Abstract

Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) mediates oligomeric amyloid-β peptide (oAβ)-induced oxidative and inflammatory responses in glial cells. Increased activity of cPLA2 has been implicated in the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), suggesting that cPLA2 regulation of oAβ-induced microglial activation may play a role in the AD pathology. We demonstrate that LPS, IFNγ, and oAβ increased phosphorylated cPLA2 (p-cPLA2) in immortalized mouse microglia (BV2). Aβ association with primary rat microglia and BV2 cells, possibly via membrane-binding and/or intracellular deposition, presumably indicative of microglia-mediated clearance of the peptide, was reduced by inhibition of cPLA2. However, cPLA2 inhibition did not affect the depletion of this associated Aβ when cells were washed and incubated in a fresh medium after oAβ treatment. Since the depletion was abrogated by NH4Cl, a lysosomal inhibitor, these results suggested that cPLA2 was not involved in the degradation of the associated Aβ. To further dissect the effects of cPLA2 on microglia cell membranes, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to determine endocytic activity. The force for membrane tether formation (Fmtf) is a measure of membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity and represents a mechanical barrier to endocytic vesicle formation. Inhibition of cPLA2 increased Fmtf in both unstimulated BV2 cells and cells stimulated with LPS + IFNγ. Thus, increasing p-cPLA2 would decrease Fmtf, thereby increasing endocytosis. These results suggest a role of cPLA2 activation in facilitating oAβ endocytosis by microglial cells through regulation of the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity.

Keywords: Aβ clearance, Alzheimer’s disease, cytosolic phospholipase A2, membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity, microglia

Introduction

Growing evidence has shown an important role of microglia in sporadic or late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) [1], In addition, increased cytosolic phospholipase A2(cPLA2) activity has been observed in AD brains [2,3], although the roles of this enzyme in the pathological expression in AD is not fully understood. The goal of this study is to examine the role of cPLA2 in soluble oligomeric Aβ (oAβ) association with microglial cells.

As the resident macrophage cells, microglia are key cells responsible for scavenging cell debris, plaques, and damaged neurons and synapses in the brain [4], In recent years, understanding the mechanism(s) for the microglia-mediated clearance of Aβ has become an important direction of AD research. Aβ phagocytosis by microglia has been shown to be governed by a range of receptors [5]. For example, macrophage scavenger receptor 1 (SCARA1) [6,7], CD36 [8-10], and a functional triggering receptor expressed on the myeloid cells 2 protein (TREM2) [11-14] facilitate Aβ uptake. However, some receptors, such as the CD14-Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [15,16], and CD33, a member of the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (SIGLECS) family [17,18], reduce the ability to phagocytose Aβ. Although receptor-mediated Aβ phagocytosis has been extensively studied, how Aβ-triggered cellular pathways that determine oAβ uptake by microglia are still not fully understood.

Although increased cPLA2 activity has been implicated in AD [2] and Aβ has been shown to activate cPLA2in microglia [2,19,20], the role of cPLA2 in alterations of microglial functions related to AD pathophysiology are not fully understood. There is evidence showing oAβ causes cellular membranes to become more molecularly-ordered in astrocytes, and this process involves activation of cPLA2 [19]. cPLA2 has also been found to mediate actin rearrangements [21,22]. Since endocytosis is both a biochemical and a mechanical process (i.e. mechanochemical processes) governed in parts by the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity [23], we further tested the hypothesis that cPLA2 plays a role in endocytosis of oAβ in microglia through its effects on membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity.

In this study, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of cPLA2 in microglial cells is essential in maintaining oAβ association with microglial cells, possibly via membrane-binding and/or intracellular deposition. However, cPLA2 activation is not involved in the degradation of the associated Aβ in microglia. Our study using cPLA2 inhibitors and atomic force microscopy (AFM) shows that inhibiting cPLA2 activation results in elevated force for membrane tether formation (Fmtf), which is a measure for the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity, and represents a mechanical barrier to endocytic vesicle formation. These data suggest that cPLA2 facilitates oAβ association with microglia in part through the regulation of the cell membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Human Aβ42 was purchased from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA). Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail, PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), and Triton X-100 were purchased from MilliporeSigma (St. Louis, MO). Ham’s F-12 was from Crystalgen Inc. (Commack, NY). Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM), Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S), and Dulbecco’s Phosphate-buffered Saline (DPBS) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from GE Healthcare Life Science (Logan, UT). Methylarachidonyl fluorophosphate (MAFP), pyrrophenone (Pyr), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and bromoenol lactone (BEL) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Recombinant mouse and rat interferon gamma (IFNγ) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA buffer), BCA protein assay kit, ProLong™ diamond antifade mountant with DAPI, SuperSignal™ west femto maximum sensitivity substrate, SuperSignal™ west pico plus chemiluminescent substrate, and Restore™ PLUS western blot stripping buffer were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Paraformaldehyde (PFA), tween® 20, and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Laemmli sample buffer and tris buffered saline (TBS) were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

Preparation of Oligomeric Aβ.

Oligomeric Aβ42 (oAβ) was prepared according to the protocol as described by Dahlgren et al. 2002 [24].

Primary Rat Microglia Isolation.

All protocols involving the use of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and primary cortical microglia were isolated as described [25]. A neural tissue dissociation kit (P) from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA) was used to re-suspend cells [26]. Primary microglia were isolated using CD1 lb/c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Primary Rat Microglial Cell Culture.

Primary rat microglia were seeded onto a 6-well plate after isolation with a density of 5× 105 cells per well and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS and 1% P/S. Cells were treated after two days of culturing.

BV2 Cell Culture.

The immortalized mouse microglia cell line, BV2 cells, were provided by Dr. Rosario Donato (University of Perugia, Italy). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with 10% HI-FBS and 1% P/S (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin). At 80-90% confluency, BV2 cells were detached from the culture flasks with a cell scraper and re-seeded (~105 cells) in new T-75 flasks. Cells were used between passages 15-25.

Measurement of Aβ association with cells.

Primary rat microglia were cultured in 6-well plates and incubated with serum free DMEM for 1 h before treatments. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM MAFP or Pyr for 30 min and remained in the medium. Cells were then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1μM oAβ for 1h. BV2 cells were cultured in 35 mm dishes to a confluence of 70-80% and incubated with serum free DMEM for 6 h. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM MAFP or Pyr or 2 μM BEL for 30 min and remained in the medium thereafter. Cells were then stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS +10 ng/ml IFNγ for lh, followed by incubation with 1 μM oAβ for 15, 30, 45 or 60 min. Cells were washed, lysed and collected using RIPA buffer supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Total protein concentrations were determined with BCA kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ELISA assay of human Aβ42 (Life Technologies) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were represented as the total amount of Aβ divided by the total protein per sample (pg Aβ/μg total protein) and normalized by control groups (i.e. Cells treated with oAβ alone or LPS + IFNγ + oAβ).

Western Blot Analysis.

