue slices and cells[3,32]. Thus, heavy heparin and potentially heavy HS should enhance our understanding of the critical roles of these glycans by facilitating the development of new analytical approaches making use of SIL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (CA231074, HL125371, and HL094463) and the National Science Foundation (MCB-1448657 and CBET-1604547). The authors thank Dr. G. Li, X. Sun, and L. Lin for analytical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Brady F. Cress, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA).

Dr. Ujjwal Bhaskar, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA).

Deepika Vaidyanathan, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA).

Asher Williams, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA).

Dr. Chao Cai, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Dr. Xinyue Liu, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Dr. Li Fu, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Dr. Vandhana M-Chari, PRI, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 106 New Scotland Ave., Albany, NY, 12208 (USA); Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 106 New Scotland Ave., Albany, NY, 12208 (USA)

Dr. Fuming Zhang, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Prof. Shaker A. Mousa, PRI, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 106 New Scotland Ave., Albany, NY, 12208 (USA); Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 106 New Scotland Ave., Albany, NY, 12208 (USA)

Prof. Jonathan S. Dordick, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Biological Sciences, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Prof. Mattheos A. G. Koffas, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Biological Sciences, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA)

Prof. Robert J. Linhardt, CBIS, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Biological Sciences, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA); Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, RPI, 110 8th St., Troy, NY 12180 (USA).

References

- [1].Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Siuzdak G, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2016, 17, 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schmidt C, Nat. Biotechnol 2017, 35, 493–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wei L, Yu Y, Shen Y, Wang M, Min W, PNAS 2013, 110, 11226–11231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bhaskar U, Li G, Fu L, Onishi A, Suflita M, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ, Carbohydr. Polym 2015, 122, 399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Linhardt RJ, in J Med. Chem, 2003, pp. 2551–2564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [6].Liu H, Zhang Z, Linhardt RJ, Nat. Prod. Rep 2009, 26, 313–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Petitou M, Van Boeckel CAA, Angew. Chemie -Int. Ed 2004, 43, 3118–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu J, Linhardt RJ, Nat. Prod. Rep 2014, 00, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Campbell P, Hannesson HH, Sandbäck D, Rodén L, Lindahl U, Li JP, J. Biol. Chem 1994, 269, 26953–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Préchoux A, Halimi C, Simorre J-P, Lortat-Jacob H, Laguri C, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pomin VH, Sharp JS, Li X, Wang L, Prestegard JH, Anal Chem 2010, 82, 4078–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang Z, McCallum SA, Xie J, Nieto L, Corzana F, Jiménez-Barbero J, Chen M, Liu J, Linhardt RJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 12998–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Timmins GS, Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 2014, 24, 1067–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Davey S, Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 368–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gupta M, Zha J, Zhang X, Jung GY, Linhardt RJ, Koffas MAG, ACS omega 2018, 3, 11643–11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Meilleur F, Weiss KL, Myles DAA, Methods Mol. Biol 2009, 544, 281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moulin M, Strohmeier GA, Hirz M, Thompson KC, Rennie AR, Campbell RA, Pichler H, Maric S, Forsyth VT, Haertlein M, Chem. Phys. Lipids 2018, 212, 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cress BF, Greene ZR, Linhardt RJ, Koffas MAG, Genome Announc 2013, 1, 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cress BF, Englaender J. a., He W, Kasper D, Linhardt RJ, Koffas MAG, FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2014, 38, 660–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang Z, Ly M, Zhang F, Zhong W, Suen A, Hickey AM, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ, Biotechnol. Bioeng 2010, 107, 964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Matuszewski BK, Constanzer ML, Chavez-Eng CM, Anal. Chem 2003, 75, 3019–3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lindahl U, Jacobsson I, Höök M, Backström G, Feingold DS, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1976, 70, 492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jensen J, Campbell P, Rodén L, Jacobsson I, Bäckström G, Lindahl U, Glycoconjugate Res 1979, II, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Prihar HS, Campbell P, Feingold DS, Jacobsson I, Jensen JW, Lindahl U, Roden L, Biochemistry 1980, 19, 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sterner E, Li L, Paul P, Beaudet JM, Liu J, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2014, 406, 525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Babu P, Victor XV, Nelsen E, Nguyen TKN, Raman K, Kuberan B, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2011, 401, 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gant TG, J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 3595–3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Katsnelson A, Nat. Med 2013, 19, 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Capila I, Linhardt RJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2002, 41, 391–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Boneu B, Caranobe C, Gabaig AM, Dupouy D, Sie P, Buchanan MR, Hirsh J, Thromb. Res 1987, 46, 835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Palm M, Mattsson Ch., Thromb. Haemost 1987, 58, 932–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Long R, Zhang L, Shi L, Shen Y, Hu F, Zeng C, Min W, Chem. Commun 2017, 152–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [33].Rubinson KA, Chen Y, Cress BF, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Biopolymers 2016, 105, 905–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.