Cells were cultured in 35 mm dishes at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL overnight achieve 70-80% confluence. Before treatment, BV2 cells were starved with serum free media for 6h. Cells were stimulated with 1 μM oAβ for lh, 0.1 or 1 μg/mL LPS and/or 10 ng/mL IFNγ for various time points to identify the time course for activation of cPLA2. After treatment, cells were washed twice with cold DPBS and then lysed with 300 μL cold RIPA buffer supplemented with cOmplete protease and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktails for 15 min at 4 °C. Cell lysates were collected into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes by a cell scraper. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and supernatants were collected. Western blot analysis of p-cPLA2 was carried out as previously described [26].

Measurement for the Depletion of Associated Aβ with Cells by ELISA Assay.

BV2 cells were starved in serum free DMEM for 6 h and pretreated with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ ml IFNγ for 1 h or 20 mM NH4Cl for 30 min. Cells were then treated with 1 μM oAβ for 15 min and replaced with serum-free DMEM. At time 0, the cells were either collected or further incubated for 5, 15, 30 or 60 min in the presence of 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ ml IFNγ, 10 μM MAFP, 10 μM Pyr, 2 μM BEL or 20 mM NH4Cl before cell lysis. Total protein and Aβ quantification analysis was performed in the same manner as the previous section, “Measurement of Aβ Association with cells”.

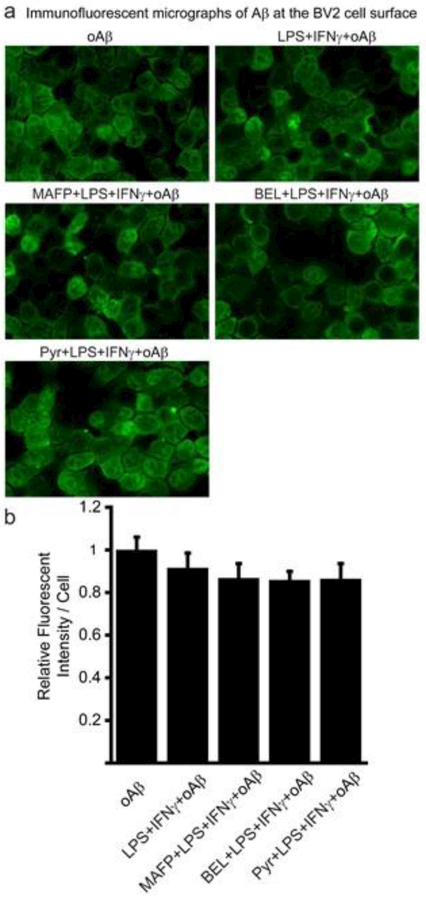

Immunofluorescence Microscopy of Aβ at the Cell Surface.

Cells were grown on poly-D-lysine pre-coated coverslips in 12-well plate to a density of 8× 104 or 5× 104 cells/well respectively overnight in culture medium. In the next day, cells underwent the aforementioned treatments with LPS, IFNγ, 10 μM MAFP or Pyr, BEL and/or Aβ42. After treatment, cells were washed twice with cold DPBS and fixed with 3.7% PFA in DPBS for 15 min. Cells were washed 3 times with DPBS and then blocked with 5% BSA (w/v) in DPBS for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-6E10 (BioLegend, Dedham, MA, 1:200) in 1% BSA in DPBS at 4°C overnight in dark then washed 3 times with DPBS and mounted onto slides with ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI and cured at room temperature in dark for 24 h before imaging. Fluorescent images were acquired by a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope with an oil immersion 60X objective lens using a CCD camera. At least 12 images were acquired from each sample. Analysis was performed with CellProfiler software (Carpenter Lab at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT) and data was normalized by the cell number.

Mass Conservation for Aβ42 in BV2 Cell Culture.

To quantify p-cPLA2 mediated uptake and processing of Aβ within microglia, a simple analytical equation was developed based on the principle of mass conservation. The rate of change of intracellular concentration of Aβ can be defined as

| (1) |

, where kup is the Aβ uptake rate constant, kd the Aβ depletion rate constant, Ci the intracellular concentration of Aβ, and Co the concentration of Aβ in the medium. In this model, the following assumptions are made: 1) Co is considered constant, since Co » Ci ; and 2) kd is considered to be constant because the depletion of the intracellular Aβ was not affected by cPLA2 inhibition via MAFP treatment (Fig. 5b). By defining the relative intracellular Aβ concentration, , with an initial condition, , solving Eqn. 1 yields:

| (2) |

Fig. 5.

Depletion of associated Aβ in BV2 cells. (a) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells treated with NH4Cl using ELISA assay. BV2 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 1 h or 20 mM NH4Cl for 30 min, followed by adding 1 μM oAβ for 15 min. Afterwards the media was replaced with standard serum-free media and allowed to incubate for 5, 15, 30 and 60 min before lysis. In the case of the 0 min treatment groups, the cells were immediately lysed after incubating cells with 1 μM oAβ for 15 min. Data are represented as the ratios of Aβ to total protein, and normalized by the oAβ group at 0 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments (n ≥ 3). ***P<0.001 compared with the oAβ group at 0 min; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 compared with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group. (b) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells treated with MAFP, BEL or Pyr using ELISA assay. BV2 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS +10 ng/mL IFNγ for 1 h, followed by 1 μM oAβ incubation for 15 min. Afterwards, cells were treated with serum-free media, 10 μM MAFP, 10 μM Pyr or 2 μM BEL for 5, 15, 30 and 60 min before cell lysis. Data are represented as the ratio of Aβ42 to total protein, and normalized by the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at 0 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments (n ≥ 3).

Definitions and units of all parameters in this mass conservation-based model are provided in Table 1. Fitting data from Fig. 4b with Eqn. 2 yields for different concentrations of MAFP (Fig. 6a). Plotting against MAFP concentration exhibits a negative linear relationship between and MAFP concentration (Fig. 6b). Since Fig. 5b suggested kd was not changed by MAFP, kup decreased linearly with increasing dose of MAFP.

Table. 1.

Defining the variables of the mass conservation-based model.

| Variable | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Ci | Concentration of Aβ associated in the cell | pg Aβ/μg total protein |

| Co | Concentration of oAβ in medium | μM oAβ |

| The ratio of Aβ in the cell to oAβ in medium (Ci/Co) |

(pg Aβ/μg total protein)/(μM oAβ) | |

| kup | oAβ uptake rate constant | (pg oAβ/μg total protein)/(μM Aβ)(min) |

| kd | Aβ depletion rate constant | (min−1) |

| kup.Co | Rate of oAβ uptake | (pg oAβ/μg total protein)/(min) |

| kd.Ci | Rate of Aβ depletion | (pg Aβ/μg total protein)/(min) |

| dCi/dt | Rate of change of associated Aβ concentration in the cell |

(pg Aβ/μg total protein)/(min) |

| t | Time | min |

Fig. 4.

Aβ association with BV2 cells surface. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 μM MAFP or Pyr or 2 μM BEL for 30 min and treated with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 1 h, followed by incubation with 1 μM oAβ for 15 min. Fluorescent intensities per cell were normalized by the oAβ group. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3) (at least 12 images were analyzed for each group per experiment). * P < 0.05 compared with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group. (a) Representative immunofluorescent images of Aβ association with BV2 cell surface. Aβ was stained with Alexa Fluor 488-6E10 antibody without cell permeabilization. (b) Quantification of immunofluorescent images of Aβ association with BV2 cell surface. MAFP and Pyr did not impose any effect on Aβ association with BV2 cell surface.

Fig. 6.

Application of the mass conservation model to the experimental ELISA Aβ association with BV2 cells data. (a) Normalized concentration of Aβ in cells, , from Fig. 4B were plotted against time and fit with a mathematical model, , to yield the ratio of the oAβ uptake rate constant to the Aβ depletion rate constant (kup/kd) for different doses of MAFP. (b) The ratio of the oAβ uptake rate constant to Aβ depletion rate constant (kup/kd) linearly decreased with increasing dose of MAFP. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM.

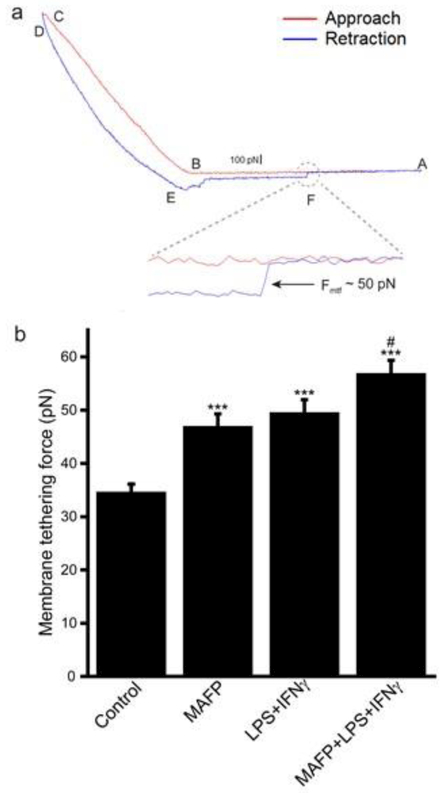

Membrane Tethering Force Measurement.

BV2 cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine pre-coated coverslips. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM MAFP or without for 30 min and then treated with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 1 h. Then the coverslip was washed with PBS and mounted onto a glass slide with Epoxy (3M, St. Paul, MN), cells were kept wet during all the procedures. Tethering forces were measured using a MFP-3D Bio atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Oxford Instruments Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). TR400PSA cantilevers (also known as OTR4, Oxford Instruments Asylum Research) were used. Spring constant of the AFM tips were range from 82.69 to 100.24 pN/nm. Indentation for each measurement is 1 μm with a rate of 1 Hz and the force curve for each measurement was recorded by the software (AR14, Oxford Instruments Asylum Research). At least 10 cells and 5 force curves per cell were analyzed for each group.

Statistical Analysis.

Data is presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests in GraphPad Prism (Version 6.01). P-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Results

cPLA2 Inhibitors Decrease Aβ Association with Primary Rat Microglia.

As compared to the monomeric and fibrillar forms of Aβ, oAβ has been reported to be the most neurotoxic form of aggregates [24]. In this study, we focus on oAβ association with microglia. oAβ was prepared as previously described [24] and was characterized using AFM for quality control as previously described [27]. To demonstrate the role of cPLA2 in the association of oAβ with microglia, primary rat microglia were pretreated with cPLA2 inhibitors, MAFP and Pyr, followed by treatment with 1μM oAβ for lh. Aβ association with cells was assessed using ELISA. Pre-stimulation of cells with LPS + IFNγ, known to activate cPLA2, did not increase Aβ association with cells (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, both Pyr and MAFP decreased Aβ association with primary rat microglia (Fig. 1a), suggesting a role for cPLA2 in Aβ association with microglia. However, when we performed fluorescent immunostaining of Aβ without cell permeabilization (i.e. fluorescently labeling Aβ at the cell surface only), both cPLA2 inhibitors did not affect Aβ association with primary rat microglia at the cell surface (Fig. 1b and c). These results suggest that cPLA2 inhibitors decrease oAβ internalization in primary microglia.

Fig. 1.

Aβ association with primary rat microglia. (a) Quantification of Aβ association with primary rat microglia using ELISA assay. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 μM Pyr or MAFP for 30 min, followed by treatment with 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ for 1 h, and then cells were exposed to 1 μM oAβ for 1 h. Data are represented as the ratio of Aβ to total protein, and normalized by the control group (oAβ group). Data are shown as mean ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments (n ≥ 3). *** P < 0.001 comparing with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group. (b) Representative immunofluorescent images of Aβ association with primary rat microglia at the cell surface. Aβ was stained with Alexa Fluor 488-6E10 antibody without cell permeabilization. (c) Quantification of immunofluorescent images of Aβ association with primary rat microglia at the cell surface. MAFP and Pyr did not impose any effect on Aβ association with primary rat microglial cell surface.

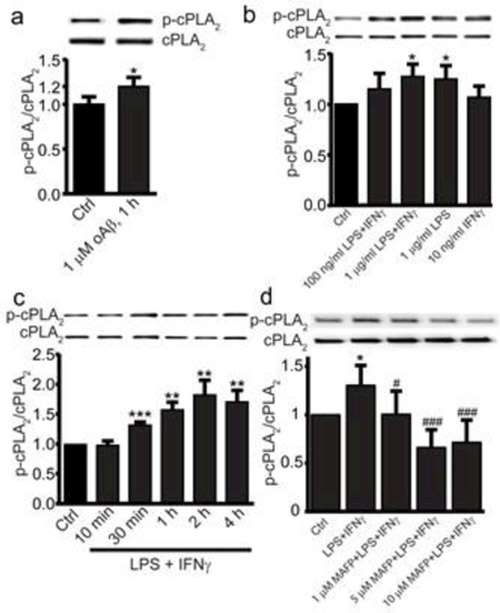

Activation of cPLA2 in BV2 cells by oAβ and LPS + IFNγ.

To further study the roles of cPLA2 in Aβ association with microglia, we utilized immortalized mouse microglia (BV2 cells). BV2 cells are the most frequently used cell lines in studies of microglia and have been shown to demonstrate similar inflammatory responses and Aβ accumulation to primary microglia [28,29,26]. Here we demonstrate the activation of cPLA2 in BV2 cells. When BV2 cells were exposed to 1μM oAβ for lh, activation of cPLA2 was reflected by the increase in phosphorylated cPLA2 (p-cPLA2) (Fig. 2a). cPLA2 was also activated when cells were exposed to 1μg/mL LPS + 10ng/mL IFNγ and 1γg/mL LPS for 1 h (Fig. 2b). When cells were exposed to 1γg/mL LPS + 10ng/mL IFNγ, the increase in p-cPLA2 was activated in a time-dependent manner with a maximal activation after 2h (Fig. 2c). p-cPLA2 was suppressed when cells were pretreated with MAFP for 30 min (Fig. 2d). Based on these results, BV2 cells were stimulated with 1 γg/mL LPS + 10ng/mL IFNγ for 1 h, and different concentrations (5 and 10 μM) of MAFP were applied to further study the role of cPLA2 in oAβ association with microglia.

Fig. 2.

CPLA2 activation in BV2 cells. Cells were treated with (a) 1 μM oAβ42 for 1 h, (b) LPS and/or IFNγ (10 ng/ml in all cases except control) for 1 h and (c) 1 μg/mL LPS and 10 ng/mL IFNγ from 0-4 h. (d) BV2 cells were pretreated with 0, 1, 5 or 10 μM MAFP for 30 min, then all groups were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) + IFNγ (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. The ratio of p-cPLA2/cPLA2 is represented as the fraction percentage of the control group. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3-4 independent experiments (n = 3 or 4), at least 6 independent experiments for (d) (n ≥ 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the control group; # P < 0.05, ### P < 0.001 compared with the LPS + IFNγ group in (d).

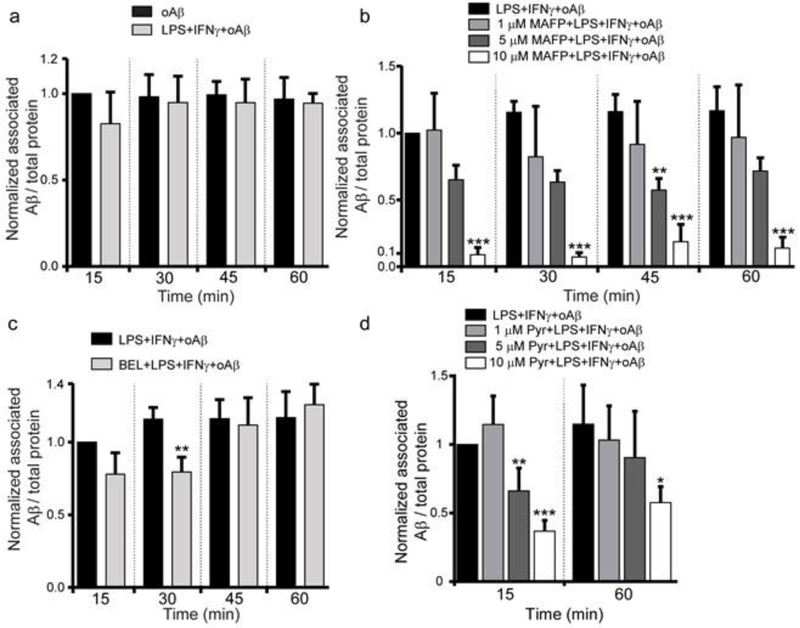

cPLA2 Inhibitors Decreases Aβ Association with BV2 cells.

Consistent with the results using primary rat microglia (Fig. 1a), we found that pre-stimulation of BV2 cells with LPS + IFNγ did not increase Aβ association with cells (Fig. 3a). Inhibition of cPLA2 with MAFP and Pyr decreased Aβ association with BV2 cells (Fig. 3b and d). MAFP and Pyr did not affect Aβ association with BV2 cells at the cell surface (Fig. 4a and b). These results suggest that inhibition of cPLA2 by MAFP and Pyr reduced Aβ association with microglia, and that mainly occurred intracellularly. Since MAFP at high concentrations can also inhibit calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), we found that BEL, a specific iPLA2 inhibitor, also had no effect on Aβ association with cells (Fig. 3c), thus ruling out the involvement of iPLA2.

Fig. 3.

Effect of CPLA2 inhibition on Aβ association with BV2 cells. (a) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells pre-treated with LPS + IFNγ using ELISA assay. Cells were treated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml) + IFNγ (10 ng/ml) for 1 h, followed by 1 μM oAβ42 treatment for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. Data are represented as the ratio of Aβ42 to total protein, and normalized by the oAβ group at 15 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3). No significant difference was observed between these two groups at any time point. (b) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells pre-treated with MAFP using ELISA assay. Cells were pretreated without or with MAFP (1 μM, 5 μM and 10 μM) for 30 min, followed by 1 μg/ml LPS +10 ng/ml IFNγ treatment for 1 h, then cells were incubated with 1 μM oAβ for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. Data are represented as the ratio of Aβ to total protein, and normalized by the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at 15 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at the corresponding time. (c) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells pre-treated with BEL using ELISA assay. Cells were pretreated without or with 2 μM BEL for 30 min, followed by 1 μg/ml LPS +10 ng/ml IFNγ treatment for 1 h, then cells were incubated with 1 μM oAβ for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. Data is represented as the ratio of Aβ to total protein, and normalized by the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at 15 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3). ** P < 0.01 compared with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at the corresponding time. (d) Quantification of associated Aβ in BV2 cells pre-treated with Pyr using ELISA assay. Cells were pretreated without or with Pyr (1 μM, 5 μM and 10 μM) for 30 min, followed by 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ treatment for 1 h, then cells were incubated with 1 μM oAβ for 15 and 60 min. Data is represented as the ratio of Aβ to total protein, and normalized by the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at 15 min. Data are shown as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (n = 3). *P<0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with the LPS + IFNγ + oAβ group at the corresponding time.

Fig. 3a also suggests that intracellular Aβ content had already reached equilibrium after exposing cells to oAβ for 15 min. However, Aβ association with cells was decreased by MAFP and Pyr in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3b and d). These results suggest that an equilibrium of associated Aβ was reached within 15 min, when the rate of oAβ uptake equaled the rate of Aβ depletion in cells. Inhibition of cPLA2 by MAFP and Pyr decreased Aβ association with cells, indicating a shift of this equilibrium.

Inhibition of cPLA2 does not Affect Depletion of Associated Aβ in BV2 Cells.

Aβ association with cells is governed by both the rates of oAβ uptake and depletion of associated Aβ. Although the rate of oAβ uptake cannot be measured directly, it can be indirectly evaluated by measuring both oAβ association with cells (Fig. 3) and the depletion of associated Aβ in cells (Fig. 5). To study the depletion of associated Aβ in BV2 cells, cells stimulated by LPS + IFNγ were exposed to 1μM oAβ for 15 min, followed by replacing oAβ-containing media with standard serum-free media. Cells were then incubated in standard serum-free media for 5, 15, 30 and 60 min and lysed to quantify associated Aβ in cells using ELISA. Fig. 5a shows that pre-stimulation of cells with LPS + IFNγ did not affect depletion of associated Aβ. Associated Aβ decreased and leveled off at ~35% within 5 min and remained unchanged even at the 60-min time point (Fig. 5a). The depletion of associated Aβ can be the result of Aβ recycling back to the media and/or hydrolysis of Aβ in lysosomes. To examine the cause of associated Aβ depletion, we treated cells with 20 mM NH4Cl, an inhibitor of lysosomal function [30-32] after the treatment of cells with oAβ. We found that the depletion of associated Aβ was completely abrogated in cells pretreated with NH4Cl (Fig. 5a). These results indicate that degradation of associated Aβ in lysosomes is the major cause of the depletion of associated Aβ in cells. MAFP, Pyr and BEL did not impose any effects on the depletion of associated Aβ (Fig. 5b), indicating that neither cPLA2 nor iPLA2 plays a role in the degradation of associated Aβ.

Inhibition of cPLA2 Decreases the oAβ Uptake Rate Constant.

Since cPLA2 did not affect the rate of associated Aβ depletion in cells (Fig. 5b), data depicting the effects of cPLA2 inhibition on Aβ association with cells in Fig. 3b suggest that oAβ uptake rate constant decreases with increasing dose of MAFP. By applying the principle of conservation of mass (see detailed derivation in the Methods section), the normalized concentration of associated Aβ in cells, , at different time points can be fit with a mathematical model, , to yield the ratio of the oAβ uptake rate constant to the Aβ depletion rate constant, , for different doses of MAFP (Fig. 6a). Plotting against the concentration of MAFP, showing that decreased linearly with an increasing dose of MAFP (Fig. 6b). Since Fig. 5b suggests that kd was independent of cPLA2 activation (i.e. kd remained unchanged with different dose of MAFP), Fig. 6b suggests that the oAβ uptake rate constant, kup, decreased linearly with an increasing dose of MAFP.

Inhibition of cPLA2 Increases the Membrane-Cytoskeleton Connectivity.

Membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity governs many mechanochemical processes [23], including endocytosis [23,33,34], Membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity can be quantitatively evaluated by the measurement of force for membrane tether formation (Fmtf) using laser tweezers [33,35,36] and atomic force microscopy (AFM) [37,38], Here, we employed AFM to study the mechanical process underlying the effects of cPLA2 inhibition on oAβ association with BV2 cells. Fig. 7a is a typical force curve obtained from AFM measurement. The red curve represented the AFM cantilever approaching to the cell in three steps: (1) the cantilever was approaching to the cell without contact from A to B; (2) the cantilever contacted the cell surface at B; (3) the cantilever moved further to make an indentation from B to C (Fig. 7a). The red curve from B to C, where cell indentation was made, is typically fitted with the Hertz model to estimate cell stiffness, which is not the focus of this study. The blue curve represented the cantilever retracting from the cell (Fig. 7a). Along the retraction curve, a sudden release of force was observed at point F, where the rupture of a membrane tether occurred (Fig. 7a). The step change in the force curve during the rupture of a membrane tether was used to measure Fmtf. Fig. 7b showed that MAFP increased Fmtf in unstimulated cells and in cells stimulated with LPS + IFNγ, indicating that inhibition of cPLA2 activation results in increased membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity in cells. These results suggest that activated cPLA2 helps attenuate the increase in the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity to maintain endocytosis of oAβ in stimulated microglia.

Fig. 7.

Membrane tethering force of BV2 cells. (a) A typical AFM force curve from the cell. Red line is the approaching curve and blue line is the retraction curve. Magnified the retraction curve at point F shows a sudden release of force as a membrane tethering force where a membrane tethering rupture event happened. The membrane tethering force measured from this event is around 50 pN. (b) Membrane tethering force in BV2 cells. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 μM MAFP for 30 min, followed by 1 μg/ml LPS + 10 ng/ml IFNγ treatment for 1 h. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM from 45-128 membrane tethering events (n= 45 - 128). *** P < 0.001 compared with the control group; #P < 0.05 compared with the LPS + IFNγ group.

Discussion

Microglia have been found to be immunoreactive for cPLA2 in central nervous system (CNS) injury and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease [2]. Upregulation of cPLA2 in microglia can be induced through the redox-sensitive NF-κB activation, and in turn, cPLA2 plays a major role in Aβ-induced NADPH oxidase activity, superoxide production, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) formation, iNOS expression, and NO production in microglia [39], However, AD-related cPLA2 function has yet to be fully elucidated. Our data clearly show that cPLA2 plays a role in oAβ association with microglia through regulation of the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity.

The soluble, monomeric, and oligomeric forms of Aβ aggregate to produce fibrillar Aβ (fAβ). However, microglia do not effectively clear fAβ [40,41], and oAβ has been found to be the most neurotoxic among other forms of Aβ [24]. Therefore, understanding the mechanism(s) involving in the maintenance of oAβ homeostasis provides important information regarding the development of AD pathology. Although receptor-mediated phagocytosis of fAβ has been studied extensively, the mechanism(s) underlying oAβ association with microglia are largely unknown. It has been reported that microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Aβ through fluid phase macropinocytosis [42]. The uptake of oAβ is dependent on both actin and tubulin dynamics, but does not involve clathrin assembly, coated vesicles or membrane cholesterol, and the uptake of soluble Aβ and fAβ occurs largely through distinct mechanisms and upon accumulation are segregated into separate subcellular vesicular compartments [42,43]. These previous findings suggest that oAβ uptake by microglia is intimately related to the composition and physical properties of the plasma membrane, and the interaction between the plasma membrane and cytoskeleton beneath the plasma membrane. Since cPLA2 is a lipid-modifying enzyme, and increased activities have been found in AD brains, it is important to investigate the role of cPLA2 in oAβ association with microglia.

Lipid-modifying enzymes induce membrane curvature for biogenesis of transport carriers [44,45]. As activated cPLA2 targets cellular membranes to hydrolyze phospholipids to produce fatty acids and lysophospholipids, it has been hypothesized that converting cylinder-shaped phospholipids into wedge-like lysophospholids by activated cPLA2 alters lipid geometry favorable for the generation of positive membrane curvature, and supports the budding of tubular transport [46,47]. In turn, cPLA2 was found to be a key driver for recycling through the clathrin-independent endocytic route [48]. These previous findings suggest that activated cPLA2 facilitates clathrin-independent fluid phase macropinocytosis of oAβ in microglia.

In addition to membrane bending or curvature, the mechanochemical process of endocytosis, including receptor-mediated and fluid phase endocytosis, is controlled not only biochemically through interaction with regulatory proteins, but also physically through an apparently continuous adhesion (or connectivity) between plasma membrane lipids and cytoskeletal proteins [23]. Membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion is the key mechanical resistance for the formation of endocytic vesicles, and has been found to be the major factor in the force for membrane tether formation (Fmtf) [33]. Therefore, Fmtf can be a measure for the membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity. Modifying the plasma membrane by exposing cells to amphiphilic compounds including detergents, lipids, and solvents, has been demonstrated to cause a parallel decrease in Fmtf and rise in endocytosis rate [35,49]. Here we employed atomic force microscopy (AFM) to measure Fmtf for studying the mechanical mechanism underlying the effects of cPLA2, a lipid-modifying enzyme, on oAβ association with microglia. Fmtf of (LPS+IFNγ)-stimulated cells was higher than that of control cells (Fig. 7b). This result is consistent with the notion that the inflammatory environment in the AD brain may increase membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity to lower the ability of microglia to macropinocytose oAβ from the milieu, acting to promote disease pathogenesis. In fact, anti-inflammatory agents have been reported to enhance the ability of microglia to process Aβ [50-53], and prevent neuroinflammation, lower Aβ levels and improve cognitive performance in Tg APP mice [54]. Interestingly, inhibition of cPLA2 by MAFP further increased Fmtf both unstimulated and stimulated cells (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that stimulated cells have higher membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity, and cPLA2 activation attenuated the increase in membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity to help maintain the endocytosis rate.

Although cPLA2 did not play a role in the degradation of associated Aβ (Fig. 5b), our data clearly show that ~ 65% of associated Aβ was rapidly digested through lysosomal activities (Fig. 5a). ~35% of associated Aβ remained in the cells and suggested that there was no significant Aβ recycling back to culture medium (Fig. 5a). These results are consistent with previous findings that soluble Aβ is rapidly trafficked into late endolysosomal compartments and subject to degradation without significant Aβ recycling back to culture medium [42]. Once accumulated, Aβ microaggregates colocalize to cellular fractions containing the lysosomal markers β-hexosaminidase and acid phosphatase [55].

cPLA2 has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases and brain injury including AD and cerebral ischemia [56-58,3]. Therefore, examining the effects of cPLA2 activities in brains using animal models have been a research focus. For example, genetic ablation or reduction of cPLA2 protected human amyloid precursor protein (hAPP) mice against Aβ-dependent deficits in learning and memory, behavioral alterations and premature mortality [59]. Lithium activated brain phospholipase A2 and improves memory in rats [60]. In vivo inhibition of cPLA2 in rat brain decreased the levels of total Tau protein [61]. Another line of research on cPLA2 is to address its functional roles in AD pathology. Modulations of cPLA2 activation by Aβ stimulation and inhibitors altered membrane fluidity and molecular order [62,19,63]. Therefore, Aβ-activated cPLA2 may also alter functions of organelles through its ability to alter cellular membrane properties. For example, cPLA2 has been found to mediate Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in astrocytes [64]. Consistently, inhibition of cPLA2 diminished Aβ-induced neurotoxicity [59]. Both NMDA and oAβ activated cPLA2 leading to release of arachidonic acid (AA) in primary rat neurons [20]. In turn, AA served not only as a precursor for eicosanoids, but also as a retrograde messenger which plays a role in modulating synaptic plasticity [20]. Aβ also induced elevation of APP protein expression mediated by cPLA2, PGE2 release, and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) activation via protein kinase A pathway in primary rat cortical neuronal cultures [65]. In this study, our results contribute to the functional roles of cPLA2 in AD pathology by demonstrating its role in facilitating oAβ association with microglia through its regulation of membrane-cytoskeleton connectivity. Better understanding the functional roles of cPLA2 in AD pathology should provide critical insights into the development of therapeutic strategies for AD treatment.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging, Grant 5 R01 AG044404 (to J.C.L)

References

- 1.Lee CY, Landreth GE (2010) The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 117 (8):949–960. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0433-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephenson D, Rash K, Smalstig B, Roberts E, Johnstone E, Sharp J, Panetta J, Little S, Kramer R, Clemens J (1999) Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is induced in reactive glia following different forms of neurodegeneration. Glia 27 (2):110–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephenson DT, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Clemens JA (1996) Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) immunoreactivity is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol Dis 3 (1):51–63. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW (1995) Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 20 (3):269–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuroff L, Daley D, Black KL, Koronyo-Hamaoui M (2017) Clearance of cerebral Abeta in Alzheimer’s disease: reassessing the role of microglia and monocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenkel D, Wilkinson K, Zhao L, Hickman SE, Means TK, Puckett L, Farfara D, Kingery ND, Weiner HL, El Khoury J (2013) Scara1 deficiency impairs clearance of soluble amyloid-beta by mononuclear phagocytes and accelerates Alzheimer’s-like disease progression. Nat Commun 4:2030. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang CN, Shiao YJ, Shie FS, Guo BS, Chen PH, Cho CY, Chen YJ, Huang FL, Tsay HJ (2011) Mechanism mediating oligomeric Abeta clearance by naive primary microglia. Neurobiol Dis 42 (3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenigsknecht J, Landreth G (2004) Microglial phagocytosis of fibrillar beta-amyloid through a beta1 integrin-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 24 (44):9838–9846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson K, El Khoury J (2012) Microglial scavenger receptors and their roles in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012:489456. doi: 10.1155/2012/489456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Y, Ye RD (2015) Microglial Abeta receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 35 (1):71–83. doi: 10.1007/s10571-014-0101-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, Hazrati L, Collinge J, Pocock J, Lashley T, Williams J, Lambert JC, Amouyel P, Goate A, Rademakers R, Morgan K, Powell J, St George-Hyslop P, Singleton A, Hardy J, Alzheimer Genetic Analysis G (2013) TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 368 (2):117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, Rujescu D, Hampel H, Giegling I, Andreassen OA, Engedal K, Ulstein I, Djurovic S, Ibrahim-Verbaas C, Hofman A, Ikram MA, van Duijn CM, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K (2013) Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 368 (2):107–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulland TK, Song WM, Huang SC, Ulrich JD, Sergushichev A, Beatty WL, Loboda AA, Zhou Y, Cairns NJ, Kambal A, Loginicheva E, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Virgin HW, Unanue ER, Wang Y, Artyomov MN, Holtzman DM, Colonna M (2017) TREM2 Maintains Microglial Metabolic Fitness in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 170 (4):649–663.e613. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh FL, Wang Y, Tom I, Gonzalez LC, Sheng M (2016) TREM2 Binds to Apolipoproteins, Including APOE and CLU/APOJ, and Thereby Facilitates Uptake of Amyloid-Beta by Microglia. Neuron 91 (2):328–340. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed-Geaghan EG, Savage JC, Hise AG, Landreth GE (2009) CD14 and toll-like receptors 2 and 4 are required for fibrillar A{beta}-stimulated microglial activation. J Neurosci 29 (38):11982–11992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3158-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udan ML, Ajit D, Crouse NR, Nichols MR (2008) Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 mediate Abeta(1–42) activation of the innate immune response in a human monocytic cell line. J Neurochem 104 (2):524–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollingworth P, Harold D, Sims R, Gerrish A, Lambert JC, Carrasquillo MM, Abraham R, Hamshere ML, Pahwa JS, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Jones N, Stretton A, Thomas C, Richards A, Ivanov D, Widdowson C, Chapman J, Lovestone S, Powell J, Proitsi P, Lupton MK, Brayne C, Rubinsztein DC, Gill M, Lawlor B, Lynch A, Brown KS, Passmore PA, Craig D, McGuinness B, Todd S, Holmes C, Mann D, Smith AD, Beaumont H, Warden D, Wilcock G, Love S, Kehoe PG, Hooper NM, Vardy ER, Hardy J, Mead S, Fox NC, Rossor M, Collinge J, Maier W, Jessen F, Ruther E, Schurmann B, Heun R, Kolsch H, van den Bussche H, Heuser I, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Dichgans M, Frolich L, Hampel H, Gallacher J, Hull M, Rujescu D, Giegling I, Goate AM, Kauwe JS, Cruchaga C, Nowotny P, Morris JC, Mayo K, Sleegers K, Bettens K, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP, Van Broeckhoven C, Livingston G, Bass NJ, Gurling H, McQuillin A, Gwilliam R, Deloukas P, Al-Chalabi A, Shaw CE, Tsolaki M, Singleton AB, Guerreiro R, Muhleisen TW, Nothen MM, Moebus S, Jockel KH, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, Pankratz VS, Sando SB, Aasly JO, Barcikowska M, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM, Ikram MA, DeStefano AL, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Launer LJ, Seshadri S, consortium C, Berr C, Campion D, Epelbaum J, Dartigues JF, Tzourio C, Alperovitch A, Lathrop M, consortium E, Feulner TM, Friedrich P, Riehle C, Krawczak M, Schreiber S, Mayhaus M, Nicolhaus S, Wagenpfeil S, Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Jonsson PV, Chouraki V, Genier-Boley B, Hiltunen M, Soininen H, Combarros O, Zelenika D, Delepine M, Bullido MJ, Pasquier F, Mateo I, Frank-Garcia A, Porcellini E, Hanon O, Coto E, Alvarez V, Bosco P, Siciliano G, Mancuso M, Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Nacmias B, Sorbi S, Bossu P, Piccardi P, Arosio B, Annoni G, Seripa D, Pilotto A, Scarpini E, Galimberti D, Brice A, Hannequin D, Licastro F, Jones L, Holmans PA, Jonsson T, Riemenschneider M, Morgan K, Younkin SG, Owen MJ, O’Donovan M, Amouyel P, Williams J (2011) Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 43 (5):429–435. doi: 10.1038/ng.803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, Gallins PJ, Buxbaum JD, Jarvik GP, Crane PK, Larson EB, Bird TD, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, De Jager PL, Evans D, Schneider JA, Carrasquillo MM, Ertekin-Taner N, Younkin SG, Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Nowotny P, Kramer P, Hardy J, Huentelman MJ, Myers AJ, Barmada MM, Demirci FY, Baldwin CT, Green RC, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop P, Arnold SE, Barber R, Beach T, Bigio EH, Bowen JD, Boxer A, Burke JR, Cairns NJ, Carlson CS, Carney RM, Carroll SL, Chui HC, Clark DG, Corneveaux J, Cotman CW, Cummings JL, DeCarli C, DeKosky ST, Diaz-Arrastia R, Dick M, Dickson DW, Ellis WG, Faber KM, Fallon KB, Farlow MR, Ferris S, Frosch MP, Galasko DR, Ganguli M, Gearing M, Geschwind DH, Ghetti B, Gilbert JR, Gilman S, Giordani B, Glass JD, Growdon JH, Hamilton RL, Harrell LE, Head E, Honig LS, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Jicha GA, Jin LW, Johnson N, Karlawish J, Karydas A, Kaye JA, Kim R, Koo EH, Kowall NW, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Lieberman AP, Lopez OL, Mack WJ, Marson DC, Martiniuk F, Mash DC, Masliah E, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, McDavid AN, McKee AC, Mesulam M, Miller BL, Miller CA, Miller JW, Parisi JE, Perl DP, Peskind E, Petersen RC, Poon WW, Quinn JF, Rajbhandary RA, Raskind M, Reisberg B, Ringman JM, Roberson ED, Rosenberg RN, Sano M, Schneider LS, Seeley W, Shelanski ML, Slifer MA, Smith CD, Sonnen JA, Spina S, Stern RA, Tanzi RE, Trojanowski JQ, Troncoso JC, Van Deerlin VM, Vinters HV, Vonsattel JP, Weintraub S, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Williamson J, Woltjer RL, Cantwell LB, Dombroski BA, Beekly D, Lunetta KL, Martin ER, Kamboh MI, Saykin AJ, Reiman EM, Bennett DA, Morris JC, Montine TJ, Goate AM, Blacker D, Tsuang DW, Hakonarson H, Kukull WA, Foroud TM, Haines JL, Mayeux R, Pericak-Vance MA, Farrer LA, Schellenberg GD (2011) Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 43 (5):436–441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hicks JB, Lai Y, Sheng W, Yang X, Zhu D, Sun GY, Lee JC (2008) Amyloid-beta peptide induces temporal membrane biphasic changes in astrocytes through cytosolic phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta 1778 (11):2512–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelat PB, Chalimoniuk M, Wang JH, Strosznajder JB, Lee JC, Sun AY, Simonyi A, Sun GY (2008) Amyloid beta peptide and NMDA induce ROS from NADPH oxidase and AA release from cytosolic phospholipase A2 in cortical neurons. J Neurochem 106 (1):45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu DX, Zhao WD, Fang WG, Chen YH (2012) cPLA2alpha-mediated actin rearrangements downstream of the Akt signaling is required for Cronobacter sakazakii invasion into brain endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 417 (3):925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moes M, Boonstra J, Regan-Klapisz E (2010) Novel role of cPLA(2)alpha in membrane and actin dynamics. Cell Mol Life Sci 67 (9):1547–1557. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0267-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheetz MP (2001) Cell control by membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 (5):392–396. doi: 10.1038/35073095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB Jr., Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ(2002) Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem 277 (35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ni M, Aschner M (2010) Neonatal rat primary microglia: isolation, culturing, and selected applications. Curr Protoc Toxicol Chapter 12:Unit 12 17. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1217s43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuang DY, Simonyi A, Kotzbauer PT, Gu Z, Sun GY (2015) Cytosolic phospholipase A2 plays a crucial role in ROS/NO signaling during microglial activation through the lipoxygenase pathway. J Neuroinflammation 12:199. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0419-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stine WB, Jungbauer L, Yu C, LaDu MJ (2011) Preparing synthetic Abeta in different aggregation states. Methods Mol Biol 670:13–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-744-0_2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giulian D, Baker TJ (1986) Characterization of ameboid microglia isolated from developing mammalian brain. J Neurosci 6 (8):2163–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stansley B, Post J, Hensley K (2012) A comparative review of cell culture systems for the study of microglial biology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 9:115. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Majumdar A, Cruz D, Asamoah N, Buxbaum A, Sohar I, Lobel P, Maxfield FR (2007) Activation of microglia acidifies lysosomes and leads to degradation of Alzheimer amyloid fibrils. Mol Biol Cell 18 (4):1490–1496. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golde TE, Estus S, Younkin LH, Selkoe DJ, Younkin SG (1992) Processing of the amyloid protein precursor to potentially amyloidogenic derivatives. Science 255 (5045):728–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seglen PO (1983) Inhibitors of lysosomal function. Methods Enzymol 96:737–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai J, Sheetz MP (1999) Membrane tether formation from blebbing cells. Biophys J 77 (6):3363–3370. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77168-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT (2008) Mediation, modulation, and consequences of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions. Annu Rev Biophys 37:65–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai J, Sheetz MP, Wan X, Morris CE (1998) Membrane tension in swelling and shrinking molluscan neurons. J Neurosci 18 (17):6681–6692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raucher D (2008) Chapter 17: Application of laser tweezers to studies of membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. In: Methods Cell Biol, vol 89 pp 451–466. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00617-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun M, Graham JS, Hegedus B, Marga F, Zhang Y, Forgacs G, Grandbois M (2005) Multiple membrane tethers probed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J 89 (6):4320–4329. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun M, Northup N, Marga F, Huber T, Byfield FJ, Levitan I, Forgacs G (2007) The effect of cellular cholesterol on membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion. J Cell Sci 120 (Pt 13):2223–2231. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szaingurten-Solodkin I, Hadad N, Levy R (2009) Regulatory role of cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha in NADPH oxidase activity and in inducible nitric oxide synthase induction by aggregated Abeta1–42 in microglia. Glia 57 (16):1727–1740. doi: 10.1002/glia.20886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolmont T, Haiss F, Eicke D, Radde R, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Kohsaka S, Jucker M, Calhoun ME (2008) Dynamics of the microglial/amyloid interaction indicate a role in plaque maintenance. J Neurosci 28 (16):4283–4292. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4814-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers J, Lue LF (2001) Microglial chemotaxis, activation, and phagocytosis of amyloid beta-peptide as linked phenomena in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 39 (5–6):333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CY, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE (2009) Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci 29 (13):4252–4262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wesen E, Jeffries GDM, Matson Dzebo M, Esbjorner EK (2017) Endocytic uptake of monomeric amyloid-beta peptides is clathrin-and dynamin-independent and results in selective accumulation of Abeta(l-42) compared to Abeta(l-40). Sci Rep 7 (1):2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02227-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graham TR, Kozlov MM (2010) Interplay of proteins and lipids in generating membrane curvature. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22 (4):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprong H, van der Sluijs P, van Meer G (2001) How proteins move lipids and lipids move proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2 (7):504–513. doi: 10.1038/35080071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bechler ME, de Figueiredo P, Brown WJ (2012) A PLA1–2 punch regulates the Golgi complex. Trends Cell Biol 22 (2):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ha KD, Clarke BA, Brown WJ (2012) Regulation of the Golgi complex by phospholipid remodeling enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821 (8):1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capestrano M, Mariggio S, Perinetti G, Egorova AV, lacobacci S, Santoro M, Di Pentima A, lurisci C, Egorov MV, Di Tullio G, Buccione R, Luini A, Polishchuk RS (2014) Cytosolic phospholipase A2ε drives recycling through the clathrin-independent endocytic route. Journal of Cell Science 127 (5):977–993. doi: 10.1242/jcs,136598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raucher D, Sheetz MP (1999) Membrane expansion increases endocytosis rate during mitosis. J Cell Biol 144 (3):497–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Shimy IA, Heikal OA, Hamdi N (2015) Minocycline attenuates Abeta oligomers-induced pro-inflammatory phenotype in primary microglia while enhancing Abeta fibrils phagocytosis. Neurosci Lett 609:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varnum MM, Kiyota T, Ingraham KL, Ikezu S, Ikezu T (2015) The anti-inflammatory glycoprotein, CD200, restores neurogenesis and enhances amyloid phagocytosis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 36 (ll):2995–3007. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Medeiros R, Kitazawa M, Passos GF, Baglietto-Vargas D, Cheng D, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM (2013) Aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 stimulates alternative activation of microglia and reduces Alzheimer disease-like pathology in mice. Am J Pathol 182 (5):1780–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimizu E, Kawahara K, Kajizono M, Sawada M, Nakayama H (2008) IL-4-induced selective clearance of oligomeric beta-amyloid peptide(l-42) by rat primary type 2 microglia. J Immunol 181 (9):6503–6513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin-Moreno AM, Brera B, Spuch C, Carro E, Garcia-Garcia L, Delgado Μ, Pozo MA, Innamorato NG, Cuadrado A, de Ceballos ML (2012) Prolonged oral cannabinoid administration prevents neuroinflammation, lowers beta-amyloid levels and improves cognitive performance in Tg APP 2576 mice. J Neuroinflammation 9:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knauer MF, Soreghan B, Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Glabe CG (1992) Intracellular accumulation and resistance to degradation of the Alzheimer amyloid A4/beta protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89 (16):7437–7441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun GY, Xu J, Jensen MD, Simonyi A (2004) Phospholipase A2 in the central nervous system: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Lipid Res 45 (2):205–213. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300016-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun GY, He Y, Chuang DY, Lee JC, Gu Z, Simonyi A, Sun AY (2012) Integrating cytosolic phospholipase A(2) with oxidative/nitrosative signaling pathways in neurons: a novel therapeutic strategy for AD. Mol Neurobiol 46 (l):85–95. doi: 10.1007/sl2035-012-8261-l [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG (2000) Neuroinflammatory signaling upregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res 25 (9–10):1173–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanchez-Mejia RO, Newman JW, Toh S, Yu GQ, Zhou Y, Halabisky B, Cisse M, Scearce-Levie K, Cheng IH, Gan L, Palop JJ, Bonventre JV, Mucke L (2008) Phospholipase A2 reduction ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 11 (11):1311–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn.2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mury FB, da Silva WC, Barbosa NR, Mendes CT, Bonini JS, Sarkis JE, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Gattaz WF, Dias-Neto E (2016) Lithium activates brain phospholipase A2 and improves memory in rats: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 266 (7):607–618. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0665-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaeffer EL, De-Paula VJ, da Silva ER, de ANB, Skaf HD, Forlenza OV, Gattaz WF (2011) Inhibition of phospholipase A2 in rat brain decreases the levels of total Tau protein. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 118 (9):1273–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0619-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schaeffer EL, Skaf HD, Novaes Bde A, da Silva ER, Martins BA, Joaquim HD, Gattaz WF (2011) Inhibition of phospholipase A(2) in rat brain modifies different membrane fluidity parameters in opposite ways. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35 (7):1612–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu D, Hu C, Sheng W, Tan KS, Haidekker MA, Sun AY, Sun GY, Lee JC (2009) NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species production alters astrocyte membrane molecular order via phospholipase A2. Biochem J 421 (2):201–210. doi: 10.1042/bj20090356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu D, Lai Y, Shelat PB, Hu C, Sun GY, Lee JC (2006) Phospholipases A2 mediate amyloid-beta peptide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci 26 (43):11111–11119. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3505-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sagy-Bross C, Kasianov K, Solomonov Y, Braiman A, Friedman A, Hadad N, Levy R (2015) The role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha in amyloid precursor protein induction by amyloid beta1–42 : implication for neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 132 (5):559–571. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]